Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to expand upon the literature examining the relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms among different ethnic groups. Specifically, acculturative stress was explored as a moderator of the relationship between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms among ethnic minority women. Additionally, the distinction between acculturative stress and general life stress in predicting eating disorder symptoms was assessed. Participants consisted of 247 undergraduate women, all of whom were members of an ethnic minority group including African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinas. Acculturative stress was found to moderate the relationship between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms, but only among African American women. Acculturative stress was also found to significantly predict bulimic symptoms above and beyond general life stress among African American, Asian American, and Latina women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Historically, eating disorders were considered “culture bound syndromes” occurring in Western societies among White women from higher socio-economic status (Bruch, 1973). However, extensive research indicates that eating disorders also occur in ethnic minority women in the United States (Alegria et al., 2007; Nicdao et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). For example, comparable rates of eating disorder symptoms such as vomiting, and use of laxatives, diuretics, and diet pills are reported among Latinas and Caucasians (Cachelin et al., 2000; Crago & Shisslak, 2003; Fisher et al., 1994; le Grange et al., 1997; Pumariega, 1986; Regan & Cachelin, 2006). African Americans tend to report less body dissatisfaction, dieting, and dietary restraint than Caucasians (Grabe & Hyde, 2006; O’Neill, 2003; Striegel-Moore et al., 2003), but report equal rates of binge eating and bulimic symptoms (Bardone-Cone & Boyd, 2007; Pike et al., 2001; White & Grilo, 2005). Among Asian Americans the literature is inconclusive, with some researchers finding similar levels of eating disorder symptoms when compared to Caucasians (Franko et al., 2007), while others have found lower levels (Regan & Cachelin, 2006; Tsai & Gray, 2000). Since ethnic minority women are at risk for developing eating disorder symptoms, which are associated with a number of negative physical health and psychological consequences (Moradi & Subich, 2002; Thompson & Stice, 2001; Tylka & Hill, 2004), exploring factors that can influence the development of eating disorder symptoms among ethnic minority women is important.

The role of culture in the development of eating disorder symptoms

Body dissatisfaction, known as the discrepancy between the perceived self and the ideal self, is consistently identified as a risk factor for the development of eating disorder symptoms (Cash & Deagle, 1997; Fairburn et al., 1993, 2003; Hrabosky & Grilo, 2007; Polivy & Herman, 2002). The development of body dissatisfaction is heavily influenced by society’s portrayal of beauty (Silberstein et al., 1988), and is posited to result primarily from sociocultural pressures to be thin and an inability to achieve the ideal of beauty currently revered in a particular culture (Striegel-Moore et al., 1986; Wertheim et al., 1997). Every culture has its own view of what constitutes attractiveness in physical appearance, thus body types commonly associated with body dissatisfaction differ across cultures (Hodes et al., 1996; Joiner & Kashubeck, 1996; Lawrence & Thelen, 1995; Lopez et al. 1995). Culturally accepted ideal beauty prototypes may become incorporated into a person’s ideal self and subsequently shape personal evaluations and associated affective experiences related to the body. Since the White, ultra-thin, ideal body image portrayed by the media in Western society is unattainable for most individuals (Cusumano & Thompson, 1997; Stice & Shaw, 1994), attempts to attain this body type often result in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating (Agliata & Tantleff-Dunn, 2004; Moradi & Subich, 2002). These symptoms of disordered eating then place individuals at greater risk of experiencing physical health problems, such as loss of teeth enamel, infertility, stress fractures, malnutrition, and cardiac arrest (Mitchell & Crow, 2006) and increased risk of future obesity (Wilson et al., 2003), and mortality (Thompson & Stice, 2001).

For non-White, ethnic minority women who migrate to the United States from another country or are born within an ethnic group that does not subscribe to the White thin-ideal prototype proposed in Western society, the degree of acculturation may account for their body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms. Acculturation is the process by which an individual adopts the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of the dominant culture (Berry, 1998). Specifically, people often evaluate and change their physical appearance in the process of acculturation in order to conform to cultural standards of beauty (Bem, 1981). This new cultural ideal is internalized and becomes the standard to which an individual compares their perceived self (Guinn et al., 1997; Lopez et al., 1995). Acculturation to Western society in particular may increase the risk of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating for some individuals because the current ideal body image purported by Western society is White, and much thinner and unattainable than the ideal body image from other cultures and societies (Cusumano & Thompson, 1997; Stice & Shaw, 1994).

The process of acculturation is often accompanied by acculturative stress, known as the stress of moving one from culture to another culture (Berry, 1998). Acculturative stress includes the balance of participating in activities, values, beliefs, and practices of the dominant culture versus the culture of origin (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996), and is associated with a host of mental health symptoms such as general psychological distress (Neff & Hoppe, 1993), depression and suicide (Joiner & Walker, 2002), substance use (Ortega et al., 2000), and eating disorder symptoms (Perez et al., 2002). In addition to mental health consequences, acculturative stress is associated with negative physical health problems, such as poorer overall health and increased risk of mortality (Bauer et al., 2012; Finch & Vega, 2003; Kirmayer & Sartorius, 2007). Acculturative stress also creates unique stressors that are distinct from general life stress, such as discrimination and increased family conflict when adapting to the dominant culture (Anderson, 1991). This distinction between acculturative and general life stress is supported by results from one study which indicate that acculturative stress predicts depressive and anxious symptoms above and beyond general life stress in a sample of African Americans (Joiner & Walker, 2002). However, no further work has been done to discriminate acculturative stress from general life stress in relation to eating disorder symptoms.

Acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms

Research on the relationship between acculturation and eating disorder symptoms collectively indicates that ethnic minority women who acculturate to Western society are at an increased risk for experiencing body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms. For example, ethnic minority women who move from a non-Westernized country to the United States are at greater risk for developing eating disorders than women who remained in their homelands (Dolan, 1991; Furukawa, 1994; Silber, 1986). Other studies indicate that Latina women who are more acculturated are more likely to endorse greater levels of body dissatisfaction (Lopez et al., 1995) and eating disorder symptoms (Chamorro & Flores-Ortiz, 2000; Pumariega, 1986) than less acculturated Latina women. Similarly, the degree to which African American women internalize the values and identify with American culture is associated with higher levels of body dissatisfaction (Lester & Petrie, 1998). Additionally, the more acculturated African American women perceive themselves to be, the higher their reported level of eating disorder symptoms (Abrams et al., 1993). This relationship also generalizes to Chinese American women, with one study indicating that higher levels of acculturation were associated with more symptoms of disordered eating among Chinese American women (Davis & Katzman, 1999).

While a number of studies have explored the impact of acculturation on ethnic minority women, fewer studies have explored the role of acculturative stress specifically in relation to eating disorder symptoms. One study conducted by Perez et al. (2002) found acculturative stress to be a moderator of body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms among a group of ethnic minority women comprised of African American and Latinas. This study also indicates that African American and Latina women who endorse high levels of acculturative stress and body dissatisfaction also endorse bulimic symptoms, and minority women who do not endorse high levels of acculturative stress do not endorse bulimic symptoms even if they are dissatisfied with their bodies (Perez et al., 2002). Another study among African American and Latina women found that acculturative stress predicts bulimic symptoms among African American women, and drive for thinness among Latina women, while acculturation did not predict eating disorder symptoms (Gordon et al., 2010). Likewise, increased levels of cultural conflict (i.e., acculturative stress) are also associated with body dissatisfaction and eating disorder attitudes among Asian women, while acculturation is not (Reddy & Crowther, 2007). A recent study among Hispanic males also found that acculturative stress and not acculturation significantly predicted internalization of Western ideals for body image and body dissatisfaction (Warren & Rios, 2012). While the results from these studies provide evidence that supports the relationship between levels of acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms, only a small number of studies exist. Therefore, further research is needed before definitive conclusions can be made.

It is especially important to explore the relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms in college women, as ethnic minority college women are at greater risk for experiencing both high levels of acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms. Specifically, a number of studies indicate that ethnic minority college students are more likely to experience difficulty with acculturative stress issues (Constantine et al., 2004; Crockett et al., 2007; Joiner & Walker, 2002; Paukert et al., 2006; Walker et al., 2008), as college is a time associated with conflicting value systems (Crockett et al., 2007). In addition, prevalence rates of eating disorder symptoms among college women are significantly higher than other samples (Fairburn & Beglin, 1990; Mintz & Betz, 1988), regardless of ethnicity. In fact, one study indicates that women with no history of disordered eating symptoms before their freshman year of college are significantly more likely to report these behaviors during their first year in college (Striegel-Moore et al., 1986).

The current study

Given the paucity of research on the relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms; the current study sought to expand upon the literature by exploring the relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms among African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinas. Specifically, the current study will attempt to replicate upon the Perez et al. (2002) study by exploring acculturative stress as a moderator of the relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among ethnic minority women. However, the current study expands upon the previous study by Perez et al. by including Asian women, and exploring the ethnic minority groups separately, as the previous study included only African American and Latina women, and combined all ethnic minority women into one group. Based on the results from the Perez et al. (2002) study, it was hypothesized that acculturative stress would moderate the relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among African Americans, Latinas, and Asians. It is theoretically plausible that acculturative stress moderates the relationship between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms, as ethnic minority women who report experiencing body dissatisfaction but have little to no acculturative stress may not have sufficient motivation to engage in bulimic symptoms in an attempt to obtain the White, thin-ideal body type proposed by Western society. To expand upon previous research, associations among drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and bulimic symptoms and acculturative and general life stress among the different ethnic groups will also be examined.

The second objective of this study was to assess if acculturative stress was related to eating disorder symptoms above and beyond general life stress. Anyone undergoing a challenging negative life event may experience interpersonal conflicts at work, school, or with friends and families, which constitute general life stress. Anderson (1991) argued that acculturative stress for ethnic minority groups goes beyond general life stress and relates to specific events and stressors related to adapting to a dominant culture, such as perceived discrimination or negative reactions from friends and families for adapting to the dominant culture. Most of the research investigating acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms has been conducted on college samples (Perez et al., 2002; Gordon et al., 2010; Warren & Rios, 2012), and college is a time period associated with identity development and conflicting value systems (Crockett et al., 2007). Thus, it is important to distinguish if the relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms is unique and separate from general life stress. There has been one study that investigated the validity of acculturative stress and found that among African Americans, acculturative stress predicts depression and anxiety symptoms above and beyond general life stress (Joiner & Walker, 2002). Therefore, it was hypothesized that acculturative stress would predict eating disorder symptoms with unique variance separate from general life stress.

Method

Participants and procedures

Participants consisted of 247 undergraduate college women from a large public university in the southern US Participants ranged in age from 17 to 25 (M = 19.00, SD = 1.71), with 90 (37 %) participants identifying as Latina, 85 (34 %) as African American, and 72 (29 %) as Asian American. There were 49 (20 %) women born outside of the US, 165 (67 %) born within the US, and 33 (13 %) did not indicate country of origin or generational status. For those women born outside of the US, three reported living in the US for 1–4 years, five reported living in the US for 5–8 years, seven reported living in the US for 11–15 years, and ten reported living in the US for 16–23 years. In terms of generational status, 16 (14 %) participants reported being first generation, six (5 %) reported being second generation, five (4 %) reported being third generation, seven (6 %) reported being fourth generation, 18 (16 %) reported being fifth or greater generation, and the remainder of participants (n = 57, 49 %) did not report generational status.

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board, participants were recruited from undergraduate psychology courses. Participants were informed that they would be completing questionnaires about their emotions, self-concept, and stress. Participants provided written consent before beginning the study and were debriefed upon completion of the questionnaires. All questionnaires were administered in English, and administration was conducted in groups of approximately 20. Participants either volunteered for the study or participated to fulfill a requirement for their undergraduate psychology course.

Measures

Acculturative stress

The short version of the Societal, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environmental Acculturative Stress Scale (SAFE; Padilla et al., 1985) was used to assess levels of acculturative stress. The short version of the SAFE is a modified version of the original 60-item SAFE scale and contains items measuring acculturative stress in social, attitudinal, familial, and environmental contexts, along with perceived discrimination toward immigrant populations (Mena et al., 1987). Participants rate each item that applied to them on a scale ranging from 1 (not stressful) to 5 (extremely stressful), and rate each item that did not apply to them as a 0 (not applicable). The possible scores for the SAFE ranged from 0 to 120. Predictive validity for the SAFE has been demonstrated for depression, and anxiety among African American women (Joiner & Walker, 2002) and Latinas (Kiang et al., 2010), and negative affect among Asian Americans (Paukert et al., 2006). The SAFE has also demonstrated discriminant validity from general life stress among African Americans and Latinas (Joiner & Walker, 2002; Kiang et al., 2010). This scale has also shown reliability for Asian Americans and international students (α = .89; Mena et al., 1987), for a heterogeneous group of Latinas (α = .89; Fuertes & Westbrook, 1996), and for a heterogeneous group of African American students (α = .87; Perez et al., 2002). In this sample, alpha coefficients for the SAFE were .91 for Asian Americans, .87 for African Americans, and .91 for Latinas.

Eating disorder symptoms

The Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI; Garner et al., 1983) was used to assess symptoms of eating disorders and body dissatisfaction. The EDI consists of 64-items rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always) that comprise eight subscales. Three of the subscales measure clinical eating disorder symptoms while five of the other subscales measure correlates of eating disorders. The current study focuses on three clinical subscales: the Drive for Thinness subscale (DT) which measures fear of weight gain and dieting behaviors; the Bulimia subscale (B) which measures binge eating and emotional eating behaviors; and the Body Dissatisfaction subscale (BD) which measures satisfaction with particular body parts and overall shape and was used to assess body dissatisfaction for the current study. Research on the EDI and its subscales has demonstrated adequate internal consistency coefficients (Garner et al., 1983), including populations of African Americans (Perez et al., 2002), Latinas (Gordon et al., 2010), and Asian Americans (Sabik et al., 2010). Construct validity for the EDI subscales has also been demonstrated when compared to other eating disorder measures in populations of African American women (Kelly et al., 2012). Predictive validity for the EDI subscales in predicting perceived ideal body shape has been demonstrated among African American and Latina women (Gordon et al., 2010). For the current study, alpha coefficients for the Asian American group were .91 for DT, .83 for B, and .90 for BD. Alpha coefficients for the African American group were .89 for DT, .81 for B, and .89 for BD. Alpha coefficients for the Latina group were .89 for DT, .84 for B, and .90 for BD.

General life stress

The Negative Life Events Questionnaire (NLEQ; Saxe & Abramson, 1987) was used to assess general life stress related to negative life events. The NLEQ was developed specifically for use with college students and includes several categories of negative life events to ensure broad coverage. Specifically, the measure contains 66 items that assess negative life stressors in the domains of school, work, family, friends, and others. Participants are asked to rank items by how frequently they had occurred during the past 4 weeks on a scale ranging from 0 (never present) to 4 (always present). Total scale scores are calculated by summing all items with higher scores indicating higher general levels of stress related to negative life events. Previous research on the NLEQ has demonstrated adequate predictive and concurrent validity among college students due to the finding that scores on the NLEQ have been associated with current and future depressive symptoms and negative affect (Alloy & Clements, 1992; Metalsky & Joiner, 1992). While research on the NLEQ has not explored ethnic differences on this measure, the questionnaire contains items regarding negative life events that would be similar for college students regardless of ethnicity. The NLEQ has also demonstrated test re-test reliability (r = .82; Saxe & Abramson, 1987). Calculations of internal consistency coefficients are not appropriate for this scale due to varied item responses based on the type and frequency of life stress experienced (Bernert et al., 2007).

Results

Descriptive statistics and ethnic group differences

Means and standard deviations for acculturative stress, general life stress, bulimia, drive for thinness, and body dissatisfaction for each ethnic group are reported in Table 1. Comparisons of country of origin were conducted by categorizing participants as born in the US (assigned a value of 1) or not born in the US (assigned a value of 2). Significant differences were observed among the ethnic minority groups, X 2 (176) = 21.80, p < .01, with Asian Americans (50 %) having significantly more women reporting being born outside of the US compared to 24 % of Latinas, and 13.3 % of African American women reporting being born outside of the US One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to explore differences in the number of years lived in the US and generational status across ethnic groups, with the Bonferroni correction used for all post hoc analyses. Significant differences across ethnic groups were found for the number of years lived in the US, F(2, 75) = 5.38, p < .01, with both Asian Americans (p = .02) and Latinas (p = .02) reporting living in the US significantly less than African Americans. No significant differences among ethnic groups were found for generational status, F(2, 75) = 1.72, p = .19.

Multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) were conducted to assess differences in acculturative stress, general life stress, bulimia, drive for thinness, and body dissatisfaction across age, ethnic groups, generational status, and number of years lived in the US Post hoc analyses were conducted using the Bonferroni correction. Analyses revealed significant differences across ethnic groups for acculturative stress, F(2, 238) = 8.87, p < .001, general life stress, F(2, 238) = 6.17, p = .002, bulimia, F(2, 238) = 4.26, p = .15, and body dissatisfaction, F(2, 238) = 3.20, p = .04. Specifically, Asian Americans reported significantly higher levels of acculturative stress than African Americans and Latinas (ps < .001). For general life stress, Asian Americans (p = .003) and African Americans (p = .037) reported significantly higher levels of general life stress than Latinas. In terms of bulimia, Asian Americans reported significantly higher levels of bulimic symptoms when compared to African Americans (p = .012). For body dissatisfaction, African Americans reported significantly lower levels of body dissatisfaction than Latinas (p = .038). No significant ethnic differences were noted for drive for thinness. No significant differences were noted for any of the study variables across age, F(8, 231) = 1.43, p = .16, number of years lived in the US, F(16, 61) = 0.96, p = .59, or generational status, F(6, 71) = 1.39, p = .09.

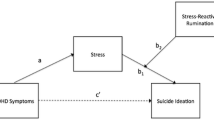

Acculturative stress as a moderator of body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptomatology

Hierarchical regression analyses were used to determine if acculturative stress moderated the relationship between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms among different ethnic minority groups. Results from these analyses are presented in Table 2. In Step 1 of the hierarchical regression, body dissatisfaction and acculturative stress were entered as predictors of bulimia symptoms. Consistent with previous research, when all ethnic groups are combined, body dissatisfaction, acculturative stress and their interaction term significantly predict bulimic symptoms. When analyses were conducted for each ethnic group separately, both body dissatisfaction and acculturative stress were found to be significant predictors of bulimic symptoms among African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinas in Step 1. However, in Step 2 of the regression when the interaction of body dissatisfaction and acculturative stress was entered as the predictor of bulimic symptoms, the interaction was only found to be a significant predictor of bulimic symptoms among African American women (p < .05). As shown in Fig. 1, examination of this interaction indicated that African American women with greater levels of acculturative stress had higher levels of body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms. For Fig. 1, body dissatisfaction and acculturative stress were divided using a median split. This interaction being significant among African American women only is contrary to the original hypothesis that acculturative stress would moderate the relationship between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms among each ethnic minority group.

To assess if lack of findings were due to inadequate statistical power to detect effects, post hoc power analyses for multiple regression were conducted for each ethnic group. For all three ethnic groups, the observed statistical power was greater than .98 for three predictors with a probability level of 0.05, indicating this study had adequate statistical power to detect the effects observed.

Relationship among acculturative stress, general life stress, and eating disorder symptoms

Associations among acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms of bulimia, body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness were assessed before and after controlling for general life stress using zero-order (Table 3) and partial correlations (Table 4). Correlations between acculturative stress and general life stress varied across ethnic groups, with the association being highest among Asian Americans (r = .33, p < .01), followed by African Americans (r = .24, p < .05). The correlation between acculturative stress and general life stress for Latinas was non-significant (r = .01, p > .05). Among all ethnic groups, acculturative stress was significantly correlated with bulimia before controlling for general life stress, with higher levels of acculturative stress corresponding to the endorsement of more eating disorder symptoms. Acculturative stress was also significantly and positively correlated with drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction among African Americans and Asian Americans before controlling for general life stress, but not among Latinas. After controlling for general life stress, acculturative stress remained significantly correlated with bulimic symptoms across all ethnic groups. Only among African Americans did acculturative stress remain significantly correlated with body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness after controlling for general life stress. These results suggest that acculturative stress predict bulimic symptoms above and beyond general life stress among Asian Americans, African Americans, and Latinas.

Discussion

This study sought to explore the relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms among African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinas. Specifically, the current study sought to replicate and expand upon the previous Perez et al. (2002) study which indicated that acculturative stress moderates the relationship between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms among ethnic minority women (Perez et al., 2002). It is important to note that the Perez et al. (2002) combined all ethnic minority women into one group, and when analyses in this study combined the ethnic groups, the findings were replicated. However, results from the current study also assessed the relationship between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms separately for each ethnic group and the results only support some of the findings from Perez and colleagues: acculturative stress only moderated the relationship between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms among African Americans, but not among Latinas or Asian Americans. These findings are important and serve to further elaborate on the relationship between acculturative stress, body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms, highlighting that these relationships may differ across ethnic groups. While the findings from the current study did not entirely replicate results from previous research, the finding that acculturative stress moderates the relationship between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms among African American women adds to the growing literature suggesting that the presence of acculturative stress is associated with a host of physical health symptoms (Bauer et al., 2012; Finch & Vega, 2003), mental health symptoms (Joiner & Walker, 2002; Ortega et al., 2000), and eating disorder symptoms (Perez et al., 2002) among African Americans.

When exploring differences among the ethnic groups, it was noted that African American women reported being born in the US or living in the US longer than both Asian American and Latina women and yet, the African American women appear to be experiencing greater negative effects of acculturative stress than women from the other ethnic groups. Even though African Americans use the same language and share similar core values with the dominant White culture in the US, Anderson (1991) argues that African Americans have not completely assimilated into American culture and Afrocentrism in African American culture stands in contrast to the Eurocentric American culture. Thus, African Americans born in the US may still report high levels of acculturative stress. Indeed, African American college students typically attend predominantly White universities that are comprised of White American value systems (Jones, 1991) that are discrepant from their culture and the incompatibility of these two sets of values potentially creates acculturative stress (Thompson et al., 2010). Two risk factors have been found to predict acculturative stress in African American college students. Anderson and colleagues found that the higher the degree of racial (Afrocentric) socialization during childhood predicts higher levels of acculturative stress among African American university students (Thompson et al., 2010). A separate study also found that family pressure for participants to not acculturate, maintain ethnic group language, and perception of acting White predicted acculturative stress even when acculturation and general stress were controlled for among African American college students attending a predominantly White university (Thompson et al., 2010). Since the body image ideal for women of the African American culture is significantly larger than the body image ideal of White American culture (Altabe, 1998; Perez & Joiner, 2003), attainment of the thin ideal through eating disorder behaviors may be perceived by family as acting White and lead to greater familial conflict and acculturative stress among African Americans. In contrast, Latinas and Asian American women have body image ideals that are closer to the thin ideal of US American Society (Altabe, 1998) and may experience less familial conflict for the attainment of the thin ideal when compared to African Americans. It is plausible that the link between acculturative stress and eating disorder behaviors is stronger among African American women than other ethnic groups due to familial perception of thinness as a White Eurocentric ideal.

Another plausible hypothesis for why acculturative stress may have only moderated the relationship between bulimic symptoms and body dissatisfaction among African American women is that African American women in this study internalized the White, thin-ideal body type that Western society encourages individuals to attain more so than the other ethnic groups. If this is the case, African American women are likely at greater risk for experiencing body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms as a result of stress and attempting to attain this ideal body type. Further researcher to elucidate the mechanism behind the differential relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms across ethnic groups is needed.

The current study also sought to assess the distinction between acculturative stress and general life stress in predicting eating disorder symptoms. When comparing levels of acculturative stress among different ethnic groups, results indicate that acculturative stress is significantly related to bulimic symptoms among Asian Americans, African Americans, and Latinas, even after controlling for general life stress. Only among African Americans did acculturative stress continue to be significantly correlated with body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness after controlling for general life stress. These findings suggest that there is something unique to acculturative stress in contributing to bulimic symptoms across all ethnic groups in this study and support the incorporation of culturally relevant discussions and problem solving within the treatment process for bulimic symptoms (Gilbert, 2003), particularly for African American women where acculturative stress was uniquely related to a wider array of eating disorder symptoms. However, further research is needed to continue to tease apart the overlap and distinction between acculturative stress and general life stress, as it relates to eating disorder symptoms, and specifically test if eating disorder treatments are enhanced by the inclusion of culturally relevant problem solving.

An interesting finding from this study was that when comparing all ethnic groups it appeared that Asian American women report the most acculturative and general life stress. This finding is consistent with previous research that has indicated that Asian Americans tend to report significantly higher levels of distress when compared to other minority groups (Poyrazli et al., 2004). Cho (2003) cited a variety of reasons why Asian college students tend to report higher levels of distress. For example, Asian students who endorsed coming to the US for education purposes and living alone reported higher levels of distress and depressive and suicidal symptoms, while those who reported living with their parents in the US reported less distress and depressive and suicidal symptoms. Thus, social support may be an important buffer for Asian students acculturating to the US English proficiency has also been identified as a predictor of adjustment among Asians who immigrate to the US, with greater difficulty in developing proficiency in the English language predicting higher levels of stress related to acculturation (Yoon et al., 2008, 2010). In addition to these possible explanations, within the current sample, Asian American women reported living in the US for a shorter period of time than African American and Latina women. This difference in length of time spent living in the US among Asian American women could also account for higher levels of acculturative stress within this ethnic group, as these women have had less time to adjust to the new culture they are now living in.

The findings from the study provide important clinical implications for ethnic minority women who present for therapy. Specifically, when any ethnic minority woman presents for therapy, if acculturative stress is endorsed, body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms should also be assessed. Clinicians may not typically assess for body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms when the presenting problem focuses on acculturative stress. However, the findings from this study suggest that ethnic minority women who are experiencing acculturative stress may also be experiencing difficulty with body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms, which could be addressed within treatment. Treatments designed to reduce acculturative stress and increase social support may reduce the expression of eating disorder symptoms among minority women. It is also plausible within treatments for eating disorder symptoms the inclusion of acculturative stress and social support as treatment targets may increase overall treatment effects producing greater reduction of symptoms of both acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms.

While the current study increases our understanding of the negative consequences associated with acculturative stress, the present findings must be interpreted with several caveats in mind. The study consisted of a sample containing entirely undergraduate women, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Non-collegiate women may experience different acculturative stress issues, which in turn may impact the role of acculturative stress as a moderator of body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms. This study was also correlational in nature which eliminates the ability to investigate causality or establish temporal sequence among acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms. A large portion of participants in the current study also did not report their generational status or country of origin, which may have influenced the exploration of these variables as potential confounds within the current study. Additionally, there was a lack of within ethnic group analyses, since the current study only classified women as being born in the US or not. Future studies should further categorize minority women into more distinct categories (e.g., Chinese, Japanese, Korean vs. Asian), as it is possible that the role of acculturative stress, body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms differs based on country of origin.

Also, a number of variables that have previously been found to be associated with acculturative stress and/or disordered eating symptoms were not assessed within the current study. Specifically, the type of acculturation (i.e., biculturalism, assimilation) women in the current sample were attempting to achieve was not assessed. It is plausible that acculturative stress only serves as a moderator of body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms among minority women who are attempting to achieve biculturalism or assimilation, and not among those who separate from the dominant culture. Participants’ body mass index has not been included in most research investigating acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms, including this study, and therefore has not been assessed as a potential confounding variable. Finally, previous research has found other factors, such as internalization of the White thin-ideal body type (Warren et al., 2010), gender identity problems and difficult family relationships (Kuba et al., 2012) to be significant predictors of disordered eating symptoms among Latinas. These relationships were not assessed within the current study. Thus, future research should explore the relationships between acculturative stress, general life stress, and eating disorder symptoms across ethnicity while concurrently assessing for additional variables, such as type of acculturation, BMI, thin-ideal internalization, gender identity problems, and family relationships.

In conclusion, the current study found acculturative stress served as a moderator between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms. However, this moderation only occurred among African American women. Asian American and Latina women also endorse experiencing acculturative stress, general life stress, and eating disorder symptoms. The current study also found that acculturative stress predicted bulimic symptoms among African American, Asian American, and Latina women above and beyond general life stress. Findings from this study highlight the need for further research investigating the relationship of acculturative stress, general life stress, and eating disorder symptoms among ethnic minority women.

References

Abrams, K. K., Allen, L., & Gray, J. J. (1993). Disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, psychological adjustment, and ethnic identity: A comparison of black and white female college students. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 14, 49–57. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199307)14:1<49:AID-EAT2260140107>3.0.CO;2-Z

Agliata, D., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (2004). The impact of media exposure on males’ body image. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 7–22. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.1.7.26988

Alegria, M., Woo, M., Cao, Z., Torres, M., Meng, X., & Striegel-Moore, R. (2007). Presence and correlates of eating disorders in Latinos in the United States. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 15–21. doi:10.1002/eat.20406

Alloy, L. B., & Clements, C. M. (1992). Illusion of control: Invulnerability to negative affect and depressive symptoms after laboratory and natural stressors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 234–245.

Altabe, M. (1998). Ethnicity and body image: Quantitative and qualitative analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 23, 153–159. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199803)23:2<153:AID-EAT5>3.0.CO;2-J

Anderson, L. P. (1991). Acculturative stress: A theory of relevance to Black Americans. Clinical Psychology Review, 11, 685–702. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(91)90126-F

Bardone-Cone, A. M., & Boyd, C. A. (2007). Psychometric properties of eating disorder instruments in Black and White young women: Internal consistency, temporal stability, and validity. Psychological Assessment, 19, 356–362. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.356

Bauer, A. M., Chen, C., & Alegria, M. (2012). Prevalence of physical symptoms and their association with race/ethnicity and acculturation in the United States. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34, 323–331. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.02.007

Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Reports, 88, 354–364. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.88.4.354

Bernert, R. A., Merrill, K. A., Braithwaite, S. R., Van Orden, K. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2007). Family life stress and insomnia symptoms in a prospective evaluation of young adults. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 58–66. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.58

Berry, J. W. (1998). Acculturative stress. In P. B. Organista, K. M. Chun, & G. Marín (Eds.), Readings in ethnic psychology (pp. 117–122). New York: Routledge.

Bruch, H. (1973). Psychiatric aspects of obesity. Psychiatric Annals, 3, 6–10.

Cachelin, F. M., Veisel, C., Barzegamazari, E., & Streigel-Moore, R. H. (2000). Disordered eating, acculturation, and treatment-seeking in a community sample of Hispanic, Asian, Black, and White women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 233–244. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb0020

Cash, T. F., & Deagle, E. A. (1997). The nature and extent of body-image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 22, 107–125. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199709)22:2<107:AID-EAT1>3.0.CP;2-J

Chamorro, R., & Flores-Ortiz, Y. (2000). Acculturation and disordered eating patterns among Mexican American women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28, 125–129. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(200007)28:1<125:AID-EAT16>3.0.CO;2-9

Cho, Y. B. (2003). Suicidal ideation, acculturative stress, and perceived social support among Korean adolescents. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B. Sciences & Engineering. 63(8-B), 3907.

Constantine, M. G., Okazaki, S., & Utsey, S. O. (2004). Self-concealment, social self-efficacy, acculturative stress, and depression in African, Asian, and Latin American international college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74, 230–241. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.74.3.230

Crago, M., & Shisslak, C. M. (2003). Ethnic differences in dieting, binge eating, and purging behaviors among American females: A review. Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment and Prevention, 11, 289–304. doi:10.1080/10640260390242515

Crockett, L. J., Iturbide, M. I., Torres Stone, R. A., McGinley, M., Raffaelli, M., & Gustavo, C. (2007). Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: Relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 347–355. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.347

Cusumano, D. L., & Thompson, J. K. (1997). Body image and body shape ideals in magazines: Exposure, awareness and internalization. Sex Roles, 37, 701–721. doi:10.1007/BF02936336

Davis, C., & Katzman, M. A. (1999). Perfection as acculturation: Psychological correlates of eating problems in Chinese male and female students living in the United States. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 25, 65–70. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199901)25:1<65:AID-EAT8>3.0.CO;2-W

Dolan, B. (1991). Cross-cultural aspects of anorexia nervosa and bulimia: A review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 10, 67–78. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199101)10:1<67:AID-EAT2260100108>3.0.CO;2-N

Fairburn, C. G., & Beglin, S. J. (1990). Studies of the epidemiology of bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 401–408.

Fairburn, C. G., Peveler, R. C., Jones, R., Hope, R. A., & Doll, H. A. (1993). Predictors of 12-month outcome in bulimia nervosa and the influence of attitudes to shape and weight. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 696–698. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.61.4.696

Fairburn, C. G., Stice, E., Cooper, Z., Doll, H. A., Norman, P. A., & O’Conner, M. E. (2003). Understanding persistence in bulimia nervosa: A 5-year naturalistic study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 103–109. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.103

Finch, B. K., & Vega, W. A. (2003). Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health, 5, 109–117. doi:10.1023/A:1023987717921

Fisher, M., Pastore, D., Schneider, M., & Pegler, C. (1994). Eating attitudes in urban and suburban adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16, 67–74. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199407)16:1

Franko, D. L., Becker, A. E., Thomas, J. J., & Herzog, D. B. (2007). Cross-ethnic differences in eating disorder symptoms and related distress. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 156–164. doi:10.1002/eat.20341

Fuertes, J. N., & Westbrook, F. D. (1996). Using the Social, Attitudinal, Familial and Environmental (S.A.F.E.) Acculturation Stress Scale to assess adjustment needs of Hispanic college students. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 29, 67–76.

Furukawa, T. (1994). Weight changes and eating attitudes of Japanese adolescents under acculturative stresses: A prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 15, 71–79. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199401)15:1

Garner, D. M., Olmstead, M. P., & Polivy, J. (1983). The eating disorder inventory: A measure of cognitive-behavioral dimensions of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. In P. L. Darby, P. E. Garfinkel, D. M. Garner, & D. V. Coscina (Eds.), Anorexia nervosa: Recent developments in research (pp. 173–184). New York: Liss.

Gilbert, S. C. (2003). Eating disorders in women of color. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 444–455. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpg045

Gordon, K. H., Castro, Y., Sitnikov, L., & Holm-Denoma, J. M. (2010). Cultural body shape ideals and eating disorder symptoms among White, Latina, and Black college women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 135–143. doi:10.1037/a0018671

Grabe, S., & Hyde, J. S. (2006). Ethnicity and body dissatisfaction among women in the United States: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 622–640. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.4.622

Guinn, B., Semper, T., & Jorgensen, L. (1997). Mexican-American female adolescent self-esteem: The effect of body image, exercise behavior, and body fatness. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 19, 517–526. doi:10.1177/07399863970194009

Hodes, M., Jones, C., & Davies, H. (1996). Cross-cultural differences in maternal evaluation of children’s body shapes. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 19, 257–263. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199604)19:3<257:AID-EAT4>3.0.CO;2-L

Hrabosky, J. I., & Grilo, C. M. (2007). Body image and eating disordered behavior in a community sample of Black and Hispanic women. Eating Behavior, 8, 106–114. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.02.005

Joiner, G. W., & Kashubeck, S. (1996). Acculturation, body image, self-esteem, and eating disorder symptomatology in adolescent Mexican-American women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 419–435. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00309.x

Joiner, T. E., & Walker, R. (2002). Construct validity of a measure of acculturative stress in African Americans. Psychological Assessment, 14, 462–466. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.462

Jones, L. T. (1991). African-American students’ help-seeking behavior: A comparative study based on academic performance and class level. Dissertation Abstracts International, 52, 2051–2052.

Kelly, N. R., Mitchell, K. S., Gow, R. W., Trace, S. E., Lydecker, J. A., Bair, C. E., et al. (2012). An evaluation of the reliability and construct validity of eating disorder measures in White and Black women. Psychological Assessment, 24, 608–617. doi:10.1037/a0026457

Kiang, L., Grzywacz, J. G., Marin, A. J., Arcury, T. A., & Quandt, S. A. (2010). Mental health in immigrants from nontraditional receiving sites. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 386–394. doi:10.1037/a0019907

Kirmayer, L., & Sartorius, N. (2007). Cultural models and somatic syndromes. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69, 832–840. doi:10.1097/PSY.obo13e31815b002c

Kuba, S. A., Harris-Wilson, D. J., & O’Toole, S. K. (2012). Understanding the role of gender and ethnic oppression when treating Mexican American women for eating disorders. Women & Therapy, 35, 19–30. doi:10.1080/02703149.2012.634715

Landrine, H., & Klonoff, E. A. (1996). African American acculturation: Deconstructing race and reviving culture. Thousan Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Lawrence, C. M., & Thelen, M. H. (1995). Body image, dieting, and self-concept: Their relation in African-American and Caucasian children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 24, 41–48. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2401_5

le Grange, D., Telch, C. F., & Agras, W. S. (1997). Eating and general psychopathology in a sample of Caucasian and ethnic minority subjects. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 21, 285–293. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199704)21:3

Lester, R., & Petrie, T. A. (1998). Physical, psychological, and societal correlates of bulimic symptomatology among African American college women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45, 315–321. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.315

Lopez, E., Blix, G. G., & Blix, A. G. (1995). Body image of Latinas compared to body image of non-Latina White women. Health Values, 19, 3–10.

Mena, F. J., Padilla, A. M., & Maldonado, M. (1987). Acculturative stress and specific coping strategies among immigrant and later generation college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9, 207–225. doi:10.1177/07399863870092006

Metalsky, G. I., & Joiner, T. E, Jr. (1992). Vulnerability to depressive symptomatology: A prospective test of the diathesis-stress and causal mediation components of the hopelessness theory of depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 667–675. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.667

Mintz, L. B., & Betz, N. E. (1988). Prevalence and correlates of eating disordered behaviors among undergraduate women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35, 463–471.

Mitchell, J. E., & Crow, S. (2006). Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Current Opinions in Psychiatry, 19, 438–443.

Moradi, B., & Subich, L. M. (2002). Perceived sexist events and feminist identity development attitudes: Links to women’s psychological distress. The Counseling Psychologist, 30, 44–65. doi:10.1177/0011000002301003

Neff, L. J., & Hoppe, S. K. (1993). Race/ethnicity, acculturation, and psychological distress: Fatalism and religiosity as cultural resources. Journal of Community Psychology, 21, 3–20. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(199301)21:1<3:AID-JCOP2290210102>3.0.CO;2-9

Nicdao, E. G., Hong, S., & Takeuchi, D. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders among Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 22–26. doi:10.1002/eat.20450

O’Neill, S. K. (2003). African American women and eating disturbances: A meta-analysis. Journal of Black Psychology, 29, 3–16. doi:10.1177/0095798402239226

Ortega, A. N., Rosenheck, R., Alegria, M., & Desai, R. A. (2000). Acculturation and the lifetime risk of psychiatric and substance use disorders among Hispanics. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188, 728–735. doi:10.1097/00005053-200011000-00

Padilla, A., Wagatsuma, Y., & Lindholm, K. (1985). Acculturation and personality as predictors of stress in Japanese Americans. Journal of Social Psychology, 125, 295–305.

Paukert, A. L., Pettit, J. W., Perez, M., & Walker, R. L. (2006). Affective and attributional features of acculturative stress among ethnic minority college students. Journal of Psychology, 140, 405–419. doi:10.3200/JRLP.140.5.405-419

Perez, M., & Joiner, T. E. (2003). Body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating in black and white women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 33, 342–350. doi:10.1002/eat.10148

Perez, M., Voelz, Z. R., Pettit, J. W., & Joiner, T. E. (2002). The role of acculturative stress and body dissatisfaction in predicting bulimic symptomatology across ethnic groups. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 442–454. doi:10.1002/eat.10006

Pike, K. M., Dohm, F. A., Striegel-Moore, R. H., Wilfley, D. E., & Fairburn, C. G. (2001). A comparison of Black and White women with binge eating disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1455–1460. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1455

Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (2002). Causes of eating disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 187–213. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135103

Poyrazli, S., Kavanaugh, P. R., Baker, A., & Al-Timimi, N. (2004). Social support and demographic correlates of acculturative stress in international students. Journal of College Counseling, 7, 73–82.

Pumariega, A. J. (1986). Acculturation and eating attitudes in adolescent girls: A comparative and correlational study. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 25, 276–279. doi:10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60238-7

Reddy, S. D., & Crowther, J. H. (2007). Teasing, acculturation, and cultural conflict: Psychosocial correlates of body image and eating attitudes among South Asian women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 45–53. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.45

Regan, P. C., & Cachelin, F. M. (2006). Binge eating and purging in a multi-ethnic community sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39, 523–526. doi:10.1002/eat.20268

Sabik, N. J., Cole, E. R., & Ward, L. M. (2010). Are all minority women equally buffered from negative body image? Intra-ethnic moderators of the buffering hypothesis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 139–151. doi:10.111/j.1471-6402.2010.01557.x

Saxe, L. L., & Abramson, L. Y. (1987). The negative life events questionnaire: Reliability and validity. Unpublished manuscript.

Silber, T. J. (1986). Approaching the adolescent patient: Pitfalls and solutions. Journal of Adolescent Health Care, 7, 31–40.

Silberstein, L. R., Striegel-Moore, R. H., Timko, C., & Rodin, J. (1988). Behavioral and psychological implications of body dissatisfaction? Do men and women differ? Sex Roles, 19, 219–232. doi:10.1007/BF00290156

Stice, E., & Shaw, H. E. (1994). Adverse effects of the media portrayed thin-ideal on women and linkages to bulimic symptomatology. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 13, 288–308.

Striegel-Moore, R. H., Dohm, F. A., Kraemer, H. C., Taylor, C. B., Daniels, S., Crawford, P. B., et al. (2003). Eating disorders in White and Black women. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1326–1331. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1326

Striegel-Moore, R. H., Silberstein, L. R., & Rodin, J. (1986). Toward an understanding of risk factors for bulimia. American Psychologist, 41, 246–263. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.41.3.246

Taylor, J. Y., Caldwell, C. H., Baser, R. E., Faison, N., & Jackson, J. S. (2007). Prevalence of eating disorders among Blacks in the national survey of American life. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 10–14. doi:10.1002/eat.20451

Thompson, J. K., & Stice, E. (2001). Thin-ideal internalization: Mounting evidence for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 181–183. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00144

Thompson, K. V., Lightfoot, N. L., Castillo, L. G., & Hurst, M. L. (2010). Influence of family perceptions of acting white on acculturative stress in African American college students. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 32, 144–152. doi:10.1007/s10447-010-9095-z

Tsai, G., & Gray, J. (2000). The eating disorders inventory among Asian-American college women. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140, 527–529. doi:10.1080/00224540009600490

Tylka, T. L., & Hill, M. S. (2004). Objectification theory as it relates to disordered eating among college women. Sex Roles, 51, 719–730. doi:10.1007/s11199-004-0721-2

Walker, R. L., Obasi, E. M., Wingate, L. R., & Joiner, T. E. (2008). An empirical investigation of acculturative stress and ethnic identity as moderators for depression and suicidal ideation in college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 75–82. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.14.1.75

Warren, C. S., Castillo, L. G., & Gleaves, D. H. (2010). The sociocultural model of eating disorders in Mexican American women: Behavioral acculturation and cognitive marginalization as moderators. Eating Disorders, 18, 43–57. doi:10.1080/10640260903439532

Warren, C. S., & Rios, R. M. (2012). The relationships among acculturation, acculturative stress, endorsement of western media, social comparison, and body image in Hispanic male college students. Psychology of Men & Masculinity (advance online publication). doi:10.1037/a0028505

Wertheim, E. H., Paxton, S. J., Schutz, H. K., & Muir, S. L. (1997). Why do adolescent girls watch their weight? An interview study examining sociocultural pressures to be thin. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 42, 345–355. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00368-6

White, M. A., & Grilo, C. M. (2005). Ethnic differences in the prediction of eating and body image disturbances among female adolescent psychiatric inpatients. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 38, 78–84. doi:10.1002/eat.20142

Wilson, G. T., Becker, C. B., & Heffernan, K. (2003). Eating Disorders. In E. J. Mash & R. A. Barkley (Eds.), Child psychopathology (2nd ed., pp. 687–715). New York: Guilford.

Yoon, E., Lee, R. M., & Goh, M. (2008). Acculturation, social connectedness, and subjective well-being. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 246–255. doi:10.1037/1099-9808.14.3.246

Yoon, E., Lee, D. Y., Koo, Y. R., & Yoo, S. (2010). A qualitative investigation of Korean immigrant women’s lives. The Counseling Psychologist, 38, 523–553. doi:10.1177/0011000009346993

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kroon Van Diest, A.M., Tartakovsky, M., Stachon, C. et al. The relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms: is it unique from general life stress?. J Behav Med 37, 445–457 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-013-9498-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-013-9498-5