Abstract

Physical activity interventions among youth have resulted in modest outcomes; thus, there is a need to increase the theoretical fidelity of interventions and hone pilot work before embarking on large scale trials. The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of a planning intervention in comparison to a standard condition on intergenerational physical activity in families with young children. Inactive families (N = 85) were randomized to either a standard condition (received physical activity guidelines and a local municipal healthy active living guide) or the intervention (physical activity guidelines, local municipal healthy active living guide + planning material) after completing a baseline questionnaire package. Sixty-five families (standard condition n = 34; intervention condition n = 31) completed the 4 week follow-up questionnaire package. Complete cases and intention to treat analyses showed that the planning intervention resulted in higher self-reported family physical activity compared to the standard condition and this was due to an increase in unstructured family activities over the 4 weeks. The results are promising and suggest that theoretical fidelity targeting parent regulation of family activity may be a helpful approach to increasing weekly energy expenditure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sustained physical inactivity has been attributed to over 25 chronic health conditions (Warburton et al. 2007) and nearly two million premature deaths every year (World Health Organization 2008), yet its prevalence is high (Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute 2004). Family-based intervention, that is physical activity changes within the family leisure-time structure, is a logical avenue for intervention. Children spend considerable time within the care of their parents; indeed parents are the “gatekeepers” of young children and their experiences during family time (Gustafson and Rhodes 2006). Parents of young children themselves are also a demographic at high risk for inactivity (Bellows-Riecken and Rhodes 2008; Rhodes et al. 2008). Thus, family-based physical activity promotion may serve to increase the energy expenditure of two critical populations.

In comparison to school-based efforts for changing youth physical activity, interventions targeting the family home environment have been relatively sparse (Kahn et al. 2002; O’Connor et al. 2009). A recent systematic review identified 35 independent studies that have focused on the family in some capacity (O’Connor et al. 2009). Only six of these studies, however, included an intergenerational (i.e., children active with parents) physical activity intervention. Unfortunately, only one of these saw significant changes in behavior from the intervention. Indeed, O’Connor et al. conclude that there is little evidence of effectiveness in changing physical activity across all 35 studies involving family.

The low performance of family physical activity interventions has been duly acknowledged in prior reviews (Dishman and Buckworth 1996; Kahn et al. 2002). There is clearly a need to improve upon prior work in terms of the intervention fidelity and to evaluate pilot trials before moving to large-scale RCTs that parallel the school-based intervention literature. An analysis of the types of interventions employed in prior work points to very similar types of interventions that included a heavy focus on education about the benefits of physical activity, some discussion/enactment of barriers and types of physical activities, followed by a self-monitoring component. While these approaches are generally grounded in the operational constructs common in our theoretical models of health behavior (Fishbein et al. 2001), the sensitivity to critical agents of change may improve the fidelity and thus the potency of interventions. For example, reviews of the literature on mediators of interventions position self-regulatory constructs (e.g., planning, contingency strategies, stimulus control) as the most consistent agents of change (Lewis et al. 2002; Rhodes and Pfaeffli 2009). Successful intervention approaches in adult populations have also shown similar results (e.g., Lippke et al. 2004; Milne et al. 2002; Prestwich et al. 2003). This present study aims to focus its intervention heavily on these self-regulation components.

From a theoretical standpoint, the premise behind these approaches follows that regulatory skills are required to tie good initial intentions to subsequent behavior (Gollwitzer and Sheeran 2006; Lippke et al. 2004; Norman and Conner 2005; Rhodes and Plotnikoff 2006; Sniehotta et al. 2005). These include but are not limited to the specifics of a behavioural plan (e.g., what, when, where, with who) and the problem solving and monitoring of behavioural action. While educational approaches on the benefits of physical activity and skill development may help to create positive attitudes and perceived behavioural control/self-efficacy, these approaches foster intentions but do not necessarily sustain intention/motivation into behavioral enactment (Ajzen and Fishbein 2005; Gollwitzer and Sheeran 2006). In terms of family physical activity, parents are plagued with physical activity barriers that compete for their time and attention (Bellows-Riecken and Rhodes 2008; Rhodes et al. 2008) and successful physical activity has been correlated with regulation of these barriers as opposed to attitudinal/knowledge variables (McIntyre and Rhodes 2009). Thus, it appears that self-regulatory, or in this case, family regulatory approaches may also be the critical agent for enacting change rather than interventions aimed at increasing attitudes. This premise, however, has yet to be tested in family-based intervention initiatives.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the effect of a planning intervention in comparison to a standard condition on intergenerational physical activity in families with young children. Based on the argument that parents are the gatekeepers of activity and prior research showing the efficacy of planning interventions, it was hypothesized that the group who received the planning intervention would report more family-based physical activity compared to the group who did not receive this intervention. It was subsequently hypothesized that intention and perceived behavioural control would not change as a result of the two interventions based on the premise that planning ties motivation to behavior but is not a motivational factor itself (Norman and Conner 2005).

Method

Study design and participants

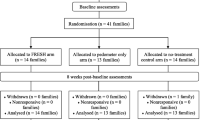

A randomized controlled trial was conducted with measurements at baseline and 4 weeks post-intervention. Primary outcome measures were weekly intergenerational family physical activity frequency, total minutes of intergenerational family physical activity, frequency and total minutes of formal family physical activity (e.g., structured activities like parent–child swimming lessons, skating, kindergym, or parent and tot gymnastics), frequency and total minutes of informal family physical activity (e.g., family walks, bike rides, playing at parks or in the backyard), intention to engage in family intergenerational physical activity, and perceived control over family intergenerational physical activity. Respondents were 107 families who met the inclusion criteria of being married or common law parents, having a child (or children) between the ages of four and 10 and who self-identified room to improve weekly family physical activities (<4 times per week @ 60 min duration). Our goal of fostering intergenerational activity was deemed most promising with families who had children between the ages of four and 10. This age group is highly dependent on their parents for transportation and most forms of activity. Tweens are likely beginning to spend leisure-time with peers (Gustafson and Rhodes 2006) while toddlers are less likely participate in sustained intergenerational physical activity due to their very intermittent movement patterns (Temple et al. 2009). Respondents were provided with a baseline questionnaire package and 22 families were excluded from the study due to self-reporting family intergenerational physical activity above the initial inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1). The remaining 85 families were randomly assigned to either the planning + standard intervention group (n = 42 families) or the standard (comparison) group in a computer-determined sequence. Randomization was concealed until actual exposure to the intervention. Recruitment, randomization to groups and mailing/contact with participants were performed by an independent research assistant. The researchers were blind to the assigned study condition during the intervention period. The study was approved by the first author’s IRB and all participants provided initial and ongoing informed consent (at follow-up) during participation.

Procedure

Potential participants were invited to participate in the study by means of flyers and poster advertisements about a family physical activity and health study. A list of all daycares, recreation centres, preschools and elementary schools in the Capitol Region District of British Columbia was used as the sampling frame for distribution. The study advertisement and removable brochures were placed in the community bulletin boards and/or front desks of these institutions for parents to learn about the study. Recruitment in this fashion was ongoing from January 2007 until December 2008. Interested participants contacted a research assistant via phone or email in which the study purpose, elements, inclusion criteria and randomization procedure were explained. Participants were then mailed a baseline questionnaire package. Within 1 week of completion of the baseline questionnaire by the contact parent for the family, families were randomized to receive intervention or standard group material and this was mailed to the family home. Families were asked to read the material/follow the intervention instructions over the following 4 weeks. After 4 weeks, the follow-up questionnaire was mailed to participants. This included similar measures to the baseline questionnaire and process evaluation information (i.e., use of the material provided, usefulness, barriers to use). Respondents who did not send back their follow-up questionnaire within a week received a reminder phone call and email, followed by a second reminder questionnaire 2 weeks later similar to the total design method (Dillman 1983). The participants received a $10 CND honorarium after completion of the baseline questionnaire followed by a $15 CND honorarium and a thank you letter after completion of the follow-up questionnaire.

Intervention

The standard (comparison group) package consisted of Canada’s family guide to physical activity guidelines (Public Health Agency of Canada 2002) recommending 90 min of activity a day in bouts as short as 5 to 10 min for children and a breakdown of ways for the family to achieve this physical activity (structured, unstructured, endurance, strength, flexibility activities, less than 60 min of sustained sedentary activity, reduce screen viewing by 30 min per day) commensurate with this guide. This group also received the active living recreation guide for their local recreation centre. These are extensive and thorough information guides of the local facilities and available child/parent programs and classes that are published quarterly by the municipalities of the Capitol Region District.

The intervention condition received the same documents as the comparison condition but was also provided with family physical activity planning material. This material included educational content (workbook how to plan for family physical activity) and practical material to create a plan (i.e., a colourful dry erase wall calendar for family activities with fridge magnets). The education material for planning was based on several streams of prior work in the adult physical activity literature. Families were instructed to plan for “when,” “where,” “how,” and “what” physical activity will be performed commensurate with the creation of implementation intentions (e.g., Milne et al. 2002; Prestwich et al. 2003). The workbook, however, also focused on problem solving barriers to physical activity which is more akin to coping planning and traditional goal setting (Locke and Latham 1990; Sniehotta et al. 2005, 2006; Strecher et al. 1995). The design of all material was created for this study and featured graphic design and colour images that represent family physical activity.

Measurement

The questionnaire asked for a contact parent to complete all measures on behalf of the family across the study. In cases with multiple children and split parent activities, we instructed the contact participant to consider their activity with the youngest child (in the range of four to 10 years old) and to not act as a proxy estimate of their spouse or older child’s activity when the contact parent was not present. This was deemed necessary to aid in consistency across measurement although it may bias (downward) the estimates of total family physical activity. For the social cognitive constructs (intention, perceived behavioral control), the contact parent was asked to consider activities at or above Canada’s guidelines of at least four bouts of physical activity per week accumulating at least 30 min of activity per bout (Public Health Agency of Canada 2002). Because children may move in short bouts, we used the accumulation phrasing in an attempt to capture total movement.

Leisure-time physical activity. Contact parent personal leisure-time physical activity was measured using the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) (Godin et al. 1986). The GLTEQ contains three open-ended questions regarding the frequency of mild (e.g., easy walking), moderate (e.g. fast walking) and vigorous (e.g. jogging) physical activity. The duration was adapted from 15 min to greater to or equal to 30 min per session based on current public health guidelines for adults (Health Canada 2002). No self-reported instrument for collective (i.e., intergenerational) family physical activity was available during the creation of this study. Thus a measure was created for this study using the GLTEQ and well as the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (Craig et al. 2003) and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire (CDC 2001) as response templates. This includes an open estimate of frequency and duration (min) in a typical week for parent respondents to complete. Canada’s guide for family physical activity highlights structured (parent–child swimming lessons, skating, kindergym, or parent and tot gymnastics) and unstructured (family walks, bike rides, playing at parks or in the backyard) physical activities so separate questions were created for each type. Final outcome measures included total minutes (frequency x duration) and frequency of bouts meeting or exceeding Canada’s guidelines, as well as an amalgam composite measure of the two categories to create total family physical activity weekly frequency and total weekly family physical activity minutes scores.

Intention was measured with two items used in prior work with the theory of planned behavior (Courneya and McAuley 1994; Rhodes et al. 2006). These included: (1) “how committed are you to participating regularly in family physical activity over the next month?” from extremely uncommitted to extremely committed on a seven-point scale and (2) “I intend to engage in regular family-based physical activity ___ times per week over the next month.” The aggregate measure had acceptable reliability (α = .71).

Perceived Behavioral Control was measured using two items: “If you were really motivated, how controllable would it be for you to participate in regular family physical activity over the next month” from extremely uncontrollable to extremely controllable on a seven point scale and “If you were really motivated, how confident are you that you could participate in regular family-based physical activity over the next month” rated from extremely unconfident (1) to extremely confident (7). These items were constructed to adhere to the suggestions of Ajzen (2002) and have been validated by Rhodes and Courneya (2003, 2004). Internal consistency for the aggregate measure was acceptable (α = .84).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population. Point-biserial correlations, t-tests, and Chi-square tests of proportions were conducted to test for selective drop-out (coded 0/1) and equality of study groups at baseline. Repeated measures analyses of variance were used to test the primary outcome variables (perceived behavioral control, intention, informal physical activity weekly frequency, informal physical activity weekly total minutes, structured physical activity weekly frequency, structured physical activity weekly total minutes, total family weekly physical activity frequency, and total family weekly physical activity minutes) across time by group. Probability alpha was set P < .05; the study was powered to detect a small effect size (f = .11) considering this alpha and a power of .80 (Cohen 1992) and considering a correlation between measures of r = .75. The study was powered to detect a comparable effect size (f = .14) when considering our attrition (see Results section). Complete case analysis was conducted and presented. Subsequently, an intention to treat (ITT) analysis was conducted using a baseline carried forward procedure to substitute missing values at posttest.

Results

Participant flow

The 85 families who met the study inclusion criteria and completed the baseline questionnaire package were randomly assigned to the standard comparison group (n = 43) and the intervention group (n = 42) (Fig. 1). Seventy-nine percent of the comparison group families and 74% of the intervention group families completed the posttest questionnaire package; these numbers were not significantly different between the groups. Loss to follow-up was not associated with any demographic variable or intention and perceived behavioral control but those who did not respond at follow-up reported lower baseline unstructured family physical activity frequency (r = .25, P < .05), total minutes of unstructured family physical activity (r = .23, P < .05) and total frequency (r = .23, P < .05) minutes of family physical activity (r = .23, P < .05) compared to those who completed the study (see Table 1). The interaction between baseline variables, missingness, and group assignment, however, was not significant. The final sample available for complete case analysis was N = 65 (standard comparison group = 34; intervention group = 31).

Baseline characteristics of respondents

Baseline characteristics of the family and the contact parent for the family can be found in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the standard comparison group and the intervention group, supporting the randomization procedure. Contact parents were in their late 30 s, typically the mother of the household, and most had completed a college degree. The families generally reported two children between the ages of four and 10 years old and most reported some form of formal care provisions (school or daycare) for their children during the working day. The contact parents themselves were quite inactive, with over 60% of the sample reporting activity levels below Canada’s recommended guidelines and a mean BMI in the overweight category (i.e., 25–29.99) (Health Canada 2002).

Exposure to the intervention

In terms of an intervention manipulation and exposure check, 63 of the 65 families reported reading the physical activity guide recommendations (Public Health Agency of Canada 2002) and all parents who read the recommendations rated it as useful (18% very useful, 48% somewhat useful, 31% somewhat useful). Fifty-eight of the 65 families read their local active living and recreation guide provided and 52% of the sample reported actually using the guide to book family activities. There were no differences by group assignment on these responses. For the intervention condition, 84% of the families (26) reported using the planning material provided and 61% (19 families) reported that they posted the planning calendar on their refrigerator. The most common reasons reported for not using the material were laziness (n = 3), being too busy (n = 5) and forgetting (n = 2).

Effects on behavior and determinants

Results of the intervention on the primary outcomes can be found in Table 3. The intervention resulted in significant time effects for all parent-reported family physical activity measures; these results favoured increases in physical activity from baseline to 4 weeks post-test (F = 4.23 to 17.63; η2 = .06 to .22). Follow-up univariate tests, however, did not support significant differences over time for the standard comparison group. By contrast, the intervention group, reported significantly higher informal/unstructured physical activity frequency (F = 7.31; η2 = .11) and total minutes (F = 6.49; η2 = .09) which translated into significantly higher total family physical activity frequency (F = 5.31; η2 = .08) and total minutes (F = 4.26; η2 = .06) compared to the standard condition in time x group interactions. No significant differences were identified for structured family physical activity, intention, or perceived control.

Results using ITT data showed similar results in terms of the main effect over time (F = 3.55 to 13.77; η2 = .04 to .14); only the results from unstructured/informal family physical activity were no longer significant. The results of the intervention effect over the standard comparison group (i.e., time × group interaction) were maintained for unstructured/informal family physical activity frequency (F = 6.50, P < .01; η2 = .07) and total minutes (F = 5.24, P < .05; η2 = .06) but this no longer translated into significant differences in total family physical activity frequency or total minutes.

Discussion

Physical activity interventions among families have resulted in modest outcomes (O’Connor et al. 2009; Van Sluijs et al. 2007); thus, there is a need to increase the theoretical fidelity of the interventions and hone pilot work before embarking on large scale trials. The purpose of this study was to examine the short-term effect of a planning intervention in comparison to a standard condition on intergenerational physical activity in families with young children aged four to ten.

Based on the argument that parents are the gatekeepers of activity and prior research showing the efficacy of planning interventions, it was hypothesized that the group who received the planning intervention would report more family-based physical activity compared to the group who did not receive this intervention. This hypothesis was generally supported by our results. Self-reported family physical activity frequency and total weekly minutes were significantly higher in the planning condition from baseline to 4-weeks posttest in comparison to the standard condition that received physical activity guideline and local active living guide/calendar information. The effect amounted to an additional average of 60 min of unstructured family physical activity per week in the planning condition but it was not from additional structured physical activity (e.g., family classes at a recreation centre). The change results can be interpreted as a medium to large effect size (Cohen 1992). By contrast, the informational packet given to the standard comparison condition did not result in significant differences in family physical activity over time.

The results of this study are generally commensurate with prior reviews among adult populations that demonstrate the efficacy of self-regulatory approaches on physical activity behavior (Lewis et al. 2002; Rhodes and Pfaeffli 2009). This study, however, extends this principle to the family collective under the assumption that parents are the primary gate-keepers of physical activity for their children (Gustafson and Rhodes 2006). That is, family physical activity is dependent upon the planning and regulatory capabilities of the parents and if these can be improved, subsequent increases in physical activity will follow. Future research may benefit from extending these conditions to examine the role that environmental aspects, such as access to recreation centres and parks, may have on physical activity planning. Correlational research has shown that access to recreation moderates the intention-behavior relationship (Rhodes et al. 2006, 2007) with those who perceive less access showing a lower correlation than those who perceive high access. It would be interesting to investigate whether family-regulatory interventions can lessen this interaction.

It was also hypothesized that intention and perceptions of behavioral control (while holding motivation constant) would not change based on the premise that planning ties motivation to behavior but is not necessarily a motivational factor itself. Our results supported this conjecture. Intention and perceived behavioral control, generally considered the antecedents of behavioral action in most of our popular theories of health behavior (Bandura 2004; Fishbein et al. 2001; Noar and Zimmerman 2005), were not significantly different across time or by condition. Our findings support a growing correlational (e.g., Lippke et al. 2004; Norman and Conner 2005; Rhodes and Plotnikoff 2006; Rhodes et al. 2008; Sniehotta et al. 2005) and experimental (e.g., Milne et al. 2002; Prestwich et al. 2003; Sniehotta et al. 2006) literature that demonstrates the importance of intermediary constructs, such as regulatory processes, between intention and behavior. Educational and informational approaches to increasing physical activity may have utility in raising intentions, but these approaches may be incongruent with the types of participants who volunteer for research trials, presumably people with intentions to change their behavior. This conception leads to promotion tactics that may be different for those needing help with initial action planning (creating intentions) from those who need help with action control (translating intentions into behavior) (Ajzen and Fishbein 2005; Rhodes et al. 2003). Careful consideration of this level of theoretical fidelity in future intervention efforts may be prudent.

It is important to note that exposure to the intervention was generally effective from the results of our process evaluation. Over 80% of the intervention participants reported using the planning material provided. Identifying barriers to use, however, can be useful for understanding additional intervention approaches that may be needed. In this case, laziness, busyness/lack of time, and forgetfulness were cited as the most common barriers. It is interesting that forgetfulness was mentioned as a barrier because the implementation intention component of planning (e.g., who, where, what, when) is theorized to improve the automaticity of action and reduce forgetting (Gollwitzer and Sheeran 2006). Still, in this case forgetfulness may represent lack of time within the busy lives of parents. Time barriers due to work and domestic duties are generally considered the biggest barrier to family physical activity (Bellows-Riecken and Rhodes 2008). The barrier of laziness, however, suggests that a more motivational-based rather than regulatory-based intervention may have helped for some participants.

Despite the promising findings of this study, the results should be considered with conservative optimism. Pilot-level work, like this research, is needed given the low performance of prior physical activity trials among youth and intergenerational promotion efforts. It stands to reason that initial positive findings should now be followed-up with a larger trial. The present study had a short-term design of 4 weeks; expanding the trial to a much longer duration would be helpful to establish whether parents can maintain their regulatory skills for family activity. The veracity (e.g., reliability, validity, bias to social desirability) of our self-report measure should also be established using objective means of measuring both parent and child activity such as accelerometry. This would allow for an assessment of intensity, which was not viable with our collective measure of physical activity. Still, the self-report measure used in this study should have obscured possible effects rather than inflate our significant findings. Adult self-reported physical activity contains random measurement error (Prince et al. 2008) which in theory should attenuate findings; furthermore there is no rationale for why self-reported bias of physical activity would be different between the two groups (Hillsdon et al. 2005).The results also need to be interpreted in terms of study attrition and our sampling frame. ITT analyses maintained the intervention effect for unstructured/informal family physical activity, but it was notable that less active people were more likely to drop-out. In terms of sample generalizability to the sampling frame, our sample matched ethnicity, income, and occupational demographics well (Statistics Canada 2007) but our sample reported a higher level of education. This may have had an impact on the efficacy of the planning intervention as these types of interventions have shown better success with educated populations (Gollwitzer and Sheeran 2006).

In summary, the purpose of this study was to examine the short-term effect of a planning intervention in comparison to a standard condition on intergenerational physical activity in families with young children. The planning intervention resulted in higher self-reported family physical activity compared to the standard condition and this was due to an increase in unstructured family activities over the 4 weeks. Intention and perceived control over family physical activity, however, did not change and were not different between groups. The results are promising and suggest that theoretical fidelity targeting parent regulation of family activity may be a helpful approach to increasing weekly energy expenditure. Future larger-scale trials emphasizing this approach are now needed to test the veracity of these findings.

References

Ajzen, I. (2002). Construction of a theory of planned behavior intervention. Retrieved April 4, 2007, from http://www-unix.oit.umass.edu/~aizen/pdf/tpb.intervention.pdf.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). Theory-based behavior change interventions: Comments on Hobbis and Sutton. Journal of Health Psychology, 10, 27–31.

Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education and Behavior, 31, 143–164.

Bellows-Riecken, K. H., & Rhodes, R. E. (2008). The birth of inactivity? A review of physical activity and parenthood. Preventive Medicine, 46, 99–110.

Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. (2004). Increasing physical activity: Trends for planning effective communication. Retrieved February 24, 2006, from http://www.cflri.ca/cflri/resources/pub.php#2003capacity.

CDC. (2001). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey questionnaire. Atlanta. GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

Courneya, K. S., & McAuley, E. (1994). Factors affecting the intention-physical activity relationship: Intention versus expectation and scale correspondence. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 65, 280–285.

Craig, C. L., Marshall, A. L., Sjostrom, M., Bauman, A., Booth, M., Ainsworth, B., et al. (2003). International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(8), 1381–1395.

Dillman, D. A. (1983). Mail and other self-administered questionnaires. In P. H. Rossi, J. D. Wright, & A. B. Anderson (Eds.), Handbook of survey research (pp. 359–378). Toronto, ON: Academic Press.

Dishman, R. K., & Buckworth, J. (1996). Increasing physical activity: A quantitative synthesis. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 28, 706–719.

Fishbein, M., Triandis, H. C., Kanfer, F. H., Becker, M., Middlestadt, S. E., & Eichler, A. (2001). Factors influencing behavior and behavior change. In A. Baum & T. A. Revenson (Eds.), Handbook of health psychology (pp. 3–17). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Godin, G., Jobin, J., & Bouillon, J. (1986). Assessment of leisure time exercise behavior by self-report: A concurrent validity study. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 77, 359–361.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 69–119.

Gustafson, S., & Rhodes, R. E. (2006). Parental correlates of child and early adolescent physical activity: A review. Sports Medicine, 36, 79–97.

Health Canada. (2002). Health Canada’s Physical Activity Guide. Retrieved August, 2004, from http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/english/lifestyles/physical_activity.html.

Hillsdon, M., Foster, C., & Thorogood, M. (2005). Interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.

Kahn, E. B., Ramsey, L. T., Brownson, R. C., Heath, G. W., Howze, E. H., & Powell, K. E. (2002). The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22, 73–107.

Lewis, B. A., Marcus, B., Pate, R. R., & Dunn, A. L. (2002). Psychosocial mediators of physical activity behavior among adults and children. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23(2), 26–35.

Lippke, S., Ziegelmann, J. P., & Schwarzer, R. (2004). Behavioral intentions and action plans promote physical exercise: A longitudinal study with orthopedic rehabilitation patients. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26, 470–483.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

McIntyre, C. A., & Rhodes, R. E. (2009). Correlates of physical activity during the transition to motherhood. Women and Health, 49, 66–83.

Milne, S., Orbell, S., & Sheeran, P. (2002). Combining motivational and volitional interventions to promote exercise participation: Protection motivation theory and implementation intentions. British Journal of Health Psychology, 7, 163–184.

Noar, S. M., & Zimmerman, R. S. (2005). Health behavior theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: are we moving in the right direction? Health Education Research, 20, 275–290.

Norman, P., & Conner, M. (2005). The Theory of Planned Behavior and Exercise: Evidence for the Mediating and Moderating Roles of Planning on Intention-Behavior Relationships. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 27, 488–504.

O’Connor, T. M., Jago, R., & Baranowski, T. (2009). Engaging parents to increase youth physical activity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventitive Medicine, 37, 141–149.

Prestwich, A., Lawton, R., & Conner, M. (2003). The use of implementation intentions and the decision balance sheet in promoting exercise behaviour. Psychology and Health, 18, 707–721.

Prince, S. A., Adamo, K. B., Hamel, M. E., Hardt, J., Connor Gorber, S., & Tremblay, M. (2008). A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5, doi:10.1186/1479-5868-1185-1156.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2002). Canada’s family guide to physical activity (6–9 years of age) [Electronic Version]. Retrieved June 10, 2009 from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/pau-uap/paguide/child_youth/pdf/kids_family_guide_e.pdf.

Rhodes, R. E., Blanchard, C. M., Matheson, D. H., & Coble, J. (2006a). Disentangling motivation, intention, and planning in the physical activity domain. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7, 15–27.

Rhodes, R. E., Brown, S. G., & McIntyre, C. A. (2006b). Integrating the perceived neighbourhood environment and the theory of planned behaviour when predicting walking in Canadian adult sample. American Journal of Health Promotion, 21, 110–118.

Rhodes, R. E., & Courneya, K. S. (2003). Self-efficacy, controllability, and intention in the theory of planned behavior: Measurement redundancy or causal independence? Psychology and Health, 18, 79–91.

Rhodes, R. E., & Courneya, K. S. (2004). Differentiating motivation and control in the theory of planned behavior. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 9, 205–215.

Rhodes, R. E., Courneya, K. S., Blanchard, C. M., & Plotnikoff, R. C. (2007). Prediction of leisure-time walking: An integration of social cognitive, perceived environmental, and personality factors. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 4, 51.

Rhodes, R. E., Courneya, K. S., & Jones, L. W. (2003). Translating exercise intentions into behavior: Personality and social cognitive correlates. Journal of Health Psychology, 8, 447–458.

Rhodes, R. E., & Pfaeffli, L. A. (2009). Mediators of physical activity behaviour change among adult non-clinical populations: A review update. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37, s85.

Rhodes, R. E., & Plotnikoff, R. C. (2006). Understanding action control: Predicting physical activity intention-behavior profiles across six months in a Canadian sample. Health Psychology, 25, 292–299.

Rhodes, R. E., Plotnikoff, R. C., & Courneya, K. S. (2008a). Predicting the physical activity intention-behaviour profiles of adopters and maintainers using three social cognition models. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 36, 244–252.

Rhodes, R. E., Symons Downs, D., & Bellows Riecken, K. H. (2008b). Delivering inactivity: A review of physical activity and the transition to motherhood. In L. T. Allerton & G. P. Rutherfode (Eds.), Exercise and women’s health research (pp. 105–127). Hauppauge, NY: Earthlink Science Press.

Sniehotta, F. F., Scholz, U., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). Bridging the intention-behaviour gap: Planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychology and Health, 20, 143–160.

Sniehotta, F. F., Scholz, U., & Schwarzer, R. (2006). Action plans and coping plans for physical exercise: A longitudinal intervention study in cardiac rehabilitation. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 23–37.

Statistics Canada. (2007). 2006 Census. Retrieved September 24, 2007, from http://www.statcan.ca/start.html.

Strecher, V. J., Seijts, G. H., Kok, G. J., Latham, G. P., Glasgow, R., DeVellis, B., et al. (1995). Goal setting as a strategy for health behaviour change. Health Education Quarterly, 22(2), 190–200.

Temple, V. A., Naylor, P. J., Rhodes, R. E., & Wharf-Higgins, S. J. (2009). Physical activity of Canadian children in family child care. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism (in press).

Van Sluijs, E. M. F., McMinn, A. M., & Griffin, S. J. (2007). Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: Systematic review of controlled trials. British Medical Journal, 335, 703.

Warburton, D. E. R., Katzmarzyk, P., Rhodes, R. E., & Shephard, R. J. (2007). Evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for Canadian adults. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism, 32, S16–S68.

World Health Organization. (2008). Physical inactivity: A global public health problem [Electronic Version]. Retrieved June 5, 2009 from http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_inactivity/en/index.html.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP) from the British Columbia Ministry of Family. RER was also supported by Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and Canadian Institutes for Health Research salary support awards during the tenure of this research. We acknowledge and thank Naomi Casiro and Thalia Parkinson for the hard work of data collection and entry on this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rhodes, R.E., Naylor, PJ. & McKay, H.A. Pilot study of a family physical activity planning intervention among parents and their children. J Behav Med 33, 91–100 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-009-9237-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-009-9237-0