Abstract

Diabetes is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and it is now cited along with obesity as a global epidemic. Significant racial/ethnic disparities exist in the prevalence of diabetes within the US, with racial and ethnic minorities disproportionately affected by type 2 diabetes and its complications. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic factors influence the development and course of diabetes at multiple levels, including genetic, individual, familial, community and national. From an ecodevelopmental perspective, cultural variables assessed at one level (e.g., family level dietary practices) may interact with other types of variables examined at other levels (e.g., the availability of healthy foods within a low-income neighborhood), thus prompting the need for a clear analysis of these systemic relationships as they may increase risks for disease. Therefore, the need exists for models that aid in “mapping out” these relationships. A more explicit conceptualization of such multi-level relationships would aid in the design of culturally relevant interventions that aim to maximize effectiveness when applied with Latinos and other racial/ethnic minority groups. This paper presents an expanded ecodevelopmental model intended to serve as a tool to aid in the design of multi-level diabetes prevention interventions for application with racial/ethnic minority populations. This discussion focuses primarily on risk factors and prevention intervention in Latino populations, although with implications for other racial/ethnic minority populations that are also at high risk for type 2 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Systems models and the determinants of health

Health disparities involving chronic degenerative diseases

The Healthy People 2010 guidelines emphasize two overarching goals for improving the nation’s health: (1) to increase quality and years of healthy life, and (2) to eliminate health disparities (US Department of Health, Human Services 2000). This second goal refers to group differences in the burden of mortality and morbidity that are distributed inequitably by: “gender, race or ethnicity, education, income, disability, geographic location and/or sexual orientation,” (US Department of Health, Human Services 2000, p. 11). From a comprehensive public health perspective, coordinated interventions presented at two or more ecological levels are now needed to produce population-wide, comprehensive, and efficacious reductions in any given health disparity, such as the disproportionately higher rates of type 2 diabetes among racial/ethnic minority groups (Institute of Medicine. 2003; Liburd et al. 2005). Such interventions can range from the macrolevel (e.g., changing social policy, social institutions, cultural norms and practices) to the microlevel (e.g., family-oriented and individualized diabetes prevention interventions) (Jones 2006). Towards this aim, the current article introduces an expanded ecodevelopmental model (Pantin et al. 2004; Szapocznik and Coatsworth 1999) as a tool for the conceptualization, planning and design of prevention interventions to change dietary and physical activities that can avoid or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A related goal is to aid in the conceptualization and design of culturally sensitive diabetes prevention interventions that are tailored to the particular needs of a specific racial/ethnic minority population (Kumpfer et al. 2002). Although this discussion will focus primarily on Latinos, a group at high risk for the development of type 2 diabetes, these models are intended for application with various groups.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Diabetes is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States (Moskowitz et al. 2008) and it is now cited along with obesity as a global epidemic (Collagiuri et al. 2006). Racial/ethnic populations in the US are disproportionately affected by type 2 diabetes and its complications. As compared with non-Hispanic Whites who exhibit age-adjusted rates of diabetes of 6.4%, age-adjusted rates are comparatively higher in the three major racial/ethnic groups, and these rates are: American Indians and Alaska natives (15.0%), African-Americans (11.5%), and Hispanics (10.1%) (Barnes et al. 2008) (see Table 1).

Modifiable personal risk factors for the development of type 2 diabetes include: obesity and low levels of physical activity as well as environmental factors such as impoverished neighborhoods. These factors contribute directly or indirectly to the risk of diabetes, and may also affect gene expression, thus further modifying the risks for this disorder (Dagogo-Jack 2003). Among these major risk factors, obesity is a consequence of an imbalance in the consumption of calories from metabolic fuels (carbohydrates, fats and proteins) relative to their expenditure, resulting in the net accumulation of unexpended metabolic fuels as adipose tissue. Physical inactivity also directly and indirectly affects diabetes risk. Clinical studies have shown that exercise enhances skeletal muscle glucose uptake and improves insulin resistance (Ivy 1997). These exercise effects are the result of a coordinated up-regulation of several components in the insulin signaling cascade which facilitate the incorporation of glucose into skeletal muscle (Zierath 2002). Individuals who participate in regular physical activity exhibit a reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes (Wei et al. 1999). Indirectly, physical activity affects risk through its effects on weight regulation.

In a major multi-site randomized controlled trial of 3,234 pre-diabetic adults conducted by the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, treatment with the medication metformin, and lifestyle modification were both efficacious interventions for delaying or preventing type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group 2002). These investigators indicate that, “the lifestyle intervention was particularly effective,” indicating the effect of, “one case of diabetes prevented per seven persons treated for 3 years,” (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, p. 401). However, it is noteworthy that the efficacy of this lifestyle intervention was a consequence of an intensive regimen with the goals of reducing at least 7% of initial body weight using a low-caloric diet, and increasing physical activity via moderate-intensity brisk walking for at least 150 min per week. In addition, these lifestyle changes were guided by a 16-lesson curriculum that was supervised by a case manager who provided monthly support sessions that were described as: individualized, flexible and culturally sensitive.

The current challenge of replicating this prevention intervention program with underserved populations involves establishing the setting conditions, the program infrastructure and staffing that would facilitate and sustain this level of intense lifestyle change for the requisite period of time. Communities low in socioeconomic status lack the requisite resources and community organization necessary to develop such diabetes prevention programs, yet many of these same communities are those with the highest rates of type 2 diabetes, thus having the greatest needs for such programs. Accordingly, a major public health challenge for many ethnic and underserved communities involves the acquisition of resources and the supportive infrastructure to implement such an intensive diabetes prevention intervention program.

Considerations in conceptualizing race and ethnicity

Prior to the examination of the aforementioned systems models, we will review important considerations in the conceptualization of race/ethnicity and culture in the design of prevention interventions. Racial/ethnic factors can influence dietary behaviors and physical activity via multiple pathways that include genetic variations in risk among populations, cultural variations in the practice of self-regulation, familial beliefs and attitudes about diet and exercise and the accompanying dietary practices, community-level differences in risks and in access to resources, and national policies that result in the unequal distribution of access to healthy environments (Collagiuri et al. 2006; Horowitz et al. 2004; Satcher and Higginbotham 2008). Understanding the multifaceted ways in which ethnic factors can affect diabetes risks is key to the development of effective and culturally relevant preventive interventions.

The variables of race and ethnicity are typically measured as categorical person-background variables based on a respondent’s self-classification (US Census 2008a). As one important distinction, the US Census distinguishes “racial” categories from “ethnicity,” i.e., being Hispanic (US Census 2008a; US Census 2008b). However, much variability exists in the conceptualization and measurement of race and ethnicity (Bonham 2005), and scholars have argued that race should not be regarded as a biological construct, although it remains important as a health-related variable when conceptualized as a sociocultural construct (Smedley and Smedley 2005). In many epidemiological studies, race is utilized as a categorical grouping variable for conducting group comparisons, as, e.g., to examine the presence of health-related disparities based on racial/ethnic-group comparisons, i.e., Hispanics, Blacks versus non-Hispanic White Americans. Such group comparisons, however, do not explain the underlying mechanisms that may drive these differences. Furthermore, due to existing within-ethnic-group heterogeneity, this variability must also be measured for any racial/ethnic group, e.g., for Latinos, using a relevant cultural variable such as level of acculturation, while also considering specific national origins. As contrasted with race, ethnicity is a cultural variable that refers to, “a common ancestry through which individuals have evolved shared values and customs. It is deeply rooted to the family through which it is transmitted.” (McGoldrick and Giodano 1996, p. 1). Ethnicity also confers a sense of identity and belonging and a sense of “peoplehood,” and it transmits core systems of cultural beliefs, values, norms traditions and customs, which in turn can also influence health-related behaviors (Harwood 1981).

Approaches and considerations regarding context

Core issues regarding the analysis of contexts

The term context is used often within the health systems literature to acknowledge the situational or environmental “surrounding” conditions that can affect a specific process or outcome. For example, a therapist must consider cultural and familial “surrounding” contexts in planning a culturally relevant family intervention (Chesla et al. 2003). An adolescent obesity prevention intervention may need to be implemented in a different manner within a family system that exhibits high levels of conflict among its members, as contrasted with a family system that exhibits low levels of conflict. Accordingly, an intervention plan that is “out of context,” with ambient surrounding conditions will likely be ineffective. In working with systems, successfully attaining a healthy targeted outcome thus requires a thorough understanding of relevant contextual conditions. Moreover, more complete information regarding the total context that “surrounds” a specific event can temper or even modify the meaning of that event. Thus, examining “surrounding” systemic cultural contexts in adequate detail would contribute to a more complete “deep structure” understanding (a more complete understanding of important underlying factors) (Resnikow et al. 2000) of core systemic effects that govern a targeted health-related outcome. This deeper understanding aids in more accurately interpreting “cultural nuances” (subtle but important aspects) (Castro and Coe 2007), these being subtle but important distinctions regarding a culture’s core features or practices.

Context refers also to conditional effects, meaning that a health outcome is dependent on the particular level of a specific or controlling condition that affects that outcome. Examples of contextual levels include whether a family system consists of a single-parent family or a two parent family (Pan and Farrell 2006), or community environmental features (e.g., impoverished vs. resource-rich) (Wandersman and Nation 1998). Person factors such as gender and level of acculturation can also operate as contextual factors. In a study of family environments, parental body mass index (BMI) was examined as a contextual factor affecting the BMI of adolescents from these families (Kosti et al. 2008). Gender-specific effects were observed and these investigators report that the father’s obesity was a more important determinant of the BMI of the male child, whereas the mother’s obesity was a more important determinant of BMI for the female child.

Thus, contextual variables can include, situations (e.g., low-risk vs. high risk situations), environments (e.g., rural vs. urban neighborhoods, or low-income vs. high income neighborhoods), family system characteristics (e.g., single parent vs. dual-parent family systems), person variables (e.g., gender- male vs. female; or levels of acculturation- low, bicultural, or high) and also temporal factors (e.g., day vs. night, or developmental milestones such as adolescence vs. adulthood). Regarding temporal contexts, a study of workload stressors using the National Survey of Workplace Health and Safety examined drug use among working employees and observed that under a context-free assessment, drug use was unrelated to workload stressors, whereas under a context-specific assessment involving time of day when drugs were consumed (before work, during work, or after work), drug use was associated with workload stressors (Frone 2008). Thus, the time of day when drugs were consumed influenced the observed association between workload stressors and levels of drug use. These considerations regarding context underscore the importance of utilizing a multi-systemic model analysis of relevant contexts, as these can aid in understanding the onset of disease.

Cultural contexts

The aim of designing optimal and culturally relevant diabetes prevention interventions also highlights the importance of conceptual clarity and rigor in the analysis of cultural effects that may influence health-related outcomes such as the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Under a more rigorous approach, a complex multi-faceted construct such as “culture” is best deconstructed, that is, broken down into more specific and measurable cultural variables, whose specific influences on health outcomes can then be explicitly hypothesized and tested within specific structural models (Castro and Hernández-Alarcón 2002). Such discrete cultural variables include: level of acculturation, familism, and traditionalism, as their effects can be examined as influences on health-related outcomes such as type 2 diabetes. As one example, within a Latino community, higher level of acculturation as measured by years living within the US or by generational status (foreign born, first generation US born, second generation US born) was associated with higher levels of BMI. Persons who were obese (BMI > 30) relative to those not obese, were 1.6 times more likely to be second generation residents, (i.e., of higher level of acculturation) (Herbert et al. 2005). In this instance, level of acculturation may be conceptualized as a context-setting moderator variable whose various levels (low acculturated, bicultural, high acculturated) may differentially influence dietary practices, such as acculturation-level differences in the consumption of calories or fatty foods (Herbert et al. 2005; Sternet al. 1991).

In the following section we will examine models that can guide a systemic conceptualization of precursor and contextual factors, including cultural variables, as influences on health-related outcomes such as type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Systems models: the biopsychosocial and ecodevelopmental models

Background on general systems models

A major challenge in the prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in racial/ethnic minority populations involves the development of a more complete multi-level and systemic conceptualization of disease etiology that can guide the design and implementation of more comprehensive, efficacious, empirically and culturally grounded diabetes prevention interventions. These interventions would best recognize the multiple contexts that affect diabetes etiology and its onset especially among diverse racial/ethnic minority populations (Liburd et al. 2005). Reductionistic conceptualizations and paradigms regarding the pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus, while very useful, also often exclude the effects of the sociocultural determinants of disease, thus limiting their potential for reducing health disparities (Castro et al. 2008; Schulz et al. 2005). It is important to understand individual behavior within its sociocultural context, given that personal lifestyle behaviors including nutritional habits, physical activity, and stress-coping responses account for over 40% of the variance in health outcomes (Satcher and Higginbotham 2008).

Prior systemic models

In 1977, George L. Engel proposed the biopsychosocial model as a viable alternative systems framework to the conventional biomedical model. The biopsychosocial model emphasizes the interactive influences of multiple and interdependent systemic domains (Engel 1977). In parallel with Engel’s conceptualizations, Uri Bronfenbrenner (1986) regarded family systems as fundamental units of child development. This systemic approach is also applicable to studies of somatic health. From a different perspective, Social Cognitive Theory has introduced a systemic approach that emphasizes “reciprocal determinism,” as an interactive process that involves three factors: the environment, behavior, and the person (Bandura 1986), although this approach does not address the influence of organic factors. Clearly, each of the aforementioned models offers a foundation for multi-systems analyses, although they also present limitations to a more comprehensive multi-level and systemic analysis of the determinants of health and disease.

An ecodevelopmental model

In a contemporary elaboration of Bronfenbrenner’s systems model, several investigators have recently described an ecodevelopmental model (Pantin et al. 2004; Szapocznik and Coatsworth 1999) that examines a hierarchy of systems. As described by Pantin and colleagues, the highest order domain is macrosystems- broad social and philosophical ideals and sociocultural influences, e.g., American (North American) cultural norms (Locke 1998; Pantin et al. 2004). A lower-level ecological domain is the exosystems. As defined by Bronfenbrenner, systems within the ecosystems domain do not directly affect the individual person, although they are said to exert indirect effects through other individuals or processes (Bronfenbrenner 1986; Pantin et al. 2004). A still lower-level ecological domain is: (3) mesosystems- systemic factors that are said to directly affect the individual person, such as family supports, familial food and exercise preferences, and among immigrant families, the process of “differential acculturation” that occurs between immigrant parents and their children (Pantin et al. 2004). In this rendition of the ecodevelopmental model, the lowest-level domain is the: (4) microsystems- personal and familial factors and situations in which the person participates directly (Pantin et al. 2004). These systemic models offer a broad-based analysis of systemic influences, but are nonetheless classifiable only as “descriptive models,” because they describe but do not specify the nature and directionality of the effects that one system has on another.

Model specificity and utility for scientific research

In contrast to earlier descriptive models, whose primary function was to “describe and illustrate,” types of models classifiable as “schematic models,” offer a more explicit analysis of the direction of effects occurring among model components. For example, one model has shown how minority status or cultural identity may influence specific health-related outcomes (Schulz et al. 2005), such as survival or quality of life (Meyerowitz et al. 1998). Beyond schematic models, “measurement/structural models,” such as structural equation models (Byrne 2006), hierarchical linear models (Kreft and De Leeuw 1998; Raudenbush and Byrk 2002), or latent growth models (Bollen and Curran 2006) introduce further improvements because they allow the operationalization, measurement and testing of relationships among model components. As full measurement models, structural models thus allow direct tests of model hypotheses based on empirically generated data. For example, as related more specifically to risks for type 2 diabetes, a multi-level analysis of changes in body mass index (BMI) can be examined by analyzing group differences in BMI growth curves (e.g., between Latinos and non-Hispanic whites) that occur from adolescence to adulthood (Heo et al. 2004).

An expanded and modified ecodevelopmental model

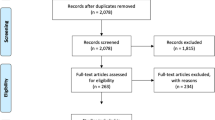

Several challenges thus exist regarding the operationalization of the ecodevelopmental model and its variants for scientific hypothesis testing in studies of health-related outcomes. As originally conceptualized by Bronfenbrenner (1986), the unit of analysis is a “set of systems,” although as originally defined, this is a complex construct which is difficult to operationalize. A re-framing of this model in terms of identifying more discrete components or factors that exist within a given systemic domain will allow the explicit operationalization and specification of the hypothesized effects of one model component on another. Such effects can be hypothesized to occur across levels (domains), across points in time (stability or developmental effects), as well as in cross-lagged effects that can occur both across domains and points in time. Figure 1 presents a “concentric circle” ecodevelopmental model that has been adapted from a prior model by Pantin et al. (2004), and as casted here for the analysis of factors affecting the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. This concentric-circle model illustrates how a higher-order domain, e.g., Familial Systems, introduces “surrounding” contexts that influence events occurring at the lower level of Individual Systems. In turn, the domain of Community Systems also introduces “surrounding” contexts that affect the lower level of Family Systems, etc. Furthermore, Fig. 2 presents a multi-level “temporal” ecodevelopmental model that introduces a temporal gradient to facilitate the analysis of effects that can occur across specific life milestones.

A “concentric circle” ecodevelopmental model of factors affecting type 2 diabetes. This figure is modified from a prior figure that illustrates Bronfenbrenner’s ecodevelopmental model as described by Pantin et al. (2004)

Within the “concentric circle” ecodevelopmental model as shown in Fig. 1, when moving from the lowest-level domain to the highest, one can define this system of domains in the following manner. First, organic-level factors (domain 1) consist of the smallest (“nano-level”) elements that exist “within the person,” i.e., organs, cells, genes and molecules (see Fig. 1). Second, individual-level factors (domain 2) “the person,” consist of psychological factors that include: (a) cognitions (beliefs, attitudes, values, expectations, perceptions), (b) arousal and affect (positive emotions such as happiness or hope; and negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger, or paranoia), and (c) behaviors (individual dietary and physical activity behaviors). Within this individual domain, level of acculturation can be regarded as a cultural factor that involves a person’s acquisition of language, knowledge, attitudes, skills, behaviors, values and other aspects of daily living as necessary for social function within a new cultural environment (Portes and Rumbaut 1996). Acculturation change/cultural adaptation may thus involve changes across time in dietary and other health behaviors, some of which may increase risks for diabetes, both directly through changes in diet and exercise, but also indirectly, as, e.g., in changes that increase stress reactivity, although not all aspects of cultural adaptation are necessarily stressful (Berry 2005; Castro 2007).

Third, familial-level factors (domain 3- micro and meso-level factors) consist of relationship patterns that range from a dyad (husband-and-wife) to extended family systems (children, close kin, familial food preferences, familial physical activity and exercise habits). Fourth, community-level factors (domain 4) consist of geographically contiguous elements such as neighborhood entities (e.g., neighborhood grocery stores and restaurants), although communities can also be non-contiguous geographically, such as in Internet communities. Environmental features of these community-level factors can include, e.g., the rural-urban aspects of a community.

Fifth, sociocultural-level factors (domain 5) consist of macro-level social institutions, such as regional or national cultural values or norms, and may include discriminatory social policies or institutions whose adverse “top–down” effects on communities, families or individuals may differ by ethnicity, social class, immigration status and other contextual variables. For example, racially discriminatory social policies can be conceptualized as sociocultural-level events that disproportionately and adversely affect certain racial/ethnic minority families and individuals (Clark et al. 1999).

Multi-level interactions

Multi-level interactions among these systems can be depicted as circles that overlap two domains (see Fig. 1). For example, events that involve the individual (domain 2) and the community (domain 4) can be described as “individual-community interactions” (2, 4). For example, limitations in the built environment such as the absence of heart healthy foods within local grocery stores, or a lack of neighborhood recreational areas such as parks, can interact with individual perceptions that the neighborhood is unsafe for doing exercise and is devoid of healthy foods. These environmental-perceptual factors may thus contribute jointly to a low frequency of healthy eating and to low levels of physical activity occurring among these community residents. Similarly, “individual-sociocultural interactions” (2, 5) may involve social-level acculturation stressors, such as aggressive law enforcement policies levied against certain Latinos, and at the person level, fears of deportation, where this interactive process would also discourage doing physical activities and exercise within the local neighborhood.

Multi-level effects

Based on this expanded ecodevelopmental model as applied to type 2 diabetes, Fig. 2 presents a “temporal” ecodevelopmental model that features time effects that can be examined across five lifecycle milestones: birth, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age. Similar life course models have been proposed elsewhere that describe stages within human developmental trajectories (Horsley and Ciske 2005). The present “temporal” ecodevelopmental model illustrates that during adolescence, organic (nano-level) events can be influenced by individual (micro-level) behaviors, and vice versa (bi-directional path a). Organic factors can also be influenced by community-level factors (e.g., the limited availability of nutritious foods within local neighborhood grocery stores) (uni-directional path b). Furthermore, the effects of familial-level factors, e.g., familial habits that involve eating large meal portions and high fat foods, as well as low levels of physical activity, can be modeled as influences on organic-level factors, e.g., increases in fat cell size and numbers and subsequent weight gain or obesity (uni-directional path c), which in turn may operate as precursors of insulin resistance and the subsequent onset of type 2 diabetes.

Temporal and interactive effects

Other interactive effects can also be modeled as these can occur temporally across specific milestones in the lifecycle (see Fig. 2). For example, regarding the onset of type 2 diabetes during adolescence, the effects of organic diabetes risk conditions originating at birth (e.g., family history of diabetes or mother’s gestational diabetes during pregnancy) (uni-directional path d) and childhood individual eating habits (uni-directional path e) can exert a synergistic effect in promoting obesity and can thus be modeled as jointly contributing precursors to diabetes onset as this would occur during adolescence. In other words, for the “Individual level” and occurring at the “Adolescent milestone,” the onset of type 2 diabetes can be depicted as a consequence of temporal influences from two earlier-life stage events as indicated by paths d and e.

Similarly, multi-level influences that occur during adolescence and that involve sociocultural, familial, and organic effects can be modeled as precursors of the onset of type 2 diabetes at the “Adulthood milestone.” For example, among immigrant Latino adolescents, acculturation stressors may involve discriminatory barriers encountered during unsuccessful efforts to “fit in” with the white dominant-culture. This experience can be modeled as a sociocultural effect that affects the individual youth (uni-directional path f). Similarly, originating at the “Familial-level” and the “Adolescence milestone,” acculturation stressors involving parent-child conflicts produced by differing rates of parent-child acculturative change can influence an “Individual-level” outcome that occurs at the “Adulthood milestone” (uni-directional path g) (Farver et al. 2002). Multiple effects that contribute to the onset of type 2 diabetes observed at the “Individual-level” and diagnosed at the “Adult milestone,” can consist of organic-level influences that begin at the “Adolescence milestone,” and that involve increases in the size and number of fat cells consistent with obesity (uni-dimensional path h), along with the aforementioned effects of acculturation stressors (path f), which may then operate as joint multi-level influences that affect the onset of type 2 diabetes as diagnosed during adulthood (see Fig. 2). Thus, within a longitudinal study, each of these hypothesized effects, if operationalized and measured at the noted time points, could then be tested empirically for their respective and joint influences as significant precursors of type 2 diabetes occurring in adulthood. Moreover, for a given cohort, secular effects can also be modeled as events that occur across time and solely within a specific domain, (e.g., within the Community domain and across several life milestones, or within the Sociocultural domain, across time as these events may operate as macro-level precursors of population-level prevalence rates of type 2 diabetes).

Contextual effects

As noted previously, the analysis of context recognizes that disease outcomes are often determined not only by the direct effect of one or more precursor factors, but also by ambient environmental “surrounding” conditions that constitute contextual factors that produce “effect modification” (i.e., operate as moderators), such as the moderating effects of gender norms on risks of certain diseases that differ by gender, e.g., depression. Within this ecodevelopmental model, the race/ethnicity factor, e.g., identity as a Pima Indian, when conceptualized as an organic-domain factor (path i), can be modeled as a genetically inherited moderator and risk factor for type 2 diabetes risk as this influences the Birth-to-Childhood trajectory and beyond (see Fig. 2). For example, being born into a high-risk indigenous racial/ethnic family group (e.g., the Pima Indian tribe of Arizona; the Salt River Indian community), relative to being born into a white non-Hispanic racial/ethnic family, may operate as a moderator effect wherein from early life that child exhibits a high-risk life trajectory for the onset of type 2 diabetes (Gardner et al. 1984; Lillioja et al. 1988), although the actual onset and expression of diabetes will be determined also by environmental, behavioral and other co-occurring factors.

In this regard, among Pima Indian tribes that live on the US Arizona and Mexico sides of the US-Mexico border, differing rates of type 2 diabetes have been observed. In a study of traditional indigenous and Westernized lifestyles as related to prevalence rates of type 2 diabetes, Shulz et al. (2006) found lower prevalence rates of type 2 diabetes in the Pima Indians of Mexico, as compared with the Pima Indians of the US. Also, levels of physical activity were much higher in the Mexican Pimas relative to the US Pimas. These two communities share considerable genetic similarities, yet differences in community environments (“surrounding” contextual conditions) and in lifestyle behaviors appeared to be associated with these differing rates of type 2 diabetes. Thus, these investigators assert that despite genetic propensities to develop diabetes, based on having similar genetic features, type 2 diabetes is preventable via environmental and behavioral influences that are consistent with risk reduction for diabetes.

Evidence regarding ecodevelopmental approaches to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Domain-related effects on type 2 diabetes

In the following sections we will examine evidence supporting the role of factors at each systemic level (domain) (i.e., nano, individual, familial, etc.) that can affect the onset and course of diabetes or diabetes risks. This discussion will address two critical approaches in the use of this ecodevelopmental model for understanding processes affecting the development of type 2 diabetes. First we illustrate that the onset of type 2 diabetes is multiply determined, that is, a consequence of multiple risk factors–genetic, individual and environmental—and that the influence of these risk factors involves interactions that occur among them. Second, we consider how ethnicity may operate as a moderator variable, that is, as an effect modifier.

Nano or organic-level factors affecting type 2 diabetes

Mechanisms of insulin action

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a disease of metabolic energy imbalance (i.e., obesity) resulting in ineffective mechanisms of insulin action including the presence of insulin resistance. Type 2 diabetes is characterized by elevated plasma glucose levels secondary to defects in insulin action and secretion (Weyer et al. 1999). According to the 1997 criteria established by the American Diabetes Association, type 2 diabetes mellitus is indicated by a fasting blood glucose value of 126 mg per deciliter or higher, or a blood glucose value of 200 mg per deciliter or higher two hours after a 75 g oral glucose load (American Diabetes Association 2008).

Insulin has two primary functions related to glucose metabolism; it facilitates glucose transport into skeletal muscle cells and it inhibits glucose production by the liver (Guyton 1981). As individuals become insulin resistant, the amount of insulin required to maintain glucose homeostasis is increased (Haffner et al. 1986). This increased demand for insulin is met by the pancreatic beta cells which endogenously produce and secrete insulin. However, in certain individuals and within some ethnic groups, the β-cells cannot keep pace with an increasing level of insulin resistance and the ensuing β-cell insufficiency results in elevated blood glucose levels which typify type 2 diabetes (Ferrannini et al. 2005). It remains unclear, however, which genetic and other factors determine an individual’s susceptibility for β-cell failure, although a family history of type 2 diabetes is a marker for this susceptibility, suggesting a strong hereditary component to this disorder (Jensen et al. 2005).

Ethnic differences in insulin resistance

Evidence has accrued to suggest that individuals of African American and Latino descent are more insulin resistant than non-Hispanic whites (Albu et al. 2005; Goran et al. 2002). These ethnicity-related differences have treatment implications. The molecular response to one level of intervention, (e.g., exercise) may be modulated by the degree of insulin resistance whereby a less robust response is observed in insulin-resistant populations (De Filippis et al. 2008). An extrapolation of these findings suggests that more insulin resistant groups may fail to show the expected salutary effect of exercise on outcome markers (e.g., blood glucose levels), and they therefore may require a greater exercise stimulus or dose to attain similar protective effects against the onset of type 2 diabetes.

Individual-level factors affecting diabetes

The role of psychological factors, including cognitions, affect, and behavior, has been examined in the onset, self-management and regulation of diabetes. Hovell et al. (2008) report on common misperceptions about diet and exercise that exist among some low-income Latinas. For example, there are common misperceptions (or miscalculations) about the degree to which exercise offsets caloric intake. Such inaccurate cultural perceptions may work synergistically with biological processes in contributing to the onset of diabetes (Arcury et al. 2004).

Moskowitz et al. (2008) also report that negative affect (anxiety, depression, anger) is associated with a greater likelihood of having diabetes. An important issue in such studies involves the relative strength of cognitive and affective “person factors,” as contrasted with genetic and environmental factors, as precursors, whether direct or indirect, in the development of type 2 diabetes. There may also exist ethnicity-related differences in stress exposure, coping skills and emotional expression that can influence the expression of diabetes-related generic processes.

Ethnicity may also influence health-related behaviors, which include individual-level (person factors) that can promote diabetes risks or diabetes prevention. Specifically, ethnicity may be associated with variations in the practice of a healthy and balanced lifestyle, one that features a series of behaviors that include: healthy dietary practices (the consumption of low fat foods and low caloric diets), physical activity (aerobic, muscle building, flexibility exercises), weight management, stress management, guidance and social support as well as sustained motivation to attain and maintain a healthy lifestyle (Pagoto et al. 2008; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group 2002).

Relative to non-Hispanic whites who exhibit an age-adjusted rate for physical inactivity of 34.8%, the three racial/ethnic minority populations exhibit higher rates: Hispanics (53.6%), African Americans (50.4%), and American Indians and Alaska Natives (41.3%) (Barnes et al. 2008) (see Table 1). Other sociocultural-level factors may further moderate the effects of individual level variables on physical activity. In a study of Mexican-origin community residents, Crespo and collaborators observed that the prevalence of physical inactivity was inversely related to levels of linguistic acculturation. Relative to those who spoke mostly English (those high in linguistic acculturation), and to those who were bilingual (mid-level acculturation), Mexican-origin community residents who spoke mainly Spanish (those lowest in linguistic acculturation) exhibited the highest prevalence rates of leisure time physical inactivity (Crespo et al. 2000). Similarly, individual-level factors observed as barriers to physical activity included: a lack of time, feeling too tired, misperceptions about getting sufficient exercise on the job, and a lack of motivation to exercise. These barriers to exercise and physical activity may be a consequence of an interaction between socioeconomic status and a specific aspect of ethnicity, as in the case of lower SES Latino immigrants who work long hours in two or more physically-demanding jobs, and thus are too exhausted to exercise during their limited leisure time.

Ethnic factors associated with treatment compliance can also affect the outcome of individual-level efforts in reducing diabetes risks. Ethnic and regional differences have been identified in the practice of self-regulation to promote exercise adherence. One study examined self-management behaviors among Latinos (mostly Mexicans and Mexican Americans) who have type 2 diabetes and who resided within a rural community in eastern Washington (Coronado et al. 2007). When compared with white non-Hispanics, these Latino residents were less likely to treat their diabetes with diet and exercise, and they were also less likely to engage in self-management practices, including, e.g., planning for exercise and making alternative arrangements to overcome barriers to exercise. Among certain Latinos, low-literacy levels and low knowledge and skills for practicing self-monitoring may contribute to the comparatively lower rates of self-management behaviors observed among these Latinos.

Familial-level factors affecting diabetes

Energy imbalance precursors of type 2 diabetes include familial food preferences or habits involving the consumption of high-fat and energy-rich foods, large food portions, and familial habits involving physical inactivity. Conversely, a family history of diabetes may affect awareness and motivation to self-regulate behaviors that influence the risks of developing type 2 diabetes (Baptiste-Roberts et al. 2007).

Regarding dietary practices, among traditional Latinos and likely among other traditional ethnic minority families, traditional ethnic fiestas and family celebrations often include the consumption of traditional ethnic foods, some of which are high in fat and calories. In a health promotion study, “Promoviendo Estilos de Salud Saludables” (Promoting Healthy Lifestyles), Latino family celebrations were reported to be occasions that impose social pressures to overeat. Such social pressures may be augmented by Latino social norms, such as the cultural expectation of simpatia, which proscribes a deferent compliance to others’ wishes in efforts to maintain harmonious interpersonal relationships. As an illustrative response, one Latina stated, “when someone offers us something to eat, to be polite we don’t refuse… we do that to be courteous or for the sake of our friendship” (Thorton et al. 2006, p. 100). This deference occurs within other cultural groups, although ethnic variations in the expression of simpatia may involve differences in the degree to which such deferential behaviors are proscribed, expected or emphasized as culturally appropriate and as strict normative expectations.

Familial factors can influence the outcome of prevention interventions that are designed to decrease disease risks. A qualitative study of Latinas examined family and social supports as influences on dietary and physical activities, with the aim of reducing risks for obesity and type 2 diabetes (Thorton et al. 2006). For these Latinas, barriers to physical activity included the absence of female relatives and friends who could provide child care, as well as the absence of companionship and other forms of social support. Especially among low-income and recently immigrated Latinas (low acculturated Latinas), community-based family-oriented interventions were identified as social support resources that can promote and sustain healthy lifestyles. Certain familial norms and expectations can thus serve as factors that encourage or discourage certain health-related behaviors, e.g., customs or proscribed cultural norms for eating certain foods, and these can in turn influence diabetes-related risks.

Community-level factors affecting diabetes

Promoting diabetes prevention at the family level must take into account the contextual community factors that “surround” a family system. A limited access to resources can be a critical factor that compromises a family’s ability to engage in diabetes prevention strategies. For example, the absence of healthy food options at local neighborhood grocery stores significantly limits the choices families have for purchasing and preparing nutritious meals. Also, inequities in environmental supports for physical activity can impose community-level barriers and can contribute to health disparities including the disparate rates of diabetes among various US populations (Popkinet al. 2005). Community-level predictors of greater physical activity have included: the presence of sidewalks, enjoyable scenery, and low levels of traffic (Brownson et al. 2001).

A recent study that compared the availability of foods recommended for diabetics within a predominantly African American neighborhood in East Harlem as contrasted with a predominantly Caucasian neighborhood on the Upper East Side of New York found that Upper East Side stores were 3.2 times more likely to stock food products that are appropriate for individuals with diabetes (e.g., fat-free milk, high-fiber bread, and fresh green vegetables) (Horowitz et al. 2004). These findings are even more striking when diabetes rates between these two neighborhoods were also examined. East Harlem has the highest prevalence of diabetes in New York City (15%), whereas the Upper East Side has the lowest prevalence rate (2%) (Thorpe et al. 2003).

Along with access to healthy food options, the built environment may significantly impact an individual’s diabetes risks and contribute to extant health disparities among ethnic minority people who live within these communities. In a recent prospective study of 644 non-diabetic African Americans, impoverished neighborhood or housing conditions increased the risks of developing diabetes over a 3 year period, with odds ratios ranging from 1.78 to 2.53 (Schootman et al. 2007). Specific factors contributing to these effects were not examined in this study, and could serve as the focus of future research. Among Latinos, limited available exercise facilities as well as a lack of culturally relevant diabetes education programs have been identified as factors that predict lower rates of participation in special diets and physical activity, where within one rural community these rates were 16% for Latinos as compared with 50% for non-Hispanic Whites (Coronado et al. 2007).

Sociocultural-level factors affecting diabetes

Policy development often involves a consideration of competing values and of economic and political interests, as these influence decisions regarding the allocation of resources and interventions to resolve a given public health problem (Joffee and Mindell 2006). Obesity in earlier life is a well established risk factor for the onset of type 2 diabetes in later life. “Surrounding” sociocultural-level contextual factors that promote obesity include health-compromising social policies and media marketing messages that encourage the consumption of large food proportions, foods low in nutrition and high in fat, and the consumption of simple carbohydrates, especially as these messages target low-income racial/ethnic minority populations. By contrast, pro-health social policies can contribute to establishing the social and physical environments and their contexts that help to “achieve widespread reductions in both the incidence and prevalence of diabetes,” (Collagiuri et al. 2006, p. 1562).

Changes in social policy that can promote physical activity are particularly important for racial/ethnic minority communities given the many “surrounding” macro-level factors that have created existing health disparities (Jones 2006; Plascia et al. 2008). Nationally supported programs have been developed to promote healthy lifestyles among children. For example, the Action for Healthy Kids program was designed to promote nutrition and fitness via mobilization of volunteers, school boards, and various community organizations to promote obesity reduction among youths in grades K–12. This effort included low SES children whose families were unable to provide guidance for developing healthy lifestyles. Such multi-level programs constitute macro-micro level and multi-component interventions designed to mobilize several resources in a concerted effort to reduce overweight and obesity, and thus reduce childhood risks for type 2 diabetes (Satcher and Higginbotham 2008). Strategies for changing environments to promote healthy lifestyles include environmental interventions to facilitate physical activity for diabetes prevention, creating a community consciousness regarding the effects of the built environment on physical health, and creating partnerships between various stakeholders including policymakers, community residents and health specialists (Srinivasan et al. 2003). Multi-faceted social policy recommendations to reduce obesity and physical inactivity now include: (a) establishing national dietary and physical activity guidelines, (b) improving the availability of healthy foods, (c) promoting physical activity, (d) changing unhealthy marketing practices, (e) public awareness campaigns, and (f) accurate nutritional labeling (Collagiuri et al. 2006).

Multi-level and developmental interactive effects affecting diabetes

High prevalence rates of type 2 diabetes have also been associated with acculturative changes although the relationship is complex and may exhibit more than one developmental or cultural pathway, that is, this process may differ for various Latino subgroups. For example, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis examined the prevalence of type 2 diabetes as associated with levels of acculturation among 708 Mexican-origin Latinos, 547 non-Mexican origin Latinos, and 737 Chinese immigrants and non-immigrants (Kandula et al. 2008). Level of acculturation was measured by an index defined by: nativity, years living in the US, and language spoken in the home. In within-group analyses and after adjustment for confounders, for each of three groups, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was significantly associated with acculturation in the non-Mexican Latinos, but not in the Mexican-origin Latinos nor in the Chinese. Among these Latino groups, this interaction effect (moderation by type of ethnic origin) suggested differential acculturation effects according to national heritage, thus implicating divergent acculturative mechanisms as influences on the risks for type 2 diabetes. This analysis involving “more homogeneous” sub-groups suggests differing developmental, dietary, physical activity, and other mechanisms that influence diabetes risks, implicating varied prevention intervention needs among various ethnic subgroups (Kandula et al. 2008).

As examined in other studies, both individual level and community-level factors can interact to influence physical activity. For example, among Latino women from a mid-Western community, Wilbur and colleagues observed that younger age, having an exercise partner, self-efficacy in doing exercise, exposure to others who exercise, living in a neighborhood having light traffic, and church attendance were factors from differing ecodevelopmental levels that were associated with a greater likelihood of engaging in physical activity (Wilbur et al. 2003). Similarly, in a study of eight perceived barriers to physical activity that was conducted in Brazil, Reichart et al. (2007) found a dose-response relationship in which an increasing number of perceived barriers was associated with greater physical inactivity. Among these perceived barriers were: a lack of time, a dislike of exercise, feeling too tired, a lack of money and a lack of exercise companions (Reichart et al. 2007). A combination of social stressors that are unique to certain minority groups, may also add to these barriers, stressors that can include racial discrimination, poverty, and immigration stressors.

Implications of the ecodevelopmental model for the design of scientifically based and culturally sensitive interventions

Challenges in intervention development and implementation

A major public health challenge in addressing existing health disparities among racial/ethnic minority populations involves the design of scientifically based prevention interventions (Flay et al. 2005) that are also culturally sensitive (Kumpfer et al. 2002) for promoting healthy behavior change within various special populations. The expanded ecodevelopmental models presented here offers frameworks for understanding the contexts that influence the onset of chronic degenerative diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, and that disproportionately affect ethnic minority populations. These models may aid in “mapping out” the various multi-level influences that contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes. In the next sections, we offer several ways in which these models can be applied to the design of effective culturally tailored prevention interventions.

Population segmentation and ethnic-subgroup analyses

Race/ethnicity often serves as a broad factor that can be useful for conceptualizing and planning prevention intervention programs. However, given the significant within-group heterogeneity that exists within each racial-ethnic group, it is useful to conduct population segmentation by indicators such as level of acculturation, a facet that can be regarded as being “nested” within the variable of ethnicity. Doing so can improve the analysis of sub-group effects to guide sub-group-specific health program planning. Population segmentation is a marketing research approach which until recently has lacked implementation within scientific research studies.

Specifically, epidemiological data has highlighted the presence of health disparities in association with broad racial/ethnic categories, although such analyses inadvertently gloss over this extensive within-group variability, i.e., “ethnic gloss” (Trimble 1995), thus obfuscating important differences among distinct segments within any racial/ethnic population. The health needs of such stratified or segmented subgroups can thus be considered in the design and implementation of more specifically tailored and ideally more effective and culturally sensitive prevention interventions. To improve program design, especially when developing more focused “Selective” prevention interventions (Kellum and Langevin 2003), population segmentation can be used to identify these more homogeneous sub-groups within a larger racial/ethnic population, as these may also differ in their risks of type 2 diabetes and in their intervention-related needs.

As one example, segmentation by three levels of acculturation (low acculturated, bilingual/bicultural, and high acculturated) can serve as a moderator approach for defining ordinal-level sub-population segments that exist within a Latino population (Castro et al. 2008). Similarly, a two-factor schema for population segmentation has been proposed that examines: (a) levels of education (lower and higher), as cross-tabulated with (b) levels of acculturation (Balcazar et al. 1995). More recent approaches to the identification of cohesive within-population segments have utilized cluster analysis (Ling et al. 2007), and also latent class analysis (Lubke and Muthen 2005). The use of these statistical methods might identify subgroups of Latinos that present greater resistance to behavior change relative to other groups. For example, lower-socioeconomic status, low-acculturated middle-aged Latinas, have distinctly different dietary and physical activity needs, motivations, and preparedness for diabetes prevention (King et al. 2000), as compared with middle-socioeconomic status, bicultural, middle-aged Latinas. In general, population segmentation avoids a “one-size-fits-all,” approach based on ethnicity. Health promotion and diabetes prevention interventions can thus be designed to address the needs of such specific segments within a racial/ethnic population.

Model expansion with cultural variables

Culturally relevant research and interventions that build on motivational determinants of healthy behavior change can benefit from expanding conventional scientific models, (e.g., the Health Belief Model), to include specific cultural variables that may influence certain health outcomes (Castro and Hernández-Alarcón 2002; Liburd et al. 2005). Certain cultural variables may operate as barriers or as facilitators in the reduction of diabetes risks. Consequently, behavior change strategies may need to be modified depending on a cultural group’s or a family’s traditional cultural values. Among Latino women, “marianismo” refers to a traditional female gender role identity that is characterized by devout and often submissive behaviors and dedicated caring for her husband, children and household (Gil and Vazquez 1996). Such devotion also involves considerable self-sacrifice and a certain image regarding the conduct that is considered appropriate for a married woman, i.e., a “señora.” A woman high in “marianismo” may perceive an identity or role incongruity regarding certain self-images and perceptions, e.g., that it is “not ladylike” or “not motherly,” for a middle-aged or elder “señora” to wear tennis shoes and exercise clothes, and to participate in aerobic exercise activities.

Along these lines, the ecodevelopmental models can provide guidance for recognizing strategies to improve support or to negotiate barriers in developing supportive networks for various Latinas. For example, given the central role of the family (la familia) within Latino and other ethnic minority cultures, the curriculum for a culturally responsive health promotion program as developed for Latinos(as) should consider abiding family influences, such as family obligations, conflicts, and disrupted family function (Farver et al. 2002; Prado et al. 2007), as contextual influences that can affect dietary and exercise behaviors. For these traditional Latinas, the use of community lay health workers (Promotoras) as trusted health advisors has been a useful approach for health promotion outreach, information dissemination, and the provision of social support particularly among rural populations (Reinschmidt et al. 2006; Rhodes et al. 2007). Other sources of support including support for these traditional Latinas from spouse, companionship, and child care (Thorton et al. 2006), can facilitate their participation in physical activity and in following a healthy diet.

Community participatory approaches

Collaborative and participatory approaches for diabetes prevention can provide racial/ethnic minority populations with culturally sensitive interventions that promote their involvement (Minkleret al. 2003). A major challenge to health promotion among minority community residents is that they are not a “captive audience,” that is easily accessed. Thus, this challenge involves successfully eliciting, initiating and maintaining their active participation in a program for diabetes prevention (Daviset al. 1998; Minkler et al. 2003).

This collaborative approach must ground the diabetes prevention program in the needs of identified sub-groups (Huff and Kline 1999). Using the ecodevelopmental model as a framework to conceptualize these varying needs as stratified by age group (childhood, adolescence, adulthood, old age) and other social and cultural factors (see Fig. 2), multi-level interventions can thus be designed to coordinate health interventions at two or more levels: organic, individual, familial, community, and sociocultural. Diabetes prevention to address energy imbalances also requires an understanding of a particular ethnic subgroup’s knowledge of diabetes, beliefs, customs and traditions regarding dietary and exercise behaviors, in other words, a “deep structure” understanding (Resnikow et al. 2000) of that group’s cultural and lifestyle behaviors as related to diabetes risks. Accordingly, this approach can address several aims that include: (a) providing program activities in a language and level of comprehension understandable to the consumer group (Tanjasiri et al. 2007); (b) employing culturally competent staff who can address issues of diet, exercise, and diabetes risks in a manner that is interesting and meaningful to consumers; and (c) integrating age and culturally relevant values and norms into core program components. These values include: family oriented values such as familism (strong family bonding and involvement in family activities), “confianza” (the importance of trust in a relationship), “personalismo” (the importance of treating a person with courtesy and proper attention), “respeto” (the value of trust and of being treated with respect), and “simpatia” (deference in interpersonal relationships used to maintain harmonious interpersonal relationships) (Castro and Hernández-Alarcón 2002; Marin and Marin 1991). Furthermore, other aims include: (d) tailoring or adapting intervention activities (Castro et al. 2004) in accord with the consumer group’s levels of acculturation, level of education or literacy, developmental age group; and (e) developing sensitivity to local community traditions and norms.

Conceptualizing cultural effects

In summary, integrating cultural factors into prevention interventions involves a proactive analysis of the needs of a specific cultural sub-group, and of how specific cultural factors (perceptions, attitudes, skills in self-regulation, family obligations, low social supports for a healthy lifestyle, etc.) may operate as personal or cultural barriers (or as facilitators) of sustained behavior change that can reduce the risks of type 2 diabetes. In the design of culturally sensitive prevention interventions, culturally relevant cognitive or relational factors can be explored as potential facilitators or detractors of healthy behavior change. These include: ethnic pride, familism, machismo, marianismo, personalismo, respeto, simpatia, and spirituality (Castro and Hernández-Alarcón 2002). Cultural factors that may operate as moderators of healthy behavior change may include: levels of acculturation, traditional values, as well as the traditional gender roles of machismo and marianismo. Broader contextual factors include aspects of the built environment, as well as local norms and national policies that influence lifestyle choices. Consideration of these factors may augment cultural sensitivity, ideally facilitating program participation and thus enhancing the efficacy of interventions designed to change dietary and exercise behaviors consistent with diabetes prevention.

A final comment

We have summarized several key approaches for overcoming challenges to diabetes prevention in Latino and other racial/ethnic populations, with the aim of informing the design of more effective diabetes prevention interventions. The diversity that exists within each ethnic group must thus be recognized and addressed by the use of population segmentation that identifies ethnic-cultural subgroups (strata) that can be defined by socioeconomic status, level of education or literacy, age group, and perhaps by gender, as this segmentation aids in focusing the content of the prevention intervention curriculum. Subsequently, various findings from empirical studies can be considered as the basis for prevention intervention planning and design. This greater focus on defining features of racial/ethnic minority sub-groups can be guided by the expanded ecodevelopmental models and via the conduct of research on the hypotheses suggested by such model analyses. This approach may further enrich our understanding of ways to facilitate the prevention and control of type 2 diabetes in Latino and other racial/ethnic minority populations.

References

Albu, J. B., Kovera, A. J., Allen, L., Wainwright, M., Berk, E., Raja-Khan, N., et al. (2005). Independent association of insulin resistance with larger amounts of intermuscular adipose tissue and a greater acute insulin response to glucose in African American than in white nondiabetic women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 82, 1210–1217.

American Diabetes Association (2008). All about diabetes. http://www.diabetes.org/about-diabetes.jsp. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

Arcury, T. A., Skelly, A. H., Gesler, W. M., & Dougherty, M. C. (2004). Diabetes meanings among those without diabetes: Explanatory models of immigrant Latinos in rural North Carolina. Social Science & Medicine, 59(11), 2183–2193. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.024.

Balcazar, H., Castro, F. G., & Krull, J. L. (1995). Cancer risk reduction in Mexican American women: The role of acculturation, education, and health risk factors. Health Education Quarterly, 22, 61–84.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Baptiste-Roberts, K., Gary, T. L., Beckles, G. L. A., Gregg, E. W., Owens, M., Porterfield, D., et al. (2007). Family history of diabetes, awareness of risk factors, and health behaviors among African Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 907–912. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.077032.

Barnes, P. M., Adams, P. F., & Powell-Griner, E. (2008). Health characteristics of the Asian adult population: United States, 2004–2006. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, 394, 1–24.

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 697–712.

Bollen, K. A., & Curran, P. J. (2006). Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Bonham, V. L. (2005). Race and ethnicity in the genome era: The complexity of the constructs. The American Psychologist, 60, 9–15. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.9.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723–724. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723.

Brownson, R. C., Baker, E. A., Housemann, R. A., Brennan, L. K., & Bacak, S. J. (2001). Environmental policy and determinants of physical activity in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1995–2003. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1995.

Byrne, B. M. (2006). Structural equation modeling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications and programming (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Castro, F. G. (2007). Is acculturation really detrimental to health? American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1162. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.116145.

Castro, F. G., Balcazar, & Cota, M. (2008). Health promotion in Latino populations: program planning, development, implementation and evaluation. In M. V. Kline & R. M. Huff (Eds.), Promoting health in multicultural populations: A handbook for practitioners (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Castro, F. G., Barrera, M., & Martinez, C. R. (2004). The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science, 5, 41–45. doi:10.1023/B:PREV.0000013980.12412.cd.

Castro, F. G., & Coe, K. (2007). Traditions and alcohol use: A mixed-methods analysis. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 269–284. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.269.

Castro, F. G., & Hernández-Alarcón, E. (2002). Integrating cultural factors into drug abuse prevention and treatment with racial/ethnic minorities. Journal of Drug Issues, 32, 783–810.

Census, US (2008a). Racial and ethnic classification used census 2000 and beyond. http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/race/racefactscb.html. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

Census, US (2008b). Minority links. http://www.census.gov/pubinfo/www/hotlinks.html. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

Chesla, C. A., Fisher, L., Skaff, M. M., Millan, J. T., Gilliss, C. L., & Kanter, R. (2003). Family predictors of disease management over one year in Latino and European American patients with type 2 diabetes. Family Process, 42, 375–390. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00375.x.

Clark, R., Anderson, N. B., Clark, V. R., & Williams, D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans. The American Psychologist, 54, 805–816. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805.

Collagiuri, R., Collagiuri, S., Yach, D., & Pramming, S. (2006). The answer to diabetes prevention: Science, surgery, service delivery or policy? American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1562–1569. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.067587.

Coronado, G. D., Thompson, B., Tejeda, S., Bodina, R., & Chen, L. (2007). Sociodemographic factors and self-management practices related to type 2 diabetes among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites in a rural setting. The Journal of Rural Health, 23, 49–54. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00067.x.

Crespo, C. J., Smit, E., Anderson, R. E., Carter-Pokras, O., & Ainsworth, B. E. (2000). Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Study 1988–1994. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 18, 46–53. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00105-1.

Dagogo-Jack, S. (2003). Ethnic disparities in type 2 diabetes: Pathophysiology and implications for prevention and management. Journal of the American Medical Association, 95, 774–789.

Davis, J. R., Schwartz, R., Wheeler, F., & Lancaster, R. B. (1998). Intervention methods for chronic disease control. In R. C. Brownson, P. L. Remington, & J. R. Davis (Eds.), Chronic disease epidemiology and control (pp. 77–116). Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

De Filippis, E., Alvarez, G., Berria, R., Cusi, K., Everman, S., Meyer, C., et al. (2008). Insulin-resistant muscle is exercise resistant: Evidence for reduced response of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes to exercise. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 294, E607–E614. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00729.2007.

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. (2002). Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. The New England Journal of Medicine, 346, 393–403. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa012512.

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge to biomedicine. Science, 196, 129–136. doi:10.1126/science.847460.

Farver, J. M., Narang, S. K., & Bhadha, B. R. (2002). East meets west: Ethnic identity, acculturation, and conflict in Asian Indian families. Journal of Family Psychology, 16, 338–350. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.16.3.338.

Ferrannini, E., Gastaldelli, A., Miyazaki, Y., Matsuda, M., Mari, A., & DeFronzo, R. A. (2005). Beta-cell function in subjects spanning the range from normal glucose tolerance to overt diabetes: A new analysis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 90, 493–500. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1133.

Flay, B., Biglan, A., Bourch, R. F., Castro, F. G., Gottfriedson, D., Kellem, E. K., et al. (2005). Standards of evidence: Criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prevention Science, 6, 151–175. doi:10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y.

Frone, M. R. (2008). Are work stressors related to employee substance use? The importance of temporal context in assessments of alcohol and illicit drug use. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 199–206. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.199.

Gardner, L. I., Stern, M. P., Haffner, S. M., Gaskill, S. P., Hazuda, H. P., Relethford, J. H., et al. (1984). Prevalence of diabetes in Mexican Americans: Relationship of percent gene pool derived from native American sources. Diabetes, 33, 86–92. doi:10.2337/diabetes.33.1.86.

Gil, R. M., & Vazquez, C. J. (1996). The Maria paradox: How Latinas can merge old world traditions with new world self-esteem. New York: Berkeley Publishing.

Goran, M. I., Bergman, R. N., Cruz, M. L., & Watanabe, R. (2002). Insulin resistance and associated compensatory responses in African-American and Hispanic children. Diabetes Care, 25, 2184–2190. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.12.2184.

Guyton, A. C. (1981). Textbook of medical physiology (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders.

Haffner, S. M., Stern, M. P., Hazuda, H. P., Pugh, J. A., & Patterson, J. K. (1986). Hyperinsulinemia in a population at high risk for non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The New England Journal of Medicine, 315, 220–224.

Harwood, A. (1981). Ethnicity and medical care. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Heo, M., Faith, M. S., Mott, J. W., Gorman, B. S., Redden, D. T., & Allison, D. B. (2004). Hierarchical linear models for the development of growth curves: An example with body mass index in overweight/obese adults. In R. B. D’Agostino (Ed.), Tutorials in biostatistics: Statistical modeling of complex medical data (Vol. 2). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Herbert, H. B., Snider, J., & Winkleby, M. A. (2005). Health status, health behaviors, and acculturation factors associated with overweight and obesity in Latinos from a community and agricultural labor camp survey. Preventive Medicine, 40, 642–651. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.001.

Horowitz, C. R., Colson, K. A., Hebert, P. L., & Lancaster, K. (2004). Barriers to buying healthy foods for people with diabetes: Evidence of environmental disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 1549–1554.

Horsley, K., & Ciske, S. J. (2005). From neurons to King County neighborhoods: Partnering to promote policies based on the science of early childhood development. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 562–567. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.048207.

Hovell, M. F., Mulvihill, M. M., Buono, M. J., Liles, S., Schade, D. H., Washington, T. A., et al. (2008). Culturally tailored aerobic exercise intervention for low-income Latinas. American Journal of Health Promotion, 22(3), 155–163.

Huff, R. M., & Kline, M. V. (1999). Promoting health in multicultural populations: A handbook for practitioners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Institute of Medicine. (2003). The future of the public’s health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ivy, J. L. (1997). Role of exercise training in the prevention and treatment of insulin resistance and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 24, 321–336.

Jensen, C. C., Cnop, M., Hull, R. L., & Fujimoto, W. Y. (2005). Contributor to oral glucose tolerance in high-risk relatives of four ethnic groups in the US. Diabetes, 21, 2170–2178.

Joffee, M., & Mindell, J. (2006). Complex causal process diagrams for analyzing the health impacts of policy interventions. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 473–479. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.063693.

Jones, D. S. (2006). The persistence of American Indian health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 2122–2134. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.054262.

Kandula, N. R., Diez-Roux, A. V., Chan, C., Daviglus, M. L., Jackson, S. A., Ni, H., et al. (2008). Association of acculturation levels and prevalence of diabetes in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care, 31, 1621–1628. doi:10.2337/dc07-2182.

Kellum, S. G., & Langevin, D. J. (2003). A framework for understanding “evidence” in prevention research and programs. Prevention Science, 4, 137–153. doi:10.1023/A:1024693321963.

King, A. C., Castro, C., Wilcox, S., Eyler, A. A., Sallis, J. F., & Brownson, R. C. (2000). Personal and environmental factors associated with physical inactivity among different racial-ethnic groups of US middle-aged and older women. Health Psychology, 19, 354–364. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.19.4.354.

Kosti, R. I., Panagiotakos, D. B., Tountas, Y., Mihas, C. C., Alevizos, A., Mariolis, T., et al. (2008). Parental body mass index in association with the prevalence of overweight/obesity among adolescents in Greece; dietary and lifestyle habits in the context of the family environment: The Vyromas study. Appetite, 51, 218–222. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2008.02.001.

Kreft, I., & De Leeuw, J. (1998). Introducing multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kumpfer, K. L., Alvarado, R., Smith, P., & Bellamy, N. (2002). Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions. Prevention Science, 3, 241–246. doi:10.1023/A:1019902902119.

Liburd, L. C., Jack, L., Williams, S., & Tucker, P. (2005). Intervening on the social determinants of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 29, 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.013.

Lillioja, S., Mott, D. M., Howard, B. V., Bennett, P. H., Yki-Jarvinen, H., Freymond, D., et al. (1988). Impaired glucose tolerance as a disorder of insulin action: Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies in Pima Indians. The New England Journal of Medicine, 318, 1217–1225.

Ling, P. M., Neilands, T. B., Nguyen, T. T., & Kaplan, C. P. (2007). Psychographic segments based on attitudes about smoking and lifestyle among Vietnamese-American adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 51–60. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.004.

Locke, D. C. (1998). Increasing multicultural understanding: A comprehensive model (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lubke, G. H., & Muthen, B. (2005). Investigating population heterogeneity with factor mixture models. Psychological Methods, 10, 21–39. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.10.1.21.

Marin, G., & Marin, B. V. (1991). Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

McGoldrick, M., & Giodano, J. (1996). Overview: Ethnicity and family therapy. In M. McGoldrick, J. K. Pearce, & J. Giordano (Eds.), Ethnicity and family therapy (2nd ed., pp. 1–27). New York: Guilford.

Meyerowitz, B. E., Richardson, J., Hudson, S., & Leedham, B. (1998). Ethnicity and cancer outcomes: Behavioral and psychosocial considerations. Psychological Bulletin, 123, 47–70. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.123.1.47.

Minkler, M., Blackwell, A. G., Thompson, M., & Tamir, H. (2003). Community-based participatory research: Implications for public health funding. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1210–1213.

Moskowitz, J. T., Epel, E. S., & Acree, M. (2008). Positive affect uniquely predicts lower risk of mortality in people with diabetes. Health Psychology, 27(Suppl. 1), 73–82. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S73.

Pagoto, S. L., Kantor, L., Bodenlos, J. S., Gitkind, M., & Ma, Y. (2008). Translating the diabetes prevention program into a hospital-based weight loss program. Health Psychology, 27(Suppl.), S91–S98. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S91.

Pan, E., & Farrell, M. P. (2006). Ethnic differences in the effects of intergenerational relations on adolescent problem behavior in US single-mother families. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1137–1158. doi:10.1177/0192513X06288123.

Pantin, H., Schwartz, S. J., Sullivan, S., Prado, G., & Szapocznik, J. (2004). Ecodevelopmental HIV prevention program for Hispanic adolescents. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74, 545–588. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.545.

Plascia, M., Herrick, H., & Chavis, L. (2008). Improving health behaviors in an African American community: The Charlotte racial and ethnic approaches to community health project. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1678–1684. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.125062.