Abstract

There has been much debate about how to measure psychopathic traits in adolescence. One of the main issues is whether one should focus on callous-unemotional (CU) traits alone, or CU traits in combination with Grandiose-Manipulative (GM) and Daring-Impulsive (DI) traits. The current study first investigates the extent to which youth who are high on CU traits are also high on GM and DI traits. In addition, the study investigates if being high on both CU and GM, and high on both CU and DI, identify groups that are particularly characterized by past and future impairments. To investigate this, data from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (CSDD) was analyzed. The CSDD is a prospective longitudinal study of 411 English boys spanning over 50 years. The information available at age 12–14 was coded on the Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD). Childhood risk factors were measured at age 8–10 and later life outcomes were measured at age 32. The results indicate that being high on CU in combination with DI delineates a clinically interesting group who are characterized by high childhood risk and poorer adult life outcomes. The same applied to the high CU/high GM group, but to a lesser extent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“Teachers, scoutmasters, the school principal, etc., recognized that in some very important respects he differed from the ordinary bad or wayward youth” – Cleckley 1941/1988, p. 66

More than “Bad and Wayward”: Psychopathic Traits in Adolescence

Recently, Salekin (2017) conducted a review to clarify the understanding of the extension of psychopathic traits downward from adulthood to adolescence and childhood, and to establish some central tenets about the structure, development, and problematic outcomes of psychopathic traits based on studies published across a 27-year period. Salekin’s (2017) review was much needed in a field where the measurement of psychopathic traits in adolescence has been highly debated in the past 20–30 years (Farrington 2005; Salekin 2016a, 2016b; Salekin and Lynam 2010; Seagrave and Grisso 2002). This debate has been reinvigorated by the new callous unemotional (CU) (with limited prosocial emotion – LPE) specifier in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013) for the behaviorally based Conduct Disorder (CD) (Salekin 2017). The current study is an attempt to investigate some of the issues raised by Salekin (2017), specifically which childhood risk factors are associated with psychopathic traits, and the extent to which psychopathic traits in adolescence predict outcomes in adulthood. As such, the study has utility for clinical practice as well as for the overall understanding of psychopathy in adolescence.

Two main positions have been taken on how to best measure psychopathic traits in childhood and adolescence. On one hand, Frick and colleagues (e.g. Christian et al. 1997; Essau et al. 2006; Frick et al. 2014; Frick and White 2008; Kahn et al. 2012) and others (e.g. Barry et al. 2000; Scheepers et al. 2011) have argued that the best way to assess the most clinically impaired group is to assess CU traits (characterized by for example empathy deficiencies and low responsibility to others or guilt; American Psychiatric Association 2013; Colins and Vermeiren 2013; Frick and White 2008) in children and youth with CD. The reasoning behind the emphasis on CU traits is that, among children and youth who present problematic behavior and norm-breaking behavior, CU traits are likely to identify an especially problematic group who have an elevated risk of future problems and poor life outcomes (Frogner et al. 2018), including adult psychopathy (Hawes et al. 2016). The focus on CU traits would also make the identification of potential psychopathic traits easier by disregarding problematic behavior that over time could turn out to be fairly normative adolescent behavior (Frick 2016; Frick et al. 2014; Moffitt 1993; Seagrave and Grisso 2002), and by also reducing concerns about the heterogeneity of the psychopathy construct in childhood and adolescence (Salekin 2017).

On the other hand, Salekin (2016a, b) argues that the inclusion of only a CU specifier is too reductionist, and that researchers should focus on a more multidimensional psychopathic personality (CU plus Grandiose-Manipulative and Daring-Impulsive) (Salekin 2017). To increase clarity about the psychopathy construct in childhood, CU should be considered as a component of an overarching construct alongside other relevant dimensions (i.e. grandiose traits/narcissism, manipulativeness, impulsivity). Salekin (2016a) also argues that the DSM CD diagnosis is too far removed from the concept of psychopathic traits without the inclusion of grandiose-manipulative traits and impulsive behavior. There are also concerns that research on youths and children who are both high on CU and CD does not take account of other psychopathic traits that might influence the potential relationships between CU and problematic behavior (Frogner et al. 2018). Without more emphasis on these other traits in addition to CU traits, the confusion around CD and psychopathy will continue to create problems for the understanding of psychopathic traits in adolescence.

Clinically Impaired Group (-s)?

Recent findings indicate that there are different physiological correlates of the clusters of traits that make up the total psychopathy construct in young people (Fanti et al. 2017). If an evidence-based decision is to be made about whether to focus only on CU traits or on the whole psychopathy construct including traits related to grandiose-manipulative (GM) and daring-impulsive (DI) traits, the clinical impairments associated with the traits, singly and in combination, must be investigated (Salekin 2016b, 2017; Waller et al. 2015). Salekin (2016a, b, 2017) criticizes the assumption that CU traits are the most central part of adolescent psychopathy, in the absence of further research on the phenotypes and nomological networks of all the potentially relevant traits.

Recent reviews have established the utility of environmental (e.g. parental and peer) factors in predicting CU traits, as well as the other dimensions or trait-clusters included in the psychopathy construct (e.g. Waller et al. 2013). Harsh parental discipline (including child abuse) contributes to the development of CU traits. These findings were consistent across childhood and adolescence, and have been later confirmed in other studies (Waller et al. 2016), and in studies on interpersonal callousness (IC traits) (Byrd et al. 2016). Salekin (2017) reviewed the available literature on parenting practices and the development of psychopathic traits. While he criticized the available literature for flawed methodology, the research indicated that undesirable parenting practices (e.g. harsh, physical, emotional) were predictive of psychopathic traits, but also surprisingly that the positive end of these risk factors (commonly viewed as protective factors) can contribute to the development of psychopathic traits in children.

IQ also shows interesting relationships with the different dimensions of psychopathy. Salekin (2017) concluded that IQ is strongly related to GM and CU, but in opposite directions. Little research has investigated whether the same applies to socioenvironmental factors. These studies, albeit few and far between, are beneficial as they provide a better understanding of predictors of the full psychopathic personality in adolescence, as opposed to just one of its facets such as CU traits.

Long-Term Impairments

It is well known that psychopathic traits are associated with a wide array of antisocial outcomes and impairments. The co-occurrence of psychopathy (total and facets) and offending is well-established, as well as the fact that adolescent and adult psychopathic traits predict recidivism and violent behavior (Blais et al. 2014; Edens et al. 2007; Gretton et al. 2004; Hare 1993; Salekin 2008). CU traits have been shown to predict antisocial outcomes among high risk youths (Dadds et al. 2005; Fontaine et al. 2011; McMahon et al. 2010). However, in a comprehensive review, Frick and White (2008) conclude that it is difficult to determine which, if any, of the clusters of adolescent psychopathic traits are most predictive of later antisocial outcomes. Research indicates that the multidimensional psychopathic personality predicts a wide range of undesirable outcomes, such as aggression (Andershed et al. 2018), bullying (Van Geel et al. 2016), serious and stable antisocial behavior (Salihovic and Stattin 2016), stable conduct disorder (Frogner et al. 2016), and ADHD (Frogner et al. 2018). It must however be noted that some research suggests that psychopathic traits in adolescence are not related to criminality (Colins et al. 2017).

Less research attention has been paid to other, non-violent, life outcomes. What we do know, however, is that psychopathic traits are negatively related to life success in the areas of status, wealth, and intimate relationships (Ullrich et al. 2008). Other research also indicates that being high on CU traits and/or the full multidimensional psychopathic personality is associated with employment problems (Spurk et al. 2015), substance abuse (alcohol and drugs) (Andershed et al. 2018; Gillen et al. 2016; Hemphill et al. 1994; Mailloux et al. 1997; Smith and Newman 1990), rule-breaking (Colins et al. 2016a), mood disorders (Colins et al. 2016a, b), and fearlessness (Frogner et al. 2018). Difficulties in life functioning are perhaps not surprising in light of the definition of a personality disorder, which includes a pattern of personality and behavior that has interfered with everyday functioning (Section II, American Psychiatric Association 2013).

The Current Study: Research Questions

The current study aims to address some of the most central research questions identified by Salekin (2017), by investigating to what extent CU traits identify a clinically impaired and high risk group of youths, and to what extent the combination of CU traits with GM or DI identify a clinically more meaningful group. First, the study will investigate to what extent high CU scorers are also high on GM and DI in adolescence. Based on both Frick and colleagues (e.g. Essau et al. 2006; Fink et al. 2012; Frick et al. 2014; Frick 2016) and Salekin’s (2016a, b) research and arguments, it is hypothesized that high CU scorers will be similarly high on GM and DI. If these factors are indeed related to each other, this would mean that Salekin’s (2016a, 2016b) request for further inclusion of specifiers in the CD diagnosis is supported. Second, the present study will explore the nomological network by investigating how childhood risk factors at age 8–10 are related to psychopathic traits at age 12–14, and to what extent the risk factors and psychopathic traits are predictive of later life outcomes at age 32. This way it will be possible to identify high risk groups that are characterized by long-term life impairments.

Since there might be some divergence in the nomological networks of the personality oriented traits versus those that are more behaviorally based (Salihovic and Stattin 2016), this study will follow the recommendations of Salihovic and Stattin (2016) by creating dichotomized groups (e.g. those who are high on both CU traits and DI). Salihovic and Stattin (2016) outlined concerns about measurement overlap between personality and behavioral traits, and argued that part of the predictive utility of CU traits is attributable to this overlap. In support of this, Ansel et al. (2015) argued that CU traits should not be treated as a unidimensional construct. Salekin (2017) argued that the next step for researchers is to investigate interactions between the psychopathy dimensions and how they relate to outcomes of interest. The literature on such interactions is still somewhat scarce, and the results are mixed. Some authors have found that it is the combination, or interaction, between the CU, GM, and behaviorally oriented factors (i.e. DI) that best predict violent and self-directed violent outcomes (Lee-Rowland et al. 2017; Verona et al. 2012; Walsh and Kosson 2008), while others have not found this association (Kennealy et al. 2010).

Another issue is the lack of studies on adult and middle-age outcomes. While efforts have been made in this article to identify studies with long follow-ups, there are very few of these. The most likely reason for this is the lack of prospective longitudinal studies within psychopathy research as a whole (Farrington and Bergstrøm in press). Because of the lack of a broader criminological risk factor perspective on predictors of psychopathic traits, the current study is exploratory in nature and includes childhood risk factors that have been found to predict psychopathic traits in adulthood (for a thorough overview, see Farrington and Bergstrøm in press).

Methodology

Sample and Design

The current study analyzes data from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (CSDD), a prospective longitudinal study that has followed 411 boys from a lower class London community for half a century (see Farrington 1995, 2003; Farrington et al. 2009, 2013). The first data collection took place when the boys were age 8 (in 1961–1962), and they were assessed on a regular basis until the age of 18. The collected data was comprehensive, including official criminal records, self-reports and interviews with the boys, interviews with parents and teachers, as well as peer ratings. After the age of 15, the data consisted only of official records, self-reports and interviews with the boys. Attrition across time was very low. At age 32, 94% of the males who were still alive were interviewed. At age 48, 93% of the males who were still alive were interviewed. The present article focuses on outcomes at age 32.

Measures

Psychopathic Traits in Adolescence: Adolescent Process Screening Device (APSD; Frick and Hare 2001)

As previously highlighted in Bergstrøm et al. (2016), measures of psychopathic traits were not included in the original CSDD data collection in the 1960s. However, using the comprehensive data available across childhood and adolescence, it was possible to code the boys retrospectively (but based on prospectively collected information) using the Adolescent Process Screening Device (APSD; Frick and Hare 2001). This is a reanalysis strategy that has previously been endorsed by Salekin and Lynam (2010) given the uniqueness of the sample, and while it arguably could reduce the reliability of the final results, the scoring was considered sound (see Bergstrøm et al. 2016). The APSD (Frick and Hare 2001) measures psychopathic traits in children as young as 6 years of age. For the current study, the information was coded at age 12–14, in order to ensure a wealth of data as the foundation for the coding (Bergstrøm et al. 2016).

The APSD (Frick and Hare 2001) consists of 20 items (measured on the traditional 3 point ordinal scale of 0, 1, and 2 common to the PCL tradition) that load onto three underlying subscales: Callous-Unemotional (CU), Narcissism (NAR), and Impulsivity (IMP). For conceptual clearness, we will here refer to these as GM (NAR), CU (CU), and DI (IMP) in accordance with Salekin (2017). Two items did not load on to any of the factors, but were included in the total score (Frick and Hare 2001). Nineteen out of the total 20 items could be coded in the present research, and the item that could not be coded loaded onto the GM factor. The total scale and GM subscale in question were prorated to reflect 20 and 7 items respectively, which is in accordance with the PCL tradition (Hare and Neumann 2005).

At age 12–14, Cronbach’s alpha for the total APSD (APSD TOT) score was .62, while the subscales had the following alphas: .29 (GM), .17 (CU), and .43 (DI). The low Cronbach’s alphas may be considered problematic, but the use of Cronbach’s alpha has been criticized as a measure of reliability (Sijtsma 2009). It is greatly affected by issues such as missing data and data imputation (Van Ginkel et al. 2007), a small number of items in a scale (Bland and Altman 1997) and the range of response alternatives on the items (Farrington et al. 2006; Gadermann et al. 2012). Waller et al. (2013), also highlighted the poor internal validity of the CU measures utilized. It must also be noted that 23% (7/30) of the reviewed studies did not provide Cronbach’s alpha. The poor internal consistency (lowest reported: .40) in Waller et al. (2013) is however not that surprising since it is typically easier to assess behavior reliably compared to more latent expressions of personality (Kiehl and Hoffman 2011). The APSD is based on the PCL-R (Frick and Hare 2001), and it has been widely used in the child and adolescent psychopathy literature, despite its generally low alpha values (Falkenbach et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2003; Munoz and Frick 2007; Vitacco et al. 2003).

The total score and GM, CU, and DI scores were dichotomized into high/low. The high scoring groups were identified as the approximately highest 30% of the sample (although this did depend somewhat on the distribution of the scale in question). The reason for the choice of 30% was to be able to create groups (e.g. high CU/high GM) of meaningful size. Previous research also indicates that the percentile used for dichotomization does not influence the results significantly (Farrington and Loeber 2000; Frogner et al. 2018). A score of 1 indicates a low score, while 2 indicates a high score. Based on this dichotomization, and bearing in mind our main interest in investigating whether the combination of CU traits and other psychopathic traits identified a clinically meaning category, the following groups were created: High CU/High GM and High CU/High DI.

Risk Factors at Age 8–10

Ten risk factors measured at age 8–10 were included in the current study. These measured parenting practices (harsh-erratic discipline, poor child-rearing, and poor supervision), characteristics of parents (young mother, convicted parent, parental disharmony), and socioeconomic (large family size, poor housing, low income, low SES). These were selected on the basis of previous literature on which childhood factors predicted adult psychopathic behavior (e.g. Farrington and Bergstrøm 2018). All of these variables were dichotomized (1 and 2), where 2 indicates the more negative outcome (e.g. “has experienced poor parental supervision”).

Offending Outcome Variables at Age 32

Two types of offending outcomes at age 32 were measured; self-reported offenses and whether or not the males had been convicted in the past 5 years (also see Farrington et al. 2006). As with the risk factors, these outcome variables were dichotomized (1 and 2), where the latter indicates an offender.

Life Outcomes at Age 32

A total of nine comparable criteria were derived based on the interviews at age 32 (see Farrington et al. 2006). For the current study, five of these were used (seven in total when including the offending outcomes): problems with accommodation, cohabitation, and employment, as well as alcohol problems and drug abuse (in the past 5 years). As with the offending outcomes, they were dichotomized (1 and 2; 2 being the more negative outcome).

Analysis Plan

To assess whether those who are high on CU traits are also high on GM, and DI, cross tabulations were conducted with calculated odds-ratios. To investigate the relationship between risk factors and psychopathic traits and life outcomes, odds ratios were calculated. The odds-ratios permit the identification of the characteristics and outcomes of the top scorers on the different psychopathic traits. For more on the benefits of dichotomization, see Farrington and Loeber (2000). Dichotomized groups were also created (e.g. High on CU/high on GM, high on CU/high on DI) and odds ratios were calculated to investigate the relationships between these groups and risk factors and offending and other life outcomes.

Results

Consistency Across Factors and Total Score

Table 1 presents those who are high and low on CU traits and their relationship with GM and DI at age 12–14. As can be seen from the table, 35.2% (n = 32) of the high CU scorers were high on both CU traits and GM, while 49.5% (n = 45) were high on both CU traits and DI. Interestingly, high CU scores were not significantly related to high GM scores, but high CU scores were significantly related to high DI scores.

Risk and Impairment

Childhood risk factors were investigated in relation to the groups identified in Table 1. Table 2 divides the high CU scorers according to whether they were also high on GM and DI. The percentages with each factor are shown; for example, 46.7% of those who were high on both CU and GM had experienced harsh-erratic discipline, compared with 22.4% of those who were high on CU but not on GM. As can be seen from these columns, harsh-erratic discipline increased the risk of being high on both GM as well as CU, and so did having a convicted parent. Turning to later life outcomes, being high on GM as well as CU increased the risk of being convicted in adulthood and of engaging in fighting and problematic drinking behavior. There are not many significant results because of the small numbers being compared.

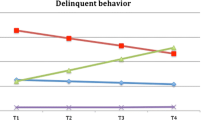

Interestingly, harsh-erratic discipline and having a convicted parent increased the risk of being high on DI as well as CU. Poor child-rearing, poor supervision, and parental disharmony were additional significant risk factors. While the ORs for self-reported offending and convictions were high (OR = 3.56 and OR = 3.28), these were not significant on a two-tailed test. They were, however, significant on a one-tailed test. One-tailed tests are justifiable here because of directional predictions. Being high on DI as well as CU was also significantly associated with later fighting, drug abuse, and drinking problems.

High CU: Risk Factors and Life Outcomes

The high CU/high GM and high CU/high DI groups are clearly different from the high CU/low GM and high CU/high DI groups on childhood risk factors and later life outcomes. However, are they qualitatively different, or are they merely quantitatively different, becaucse the high/high groups have higher CU than the high/low groups? In order to investigate this question, we studied the highest CU groups that were of some size as the high/high groups. Table 3 shows the relationships between the risk factors and outcomes and these groups (i.e. top 91 on CU versus the rest of the sample, top 32 versus the next 59 on CU traits, and top 45 versus the next 46 on CU traits). As can be seen from Table 3, the size of the top CU group does appear to have an effect on risk. The top 32 can be compared the the 32 high on both CU and GM, while the top 45 on CU can be compared the 45 high on both CU and DI. The top 32 and 45 boys on CU were associated with low non-verbal IQ, poor child-rearing (only top 32), fighting, and drinking problems (only top 45). However, it was clear that the high CU/high GM and high CU/high DI groups were significantly associated with more childhood risk factors and more adverse adult outcomes. Threfore, the greater impairment of these groups was not solely created by identifying high CU scorers; the particular combinations of psychopathic traits identified particularly impaired groups.

Discussion

Adolescent Psychopathic Traits: Just “Wayward” Youths?

The aim of the current study was to address some of the main issues raised by Salekin (2017) by investigating whether CU traits alone delineate a clinically meaningful group with elevated risk factors and adult, or whether CU traits in combination with high GM and DI are more clinically meaningful. The results indicate that those who were high on CU also tended to be high on DI, but not on GM. On one hand, this does indicate that CU traits are associated with behaviorally oriented and impulsive traits. The co-occurrence of CU traits and impulsive behavior is well established in the literature (e.g. Frick et al. 2014; Frick and White 2008). However, the lack of a relationship between high CU and high GM is surprising, since GM and CU have some conceptually similar items (Frick and Hare 2001).

There are several potential reasons for this lack of a relationship. For example, there have been mixed findings on the factor structure of the APSD, and that might in turn have affected the relationship in the current study (Falkenbach et al. 2003; Vitacco et al. 2003). Another potential reason is the particular cut-offs used. Because of the distribution of the data, it was difficult to create equal groups on all the dimensions, although this is unlikely to have influenced the results much (Farrington and Loeber 2000; Frogner et al. 2018). The results do however highlight the argument by Salekin (2017) that CU scales need to be better defined, and that there must be conceptually clearer divides between CU and other psychopathy traits or dimensions. In terms of the LPE specifier in the CD DSM-5 diagnosis, Salekin (2017) recommends against using the traditional CU psychopathy scales and suggests creating a specific CU measure that is less likely to overlap with other dimensions.

Are Combinations of Psychopathic Traits Clinically more Useful than High CU Alone?

Compared to high CU alone, it does appear that that the combinations of being high on CU and high on GM (high CU/high GM) and being high on CU and high on DI (high CU/high DI) are associated with a wider array of childhood risk factors. The high CU/high GM group were more likely to have experienced harsh-erratic discipline, and again this is in accordance with previous literature (Salekin 2017).This group (high CU/high GM) were also more likely to have had a convicted parent, which could reflect intergenerational transmission (e.g. Auty et al. 2015). The high CU/high GM group also had more antisocial outcomes at age 32 than CU without GM, including convictions, fighting, and drinking (drug abuse was close to significance, p = .051).

The high CU/high DI group appears to be the most impaired group with the most elevated risk. This group had experienced a greater range of risk factors, such as harsh-erratic discipline, poor child-rearing, poor supervision, convicted parents, and parental disharmony. The high CU/high DI group also showed long-term impairment through its prediction of self-reported offending, convictions, fighting, drug abuse, and drinking problems.

The results of the current study support earlier findings (Lee-Rowland et al. 2017; Salihovic and Stattin’s 2016; Verona et al. 2012; Walsh and Kosson 2008) that it is the combination of psychopathic traits that is the strongest predictor of antisocial and life outcomes, especially when it comes to offending, fighting, drug abuse, and drinking problems. The consistency with which psychopathic traits predict substance abuse lends support to previous research (Andershed et al. 2018; Gillen et al. 2016; Hemphill et al. 1994; Mailloux et al. 1997; Smith and Newman 1990), and shows the importance of continued research into psychopathy and substance use/abuse.

Implications

Adolescent psychopathic traits are clearly useful for predicting antisocial outcomes and offending in adulthood and middle age, and as a result could be a target for interventions (Forth et al. 2003). The aim of the current study was to address some of the areas in need of future research as outlined by Salekin (2017), and more specifically whether youth high on CU traits delineate a clinically impaired group compared to groups with several psychopathic traits. The new LPE specifier in the DSM-5 CD diagnosis very much relies on this notion of CU as core to the psychopathy construct (Salekin 2017), but Salekin (2016a, b, 2017) is concerned that the narrow focus on CU could halt progress in the field of child and youth psychopathy.

The results of the current study indicate that being very high on CU alone does not delineate a group of especially high-risk youth. That group is not particularly high on common risk factors, and it does not predict many antisocial outcomes, therefore questioning this approach to youth psychopathy. Since the results indicate that combinations of CU and GM and DI (separately) identify groups that are of elevated risk and show clinical utility in predicting antisocial outcomes, it would be better to follow Salekin’s (2016a, b) argument that the CD diagnosis could benefit from additional specifiers.

Strengths and Limitations

As is common with most studies, the current study has some limitations that should be discussed. The main limitation is that the assessment of adolescent psychopathic traits was conducted on archival data. It could be argued that interpersonal and affective traits might be difficult to assess validly without personal contact, but assessing psychopathic traits in older longitudinal studies in this manner has been recommended by Salekin and Lynam (2010). Another potential weakness is the use of the APSD (Frick and Hare 2001). Albeit widely used and validated (Frick et al. 2003; Douglas et al. 2008; Munoz and Frick 2007; Lee et al. 2003), its factor structure is contested (Falkenbach et al. 2003; Vitacco et al. 2003). However, recent research by Ansel et al. (2015) indicates that, compared to other, similar, measures of CU traits, the APSD is equally adequate.

The current study has multiple strengths. First, the CSDD is one of the longest running prospective longitudinal studies in existence that surveys a community sample and investigates criminality. Second, the data collected is comprehensive and was gathered from multiple different sources. Third, the study has allowed for the longest investigation to date of adult outcomes of adolescent psychopathic traits. Fourth and finally, the attrition is very low.

Conclusion

Adolescent psychopathic traits are useful intervention targets as they predict offending outcomes in adulthood and middle age, but whether the field should focus mainly on CU traits or a more comprehensive construct including GM and DI needs be resolved for the field of child and adolescent psychopathy to flourish and develop. The current study supports Salekin’s (2016a, b, 2017) notion that a more multidimensional approach is the way forward. The results indicate that high CU/high GM and high CU/high DI are more clinically impaired groups than those who are high on CU traits alone.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association.

Andershed, H., Colins, O. F., Salekin, R. T., Lordos, A., Kyranides, M., Fanti, K. A. (2018). Callous-unemotional traits only versus the multidimensional psychopathy construct as predictors of various antisocial outcomes during early adolescence. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(1), 16-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9659-5.

Ansel, L. L., Barry, C. T., Gillen, C. T. A., & Herrington, L. L. (2015). An analysis of four self-report measures of adolescent callous-unemotional traits: Exploring unique prediction of delinquency, aggression, and conduct problems. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37, 207–216.

Auty, K. M., Farrington, D. P., & Coid, J. W. (2015). Intergenerational transmission of psychopathy and mediation via psychosocial risk factors. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 206, 26–31.

Barry, C. T., Frick, P. J., DeShazo, T. M., McCoy, M. G., Ellis, M., & Loney, B. R. (2000). The importance of callous-unemotional traits for extending the concept of psychopathy to children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 335–340.

Bergstrøm, H., Forth, A. E., & Farrington, D. P. (2016). The psychopath: Continuity or change? Stability of psychopathic traits and predictors of stability. In A. Kapardis & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), The psychology of crime, policing and courts (pp. 94–115). Abingdon: Routledge.

Blais, J., Solodukhin, E., & Forth, A. E. (2014). A meta-analysis exploring the relationship between psychopathy and instrumental versus reactive violence. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 41, 797–821.

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1997). Statistics note. Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ, 314, 572.

Byrd, A. L., Hawes, S. W., Loeber, R., & Pardini, D. A. (2016). Interpersonal callousness from childhood to adolescence: developmental trajectories and early risk factors. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, online first. 1‑16

Christian, R. E., Frick, P. J., Hill, N. L., Tyler, L., & Frazer, D. R. (1997). Psychopathy and conduct problems in children: II. Implications for suptyping children with conduct problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child amd Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 233–241.

Cleckley, H. (1941/1988). The mask of sanity: An attempt to clarify some issues about the so-called psychopathic personality (5th ed.). Atlanta: Emily Cleckley.

Colins, O. F., & Vermeiren, R. R. J. (2013). The usefulness of DSM-IV and DSM-5 conduct disorder subtyping in detained adolescents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201, 736–743.

Colins, O. F., Andershed, A., Hawes, S. W., Bijttebier, P., & Pardini, D. A. (2016a). Psychometric properties of the original and short form of the inventory of callous-unemotional traits in detained female adolescents. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47, 679–690.

Colins, O. F., Fanti, K. A., Larsson, H., & Andershed, H. (2016b). Psychopathic traits in early childhood: further validation of the child problematic traits inventory. Assessment, 24, 602–614.

Colins, O. F., Fanti, K. A., Andershed, H., Mulder, E., Salekin, R. T., Blokland, A., & Vermeiren, R. R. J. M. (2017). Psychometric properties and prognostic usefulness of the youth psychopathic traits inventory (YPI) as a component of a clinical protocol for detained youth: A multiethnic examination. Psychological Assessment, 29, 740–753.

Dadds, M. R., Fraser, J., Frost, A., & Hawes, D. J. (2005). Disentangling the underlying dimensions of psychopathy and conduct problems in childhood: A community study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 400–410.

Douglas, K. S., Epstein, M. E., & Poythress, N. G. (2008). Criminal recidivism among juvenile offenders: Testing the incremental and predictive validity of three measures of psychopathic features. Law and Human Behavior, 32, 423–438.

Edens, J. F., Campbell, J. S., & Weir, J. M. (2007). Youth psychopathy and criminal Recidivism: a meta-analysis of the psychopathy checklist measures. Law and Human Behavior, 31, 53–75.

Essau, C. A., Sasagawa, S., & Frick, P. J. (2006). Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment, 13, 454–469.

Falkenbach, D. M., Poythress, N. G., & Heide, K. M. (2003). Psychopathic features in a juvenile diversion population: reliability and predictive validity of two self-report measures. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 21, 787–805.

Fanti, K. A., Kyranides, M. N., Georgiou, G., Petridou, M., Colins, O. F., Tuvblad, C., & Andershed, H. (2017). Callous-unemotional, impulsive-irresponsible, and grandiose-manipulative traits: distinct associations with heart rate, skin conductance, and startle response to violent and erotic scenes. Psychophysiology, online first, 54, 663–672.

Farrington, D. P. (1995). The development of offending and antisocial behaviour from childhood: key findings from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36, 929–964.

Farrington, D. P. (2003). Key results from the first 40 years of the Cambridge study in delinquent development. In T. P. Thornberry & M. D. Krohn (Eds.), Taking stock of delinquency: An overview of findings from contemporary longitudinal studies (pp. 137–183). New York: Kluwer/Plenum.

Farrington, D. P. (2005). The importance of child and adolescent psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Child and Adolescent Psychopathy, 33, 489–497.

Farrington, D. P., & Bergstrøm, H. (in press). Social origins of psychopathy. In A. R. Felthous & H. Sass (Eds.), International handbook on psychopathic disorders and the law, vol. 1: diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Farrington, D. P., & Loeber, R. (2000). Some benefits of dichotomization in psychiatric and criminological research. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 10, 100–122.

Farrington, D. P., Coid, J. W., Harnett, L., Jolliffe, D., Soteriou, N., Turner, R. E., & West, D. J. (2006). Criminal careers up to age 50 and life success up to age 48: New findings from the Cambridge study in delinquent development (2nd ed.). London: Home Office (Research Study 299).

Farrington, D. P., Coid, J. W., & West, D. J. (2009). The development of offending from age 8 to age 50: recent results from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Monatsschrift fur Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform (Journal of Criminology and Penal Reform), 92, 160–173.

Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., & Jennings, W. G. (2013). Offending from childhood to late middle age: Recent results from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. New York: Springer.

Fink, B. C., Tant, A. S., Tremba, K., & Kiehl, K. A. (2012). Assessment of psychopathic traits in an incarcerated adolescent sample: a methodological comparison. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 971–986.

Fontaine, N. M. G., McCrory, E. J. P., Boivin, M., Moffitt, T. E., & Viding, E. (2011). Predictors and outcomes of joint trajectories of callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 730–742.

Forth, A. E., Kosson, D., & Hare, R. (2003). The Hare psychopathy checklist: Youth version. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Frick, P. J. (2016). Current research on conduct disorder in children and adolescents. South Africa Journal of Psychology, 46, 160–174.

Frick, P. J., & Hare, R. D. (2001). Antisocial process screening device: APSD. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Frick, P. J., & White, S. F. (2008). Research review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 359–375.

Frick, P. J., Cornell, A. H., Barry, C. T., Bodin, S. D., & Dane, H. E. (2003). Callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in the prediction of conduct problem severity, aggression, and self-report of delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31, 457–470.

Frick, P. J., Ray, J. V., Thornton, L. C., & Kahn, R. E. (2014). Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 1–57.

Frogner, L., Gibson, C. L., Andershed, A-K., & Andershed, H. (2016). Childhood psychopathic personality and callous–unemotional traits in the prediction of conduct problems. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,88(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000205.

Frogner, L., Andershed, A-K., & Andershed, H. (2018). Psychopathic personality works better than CU traits for predicting fearlessness and ADHD symptoms among children with conduct problems. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(1), 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9651-0.

Gadermann, A. M., Guhn, M., & Zumbo, B. D. (2012). Estimating ordinal reliability for Likert-type and ordinal item response data: a conceptual, empirical, and practical guide. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 17, 1–13.

Gillen, C. T. A., Barry, C. T., & Bater, L. R. (2016). Anxiety symptoms and coping motives: examining a potential path to substance use-related problems in adolescents with psychopathic traits. Substance Use and Misuse, 51, 1920–1929.

Gretton, H. M., Hare, R. D., & Catchpole, R. E. H. (2004). Psychopathy and offending from adolescence to adulthood: a 10-year follow up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 636–645.

Hare, R. D. (1993). Without conscience: The disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hare, R. D., & Neumann, C. S. (2005). The PCL-R assessment of psychopathy. Development, structural properties, and new directions. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy (pp. 58–77). New York: Guilford Press.

Hawes, S. W., Byrd, A. L., Waller, R., Lynam, D. R., & Pardini, D. A. (2016). Late childhood interpersonal callousness and conduct problem trajectories interact to predict adult psychopathy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12598.

Hemphill, J. F., Hart, S. D., & Hare, R. D. (1994). Psychopathy and substance use. Journal of Personality Disorders, 8, 169–180.

Kahn, R. E., Frick, P. J., Youngstrom, E., Findling, R. L., & Yongstrom, J. K. (2012). The effects of including a callous-unemotional specifier for the diagnosis of conduct disorder. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 271–282.

Kennealy, P. J., Skeem, J. L., Walters, G. D., & Camp, J. (2010). Do core interpersonal and affective traits of PCL-R psychopathy interact with antisocial behavior and disinhibition to predict violence? Psychological Assessment, 22, 569–580.

Kiehl, K. A., & Hoffman, M. B. (2011). The criminal psychopath: History, neuroscience, treatment, and economics. Jurimetrics, 51, 355–397.

Lee, Z. V., Hart, S. D., & Corrado, R. R. (2003). The validity of the antisocial process screening device as a self-report measure of psychopathy in adolescent offenders. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 21, 771–786.

Lee-Rowland, L. M., Barry, C. T., Gillen, C. T. A., & Hansen, L. K. (2017). How do different dimensions of adolescent narcissism impact the relation between callous-unemotional traits and self-reported aggression? Aggressive Behavior, 43, 14–25.

Mailloux, D. L., Forth, A. E., & Kroner, D. G. (1997). Psychopathy and substance use in adolescent male offenders. Psychological Reports, 81, 529–530.

McMahon, R. J., Witkiewitz, K., & Kotler, J. S. (2010). Predictive validity of callous-unemotional traits measured in early adolescence with respect to multiple antisocial outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 752–263.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Life-course persistent and adolescent limited antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Munoz, L. C., & Frick, P. J. (2007). The reliability, stability, and predictive utility of the self-report version of the antisocial process screening device. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48, 299–312.

Salekin, R. T. (2008). Psychopathy and recidivism from mid-adolescence to young adulthood: Cumulating legal problems and limiting life opportunities. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 386–395.

Salekin, R. T. (2016a). Psychopathy in childhood: Why should we care about grandiose manipulative and daring-impulsive traits? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209, 189–191.

Salekin, R. T. (2016b). Psychopathy in childhood: Toward better informing the DSM-5 and ICD-11 conduct disorder specifiers. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7, 180–191.

Salekin, R. T. (2017). Research review: what do we know about psychopathic traits in children? The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(11), 1180–1200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12738.

Salekin, R. T., & Lynam, D. R. (2010). Child and adolescent psychopathy: An introduction. In R. T. Salekin & D. R. Lynam (Eds.), Handbook of child and adolescent psychopathy (pp. 1–12). New York: Thje Guilford Press.

Salihovic, S., & Stattin, H. (2016). Psychopathic traits and delinquency trajectories in adolescence. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 39, 15–24.

Scheepers, F. E., Buitelaar, J. K., & Matthys, W. (2011). Conduct disorder and the specifier callous and unemotional traits in the DSM-5. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 20, 89–93.

Seagrave, D., & Grisso, T. (2002). Adolescent development and the measurement of juvenile psychopathy. Law and Human Behavior, 26, 219–239.

Sijtsma, K. (2009). On the use, misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika, 74, 107–120.

Smith, S. S., & Newman, J. P. (1990). Alcohol and drug abuse-dependence disorders in psychopathic and nonpsychopathic criminal offenders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 430–439.

Spurk, D., Keller, A. C., & Hirschi, A. (2015). Do bad guys get ahead or fall behind? Relationships of the dark triad of personality with objective and subjective career success. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7, 113–121.

Ullrich, S., Farrington, D. P., & Coid, J. W. (2008). Psychopathic personality traits and life success. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1162–1171.

Van Geel, M., Toprak, F., Goemans, A., Zwaanswijk, W, & Vedder, P. (2016). Are youth psychopathic traits related to bullying? Meta-analyses on callous-unemotional traits, narcissism, and impulsivity. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 48(5), 768–777.

Van Ginkel, J. R., van der Ark, L. A., & Sijtsma, K. (2007). Multiple imputation of item scores in test and questionnaire data, and influence on psychometric results. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 387–414.

Verona, E., Sprague, J., & Javdani, S. (2012). Gender and factor-level interactions in psychopathy: Implications for self-directed violence risk and borderline personality disorder symptoms. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3, 247–262.

Vitacco, M. J., Rogers, R., & Neumann, C. S. (2003). The Antisocial Process Screening Device. An examination of its construct and criterion-related validity. Assessment, 10, 143–150.

Waller, R., Gardner, F., & Hyde, L. W. (2013). What are the associations between parenting, callous-unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 593–608.

Waller, R., Hyde, L. W., Grabell, A. S., Alves, M. L., & Olson, S. L. (2015). Differential associations of early callous-unemotional, oppositional, and ADHD behaviors: Multiple domains within early-starting conduct problems. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 657–666.

Waller, R., Baskin-Sommers, A. R., & Hyde, L. W. (2016). Examining predictors of callous unemotional traits trajectories across adolescence among high-risk males. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1102070.

Walsh, Z., & Kosson, D. S. (2008). Psychopathy and violence: the importance of factor level interactions. Psychological Assessment, 20, 114–120.

Funding

The CSDD has been funded mainly by the UK Home Office and the UK Department of Health, UK National Programme on Forensic Mental Health. No conflict of interest reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for the interviews was granted by the Institute of Psychiatry, London University ethics committee. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Authors Henriette Bergstrøm and David P. Farrington declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bergstrøm, H., Farrington, D.P. Grandiose-Manipulative, Callous-Unemotional, and Daring-Impulsive: the Prediction of Psychopathic Traits in Adolescence and their Outcomes in Adulthood. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 40, 149–158 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9674-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9674-6