Abstract

Examined the age of onset of ADHD symptoms and subtypes using parent ratings of a large sample of elementary school students. Results showed: (1) in children with ADHD-combined type, hyperactive-impulsive symptoms emerged at younger ages than inattention symptoms; (2) about one-fifth of children who met symptom count and impairment criteria for ADHD did not meet the age of onset criterion; (3) Children who did not meet the age of onset criterion consisted primarily of children with inattention problems; and (4) children who did not meet the age of onset criterion had more impaired parent-child relationships, self-esteem, family functioning, and higher overall impairment ratings than children who did meet the criterion. These results raise questions about the validity of the age of onset criterion for ADHD as formulated in DSM-IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a childhood disorder characterized by persistent, impairing, and developmentally inappropriate behaviors of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) provides several criteria for clinically assessing and diagnosing the disorder, including a requirement that symptoms were present and caused impairment before age seven. Although there is an ever-increasing body of literature on the validity of the DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD, relatively little research has examined the validity of the age of onset criterion.

Theoretical arguments have been made both for and against the inclusion of an age of onset criterion (Barkley & Biederman, 1997). The main argument in support of the age of onset criterion for ADHD is that it is consistent with the predominant view that ADHD is a disorder of childhood and that it helps avoid misclassifying children as having ADHD when in reality their behavior problems are secondary to school failure due to learning disabilities, aggression, or other similar difficulties. In contrast, opponents of the age of onset criterion point to recent longitudinal studies that show ADHD is not simply a disorder of childhood but instead persists over the course of development (Willoughby, 2003). Likewise, opponents note that requiring an early age of onset may result in the misdiagnosis of children whose symptoms of ADHD do not become apparent until they begin attending school or until after school becomes challenging. These children may not be evaluated until they are past the age limit set by the age of onset criterion, even though the disorder may have been present earlier. Thus, requiring symptom onset prior to age seven may risk misdiagnosing these children.

Results of empirical studies examining the age of onset criterion have also been mixed. In support of including the age of onset criterion is research showing that children with an earlier age of onset of ADHD symptoms have higher rates of comorbidity, more pervasive ADHD symptoms, and more serious deficits on measures of IQ, reading, and perceptual motor skills (McGee, Williams, & Feehan, 1992). Furthermore, children with an early onset of ADHD have more severe and impairing clinical outcomes later in life relative to children with a later onset of ADHD (Willoughby, Curran, Costello, & Angold, 2000). In contrast, data from the DSM-IV field trials for ADHD showed that children who met DSM-IV symptom count and impairment criteria for ADHD but not the age of onset criterion did not differ from those met symptom count, impairment and the age of onset criteria, with both groups evidencing more impairment than typically developing children (Applegate et al., 1997). This same study showed that the DSM-IV age of onset criterion ``reduced the accuracy of identification of currently impaired cases of ADHD and reduced the agreement with clinician's judgments'' (Applegate et al., 1997, p. 1211). Thus, both theoretical arguments and empirical data present a mixed picture as to whether the age of onset criterion increases the diagnostic validity of ADHD.

A related question is whether the age of onset of ADHD differs as a function of subtype. The DSM-IV currently defines three subtypes of ADHD: ADHD combined type (ADHD/C), ADHD predominately inattentive type (ADHD/IA), and ADHD predominately hyperactive/impulsive type (ADHD/HI). Relatively few studies have directly examined this issue, but this limited research shows that children with the inattentive type of ADHD have a significantly older age of onset for ADHD than do children with the hyperactive/impulsive or combined subtypes (Applegate et al., 1997; Faraone, Biederman, Weber, & Russell, 1998; Willoughby et al., 2000). While these findings are consistent, the dearth of studies in this area suggests further research is needed. Especially informative would be research examining normative samples of children, rather than clinical samples, since age of onset may be related to symptom severity, which may in turn impact whether the individual seeks treatment. Community samples do not have these shortcomings, making examination of age of onset in such samples highly informative.

The purpose of this study was to examine the age of onset criterion, as defined by DSM-IV, for ADHD subtypes within a large community sample of elementary school students. Parent ratings of problem behavior were used to investigate whether the age of symptom onset differed among the subtypes of ADHD and whether the onset of ADHD was related to differences in severity levels of problem behavior and functioning. Two hypotheses were formulated. First, it was hypothesized that children with the inattentive subtype of ADHD would have a significantly later age of onset than children with other subtypes of ADHD. This hypothesis was based on previous research showing this pattern among children with ADHD (Applegate et al., 1997; Faraone et al., 1998; Willoughby et al., 2000), Second, it was hypothesized that children with an earlier onset of ADHD would show more problematic levels of behavior and functioning as compared to children with a later onset of ADHD. This hypothesis was based on research showing that children with early onset conduct problems – a behavior high related to ADHD – have more severe and impairing problems compared to children with a later onset of conduct problems (Moffitt, 1990).

Method

Participants

Participants were parents of 835 children who were students in one of seven elementary schools in Eastern Canada during the 1999–2000 school year. Students ranged in age from five to 12 (M = 8.06; SD = 1.90) and consisted of 428 boys (51%) and 407 girls (49%). The majority of children lived with two parents (72.6%) and had one or two siblings (70.9%). Estimated Hollingshead (1975) four-factor socio-economic status (SES) scores ranged from 14 to 66 (M = 36.13; SD = 12.65). Ethnic and racial information of participants was not collected (at the request of the participating school board), but the schools serve communities that are over 95% Caucasian (Nova Scotia Department of Finance, 2003).

Procedure

Data were collected as part of evaluating a school intervention program (Waschbusch, Pelham, Massetti, & Northern Partners In Action for Children and Youth, in press). All ratings used in this study were completed at the start of the school year, prior to the implementation of the intervention. Ratings were gathered by sending home (via students) a packet of information that included a description of the intervention and a packet of behavior rating scales. Enclosed instructions asked each parent (mothers and fathers) to independently complete a rating scale for every student in their household. Parents of 53% of students returned ratings. These procedures were approved by a university human ethics board, by the participating school district, and by the administrators in the participating schools.

Measures

Assessment of disruptive symptoms DSM-IV (ADS-IV)

The ADS-IV is a rating scale designed to measure ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) in elementary school children (Waschbusch, Sparkes, & Northern Region Partners In Action for Children and Youth, 2003). A parent-completed version and a teacher-completed version have been developed for the ADS-IV. The current study used the parent version. The majority of items on the ADS-IV are symptoms of ADHD and ODD taken directly from the DSM-IV, with minor wording changes to make them more concise and appropriate for a rating scale format. Specifically, the word ``often'' was removed from all symptoms, as others have done (Burns et al., 1997), and some items were simplified (e.g., ``Often blurts out answers before questions have been completed'' was changed to ``Blurts out answers before questions have been finished''). Each symptom is rated on a 0 (``much less than other children'') to 4 (``much more than other children'') Likert scale to indicate the extent to which the child expresses the symptom relative to others of the same age and gender. After each group of symptoms (i.e., ADHD-inattention, ADHD-hyperactive(impulsive, and ODD), the ADS-IV includes items to assess the extent to which the symptoms cause impairment and (on the parent version) the age of onset of the symptoms. Impairment is assessed using Likert scales to evaluate the degree to which symptoms cause the child problems at home, at school and other places, with each location evaluated separately. Possible responses to the impairment items range from 0 (``no problems'') to 4 (``very severe problems''). Age of onset is assessed with an item phrased ``how old was this child when he(she started behaving this way?'' followed by blank for parents to fill in an age. As recommended (Bird, Gould, & Staghezza, 1992; Piacentini, Cohen, & Cohen, 1992), responses to the symptom and impairment items were combined across mothers and fathers by taking the highest (most severe) rating. Mother and father responses to the age of onset items were combined by taking the oldest reported age.

The factor structure, reliability and validity of the ADS-IV has been supported (Waschbusch et al., 2003). Internal consistency (alpha) coefficients for parent ratings ranged from .92 to .97 and seven month test retest reliability coefficients ranged from .67 to .82. Similarly, the ADS-IV has significant criterion validity with the IOWA Connors (Pelham, Milich, Murphy, & Murphy, 1989), with convergent validity correlations ranging from .54 to .65 and with convergent validity correlations significantly higher than discriminant validity correlations. In addition, three experts on the assessment of ADHD and ODD rated the ADS-IV as having 100% correspondence with the symptoms of ADHD and ODD as listed in the DSM-IV, thereby supporting the criterion validity of the ADS-IV.

Children's impairment rating scale (CIRS)

The CIRS is designed to evaluate the child's current level of impairment in developmentally important areas (Fabiano et al., in press; Pelham et al., 1996). Seven areas were rated: (1) peer relationships, (2) getting along with parents, (3) getting along with siblings, (4) school performance, (5) family relationships, (6) self esteem, and (7) overall functioning. The reliability and validity of the CIRS has been supported in several samples (Fabiano et al., in preparation). For example, in one sample, one-year test-retest reliability correlations for parent ratings on the CIRS ranged from .54 to .79 and inter-rater (parent and teacher) reliability correlations ranged from .47 to .64.(Lahey et al., 1998). Similarly, criterion validity of the CIRS was supported by finding significant correlations with the Children's Global Assessment Scale (Setterberg, Bird, & Gould, 1992), with convergent validity correlations ranging from −.55 to −.79.

In the present study, items on the CIRS were changed from visual-analogue scales to Likert ratings, with possible responses ranging from 0 (``no need for treatment'') to 4 (``very severe need for treatment''). Likert ratings, rather than a visual-analogue scale, were used to facilitate scoring and data entry (due to the large sample size), to keep items consistent with all other rating scales, and to allow for administration of items over the telephone in an unrelated study. Comparison of the Likert format to the original format shows that they are highly and significantly associated in both clinical and community samples (rs ≫.72).

Diagnostic procedure

Using parent ratings on the ADS-IV, children were assigned to the ADHD group as follows: (a) mother and father ratings were combined by taking the maximum score on an item-by-item basis; (b) symptom counts were computed by counting the number of items rated three or four, indicating that the symptom is present in the target child more or much more than other children. Separate counts were computed for inattention symptoms and for hyperactive/impulsive symptoms; (c) impairment from symptoms was evaluated, with ratings of two (indicating that the symptoms cause the target child ``moderate problems'') or higher considered significant impairment; and (d) DSM-IV criteria were applied to determine whether ADHD was met, and if so, what subtype. For instance, children were assigned to the ADHD-inattentive type group if they were rated as having six or more symptoms of inattention but having less than six symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity, and if they were rated as having at least moderate impairment from inattention symptoms. Applying these criteria identified 43 children (5.1%) with ADHD/IA, 21 (2.5%) with ADHD/HI, and 30 (3.6%) with ADHD/C. The remaining 741 children (88.7%) were classified as controls.

The validity of these diagnostic procedures has been supported in research comparing diagnostic groups formed using ADS-IV with diagnostic groups formed using the Disruptive Behavior Disorder Rating Scale (Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, 1992) and with groups formed using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children – DSM-IV version (NIMH-DISC Editorial Board, 1999). Summarizing across one clinical sample (Waschbusch, 2004) and one community sample (Waschbusch, King, & Northern Partners in Action for Children and Youth, 2006), the sensitivity of the ADS-IV for diagnosing children in ADHD subtypes (None vs. ADHD-inattentive vs. ADHD-hyperactive/impulsive vs. ADHD-combined) ranged from 69.05 to 85.26 (M = 76.58, SD = 6.85), specificity ranged from 65.31 to 96.67 (M = 83.79, SD = 13.21), and the overall agreement ranged from 79.00 to 88.18 (M = 81.97, SD = 4.19). Agreement was higher when ADHD was defined after collapsing across subtypes (sensitivity: M = 85.40, SD = 6.28, range (78.38 to 92.36; specificity: M = 91.02, SD = 14.95, range (68.85 to 100; overall agreement: M = 90.37, SD = 4.26, range (85.37 to 95.45). Similar findings emerged for ratings of oppositional defiant disorder.

Results

Demographics

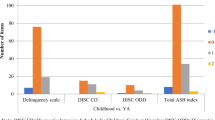

The ADHD subtype groups were compared to each other and to controls on demographic and rating scale measures. Results are summarized in Table 1. The average age at assessment differed across groups such that ADHD/IA children were significantly older than controls and older than ADHD/HI children. As expected, there were more boys than girls among children with ADHD, but an equal gender ratio among children without ADHD. Socioeconomic status (SES) of subtypes did not differ. Comparison of number of ADHD symptoms endorsed by parents showed that, as expected, ADHD/IA and ADHD/C had more inattention symptoms than other groups, and that ADHD/HI and ADHD/C groups had more hyperactive(impulsive symptoms than other groups. Comparison of groups on oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) symptoms showed that children with ADHD/C had the largest number of ODD symptoms. ADHD/IA and ADHD/HI groups did not differ from each other but had more ODD symptoms than controls.

Age of onset

Missing information

Parents of 35 of the 43 ADHD/IA children (81%) provided data on inattention age of onset, parents of 15 of the 21 ADHD/HI children (71%) provided data for hyperactive/impulsive age of onset, and parents of 27 of the 30 ADHD/C children (90%) provided data on both inattention and hyperactive/impulsive symptom age of onset. Children with ADHD whose parents provided age of onset information (n = 77) were compared to ADHD children who did not have this information (n = 17) using one-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests. There were no significant differences on any measure, including age at assessment, SES, ratio of boys to girls, number inattention or hyperactive/mpulsive symptoms, impairment from hyperactive/impulsive or inattention symptoms, or any of the seven items on the Children's Impairment Rating Scale.

Reliability

Reliability of parent reported age of onset was examined by computing an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between mother ratings and father ratings. A two-way, mixed effects ICC model was used, with rater as a random factor and measures as a fixed factor and with measures averaged over raters. For these analyses, only children who met criteria for ADHD and who had both mother and father data were used (n = 24). Results showed that the mother-reported age of onset was significantly associated with father reported age of onset for both hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (r = .70, p = .01) and for inattentive symptoms (r = .95, p = .001).

ADHD subtype comparisons

Subtype differences in age of onset were examined in three ways. First, age of onset for inattention symptoms was compared for ADHD/IA and ADHD/C children using a one-way ANOVA. Results showed no difference between the groups (ADHD/IA: M = 5.69, SD = 1.89, Range = 0 to 11; ADHD/C: M = 5.31, SD = 2.00, Range = 1 to 9). Second, the same strategy was used to compare onset of hyperactive/impulsive symptoms for ADHD/HI and ADHD/C children. These groups also did not differ (ADHD/HI: M = 3.53, SD = 1.46, Range = 1 to 6; ADHD/C: M = 4.70, SD = 2.16, Range (2 to 10). Third, onset of inattention and hyperactive(impulsive symptoms was compared within the ADHD(C group using a paired samples t-test. There was a significant difference in age of onset of the two types of symptoms, t(26) = −2.37, p < .05, with hyperactive(impulsive symptoms emerging at a significantly younger age than inattentive symptoms.

Validity

To examine the validity of the age of onset criterion, children with ADHD who met the age of onset criterion (ADHD-met, n = 63) were compared to children with ADHD who did not meet the age of onset criterion (ADHD-not, n = 14). These groups were formed after collapsing across subtypes of ADHD. To test whether collapsing subtypes was warranted, subtypes were compared using a 2 (Age of Onset Group: ADHD-met vs. ADHD-not) × 3 (ADHD subtype: ADHD/IA vs. ADHD/HI vs. ADHD/C) chi-square. The chi-square was not significant, indicating that children who did and did not meet the age of onset criterion were equally likely to occur in all three subtypes of ADHD. The number and percent of children within each ADHD subtype who met the age of onset criterion were: ADHD/IA = 26 (74.3%); ADHD/HI = 15 (100%); ADHD/C = 22 (81.5%). To further test the grouping procedure, one-way ANOVAs were computed comparing the ADHD-met and ADHD-not groups on age of onset data. Results showed that children who did not meet the age of onset criterion had a significantly older age of onset for both inattention, F(1, 73) = 78.38, p < .001, and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, F(1, 67) = 57.13, p < .001, thereby validating the grouping procedure and the decision to combine ADHD subtypes.

Next, the ADHD-met and ADHD-not groups were compared on aspects of ADHD other than age of onset using a series of one-way ANOVAs, with symptom counts and with impairment associated with ADHD symptoms as dependent measures. Groups did not differ significantly on number of inattention symptoms (ADHD-met: M = 6.75, SD = 2.26, ADHD-not: M = 7.93, SD = 1.27), number of hyperactive/impulsive symptoms (ADHD-met: M = 5.48, SD = 2.73, ADHD-not: M = 4.64, SD = 2.44), impairment from inattention (ADHD-met: M = 1.89, SD = 1.05, ADHD-not: M = 2.00, SD = 0.88), or impairment from hyperactivity/impulsivity (ADHD-met: M = 1.83, SD = 1.07, ADHD-not: M = 2.07, SD = 1.14).

Finally, the ADHD-met and ADHD-not groups were compared to each other and to children without ADHD (Controls; n = 679) on other measures of impairment. Results (see Table 2) showed that both groups of children with ADHD were significantly more impaired than non-ADHD children on every measure. More central to this study, results also showed that the ADHD children who did not meet the age of onset criterion were rated as having significantly more impaired parent-child relationships, self-esteem, family functioning and as having significantly more overall impairment as compared to ADHD children who met the age of onset criterion (see Table 2).

Discussion

This study examined the age of onset criterion for ADHD using a community sample of elementary school aged children. A number of significant findings emerged. First, results showed that, in children with ADHD/C, hyperactive/impulsive symptoms had an earlier age of onset than inattention symptoms (see Table 1). These results are consistent with other studies (Lahey et al., 1994; Loeber, Green, Lahey, Christ, & Frick, 1992). One interpretation of this research is that ADHD/HI may be a developmental precursor to ADHD/C (Carlson, Shin, & Booth, 1999; Lahey et al., 1998). That is, it is possible that children who ultimately receive a diagnosis of ADHD/C develop hyperactive-impulsive symptoms at a young age, leading to a diagnosis of ADHD/HI, and subsequently develop inattentive symptoms, leading to a diagnosis of ADHD/C. Recent research supports this interpretation (Lahey, Pelham, Loney, Lee, & Willcutt, 2005).

Second, the study compared whether subtypes of ADHD were more or less likely than each other to meet the age of onset criterion. Although the groups did not differ significantly, it is noteworthy that none of the ADHD/HI group failed to meet the age of onset criterion, whereas a sizable portion of children in the ADHD/IA (25.7%) and ADHD/C (18.5%) groups did fail to meet the age of onset criterion. This pattern lends further credence to the notion that inattention problems tend to be identified at older ages as compared to the other symptoms of ADHD; however, the reasons for this pattern are unknown. It is possible that attention problems are present at earlier ages but go undetected until school entry, when many children first encounter tasks that challenge their ability to pay attention. Alternatively, attention problems may not actually present until later in childhood. It would be useful to tease apart these possibilities empirically using longitudinal research that starts early in life and includes both objective measures of attention (e.g., performance tasks) and subjective reports of attention (e.g., parent and teacher ratings).

Third, comparisons of children who did and did not meet the age of onset criterion showed that the groups did not differ on the number of ADHD symptoms present or on impairment resulting from symptoms, but they did differ on some measures of impairment (see Table 2). Surprisingly, in areas where differences did emerge (parent-child relationships, self esteem, family relationships, and overall impairment) children who did not meet the age of onset criterion were rated as more impaired than children who did meet the criterion. These findings raise questions about the validity of the age of onset criterion as specified in DSM-IV. If DSM-IV diagnostic criteria were strictly applied, these children would not be assigned an ADHD diagnosis (or would be assigned a ``not otherwise specified'' diagnosis), thereby excluding a sizeable portion of the most seriously impaired children with ADHD. To the extent that diagnosis is related to treatment access and conducting accurate research, this is a serious problem.

The finding that children with later onset of problems were more impaired than children with earlier onset of problems is opposite to what is often found in studies examining conduct problems in children (Loeber & Keenan, 1994; Moffitt, 1993) as well as to some other studies of ADHD (McGee et al., 1992; Willoughby et al., 2000), which have found that children with earlier onset of behavior problems have significantly greater impairment as compared to children with later onset of behavior problems. One explanation for these different patterns of results is that the measure of impairment in the present study was markedly different from measures of impairment that have been used in past research. Specifically, the present study found differences between groups on relationship measures, on a measure of the child's self esteem, and on an overall impairment item. In contrast, previous research on age of onset found differences on academic and behavioral measures. It may be, then, that the pattern of results differs across studies because different aspects of impairment were examined. In fact, one interpretation of the results from this study is that the ``late onset'' group in this study (i.e., the group that did not meet the age of onset criterion) consisted largely of children with symptoms of depression. Indeed, low self-esteem, problematic relationships with parents, and problematic family functioning are some of the hallmarks of depression in children (Kovacs & Devlin, 1998), and research has demonstrated that children with ADHD(IA – and especially those with sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms such as daydreaming, disorganization, and lethargy – are more likely to have symptoms of depression than are other children (Carlson & Miranda, 2002; Carlson et al., 1999). If this interpretation is correct, one possible implication is that the inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity problems exhibited by the ``late onset'' group may result from affective or other adjustment problems, rather than from ADHD. This would suggest it is not the age of onset criterion that is not valid; rather, it is the diagnosis of ADHD in the ``late onset'' group that is not valid. Unfortunately, no measures of internalizing symptoms were administered in this study, making it impossible to evaluate this possibility more directly. Further research into this hypothesis would provide useful information.

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, this study relied on cross-sectional data rather than longitudinal data. Developmental questions such as those posed by the current investigation are ideally examined using longitudinal data. However, such data are difficult, expensive, and time consuming to gather. Given these considerations, cross-sectional research can be an important first step. Even so, by relying on cross-sectional data it remains unclear whether the age of onset findings reflect ``true'' differences or instead reflect differences in parental ability to recall symptoms. Second, the age of onset was measured globally, rather than on a symptom-by-symptom basis. Using a global measure made it feasible to evaluate age of onset with a rating scale administered to a large sample of children. It remains unclear whether symptom-by-symptom approaches to evaluating age of onset are psychometrically superior to the global measure used in this study, but it is clear that using a global measure makes it difficult to precisely examine the developmental sequence of ADHD behaviors, as others have done (Loeber et al., 1992). Third, the vast majority of children in the sample were Caucasian. This reflected the community in which the study was conducted, but suggests that caution is warranted in generalizing the findings to more ethnically diverse samples. Finally, a limitation of the current study is that only about half (53%) of eligible parents returned rating scales, and not all of these completed the age of onset question used in this study. As such, the results can only be generalized to children whose parents are willing to complete and return rating scales similar to the ones administered.

In summary, this study examined age of onset in children with ADHD using a community sample of children in elementary school. Results showed that about one-fifth of children who meet symptom count and impairment criteria for ADHD in the present sample do not meet DSM-IV age of onset criteria, and that these children consisted of children with the inattentive and combined subtypes of ADHD. Further, children who did not meet the age of onset criterion did not differ from other children with ADHD on measures of the number of symptoms or the impairment resulting from symptoms, but they were rated as having greater impairment on self esteem, family relationships, parent-child relationships, and overall functioning. These results raise important questions regarding the validity of the DSM-IV defined age of onset criteria for diagnosing ADHD.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical manual of mental Disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, D.C.: Author.

Applegate, B., Lahey, B. B., Hart, E. L., Biederman, J., Hynd, G. W., Barkley, R. A., et al. (1997). Validity of the age-of-onset criterion for ADHD: A report from the DSM-IV field trials. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 1211–1221.

Barkley, R. A., & Biederman, J. (1997). Toward a broader definition of the age-of-onset criterion for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 1204–1210.

Bird, H. R., Gould, M. S., & Staghezza, B. M. (1992). Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 78–85.

Burns, G. L., Walsh, J. A., Patterson, D. R., Holte, C. S., Sommers-Flanagan, R., & Parker, C. M. (1997). Internal validity of the disruptive behavior disorder symptoms: Implications from parent ratings for a dimensional approach to symptom validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25, 307–319.

Carlson, C. L., & Miranda, M. (2002). Sluggish cognitive temp predicts a different pattern of impairment in the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, predominately inattentive type. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 123–129.

Carlson, C. L., Shin, M., & Booth, J. (1999). The case for DSM-IV subtypes in ADHD. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 5, 199–206.

Fabiano, G. A., Pelham, W. E., Waschbusch, D. A., Gnagy, E. M., Lahey, B. B., Chronis, A. M., et al. (in press). A practical impairment measure: Psychometric properties of the Impairment Rating Scale in samples of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology.

Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J., Weber, W., & Russell, R. L. (1998). Psychiatric, neuropsychological, and psycho-social features of DSM-IV subtypes of attention-deficit(hyperactivity disorder: Results form a clinically referred sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 185–193.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1975). Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University.

Kovacs, M., & Devlin, B. (1998). Internalizing disorders in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39, 47–63.

Lahey, B. B., Applegate, B., McBurnett, K., Biederman, J., Greenhill, L., Hynd, G. W., et al. (1994). DSM-IV field trials for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1673–1685.

Lahey, B. B., Pelham, W. E., Loney, J., Lee, S. S., & Willcutt, E. (2005). Instability of the DSM-IV subtypes of ADHD from preschool through elementary school. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 896–902.

Lahey, B. B., Pelham, W. E., Stein, M. A., Loney, J., Trapani, C., Nugent, K., et al. (1998). Validity of DSM-IV attention-deficit(hyperactivity disorder for younger children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 695–702.

Loeber, R., Green, S. M., Lahey, B. B., Christ, M. A. G., & Frick, P. J. (1992). Developmental sequences in the age of onset of the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 1, 21–41.

Loeber, R., & Keenan, K. (1994). Interaction between conduct disorder and its comorbid conditions: Effects of age and gender. Clinical Psychology Review, 14, 497–523.

McGee, R., Williams, S., & Feehan, M. (1992). Attention deficit disorder and age of onset of problem behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 20, 487–502.

Moffitt, T. E. (1990). Juvenile delinquency and attention deficit disorder: Boys' developmental trajectories from age 3 to age 15. Child Development, 61, 893–910.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescent-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

NIMH-DISC Editorial Board. (1999). The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. New York: Columbia University.

Nova Scotia Department of Finance. (2003). 2001 Census of Canada: Nova Scotia Perspective.

Pelham, W. E., Gnagy, E. M., Greenslade, K. E., & Milich, R. (1992). Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 210–218.

Pelham, W. E., Gnagy, E. M., Waschbusch, D. A., Willoughby, M., Palmer, A., Whichard, M., et al. (1996). A practical impairment scale for childhood disorders: Normative data and an application to ADHD. Paper presented at the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, Santa Monica, CA.

Pelham, W. E., Milich, R., Murphy, D. A., & Murphy, H. A. (1989). Normative data on the IOWA Conners teacher rating scale. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18, 259–262.

Piacentini, J. C., Cohen, P., & Cohen, J. (1992). Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: Are complex algorithms better than simple ones? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 20, 51–63.

Setterberg, S., Bird, H., & Gould, M. (1992). Parent and interviewer version of the Children's Global Assessment Scale. New York: Columbia University.

Waschbusch, D. A. (2004). How do children with ADHD think in social situations and what does it tell us about treatment? Paper presented at the Center for Children and Families, University at Buffalo.

Waschbusch, D. A., King, S., & Northern Partners in Action for Children and Youth (2006). Should sex-specific norms be used to assess Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD)? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 179–185.

Waschbusch, D. A., Pelham, W. E., Massetti, G. M., & Northern Partners in Action for Children and Youth (2005). The Behavior Education Support and Treatment (BEST) school intervention program: Pilot project data examining school-wide, targeted-school, and targeted-home approaches. Journal of Attention Disorders, 9(1), 313–322.

Waschbusch, D. A., Sparkes, S. J., & Northern Region Partners In Action for Children and Youth. (2003). Rating scale assessment of attention-deficit(hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) symptoms: Is there a normal distribution and does it matter? Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 21, 261–281.

Willoughby, M. T. (2003). Developmental course of ADHD symptomatology during the transition from childhood to adolescence: A review with recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,44, 88–106.

Willoughby, M. T., Curran, P. J., Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (2000). Implications of early versus late onset of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 1512–1519.

Acknowledgements

Northern Partners in Action for Children and Youth is a collaboration between (listed alphabetically): Chignecto-Central Regional School Board; Children's Aid Societies of Pictou & Colchester Counties; Department of Psychology at Dalhousie University; Early Intervention Services; Family and Children's Services of Cumberland; Mental Health Services of Cumberland, Colchester/East Hants & Pictou Counties; Nova Scotia Departments of Community Services, Justice, Public Health Services and Sport & Recreation; the Shubenacadie Band Council. This project was partially supported by grants to Dr. Waschbusch from the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation (#304E) and from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (839-2000-1061). We would like to thank the students, parents, teachers, principals, and administrators who helped make this project possible

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Waschbusch, D.A., King, S. & Gregus, A. Age of Onset of ADHD in a Sample of Elementary School Students. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 29, 9–16 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-006-9020-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-006-9020-2