Abstract

Solid-state NMR has emerged as an important tool for structural biology and chemistry, capable of solving atomic-resolution structures for proteins in membrane-bound and aggregated states. Proton detection methods have been recently realized under fast magic-angle spinning conditions, providing large sensitivity enhancements for efficient examination of uniformly labeled proteins. The first and often most challenging step of protein structure determination by NMR is the site-specific resonance assignment. Here we demonstrate resonance assignments based on high-sensitivity proton-detected three-dimensional experiments for samples of different physical states, including a fully-protonated small protein (GB1, 6 kDa), a deuterated microcrystalline protein (DsbA, 21 kDa), a membrane protein (DsbB, 20 kDa) prepared in a lipid environment, and the extended core of a fibrillar protein (α-synuclein, 14 kDa). In our implementation of these experiments, including CONH, CO(CA)NH, CANH, CA(CO)NH, CBCANH, and CBCA(CO)NH, dipolar-based polarization transfer methods have been chosen for optimal efficiency for relatively high protonation levels (full protonation or 100 % amide proton), fast magic-angle spinning conditions (40 kHz) and moderate proton decoupling power levels. Each H–N pair correlates exclusively to either intra- or inter-residue carbons, but not both, to maximize spectral resolution. Experiment time can be reduced by at least a factor of 10 by using proton detection in comparison to carbon detection. These high-sensitivity experiments are especially important for membrane proteins, which often have rather low expression yield. Proton-detection based experiments are expected to play an important role in accelerating protein structure elucidation by solid-state NMR with the improved sensitivity and resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

High-resolution three-dimensional structures are crucial to the understanding of the mechanisms of protein functions. In recent years, solid-state NMR has become a new structural biology tool that has enabled structure determination for protein samples in various physical states, including micro-crystalline (Castellani et al. 2002; Lange et al. 2005; Zhou et al. 2007b; Franks et al. 2008; Loquet et al. 2008; Manolikas et al. 2008; Bertini et al. 2010; Jehle et al. 2010; Huber et al. 2011; Linser et al. 2011a), fibrillar (Jaroniec et al. 2004; Ferguson et al. 2006; Iwata et al. 2006; Wasmer et al. 2008; Nielsen et al. 2009), and membrane-bound forms (Mani et al. 2006; Cady et al. 2010). So far, the largest proteins with a structure determined using solid-state NMR are around 20 kDa (Bertini et al. 2010; Jehle et al. 2010). Chemical shift assignments for significant portion of residues have recently been demonstrated for larger proteins such as the 25 kDa HET-s (Schuetz et al. 2010), the 28-kDa proteorhodopsin (Shi et al. 2009), and the 33-kDa Ure2 prion (Habenstein et al. 2011). To expand the applications to larger and more biologically complex systems demands improvement in both experimental sensitivity and resolution. For instance, G-protein coupled receptors, which are carriers of important cellular signal transduction events and prime drug targets, often have 30–70 kDa molecular weights (Filmore 2004; Blois and Bowie 2009). Furthermore, mammalian membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to express in milligram quantities when minimal growth media are used for isotope enrichment. Until very recently, most NMR studies of solid proteins have been performed with direct 13C detection, whose suboptimal sensitivity is well known. Recently, 3–5 fold of signal enhancement has been achieved by using indirect proton detection in comparison to direct 13C detection (Reif et al. 2001; Chevelkov et al. 2003; Paulson et al. 2003; Chevelkov et al. 2006). The key to successful proton detection in the solid-state is the ability to obtain sufficiently narrow proton linewidths (Ishii et al. 2001), which were realized by the introduction of fast magic-angle spinning (MAS) triple resonance probe technology (Zhou et al. 2007a, 2009; Zhou and Rienstra 2008b) in combination with proton isotope dilution methods (Reif et al. 2001; Chevelkov et al. 2003, 2006; Paulson et al. 2003).

The first and often most challenging step of protein structure determination by NMR is the site-specific resonance assignment. In solution NMR, proton-detected experiments HNCO/HN(CA)CO, HN(CO)CA/HNCA, and HN(CO)CACB/HNCACB have been in routine use for many years for chemical shift assignments (Ikura et al. 1990; Kay et al. 1990; Grzesiek and Bax 1992a, b, c; Wittekind and Mueller 1993). The first experiment of each pair establishes correlation between the amide proton and nitrogen of residue i with carbon resonances of residue i − 1; the second experiment of each pair connects the amide group of residue i with carbon resonances from both residues i − 1 and i. Each pair facilitates sequential backbone assignments, but the third pair is especially powerful because the 13Cβ chemical shifts are indicative of amino acid type and an excellent source of chemical shift dispersion, albeit with much lower sensitivity in some experimental implementations. More recently new types of solution NMR experiments have also been developed to observe exclusively intra-residue correlations: iHN(CA)CO, iHNCA, and iHNCACB (Nietlispach et al. 2002; Nietlispach 2004; Permi and Annila 2004; Tossavainen and Permi 2004). These experiments are invaluable for studies of large proteins because they reduce signal crowding by a factor of two. In the solid-state, Reif and coworkers have implemented HNCO, HNCA, HNCOCA and HNCACB J-coupling based pulse sequences, exploiting the long 1H T2 relaxation times (>50 ms) of perdeuterated proteins that were fractionally back-exchanged with 10 % H2O and 90 % D2O (Linser et al. 2008, 2010a, b). They have demonstrated applicability of these experiments to microcrystalline, fibrillar and membrane proteins (Linser et al. 2011b).

Recently, Pintacuda and coworkers developed (H)CO(CA)NH and (H)CA(CO)NH experiments and applied them to a 16 kDa deuterated protein (human superoxide dismutase) back-exchanged with 100 % H2O (Knight et al. 2011). In this case, J-coupling based 13C–13C polarization transfer was made highly efficient by the combination of ultra-high field (1 GHz 1H Larmor frequency) and ultrafast MAS (60 kHz) (Knight et al. 2011). By virtue of RFDR 1H–1H mixing, well-resolved long-range distance restraints were also obtained in order to determine a high-resolution protein structure with less than 4 mg of protein and 8 days of measurement time. This study represents a major achievement and has motivated us to investigate the range of applicability of these and related pulse sequences for several protein systems. This includes the application of previously developed pulse sequences (as noted in the following paragraph), as well as modifications that we have found beneficial for improving sensitivity and resolution for large proteins with a high degree of chemical shift degeneracy; e.g., predominantly helical membrane proteins and predominantly β-sheet fibrous proteins.

In cases where T2 relaxation times are 10 ms or less, as typical for fully protonated samples and 100 % back-exchanged deuterated samples spinning under 40 kHz, we have found that dipolar polarization transfers are more efficient. This is consistent with the findings of Akbey et al. in their isotopic dilution study (Akbey et al. 2010). For these type of samples, triple-resonance experiments such as CANH and CONH by Zhou and Rienstra (Zhou et al. 2007a; b) and DQ(CXCA)NH and DQ(CACO)NH by Ladizhansky (Ward et al. 2011) have previously been developed. Motivated by the dramatically reduced T2 relaxation times in non-crystalline samples of partially back-exchanged perdeuterated proteins, Linser has recently developed hCxhNH, hCαhNH, and hCOhNH experiments by using long-range cross polarization (Linser 2012). Linser’s pulse sequences have the benefit of low signal loss; however, 13C resonances from both residues i and i − 1 correlate to the ith amide group may result in more signal overlap for larger proteins.

Here, we report four new dipolar-based experiments CO(CA)NH, CA(CO)NH, CBCA(CO)NH and CBCANH to complement and extend upon the above-mentioned experiments. The new experiments exclusively correlate i residue to itself or to i − 1 residue, but not both, thus effectively doubling spectral resolution while also maximizing sensitivity in terms of efficient polarization transfer. In CBCANH and CBCA(CO)NH experiments, Cβ and Cα are distinguished by opposite sign in intensity; the presence of Cβ resonances greatly accelerates the signal assignment process. For helical threonines and serines, which tend to have very close Cβ and Cα chemical shifts, these two experiments can be optimized for Cβ sensitivity so as to prevent peak cancelation. Meanwhile, strong Cα resonances are readily available in the more sensitive CANH and CA(CO)NH. Using these experiments, we have assigned the backbone sites of fully protonated GB1 (6 kDa) (Gronenborn et al. 1991; Franks et al. 2005), deuterated DsbA (21 kDa) back-exchanged with H2O (Inaba and Ito 2008), the membrane protein DsbB (20 kDa) (Li et al. 2008; Tang et al. 2011a, c), and alpha-synuclein (AS) (14 kDa) fibrils (Heise et al. 2005; Kloepper et al. 2006, 2007). Moreover, proton–proton distance restraints as long as 10 Å can be observed using these pulse sequences with slight modification. Therefore, proton-detection based experiments are expected to play a critical role in expanding the practical molecular size limit.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

A nanocrystalline sample of uniformly 13C,15N-labeled protein GB1 was prepared according to protocols that we have previously presented (Franks et al. 2005). Of the total ~9 mg material packed into a 1.6 mm FastMAS Varian/Agilent (Santa Clara, CA and Loveland, CO) NMR rotor, slightly more than half by mass (~5 mg, ~0.9 mmol) was protein (Zhou et al. 2007a).

Escherichia coli cells transformed with DsbA plasmid (Sperling et al. 2010) was adapted in 90 % D2O based media, which also contained labeled 15NH4Cl, 2H, 13C-glucose, and 2H,13C,15N-BioExpress (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.). The protein expression was induced while the cells were grown in 99 % D2O based media. The same adaptation strategy was employed when expressing perdeuterated DsbB and AS. The resultant protein was concentrated to ~9 mg/ml, and the solution was incubated at 4 °C for 11 days to allow exchangeable sites to be replaced by protons. Oxidization was achieved by adding oxidized glutathione to 10 mM. The solution was further concentrated to ~50 mg/ml and crystallized as described (Sperling et al. 2010). White nanocrystalline DsbA particles were then packed with a small amount of mother liquor into a 1.6 mm NMR rotor. The integrated intensity of a 13C one-pulse experiment, acquired with 100 s recycle delay, was compared with that of GB1, leading to the conclusion that sample contained about 3.3 mg (0.16 mmol) DsbA.

DsbB was purified from isolated membranes using dodecylmaltoside (DDM) as previously described (Li et al. 2008). Endogenous lipids were retained from the bacteria during the purification process (Li et al. 2007, 2008). All steps following cell breakage were done in 1H2O to facilitate amide proton exchange; the process lasted 7 days at 4 °C. A 13C one-pulse experiment indicated that ~2 mg of DsbB (0.1 mmol) were in the rotor.

The 2H,13C,15N-labeled AS protein was purified according to a previously reported protocol (Kloepper et al. 2006). Fibrils were prepared with seeding as previously reported (Kloepper et al. 2006) in buffers of 100 % 1H2O and 25 % 1H2O: 75 % 2H2O for two different samples. After fibrillation, fibrils were ultracentrifuged, dried and re-hydrated to 36 % water by mass, as previously described (Comellas et al. 2011) with 100 % 1H2O and 25 % 1H2O, respectively for each sample. Each sample contained about 6 mg protein.

NMR experiments

Solid-state NMR experiments were performed on a 750-MHz Varian INOVA spectrometer, using a Varian FastMAS HXY probe as previously reported (Zhou and Rienstra 2008a). The GB1 sample was spun at 40 kHz and its temperature regulated at 10 °C (calibrated sample temperature). Details of variable-temperature setup and calibration have been reported earlier (Zhou and Rienstra 2008a). The MAS rate for the DsbA sample was 36 kHz with temperature regulated at −10 °C and for DsbB was 38 kHz with temperature regulated at −12 °C. The MAS for AS fibrils was 40 kHz. For data processing, linear prediction was applied to indirect dimensions, extending 13Cα/13Cβ evolution time to 9 ms (not applied to 13C′), and 15N to 20 ms. Sine-bell apodization (54º shifted) was applied to each dimension, followed by Lorentzian-to-Gaussian apodization (100–200 Hz for 1H, 25–50 Hz for both 15N and 13C). Further experimental details can be found in figure captions and Supporting Information.

Results and discussion

Pulse sequence design

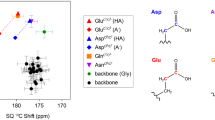

A set of six proton-detected triple-resonance three-dimensional solid-state NMR experiments have been refined for sequential backbone assignments of proteins, based on prior studies of high-sensitivity proton detection that has recently been accomplished in the solid state by fast MAS (Zhou et al. 2007a, 2009; Zhou and Rienstra 2008b) and proton dilution (Reif et al. 2001; Chevelkov et al. 2003, 2006; Paulson et al. 2003). The spin polarization pathways for the six experiments are represented in Fig. 1. The polarization remains within the same residue for the CANH (Fig. 1a), CO(CA)NH (Fig. 1c), and CBCANH (Fig. 1e) experiments. Inter-residue transfers take place in the CA(CO)NH (Fig. 1b), CONH (Fig. 1d), and CBCA(CO)NH (Fig. 1f) experiments, thus these experiments provide sequential connectivity. In the solution NMR counterpart experiments, spin polarization is transferred by J-coupling mediated mechanisms (Ikura et al. 1990; Kay et al. 1990; Grzesiek and Bax 1992a, b, c; Wittekind and Mueller 1993). In contrast, these solid-state implementations employ dipolar-interaction mediated mechanisms. Specifically, cross polarization (Hediger et al. 1994) is used for heteronuclear transfers, and dipolar recoupling enhancement through amplitude modulation (DREAM) (Verel et al. 1998; Detken et al. 2001; Ernst et al. 2004) is used for selective homonuclear transfer between C′–Cα or Cα–Cβ. With DREAM, transfer between C′–Cα is only feasible at relatively fast sample spinning rates (Table S1). A high performance multi-solvent suppression method MISSISSIPPI was used to suppress contaminating proton signals from water and lipids (Zhou and Rienstra 2008a). Pulse sequence design (Fig. S1), implementation, and practical aspects for these new experiments are discussed in detail in the Supporting Information. The pulse sequence codes for Agilent/Varian Inova spectrometers are available from the authors upon request. These new experiments have been applied to make sequential assignments for protein GB1 with full protonation, microcrystalline DsbA, membrane protein DsbB, and AS fibrils.

Spin polarization transfer pathways for the six 3D triple-resonance experiments. The pathways are represented for a CANH, b CA(CO)NH, c CO(CA)NH, d CONH, e CBCANH, and f CBCA(CO)NH. The initial 1H to 13C cross polarization step is omitted for clarity in the drawing. Bold font is used for a nucleus whose chemical shift is allowed to evolve. In e and f both Cβ and Cα evolve during the same time

Application to fully-protonated small proteins

We first utilized the β1 immunoglobulin binding domain of protein G (GB1, 56 residues), a protein that has been well characterized by both solution and solid-state NMR (Gronenborn et al. 1991; Franks et al. 2005). The six experiments were acquired in 10, 10, 16, 16, 16, and 32 h for CONH, CO(CA)NH, CANH, CA(CO)NH, CBCANH, and CBCA(CO)NH, respectively (Fig. 2). All Cα, C′, N, and HN signals were identified in the first four spectra, with the exception of N and HN signals for Met1. The chemical shift assignments, which were made using only the proton-detected data, are listed in Table S2 (also in BMRB with accession number 18397). For the two less efficient experiments CBCANH and CBCA(CO)NH, Cβ peaks are missing for several residues (L5, K13, E19, T25, Y33, T44, Y45, K50, T53), very likely due to unfavorable dynamics or exchange events. As shown in Fig. 2, the CBCA(CO)NH and CBCANH experiments were used to assist in the backbone assignments from G38 to W43. 13Cα and 13Cβ signals were distinguished by opposite signs since the 13Cβ signal passed through a double-quantum DREAM filter (Verel et al. 1998). Within each pair of spectra, the related peaks have the same 15N and 1HN frequencies from the ith residue, but the 13C frequencies in the inter- and intra-residue correlation experiments are from (i − 1)th and ith residues, respectively. The first pair of strip plots illustrated at 121.7 ppm 15N frequency and 8.3 ppm 1H frequency can be easily identified as a Gly–Val pair due to the characteristic Gly 13Cα and Val 13Cα, 13Cβ, and 13Cγ chemical shifts. 13Cγ signals of valine and other amino acids are also detected by first passing through a 13Cγ–13Cβ transfer, which takes place during the DREAM unit intended for 13Cβ–13Cα transfer due to similar DREAM conditions. These 13Cγ signals change sign twice, resulting in the same sign as that of 13Cα. The 15N and 1H frequencies for the next residue are identified by searching through the CBCA(CO)NH spectrum for V39 13C frequencies. This process is repeated to continue the backbone walk for the entire protein. Gly 13Cα tend to correlate to 15N and 1H of nearby residues, because Gly has no sidechain, as evident for both G38 and G41 in Fig. 2. Therefore special attention has to be paid when interpreting Gly peaks. The application to GB1 is a demonstration that these experiments can be efficiently acquired and analyzed for small proteins without proton dilution, thus avoiding the practical challenges and cost of deuteration. In the context of antimicrobial peptides (Hong 2007), it may be preferable to utilize samples prepared without deuteration by solid-phase peptide synthesis. The ability to perform full 1H assignments without deuteration, therefore, could provide substantial benefit and enable more efficient study of this class of peptides.

Sequential backbone walk from G38 to W43 for protein 13C,15N-GB1. Pairs of CBCA(CO)NH (left) and CBCANH (right) were acquired in 32 and 16 h, respectively. The evolution times were t1max(13C) = 7 ms and t2max(15N) = 19 ms. Each strip is 3 ppm wide. Positive and negative contours are shown in red and blue, respectively

Application to proton-diluted proteins

DsbA is a strong thiol oxidant involved in the catalysis of protein folding through the formation of disulfide bonds in the periplasm of E. coli (Inaba and Ito 2008). Its chemical shifts have been determined in solution state (Couprie et al. 1998) and in the solid state using 13C-detected 3D and 4D experiments (Sperling et al. 2010). Here proton-detected experiments were performed on this 21 kDa protein to demonstrate the capability of achieving residue-specific assignments for relatively large proteins of mixed secondary structure, by exploiting unique Cβ 13C chemical shift information.

Figure 3a is a 15N–1H 2D correlation spectrum acquired in 25 min on only ~3.3 mg (0.16 mmol) of DsbA that is triply labeled (2H,13C,15N) and back-exchanged with H2O. Approximately 25 peaks were resolved in this 2D spectrum, necessitating 3D methods to obtain a full assignment. The suite of six 3D experiments was applied to improve spectral resolution. Figure 3b–d shows three 2D planes from a CONH 3D spectrum (acquired in 12 h) and demonstrates the resolution provided by the indirect CO dimension; the majority of peaks are well resolved in the 3D spectra.

15N–1H 2D (a) and CONH 3D (b–d) spectra of the re-exchanged 2H,13C,15N-DsbA. This 15N–1H 2D spectrum was acquired in 25 min with t1max(15N) = 12.5 ms and processed with sine bell apodization (54° shifted) and followed by Lorentzian-to-Gaussian apodization (40–60 Hz for 1H and 10–20 Hz for 13C). CONH was acquired in 12 h with t1max(13C) = 14 ms, t2max(15N) = 20 ms

In Fig. 4 several complementary features of the CANH and CBCANH spectra can be examined with 2D planes taken at F2(15N) = 116.0 ppm and 114.9 ppm. In the CBCANH spectrum (Fig. 4b, d), 5 ms DREAM mixing time for CB-CA transfer was deliberately chosen so that Cβ intensities were stronger than those of Cα. The dependence of Cβ and Cα intensities on DREAM times can be evaluated with the acquisition of several 2D CBCA(N)H spectra by holding the 15N evolution time constant in the CBCANH pulse sequence. A DREAM of 3 ms yielded balanced Cα and Cβ intensities of opposite signs (data not shown). However, this is unfavorable for helical threonines and serines, which tend to have very close 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts. For example, S106 and S186 have nearly identical 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts (Fig. 4) and their intensity would have canceled with each other had the CBCANH spectrum been acquired with 3 ms DREAM. By optimizing for Cβ intensity, strong S106 and S186 Cβ peaks appeared in the CBCANH spectrum (Fig. 4b, d). The complementary 13Cα information is readily available in the CANH spectra, which is more sensitive and can be obtained in a fraction of the CBCANH experiment time, as shown in Fig. 4a, c. These arguments are equally applicable to the cases of CA(CO)NH and CBCA(CO)NH.

Complementary features of CANH (a) and (c) and CBCANH (b) and (d) 3D spectra for the re-exchanged 2H,13C,15N-DsbA. The 2D planes were taken with F2(15N) = 116.0 ppm (a, b) and 114.9 ppm (c, d). In b and d, negative peaks are shown in blue and positive in red. The CANH spectrum was acquired in 12 h with t1max(13C) = 7 ms, t2max(15N) = 11 ms. The CBCANH was acquired in 5 days with t1max(13C) = 4.7 ms, t2max(15N) = 11 ms

Figure 5 demonstrates the sequential backbone walk from E4 to K14 with data from four experiments, CA(CO)NH, CBCA(CO)NH, CANH, and CBCANH. The complementary experiments CA(CO)NH and CANH were overlaid with CBCA(CO)NH and CBCANH, respectively. The other two spectra (CONH and CO(CA)NH) can be found in Fig. S2. In addition, the Cβ and Cγ peaks of T10, T11, and L12 were detected with the same sign as the Cα peaks. For L12, even the Cδ peak was detected after passing multiple transfer steps during the Cβ–Cα DREAM. The presence of the side chain carbon resonances greatly accelerated the assignment process by facilitating the determination of amino acid types and providing an additional source of chemical shift dispersion (Zhou et al. 2006a). In the 2D plane with 115.2 ppm 15N frequency (Fig. 5), the K7 13C to Q8 15N and 1HN cross peaks in the CBCA(CO)NH spectrum were too weak to be observed. However, relatively strong cross peaks in the CA(CO)NH (Fig. 5) and CONH (Fig. S2) assisted in making the K7 to Q8 connection.

Sequential backbone walk from E4 to K14 for the re-exchanged 2H,13C,15N-DsbA. Pairs of CBCA(CO)NH and CBCANH (from left to right) 2D strip plots are shown with F2(15N) frequency indicated at the top of the figure. Positive contours are shown in red and negative in blue. Also CA(CO)NH and CANH (from left to right; both in black) are overlaid beneath CBCA(CO)NH and CBCANH, respectively. Each strip plot is 0.5 ppm wide and the 1H central frequency is labeled at the bottom. The CANH spectrum was acquired in 12 h with t1max(13C) = 7 ms, t2max(15N) = 11 ms. CA(CO)NH was acquired in 2 days with the same evolution times as CANH. The CBCANH was acquired in 5 days with t1max(13C) = 4.7 ms, t2max(15N) = 11 ms. CBCA(CO)NH was acquired in 10 days with the same evolution times as CBCANH

The chemical shift assignments for DsbA are listed in Table S3 (also in BMRB with accession number 18396). In total 137 pairs of 15N and 1HN have been assigned, out of the 181 maximum assignable pairs (189 residues excluding seven prolines and the N-terminal A1). Additionally, there are 137 C′, 152 Cα, and 117 Cβ chemical shifts assigned. Except for a small number of residues (S43, G53, V54, T73, Q74, L92, F93, E94, G95), assignments listed in Table S3 were performed without consulting pre-existing solution or 13C-based solid assignments. Total experimental time was 12 days for 3.3 mg protein. For 13C-detection based assignments, 29 days of experimental time was used on three 18-mg protein samples respectively labeled uniformly and with 1,3-13C and 2-13C glycerol patterns (Sperling et al. 2010).

The proton-detection based solid-state chemical shifts agree well with previous solution NMR assignments (Couprie et al. 1998), yielding coefficients of determination R2 = 0.978 for 1HN, 0.995 for 15N, 0.994 for C′, and 0.997 for Cα (Fig. S3). Chemical shifts of proteins have been shown to vary between solution and solid-state, because they are quite sensitive to many factors such as secondary structure, hydrogen bonding, crystal contact, proximate solvent molecule, and protonation state (Franks et al. 2005). The following residues demonstrated relatively large chemical shift alterations between the solid and solution states (Fig. S3): 1HN for G65 by over 1 ppm; 15N of G65 and V150 by over 1.5 ppm; C′ of M64 and G65 by over 1.0 ppm; Cα of E38, G65 by over 1.5 ppm. Interestingly, these sites fall within the regions that demonstrated significant chemical shift perturbations between oxidized and reduced DsbA: regions around the active site (residues 26–43), around His60, Gln97, and Pro151 (Couprie et al. 1998). In our previous study of non-deuterated nano-crystalline DsbA, large chemical shift variations for sites including E38, M64, G65, G66 were also observed between solid and solution states (Sperling et al. 2010).

The unassigned residues, not detected in these experiments, were mostly located in the rigid regions of the structure as indicated by small B factors of the crystal structure (Fig. 6). Reif, Oschkinat, and coworkers performed 15N–1H 2D experiments on perdeuterated SH3 back-exchanged with various concentration of H2O, and found a significant number of peaks in rigid regions that were not observed for samples exchanged with 80–100 % H2O (Akbey et al. 2010), where the dipolar interactions were large enough to broaden proton resonances from detection. In that study, a relatively low spinning rate (24 kHz) and magnetic field (400 MHz proton frequency) were employed. In the current study, a high spinning rate (40 kHz) and magnetic field (750 MHz) helped to effectively reduce proton linewidths (Zhou et al. 2007a). As a result, even for non-deuterated GB1, nearly all expected peaks were observed. Even though proton linewidths were narrower for the perdeuterated and back-exchanged DsbA sample, the DsbA sample contained only ~0.16 µmol of protein, much less than ~0.9 mmol for the GB1 sample. As a result, the broad peaks of some DsbA residues were too weak to be detected in the spectra acquired in limited amount of time. It may be possible to increase both spectral resolution and sensitivity by several folds for a perdeuterated DsbA sample back-exchanged with roughly 40–50 % H2O (Akbey et al. 2010). Therefore, these residues may appear for such a sample and with longer data acquisition time.

Correspondence of rigid regions and disappearance of 1H NMR resonance peaks. a DsbA crystal structure (PDB 1 A2J) colored according to B factor value with the color scale displayed. Regions colored in blue are rigid. b Residues that were not assigned (in blue) using proton detected experiments for the perdeuterated DsbA back-exchanged with 100 % H2O nano-crystalline sample

Application to membrane proteins

To explore the applicability of these experiments to non-crystalline solid protein samples, we acquired the CANH and CONH 1H-detected 3D spectra of the 20 kDa membrane protein DsbB C41S, with additional mutation of two nonessential cysteines C8A and C49 V. DsbB, which is an integral membrane protein in E. coli consisting of four transmembrane helices, is responsible for reoxidizing DsbA and transferring the electrons to ubiquinone to continue the disulfide bond generating cycle (Inaba and Ito 2008). Approximately 2 mg (0.1 μmol) of 2H,13C,15N-labeled DsbB, back-exchanged with H2O, was packed into a 1.6 mm rotor with lipids and water for this study and 15N–1H 2D (Fig. 7a) and a CANH 3D (Fig. 7b–d) were acquired. These data demonstrate that 1H linewidths comparable to nanocrystalline proteins can be obtained in NH 2D and CANH 3D spectra on membrane protein samples. Additionally, a CONH 3D spectrum was acquired for establishing inter-residue connectivity (data not shown). The sensitivity enhancement due to 1H detection enabled the acquisition of each 3D spectrum in only 2 days of instrument time. The resolution in the three-dimensional spectra is sufficient to resolve the majority of the observed signals in this system, despite the fact that helical residues have low chemical shift dispersion.

These two preliminary 3D data sets were not sufficient for de novo assignments, therefore we assigned the resolved peaks with assistance from two sets of previous chemical shift assignments: assignments of the transmembrane helices of the same C41S mutant by 13C-detection solid-state NMR (Li et al. 2008) and solution NMR assignments of another mutant (with mutations C44S, C49A, C104S) that imitates an intermediate state of disulfide bond formation (Zhou et al. 2008). All sites assigned based on 13C-detection experiments were located in transmembrane domains (Li et al. 2008), as highlighted in a structure model (Fig. S4b). The solution NMR data (Zhou et al. 2008) helped to make other assignments. The solid-state 1H assignments are listed in Table S4 (also in BMRB with accession number 18395) and highlighted in a topology model of DsbB in Fig. S4a. In comparison, the previous 13C-detection based study enabled assignment of about 70 % of the 80 residues in the four transmembrane helices (Fig. S4b), but only two out of the remaining 96 residues were assigned for the cytoplasmic and periplasmic loops (Li et al. 2008). Signals from the loop regions were too weak to detect, which was attributed to structural inhomogeneity in these regions (Li et al. 2008). On the other hand, the proton-detected data enabled assignments of many sites in the flexible loop regions as well as many transmembrane sites close to the surface (Fig. S4a), complementing the previous 13C-detected data. Combining the assignments from 13C- and 1H-detected data allowed 74 out of 80 transmembrane residues to be assigned (Fig. S4a). Increased dynamics at higher experimental temperature in this study (−12 vs. −40 °C in previous 13C-detected experiments) very likely contributed to the reduced structural inhomogeneity in the loop regions. Still some residues in the loop regions remained unassigned. It is possible they correspond to a number of unassigned peaks in the two 3D spectra. With additional 3D experiments, we expect to assign the majority of the loop residues. Conversely, several sites on the first three transmembrane helices away from the surface and most sites in the fourth transmembrane helix were not assigned (Fig. S4a). Structural rigidity, similar to what was described for DsbA, may render them undetectable with the temperature and amount of data acquisition time used in this study. Moreover, insufficient back-exchange with H2O may also be partially responsible for the disappearance of some of these lipid-embedded sites. Additional improvements in 1H back-exchange protocols are expected to result in additional signals from the transmembrane helices and should enable complete de novo assignments. For example, Bushweller and coworkers accomplished complete 2D/1H exchange by using SDS to partially unfold DsbB followed by removal of SDS (Otzen 2003; Zhou et al. 2008).

The solid-state chemical shifts are compared with the solution NMR assignments (Zhou et al. 2008), yielding coefficient of determination R2 = 0.718 for 1HN, 0.983 for 15N, 0.959 for C′, and 0.981 for Cα (Fig. 8). The correlation between solid and solution chemical shifts, especially for protons, is worse than in the DsbA. The outliers marked in Fig. 8 can be divided into four groups. First, residues near the membrane surface (A14, A73, V75, T92, Y97, W145, S163; see Fig. S4 for a topology model positioning amino acids with respect to the lipid bilayer) are impacted by different headgroups in the two studies. In the current study, endogenous lipids were retained from the bacteria during the purification process (Li et al. 2007; 2008), while in the solution NMR, dodecyl phosphocholine micelles were used (Zhou et al. 2008). This is consistent with our previous study on protonated DsbB, where several sites that are close to the membrane surface also demonstrate large chemical shift deviation from solution NMR (Tang et al. 2011b). Second, residues in the middle of transmembrane helices (L25, L27 and Y153) likely experience different hydrogen-bonding environments in lipid bilayers versus detergent micelles. Third, residues close to position C130 (A126, S127, G128, D129) can be explained by proximity to the C41–C130 disulfide bond in the solution sample. These two mutants represent two different disulfide-bond forming reaction states (Zhou et al. 2008). As a result, their structures are expected to be different, for instance, an inter-loop disulfide bond was formed between C41 and C130 in the mutant used in solution NMR. Fourth, the remaining outliers (A102, T103, and W113) are also in the loop. If the corresponding loop segments are close to the membrane surface, then head groups can also impact their chemical shift. It is also possible that the C41–C130 disulfide bond may indirectly impact these sites by causing structural rearrangement in the loop.

Comparison of solid-state chemical shifts of deuterated DsbB in lipids in this study and solution chemical shifts of DsbB in detergent micelle from a previous study (Zhou et al. 2008). The data were fit by y = x + b, with parameter b accounting for a small chemical shift reference difference in the two studies and isotope shift effects arose from use of a deuterated sample in the current study (Hansen 2000). The b value along with coefficient of determination R 2 are written in each sub-figure. Residues are labeled for relatively large chemical shift differences, |y i − (x i + b)| > Δ, where Δ = 0.8 for amide protons in (a), 1.5 for 15N in (b), 1.0 for 13C′ in (c), and 1.5 for 13Cα in (d)

Application to fibrillar proteins

The assignment of protein fibrils presents a special challenge due to the repetitive amino acid sequences and homogeneous secondary structure. AS fibrils are the major proteinaceous component of Lewy bodies, the pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease (Spillantini et al. 1997). AS represents an example of a relatively large fibril core that we have previously investigated using 13C-detected methodology (Comellas et al. 2011). 2H,13C,15N-labeled AS fibrils were prepared from monomer back-exchanged with H2O, such that the amide protons were present prior to fibrillation; the NMR sample contained about 400 nmol of protein. Although the 15N–1H 2D spectrum resolved only ~ 12 sites uniquely (Fig. 9a), chemical shift assignments could be performed with the six 3D experiments (Fig. S5). In the assignment process, we found it critical to have the Cβ chemical shift dispersion in CBCANH and CBCA(CO)NH experiments. These experiments enabled the backbone walk for the core of AS fibrils residues 42–55 (except for H50 and G51) and residues 63–97, providing the amide proton assignments and confirming 13C and 15N assignments obtained from 13C-detected experiments (Comellas et al. 2011). In 41 out of 48 cases the CA and C′ resonance could be seen in both the CANH/CAcoNH and CONH/COcaNH pairs. In regions with the most signal, for example 85–95 (Fig. S5), the CB resonance was also seen in the CBCANH/CBCAcoNH pair. In other regions, the CB resonance was only observed in the CBCANH 3D, which still enabled residue type assignments. The assignments are listed in Table S5 (also in BMRB with accession number 18243).

For many regions of the protein, the 100 % 1H2O back-exchanged 2H,13C,15N-labeled fibrils provided sufficient resolution to implement a straightforward backbone assignment procedure. However, in some regions the ~0.2 ppm 1H linewidths resulted in overlap even in the 3D spectra. It is now well established that isotopic dilution of the 1H bath can further improve 1H linewidths. We demonstrated this effect in small organic molecules (Zhou et al. 2006b) and a systematic study was subsequently carried out on the protein SH3 (Akbey et al. 2010). In this case, we exchanged the amide sites in the AS monomer solution to 25 % 1H2O and 75 % 2H2O, and likewise incubated the fibrils with the same ratio of 1H to 2H in the buffer. This decreased the magnitude and number of 1H–1H couplings and in the fibril sample resulted in 1H linewidths of 0.05–0.1 ppm (15N–1H 2D shown in Fig. 9b). Although this sample exhibited half the absolute signal intensity as the fibrils back exchanged with 100 % 1H2O, 3D experiments could be carried out in similar measurement times, due to the benefit of the narrower 1H linewidths. Fig. S6 demonstrates 13C planes from the CONH spectrum for the sample back exchanged with 100 % 1H2O and the sample back exchanged with 25 % 1H2O. The line narrowing from dilution enables, for example, residues G93 and G47 (Fig. S6b) to be distinguished. In addition, peaks arising from residues E46 and V82 (Fig. S6a) are relatively broad in the spectrum acquired on the 100 % 1H2O sample, and show large relative improvement in resolution. For example, E46 is narrowed from 158 to 118 Hz in the 1H dimension. The improved resolution of the spectra acquired with the 25 % back-exchanged sample reduces ambiguity in the 1H chemical shift and increases confidence in assignments. This in turn significantly simplified the backbone walk procedures by reducing the number of possible spin systems for each site. In 14 cases, the 25 % sample enabled signals that were degenerate in the 100 % sample to be resolved. On the other hand, T54, which is very weak (signal-to-noise ratio of 13, compared to an average signal-to-noise of 21) in the spectrum taken on the 100 % 1H2O sample (Fig. S6c) does not appear in the spectrum acquired on the 25 % 1H2O sample. Additionally, the CBCANH and CBCA(CO)NH experiments are not sensitive enough to be practical on the 25 % 1H2O sample. Thus both samples were needed to achieve all the assignments made, with the 25 % 1H2O sample providing resolution in congested regions, and the 100 % 1H2O sample the vital CB resonance. In total, 12 days of measurement time was used on 6 mg of protein. For the 13C-detected experiments (Comellas et al. 2011) about 18 days of measurement time was used on 12 mg of protein with uniform-13C,15N labeling. In addition to the measurement time, the time required for proper parameter optimization was substantially decreased by at least two times with the 1H detection experiments versus the 13C detection versions.

Proton–proton distance constraints

We have shown earlier that proton distance restraints obtained from CON(H)H and HN(H)H experiments could be used to determine a high resolution structure for GB1 (Zhou et al. 2007b). Adding RFDR (Bennett et al. 1992) on the 1H channel right before data acquisition converts the two most sensitive experiments CONH and CANH to CON(H)H and CAN(H)H, respectively; RFDR actively recouples dipolar interactions to detect 1H–1H distances. These two experiments provide complementary 13C resolution and have been performed on the 2H,13C,15N-DsbA sample. The CON(H)H spectra are shown in Fig. 10 with increasing RFDR mixing times. With 2 ms mixing (Fig. 10a), cross peaks between the amide protons of L12 and sequential neighbors T10, T11, E13, and K14 are observed; T10 is 6.7 Å away from L12 according to a solution NMR structure (Fig. 10e, PDB code 1A23). With 4 ms mixing (Fig. 10b), these cross peaks become significantly stronger and the L12–Q160 amide proton correlation is observed. With 6 ms mixing (Fig. 10c), a correlation between L12 and Y159 starts to emerge. Finally, with 8 ms mixing (Fig. 10d), cross peaks with K158HN, Y9HN, and Q160Hε1 are observed. The Y9 amide proton is nearly 10 Å away from L12. In the CONH experiments, Cγ–Nδ–Hδ and Cδ–Nε–Hε correlations of asparagines and glutamines, respectively, also survive all polarization transfer steps. The Q160Hε1 resonance was identified by its correlation to Q160 amide 15N and 1HN in the CON(H)H acquired with 8 ms mixing.

CON(H)H 3D of DsbA for distance restraints. The 2D planes are captured at F2(15N) = 129.0 ppm. The experiments were performed with increasing RFDR mixing time of a 2, b 4, c 6, and d 8 ms. Longer experiment times were used for longer mixing time: a 45, b 72, c 81, and d 90 h. t1max(13C) was acquired to 7 ms without linear prediction; t2max(15N) was acquired to 11 ms and linear predicted to 15 ms. e A region of the protein structure (PDB code 1A23) showing proton distances observed in the correlation spectra

In the majority of cases for proteins 20 kDa or larger, many degenerate or nearly degenerate 1H chemical shifts are expected. Therefore a significant degree of ambiguity will be present when assigning the distances to proton pairs. We have recently shown that including this ambiguity in restraint lists does not necessarily prevent the convergence of structure calculations if enough unambiguous data is available (Nieuwkoop and Rienstra 2010). In addition, structure calculations and distance assignments can be performed iteratively, as has been demonstrated in many cases (Fossi et al. 2005). It is also possible to greatly reduce distance assignment ambiguity by designing 4D experiments such as CON(HH)NH and CAN(HH)NH. The latter correlates 15Cαi and 15Ni to 15Nj and 1HNj for any two amide protons close in space. The condition i = j gives the auto-correlation peak, thus residue i is still encoded with all three frequencies. Meanwhile, residue j is encoded with both 15N and 1HN frequencies.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated chemical shift assignments using a set of six dipolar-based 3D triple resonance experiments designed for high sensitivity proton detection for samples of relatively high protonation levels in a variety of sample conditions. Four experiments CANH, CONH, CA(CO)NH, and CO(CA)NH, which already facilitate de novo sequential assignments, can be acquired in 1 or 2 days for ~2–3 mg of proteins. The other two experiments CBCANH and CBCA(CO)NH, which take more measurement time to complete, may nevertheless speed up assignment process by virtue of simplified analysis. These experiments effectively double the resolution power since they select either intra- or inter-residue correlations but not both. With these experiments, we were able to make chemical shift assignments for fully-protonated small proteins without proton dilution and for relatively large proteins prepared with proton spin dilution. We also demonstrated that these experiments performed equally well with sparse proton samples prepared by back-exchanging perdeuterated samples with a mixture of H2O and D2O. We expect these experiments also work well at higher MAS rates to achieve even better resolution. Lewandowski et al. have recently demonstrated on microcrystalline perdeuterated α-spectrin SH3 that at 60 kHz MAS rate and 1 GHz proton Larmor frequency the 1H resolution is limited by inhomogeneous linewidths (Lewandowski et al. 2011). Resolution may be further improved by developing 4D experiments to reduce ambiguity in distance assignments. Two prominent candidates are COCANH and CACONH since they have the same polarization transfer efficiency as their 3D counter parts CO(CA)NH and CA(CO)NH. With slight modification, these experiments were used to detect proton distances. We have observed proton–proton distances as long as 10 Å, which are important to refine the tertiary protein structure. In short, these fast MAS based triple resonance can impact two important steps in protein structure determination: the chemical shift assignment and distance constraints acquisition. We expect these experiments will extend capabilities for determining structures of large proteins in the solid state.

References

Akbey U, Lange S, Franks TW, Linser R, Rehbein K, Diehl A, van Rossum B-J, Reif B, Oschkinat H (2010) Optimum levels of exchangeable protons in perdeuterated proteins for proton detection in MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR 46:67–73

Bennett AE, OK JH, Griffin RG, Vega S (1992) Chemical shift correlation spectroscopy in rotating solids: radio frequency-driven dipolar recoupling and longitudinal exchange. J Chem Phys 96:8624–8627

Bertini I, Bhaumik A, De Paepe G, Griffin RG, Lelli M, Lewandowski JR, Luchinat C (2010) High-resolution solid-state NMR structure of a 17.6 kDa protein. J Am Chem Soc 132:1032–1040

Blois TM, Bowie JU (2009) G-protein-coupled receptor structures were not built in a day. Prot Sci 18:1335–1342

Cady SD, Schmidt-Rohr K, Wang J, Soto CS, DeGrado WF, Hong M (2010) Structure of the amantadine binding site of influenza M2 proton channels in lipid bilayers. Nature 463:689–692

Castellani F, Rossum BV, Diehl A, Schubert M, Rehbein K, Oschkinat H (2002) Structure of a protein determined by solid-state magic-angle-spinning NMR spectroscopy. Nature 420:98–102

Chevelkov V, van Rossum BJ, Castellani F, Rehbein K, Diehl A, Hohwy M, Steuernagel S, Engelke F, Oschkinat H, Reif B (2003) 1H detection in MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopy of biomacromolecules employing pulsed field gradients for residual solvent suppression. J Am Chem Soc 125:7788–7789

Chevelkov V, Rehbein K, Diehl A, Reif B (2006) Ultra-high resolution in proton solid-state NMR spectroscopy at high levels of deuteration. Angew Chem Int Ed 45:3878–3881

Comellas G, Lemkau LR, Nieuwkoop AJ, Kloepper KD, Ladror DT, Ebisu R, Woods WS, Lipton AS, George JM, Rienstra CM (2011) Structured regions of α-synuclein fibrils include the early-onset parkinson’s disease mutation sites. J Mol Biol 411:881–895

Couprie J, Remerowski ML, Bailleul A, Courcon M, Gilles N, Quemeneur E, Jamin N (1998) Differences between the electronic environments of reduced and oxidized Escherichia coli DsbA inferred from heteronuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Protein Sci 7:2065–2080

Detken A, Hardy EH, Ernst M, Kainosho M, Kawakami T, Aimoto S, Meier BH (2001) Methods for sequential resonance assignment in solid, uniformly 13C, 15 N labelled peptides: quantification and application to antamanide. J Biomol NMR 20:203–221

Ernst M, Meier MA, Tuherm T, Samoson A, Meier BH (2004) Low-power high-resolution solid-state NMR of peptides and proteins. J Am Chem Soc 126:4764–4765

Ferguson N, Becker J, Tidow H, Tremmel S, Sharpe TD, Krause G, Flinders J, Petrovich M, Berriman J, Oschkinat H, Fersht AR (2006) General structural motifs of amyloid protofilaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:16248–16253

Filmore D (2004) It’s a GPCR world: cell-based screening assays and structural studies are fueling G-protein coupled receptors as one of the most popular classes of investigational drug targets. Mod Drug Discov 7:24–28

Fossi M, Castellani F, Nilges M, Oschkinat H, van Rossum B-J (2005) SOLARIA: a protocol for automated cross-peak assignment and structure calculation for solid-state magic-angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed 44:6151–6154

Franks WT, Zhou DH, Wylie BJ, Money BG, Graesser DT, Frericks HL, Sahota G, Rienstra CM (2005) Magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy of the β1 immunoglobin binding domain of protein G (GB1): 15N and 13C chemical shift assignments and conformational analysis. J Am Chem Soc 127:12291–12305

Franks WT, Wylie BJ, Frericks Schmidt HL, Nieuwkoop AJ, Mayrhofer RM, Shah GJ, Graesser DT, Rienstra CM (2008) Dipole tensor-based refinement for atomic-resolution structure determination of a nanocrystalline protein by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:4621–4626

Gronenborn AM, Filpula DR, Essig NZ, Achari A, Whitlow M, Wingfield PT, Clore GM (1991) A novel, highly stable fold of the immunoglobulin binding domain of streptococcal protein G. Science 253:657–661

Grzesiek S, Bax A (1992a) An efficient experiment for sequential backbone assignment of medium-sized isotopically enriched proteins. J Magn Reson 99:201–207

Grzesiek S, Bax A (1992b) Correlating backbone amide and side chain resonances in larger proteins by multiple relayed triple resonance NMR. J Am Chem Soc 114:6291–6293

Grzesiek S, Bax A (1992c) Improved 3D triple-resonance NMR techniques applied to a 31 kDa protein. J Magn Reson 96:432–440

Habenstein B, Wasmer C, Bousset L, Sourigues Y, Schütz A, Loquet A, Meier B, Melki R, Böckmann A (2011) Extensive de novo solid-state NMR assignments of the 33 kDa C-terminal domain of the Ure2 prion. J Biomol NMR 51:235–243

Hansen PE (2000) Isotope effects on chemical shifts of proteins and peptides. Magn Reson Chem 38:1–10

Hediger S, Meier BH, Kurur ND, Bodenhausen G, Ernst RR (1994) NMR cross polarization by adiabatic passage through the Hartmann–Hahn condition (APHH). Chem Phys Lett 223:283–288

Heise H, Hoyer W, Becker S, Andronesi OC, Riedel D, Baldus M (2005) Molecular-level secondary structure, polymorphism, and dynamics of full-length alpha-synuclein fibrils studied by solid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:15871–15876

Hong M (2007) Structure, topology, and dynamics of membrane peptides and proteins from solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B 111:10340–10351

Huber M, Hiller S, Schanda P, Ernst M, Böckmann A, Verel R, Meier BH (2011) A proton-detected 4D solid-state NMR experiment for protein structure determination. ChemPhysChem 12:915–918

Ikura M, Kay LE, Bax A (1990) A novel approach for sequential assignment of 1H, 13C, and 15 N spectra of larger proteins: heteronuclear triple-resonance three-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. Application to calmodulin. Biochemistry 29:4659–4667

Inaba K, Ito K (2008) Structure and mechanisms of the DsbB-DsbA disulfide bond generation machine. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783:520–529

Ishii Y, Yesinowski JP, Tycko R (2001) Sensitivity enhancement in solid-state 13C NMR of synthetic polymers and biopolymers by 1H NMR detection with high-speed magic angle spinning. J Am Chem Soc 123:2921–2922

Iwata K, Fujiwara T, Matsuki Y, Akutsu H, Takahashi S, Naiki H, Goto Y (2006) 3D structure of amyloid protofilaments of beta2-microglobulin fragment probed by solid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:18119–18124

Jaroniec CP, MacPhee CE, Bajaj VS, McMahon MT, Dobson CM, Griffin RG (2004) High-resolution molecular structure of a peptide in an amyloid fibril determined by magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:711–716

Jehle S, Rajagopal P, Bardiaux B, Markovic S, Kuhne R, Stout JR, Higman VA, Klevit RE, van Rossum B-J, Oschkinat H (2010) Solid-state NMR and SAXS studies provide a structural basis for the activation of aB-crystallin oligomers. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17:1037–1042

Kay LE, Ikura M, Tschudin R, Bax A (1990) Three-dimensional triple-resonance NMR spectroscopy of isotopically enriched proteins. J Magn Reson 89:496–514

Kloepper KD, Woods WS, Winter KA, George JM, Rienstra CM (2006) Preparation of a-synuclein fibrils for solid-state NMR: expression, purification, and incubation of wild-type and mutant forms. Protein Express Purif 48:112–117

Kloepper K, Zhou D, Li Y, Winter K, George J, Rienstra C (2007) Temperature-dependent sensitivity enhancement of solid-state NMR spectra of α-synuclein fibrils. J Biomol NMR 39:197–211

Knight MJ, Webber AL, Pell AJ, Guerry P, Barbet-Massin E, Bertini I, Felli IC, Gonnelli L, Pierattelli R, Emsley L, Lesage A, Herrmann T, Pintacuda G (2011) Fast resonance assignment and fold determination of human superoxide dismutase by high-resolution proton-detected solid-state MAS NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed 50:11697–11701

Lange A, Becker S, Seidel K, Pongs O, Baldus M (2005) A concept for rapid protein-structure determination by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed 44:2089–2092

Lewandowski JzR, Dumez J-N, Akbey Um, Lange S, Emsley L, Oschkinat H (2011) Enhanced resolution and coherence lifetimes in the solid-state NMR spectroscopy of perdeuterated proteins under ultrafast magic-angle spinning. J Phys Chem Lett 2:2205–2211

Li Y, Berthold DA, Frericks HL, Gennis RB, Rienstra CM (2007) Partial 13C and 15 N chemical-shift assignments of the disulfide-bond-forming enzyme DsbB by 3D magic-angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. ChemBioChem 8:434–442

Li Y, Berthold DA, Gennis RB, Rienstra CM (2008) Chemical shift assignment of the transmembrane helices of DsbB, a 20-kDa integral membrane enzyme, by 3D magic-angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. Prot Sci 17:199–204

Linser R (2012) Backbone assignment of perdeuterated proteins using long-range H/C-dipolar transfers. J. Biolmol. NMR 52:151–158

Linser R, Fink U, Reif B (2008) Proton-detected scalar coupling based assignment strategies in MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopy applied to perdeuterated proteins. J Magn Reson 193:89–93

Linser R, Fink U, Reif B (2010a) Assignment of dynamic regions in biological solids enabled by spin-state selective NMR experiments. J Am Chem Soc 132:8891–8893

Linser R, Fink U, Reif B (2010b) Narrow carbonyl resonances in proton-diluted proteins facilitate NMR assignments in the solid-state. J Biomol NMR 47:1–6

Linser R, Bardiaux B, Higman V, Fink U, Reif B (2011a) Structure calculation from unambiguous long-range amide and methyl 1H–1H distance restraints for a microcrystalline protein with MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 133:5905–5912

Linser R, Dasari M, Hiller M, Higman V, Fink U, LopezdelAmo J-M, Markovic S, Handel L, Kessler B, Schmieder P, Oesterhelt D, Oschkinat H, Reif B (2011b) Proton-detected solid-state NMR spectroscopy of fibrillar and membrane proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed 50:4508–4512

Loquet A, Bardiaux B, Gardiennet C, Blanchet C, Baldus M, Nilges M, Malliavin T, Bockmann A (2008) 3D Structure determination of the Crh protein from highly ambiguous solid-state NMR restraints. J Am Chem Soc 130:3579–3589

Mani R, Tang M, Wu X, Buffy JJ, Waring AJ, Sherman MA, Hong M (2006) Membrane-bound dimer structure of a beta-hairpin antimicrobial peptide from rotational-echo double-resonance solid-state NMR. Biochemistry 45:8341–8349

Manolikas T, Herrmann T, Meier BH (2008) Protein structure determination from 13C spin-diffusion solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 130:3959–3966

Nielsen JT, Bjerring M, Jeppesen MD, Pedersen RO, Pedersen JM, Hein KL, Vosegaard T, Skrydstrup T, Otzen DE, Nielsen NC (2009) Unique identification of supramolecular structures in amyloid fibrils by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed 48:2118–2121

Nietlispach D (2004) A selective intra-HN(CA)CO experiment for the backbone assignment of deuterated proteins. J Biomol NMR 28:131–136

Nietlispach D, Ito Y, Laue ED (2002) A novel approach for the sequential backbone assignment of larger proteins: selective intra-HNCA and DQ-HNCA. J Am Chem Soc 124:11199–11207

Nieuwkoop AJ, Rienstra CM (2010) Supramolecular protein structure determination by site-specific long-range intermolecular solid state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 132:7570–7571

Otzen DE (2003) Folding of DsbB in mixed micelles: a kinetic analysis of the stability of a bacterial membrane protein. J Mol Biol 330:641–649

Paulson EK, Morcombe CR, Gaponenko V, Dancheck B, Byrd RA, Zilm KW (2003) Sensitive high resolution inverse detection NMR spectroscopy of proteins in the solid state. J Am Chem Soc 125:15831–15836

Permi P, Annila A (2004) Coherence transfer in proteins. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc 44:97–137

Reif B, Jaroniec CP, Rienstra CM, Hohwy M, Griffin RG (2001) H-1-H-1 MAS correlation spectroscopy and distance measurements in a deuterated peptide. J Magn Reson 151:320–327

Schuetz A, Wasmer C, Habenstein B, Verel R, Greenwald J, Riek R, Böckmann A, Meier BH (2010) Protocols for the sequential solid-state NMR spectroscopic assignment of a uniformly labeled 25 kDa protein: HET-s(1–227). ChemBioChem 11:1543–1551

Shi L, Lake EMR, Ahmed MAM, Brown LS, Ladizhansky V (2009) Solid-state NMR study of proteorhodopsin in the lipid environment: secondary structure and dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta 1788:2563–2574

Sperling LJ, Berthold DA, Sasser TL, Jeisy-Scott V, Rienstra CM (2010) Assignment strategies for large proteins by magic-angle spinning NMR: the 21-kDa disulfide bond forming enzyme DsbA. J Mol Biol 399:268–282

Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M (1997) alpha-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388:839–840

Tang M, Berthold DA, Rienstra CM (2011a) Solid-state NMR of a large membrane protein by paramagnetic relaxation enhancement. J Phys Chem Lett 2:1836–1841

Tang M, Sperling L, Berthold D, Schwieters C, Nesbitt A, Nieuwkoop A, Gennis R, Rienstra C (2011b) High-resolution membrane protein structure by joint calculations with solid-state NMR and X-ray experimental data. J Biomol NMR 51:227–233

Tang M, Sperling LJ, Berthold DA, Nesbitt AE, Gennis RB, Rienstra CM (2011c) Solid-state NMR study of the charge-transfer complex between ubiquinone-8 and disulfide bond generating membrane protein DsbB. J Am Chem Soc 133:4359–4366

Tossavainen H, Permi P (2004) Optimized pathway selection in intraresidual triple-resonance experiments. J Magn Reson 170:244–251

Verel R, Baldus M, Ernst M, Meier BH (1998) A homonuclear spin-pair filter for solid-state NMR based on adiabatic-passage techniques. Chem Phys Lett 287:421–428

Ward ME, Shi L, Lake E, Krishnamurthy S, Hutchins H, Brown LS, Ladizhansky V (2011) Proton-detected solid-state NMR reveals intramembrane polar networks in a seven-helical transmembrane protein proteorhodopsin. J Am Chem Soc 133:17434–17443

Wasmer C, Lange A, Van Melckebeke H, Siemer AB, Riek R, Meier BH (2008) Amyloid fibrils of the HET-s(218-289) prion form a beta solenoid with a triangular hydrophobic core. Science 319:1523–1526

Wittekind M, Mueller L (1993) HNCACB, a high-sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amide-proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha- and beta-carbon resonances in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. B 101:201–205

Zhou DH, Rienstra CM (2008a) High-performance solvent suppression for proton-detected solid-state NMR. J Magn Reson 192:167–172

Zhou DH, Rienstra CM (2008b) Rapid analysis of organic compounds by proton-detected heteronuclear correlation NMR spectroscopy at 40 kHz magic-angle spinning. Angew Chem Int Ed 47:7328–7331

Zhou D, Kloepper K, Winter K, Rienstra C (2006a) Band-selective 13C homonuclear 3D spectroscopy for solid proteins at high field with rotor-synchronized soft pulses. J Biomol NMR 34:245–257

Zhou DH, Graesser DT, Franks WT, Rienstra CM (2006b) Sensitivity and resolution in proton solid-state NMR at intermediate deuteration levels: quantitative linewidth characterization and applications to correlation spectroscopy. J Magn Reson 178:297–307

Zhou DH, Shah G, Cormos M, Mullen C, Sandoz D, Rienstra CM (2007a) Proton-detected solid-state NMR spectroscopy of fully protonated proteins at 40 kHz magic-angle spinning. J Am Chem Soc 129:11791–11801

Zhou DH, Shea JJ, Nieuwkoop AJ, Franks WT, Wylie BJ, Mullen C, Sandoz D, Rienstra CM (2007b) Solid-state protein-structure determination with proton-detected triple-resonance 3D magic-angle-spinning NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed 46:8380–8383

Zhou Y, Cierpicki T, Jimenez RHF, Lukasik SM, Ellena JF, Cafiso DS, Kadokura H, Beckwith J, Bushweller JH (2008) NMR solution structure of the integral membrane enzyme DsbB: functional insights into DsbB-catalyzed disulfide bond formation. Mol Cell 31:896–908

Zhou DH, Shah G, Mullen C, Sandoz D, Rienstra CM (2009) Proton-detected solid-state NMR of natural abundance peptide and protein pharmaceuticals. Angew Chem Int Ed 48:1253–1256

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health for financial support (R01 GM-75937 and R01 GM-73770 to C.M.R and R15 GM-097713 to D.H.Z.). We also thank the NMR Facility at the School of Chemical Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, D.H., Nieuwkoop, A.J., Berthold, D.A. et al. Solid-state NMR analysis of membrane proteins and protein aggregates by proton detected spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR 54, 291–305 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10858-012-9672-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10858-012-9672-z