Abstract

Nitrogen is a key dopant in Czochralski silicon widely used to control properties of Si wafers for applications in the microelectronics industry. Most of these properties are affected by defects and their processes. Here we employ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to investigate the existence of radiation induced N-related defects in Si. Besides well-known signals of substitutional (Ns) at 653 cm−1, interstitial (Ni) at 691 cm−1, N2 at 766 cm−1, N–O complexes at 801, 996 and 1026 cm−1 and N2O at 973 and 996 cm−1 we determined some additional signals. The pair of bands at 646 and 663 cm−1 has been tentatively correlated with the Ns V pair in agreement with previous theoretical calculations. Similarly the pair of bands at 725 and 778 cm−1 has been tentatively correlated with the N2 V complex and another pair of bands at 930 and 953 cm−1 may be related with the N2SiI complex. Additionally, oxygen-vacancy defects such as the vacancy-oxygen pair (A-center or VO) are common in electron irradiated Si and can impact the material and electronic properties of Si. We investigate and compare the effect of N doping on oxygen-vacancy defects in electron irradiated Si. It is determined that nitrogen reduces the production of VO defects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Si been the main semiconductor material for numerous nanoelectronic, sensor and photovoltaic devices [1–5]. The ever decreasing dimensions of devices makes defect processes very important. Their detailed understanding can impact material and/or device properties and is still not well established for many systems [6–10].

From a technological viewpoint, oxygen (O) impurities are important in electron irradiated Si and their control is necessary to optimise devices. FTIR spectroscopy has been used for many years to investigate the production and annealing behavior of defects in irradiated Si. In previous studies Localised Vibrational Modes (LVM) arising from oxygen-related and carbon-related defects in Si have been assigned to particular defects. The VO defect (also known as the A-center) band at 830 cm−1 has been assigned [11, 12] to the neutral charge state and is the archetypal oxygen-related defect in Si. Upon thermal annealing at elevated temperatures, VO becomes mobile and begins to patricipate in various reactions. Important among them are those involving the addition of oxygen atoms to the initial VO pair leading to the sequential formation of VOn (n > 1) complexes [12, 13]. The first member of the VOn (n > 1) family is the VO2 defect with a well-known IR band associated with it at ~888 cm−1. Another important reaction channel is that involving the addition of vacancies to the initial VO pair leading to the sequential formation of V mO (m > 1) complexes [14, 15]. The first members of this family [14, 15] are the V 2O and the V 3O defects with well-known IR bands at ~825 and ~839 cm−1, respectively. In recent studies oxygen-related defects and their control have been thoroughly investigated [16–18].

More than five decades after the optical detection of N in Si [19], N-related defects are still of interest, due to their impact on intrinsic point defects and defect clusters in Si [20–23]. From a technological viewpont, inspite of their low solubility, N impurities (a) impact the mechanical properties of Si [24, 25], (b) interact with vacancies and affect the size and kinetics of void growth (these cause gate oxide failure) [26], (c) enhance oxygen precipitation [27–30] and form shallow thermal donors with oxygen [24].

Before considering the interaction of N with other defects and impurities, it is important to establish the most stable form of N in the Si lattice. The N substitutional behaves as a deep level impurity and is a trigonally distorted defect with C3υ symmetry [31–33]. In situations when N is present in high concentrations such as the case of hydrogenated amorphous Si, N acts as a donor [34, 35]. Additionally, the diffusion of N in Si has not been fully described, in spite of numerous years of research [36]. The dominant state of N in Si has been found to be the N interstitial pair (N2), both experimentally (IR and channeling experiments) and theoretically [33, 37–39]. The main reasons that N2 is the dominant form, as compared to Ns, are chemical and geometrical [40]. Recent density functional theory (DFT) calculations by Zhu et al. [41] showed that Ni has a low activation energy for diffusion (0.3 eV) and this implies that Ni can easily diffuse even at room temperature and can therefore combine with a vacancy to form Ns or with a Ni atom to form a N2 defect. A small percentage of N (~10 %) possesses an off-center substitutional configuration Ns. The dominant form of N in Si is a N–N pair which gives rise to two IR bands at 766 and 963 cm−1 [32]. DFT calculations have determined that the pair consists of two neighboring 〈100〉 oriented N–Si split interstitials [37], yielding a Ni–Ni structure. Additionally, we note that the Ni center also exists, and a LVM band at 690 cm−1 has been associated with the defect [42]. Thus, N in the IR spectra of irradiated Si is expected to have spectroscopic signatures as Ns, Ni and Ni–Ni.

It is well-known both from experimental and theoretical investigations that N in Si has a tendency to associate with vacancies and self-interstitials (SiI) [31, 36, 38–40, 43, 44]. Indeed, N pairs with a V to form N–V complexes as has been determined through positron annihilation spectroscopy studies in N implanted Si [43]. Oxygen precipitation studies in N-doped Si have concluded that NV pairs function as precipitate nuclei [45] in agreement with first principles thermodynamic calculations [40], which have verified the stability of NV defects. Remarkably, it has been shown theoretically that a N2 V 2 structure is the most stable form of N–V defects [40], and it has also been suggested to act as oxygen precipitate nuclei [39, 46, 47]. On the other hand, N is expected to react with SiI, and the formation of a (Ni)2SiI defect has been studied theoretically [38].

Nitrogen also interacts with other impurities including oxygen [32]. Nitrogen–oxygen complexes have been reported in several experimental and theoretical works [36, 44, 48–54]. IR bands at 1026, 996, 801 cm−1 as well as at 1018 and 810 cm−1 have been associated with nitrogen–oxygen complexes [50].

As a result, when N is present in the Si lattice, it is expected to affect the various reactions that take place upon material processing as thermal treatments, irradiation, etc. For irradiated N-doped Czochralski silicon (Cz-Si), it is of interest to investigate the effect of N on the formation of irradiation defects, their reactions, and their evolution upon annealing. In the present study, we use FTIR to investigate the impact of N on the production of VO defects in electron irradiated Si.

2 Experimental methodology

We used two groups of samples cut from prepolished Cz-Si wafers. One group of Cz-Si samples contained N and the other was N-free for comparison purposes. The N concentrations were given by the provider of the samples. The carbon (606 cm−1) and oxygen (1106 cm−1) concentrations were determined by infrared spectroscopy using calibration coefficients 1.0 × 1017 and 3.14 × 1017 cm−2, respectively [55, 56]. The nitrogen, oxygen and carbon concentrations are given in Table 1. The samples were irradiated with 2 MeV electrons with a fluence of 2 × 1018 cm−2, at about 70 °C, using the Dynamitron accelerator at Takasaki-JAERI (Japan). After the irradiation, all the samples were subjected to 20 min isochronal anneals up to 600 °C in open furnaces with a step of 10 °C. Following each annealing step, IR spectra were recorded at room temperature using an FTIR spectrometer (JASCO-470 plus) with a resolution of 1 cm−1. The two phonon background absorption was subtracted from each spectrum by using a float-zone sample of equal thickness.

3 Results and discussion

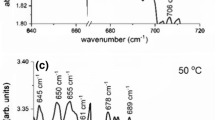

Figure 1 shows IR spectra for the N-doped Si sample Ν95 prior to irradiation, after the irradiation and at a characteristic temperature in the course of the 20 min isochronal annealing sequence ~450 °C, respectively. The insets to the figure show spectral ranges in magnification, in order to have a better picture of the numerous bands appearing in the spectra. Characteristic among them, in the spectra prior to irradiation Fig. 1a, are the bands at 653 cm−1 of Ns, at 691 cm−1 of Ni, at 766 and 963 cm−1 of the N2 pair, at 801 and 996 cm−1 of the N2O complex [36, 50] and at 810 cm−1 of the N2O2 complex [36, 50]. A number of other bands that appear in the spectra are presently unidentified, for example at 645, 673, 756, 925, 1012, 1032 cm−1 and so on. Possibly, the latter two bands at 1032 and at 1012 cm−1 may correspond, respectively, to the 1026 cm−1 band of the N2O structure [36, 50] and the 1018 cm−1 band of the N2O2 structure [36, 50]. On the other hand, in the spectra after irradiation, Fig. 1b, signals appear, in addition to the well-known band of the VO defect [12, 57] at 830 cm−1. Important among them is, for example, a band at 663 cm−1. A band at this wavenumber has been theoretically predicted to originate from the Ns V pair [38]. A very weak band at 646 cm−1 may also be related to the latter defect [38].Moreover, a pair of bands at 725 and 778 cm−1 observed here can be tentatively attributed to the N2 V defect [44]. We note that a LVM frequency at 781 cm−1 was calculated [21] to be related to the N2 V structure. Additionally, another pair of bands at 930 and 953 cm−1 seen in these studies can be tentatively attributed to the N2SiI structure, as theoretical calculations of the LVM frequencies of the latter structure may suggest [38]. Indeed, six LVM frequencies have been calculated to be related to the N2SiI structure and two values around 936.2 and 947.6 cm−1 may correspond to our experimental frequencies at 930 and 953 cm−1. Here, we observe only two peaks out of the six suggested theoretically, however, the signals are very weak and maybe these bands are undetected. In any case further experimental work is necessary to verify the above assignments. After annealing at ~450 °C Fig. 1c, besides the well-known bands [12, 57] of the VO2 defect at 890 cm−1 and the VO3 at 905, 967 and 1000 cm−1, other signals are also present in the spectra. A full account of the bands appearing in the spectra of Fig. 1a–c is reported in Table 2, with an emphasis on the N-related bands [21, 32, 36, 38, 42, 44, 49–51, 58, 59]. Possible identifications of these bands in relation to information appearing in the literature is also included in Table 2 to give a tentative assignments of the defects appearing in the spectra of this experiment.

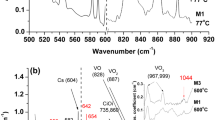

Figure 2 shows the IR spectra of the N-free Cz-Si sample M5 prior to irradiation, after irradiation, and at a characteristic temperature (~450 °C) in the course of the 20 min isochronal annealing sequence, respectively. The spectra are given for comparison purposes with those of the N-doped Si sample. Importantly, the N-free sample contains carbon, and after irradiation, some well-known C and O related bands appear in the IR spectra, for example the band at 865 cm−1 assigned to the CiOi defect, two bands at 936 and 1020 cm−1 assigned to the CiOiSiI complex, a band at 994 cm−1 tentatively assigned to with the CiOsSiI complex, and so on [60–63]. These bands are beyond the scope of the present work. One of the purposes of this study is to investigate the effect of N on the production of the VO defect in Si, and the presence of C in the N-free sample should be taken into account since the latter impurity also affects the formation of the VO defect. The relative discussion will be presented below.

Figure 3 presents Lorentzian profiling of the VO frequency range at some characteristic temperatures both for the N95 (Fig. 3a) and the M5 (Fig. 3b) samples. Besides the 830 cm−1 band of VO defect, two bands at 826 and 839 cm−1 correlated [14, 15] respectively with the V 2O and V 3O defects are observed.

Figure 4 shows the evolution of the V 2O (826 cm−1) (a) and the V 3O (839 cm−1) (b) bands. It is observed that the signals from the V 2O and the V 3O satellite bands are weaker in the N-doped N95 sample. At this stage it is not easy to definitely conclude about the role of N on the formation of the V 2O and the V 3O defects. The observed differences can reflect the influence of C which is present in the M5 sample. Indeed, C readily reacts with SiI allowing for more V to be available after irradiation. This is presumably realized in the spectra by the increase of the vacancy-related defects V 2O and the V 3O in the M5 sample.

Figure 5 shows the evolution with temperature of the VO and the VO2 defects of the N95 and M5 samples. It is observed from Fig. 5 that N doping can limit the formation of VO and VO2 defects. In particular, comparing the spectra of M5 and N95 samples it is estimated that the concentration of VO in the N-doped sample is about 33 % smaller than in the N-free sample. However, the N-free M5 sample contains carbon of ~1017 cm−3. It is well-known that the presence of C in the Si lattice enhances [64, 65] the production of VO. Referring to Fig. 1 of Ref. 64 and assuming a C concentration of ~1016 cm−3 for the N-doped sample, one can calculate that the induced increase of VO is about 4 % for samples irradiated with a fluence of 5 × 1017 cm−2. Since in our case the fluence of irradiation was 2 × 1018 cm−2, i.e. 4 times larger and taking also into account that the VO concentration is proportional to the square root of the fluence [64] the final increase of VO is ~8 %. Consequently the net reduction of VO due to the N presence is approximately ~25 %.

From a theoretical viewpoint calculations based on DFT have shown that the binding energy of N with the V to form the NV pair is 1.6–2.12 eV depending upon the methodology [38]. This value is comparable to the calculated binding energy of 1.32–2.21 eV to form the VO defect [66–70]. The similar binding energies of the NV and VO defects implies that N competes with O in capturing V in irradiated Si. Thus, the NV as well as the N2 V centers are expected to form [38, 40] besides the VO pair. Notably, the N2 V defect is highly bound (4.46 eV). Of course, N concentration is at least three orders of magnitude less than that of O in our Cz-Si samples and it is expected that most of the vacancies produced in the course of irradiation, in particular those avoiding annihilation by self-interstitials or/and those pairing with other vacancies, would pair with O to form VO pairs. However, some V will associate with N atoms leading to the reduction of the VO formation in agreement with the observations in the spectra. Of course, it would be better to compare between a N-doped and a N-free sample. However, in our case the N-free sample contains C making the comparison between the intensities of the VO defects in the two samples more complicated. Nevertheless, from previous studies [64, 65] the effect of C on the VO production was elucidated and the comparison between the two samples was possible. Local strain and/or pressure variations can impact materials properties [71–75] and as such we aim to investigate the effect of the introduction of large N concentrations on the production and stability of related clusters and VO defects in Si.

4 Conclusions

FTIR spectroscopy is employed to investigate the formation of N-related radiation defects as well as the impact of N on the production of VO defects in electron irradiated Si. A number of weak IR bands are tentatively attributed to N-related structures. In particular, two bands at 646 and 663 cm−1 were attributed to a Ns V pair, two bands at 725 and 778 cm−1 were attributed to the N2 V complex and another pair of bands at 930 and 953 cm−1 were attributed to the N2SiI complex. Additional work involving irradiations at higher than 2 × 1018 cm−2 fluences are necessary to verify the above assignments. Indeed, stronger signals will allow the study of the thermal evolution of these defects to allow comparisons with the results from other experimental techniques. Furthermore, the present experimental results determined that N doping can reduce the formation of VO defects. The limitation of these defects will be beneficial as they can deleteriously impact materials properties and in turn the performance of devices.

References

S.G. Cloutier, P.A. Kossyrev, J. Xu, Nat. Mater. 4, 877 (2005)

E. Rotem, J.M. Shainline, J.M. Xu, Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 051127 (2007)

A. Chroneos, H. Bracht, R.W. Grimes, B.P. Uberuaga, Mater. Sci. Eng., B 154–155, 72 (2008)

A. Chroneos, R.W. Grimes, H. Bracht, J. Appl. Phys. 105, 016102 (2009)

C. Gao, X. Ma, J. Zhao, D. Yang, J. Appl. Phys. 113, 093511 (2013)

S. Takeuchi, Y. Shimura, O. Nakatsuka, S. Zaima, M. Ogawa, A. Sakai, Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 231916 (2008)

L.I. Murin, E.A. Tolkachava, V.P. Markevich, A.R. Peaker, B. Hamilton, E. Monakhov, B.G. Svensson, J.L. Lindström, P. Santos, J. Coutinho, A. Carvalho, Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 182101 (2011)

A. Chroneos, C.A. Londos, E.N. Sgourou, J. Appl. Phys. 110, 093507 (2011)

H. Tahini, A. Chroneos, R.W. Grimes, U. Schwingenschlögl, H. Bracht, Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 072112 (2011)

P. Chen, X. Yu, X. Liu, X. Chen, Y. Wu, D. Yang, Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 082107 (2013)

J.W. Corbett, G.D. Watkins, R.S. McDonald, Phys. Rev. 135, A1381 (1964)

C.A. Londos, L.G. Fytros, G.J. Georgiou, Defects Diffus. Forum 171–172, 1 (1999)

L.I. Murin, J.L. Lindstrom, B.G. Svensson, V.P. Markevich, A.R. Peaker, C.A. Londos, Solid State Phenom. 108–109, 267 (2005)

N.V. Sarlis, C.A. Londos, L.G. Fytros, J. Appl. Phys. 81, 1645 (1997)

L.I. Murin, B.G. Svensson, J.L. Lindstrom, V.P. Markevich, C.A. Londos, Solid State Phenom. 156–158, 129 (2010)

A. Chroneos, C.A. Londos, E.N. Sgourou, P. Pochet, Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 241901 (2011)

E.N. Sgourou, D. Timerkaeva, C.A. Londos, D. Aliprantis, A. Chroneos, D. Caliste, P. Pochet, J. Appl. Phys. 113, 113506 (2013)

H. Wang, A. Chroneos, C.A. Londos, E.N. Sgourou, U. Schwingenschlögl, Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 052101 (2013)

W. Kaiser, C.D. Thurmond, J. Appl. Phys. 30, 427 (1959)

H.C. Alt, H.E. Wagner, J. Appl. Phys. 106, 103511 (2009)

F. Sahtout Karoui, A. Karoui, J. Appl. Phys. 108, 033513 (2010)

V.V. Voronkov, R. Falster, J. Appl. Phys. 112, 013519 (2012)

M. Belli, M. Fanciulli, D. Batani, Phys. Rev. B 89, 115207 (2014)

K. Sumino, I. Yonenaga, M. Imai, T. Abe, J. Appl. Phys. 54, 5016 (1983)

M. Akatsuka, K. Sueka, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., Part 1 40, 1240 (2001)

H. Ishii, S. Shiratake, K. Oka, K. Motonami, T. Koyama, J. Izumitani, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., Part 2 35, L1385 (1996)

K. Nakai, Y. Inoue, H. Yokota, A. Ikari, J. Takahashi, A. Tachikawa, K. Kitahara, Y. Ohta, W. Ohashi, J. Appl. Phys. 89, 4301 (2001)

R.F.X. Ma, X. Yu, D. Yang, Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 496 (2002)

D. Yang, J. Chu, J. Xu, D. Que, J. Appl. Phys. 93, 8926 (2003)

N. Fujita, R. Jones, J.P. Goss, P.R. Briddon, T. Frauenheim, S. Öberg, Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 021902 (2005)

K.L. Brower, Phys. Rev. B 26, 6040 (1982)

H.J. Stein, in Oxygen, Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen in Crystalline Silicon, vol. 59, ed. by J.C. Mikkelsen Jr, S.J. Pearton, J.W. Corbett, S.J. Pennycook (MRS, Pittsburg, PA, 1986)

K.L. Brower, Phys. Rev. Lett. 44, 1627 (1980)

Y. Yatsurugi, N. Akiyama, Y. Endo, T. Nozaki, J. Electrochem. Soc. 120, 975 (1973)

J.H. Zhou, K. Yamaghuchi, Y. Yamamoto, T. Shimizu, J. Appl. Phys. 74, 5086 (1993)

X. Yu, J. Chen, X. Ma, D. Yang, Mater. Sci. Eng., R 74, 1 (2013)

R. Jones, S. Öberg, F.B. Rasmussen, B.B. Nielsen, Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 1882 (1994)

J.P. Goss, I. Halm, R. Jones, P.R. Briddon, S. Öberg, Phys. Rev. B 67, 045206 (2003)

H. Sawada, K. Kawakami, Phys. Rev. B 62, 1851 (2000)

H. Kageshima, A. Taguchi, K. Wada, Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 3718 (2000)

Z. Zhu, H. Shao, X. Dong, N. Li, B.-Y. Ning, X.-J. Ning, L. Zhao, J. Zhuang, Sci. Rep. 5, 10513 (2015)

H.J. Stein, Appl. Phys. Lett. 47, 1339 (1985)

L.S. Adam, M.E. Law, S. Szpala, P.J. Simpson, D. Lawther, O. Dokumaci, S. Hegda, Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 523 (2001)

N. Inoue, H. Ohyama, K. Watanabe, H. Seki and Y. Kawamura, in International Conference on Defects in Semiconductors 2013, AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 1583, 19 pp (2014)

A. Karoui, F.S. Karoui, A. Kvit, G.A. Rozgoni, D. Yang, Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 2114 (2002)

A. Taguchi, H. Kageshima, K. Wada, J. Appl. Phys. 97, 053514 (2005)

C. Cui, X. Ma, D. Yang, J. Appl. Phys. 104, 123523 (2008)

H.J. Stein, in Defects in Electronic Materials, vol. 104, ed. by M. Stavola, S.J. Pearton, G. Davies (Materials Research Society, Pittsburgh, PA, 1988)

M.W. Qi, S.S. Tan, B. Zhu, P.X. Cai, W.F. Gu, X.M. Xu, T.S. Shi, D.L. Que, L.B. Li, J. Appl. Phys. 69, 3775 (1991)

D. Yang, D. Que, K. Sumino, Phys. Stat. Sol. B 210, 295 (1998)

V.D. Ahmetov, H. Richter, N. Inoue, Mater. Sci. Eng., B 134, 207 (2006)

P. Wagner, R. Oeder, W. Zulehner, Appl. Phys. A 46, 73 (1988)

A. Gali, J. Miro, P. Deak, C.P. Ewels, R. Jones, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 8, 7711 (1996)

HCh. Alt, Y.V. Gomeniuk, F. Bittersberger, A. Kempf, D. Zemke, Mater. Sci. Semicond. Proc. 9, 114 (2006)

A. Baghdadi, W.M. Bullis, M.C. Choarkin, Y. Li, R.I. Scace, R.W. Series, P. Stallhofer, M. Watanabe, J. Electrochem. Soc. 136, 2015 (1989)

J.L. Regolini, J.P. Stroquert, C. Ganter, P. Siffert, J. Electrochem. Soc. 133, 2165 (1986)

J.W. Corbett, G.D. Watkins, R.M. Chrenro, R.S. McDonald, Phys. Rev. 121, 1015 (1961)

R. Jones, C. Ewels, J. Goss, J. Miro, P. Deak, S. Öberg, F. Berg, Rasmussen. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 9, 2145 (1994)

N. Inoue, M. Nakatsu, H. Ono, Y. Inoue, Mater. Sci. Eng., B 134, 202 (2006)

G. Davies, R.C. Newman, in Handbook of Semiconductors, Materials Properties and Preparations, ed. by T.S. Moss, S. Mahajan (North Holland, Amsterdam, 1994), p. 1557

C.A. Londos, Semicond. Sci. Technol. 5, 645 (1990)

M.S. Potsidi, C.A. Londos, J. Appl. Phys. 100, 033523 (2006)

N. Inoue, H. Ohyama, Y. Goto, T. Sugiyama, Phys. B 401–402, 477 (2007)

C.A. Londos, E.N. Sgourou, A. Chroneos, J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 25, 4872 (2014)

V.V. Voronkov, R. Falster, C.A. Londos, E.N. Sgourou, A. Andrianakis, H. Ohyama, J. Appl. Phys. 110, 093510 (2011)

A. Chroneos, E.N. Sgourou, C.A. Londos, U. Schwingenschlögl, Appl. Phys. Rev. 2, 021306 (2015)

A. Chroneos, C.A. Londos, J. Appl. Phys. 107, 093518 (2010)

M. Pesola, J. von Boehm, T. Mattila, R.M. Nieminen, Phys. Rev. B 60, 11449 (1999)

J. Coutinho, R. Jones, P.R. Briddon, S. Öberg, Phys. Rev. B 62, 10824 (2000)

R.A. Casali, H. Rucker, M. Methfessel, Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 913 (2001)

C.N. Koumelis, G.E. Zardas, C.A. Londos, D.K. Leventouri, Acta Cryst. A 32, 306 (1976)

N.R. Zangenberg, J. Lundsgaard Hansen, J. Fage-Pedersen, A. Nylandsted Laresn, Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 125901 (2001)

R.V. Vovk, M.A. Obolenskii, A.A. Zavgorodniy, A.V. Bondarenko, I.L. Goulatis, A.V. Samoilov, A. Chroneos, J. Alloys Compd. 453, 69 (2008)

R.V. Vovk, Z.F. Nazyrov, M.A. Obolenskii, I.L. Goulatis, A. Chroneos, V.M.P. Simoes, Philos. Mag. 91, 2291 (2011)

H. Tahini, A. Chroneos, R.W. Grimes, U. Schwingenschlögl, A. Dimoulas, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 24, 195802 (2012)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. A. Misiuk (Institute of Electron Technology, Warsaw, Poland) for the provision of the N-doped samples and to Prof. H. Ohyama (Kumamoto National College of Technology, Japan) for the electron irradiations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sgourou, E.N., Angeletos, T., Chroneos, A. et al. Infrared study of defects in nitrogen-doped electron irradiated silicon. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 27, 2054–2061 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-015-3991-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-015-3991-2