Abstract

A thermoresponsive drug delivery system was constructed based on microwave radiation. Core–shell mesoporous silica nanoparticles were synthesized by using ZnO@Fe3O4 nanoparticles as the core for enhancing heat generation under microwave radiation and mesoporous silica as the shell for drug accommodation. A novel short peptide Phe-Phe-Gly-Gly (N-C) with good self-assembly performance was grafted on the surface of mesoporous silica as a nanovalve. The modified peptide on mesoporous silica nanoparticles blocked the drug in the pores at physiological temperature via self-assembling process and opened up the pores for drug release at elevated temperature via disassembling process. The doped ZnO@Fe3O4 nanoparticles core had excellent microwave-absorbing and thermal conversion property. On-demand drug release from this delivery system was realized not only by conventional heating but also by a noninvasive microwave radiation. In vitro results show that local heating generated by the core under microwave radiation was sufficient for release triggering while holding the bulk heating at physiological temperature. The controllable tissue-penetrating microwave stimuli combined with the tailor-made self-assembling peptide offer a new approach for thermal-responsive drug release.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

At present, chemotherapy is still the most effective method to treat malignant tumors [1]. But conventional methods of administration limit drug treatment because many anticancer drugs cannot be directly administered [2, 3]. In order to solve this issue, controlled drug delivery systems (CDDSs) have received much attention and shown good performance [4,5,6]. The ideal CDDSs should keep drug stable with no leakage in transport and release drugs artificially to specific sites. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) with high specific surface area, tunable pore size, low toxicity, and easy-to-modify surface have become one of the most promising carriers in drug delivery systems in recent years [7]. Many MSNs-based CDDSs responding to various stimuli including internal stimuli and external stimuli have been developed for cancer treatment [8,9,10,11,12]. Since internal stimuli depend on the sensitive and uncontrollable biological environment, noninvasive external stimuli including light, ultrasound and magnetic fields have attracted more attention on constructing CDDSs [9, 10, 13,14,15]. Nowadays, the interest in microwave stimulation has been greatly stimulated in many smart drug delivery studies due to its robust properties, such as good thermal efficiency, high tissue penetration depth and controllable operability [4, 16]. Shi et al. [17] have utilized the microwave irradiation to trigger core–shell nanoparticles forming by poly(p-phenylenediamine) and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) with exceptional high efficiency for controlled drug release. Qiu et al. [18] designed a microwave-sensitive drug microcarrier based on Fe3O4@ZnO@mGd2O3:Eu nanoparticles using polymer poly[(N-isopropylacrylamide)-co-(methacrylic acid)] as the microwave stimulus gatekeeper. Since the effect of the bulk heating caused by microwave can be avoided by using a high-frequency short-time microwave instrument, it is very meaningful to construct a MSN-based drug delivery system responding to microwave radiation [19]. The nanoparticles (NPs) chosen to fulfill the drug delivery are based on a mesoporous silica shell surrounding a doped ZnO@Fe3O4 core [iron (II, III) oxide (Fe3O4)]. The core is chosen for its high-performance microwave-absorbing property and the shell of mesoporous silicon for its good biocompatibility and large pore volume for drug loading.

To control the drug release under the microwave heating, a thermosensitive molecular gatekeeper for MSN-based CDDS is necessary. Peptide is selected for its biocompatibility, adjustable physicochemical properties and biological functions [11, 20, 21]. Designed peptides based on building blocks of amphiphilic amino acids which can self-assemble to form stable structure have attracted increasing attentions due to its multifarious potential applications in drug delivery, tissue engineering and cell culture [22, 23]. Considering the controllable self-assembly process and disassembly process under suitable conditions, such as desired temperature, pH, ionic solution or solvent, we proposed that the peptide can be an ideal candidate for a thermosensitive nanovalve on MSNs for on-demand drug loading and release.

Inspired from the well-known diphenylalanine (Phe-Phe), which has excellent self-assembling property, we have designed a self-assembling thermosensitive peptide Boc-Phe-Phe-Gly-Gly-COOH (Boc-P4-COOH) as the nanovalve. The designed peptide Boc-P4-COOH can self-assemble to form stable microstructure at physiological temperature and disassemble at about 50 °C, which can be used as drug loading and releasing by thermotriggering. Taking into account all the above considerations, we proposed core–shell MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 (the core ZnO@Fe3O4 surrounding with mesopore silica shell) modified with a thermosensitive designed peptide to construct a microwave-responsive nanocarrier for drug delivery. As shown in Fig. 1a, we first synthesized the doped core ZnO@Fe3O4, hydrolyzed tetraethyl orthosilicate to form the core–shell particles MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 and then modified with the designed peptide as the gatekeeper. ZnO was doped with Fe3O4 to increase microwave absorption for rapid local heating, while no significant temperature increases on bulk solution. Release experiments were studied with both conventional heating and microwave heating. The data demonstrated that the peptide gatekeeper can block the cargo inside the carrier with little to no leakage without microwave applied, while it can be triggered open by microwave heating. In addition, we found that the nanoparticles modified by polypeptide had an excellent biological compatibility.

a Synthesis of magnetic mesoporous silicon modified by thermosensitive polypeptide and the mechanism of controlled release of thermoresponsive peptide. b Chemical structure of the peptide 1, amino on mesoporous silicon surface 2 and peptide valves 3. Schematic diagram of self-assembly and disassembly of peptides modified on mesoporous silicon. Self-assembly and disassembly of polypeptides were used to block and open pores

Results and discussion

Characterization of Fe3O4 and ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs

Fe3O4 NPs and ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs were obtained by the thermal decomposition method [24]. The morphology of the nanoparticles was characterized by TEM (Fig. 2a, b). From the figures, we can see that the monodisperse Fe3O4 NPs and ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs have successfully been synthesized with particle sizes of about 7.5 ± 1.1 nm and 9.5 ± 0.8 nm, respectively (Figure S1). The size of ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs is slightly larger than that of Fe3O4 NPs, which is caused by the coating of ZnO layer on the outer surface of the Fe3O4 core.

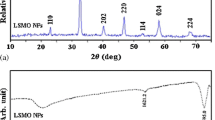

The crystallinity of the nanoparticles was determined by XRD. As shown in Fig. 3a, six major diffraction peaks at 35.0°, 41.3°, 50.4°, 62.9°, 67.2° and 74.1° are observed for the diffraction pattern of Fe3O4 nanocrystals, which can be assigned to (220), (311), (400), (422), (511) and (440) planes of the cubic spinel-structured magnetite, respectively, according to the standard JCPDS (No. 99-0073). For ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs, the peaks of magnetite are observed in the diffraction pattern of the nanocomposites, revealing that the Fe3O4 nanocrystals do not change. The new diffraction peaks at 37.1°, 40.2°, 42.4°, 55.8°, 56.6°, 66.8° and 74.5° can be assigned to the hexagonal ZnO structure according to the standard JCPDS (No. 36-1451).

The obvious lattice fringes in the HRTEM image (Fig. 2d) further confirm the high crystallinity of the sample ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs. The spacing labeled in the shell region is about 0.14 nm, corresponding to the (103) plane of ZnO, and 0.21 nm in the core corresponding to the (400) plane of Fe3O4, which are in good agreement with the wide-angle XRD results. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectrum (EDS) of ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs (Fig. 1e) confirms the copresence of zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) in the ZnO@Fe3O4 samples. The results confirm that ZnO is successfully coated on the Fe3O4 nanoparticle. The Fe:Zn ratio of the ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) is near 3:1.

Figure 3b shows the field-dependent magnetization curves measured at 300 K. Both Fe3O4 NPs and ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs exhibit the behavior of no coercivity and remanence, which confirm that both nanoparticles are superparamagnetic at 300 K. The Fe3O4 NPs possess superparamagnetic properties, and the saturated magnetization is 55 emu g−1, which is lower than theoretical saturated magnetization of bulk Fe3O4 NPs (about 98 emu g−1), due to a large amount of organic ligands such as oleic acid and oleyl amine adhered to the surface of Fe3O4 NPs [25]. Thermogravimetric analysis of Fe3O4 NPs (Figure S3B) also demonstrates that substances adhere to the surface of particles. The saturation magnetization of ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs decreases to 40 emu g−1. The decrease in the saturation magnetization can be attributed to the lower density of the magnetic component in ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs compared with the Fe3O4 NPs. It is noted that the MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles (Figure S2) show some magnetization, which is desirable for separation and further application.

Self-assembling property of designed peptide

The designed peptide Phe-Phe-Gly-Gly (N-C) is selected as a nanovalve for its biocompatibility and self-assembling property. The peptide can self-assemble to form stable secondary structure at physiological temperature and can disassemble at about 50 °C, which make the peptide an ideal candidate for the nanovalve of control release [14].

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) was used to verify the secondary structure of the designed peptide (Fig. 5a). The peak at 1538 cm−1 is due to N–H bending vibrations in plane and C–N stretching vibrations. The band at v = 1670 cm−1 is due to C=O stretching vibrations, which indicate that beta-sheet structure has formed. The band at v = 702 cm−1 is due to the absorption peak of monosubstituted benzene (–C6H5).

Atomic force microscope (AFM) images of the peptide Phe-Phe-Gly-Gly (N-C) at a concentration of 0.2 mg mL−1 in an aqueous solution are shown in Fig. 4. The images reveal that the peptide is able to self-assemble to form fibers. As shown in Fig. 4a, the fibers with height of 37.2 nm and width of 112.8 nm interweaved with each other to form a larger network. Many protofibrils are also detected with height of 1.0 nm and width of 10.9 nm. Combining the data of FTIR and AFM, we proposed that the designed peptide can firstly self-assemble to form stable secondary structure including beta-sheet structure and then to form protofibrils. The protofibrils are bundled to form fibers, which are further connected and knotted with each other to form a relatively dense network. It is this self-assembled property that makes the peptide to be used as a nanovalve to block the pores of magnetic mesoporous silicon.

Characterization of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 nanocarriers

The core–shell MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 nanocarriers were synthesized by a base-catalyzed reaction by sol-gel process on the surface of the ZnO@Fe3O4 core [26]. As shown in TEM of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles (Fig. 2c), the core–shell structure can be clearly distinguished because of the different electron penetrability between the core and the shell. The magnetic cores are black spheres, while the uniform mesoporous silica shells show gray color with an average thickness of about 35 nm with average particles size of 93.8 ± 14.2 nm. The obtained particles are uniform with good monodispersion. Besides, we can clearly see typical mesoporous channels in the silica shell layer.

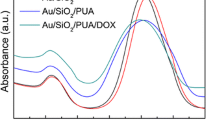

The self-assembling peptide was modified on the surface of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles as the nanovalve via amidation reaction [14]. In order to prove the successful grafting of the designed peptide Boc-P4-COOH onto the surface of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4, FTIR, zeta potential, TGA and BET were utilized. Figure 5a shows the FTIR spectra of Boc-P4-COOH, MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles and Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles, respectively. It can be seen that the corresponding infrared spectra of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles show some differences after modification. A significant peak at 3457 cm−1 presented in all samples is due to the stretching vibration of –OH group. The band at v = 1072 cm−1 is assigned to asymmetric stretching vibration of (Si–O–Si). The bands around 1660 cm−1 in all samples are assigned to –NH2. The absorption peaks of amino groups in all samples are due to the modification of the core by amino groups (Figure S3A). Compared with the spectrum of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4, the appearance of bands at v = 1670 cm−1 and 1538 cm−1 of Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles for C=O stretching vibrations and N–H bending vibrations, respectively, shows that the peptide-modified nanoparticles have the same structure as the designed peptide, suggesting the successful modification of the peptide. The successful grafting is also proved by a new band at v = 702 cm−1 (–C6H5) in the spectrum of Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4.

a FTIR spectra of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles (black), Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles (red) and Boc-P4-COOH (blue). b Zeta potential of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4, NH2-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 and Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles. c Dynamic light scattering of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4, NH2-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 and Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles. The polydispersity of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4, NH2-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 and Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 is 0.08, 0.09 and 0.14, respectively. d Nitrogen adsorption (filled symbols) and desorption (open symbols) isotherms of sample of Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles. Inset: pore size distribution of Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles

The zeta potentials of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4, NH2-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 and Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles in aqueous suspension are − 16.8 ± 0.4, + 22.3 ± 1.2 and + 14.4 ± 0.7 mV at pH = 7.0, respectively (Fig. 5b). MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles present a negative potential of about − 16.8 mV because of the presence of –OH (silanol) group on the MSNs surface. After APTES modification, the surface Si–OH groups are partly replaced by amino group so the zeta potential of NH2-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles becomes positive. The reason why the positive feature decreases after peptide conjugation was mainly due to the presence of protective group (see Fig. 1b for details). The polypeptide grafted onto the surface of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles does not remove the protective group. The change of zeta potentials indicates that we have successfully grafted the molecular valve polypeptide onto the MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4. The hydrodynamic diameter of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles is about 170 nm, which has no significant change compared with NH2-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles (Fig. 5c). The hydrodynamic diameter of the peptide-modified magnetic particles is about 220 nm, which may be due to the decrease of zeta potential. Furthermore, TGA was also used to determine the weight loss of the organic component in the samples. As shown in Figure S4, the weight loss of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles is 11.4% after heating temperature to 800 °C, while it increases to 15.4% after modified by amino group. The main reason of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles weight loss is the evaporation of silicon hydroxyl group. The increased weight loss of the particles after amination is mainly caused by the silane coupling agent. After grafting the peptide Boc-P4-COOH, the weight loss of Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles is 21.0%. Obviously, the content of organic compounds in nanoparticles increases with the modification process, which suggests the success of functionalization. The nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherm of Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles is shown in Fig. 5d. The loop of the sample exhibits typical IV-type isotherms according to the IUPAC classification, which is typical for mesoporous materials. The Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles have a surface area of 572 m2 g−1, a pore diameter of 2.8 nm and a total pore volume of 1.10 cm3 g−1. To note, the modified peptide is not fully blocking the access of nitrogen gas molecule as it might be in open state after drying up sample into powders, whereas when peptide was in closed state, it is efficient enough to block larger drug molecules.

Microwave-absorbing properties and thermal effect properties of the synthesized nanoparticles

It is well known that the heating effect of materials under microwave radiation depends on two key parameters, the real part (ε′) and the imaginary part (ε″) of permittivity. The real part describes the material’s capacity of the electromagnetic energy storing, while the imaginary part describes the efficiency of the electromagnetic energy to heat energy [27]. An increase in ε″ can not only improve the microwave absorption properties of materials, but also make more electromagnetic energy into heat energy [25]. The ratio of the imaginary part to the real part is defined as dielectric loss tangent:

Dielectric loss tangent illustrates the ability of a material to absorb electromagnetic energy and convert it into heat energy at the frequency. Figure 6 shows the real part, the imaginary part of complex permittivity and the dielectric loss tangent of Fe3O4 and ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs. From Fig. 6a, it could be found that the real part of ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs is almost larger than that of Fe3O4 NPs in the frequency range of 2–18 GHz. The large real part of permittivity shows that ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs have a high ability of energy storage. From Fig. 6b, c, it could be found that imaginary part of permittivity and dielectric loss tangent of ZnO@Fe3O4 are larger than those of Fe3O4 at 2.45 GHz which is the frequency for biomedical applications. The data of imaginary part of permittivity and dielectric loss tangent illustrate that the ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs can theoretically convert more electromagnetic energy into heat energy, compared with Fe3O4 NPs.

In order to verify the thermal effect of different nanoparticles, the temperature of the suspension of Fe3O4 NPs, ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs and MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles dispersed in deionized water with the concentration of 0.2 mg mL−1 was detected under microwave irradiation. From the curves in Fig. 7a, we can see that four samples show different microwave thermal effects under the microwave radiation of 50 W. The initial temperature of the suspension is 20 °C. In the first 10 s, there is almost no difference among the samples except sample of ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs, while the heating effect of the sample of ZnO@Fe3O4 is significantly higher than that of other samples. After 10 s, the heating effect of the sample of Fe3O4 NPs and sample of ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs is significantly higher than that of other samples, which indicate that Fe3O4 NPs and ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs have excellent microwave thermal effect. The temperature of suspensions can increase to 78 °C and 92 °C in 70 s under microwave heating, respectively, for Fe3O4 and ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs. The results show that sample of ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs has superior microwave thermal efficiency and can convert electromagnetic energy into heat energy quickly. It is worth noting that the temperature of sample MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles is almost the same as that of deionized water. MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles have only a slight effect on heating of bulk solution under microwave radiation. The heat generated by the core of MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles is mainly for local heating.

a Microwave thermal response of the time-dependent temperature curve for deionized water, Fe3O4 and ZnO@Fe3O4 NPs, MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles dispersed in deionized water with microwave irradiation. b Microwave thermal response of the time-dependent temperature curve for deionized water, MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles dispersed in deionized water with microwave irradiation after adding the ice water circulating cooling system

Thermosensitive property via release study by conventional heating

The hydrophilic fluorescein was selected as a model drug in drug delivery study due to its stability and suitable size. The loading experiments were carried out by mixing the dye and the nanoparticles at 50 °C for 2 h. The high temperature used for dye loading was to make sure that the modified peptide would not self-assemble to block the pore. The loaded particles were then placed at room temperature holding overnight for pore blocking via the self-assembling process of the modified peptide. Then fluorescein-loaded nanoparticles were washed many times with deionized water to remove the un-trapped fluorescein molecules. When the fluorescein could not be detected in the supernatant after centrifugation, washing process was finished.

To insure that the self-assembling peptide was thermosensitive and could act as a gatekeeper for MSNs-based drug delivery system, we first carried out the drug release experiments with Boc-P4-MSNs with conventional heating via water bath. The release experiments were carried out at 37 °C and 50 °C for 10 h, respectively (called bulk heating). The release curves are shown in Fig. 8a. The release of the dye can be triggered by the temperature of 50 °C. The release rate is approximately 34.9% at 50 °C for 10 h, while there is almost no fluorescent releasing at 37 °C. The result indicates that the thermosensitive peptide can block the pore effectively at physiology temperature and release the drug by pore opening at 50 °C.

Thermosensitive property via release study by microwave heating

In order to confirm that the drug release could also be triggered by microwave heating, we carried out the drug release experiments with Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles under microwave irradiation. The loading and washing processes for the core–shell nanoparticles were similar to those used for Boc-P4-MSNs (refer to electronic support materials for specific steps).

Considering the bulk heating of microwave radiation, an ice water circulating cooling system was set for temperature controlling. The temperature of pure deionized water and the suspension of Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles under microwave radiation with the same power and the same frequency were detected, and the results are shown in Fig. 7b. It can be seen that the temperature of both solutions can be successfully controlled at about 37 °C during microwave radiation. The system was used for subsequent release under microwave heating.

In this section, the drug release experiment was divided into two stages. Firstly, the dye release was measured at a constant temperature of 37 °C using water bath heating for 1 h. It is almost impossible to detect fluorescent substances in the solution in first-hour release of bulk heating, indicating the excellent blocked property of the self-assembling peptide at 37 °C, which is coincided with the previous results. Then, the release experiment was carried out under microwave radiation. The release container was alternatively placed in microwave radiation field for 10 min, followed by stirring at room temperature for 15 min without microwave irradiation to ensure uniform dispersion of fluorescent substances. The dye release was detected by spectrum monitor. A cooling system with circulating ice water was used to maintain the temperature of bulk solution around 37 ± 1 °C for avoiding the effect of bulk heating. As shown in Fig. 8b, the concentration of fluorescein significantly increases under the microwave irradiation, indicating that the nanovalve can be triggered by microwave irradiation. With increase in time, the release increases and approximately 32.5% of loaded dye is released after eleven heating/stirring cycles. It clearly demonstrates that the dye is effectively blocked in the channels of the nanoparticles by the modified peptide at physiological temperature and can be triggered release from the carrier under microwave radiation. Since the bulk heating is maintained by the cooling system, we suggest that the thermal effect generated by the local heating of the core under microwave irradiation can open the thermosensitive nanovalve of the self-assembling peptide.

In vitro studies of cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles was investigated by an MTT assay using African green monkey SV40-transformed kidney fibroblast cells (COS7) (Fig. 9). COS7 cells were cultured with Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles at a concentration ranging from 6 to 200 μg mL−1. From Fig. 9, we can see that COS7 cells have a high survival rate after 48 h of culture at both low and high concentrations of Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles. At the maximum concentration of 200 μg mL−1, the viability of COS7 cells can reach 82%. High cell viability in all tests indicates that the Boc-P4-MSN@ZnO@Fe3O4 particles have no cytotoxicity in the concentration range tested.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have designed and synthesized a kind of thermoresponsive drug delivery system based on core–shell mesoporous silica nanoparticles grafted with self-assembling peptide. The core–shell nanoparticles chosen to fulfill the drug delivery are based on a mesoporous silica shell for drug loading surrounding a doped ZnO@Fe3O4 core for enhancing heat generation. The iron oxide nanoparticles coated with zinc oxide layer have demonstrated excellent microwave-absorbing and thermal conversion property and could generate sufficient local heating under microwave radiation for triggering the thermosensitive nanovalve. The designed peptide with good self-assembly performance at physiological temperature could be trigged to disassemble by the local heating of microwave radiation, which was utilized here as a nanovalve for pore blocking and opening. In this paper, a new method of thermal-responsive drug release was proposed: A self-assembling thermosensitive peptide was selected as the nanovalve, and the nanovalve could be triggered by the local heating of ZnO@Fe3O4 cores under microwave radiation, while the bulk solution is at physiological temperature. The combination of the controllable tissue-penetrating microwave stimuli and the tailor-made self-assembling peptide presents a new method for thermal-responsive drug release.

Supplementary materials

Reagent and characterization; Synthesis process; Specific steps of the experiments; Figure S1 to Figure S5.

References

Wang F, Hu S, Sun Q, Fei Q, Ma C, Lu C, Nie J, Chen Z, Ren J, Chen G-R, Yang G, He X-P, James TD (2019) A leucine aminopeptidase-activated theranostic prodrug for cancer diagnosis and chemotherapy. ACS Appl Bio Mater. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.9b00655

Khadka P, Ro J, Kim H, Kim I, Kim JT, Kim H, Cho JM, Yun G, Lee J (2014) Pharmaceutical particle technologies: an approach to improve drug solubility, dissolution and bioavailability. Asian J Pharm Sci 9(6):304–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajps.2014.05.005

Chen W, Cheng CA, Lee BY, Clemens DL, Huang WY, Horwitz MA, Zink JI (2018) Facile strategy enabling both high loading and high release amounts of the water-insoluble drug Clofazimine using mesoporous silica nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 10(38):31870–31881. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b09069

Jin Y, Liang X, An Y, Dai Z (2016) Microwave-triggered smart drug release from liposomes co-encapsulating doxorubicin and salt for local combined hyperthermia and chemotherapy of cancer. Bioconjug Chem 27(12):2931–2942. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00603

Karimi M, Sahandi Zangabad P, Ghasemi A, Amiri M, Bahrami M, Malekzad H, Ghahramanzadeh Asl H, Mahdieh Z, Bozorgomid M, Ghasemi A, Rahmani Taji Boyuk MR, Hamblin MR (2016) Temperature-responsive smart nanocarriers for delivery of therapeutic agents: applications and recent advances. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 8(33):21107–21133. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b00371

Cully M (2016) Drug delivery: nanoparticles improve profile of molecularly targeted cancer drug. Nat Rev Drug Discov 15(4):231. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2016.60

Pan L, He Q, Liu J, Chen Y, Ma M, Zhang L, Shi J (2012) Nuclear-targeted drug delivery of TAT peptide-conjugated monodisperse mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc 134(13):5722–5725. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja211035w

Ruehle B, Clemens DL, Lee BY, Horwitz MA, Zink JI (2017) A pathogen-specific cargo delivery platform based on mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc 139(19):6663–6668. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b01278

Ruhle B, Datz S, Argyo C, Bein T, Zink JI (2016) A molecular nanocap activated by superparamagnetic heating for externally stimulated cargo release. Chem Commun (Camb) 52(9):1843–1846. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5cc08636a

Lee SF, Zhu XM, Wang YX, Xuan SH, You Q, Chan WH, Wong CH, Wang F, Yu JC, Cheng CH, Leung KC (2013) Ultrasound, pH, and magnetically responsive crown-ether-coated core/shell nanoparticles as drug encapsulation and release systems. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 5(5):1566–1574. https://doi.org/10.1021/am4004705

Xiao D, Jia HZ, Ma N, Zhuo RX, Zhang XZ (2015) A redox-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticle capped with amphiphilic peptides by self-assembly for cancer targeting drug delivery. Nanoscale 7(22):10071–10077. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5nr02247a

Chen H, Kuang Y, Liu R, Chen Z, Jiang B, Sun Z, Chen X, Li C (2018) Dual-pH-sensitive mesoporous silica nanoparticle-based drug delivery system for tumor-triggered intracellular drug release. J Mater Sci 53(15):10653–10665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-018-2363-8

Qiu M, Wang D, Liang W, Liu L, Zhang Y, Chen X, Sang DK, Xing C, Li Z, Dong B, Xing F, Fan D, Bao S, Zhang H, Cao Y (2018) Novel concept of the smart NIR-light-controlled drug release of black phosphorus nanostructure for cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115(3):501–506. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1714421115

Ruan L, Chen W, Wang R, Lu J, Zink JI (2019) Magnetically stimulated drug release using nanoparticles capped by self-assembling peptides. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b13614

Ding Y, Zhu Y, Wei S, Zhou J, Shen J (2019) Cancer cell membrane as gate keeper of mesoporous silica nanoparticles and photothermal-triggered membrane fusion to release the encapsulated anticancer drug. J Mater Sci 54(19):12794–12805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-019-03788-y

Bu Y, Cui B, Zhao W, Yang Z (2017) Preparation of multifunctional Fe3O4@ZnAl2O4:Eu3+@mSiO2–APTES drug-carrier for microwave controlled release of anticancer drugs. RSC Adv 7(87):55489–55495. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ra12004d

Shi Y, Ma C, Du Y, Yu G (2017) Microwave-responsive polymeric core–shell microcarriers for high-efficiency controlled drug release. J Mater Chem B 5(19):3541–3549. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7tb00235a

Qiu H, Cui B, Zhao W, Chen P, Peng H, Wang Y (2015) A novel microwave stimulus remote controlled anticancer drug release system based on Fe3O4@ZnO@mGd2O3:Eu@P(NIPAm-co-MAA) multifunctional nanocarriers. J Mater Chem B 3(34):6919–6927. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5tb00915d

Xu J, Cheng X, Tan L, Fu C, Ahmed M, Tian J, Dou J, Zhou Q, Ren X, Wu Q, Tang S, Zhou H, Meng X, Yu J, Liang P (2019) Microwave responsive nanoplatform via P-selectin mediated drug delivery for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with distant metastasis. Nano Lett 19(5):2914–2927. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b05202

Cheng YJ, Zhang AQ, Hu JJ, He F, Zeng X, Zhang XZ (2017) Multifunctional peptide-amphiphile end-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for tumor targeting drug delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 9(3):2093–2103. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b12647

Chen G, Xie Y, Peltier R, Lei H, Wang P, Chen J, Hu Y, Wang F, Yao X, Sun H (2016) Peptide-decorated gold nanoparticles as functional nano-capping agent of mesoporous silica container for targeting drug delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 8(18):11204–11209. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b02594

Dasgupta A, Das D (2019) Designer peptide amphiphiles: self-assembly to applications. Langmuir 35(33):10704–10724. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b01837

Ruan L, Zhang H, Luo H, Liu J, Tang F, Shi Y-K, Zhao X (2009) Designed amphiphilic peptide forms stable nanoweb, slowly releases encapsulated hydrophobic drug, and accelerates animal hemostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:5105–5110

Lavorato G, Lima E, Vasquez Mansilla M, Troiani H, Zysler R, Winkler E (2018) Bifunctional CoFe2O4/ZnO core/shell nanoparticles for magnetic fluid hyperthermia with controlled optical response. J Phys Chem C 122(5):3047–3057. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b11115

Ji J, Huang Y, Yin J, Zhao X, Cheng X, He S, Li X, He J, Liu J (2018) Synthesis and electromagnetic and microwave absorption properties of monodispersive Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 composites. ACS Appl Nano Mater 1(8):3935–3944. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b00703

Albayatı SHM, Deveci P (2019) pH and GSH dual responsive smart silica nanocarrier for doxorubicin delivery. Mater Res Exp. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab0cde

Parkes GMB, Barnes PA, Charsley EL, Bond G (1999) Microwave differential thermal analysis in the investigation of thermal transitions in materials. Anal Chem 71(22):5026–5032. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac990760w

Acknowledgements

Thanks to associate professor Qian Chen for her suggestions on the microwave absorption properties of particles and Dr. Fang Wang for her assistance in the measurements of AFM. Thanks to Xiangrui He and Manxin Ru for their help in the experimental process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Z., Yang, C., Li, R. et al. Microwave thermal-triggered drug delivery using thermosensitive peptide-coated core–shell mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J Mater Sci 55, 6118–6129 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-04428-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-04428-6