Abstract

A series of Ce1−x Fe x O2 (0 < x ≤ 0.5) catalysts were prepared by the co-precipitation method, and their catalytic performances were investigated for the total oxidation of CO and CH4 as model reactions. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Raman spectroscopy results show that Ce1−x Fe x O2−δ solid solutions are formed with x ≤ 0.2. Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 solid solution presents superior catalytic performance for CH4 and CO oxidation, while Ce1−x Fe x O2 with x > 0.2 shows less active for CO and CH4 oxidation. The results of H2-temperature programmed reduction (H2-TPR), CH4-temperature programmed surface reaction (CH4-TPSR) and CO-TPSR reveal that, the surface oxygen of catalyst is relevant to CO oxidation, which was promoted by the oxygen vacancies formed in Ce–Fe–O solid solution, while the easier lattice oxygen migration property and the favorable reducibility of the catalysts is responsible for the promoted catalytic performance for CH4 oxidation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The catalytic combustion of methane and CO oxidation has been studied extensively in recent decades owing to the energy utilization and environmental requirements. For the total oxidation of methane and CO oxidation, the supported noble metal catalysts present an excellent activity [1, 2]. However, the noble metal catalysts are not fully satisfactory owing to the high price and scarce resources. Recently, the ceria-based catalysts have drawn much attention as a substitute or part substitute for the noble metal catalysts owing to their low cost and good performance for the oxidation reaction [3, 4]. Ceria (CeO2) has been widely used as a promoter of the catalysts or an oxidation catalyst because of its unique redox property and high oxygen storage capacity [4, 5]. The important role of ceria in the catalytic oxidation reactions is the generation and participation of surface oxygen species and anionic vacancies in the catalytic reactions [6].

It is well known that the redox property and the lattice oxygen mobility of CeO2 can be profoundly improved by the substitution of Ce4+ with other trivalent ions (Pr3+ and Tb3+) or smaller homovalent ions (Zr4+) [7, 8]. Given the effects of trivalent ion and smaller size on the structure and properties of ceria, considerable scientific interest is focused on introducing Fe3+ ions into the ceria lattice [9]. It was found that Fe substitution of Ce in CeO2 can distort the sublattice oxygen to promote an activation of lattice oxygen, which is responsible for the better CO oxidation [10]. It has been reported that the mesoporous Ce–Fe mixed oxides present good performance for total oxidation of methane owing to a generation of oxygen vacancies and moderate pore sizes [11]. As an oxygen carrier, the CeO2–Fe2O3 complex oxides can directly transform methane to synthesis gas by using the lattice oxygen [12]. Li et al. [13] also reported that the chemical interaction between surface iron sites and the Ce–Fe solid solution strongly enhances the reducibility of the Ce–Fe–O materials, and methane tends to be activated on the surface iron sites as the carbonaceous species and hydrogen.

For the CH4 combustion or CO oxidation, whether the Ce–Fe–O solid solution behaves better performance than the CeO2–Fe2O3 complex oxide, was reported relatively rarely. Moreover, the influence of Ce–Fe–O solid solution formation on the redox property of CeO2–Fe2O3 complex oxide and the active sites of the Ce–Fe–O solid solution catalyst for methane catalytic combustion and CO oxidation need be illuminated further.

In this paper, the Ce–Fe–O solid solutions were prepared by the co-precipitation method, and their structure and catalytic properties for the CH4 and CO oxidation were evaluated. The effect of the iron concentration on the properties of the solid solutions has been studied in detail. The difference of the properties between the Ce–Fe–O solid solution and its complex oxides has been discussed based upon the results of structural, redox properties and the catalytic performance.

Experimental

Catalyst preparation

Ce1−x Fe x O2 (x = 0–0.5, atomic percent) composite oxides were prepared by the co-precipitation method [9]. Ce(NO3)3·6H2O (0.03 mol) and Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (0–0.015 mol) were solved in de-ionized water. The synthesis solution above and 10 wt% ammonia aqueous solution were simultaneously added drop by drop to a precipitating batch containing 200 mL de-ionized water under stirring. After the pH value of synthesis solution reached 8–9, it was heated to 70 °C under stirring and kept for 4 h. Subsequently, the precipitates were filtered and washed with successive de-ionized water, dried at 110 °C overnight and calcined at 600 °C for 4 h in air. After calcination, the solid powder was pressed and crushed to 40–60 mesh. The pure CeO2 and Fe2O3 were prepared by similar procedures described above.

Catalyst characterization

The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were performed on a Rigaku D/max 2250VB/PC diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured at 77 K with a NOVA 4200e Surface Area and Pore Size Analyzer. Before measurements, the samples were outgassed at 180 °C under vacuum for 4 h. The surface areas of samples were calculated by the Brumauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. The Raman spectra were obtained on a Renishaw Raman spectrometer equipped with a CCD detector at ambient temperature and moisture-free conditions. The emission line at 514.5 nm from an Ar+ ion laser (Spectra Physics) was focused, analyzing spot about 0.01 cm, on the sample under the microscope. The Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) absorption spectra were recorded on a Nicolet NEXUS 670 FT-IR spectrometer with 32 scans at an effective resolution of 4 cm−1. The sample to be measured was ground with KBr and pressed into thin wafer for analysis.

H2-temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) of samples was conducted with a thermo-conductivity detector (TCD). 50 mg sample was loaded in the U-shaped quartz tube reactor. 10%H2/N2 mixture gas of 45 mL min−1 was used at ambient pressure and the heating rate was 10 °C min−1. CH4-temperature-programmed surface reaction (CH4-TPSR) and CO-TPSR of samples were performed in a quartz micro-reactor. 100 mg catalyst in the reactor was pretreated at 500 °C for 30 min in 50 mL min−1 20%O2/He mixture gas. After the sample was cooled to the room temperature, the sample was heated from the room temperature to 750 °C in 50 mL min−1 of 1%CH4/He (or 2% CO/He) at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. The outlet gas was analyzed by a quadrupole mass spectrometer (INFICON Transpecter 2). The signals of CH4, CO, CO2 were recorded at the m/z = 15, 28 and 44, respectively.

Testing of catalytic activity

The catalytic activity of the Ce1−x Fe x O2 catalyst for CO (or CH4) oxidation was tested in a quartz tube microreactor with 100 mg catalyst at atmospheric pressure. The feed gas was consisted of 1% CO and 10% O2 (or 1% CH4 and 4% O2) balanced by Ar. The flow rate was 50 mL min−1, and space velocity (SV) was 30000 mL g−1 h−1. The reactants and products were analyzed online by gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with TCD.

Results and discussion

Textural and structural properties

The XRD patterns of Ce1−x Fe x O2 mixed oxides are shown in Fig. 1. For Ce1−x Fe x O2, only diffraction peaks of cubic ceria are observed as x ≤ 0.2, and with an increase in Fe content (x > 0.2) the α-Fe2O3 diffraction peaks appear just. After adding Fe in CeO2, the CeO2 (111) peak shifts toward higher diffraction angles and the lattice parameters of ceria decrease from 0.5377 to 0.5332 nm (Table 1), which indicates that the Ce1−x Fe x O2−δ solid solution has been formed after smaller size Fe3+ (0.64 Å) substitutes for Ce4+ (0.97 Å) inside the cubic phase CeO2 structure [14], and the oxygen vacancies in CeO2 tend to be formed owing to the charge balance. F. J. Pérez-Alonso et al. [9] also reported that cubic ceria-like (Fe in CeO2) and hematite-like (Ce in Fe2O3) solid solutions can be formed when Fe content is high (Fe/(Ce + Fe) ≥ 0.5) in the samples calcined at 300 °C, and the cubic ceria-like solid solution structure would be destroyed, after calcination at higher temperature (such as 500 °C).

The BET surface areas of Ce1−x Fe x O2 mixed oxides are shown in Table 1. It is found that the surface area increases obviously with the introduction of Fe in CeO2. However further increase in the Fe content from 0.1 to 0.5 leads to the decrease of its BET surface area from 63.6 to 18.3 m2 g−1.

Figure 2 shows the Raman spectra of all samples. For all Ce1−x Fe x O2 samples, a broad band with relatively high intensity at ~465 cm−1 and a weak band at 1180 cm−1 are observed, which are ascribed to the F2g vibration mode and primary A1g asymmetry of CeO2, respectively [15], indicating the existence of cubic CeO2 structure. The band at ~600 cm−1 is linked to lattice defects resulted from the produced oxygen vacancies in the ceria fluorite structure [16]. With the Fe addition in CeO2, the band ascribed to the F2g mode of CeO2 shifts slightly to lower wave number region as shown in the enlarged graphic in Fig. 2, which should be attributed to the formation of Ce1−x Fe x O2 solid solution with Fe ion replacing Ce ion in CeO2 lattice, and the nanosized sample in current study [17]. The Fe2O3 sample exists the characteristic peaks of α-Fe2O3: A1g at 500 cm−1, Eg at 407 and 612 cm−1, and second harmonic vibration at 1317 cm−1 [18]. With an increase in Fe content, the intensity of band at 1317 cm−1 enhances obviously, and the band at 1194 cm−1 decreases conversely, indicating the formation of α-Fe2O3 on the surface of solid solution. Therefore correlated with XRD results, it shows that only a small part of Fe3+(x < 0.2) can be incorporated into the ceria lattice, resulting in the oxygen vacancy formation; with an increase of Fe content in CeO2–Fe2O3 sample, α-Fe2O3 has been formed in the sample.

Catalytic performances for CH4 and CO oxidation

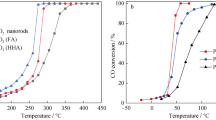

The catalytic performances of Ce1−x Fe x O2 for CH4 and CO oxidation are shown in Fig. 3 and the corresponding light-off temperatures are listed in Table 1. In the CH4 catalytic combustion reaction, CH4 can be totally oxidized to CO2 and H2O, and the catalyst activity is improved obviously because of an addition of Fe in CeO2. When x = 0.1, the sample exhibits superior activity, the reaction temperature of 50% CH4 conversion (T 50) is 484 °C. While further increasing Fe amount from 0.1 to 0.5 gradually leads to the decrease of the catalytic activity. It should be noted that pure Fe2O3 shows good performance, almost comparable to the performance of Ce0.2Fe0.8O2. Bulk iron oxide has been studied as an alternative catalyst for CH4 combustion, because of its good activity [19]. For CO oxidation, the presence of Fe in ceria can obviously improve the catalytic activity, when x = 0.1, Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 catalyst exhibits superior catalytic activity, such as T 10 = 125 °C and T 50 = 188 °C. However, its activity decreases with an increase of Fe content in the sample. Pure CeO2 and Fe2O3 show poor activity for CO oxidation.

The results above show that Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 solid solution has an excellent activity for CH4 and CO oxidation, and changing Fe content in Ce1−x Fe x O2 can affect obviously its catalytic activity. Meanwhile, pure Fe2O3 exhibits better catalytic performance than pure CeO2 in the CH4 oxidation and CO, especially for the deep oxidation of CH4.

H2-TPR testing

The H2-TPR profiles of CeO2, Fe2O3, and Ce1−x Fe x O2 mixed oxides are shown in Fig. 4. For Fe2O3, there is a sharper peak at 377 °C and a broad band at ~650 °C with two overlapping peaks, which are corresponding to the reduction of hematite (Fe2O3) to magnetite (Fe3O4) and magnetite to Fe0, respectively [20]. In the H2-TPR profile of CeO2, two peaks are observed at ~510 and 784 °C, which should be assigned to the reduction of surface and bulk oxygen, respectively [21]. For Ce1−x Fe x O2 mixed oxides, more complex TPR profiles are obtained, involving more reduction peaks [14]. In the H2-TPR profiles of Ce1−x Fe x O2 (x ≤ 0.2) solid solution samples, α peak at 350–400 °C is attributed to the reduction of Fe3+ inside Ce–Fe–O solid solution and β peak at 600–650 °C should be ascribed to the reduction of Fe2+, and the peak at >700 °C should be because of the reduction of bulk Ce4+. With an increase in Fe amount (x > 0.2), two additional peaks appear between α and β peaks, which should be assigned to the reduction of aggregated Fe2O3 on the sample surface. The rise of reduction temperature of α and β peaks may be explained by the decreased oxygen vacancy in CeO2 as shown in Raman spectra, resulting in the low reducibility of ceria. As shown in Fig. 4b, the low temperature reduction peaks at <380 °C should be attributed to the reduction of surface oxygen species [22], which shift to higher temperature with an increase of Fe amount in the samples. Moreover, the larger intensity of the peaks at <380 °C in Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 sample supports the fact that more oxygen species could adsorb on the samples because of larger surface area.

In order to evaluate the redox property of the mixed oxides, after H2-TPR run, the sample was re-oxidized at 600 °C in O2 (20 mL min−1) for 0.5 h, then H2-TPR of sample was carried out again. The H2-TPR profiles of CeO2, Fe2O3, Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 and Ce0.5Fe0.5O2 for continuously two times are plotted in Fig. 5. After one cycle of reduction–oxidation, Fe2O3 exhibits two small reduction peaks at 505 and 625 °C in the TPR profiles, and the high-temperature peak disappears after two cycles of reduction–oxidation. For pure CeO2, three TPR curves are almost the same, which shows that the redox property of CeO2 is not affected by the treatment of reduction–oxidation and the large reduction peak at >800 °C should be ascribed to the consumption of H2 by bulk oxygen in CeO2 [23].

After repeated reduction/oxidation, the low temperature reduction peak of Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 solid solution is located at ~465 °C, and that of Ce0.5Fe0.5O2 is at ~540 °C. For the pure Fe2O3 and CeO2, the low temperature reduction peaks are located at higher temperature of ~505 and ~540 °C, respectively. It can be found that Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 has lower temperature reduction peak after the cycle of reduction/oxidation, which indicates the formation of Ce–Fe–O solid solution by Fe incorporating the CeO2 lattice can improve the oxygen ability of the sample, resulting in better redox property of the Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 sample. Furthermore, the reduction peak area at ~465 °C of Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 solid solution is larger than that at ~505 °C of Fe2O3. Based on the XRD results, it is suggested that for the sample with high Fe content, Fe2O3 remained on the surface would debase the reducibility of catalyst. Therefore, it could be concluded that the facile redox property and the lattice oxygen mobility of CeO2 can be profoundly enhanced by the formation of Ce–Fe–O solid solution with proper amount of Fe doped into CeO2.

CO-TPSR and CH4-TPSR testing

CO-TPSR-MS and CH4-TPSR-MS testing over pure CeO2, Fe2O3 and Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 were carried out after the samples were pretreated in 20% O2 at 500 °C for 1 h, and the results are shown in Fig. 6. It shows from Fig. 6 that CO and CH4 consumption is accompanied by CO2 formation.

For the CO-TPSR profiles, over CeO2, small amount of CO2 are formed at 200–500 °C (Fig. 6a) and over Fe2O3, the oxidation of CO occurs at 250–350 °C, with the top temperature of CO2 forming at 308 °C (Fig. 6b); over the Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 solid solution, there are two consumption peaks of CO with the top temperatures of 175 and 280 °C (Fig. 6c). Relating to the T50 results of CO oxidation in Table 1, T50 is resemble to the top temperature of low temperature reduction peak in the CO-TPSR profiles of Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 and Fe2O3; however, a weak broad plateau of CO2 formation of CeO2 is observed, with T50 of CO oxidation located in the middle of this plateau. Combined with the TPR results, it should be suggested that the CO consumption peaks of Ce0.9Fe0.1O2, Fe2O3 and CeO2 should be ascribed to the reduction of surface oxygen species including the absorbed oxygen and surface lattice oxygen.

The CH4-TPSR profile of CeO2 is similar to that of Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 solid solution, and there is a weak broad plateau of CO2 desorption at 400–650 °C in the former and in the latter at 350–700 °C. It is indicated that the doping of Fe in CeO2 promotes its lattice oxygen mobility and makes the oxygen reduction facile, resulting in the benefiting of CH4 oxidation. In the CH4-TPSR profile of Fe2O3, two CH4 consumption peaks are observed, with very weak at 380–520 °C and at 655 °C, respectively. Relating to the T50 (499 °C) of CH4 oxidation over Fe2O3, the first weak peak is contributed to the activity of Fe2O3 for the oxidation of CH4.

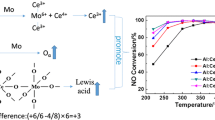

Discussion about the catalytic activity of Ce–Fe–O solid solution

Compared with the pure CeO2, Fe2O3 and CeO2–Fe2O3 mixed oxide with high Fe content, the Ce–Fe–O solid solution shows better catalytic activity for the CH4 and CO oxidation. The formation of Ce–Fe–O solid solution can increase obviously the surface area of ceria, and promote the redox property of the sample. With further increase of the Fe content in Ce1−x Fe x O2 (x > 0.2), the redox property and the surface area of catalyst decline severely, resulting in activity decrease for the oxidation reaction. The density functional theory (DFT) calculations [10] showed that the oxygen sublattice was highly distorted in Fe doped CeO2 which led to formation of long and short M–O (M = Fe, Ce) bonds, and the presence of longer oxygen bonds could improve an activation of lattice oxygen. As shown in XRD and Raman results, only a small part of Fe3+ (x < 0.2) in Ce1−x Fe x O2 sample can be incorporated into the ceria lattice to form a solid solution. As x > 0.2, part of Fe in the form of iron oxide would aggregate on the sample surface and block the oxygen activation of M–O bond, resulting in a decrease in the redox property. Moreover, the iron oxide formed on the sample surface would lower the surface area, which would also debase the activity of the catalysts.

It is well-known that, an increase of the oxygen storage capacity and bulk oxygen mobility of ceria-based catalysts can effectively promote hydrocarbons oxidation reactions [24], and the surface oxygen is benefit to CO oxidation over CeO2 related catalysts [25]. Therefore, the improving performance of Ce–Fe–O solid solution for the CH4 oxidation should be because of the promoted oxygen mobility and the facile redox property of the Ce–Fe–O solid solution. The H2-TPR and CO-TPSR results reveal that more surface oxygen species (including the adsorbed oxygen and active sublattice oxygen) induced by the oxygen vacancy formation and the distorted lattice oxygen for the Ce–Fe–O solid solution, would contribute to the CO oxidation.

Conclusions

The Ce–Fe–O solid solution was prepared successfully by the simultaneous precipitation method. The concentration of Fe in the Ce1−x Fe x O2 sample affects remarkably on the formation of the solid solution and its catalytic performance. As x < 0.2, the Ce–Fe–O solid solution can be obtained; as x > 0.2, part of Fe is incorporated into CeO2 lattice and the rest leaves in the form of iron oxide on the surface of sample. The Ce0.9Fe0.1O2 solid solution exhibits superior catalytic activity for the CH4 and CO oxidation. With an increase of Fe amount in the sample, its catalytic activity declines gradually. The formation of Ce–Fe–O solid solution obviously enhances the redox property and increases the surface areas, which should contribute to CH4 oxidation. And the more surface oxygen species formed in the solid solution are propitious to CO oxidation.

References

Zwinkels MFM, Jaras SG, Menon PG (1993) Catal Rev Sci 35:319

Choudhary TV, Banerjee S, Choudhary VR (2002) Appl Catal A Gen 234:1

Gu C, Miao J, Liu Y, Wang YQ (2010) J Mater Sci 45:5660. doi:10.1007/s10853-010-4631-0

Wang XH, Lu GZ, Guo Y, Jiang LZ, Guo YL, Li CZ (2009) J Mater Sci 44:1294. doi:10.1007/s10853-009-3275-4

Trovarelli A, de Leitenburg C, Boaro M, Dolcetti G (1999) Catal Today 50:353

Trovarelli A, de Leitenburg C, Llorca J, Dolcetti G (1995) J Catal 151:111

Cao JL, Deng QF, Yuan ZY (2009) J Mater Sci 44:6663. doi:10.1007/s10853-009-3582-9

Trovarelli A (1999) Comments Inorg Chem 20:263

Pérez-Alonso FJ, López Granados M, Ojeda M, Terreros P, Rojas S, Fierro JLG, Gracia M, Gancedo R (2005) Chem Mater 17:2329

Gupta A, Kumar A, Waghmare UV, Hegde MS (2009) Chem Mater 21:4880

Liu CW, Luo LT, Lu X (2008) Kinet Catal 49:676

Li KZ, Wang H, Wei YG, Yan DX (2010) Chem Eng J 156:512

Li KZ, Wang H, Wei YG, Yan DX (2010) Appl Catal B Environ 97:361

Perez-Alonso FJ, Melián-Cabrera I, López Granados M, Kapteijn F, Fierro JLG (2006) J Catal 239:340

Weber WH, Hass KC, McBride JR (1993) Phys Rev B 48:178

Mcbride JR, Hass KC, Poindexter BD (1994) J Appl Phys 76:2435

Spanier JE, Robinson RD, Zhang F, Chan SW, Herman IP (2001) Phys Rev B 64:245407

de Faria DLA, Silva SV, de Oliveira MT (1997) J Raman Spectrosc 28:873

Barbosa AL, Herguido J, Santamaria J (2001) Catal Today 64:43

Voskoboinikov TV, Chen HY, Sachtler WMH (1998) Appl Catal B Environ 19:279

Tang X, Zhang B, Li Y, Xu Y, Xin Q, Shen W (2004) Catal Today 93:191

Hu YP, Jin HF, Liu JR, Hao DS (2000) Chem Eng J 78:147

Galvita V, Sundmacher K (2007) J Mater Sci 42:9300. doi:10.1007/s10853-007-1872-7

Terribile D, Trovarelli A, de Leitenburg C, Primavera A, Dolcetti G (1999) Catal Today 47:133

Sayle TXT, Parker SC, Catlow CRA (1994) Surf Sci 316:329

Acknowledgments

This project was supported financially by National Basic Research Program of China (2010CB732300), National Natural Science Foundation of China (20973058, 20601008) and National Key Technologies R & D Program of China (2007BAJ03B01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qiao, D., Lu, G., Liu, X. et al. Preparation of Ce1−x Fe x O2 solid solution and its catalytic performance for oxidation of CH4 and CO. J Mater Sci 46, 3500–3506 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-011-5256-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-011-5256-7