Abstract

The purpose of this article is to establish a typology of entrepreneurship for OECD countries over the 1999–2012 period. Our aim is to draw a distinction between managerial and entrepreneurial economies, to identify groups of countries with similar economic and entrepreneurial activity variables, and to determine the economic and institutional drivers of entrepreneurial activities in each group. We show that the level of development, sectoral specialization, and institutional variables related to entrepreneurship, functioning of the labor market, and openness of the country are decisive to understand differences in entrepreneurship activity across countries. Results show that the pre-crisis period, from 1999 to 2008, is a period of growth favorable to entrepreneurship. The financial crisis involved a break in entrepreneurial dynamism, with agricultural economies withstanding the financial crisis better. The 2010–2012 period of recovery is a period of a sharp slowdown in entrepreneurial activity, during which the countries that are less dependent on the financial sector proved to be the most resilient in terms of entrepreneurial activity. Nevertheless, it is the advanced knowledge economies with developed financial markets, fewer institutional regulatory constraints, and greater scope for qualitative entrepreneurship that show lower unemployment rates. These findings have important implications for the implementation of public policy in order to promote entrepreneurial activity and reduce unemployment.

Résumé

L’objectif de cet article est d’élaborer une typologie des activités entrepreneuriales des pays de l’OCDE durant la période 1999–2012. Notre intention est d’établir une distinction entre les économies managériales et entrepreneuriales, d’identifier des groupes de pays ayant des comportements économiques et entrepreneuriaux similaires et d’identifier les déterminants économiques et institutionnels des activités entrepreneuriales dans chaque groupe. Nous montrons que le niveau de développement, la spécialisation sectorielle ainsi que les variables institutionnelles liées à l’entrepreneuriat, au fonctionnement du marché du travail et à l’ouverture du pays sont déterminants pour appréhender les différences nationales en matière d’activité entrepreneuriale. Les résultats montrent que la période antérieure à la crise, 1999–2008, est une période de croissance favorable à l’entrepreneuriat. La crise financière a provoqué une rupture du dynamisme entrepreneurial; ce sont les économies agricoles qui ont le mieux résisté à la crise financière. La période de reprise 2010–2012 est une période de fort ralentissement de l’activité entrepreneuriale, durant laquelle les économies dépendant largement du secteur financier sont les plus affectées par la crise en terme d’activité entrepreneuriale. Néanmoins ce sont les économies avancées de la connaissance caractérisées par des marchés financiers développés, peu de contraintes institutionnelles de régulation et un entrepreneuriat de qualité qui affichent les taux de chômage les plus faibles. Ces résultats ont des implications importantes pour la mise en œuvre des politiques publiques visant à promouvoir l’entrepreneuriat et à réduire le chômage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Summary highlights

Contributions

This study contributes to existing literature in four ways: first, it proposes a better understanding of the complex relationships between level of development, entrepreneurial dynamics, growth and unemployment, at a country level; second, it determines the economic and institutional drivers of entrepreneurial activities in managerial/entrepreneurial economies; third, it proposes a dynamic approach to entrepreneurship with a sample studied over a 13-year period (including the financial crisis) and appropriate methods; fourth, it suggests recommendations for the implementation of public policy in order to promote entrepreneurial activity and reduce unemployment.

Research questions and purpose

This article addresses the following research questions: first, how can we characterize economies as regards their entrepreneurial activity, taking into account level of development, growth, and unemployment? Second, what are the drivers— economic and institutional regulatory constraints— of entrepreneurial activity at the country level? Third, what is the impact of the financial crisis on entrepreneurial activity?

Basic research methodology and information

Following a quantitative approach, we propose a classification of OECD countries relative to variables pertaining to entrepreneurial activity, growth, and labor market situation. A combined use of multidimensional evolutive data analysis allows us to identify groups of countries with similar entrepreneurship behavior. Thanks to supplementary variables representative of economic development and institutional environment, the classification is enriched and the different kinds of development highlighted.

Results/findings

Results indicate that: first, the level of development, sectoral specialization, and institutional variables related to entrepreneurship, functioning of the labor market, and openness of the country are determinant to understand differences in entrepreneurship activity across countries; second, the pre-crisis period, from 1999 to 2008, is a period of growth favorable to entrepreneurship; third, the financial crisis involved a break in entrepreneurial dynamism with the agricultural economies that have best withstood the financial crisis; fourth, the 2010–-2012 period of recovery is a period of a sharp slowdown in entrepreneurial activity, during which the countries that are less dependent on the financial sector proved to be the most resilient; fifth, in this period, advanced knowledge economies, with developed financial markets, fewer regulatory institutional constraints, and scope for qualitative entrepreneurship, have lower unemployment rates.

Limitations

A possible limitation is that the study only addresses regulatory institutional factors.

Theoretical implications and recommendations

From a theoretical implication point of view, this study provides a better understanding of the components of the national environment (level of development and institutional environment) that promote or deter entrepreneurship, and contributes to explaining the differences between managerial and entrepreneurial economies.

Practical implications and recommendations

From a practical implication perspective, this study provides a useful picture of the economic and institutional conditions that enable an economy to foster opportunity-driven entrepreneurship and reduce unemployment.

Policy recommendations

Four institutional incentives to stimulate entrepreneurship are presented and explained in the paper. It appears that policymakers should: first, alleviate some constraints on entrepreneurship and the functioning of the labor market; second, foster the country’s openness; third, adopt measures to strengthen the national competitiveness and attractiveness of factors of production; fourth, regulate the financial sector.

Future research directions

Future studies should broaden the range of institutional variables investigated, especially considering those relative to informal institutions. Further, a promising direction for future research would be to analyze interactions between entrepreneurship, economic development, and institutional environment in an econometric framework using panel data techniques. Moreover, the use of recent developments in the econometrics of non-stationary panel data would make it possible to analyze both short- and long-run relationships.

Introduction

Audretsch and Thurik (2000, 2001) and Thurik (2011) distinguish two broad analytical models of national economies according to which stylized economic facts can be reinterpreted and reordered. The managerial model articulates economic growth around mass production, specialization, certainty, predictability, and homogeneity, allowing the full play of economies of scale. The model of the entrepreneurial economy articulates economic growth around a variety of needs, as well as novelty, turbulence, innovation, and networking, allowing the full play of entrepreneurial flexibility. The entrepreneur thus becomes an essential vector of growth. Entrepreneurial firms (young and innovative firms) are an integral part of the transition process from an industrial-based economy to an entrepreneurial-based economy and have been the engine of economic growth for over a decade (Bonnet et al. 2010). Many of the new entrepreneurial firms are the creators and leaders of new industries. Most job-creating firms are new and fast-growing, and evidence indicates that the trend towards an entrepreneurial society is accelerating. Aghion (2014) points out that innovation involves a creation/destruction process much like the one embodied in the Schumpeterian entrepreneur and that some countries are better able to “surf” on new waves of innovation such as information technology and communication, “cloud computing,” and renewable energy. In most countries, the real contribution of entrepreneurship to economic development is emphasized by the observation that “Entrepreneurship is considered to be an important mechanism for economic development through employment, innovation and welfare effects” (Acs and Amoros 2008, p. 121). Entrepreneurial activity varies greatly from one country to another over time. Economic development and the institutional environment are major factors that can drive and shape entrepreneurial activity. When one wishes to analyze entrepreneurship from a perspective of international comparisons between countries, one must take into account that countries differ both in their level of development and their regulation of the economy.

The level of development explains why the level of entrepreneurial activity is different among countries. The weight of the primary sector and the functioning of the informal economy explain the high rate of entrepreneurial activity in developing countries. GEMFootnote 1 studies gather countries according to their main engine for growth: factor-driven economies for the less developed ones, efficiency-driven economies for the medium class, and innovation-driven economies for the more developed ones. Observations, collected by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor consortium, have been translated into a U-shaped curve linking countries’ GDP per capita and rate of entrepreneurial activity (Carree et al. 2007). “Total Early stage Entrepreneurial Activity ratesFootnote 2 (TEA) tend to be highest in the factor-driven group, decreasing with higher levels of economic development” (GEM 2015–2016, p. 18). As noticed by Lucas (1978), with the development of and increase in wage opportunities (i.e., the level of the actual wage increases), a diminution of entrepreneurial activity is observed. Nevertheless, according to Naudé (2010), entrepreneurship remains essential for structural change, contributing to the transformation of agricultural economies into knowledge and service economies.

Based on institutional theory—the view that institutions drive the behavior of firms and individuals (North 1990; Scott 1995)—a number of studies have highlighted the importance of the institutional environment to explain differences in entrepreneurial activity between countries. Indeed, institutional factors such as national culture (Mueller and Thomas 2000; Mitchell et al. 2002) and government regulation (Storey 1991; Verheul and Van Stel 2007; Acs et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2017) can promote or deter entrepreneurship in a society. Institutions regulate the behavior of both firms and individuals in an institutional setting and provide an environment in which they can operate. Thus, the regulatory framework and economic policies not only create rules for organizations and individuals but also determine the difficulty of and incentives for starting a business (Bruton and Ahlstrom 2003; Valdez and Richardson 2013).

The aim of this paper is to analyze entrepreneurial activity in OECD countriesFootnote 3 over the period 1999–2012, in order to propose a typology of entrepreneurship within these countries. Our intention is to draw a distinction between managerial and entrepreneurial economies, to identify groups of countries with similar entrepreneurship behavior and to determine the economic and institutional drivers of entrepreneurial activities in each group. We postulate, according to the assumptions of Audretsch and Thurik (2000, 2001), that entrepreneurial economies are more able to deal with a high rate of growth and a low rate of unemployment; so, we combine these variables with the level of development to build a conceptual model of development. Then, we test its relevance empirically. The approach adopted rests on a combined use of multidimensional evolutive data analyses that take into account the characteristics of the countries in terms of four variables: GDP growth, unemployment rate, share of entrepreneurial activity, and the growth of this share. According to the similarity of these four variables, we can establish a classification of OECD countries. Then, we illustrate the different types of development with a set of variables related to economic development and institutional environment, these latter focusing on the regulatory framework.

Our study contributes to explaining the complex relationships between the level of development, entrepreneurial dynamics, growth, and unemployment. It differs from the existing literature on several points. First, thanks to the length of the period being considered and the original methods used, we are able to propose a dynamic analysis of entrepreneurship. Moreover, as our data period ends in 2012, we can study the impact of the financial crisis on entrepreneurial activity. Second, we consider a wide range of variables characteristic of both economic development and institutional regulation to consolidate and enrich our typology of OECD entrepreneurship.

Several important outcomes emerge from this study. First, the financial crisis involved a break in entrepreneurial dynamism. The effects of the financial crisis are noticeable in 2009, after a delay. Second, we provide evidence that the pre-crisis period, from 1999 to 2008, was a period of growth favorable to entrepreneurship. Over this period, we distinguish different kinds of entrepreneurial and managerial economies. Third, our results show that the variables representative of economic development, and in particular those relating to development level and to sectoral specialization, are important to enrich the typology. Moreover, the institutional variables linked to entrepreneurship, functioning of the labor market, and openness of the country also help to sharpen the description of the classes. Finally, mainly because of the financial crisis, the entrepreneurial dynamics vary greatly across countries over the 1999–2012 period. We are able to establish common trajectories for a number of them.

In the following section, we present a brief review of the literature. In “Data and preliminary analysis,” we describe the data and highlight a break in the dynamics of entrepreneurship since the global financial crisis. “Dynamic regional development and typologies of OECD countries” presents typologies of regional development in OECD countries over three periods: before, during, and after the financial crisis. “Conclusion” presents main results and policy implications.

Literature review and conceptual model

Many macroeconomic and institutional causes can explain the differences in entrepreneurial intensity between countries and areas. These all concern what W.J. Baumol names in an important 1990 paper “the rules of the game,” i.e., the structure of reward in the economy. He notes that certain societies have historically presented rather unfavorable structures of reward in the development of entrepreneurship. These structures have diverted the national or local elites from the exercise of the entrepreneurial function and proved indirectly harmful to the diffusion of technical progress (ancient Rome with the valorization of political office, medieval China with the Mandarin system, etc.). Although small and new businesses have usually been important for economic vibrancy, employment growth, and wealth creation in almost all the world economies (Craig et al. 2003), one might observe that certain differences may still be at work regarding the potentiality of growth for new firms and that these differences might amount to different “rules of the game.” The level of development is also important as regards entrepreneurial intensity.

This section provides a brief overview of relevant literature to explain differences in entrepreneurship activity between countries. First, we present the literature related to institutional environment. Second, we refer to the wide literature highlighting the link between entrepreneurial activity and economic development. Finally, based on the differences in development level and entrepreneurial activity, we propose a conceptual model presenting different types of development.

Institutional environment

For economic institutionalists and following North (1990), “the relevant framework is a set of political, social, and legal ground rules that fixes a basis for production, exchange, and distribution in a system or society” (Bruton and Ahlstrom 2003). Scott (1995) distinguishes three institutional categories: regulatory, normative, and cognitive. North (1990) proposes to split institutions into formal and informal. The most formal institutions are the regulatory institutions representing standards provided by laws and other sanctions (Bruton and Ahlstrom 2003). Normative institutions are less formal or codified and define the roles or actions that are expected of individuals. Cognitive institutions relate more to the cultural, behavioral, and role models shared in society. Recent research (Acs et al. 2014) proposes a systemic approach to entrepreneurship via the definition of different national systems of entrepreneurship: “A National System of Entrepreneurship is the dynamic, institutionally embedded interaction between entrepreneurial attitudes, ability, and aspirations, by individuals, which drives the allocation of resources through the creation and operation of new ventures.” Regarding entrepreneurship, the rules of the game include the development and the operation of the financial system, the intensity of the administrative barriers, the legislation regulating labor market relations, the fiscal rules, the social security system, legal consequences of the failure of the firm, the entrepreneurial spirit, and the collective perception of the failure of the firm as well as the perception of success as an entrepreneur (Bonnet et al. 2011). A number of recent studies have explored the impact of the institutional environment on entrepreneurship activity (for example, Pinho 2017), but they differ not only in the choice of the institutions they focus on but also as regards which institutional variables seem to be the most salient ones. Bosma and Schutjens (2011) point out the importance of institutional factors in explaining variations in regional entrepreneurial attitude and activity. Considering different components of entrepreneurial attitudes—i.e., fear of failure in starting a business, perceptions of start-up opportunities, and self-assessment of personal capabilities to start a firm—they argue that institutional conditions influence entrepreneurial behavior not directly but indirectly, firstly by affecting entrepreneurial attitudes. Nissan et al. (2011) find that “institutions affect economic growth, specifically formal institutions, such as procedures or time needed to create a new business, indicating that regulation can influence the context in which entrepreneurship affects economic growth.” Van Stel et al. (2007) examine the relationship between regulation and entrepreneurship in 39 countries and show that a minimum capital requirement for starting a business does seem to lower entrepreneurship rates across countries, while administrative procedures such as time, cost, or the number of procedures needed to start a business do not. Using GEM aggregated survey data of individuals at national level, Valdez and Richardson (2013) show that normative and cultural-cognitive institutions are the main drivers of entrepreneurship. Pinho (2017) underlines that the importance of several institutional dimensions differs between countries driven by production versus countries driven by innovation. Simón-Moya et al. (2014) suggest that both formal and informal institutions matter: countries with high levels of economic freedom and education tend to have more opportunity entrepreneurship. Using cross-sectional data on 42 countries over the 2000–2005 period, Sambharya and Musteen (2014) show that market openness, regulatory quality (for example time and funds consumed by complying with complex regulatory requirements to set up a firm), and some elements of entrepreneurial culture (uncertainty avoidance, institutional collectivism, and power distance) explain the level of opportunity-versus necessity-driven entrepreneurial activity. Zwan et al. (2016) confirm that business owners motivated by opportunity and business owners motivated by necessity have very different profiles along three dimensions: socioeconomic characteristics, personality, and perceptions of entrepreneurial support. Their findings suggest that the impact of institutional factors varies depending on the type of entrepreneurship activity. Aparicio et al. (2016) find that informal institutions, namely control of corruption and confidence in one’s skills, have a higher impact on opportunity-driven entrepreneurship than formal institutions such as number of procedures to start a new business and private coverage needed to get credit.

The empirical literature strongly supports that the three institutional pillars (regulatory, normative, cognitive) can be viewed as important drivers of entrepreneurial activity and contribute to explaining both intensity (level and rate) and motives (necessity or opportunity) of entrepreneurship, as well as the differences between countries. Yet while all the institutional variables have proved to be relevant in understanding the determinants of entrepreneurial activity, those related to regulatory institutions deserve particular attention because they are likely to be controlled by policymakers in order to promote entrepreneurship.

Economic development

GEM reports (2002, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2011, and 2013) highlight a high rate of entrepreneurship in countries whose economic development is relatively low. The weight of the primary sector and the functioning of the informal economy explain the high level of entrepreneurial activity in developing countries. Nevertheless, there is also an impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth that depends on the nature of the entrepreneurial activities and especially on the motives for setting up a firm (opportunity- vs. necessity-driven). For example, Du and O’Connor (2017) show that particularly new product entrepreneurship or improvement-driven opportunity entrepreneurship significantly contribute to the improvement of national level efficiency. According to Szerb et al. (2013, p. 22), “as an economy matures and its wealth increases, the emphasis of industrial activity shifts towards an expanding services sector […]. The industrial sector evolves and experiences improvements in variety and sophistication. Such a development would be typically associated with increasing research and development and knowledge intensity, as knowledge-generating institutions in the economy gain momentum. This change opens the way for development of entrepreneurial activity with high aspirations.” Wennekers et al. (2010) argue “that the reemergence of independent entrepreneurship is based on at least two ‘revolutions’”: the rise of solo self-employment (Bögenhold and Fachinger 2008; Bögenhold et al. 2017; Fachinger and Frankus 2017) which is important for societal and flexibility reasons, and the ambitious and/or innovative entrepreneurs (Acs et al. 1999; Van Stel and Carree 2004; Audretsch 2007). Simón-Moya et al. (2014) argue that necessity-driven entrepreneurship plays a more relevant role in countries whose economic development is relatively low and where inequality prevails. Conversely, in more developed countries with relatively low income inequality and low levels of unemployment, rates of entrepreneurial activity are significantly lower, necessity-driven entrepreneurship is less prevalent, and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is dominant. According to Sambharya and Musteen (2014), “opportunity-driven entrepreneurship often involves more intensive creative processes while necessity entrepreneurship often relies on imitation of well-known business models.” Both are necessary when considering emerging and developing countries. Yet in the case of advanced economies, a high ratio of opportunity- to necessity-driven entrepreneurship is recorded, reflecting a flexible economy more prone to enhance growth. According to Van Stel et al. (2005), the Total Entrepreneurial Activity rate for the 1999–2003 period in 36 countries shows a positive and significant impact on economic growth. Nevertheless, this impact must be differentiated according to the level of development and the development process of the respective countries. It is less important in transition economies (for example, in Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia) and it may even have a negative impact on economic growth in some developing countries (for example in Mexico). The absence of large companies in these countries, as well as a low actual wage, may explain why people tend to favor the choice to become an entrepreneur, as it is sometimes the only means to earn a living.

It is well established that economic development and entrepreneurial activities are closely linked and that less developed countries show a higher entrepreneurial activity. Indeed, for example, Martinez-Fierro et al. (2016) demonstrate that there is a relation between the characteristics of the entrepreneurial environment and the country’s stage of economic development. Economic development modifies both the weight and nature of self-employment, contributes to the growth of wage employment at the expense of self-employment, and leads to sectoral specialization towards a knowledge and service economy. The economy moves towards qualitative entrepreneurship and fosters opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. Therefore, in order to understand the differences in the intensity and nature of entrepreneurial activity between countries, it is necessary to consider both the variables relating to the level of development and the sectoral specialization of countries.

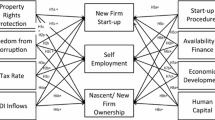

The conceptual model

This paper seeks to throw more light on the combination of the structural type of an economy and certain institutional dimensions, in explaining complex relationships between level of development, entrepreneurial dynamics, growth, and unemployment. We propose a conceptual model that takes into account the level of development of the country, the share of self-employment (as a measure of the entrepreneurial activity), the level of unemployment, and the rate of growth of GDP (as measures of performance of an economy) (Fig. 1). We take into account the structural effect of development by considering low, medium, and high levels of development. The combination of the share of the self-employed in the workforce, along with rates of unemployment and rates of GDP growth, then allows us to identify six theoretical types of development.

Because it is a cyclical variable, the growth of the self-employment share does not directly intervene in the typology of the theoretical types of development presented below; however, it remains an important variable in our study, since it helps to identify the reactions to macroeconomic fluctuations in terms of entrepreneurial characteristics, especially in times of crisis, and it sheds light on the entrepreneurial environment of different economies and its role in overcoming difficulties. Moreover, this variable also makes it possible to identify the refugee/Schumpeter effects in different classes. It is indeed relevant to conceptualize the entrepreneurial choice to start a new venture with the well-known refugee/Schumpeter effects (Thurik et al. 2008; Abdesselam et al. 2014). According to the refugee effect, unemployment may induce new-firm start-ups. Increasing unemployment reduces the opportunity cost of entrepreneurship and consequently stimulates entrepreneurship. The refugee effect is sometimes called the shopkeeper effect. Contrastingly, the Schumpeter effect conveys the fact that new-firm start-ups, launched for opportunity motives, may contribute to the reduction of unemployment (Thurik et al. 2008; Koellinger and Thurik 2012). So, motives related to the start-up of firms stand for different potentialities in terms of growth and employment creation. For example, using cross-sectional data on the 37 countries participating in GEM 2002, Wong and Autio (2005) show that among the different types of entrepreneurial activities, only high-growth-potential entrepreneurship is found to have a significant impact on economic growth.

Acs (2006) describes different stages of development. The first is “marked by high rates of non-agricultural self-employment. Sole proprietorships—i.e., the self-employed—probably account for most small manufacturing firms and service firms. Almost all economies experience this stage.” In terms of the share of self-employment, we consider that this share is rather high for low- and medium-developed countries and this for two main reasons: the agricultural specialization (Kuznets 1966, Syrquin 1988) and the lack or insufficient development of firms that offer wage work (Lucas 1978). The second stage is marked by decreasing rates of self-employment alongside the increase of the average firm size: “marginal managers find they can earn more money while being employed by somebody else” (Acs 2006). Yet, the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth also depends on the nature of the entrepreneurial activities and refers to the difference between an entrepreneurial society which develops private initiative and a wage-based society which increases the opportunity cost to undertake new ventures. For example, for highly developed countries a “rather” low share of self-employment may be translated into low level of unemployment and high growth if the firms are opportunity-driven, while it is the contrary in the case of necessity-driven motives. In the third stage, Acs (2006) explains the revival of entrepreneurship in the most developed countries (although service firms are smaller, they are numerous and have a great importance in GDP and employment share; information and communication technologies increase the returns to entrepreneurship for all firms) and finally justifies the U-shaped relationship between entrepreneurial activity and economic development in the global economy. By definition, for highly developed countries with a high share of self-employment, rates of unemployment are rather low because self-employment supersedes unemployment (Acs 2006). We can then describe our typology:

Path A corresponds to developing countries that are still waiting for take-off. The high share of self-employment is mainly related to the low opportunities for a wage job. A theoretical explanation based on managerial skills and the level of actual wage can be found in Lucas (1978). This path should not be retained, because countries belonging to the OECD cannot be regarded as low-developed countries.

Path B sheds light on developing countries in transition towards becoming developed countries. A priori, Push entrepreneurs are numerous, even though Naudé (2010) observes that in some developing countries there also exists entrepreneurship for opportunity motives—since there is so much to do in these countries in order to catch up with the more developed ones—and there is room for imitative entrepreneurship (Koellinger 2008). Poland could illustrate this case. Since it joined the EU in May 2004, Poland has become one of the most dynamic economies of Europe with an average GDP growth rate of 4.3% over the 2004–2012 period.

Path C comprises entrepreneurial economies issuing from medium development economies that are at the end of the transition phase towards becoming developed countries. The Czech Republic could illustrate this case. It was one of the most stable and prosperous countries in the former Communist countries. In the beginning of the nineties, the privatization of the Czechoslovak economy by Václav Klaus enjoyed a broad political consensus. The Czech Republic presents the most industrialized and developed economy from among the emerging countries of Central Europe, with high growth rates of GDP.

Path D relates to advanced knowledge and service economies where the relatively low level of the share of self-employment is indicative of a mature economy, and so the unemployment rate is rather low. In these countries, innovation accounts for 30% of economic activity, and very often small and innovative entrepreneurial firms operate as “agents of creative destruction.” Nevertheless, the growth in the self-employed share of the workforce is rather weak because the more mature economies undergo development that is more based on qualitative entrepreneurship. Schumpeter effects are more prone to be observed in these countries. The US is representative of this class: in this country, the institutional and cultural environment is more favorable to opportunity motives. According to Acs and Szerb (2007), the federal policy has led to a transition towards an entrepreneurial capitalism (versus managerial capitalism), giving more attention to individuals. For example, the fiscal policy promotes good returns on entrepreneurship, universities give incentives to enhance commercialization of new ideas by researchers, and the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) reserves 2.5% of federal R&D funds for small innovative enterprises.Footnote 4 All things equal, in comparison to France, the US registers three times as many new-firm start-ups that employ at least one salaried worker at the beginning.

Path E corresponds to managerial economies where a low level of entrepreneurship is associated with a high level of unemployment and a low level of growth. It illustrates the reverse version of the Schumpeter effect. For example, in the case of France, several explanations may be put forward for the low intensity of entrepreneurship and the factors deterring “pull” motives: an education inadequate for furthering creativity and entrepreneurship (Retis 2007), the slow development of incubators and an under-development of seed money and private financing networks (Aernoudt 2004), a lack of entrepreneurial spirit (CGPME 2005), the existence of sunk costs for elites (Bonnet and Cussy 2010), and a high unemployment rate that mainly induces entrepreneurship for “push” motives (Abdesselam et al. 2014; Aubry et al. 2014a, b). Obviously, one of the conditions for risk-taking is to be able to find a job again quickly in case of failure and/or to give value to one’s experience. This implies that unconstrained entrepreneurship is favored in economies characterized by a low rate of unemployment, even if an unemployed position generates a low opportunity cost for new entrepreneurs. Empirically, Wennekers (2006) has established a negative relation between the unemployment rate and the rate of entrepreneurial activity in the European case. This result corroborates the fact that the fluidity of the labor market encourages entrepreneurship for opportunity motives while rigidities in the labor market generate entrepreneurship for necessity motives but decrease total entrepreneurship globally.

Path F comprises entrepreneurial economies in highly developed countries with more extensive development based on competitiveness and attractiveness of production factors. Australia and New Zealand may represent this class. In these countries, barriers to entrepreneurship are low, immigration is positive, and trade is important.

Data and preliminary analysis

In this section, we describe the data. Then, we show evidence of a break in the dynamics of entrepreneurship following the global financial crisis.

The data

Our proposal aims to establish a classification of OECD countries thanks to variables related to economic and entrepreneurial activity, namely GDP rate of growth (GDP), unemployment rate (UNEMPL), the self-employed share as a percentage of the working age population (SEMPLShare), and the rate of growth in the self-employed share of the workforce (SEMPLGrowth). According to the OECD, “The number of self-employed is the number of individuals who report their status as ‘self-employed’ in population in labor surveys. Self-employment jobs are those jobs where the remuneration is directly dependent upon the profits (or the potential for profits). The incumbents make the operational decisions affecting the enterprise, or delegate such decisions while retaining responsibility for the welfare of the enterprise.”Footnote 5 In the case of the UK, Faggio and Silva (2012) show that in urban areas, self-employment is strongly and positively linked to other measures of entrepreneurship like business start-ups and innovative firms which are salient aspects of entrepreneurship. This is not the case in rural areas where push entrepreneurs are more numerous. Nevertheless self-employment is often used as a proxy for entrepreneurship, especially for international comparison, even if there is a comparability issue across OECD countries related to the classification of the incorporated self-employed workers. While in official statistics for most OECD countries the self-employed workers who incorporate their businesses are counted as self-employed, in some countries, they are counted as employees (for example, Japan, New Zealand and Norway).

To better understand entrepreneurship, we retain two variables on self-employment which represent both structural (SEMPLShare) and situational components (SEMPLGrowth). In addition, using the growth rate of the self-employed share of the workforce partially overcomes the problem of comparability of self-employed shares series. We use an annual data basis over the 1999–2012 period.

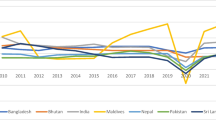

These countries may be considered to be relatively homogeneous, i.e., countries driven by market economies and mostly belonging to innovation-driven economies.Footnote 6 In order to study the dynamics of entrepreneurship in OECD over the 1999–2012 period, we only consider countries for which active variables are available over the whole period. For reasons of data availability and incomplete data, we retain 26 of the 35 countries that are currently members of the OECD, excluding Latvia, Estonia, Greece, Iceland, Israel, Korea, the Slovak Republic, Switzerland, and Turkey. The data are extracted from OECD databases. In Fig. 2, the average evolution of the UNEMPL, GDP, SEMPLShare, and SEMPLGrowth variables is represented for the 26 OECD countries under study for the whole period.

The number of self-employed as a percentage of the population is slightly decreasing with a steady curve during the period, while the rate of growth of the self-employed share is of course more volatile—and always negative—with a decrease from 1999 to 2001, followed by an increase during the 2001–2004 period—a less important decrease—and again a decrease in the year 2005, followed by an increase till 2007 and a decrease in 2008 and 2009, with a final increase till 2011 and a decrease in the last year of observation. The rate of GDP growth sharply decreases from 2007 onwards with a very negative level in 2009. There is a recovery in 2010 but a decrease again in 2011 and 2012. After the crisis of 2008–2009, we can observe a sizeable increase in the unemployment rate.

Moreover, in order to better characterize classes, we use a wide set of illustrative variables relevant for characterizing the context of entrepreneurship in the different countries. These variables are likely to depict different types of developments, so they were positioned as supplementary variables in the multidimensional analysis. They do not affect the calculations based upon the four variables UNEMPL, GDP, SEMPLShare, and SEMPLGrowth: they are not used to determine the principal component factors but are, a posteriori, positioned in order to assess their degree of similarity with the active variables. These variables provide useful information to consolidate and enrich the interpretation of the classes of countries. We consider three categories of variables, representative of national economic development and institutional environment as well as variables specific to the entrepreneurial population. The level of development is usually evaluated by GDP/capita. Due to the imperfection of this measure, it is more appropriate to evaluate it as a combination of a set of variables representing the level of development of the economy, such as the weight of finance in the economic system, the importance of innovation, the quality of the labor force (by proxy with education and health expenditures), or the proportion of the urban population. Combined with the sectoral specialization, it allows us to enrich the different kinds of development. Institutional environment is taken into account by way of variables relative to regulatory requirements (Sambharya and Musteen 2014). We choose to consider only institutional regulatory variables. These variables are particularly interesting for the implementation of public policies because they can be more easily controlled in the short run to promote entrepreneurial activities. In this set of variables, we distinguish the requirements to set up a firm (time, cost, procedures, and barriers), labor market regulations (employment protection, minimum wage, inflows of foreign population), and market openness indicators (foreign direct investment, outward/inward position, net barter terms of trade, trade). In addition, we consider variables specific to the entrepreneurial population: for each class, we identify the relative importance of necessity/opportunity motives (OEAI), the Nascent Entrepreneurial Activity Index (NEAI) and the Young Firm Entrepreneurial Activity Index (YFEAI), ratios obtained through the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), and which are supposed to differ according to the different classes of countries obtained. These variables and their availability periods are described in Table 1.

A break in the dynamics of entrepreneurship: the global financial crisis

To analyze the dynamic of development over the 1999–2012 period, we study the annual average evolution of the variables relative to the economic and entrepreneurial activity—UNEMPL, GDP, SEMPLShare and SEMPLGrowth—for the 26 OECD countries. In this analysis, years play the role of “individuals” and average annual rates the role of variables. A cluster analysis was applied to group the years of the 1999–2012 period into homogeneous classes or sub-periods. More precisely, a hierarchical ascendant classification (HAC) was used on the significant factors of the principal component analysis (PCA) of average annual rates of the four variables of dynamic development. This methodological linking of factorial and clustering methods constitutes an instrument for statistical observation and structural analysis of data. The dendrogram in Fig. 3 represents the hierarchical tree of the years with a characterization of the main results of the chosen partition into three periods.

Clearly, the effect of the crisis is noticeable in 2009 with a rate of GDP growth and a rate of growth in the self-employed share of the workforce significantly lower than those registered on the overall period. “The recent crisis, characterized by tighter credit restrictions, has arguably hampered new start-ups and impeded growth in existing start-ups as well as their ability to survive in tough market conditions” (OECD 2013, p.7). Although the crisis started in 2007, the decline in rates of GDP and self-employed growth is significantly lower than those registered on the overall period only in 2009. Using panel data on the number of new firm registrations in 95 countries to study the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on new firm creation, Klapper and Love (2011) also show that the impact of the crisis was much more pronounced in 2009.

The first period, comprising the years before the crisis, is characterized by high GDP growth; a high level of self-employment and a low unemployment rate. It is a period of growth favorable to entrepreneurship. However, the crisis significantly impacted the dynamics of entrepreneurship: in the sub-period after the crisis, we can observe that the unemployment rate is significantly higher than average for the whole period and the share of self-employment is significantly lower. The financial crisis seems to have broken the dynamics of entrepreneurship. It clearly appears (Fig. 4) that the rate of growth does not recover its initial level after the crisis: it stands at 1.65% over the 2010–2012 period against 2.92% before the crisis. Consequently, the level of unemployment is still increasing in the last period (but with a lower slope). The self-employment share is steadily decreasing during the whole period (Fig. 3) with an acceleration in 2009—see self-employment growth—due to the closure of numerous firms during the crisis.

According to the OECD (2009), it is important to note that SMEs and therefore self-employed workers are generally more vulnerable in times of crisis; this is for several reasons, including that “it is more difficult for them to downsize as they are already small; they are individually less diversified in their economic activities; they have a weaker financial structure (i.e., lower capitalization); they have a lower or no credit rating; they are heavily dependent on credit and they have fewer financing options.” In addition, they are more vulnerable because they often bear the brunt of the difficulties of large companies.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) has described this crisis as a global job crisis. It has resulted in an increase in the unemployment rate as well as the failure of many businesses, leading to a decrease in levels of self-employment over the 2010–2012 period.

When unemployment increases, there is a very short lag before we observe an increase in the setting-up of new firms, i.e., the refugee effect (Abdesselam et al. 2014). In fact, for some people unemployment acts as a trigger factor for entrepreneurial involvement. Being unemployed is one of the displacement factors (breaks in the life of individuals) that can lead to entrepreneurship (Shapero 1975). The lag in the reduction of the unemployment rate due to new-firm start-ups (Schumpeter effect) is greater because new firms usually do not create a lot of jobs at the beginning of their activity. Indeed, jobs can be considered as quasi-fixed costs in countries where labor market regulation is rigid and it is worth waiting until demand becomes sufficiently constant before hiring employees.

Dynamic regional development and typologies of OECD countries

To better understand the dynamics of the development of entrepreneurship over the period and to take into account the effects of the financial crisis, we carried out an analysis over the three sub-periods: before, during, and after the crisis. The approach adopted relies on a combined use of multidimensional evolutive data analyses that take into account the characteristics of the countries in terms of GDP growth, unemployment rates, the number of self-employed as a percentage of the population, and the rate of self-employment growth as well as its evolution over the 1999–2012 period. According to the similarity of these four rates, we can establish a typology of the 26 OECD countries. The usual analyses of annual data do not allow for a global analysis of the countries and their characteristics because these analyses are carried out separately (year by year) and do not take into account the possibility of their having a common structure across time. The total evolution of the countries is thus studied by a multiple factor analysis (MFA) (Escofier and Pages 1985, 1998), based on a weighted analysis of the principal components of all the data.

This analysis is especially designed to study individuals—namely the countries—characterized by a certain number of groups of the same variables measured at each different moment in time. The MFA highlights the common structure of a set of groups of variables observed for the same 26 countries. The first interest this method offers is to carry out a factor analysis in which the influence of the different groups of variables is equilibrated a priori. This balance is necessary because the groups of variables always differ according to the structure of the variables, namely with their interrelationships. It provides representations of countries and variables that can be interpreted according to a usual PCA. A HAC was then used on the significant factors of the MFA in order to characterize the classes of countries relative to the evolution of the four chosen variables.

The pre-crisis financial period: towards more entrepreneurial economies

The dendrogram in Fig. 5 in the Appendix represents the hierarchical tree of the countries obtained using an HAC with the Ward criterionFootnote 7 according to the active variables over the 1999–2008 period. Table 2 in the Appendix summarizes the main results of the characterization of the chosen partition into six classes, obtained from the cut of the hierarchical tree in Fig. 5.

Entrepreneurial economies (class 1): Australia, Austria, Ireland, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Slovenia, and the UK

This class is characterized by an unemployment rate significantly lower than the average of the 26 countries considered and shows a high growth in self-employment at the end of the period. It corresponds to the development model F described in “Economic development.” Barriers to entrepreneurship are significantly lower in 2003 and 2008.Footnote 8 These countries have an institutional environment in terms of the functioning of labor market and the openness of the country being favorable to entrepreneurship. Their development is based on competitiveness and attractiveness of production factors, including labor inflows of foreign populations that are significantly higher than average. This class is also attractive for FDI in 2002 and 2003 and displays a high level of trade during the 1999–2002 period. It shows the willingness to be competitive via the attractiveness of production factors. These results are in line with those of Simón-Moya et al. (2014) showing that business freedom, trade freedom, and labor market freedom are favorable to opportunity entrepreneurship.

Managerial industrial economies (class 2): Italy, Japan, and Portugal

The countries of this class have a high level of self-employment relative to all countries of our sample during almost the whole period—1999 to 2006—and weak GDP growth for the years 1999 and 2002–2006. They illustrate development path E. They are also characterized by an institutional environment relative to the functioning of the labor market that is unfavorable to entrepreneurship, namely a high strictness of employment protection in the whole period; they have rather high levels of employment in industry but a low performance in industry growth, which could denote some problems in maintaining their market share. In these countries, domestic credit provided by the financial sector as a percentage of GDP is significantly higher than average. These results are in line with those of Klapper and Love (2011), who demonstrated that company creation is higher in countries with greater financial sector development, as measured by bank credit ratio to GDP. The level of expenditure on education is rather low. The NEAI is also weak in 2004 and 2006, which denotes an insufficient renewal of entrepreneurs.

Managerial service economies (class 3): Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, and Spain

These countries present high rates of unemployment and a high level of self-employment growth in 2005 and 2006. We can identify the presence of a refugee effect: unemployment leads to new-firm creation and increased self-employment.Footnote 9 These countries also present a typical path of development of type E. These economies are characterized by a rather low proportion of people owning/managing a business that has existed for up to 3.5 years and some institutional restrictions on entrepreneurship. Barriers to entrepreneurship are significantly higher in 1998 and 2003. Clearly, these economies are not conducive to opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.Footnote 10 Yet, during the whole period, they attempt to develop entrepreneurship.Footnote 11

Advanced knowledge and service economies (class 4): Canada, Denmark, Hungary, Norway, Sweden, and the USA

These economies are characterized by a weak self-employment growth compared to the average population over the whole period. They recorded a significantly lower GDP growth rate in 2007, suggesting that they were affected by the crisis earlier. This class is composed of highly developed countries with a high proportion of service sector jobs and a high level of education and health expenditures. Jobs in the agricultural sector are significantly lower than the average for all countries. These countries perfectly illustrate development path D.

Industrialized entrepreneurial economies in developing countries (class 5): Chile and the Czech Republic

These economies are characterized by a high level of self-employment from 2003 to 2008 and a high growth in self-employment in 2002 and 2003: they follow a development path of type C. They are also characterized by an industrial specialization with a high level of added value in industry (as a percentage) for all the periods and jobs in this sector from 2006 to 2008. The evolution of industrial production growth and the terms of trade over the 2004–2008 period are rather better than for all the countries considered. Health expenditure is rather low. The share of the service sector in the added value is also significantly lower in this class over the whole period. The institutional environment relative to the functioning of the labor market also helps to characterize this class, namely the minimum wage appears to be significantly lower than average, while there subsist some barriers to entrepreneurship in 2008.

Non-entrepreneurial economy in transition (class 6): Poland

This class is characterized by both a high level of unemployment and a high level of self-employment during the whole period, as well as a high level of self-employment growth for the years 2000, 2001, and 2008. As already mentioned in “Economic development,” Poland is a perfect example of development model of type B. We label this class on account of its characteristics linked to major institutional environment constraints relative to entrepreneurship: the procedures for entrepreneurship are fairly numerous during the whole period, the cost of becoming an entrepreneur is high in 2008, and finally, the barriers to entrepreneurship are rather high in 1998 and 2008. This result is consistent with those of Aparicio et al. (2016), who highlight that this type of regulation generates entry barriers, discouraging entrepreneurship behavior. These specificities show the occurrence of a refugee effect in Poland for this period—the proportion of people aged 15–64 involved in entrepreneurial activity (TEA) out of opportunity is quite low in 2005.—

The financial crisis: 2009

The dendrogram of Fig. 6 in the Appendix represents the hierarchical tree of the 26 countries according to the active variables for the year 2009.

Table 3 in the Appendix presents the results of the characterization of the chosen partition into four classes for the year 2009. Note that the MFA does not allow us to analyze the evolution of variables at an absolute level but it does allow for a comparison between countries. For example, a low unemployment rate in a class does not mean that the countries in this class have not been impacted by the crisis in terms of employment; it only means that these countries were less severely affected than the average of the countries under study. Parker (2009) points out the effect of falling wages in recessions, which may lower the opportunity costs for starting a business and encourage marginal types of new-firm start-ups (Koellinger and Thurik 2012).

Resilient agricultural countries (class 1): Australia, Chile, New Zealand, and Poland

These countries recorded high GDP growth and a high proportion of self-employment relative to all countries of our sample in 2009. These countries are also characterized by a high sectoral specialization and an institutional environment favorable to entrepreneurship. They exhibit a high contribution of agriculture and industry and a low contribution of services to the added value. They also present a high number of jobs in agriculture, favorable net barter terms of trade, a low strictness of employment, and low expenditure on R&D. So, these agricultural economies are the ones that best withstood the crisis in 2009. The effect of the crisis on Australia was considerably lower than in many other countries, for several reasons: Australia’s economy was buoyed by China’s growing demand for resources and the Australian financial system was markedly more resilient. Notably, Australian banks continued to be profitable and did not require any capital injections from the government. Hill (2012) also highlights other factors that could explain the relatively good performance of the Australian economy during the crisis; these factors include monetary and fiscal policy; structures and legal reform; regulation of financial markets; banking history; and corporate governance. The economy of New Zealand is very closely related to that of Australia, most major banks operating in New Zealand being Australian. In addition, Australia is the largest trading partner of New Zealand. In 2009, Chile and Poland appeared to be protected against the financial crisis. These countries were little affected by the crisis due to their limited role in trade and international finance, among other things (Sholman et al. 2012).

Countries strongly affected by the crisis with a loss in competitiveness (class 2): Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Finland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, Slovenia, and the UK

These countries were more affected by the crisis and fell deeply into recession; the GDP growth rate is significantly lower than the sample’s average. However, it seems that the crisis did not stop the dynamics of entrepreneurship; for we see that in 2009, the level of self-employment is above average and the rate of unemployment is significantly lower. Probably, a percentage of those people laid off set up their own firms and are characteristic of push entrepreneurs. These countries also present unfavorable net barter terms of trade. These are economies with a loss of competitiveness in 2009.

Countries mainly coming from the class of advanced knowledge and service economies earlier affected by the crisis (class 3): Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, and the USA

These countries are characterized by a rather low level of self-employment. One possible explanation for the low level of self-employment could be the closure of numerous firms, although, due to the mix of structural and situational effects, it is difficult to assess whether the low level of self-employment has only a cyclical component. Furthermore, we showed that countries belonging to the class of advanced knowledge and service economies were affected by the crisis earlier. The weak level of GDP growth in 2007 might have led (with some delay) to a decline in the level of self-employment. We note that although the cost of business start-up procedures is significantly lower than average, this did not make it possible to boost entrepreneurship during the crisis period.

Countries hardest hit by the financial crisis (class 4): Ireland and Spain

These countries, Ireland and Spain, combine high unemployment rates and a low level of growth in self-employment. In these countries, unemployment rose significantly from 2008 onwards, as a result of a sharp fall in house building leading to major job losses. Construction is among the worst-affected sectors in these countries, where there had been a large boom in residential construction in response to sharply rising housing prices. The crisis reversed the trend of increasing new-company creation.

The 2010–2012 period: a sharp slowdown in entrepreneurial activity

The crisis persisted after 2009, with widespread consequences for economic performance, labor productivity, and employment in all countries around the world. Hysteresis effects are indeed likely to push up structural unemployment as workers who remain unemployed for a long period become less attractive to employers as a result of declining human capital, or as they reduce the intensity of their job search. In 2012, the OECD identified 48 million unemployed people in the OECD countries, about 15 million more than at the beginning of the crisis in 2007. As we underlined in “A break in the dynamics of entrepreneurship: the global financial crisis,” the sub-period after the crisis (2010–2012) is characterized by an unemployment rate significantly higher than the average over the whole period and a level of self-employment significantly lower.

The dendrogram in Fig. 7 in the Appendix represents the hierarchical tree of the countries according to the active variables over the period 2010 to 2012. Table 4 in the Appendix presents the results of the characterization of the chosen partition into five classes of countries for the post-crisis period. So, now let us look at what has happened since the crisis. The aim of the analysis over this period is to study the dynamics of entrepreneurship after the crisis and identify whether recovery processes are under way in some countries which are more or less resilient to the crisis and in which entrepreneurial behaviors remain dynamic.

Advanced knowledge and service economies with developed financial markets deeply affected by the crisis (class 1): Australia, Canada, Denmark, Japan, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, and the USA

This class shows a significantly low level of self-employment relative to all countries of our sample over the 2010–2012 period. This shows that the dynamics of entrepreneurship was deeply affected by the crisis. However, these countries recorded an unemployment rate lower than average, which could be a sign of recovery. This is confirmed by data on the evolution of growth rates that show higher than average growth rates for high-income countries for the year 2013 except for Denmark and Norway (World Bank 2014). For Canada and the USA, a probable explanation is their higher sensibility to cycles, with not only a hugely depressed level in the recession phase but also a quick and strong recovery in the growth phase (Aghion 2014). Yet, it is also recognized that the recent recovery in the USA did not proceed very fast (Dwyer and Lothian 2011). According to Solomon (2014), financial crises cause permanent damage that lead to huge losses in output levels from initial trends. In addition, Siemer (2014) shows for the USA that the number of firms less than 1 year old—which we can identify as business start-ups-declined by more than 25% in 2007–2010, leading to a “missing generation” of new firms. The class includes highly developed countries with high sectoral specialization, belonging to advanced knowledge and service economies. We observe that although the functioning of the labor market is favorable to entrepreneurship, namely with the attractiveness of production factors and low employment protection, these countries have a level of self-employment that is significantly lower than the average employment level of the population.Footnote 12 The OECD (2013) underlines that in Australia, Japan, and the USA, “self-employment levels remain significantly below their pre-crisis level, reflecting in part a shift towards contractual employment, where employment levels were less adversely affected by the crisis.” This situation can be explained by the evolution towards more qualitative entrepreneurship leading to a structural decrease in the self-employment share. In general, these countries show a high level of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, and this is the case for 2010 and 2011. These results are in line with recent reports by GEM (2016–2017, 2014, 2015–2016, 2013, 2011). Moreover, these countries are also characterized by a significantly high level of domestic credit provided by the financial sector as a percentage of GDP.

Credit crunch impact on domestic activity and push entrepreneurship in relatively industrialized countries (class 2): Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Slovenia, and the UK

The characteristics of this class relative to the unemployment rate and GDP growth rate are similar to those of the sample’s mean. These countries registered a significantly high level of self-employment over the period and a high rate of growth in this level in 2012. Probably, part of the people laid off set up their firms and became self-employed to earn a living. In these countries, employment in industry is significantly higher than the average over the 2010–2012 period. We also notice that the share of domestic credit provided by the financial sector as a percentage of GDP is lower than the average in 2010 and 2011.

Countries pursuing a dynamic entrepreneurial development (class 3): Chile and Mexico

It is clear that the South American countries are the countries least affected by the crisis: they show significantly higher levels of GDP growth with higher levels of self-employment over the period. They also feature a high number of people currently setting up a business, as well as a significant number of people owning or managing a business that has existed for up to 3.5 years. These characteristics reflect a dynamic form of entrepreneurship. The industry and agriculture sectors contribute significantly to the value added, while the service sector is under-represented. Institutional environment features, especially net barter terms of trade and lower minimum wages, are more favorable to entrepreneurship in these countries over the period. Globally, this class consists of countries with an economic performance superior to that of the average of the entire sample. These countries are developing countries with health expenditures significantly below the average of OECD countries. The share of domestic credit provided by the financial sector as a percentage of GDP is lower than the average in 2010 and 2011. In these countries, where financial markets are less developed and play a limited role in the national economy, the financial crisis did not severely affect the dynamics of entrepreneurship. The global financial crisis had a relatively limited impact on Latin American economies. The financial systems of these countries did not suffer a ripple effect because they are not very sophisticated and globally less integrated.

Volatile self-employment growth in an uncertain environment (class 4): Hungary

Hungary registered variations in the level of self-employment growth with a rather high growth in 2011 but a low one in 2012. We could thus infer for this country a kind of volatility in self-employment as a means of adjustment. Real GDP has remained broadly flat over the recent period due to weak domestic demand moderated by net exports which remain the only source of growth. Investment in the country has reached its lowest level in 10 years. Hungary’s public sector is highly dependent on foreign financing: almost two-thirds of Hungary’s public sector debt, which stands at about 80% of GDP, is held by foreigners. Growth prospects are largely unfavorable due to the low real wage growth, rising debt servicing, unemployment, and a credit crunch. Importantly, confidence has suffered in a policy environment that is perceived by many investors and consumers as unpredictable and discriminatory. Hungary was initially considered as the front-runner of market reforms in Central and Eastern Europe, but by the end of the 2000s, its economy was facing major structural problems: “It seems that in Hungary, in spite of its head-start as the most entrepreneurial country amongst the socialist countries in 1970s and 1980s, lags in its cultural attitudes and lack of political recognition of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs” (Szerb et al. 2013, p. 47).

Countries greatly impacted by crisis, entrepreneurship slowdown (class 5): Ireland, Portugal, and Spain

Here, the unemployment rate is significantly higher and the rate of growth significantly lower than the average of the entire sample over the period. The rate of self-employment growth is also significantly lower than the average in 2010 and 2011. This class includes sparsely urbanized countries with high levels of domestic credit provided by the financial sector as a percentage of GDP. In these countries, new firms are strongly dependent on bank financing. The individual situations of these three countries are somewhat different. In Spain, the ailing banking sector had lent heavily to the construction sector before the housing bubble burst. In Ireland, the property bubble was funded by banks which went bust and were taken over by the state, causing a government debt crisis. Portugal suffers from moderately high indebtedness of the private and public sectors, low competitiveness, and anemic growth. The crisis has severely impacted the countries of this class, leading to many bankruptcies and a slowdown in entrepreneurship dynamics in 2010 and 2011. The proportion of people aged 15–64 involved in entrepreneurial activity (TEA) out of opportunity is quite low in 2010 and 2011.

Our results point out that classes 2 and 3, which have been the most resilient to the crisis in terms of self-employment—both in share and growth—are characterized by a low level of domestic credit provided by the financial sector, whereas countries of classes 1 and 5 which are strongly dependent on bank loans have recorded lower-than-average self-employment growth and share. These findings are corroborated by Klapper and Love (2011), who observe that “One feature of the crisis was its severe impact on the functioning of financial markets, which resulted in a credit crunch and credit rationing. It is not surprising that countries in which financial markets played a larger role in the domestic economy would experience sharper contractions in new firm creation during the crisis.” Nevertheless, the advanced knowledge economies with developed financial markets, fewer regulatory institutional constraints, and greater scope for qualitative entrepreneurship, i.e., class 1 has lower unemployment rates.

Trajectories of the 26 OECD countries over the period

The methods of joint analysis of several data tables—evolutive data—also make it possible to study and represent the evolution of the trajectories of countries to explain the similarities and differences between active variables between sub-periods. If we follow the trajectories of the 26 OECD countries (Table 5 in the Appendix), we can see that some countries are still grouped together regardless of the sub-period. That is the case for Canada, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and the USA. These countries were classified in the class of advanced knowledge and service economies and show a more opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. Aghion (2014) underlines the fact that innovation implies creative destruction and that some countries are more able to surf on the new waves of innovation. According to him, the USA, Sweden, and Canada are more likely to benefit from technologies such as ICT or renewable energies due to reforms in the labor market to make it more dynamic, the concentration of resources on the knowledge economy, support of new innovative firms, support for salaried people who leave their jobs, and increased competition in the market of goods and services.Footnote 13

Slovenia, Austria, the Netherlands, and the UK follow the same pattern throughout the period—belonging to the set of entrepreneurial economies, they have been severely impacted by the crisis due to their loss of competiveness—and they suffer in the third period of credit crunch and entrepreneurship mainly due to push motives. These countries showed a rather high level of immigration during the pre-crisis period and were oriented towards exports and attracting foreign investments.

Belgium and Finland, which come from the managerial services economies, follow the same trajectory as the four previous countries.

While France and Germany are often seen as “brother enemies” at the European scale due to their policies—with the German country leader of the northern part more inclined to a strict obedience regarding debt, and the French leader of the southern part less concerned with severe control of debt—they both belong to the set of managerial economies with rather less opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, and finally follow the same trajectory. Coming from the class of managerial services economies, they were less affected by the crisis in 2009,Footnote 14 but they also suffer in the third period from the credit crunch.

Conclusion

The present paper aims at proposing a classification of OECD entrepreneurship relative to GDP growth, unemployment rates, self-employment levels, and the rate of growth in self-employment, using a database covering the 1999–2012 period. In order to characterize classes and the different kinds of development focusing on entrepreneurial activity (managerial/entrepreneurial), we consider variables representative of economic development and the institutional regulatory environment. A multivariate and evolutive data analysis is thus implemented. The results underline the great impact of the financial crisis on entrepreneurial dynamics and lead us to distinguish three sub-periods to study entrepreneurial behavior: the pre-crisis period (1999–2008), the crisis (2009), and the post-crisis period (2010–2012). The first period is characterized by high GDP growth, high levels of self-employment, and a low unemployment rate. It is a period of growth favorable to entrepreneurship. The effects of the financial crisis are noticeable after a delay in 2009; this year is characterized by a rate of GDP growth and a rate of self-employment growth significantly lower than those registered on the overall period. The 2010–2012 period shows a sharp slowdown in entrepreneurial activity; the crisis seems to have significantly broken the dynamics of entrepreneurship. We can observe in the sub-period after the crisis that the unemployment rate is significantly higher than the average of the whole period and the level of self-employment is significantly lower.

Based on the pre-crisis period, we identified six types of development: entrepreneurial economies, managerial industrialized economies, managerial service economies, advanced knowledge and service economies, industrialized entrepreneurial economies in developing countries, and a non-entrepreneurial economy in transition. Managerial economies are characterized by high strictness of employment protection and some restrictions to entrepreneurship, such as time and number of procedures required to start a business, as well as barriers to entrepreneurship, that also lead to a low level of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial economies are characterized by strong competitiveness and attractiveness of factors of production in highly developed countries, while they exhibit low actual wages in developing countries. We find that, regardless of the type of development, this period is characterized by strong entrepreneurial activity. This result corroborates those of Klapper and Love (2011) who observed a steady increase in new business registrations prior to the crisis in all groups of countries.

In 2009, it appears that the agricultural economies (Australia, Chile, New Zealand, and Poland) best withstood the financial crisis. The analysis of the post-crisis period (2010–2012) shows that the development of entrepreneurship has been severely impacted by the crisis in countries more dependent on the financial sector: such is the case for Ireland, Portugal, and Spain and to a lesser extent Australia, Canada, Denmark, Japan, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, and the USA. However, it appears that entrepreneurship is particularly dynamic over the 2010–2012 period in countries where the level of domestic credit provided by the financial sector as a percentage of GDP is lower (classes 2 and 3). Nevertheless, class 1—made up of advanced knowledge economies with developed financial markets, fewer regulatory institutional constraints, and more scope for qualitative entrepreneurship—has a lower unemployment rate.