Abstract

While others have examined the implementation and/or the stringency of enforcement of antitrust laws in post-socialist economies, this paper is the first study that attempts to explain the patterns of antitrust enforcement activity across post-socialist countries using economic and political variables. Using a panel of ten European post-socialist countries over periods ranging from 4 to 11 years, we find a number of significant factors associated with enforcement in these countries. For example, our results suggest that countries characterized by more unionization and less corruption tend to engage in greater antitrust enforcement of all types. Countries more successful in privatizing have filed fewer cases, while more affluent or developed countries investigate fewer cases of all types, consistent with an income-shifting motivation for antitrust. In general, countries have tended to increase their enforcement efforts over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There is a large literature exploring determinants of antitrust enforcement in the United States, the vast majority of these based on aggregate federal enforcement data over time (exploring cyclical influences) or cross-industry studies, usually for a single year or aggregated over several years. Less well-explored is the explanation of European antitrust (or competition) policy; no systematic econometric investigation of patterns of enforcement in the new antitrust regimes of Central and Eastern Europe has been undertaken.

Soon after the transition in Central and Eastern Europe from central planning to democratic, market-oriented nations, there was no shortage of suggestions by American economists as to how these countries should structure their institutions aimed at establishing and maintaining competitive markets.Footnote 1 At this point, 15 years since most have created antitrust or competition authorities, it is worth looking back and exploring the economic and political determinants of the enforcement which emerged. In what follows, we explain antitrust enforcement across ten European post-socialistFootnote 2 countries and varying numbers of years (on average, seven) between the mid-1990s and 2007 (or earlier for countries which have joined the EU). The countries have been chosen in part due to availability of data, but reflect the major economies of the region.Footnote 3 A pure public interest perspective predicts antitrust activity as a response to monopoly and cartel welfare losses, while more modern economic theories of regulation focus on political variables and the extent to which cyclical patterns influence enforcement activity through their impact on the interests of affected parties. We consider a variety of political and economic rationales in the analysis below.

2 Previous Literature on Determinants of Antitrust Enforcement

Note that we do not discuss here the large literature, both for the U.S. and Europe, on the deterrent impact of antitrust enforcement on company behavior.

As discussed in Ghosal and Gallo (2001), there are two commonly cited justifications for antitrust enforcement. First, antitrust laws may be used to correct for deviations from competitive behavior; these corrections increase consumer welfare at the expense of producers, with potential gains in welfare to society. Second, interest groups may lobby for antitrust enforcement to redistribute wealth from one group (producers) to another (consumers or other—perhaps less efficient—producers); in this case, the net impact on society is more likely to be negative.

Besanko and Spulber (1989) and Harrington (2004) have provided theoretical models of optimal enforcement, with the former focusing on enforcement costs and the need to “tolerate” some cartel activity given asymmetric information on production costs, and the latter noting that antitrust enforcement/detection will likely be a function of price changes (suggesting some perverse incentives enforcement provides to cartels). Previous empirical literature has explored the determinants of antitrust enforcement for the U.S. at the federal level, either over time or across industries (generally not both). For example, Long et al. (1973) examined 20 2-digit SIC industries and found industry sales to be the most important economic factor explaining antitrust filings, with a lesser influence of measures capturing actual or potential monopoly power (such as profit margins, seller concentration, and estimated deadweight losses).

Siegfried (1975) disaggregated the analysis a bit to 65 IRS “minor industries” and concluded that economic variables generally seem to have little influence on Antitrust Division enforcement activity; while an estimate of welfare loss (in some specifications) did have a positive impact on case filing activity, this disappeared when differing sizes of industries (measured by numbers of firms) were controlled for. Market concentration (in some specifications) had the expected positive impact on antitrust cases, but even here the economic variables had a very low level of explanatory power, and generally speaking, results were quite sensitive to specification and measurement issues.Footnote 5 Both Masson and Reynolds (1977) and Pittman (1992b) point out flaws in these studies, both in statistical analysis/data measurement and in interpretation. In particular, appropriate economic market definitions are far narrower than what is incorporated in the previous econometric work, cases brought by the US Federal Trade Commission (which shares antitrust enforcement responsibility with the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division) are excluded, and both deadweight losses and economic profits are likely measured in error. Perhaps most importantly, a rational antitrust enforcer might pursue cases with a smaller static welfare loss so as to reduce the costs of victory and to provide deterrence and precedent value in the future.

Ghosal and Gallo (2001) performed a time series analysis over 40 years of annual data and found that antitrust enforcement by the U.S. Department of Justice is countercyclical. The authors speculate that this is because antitrust violations increase during periods of declining economic activity (as firms are more desperate to maintain profit levels).

All studies note that political motivations obviously may play a role in enforcement (this is emphasized by Wood and Anderson (1993)). Empirical studies of the national level of antitrust enforcement such as Areeda (1994) and Ghosal and Gallo (2001) have investigated whether antitrust enforcement increases under Democratic administrations, with mixed results.Footnote 6 Feinberg and Reynolds (2010) examine variation across U.S. states in antitrust enforcement over the 1992–2006 period, finding both economic and political determinants to play a role—- case filings tend to be countercyclical, influenced by the political party of the state’s attorney general, and positively related to a state’s economic size and relative size of the government in the economy.

For Europe, Gual and Mas (2008) investigate the determinants of European Commission decisions (rather than, as considered here case filings/investigations) with some support given for the role of economic vs. political factors. Carree et al. (2010) also provide an analysis, largely descriptive, of European Union antitrust enforcement and its patterns over time—with some results hinting at the lack of political bias or non-EU-member bias; they also provide a brief discussion of the limited prior literature explaining European merger control (e.g., Duso et al. (2007)) and individual member country antitrust enforcement. Of the latter, Davies et al. (1999) find that market shares predict well UK antimonopoly enforcement success, and Lauk (2003) obtains similar results for German antitrust enforcement.

The patterns of European post-socialist antitrust enforcement have been less-studied, though Pittman (2004) examined some data on antimonopoly enforcement in those countries and Holscher and Stephan (2004)—focusing on early EU-candidate nations in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE)—provide some descriptive discussion of national antitrust/competition laws and enforcement. Others have examined the related issue of patterns of implementation of competition laws in transition economies; these include Fingleton et al. (1996) and Dutz and Vagliasindi (2000).Footnote 7 No systematic econometric investigation has been undertaken, however, of factors explaining activity by anti-trust authorities in Central and Eastern Europe.

3 Antitrust Institutions in Central and Eastern Europe

Countries emerged from socialism with production structures characterized by very large firms, designed to fully serve specific local or national markets. These firms were also highly vertically integrated (Feinberg and Meurs 1994). Early post-socialist reforms thus typically included anti-monopoly legislation. Poland introduced the initial anti-monopoly legislation during the economic crisis that preceded the collapse of socialism (1987), while most other countries in this study implemented legislation soon after the collapse, between 1990 and 1992 (Dutz and Vagliasindi 2000).Footnote 8 The early laws were modeled closely on EU competition policy,Footnote 9 especially Articles 85 and 86 of the Treaty of Rome (Pittman 1998).Footnote 10 Still, the early legislation suffered from some significant weaknesses, particularly the lack of a clear distinction between horizontal and vertical agreements and a lack of guidance regarding how to define relevant markets and, relatedly, an overly simple approach to defining market dominance (Pittman 1998; Boner and Kovacic 1997–1998). EU accession countries implemented amendments as part of the accession agreements, bringing their policy more closely into line with EU competition law. These amendments to a large extent reduced the weaknesses outlined in Pittman (1998). All countries in our sample except Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia and Ukraine, became EU members in 2004 and implemented the amendments to competition policy in the mid- to late-1990s, during accession negotiations. Bulgaria and Romania joined in 2007; Bulgaria amended competition policy in 1998, whereas Romania, which adopted its initial legislation only in 1996, was not required to implement reforms prior to integration.

Croatia and Ukraine have not yet joined the EU, and may thus have policy less closely aligned with Western standards. Ukraine made important amendments to its early competition policy in 1994, drawing heavily on Western and EU anti-trust law, but the amended legislation left many issues more broadly or simply defined than comparable EU legislation. Boner and Kovacic’s (1997–1998) analysis of Ukraine’s competition policy in 1997 found that Ukraine continued to rely heavily on simple (“per se”) measures of market power, which seemed to contribute to high levels of anti-trust activity. The authors argue that a weak judicial system leaves anti-trust cases open to political manipulation, as courts have not effectively reviewed outcomes. Further potential for politicization of anti-trust policy derives from the significant role the state and ministries continue to play in owning and influencing enterprises in Ukraine (Stotyka 2006). The state may thus face conflicting motives with respect to monitoring the behavior of these enterprises. Further amendments in 2002 allowed for more consideration of the degree of competition in markets (beyond simple market share), but possibly increased political manipulation of anti-trust actions, giving Ministries the ability to over-ride competition agency decisions related to firms under their control (Stotyka 2006).

In the countries under consideration here, most major legislation was in place by 2000. The EBRD Competition Policy Indicator suggests little change in policy or enforcement over the period 2000–2007. On a scale from 1 to 4+, no country in our sample raised its score by more than one-third of a point (from 2+ to 3−, for example) over this period (EBRD Transition Reports 2000–2008, cited in Holscher and Stephan 2004).

However, Holscher and Stephan (2009) argue that despite the early establishment of competition laws, these laws did not really begin to be enforced until around 2006. Holscher and Stephan (2004) also found that despite the common basis in EU policy, there continue to exist significant legislative differences among EU accession states (2004). Enforcement capacity varies significantly between countries, depending on the financial resources and skills at their disposal. Agency staff varies from 11 people in Slovenia to 346 people in Romania. Budget per staff member also varies significantly, from $4,777 in Romania to $38,962 in Slovenia. As a share of the national budget, Slovakia spends the least, while Lithuania spends twice as much (Nicholson 2008). An additional issue is whether antimonopoly agencies are independent and able to enforce laws independently of political pressures.

Competition agencies in Central and Eastern European countries, which implement the laws, differ in their focus, and more importantly, in their level of independence.Footnote 11 With the exception of Poland, competition agencies in all countries examined here see their job as creating and protecting competitive markets. The Polish Competition Authority focuses more directly on end results of market structure--protecting consumer interests. A related difference is in specific standards used to establish anti-competitive behavior. Hungary, for example, recently moved from a dominance test for mergers to a test of “significant lessening of competition”. Some country competition authorities focus attention on issues like price gauging (Romania), but without applying any standard, usual, criteria for determining the presence of such practices. Others stick more closely to an EU-type emphasis on exclusionary behavior (Hungary).

Heads of competition offices are, in general, appointed by the country president.Footnote 12 In some cases, including the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Lithuania, they are appointed for a fixed period, often exceeding the term of the President, offering them a greater degree of independence. In other countries, including the Slovak Republic and Ukraine, the heads and other high-level staff of competition agencies appear to serve at the will of the President.Footnote 13

There have been a number of attempts to evaluate and compare the overall comprehensiveness and effectiveness of these anti-trust policies. Results of the main studies are presented in Table 1. These studies suggest that significant variation exists between countries in the level of regulation and enforcement of anti-trust issues, but they do not produce a consistent ranking of anti-trust policy, nor do they seek to explain these differences as we attempt in what follows.

Columns 1 and 2 of Table 1 present the results from a survey conducted by the World Economic Forum of business leaders in 2001, which asked them to rank anti-trust policy between lax (1) and effectively promoting competition (7). Hungary and Poland rank at the top of this measure, but Lithuania joins Ukraine at the bottom (Holscher and Stephan 2009). Bulgaria and Croatia were not ranked in this survey.

Two other measures of antitrust activity are based on EBRD data. A survey done in 1999 based on data from 1996–1997 and measuring enforcement and advocacy (not legislation itself), finds Poland, Hungary and Lithuania to have the most effective anti-trust implementation, and Ukraine and Croatia to have the weakest (Dutz and Vagliasindi 2000).

The EBRD Competition Policy Indicator, which measures both legislation and enforcement (Holscher and Stephan 2009; EBRD 2004), covers all years included in our survey (1995–2008). On average for the whole period, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia are at the top. Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Ukraine are at the bottom.

Finally, Hylton and Deng (2006) examine competition laws in 102 countries, looking specifically at the categories of Territorial Scope, Remedies, Private Enforcement, Merger Notification, Merger Assessment, Dominance and Restrictive Trade Practices for the period January 2001-December 2004. Scores range from 25 (Australia, with the most comprehensive legal basis for anti-trust legislation) to 2 (Paraguay, with apparently almost no legal basis for such legislation). As can be seen from Table 1, the former socialist countries in our sample are significantly bunched around 20. Hungary is found to have the most comprehensive legislation, earning a 24, while Bulgaria has the least comprehensive, earning a 17. Ukraine, which does not rank near the top of other anti-trust policy rankings, is found to have very comprehensive legislation, ranking second.

We take a slightly different approach here, examining factors underlying the patterns of antitrust case filings in the individual countries. Eight of the ten countries we study have by now joined the European Union, which means their antitrust enforcement (at the country level) is now somewhat more akin to that of individual states in the US. For this reason we include only data points through the year prior to EU accession; motivations for filing cases, and the nature of cases pursued, will be different when a central authority is available to deal with anti-competitive actions by companies active in multiple jurisdictions.Footnote 14 As a result, our sample period ends in 2003 for the Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia; in 2006 for Bulgaria and Romania; and in 2007 for Croatia and Ukraine (not due to accession, rather simply for data availability reasons). The start date for observations varies and depends on availability of competition/antitrust case information. Antitrust case information was obtained from competition agency websites, including the annual reports provided there, as well as additional enforcement data provided by staff at some of the agencies.Footnote 15 In total our analysis is based on 71 data points. Table 2 reports the sample sizes by country.

The case data are broken down into (1) abuse of dominance (or monopolization) cases; (2) prohibited agreements (mostly cartel-type, price-fixing agreements); and (3) concentrations (or merger) investigations, as well as the total of these; we expect these categories correspond well to the comparable categories dealt with by the US and EU enforcement agencies. The latter of these categories often reflects total merger activity in the country rather than a choice by the agency towards enforcement, and it will be of interest to see if determinants of this type of enforcement activity differ from those of the first two (generally more discretionary) categories.

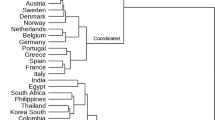

Figs. 1 and 2 illustrate the differences in total antitrust enforcement activity by country and over time. The average number of antitrust cases varies significantly across the countries in our sample, ranging from 58 per year in Slovenia to 948 in the Ukraine and 1,230 in Poland.Footnote 16 These summary statistics do not seem to reflect the results from many of the studies described in Section III. For example, the 1999 EBRD survey which measured antitrust enforcement activity ranked Poland as having some of the most effective antitrust legislation, but the Ukraine as having some of the weakest (though, as noted by Hylton and Deng (2006), Ukraine’s laws are among the most comprehensive in coverage). Part of this discrepancy could be explained by the various sample periods of the surveys described in Section III and the significant variation in antitrust enforcement over our sample period, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Poland, for example, experienced a 150% decrease in total antitrust enforcement activity between 1998 and 2003. In contrast, the Ukraine experienced an increase of 54% between 2003 and 2007. Of course, it must be kept in mind that case activity does not necessarily imply effectiveness (and we discuss this issue below).

Table 4 breaks down the antitrust activity of the countries in our sample more closely, reporting the average number of abuse of dominance, prohibited agreement and merger cases filed by each country over the sample period. There are some notable differences. For example, officials in Lithuania and Slovenia spend relatively more of their antitrust enforcement resources on merger activities; on average, half of all of the antitrust enforcement in our sample is comprised of merger cases compared to 76% of Lithuania’s enforcement and 84% of Slovenia’s enforcement. Similarly, the Czech Republic, Romania and the Ukraine spend relatively more of their antitrust enforcement resources on prohibited agreement cases when compared to the other countries in our sample.

4 Data and Econometric Specification

As suggested by the literature discussed above, we hypothesize that the level of antitrust activity in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe is a result of a number of local political and economic influences. To investigate this hypothesis, we estimate to what degree a wide variety of political and economic variables explain the intensity of antitrust enforcement, or the variation in the number of antitrust cases initiated by the countries in our sample relative to their economic size; the dependent variable in our regressions is the number of antitrust enforcement cases divided by the country’s Gross Domestic Product in billions of 2,000 dollars. In addition to conducting our analysis on all antitrust activity conducted by the countries in our sample, we separately analyze three separate categories of antitrust cases: those targeting (1) abuse of dominance (or monopolization) cases; (2) prohibited agreements (mostly cartel-type, price-fixing agreements); and (3) concentrations (or merger) investigations.

We acknowledge that the observed level of antitrust enforcement in each country is the product both of government efforts to pursue violators and the true amount of anticompetitive behavior in each country. Imagine that the amount of anticompetitive behavior is identical in each country. In this case, our dependent variable is an excellent measure of the degree to which countries choose to pursue these anticompetitive violations based on local political and economic conditions. In contrast, if all anticompetitive violations that occur in the country are pursued, then our dependent variable measures only the amount of the anticompetitive behavior existing.

In order to disentangle these competing explanations for cross-country variation in antitrust activity, we control for the likely amount of anticompetitive behavior in each country by including variables that we believe are significant determinants of such behavior. In other words, our estimating equation for cases filed is best seen as a reduced-form of two equations: one that explains the frequency of violations (given firms’ assessment of the gains and costs from anticompetitive behavior), and the second that explains the antitrust enforcer’s decision on which cases to pursue, given violations.

As a hypothetical example, suppose that countries allocate more resources to antitrust enforcement during periods of recession, which would increase the probability that they will launch a successful prosecution of anticompetitive actions which are occurring. Although the recession may make it more profitable for firms to engage in anticompetitive behavior, the increase in the probability of enforcement would reduce the expected benefits from the behavior; the total impact of the variable on the number of anticompetitive actions and, thus, number of cases brought is unclear.

In this analysis, we include a wide variety of explanatory variables that reflect the potential economic and political influences on the intensity of enforcement; these variables are discussed more fully below. Although many of these variables may influence both the number of antitrust violations and the level of antitrust enforcement in the country, we have some a priori beliefs that certain variables will have a greater effect on the number of violations than on the number of the violations that are prosecuted, and vice versa.

4.1 Determinants of the Level of Anticompetitive Behavior in a Country

As discussed above, Ghosal and Gallo (2001) found that the level of antitrust activity in the United States is countercyclical. The authors speculate that this relationship is driven by the fact that antitrust violations increase during periods of declining economic activity because firms are more desperate to maintain profit levels. To control for this possibility, we include the country’s annual GDP growth rate from World Development Indicators.Footnote 17

Countries in which a high proportion of enterprises are controlled by the public sector would seem to have little need or motivation to engage in anticompetitive activities.Footnote 18 To account for variation in the degree of transition in the CEE countries in our sample, we include the Large Scale Privatization Index compiled by the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). This index ranges from 0 to 4.Footnote 19

In specifications using time-invariant variables, we include a measure of the degree of market competition in the economy, speculating that less competitive markets are likely characterized by more anticompetitive activity. Specifically, the variable Share with <=3 Competitors is the share of firms reporting that they had 3 or fewer competitors from the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey. The World Bank and EBRD conducted this survey of over 4,000 firms in 22 transition countries in 1999–2000.

4.2 Determinants of the Proclivity of the Country for Antitrust Enforcement

One theory of antitrust enforcement speculates that enforcement may be a method of allowing government agencies to redistribute wealth from producers to consumers. If this is the case, one might expect antitrust enforcement to decrease as the country becomes more developed and feels less of a need to redistribute wealth to its low income consumers; we include the country’s GNI per Capita to account for this possibility.

To account for the possibility that unions may enact pressure on officials to secure antitrust enforcement on particular firms, we include estimates of union membership rates (Estimated Unionization Rate); it is also possible, however, that unions may share monopoly rents with large employers and support them in opposing antitrust activity, so the expected sign of this variable is somewhat ambiguous. For the Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia, this variable was taken from unpublished estimates by Lucio Baccaro based on survey data collected by Jelle Visser..Footnote 20 In the case of Bulgaria and Romania, we use International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates published in their World Labour Report 1997–1998 for a period around 1995 and extrapolate the later years based on the time trend patterns observed for the 6 countries included in the Baccaro estimates. We estimate the unionization rate in Croatia and the Ukraine in a similar manner using recent membership data from the Federation of European Employers (and labor force figures from the CIA World Factbook), and then extrapolating backwards using the same time trend pattern.

Two of the components of the Economic Freedom Index compiled by the Heritage Foundation may explain some of the variation in antitrust activity across CEE countries. Countries with larger governments may engage in more antitrust enforcement for a number of reasons. First, such states may have more financial resources available with which to pursue antitrust matters. States with larger governments may also tend to be more interventionist in general. We include a measure of the size of the government role in the economy, the Government Spending Index, from the Heritage Foundation. This index ranges between 0 and 100, and measures the level of government expenditures as a percentage of GDP. Footnote 21

The second component, the Freedom from Corruption Index measures the perceived level of public sector corruption in the country. The Heritage Foundation derives its Freedom from Corruption Index from Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). The CPI is based on a 10 point scale in which a score of 10 indicates little corruption; the Freedom from Corruption Index multiplies the CPI by 10, thus the Freedom from Corruption Index ranges from 0 to 100. It is not immediately apparent what impact public sector corruption would have on antitrust enforcement. On one hand, corrupt government officials may pursue more antitrust cases in order to secure payoffs from firms. On the other hand, firms may be able to pay off government officials in corrupt governments to avoid antitrust action.

Finally, we include (to control for differing experience with antitrust) the time since first adoption of antitrust laws (Years Since Adoption), from Dutz and Vagliasindi (2000). Of course, causal claims from our results need to be tempered by the lack of a formal structural model being estimated; nevertheless our findings of empirical regularities associated with the patterns of CEE antitrust enforcement remain of interest.

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics on both the antitrust case data and the explanatory variables.

We estimate our model using a fixed effects panel regression model. As in most panel data of this nature, it is important to control for potential unobserved heterogeneity across countries. In other words, there are likely to be unobserved characteristics associated with each country that impact the level of enforcement over all years in the sample, including differences in enforcement systems and the focus of competition authorities. This unobserved heterogeneity can be modeled as either a fixed effect or a random variable that follows some known distribution. Although random effects can be more efficient in some cases, if the unobserved component is correlated with the explanatory variables, use of the random effects model will result in biased coefficient estimates. Hausman tests suggest in this case that random effects are inappropriate.

Unfortunately, inclusion of fixed effects in panel regressions prevents the estimation of time-invariant variables—those country-specific variables that do not vary over time. It also makes it difficult to identify the impact of those variables that do not vary much over time. Therefore, in other specifications we estimate our model using the fixed effects vector decomposition estimator developed in Plumper and Troeger (2007). While details and the statistical properties of the estimator can be found there, intuitively, parameters of the model are estimated in three stages. The first stage estimates a pure fixed effects model. The second stage decomposes the fixed effects vector into a part explained by the time-invariant (or almost time-invariant) variables and an error term. Finally, the third stage re-estimates the original model by pooled OLS, but includes the time-invariant variables and the error term of the second stage in place of the fixed effects. The estimator allows for the inclusion of time-invariant and nearly time-invariant parameters.

5 Results

Results from the estimation of the fixed effects panel regression model are included in Table 5. As noted in the previous section, the dependent variable in these regressions is the log of the number of antitrust enforcement cases divided by the country’s Gross Domestic Product in billions of 2000 dollars; in other words, the dependent variable measures the intensity of antitrust enforcement relative to the economic size of the country. All variables were logged prior to estimation, thus the estimates represent elasticities.

Column 1 of Table 4 presents the impact of the explanatory variables on the relative intensity of all antitrust enforcement conducted in a specific country in a given year. Of those variables proposed in Section IV, four prove to be statistically significant. First, countries appear to be more likely to engage in antitrust enforcement activity the higher the unionization rate in the country, suggesting that unions may be able to put pressure on governments to take actions against specific firms. Specifically, a 1% increase in the level of unionization increases the relative intensity of antitrust enforcement activity by 1.4% in a given year. The results also suggest that countries engage in relatively more antitrust actions the less corrupt their public sector. The parameter estimates indicate that a 1% increase in the Freedom from Corruption index increases enforcement activity by 1.8%, perhaps suggesting that corrupt officials may be willing to overlook antitrust activities at the request of domestic firms.

We find that richer countries, as measured by their GNI per capita, engage in less antitrust enforcement activity; specifically a 1% increase in a country’s GNI per capita reduces the relative intensity of antitrust enforcement by 1.1%. This result supports our hypothesis discussed above that as the country becomes more developed it may feel less of a need to redistribute wealth to its low income consumers through antitrust enforcement. Finally, the estimates suggest that on average countries have chosen to engage in more antitrust activity over time.

Results in Columns 2–4 of Table 5 suggest that there may be some interesting differences in the determinants of specific types of antitrust enforcement. For example, the unionization rate has a statistically significant impact only on the number of merger cases undertaken by country, not on discretionary cases such as those involving monopolization or illegal agreements. Contrary to the discussion above, this result suggests that unions do not necessarily impose pressure on governments to undertake antitrust actions; the positive impact on merger enforcement may simply reflect a correlation between union density and merger activity in the economy.

Interestingly, the parameter estimates suggest that countries engage in fewer illegal agreement cases as they privatize more of their sectors. Specifically, a 1% increase in the privatization index reduces the number of illegal agreement cases by 7.9%. This may suggest that public or pseudo-public entities may engage in more illegal activities, or these entities may pressure antitrust enforcement officials to pursue more illegal activities by their private competitors.

Abuse of dominance (or monopolization) cases seem to be the only type of antitrust case related to business cycles. The estimates suggest that a 1% increase in a country’s GDP growth rate results in an 8.8% increase in abuse of dominance cases undertaken by countries. Note that this result is contrary to the result in Ghosal and Gallo (2001),Footnote 22 who found that antitrust enforcement activity was counter-cyclical in the United States. Abuse of dominance cases are not statistically significantly impacted by the corruption levels in the country, nor by the level of development of the country.

The results described above are robust to changes in both our sample and the definition of our dependent variable. For example, parameter estimates from regressions excluding the two most prolific antitrust enforcement agencies, Poland and Ukraine, were qualitatively the same as those presented here. Similarly, the results from specifications using the number of antitrust cases as the dependent variable were virtually identical to those in which the dependent variable was the number of cases divided by the economic size of the country.

In order to better estimate the impact of time-invariant and nearly time-invariant variables, Table 6 presents the results of the fixed effects vector decomposition model. The results from those variables with significant time-variation are not qualitatively different from those presented in Table 5. However, a number of those nearly time-invariant variables that were insignificant in the fixed effect model prove to be statistically significant when estimated using the vector decomposition model.

Specifically, results suggest that countries that have undertaken more privatization engage in less antitrust enforcement activity. Perhaps more importantly, the fixed effects vector decomposition model allows us to include one additional time-invariant variable, the share of firms in each country reporting that they had 3 or fewer competitors in 1999. Not surprisingly, estimates suggest that the more concentrated industries are in a country, the more cartel-type cases a country pursues. Specifically, a 1% increase in the share of firms with 3 of fewer competitors increases the number of illegal agreement cases by 3.0%; increased market concentration may lead to a greater number of attempts at collusive activity, some of which are then detected by the authorities. This variable did not have a statistically significant impact on other types of antitrust enforcement.

6 Conclusion

While others have examined the implementation of antitrust/competition laws in post-socialist economies in the 1990s or thethe stringency of their enforcement in later periods, no previous study has attempted to explain this enforcement activity in terms of economic and political variables. Our results are somewhat preliminary given the limitations of available data, but some findings are quite interesting. Not surprisingly, those with antitrust laws adopted earlier bring more cases. While not always statistically significant, both more unionization and less corruption are associated with greater antitrust enforcement of all types.

Countries more successful in privatizing have filed fewer cases—perhaps because newly privatized firms pursue more competitive behavior than government-owned or quasi-public firms, or because governments with fewer state-holdings are less likely to be pressured to go after their private competitors. The business cycle seems not to have a major impact on case-filing activity, nor does the relative size of government in the economy. More affluent or developed countries investigate fewer cases of all types, consistent with an income-shifting motivation for antitrust. However, the more traditional welfare loss argument for antitrust activity is supported in the finding that economies with more concentrated industries bring more cases against horizontal (cartel-type) agreements.

What would be useful in future work in this area is the disaggregation of antitrust cases by industry focus, along with measures of success in antitrust enforcement (rather than simply cases investigated as examined here). Comparing the patterns found here to what has transpired after EU accession would be of interest as well. Nevertheless, we have found that while political pressures—related to unionization and state ownership—may have influenced competition policy enforcement in the post-socialist economies, reduced public sector corruption and a response to market concentration have played roles as well.

Notes

By this term we mean both post-Soviet republics and countries more generally thought of as part of Central and Eastern Europe.

These are Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Ukraine. We have excluded countries of Central Asia and Russia and the Caucasus.

Siegfried (1975) also found some evidence suggesting a reverse causalilty problem in the earlier work, in that measured welfare losses seemed more closely related to past case filing activity.

Fingleton et al (1996) focus on the experience of just four major countries (Hungary, Poland, Czech and Slovak Republics), while Dutz and Vagliasindi (2000) examine 22 economies and test for (and find) a positive relationship between implementation of competition policy and a measure of the intensity of market competition in these economies.

Romania implemented its legislation in 1996, Croatia in 1995.

A significant amount of funding for competition policy development has also come from the US, with attendant impacts on the form of policy. But the major influence has been from EU policy, particularly in the EU accession states. Significant differences continue to exist, however, among countries, as will be seen below.

These have been renumbered Articles 101 and 102 of the Treaty of Lisbon as of December of 2009.

Much of the following description is based on Global Competition Review (2009).

An exception is a new (2009) competition law in Bulgaria, which transfers to Parliament the right to appoint the head of the Commission for the Protection of Competition and elect its members.

The relevant websites are, in country alphabetical order: www.cpc.bg, www.aztn.hr, www.compet.cz, www.gvh.hu, www.konkuren.lt, www.uokik.gov.pl, www.competition.ro, www.antimon.gov.sk, www.uvk.gov.si, www.amc.gov.ua.

As noted earlier, there has been some prior research on the determinants of EU competition policy. Feinberg and Reynolds (2010) discuss U.S. state level antitrust case determinants; while antitrust is an important enforcement activity for many state Attorneys General, the types of cases pursued and level of activity is clearly influenced by the presence of federal government enforcement efforts.

We thank Viktorija Aleksiene, Kamila Acholonu-Boruc, Stan Vornivitsky, and Adina Tatar for their help in obtaining information on numbers of antitrust cases pursued.

We control for this great variability across countries by running some regressions without Poland and Ukraine.

Results from specifications that utilize the country’s unemployment rate in place of its GDP growth rate were not qualitatively different from those presented here.

On the other hand, the government-controlled firms may encourage antitrust enforcers to pursue their private sector rivals thus increasing the level of antitrust enforcement.

Countries are assigned a “1” if there is little private ownership, “2” if there is a comprehensive scheme almost ready for implementation and some sales completed, “3” if more than 25 per cent of large-scale enterprise assets are in private hands or in the process of being privatized, and a “4” if more than 50% of state-owned enterprise and farm assets are in private ownership.

The authors thank Lucio Baccaro for providing this information.

Specifically, the Heritage Foundation calculates the Government Spending Index as \( 100 - 0.03 * {\left( {\frac{{Expenditures}}{{GDP}}} \right)^2} \).

However, it is consistent with results for EU cases found by Gual and Mas (2008).

References

Areeda PA (1994) Antitrust policy. In: Feldstein M (ed) American economic policy in the 1980’s. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Besanko D, Spulber DF (1989) Antitrust enforcement under asymmetric information. Econ J 99:408–425

Boner RA, Kovacic WE (1997–1998) Antitrust Policy in Ukraine, 31 George Washington. J Int Law Econ 1

Carree M, Günster A, Schinkel MP (2010) European antitrust policy 1957–2004: an analysis of commission decisions. Rev Ind Organ 36(2):97–131

Davies SW, Driffield NL, Clarke R (1999) Monopoly in the UK: what determines whether the MMC finds against the investigated firms. J Ind Econ 47:263–283

Duso T, Neven DJ, Röller LH (2007) The political economy of european merger control: evidence using stock market data. J Law Econ 50:455–489

Dutz MA, Vagliasindi M (2000) Competition policy implementation in transition economies: an empirical assessment. Eur Econ Rev 44:762–772

EBRD (2004) Transition Report (London, EBRD)

Feinberg RM, Meurs M (1994) Privatization and antitrust in Eastern Europe: the importance of entry. Antitrust Bull 39(3):797–811

Feinberg RM, Reynolds KM (2010) The determinants of state-level antitrust enforcement. Rev Ind Organ 37(3):179–196

Fingleton J, Fox E, Neven DJ, Seabright P (1996) Competition policy and the transformation of Central Europe. CEPR: London

Ghosal V, Gallo J (2001) The cyclical behavior of the department of justice’s antitrust enforcement activity. Int J Ind Organ 19:27–54

Global Competition Review (2009) The handbook of competition economics 2009. Global Competition Review, London

Godek P (1992) Protecting Eastern Europe from antitrust. Regulation, Fall

Gual J, Mas N (2008) Industry characteristics and anti-competitive behavior: evidence from the EU. Working paper, IESE business school, January

Harrington JE Jr (2004) Cartel pricing dynamics in the presence of an antitrust authority. Rand J Econ 35(4):651–673

Holscher J, Stephan J (2004) Competition policy in central and Eastern Europe in light of EU accession. J Common Mark Stud 42(2):321–345

Holscher J, Stephan J (2009) Competition and antitrust policy in the Enlarged European Union: a level playing field? J Common Mark Stud 47(4):863–889

Hylton K, Deng F (2006) Antitrust around the world: an empirical analysis of the scope of competition laws and their effects. Boston University Law School Working Paper no. 06–47, Boston

Lauk M (2003) Econometric analysis of the decisions of the german cartel office. Working Paper, University of Technology, Darmstadt, May

Long WF, Schramm R, Tollision R (1973) The economic determinants of antitrust activity. J Law Econ 16(2):351–364

Masson RT, Reynolds RJ (1977) Statistical studies of antitrust enforcement: a critique. American Statistical Association Proceedings (Business and Economic Statistics Section), Part I

Nicholson MW (2008) An antitrust law index for empirical analysis of international competition policy. J Competition Law and Economics, published online

Ordover J, Pittman R, Clyde P (1994) Competition policy for natural monopolies in a developing market economy. Econ Transit 2:317–344

Pittman R (1992a) Some Critical Provisions in the Antimonopoly Laws of Central and Eastern Europe. Int Lawyer 26:485–503

Pittman R (1992b) Antitrust and the political process. in: Audretsch DB, Siegfried JJ, eds. Empirical studies in industrial organization: essays in honor of Leonard W. Weiss. Kluwer

Pittman R (1998) Competition law in central and eastern europe: five years later. Antitrust Bull 43(1):179–228

Pittman R (2004) Abuse-of-dominance provisions of Central and Eastern European competition laws: have fears of over-enforcement been borne out? World Competition 27(1):245–257

Plumper T, Troeger VE (2007) Efficient estimation of time invariant and rarely changing variables in finite sample panel analysis with unit fixed effects. Polit Anal 15(2):124–139

Siegfried JJ (1975) The determinants of antitrust activity. J Law Econ 18:559–574

Stotyka Y (2006) Antitrust in Ukraine. In: Moriarti P (ed) Anti trust policy issues. Nova Science, New York

Wood BD, Anderson JE (1993) The politics of U.S. antitrust regulation. Am J Polit Sci 37(1):1–39

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Feinberg, R.M., Meurs, M. & Reynolds, K.M. Maintaining New Markets: Explaining Antitrust Enforcement in Central and Eastern Europe. J Ind Compet Trade 12, 203–219 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-011-0095-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-011-0095-4