Abstract

Data for mental health disorders and its relation to work and family issues in Egypt are scarce. We conducted this cross-sectional study among 1021 participants aged 18–59 years from Minia, Upper Egypt to measure the prevalence of mental health disorders and their associations with work-family conflict. Mental disorders were assessed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatry Interview (MINI-Plus) diagnostic interview and work-family conflict was assessed by the National Study of Midlife Development in the US. Work-to-family conflict (WFC) was associated with a 5.2% increase in the probability of mental health disorders; the multivariable-adjusted OR (95% CI) in subjects with high versus low WFC was 2.26 (1.18–4.34). On the other hand, there was a 2.0% increase in the probability of mental health disorders with high family-to-work conflict (FWC); OR (95% CI) was 1.37 (0.78–2.41). One point increment in the total score of work-family conflict was associated with a 3.4% increased probability for having a mental health disorder. The highest probabilities for having mental disorders were found among participants whose jobs require a lot of travel away from home (3.4%) or take much energy (3.5%) and among those whose family activities stop them from getting the amount of sleep needed to do their jobs (3.4%).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The work and family environments shape one’s physical, social, and mental health behaviors (Fellows et al. 2016). The interaction between work and family circumstances towards health is documented in many previous studies (Eshak et al. 2018; Fellows et al. 2016; Tuttle and Garr 2009; Chandola et al. 2004). When the role demands of one discipline (work or family) are incompatible with the role demands of the other discipline, work-family conflict originates (Huang et al. 2004). The direction of such interface, whether work-to-family (WFC) or family-to-work (FWC) depends on which discipline (work or family) infringed on the rights of the other discipline.

The associations between work environment and employees’ mental health are well-established (Wang 2005; Huang et al. 2004); meanwhile, there is a growing body of evidence for the impact of family environment on psychological health (Eshak et al. 2017; Glavin and Peters 2015; Barmola 2013; Chandola et al. 2004). Between work and family, there are competing interests that could lead to both physical and mental disorders by many pathways. These pathways include the loss of resources (e.g., reduced time for sleep in one hand or reduced time or energy for work and thus less job security or rewards on the other hand); adopting bad coping strategies (such as physical or mental unhealthy behaviors); and having poor relationship quality (e.g. less social support at work or at home) (Eshak et al. 2018; Kobayashi et al. 2017; Fellows et al. 2016; Minnotte et al. 2015; Barmola 2013; Karimi and Nouri 2009; Chandola et al. 2004).

Although numerous research studies on the impact of work-family conflict on health outcomes have been conducted globally (Eshak et al. 2018; Kobayashi et al. 2017; Glavin and Peters 2015; Barmola 2013; Tuttle and Garr 2009; Chandola et al. 2004), we lack such literature for the Egyptian population who has been facing the stress of ongoing economic reform since 2013 (Ricz 2019). Such reform has its implications not only on family stability, with more marital problems (Schieman and Young 2011) leading to increased divorce rate, but also in the work environment as indicated by the increased unemployment rate (Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics 2017). The author started to investigates the impact of prevailing work-family conflict on Egyptians’ health status, documenting the associations between work-family conflict and self-rated health (Eshak et al. 2018) and sleep disorders (Eshak 2018). In this research, the investigation has been directed toward mental health. The aim of this study is to investigate the prevalence of mental health disorders among residents of Upper Egypt, and to identify the associations between work-family conflicts and these disorders.

Methodology

Study Design and Participants

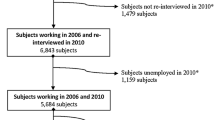

This is a cross-sectional study conducted between June–July, 2017 among residents of Minia district in Upper Egypt. The final sample, after excluding 179 subjects who refused to participate or were under treatment of chronic diseases, included 1201 men and women aged 18–59 years (the working age) recruited by house-to-house visits via a systematic random sample technique in both urban and rural areas of Minia district in Upper Egypt. The sampling methods and protocols of the study were previously described in detail (Eshak et al. 2018).

Data Collection Tools

Work-Family Conflict

WFC and FWC were measured by two four-item sets of the National Study of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) (Grzywacz and Marks 2000). In each set, a three scale assessment was applied (0 = never, 1 = to some extent, 2 = often) for each of the four items. The sum of the following four items (ranged from 0 to 8) assessed the WFC (a) “Your work involves a lot of travel away from home”; (b) “Your job reduces the amount of time you can spend with the family”; (c) “Problems at work make you irritable at home”; and (d) “Your job takes so much energy; so, you do not feel up to doing things that need attention at home”. The sum of the following four items (also ranged from 0 to 8) assessed the FWC (e) “Family matters reduce the time you can devote to your job”; (f) “Family activities stop you getting the amount of sleep you need to do your job well”; (g) “Family obligations reduce the time you need to relax or be yourself” and (h); “Family worries about problems distract you from your work”.

The cutoff points that differentiated low and high levels of WFC and FWC were the median of each score (3 for WFC and 2 for FWC). Stratifying by these median values yielded a four-category variable with these groups (a) low WFC and low FWC; (b) high WFC and low FWC; (c) low WFC and high FWC; and, (d) high WFC and high FWC. The internal consistency of the scale items was 0.78 by Cronbach’s alpha test.

Mental Health Disorders

The Mini International Neuropsychiatry Interview (MINI-Plus) brief structured interview which was designed for the major Axis I psychiatric disorders in ICD-10 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (Sheehan et al. 1998) were used to assess mental health disorders. The validity and reliability of the MINI-Plus were tested against other diagnostic tools of mental health disorders and showed high validation and reliability scores despite being applicable to a shorter period of time (Sheehan et al. 1998). Trained staff administered selected sections of the Arabic version of the MINI-Plus instrument for diagnosis of mental health disorders (Ghanem et al. 2009; Ghanem 1999). The selected sections included: somatoform disorders, psychotic disorders, multiple disorders, major depressive episode for mood disorders, and generalized anxiety for anxiety disorders.

Covariates

Data on medical histories, including histories of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and smoking habits were also collected, in addition to the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants such as sex, age, residency, marital status, education, and occupation.

Statistical Analysis

The risk factors for mental health disorders, levels of perceived WFC and FWC, and other participants’ characteristics are shown as numbers and percentages in subject both with and without mental health disorders using the SAS software proc means for continuous variables and proc freq for categorical variables. The significance of age-adjusted differences in these variables among both groups, with and without mental disorders, were tested by the chi square test. The proc logistic descending statement was used to run logistic regression analysis that was conducted to assess the relationship of WFC, FWC, and work-family conflict with the risk of having mental health disorders. The multivariate models were adjusted for sex, age, residence, marital status, sleep duration, monthly income, occupation, employment status, and education. The final model was further adjusted for smoking habit and histories of hypertension and diabetes. Also, the Proc qlim statement was applied to calculate the average marginal effects (β % change in the probability of having mental health disorders) besides the odds ratios (ORs) with its respective (95% CIs) for risk of mental health disorders by one point increment in each of WFC/FWC and total work-family conflict scores. Then, we tested the risk separately for each of the eight components that measured the work-family conflict in the MIDUS. In stratified analyses, we checked if there will be any effect modification by a wide range of covariates (age, gender, residence, education, income and marital status) by adding to the model a cross product term of the variable for stratification and the work-family conflict variable. All statistical tests were two-tailed with p value < 0.05 considered statistically significant and conducted by SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The syntax and full results of the econometric analyses are available upon request from the first author.

Results

Among 1021 residents of Upper Egypt, the prevalence of mental health disorders was 6.7%. A comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of the current study sample with those for residents in Minia governorate and the whole of Egypt is given in Table 4 in Appendix 1. As shown in Table 1, the proportions of having high WFC and FWC were higher in subjects with mental health disorders than the respective proportions in subjects without mental health disorders. Moreover, compared to participants without mental health disorders, those with mental health disorders were younger and more likely to be highly educated, unemployed, divorced or widowed, current smokers, and having histories of hypertension or diabetes.

The average marginal effects of having a mental health disorder were 0.052 and 0.020 for high levels of WFC and FWC, respectively; however, the OR was statistically significant for WFC: [OR = 2.26 (95%CI: 1.18–4.34)] but not for FWC: [OR = 1.37 (95% CI: 0.78–2.41)]. A one point increment of the total score of family-work conflict was associated with a 3.4% increased probability for having a mental health disorder (Table 2).

When the risk of having mental health disorders was tested for each component of the family-work conflict items of the MIDUS tool, there was an approximate 3.5% increased probability of having a mental health disorder for each of these categories: participants whose work requires frequent travels away from home, those whose work takes much energy, and those whose amount of sleep required to do their jobs, was reduced due to family activities (Table 3). There were no significant interactions between the participants’ characteristics and work-family conflict toward the risk of mental health disorders, except for a significant higher risk of currently married subjects with high WFC as shown in Table 5 in Appendix 2.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of 1021 Upper Egyptian men and women of working age, the prevalence of mental health disorders was 6.7%. We found that the high level of WFC was associated with a 5.2% increased probability of mental disorders, while a 2.0% increased probability was observed among subjects with high levels of FWC. Moreover, the risk of mental health disorders increased by 3.4% for each one point increment in total score that combined both WFC and FWC items, and a similar increased probability was observed among participants with frequent business travels away from family, participants who put much energy in their jobs, and participants whose family issues deprive them from having enough sleep to do their jobs. These associations were independent of the participants’ medical histories and socioeconomic characteristics.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to measure the burden of mental health disorders in Upper Egypt, and the first to investigate the association between work-family conflict and these disorders.

The burden of mental health disorders is increasing globally (Steel et al. 2014); an accurate prevalence is not available for most developing countries, including Egypt. Egypt suffers from shortages in mental health services and its service providers (Ghanem 2004). Moreover, expenditures on mental health are less than 1% of Egypt’s health budget (Okasha et al. 2012); Upper Egypt suffers these shortages the most (Ghanem 2004).

The cross-sectional (Shimazu et al. 2013; Panatik et al. 2011; Tuttle and Garr 2009; Hämmig and Bauer 2009; Wang et al. 2007; Chandola et al. 2004; Frone 2000) and longitudinal (Hammer et al. 2005; Frone et al. 1997) associations between work-family conflict and mental health have been addressed in Western and Asian populations, with a general trend towards a positive association. In their cross-sectional comparative study of Finland, Japan, and the UK, Chandola et al. (2004) reported significant associations between both WFC and FWC with poor mental health in both men and women of the three countries. Similar results were found in Switzerland (Hämmig and Bauer 2009), Japan (Shimazu et al. 2013), Malaysia (Panatik et al. 2011) and in some (Frone 2000; Wang et al. 2007) but not all (Tuttle and Garr 2009) the US studies. However, one longitudinal study reported no association between work-family conflict in either direction. WFC or FWC, and depression of husbands and wives (Hammer et al. 2005) while another longitudinal study (Frone et el. 1997) found that FWC, but not WFC, was associated with employed parents’ depression.

In contrast to findings from Western studies (Tuttle and Garr 2009; Hämmig and Bauer 2009; Frone 2000), but consistent with findings from studies in Japan (Shimazu et al. 2013; Chandola et al. 2004), we found a stronger impact of WFC on mental health disorders than that of FWC. The reason for these discrepancies is not clear. However, the assessments for work-family conflict were different among the studies. A single-item question was used in the Swiss study (Hämmig and Bauer 2009); two items were used in the US study (Frone 2000); the Survey Work-home Interaction-NijmeGen (SWING) with eight items for WFC and four for FWC was used in the Japanese study (Shimazu et al. 2013); that present study, like the comparative study in Finland, Japan, and the UK (Chandola et al. 2004) used the MIDUS diagnostic criteria with four items to capture each of the WFC and FWC. Moreover, both the mental health disorders studied and the diagnostic methods varied among the above-mentioned studies: a single-item measure for each of depression, optimism, fatigue, and sleep disorders was used in the Swiss study (Hämmig and Bauer 2009); the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) was used to diagnose mood, anxiety, substance use, and other disorders in the US studies (Wang et al. 2007; Frone 2000); the SF-36 mental health component score (MCS) was used to measure mental health in the comparative study (Chandola et al. 2004); psychological distress, measured with the Kessler 6 questionnaire, and social undermining, measured with the Abbey scale, were uesed in the Japanese study (Shimazu et al. 2013).

Frone (2000) postulated that individuals may attribute the reasons for WFC externally, blaming the employing organization and attribute the reasons for FWC internally, blaming themselves. Although these differences in attributions of responsibility for work-family conflict in the two directions could translate to a stronger association between mental health disorders and FWC rather than WFC among the Americans in the National Comorbidity Survey (Wang et al. 2007; Frone 2000), this theoretical framework is not consistent with the findings from Middle Eastern countries as shown in both our study and in an eariler Iranian study (Karimi and Nouri 2009). The strong commitment to their families’ responsibilities and the strong family ties may drive Egyptians whose work infringed on the rights of their family to have higher risk of sleep disorders (Eshak 2018) as well as mental health disorders.

This is the first study in Africa and the Middle-East region to investigate the associations between work-family conflict and risk of mental health disorders. However, notable limitations of this study include the cross-sectional design with its inability to infer causality, the relatively small sample size that could have led to insufficient power to capture significant associations between FWC and mental health disorders despite the evident increased risk, and the lack of data on number of children or pattern of care giving in the family affect both work-family conflict and mental health (Glavin and Peters 2015). It is also noted that the respondents in the current study showed some dissimilarity with the general population characteristics in Egypt. However, the observed difference in the age distribution is attributed to our inclusion criteria to recruit residents of working age (18–59 years); whereas that for the high share of female workers in our sample is attributed to considering housewives, who worked alone or with their husbands in farming, technical or manual work, as having a job. Women constitute 53% of the total domestic service labor force in Egypt; they tend to work in home industries, either as own-account workers or as family aids; almost half of them work in family industry that does not require working outside the home (Tucker 1976). The self-reported data is another limitation; however, data on work-family conflict were collected via a complex scoring algorithm, rather than a single-item question, and the mental health disorders were diagnosed via a validated tool. Due to a shortage of funds and facilities, we investigated eight mental health disorders in our study. Thus, the detected prevalence (6.7%) of the total mental health disorders in our sample was lower than that (16.9%) reported in a preliminary national survey, which investigated 20 mental health disorders among 14,640 adults (aged 18–64) from five governorates of Lower Egypt (Alexandria, Giza, Qaliubia, Fayoum and Isamilia) (Ghanem et al. 2009).

In summary, work-family conflict was associated with higher risk of mental health disorders among residents of Upper Egypt. Further large-scale research is needed to confirm the associations between work-family conflict and physical and mental health among Egyptian civil workers and its effects on their work productivity.

References

Barmola, K.C. (2013). Family environment, mental health and academic performance of adolescents. International Journal of Scientific Research, 2277–8179, 531–533. https://doi.org/10.15373/22778179/dec2013/169

Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) (2017). Annual statistical book of 2017. http://www.t-series.capmas.gov.eg/pdf/book_year/YearBook_1910.pdf

Chandola, T., Martikainen, P., Bartley, M., Lahelma, E., Marmot, M., Michikazu, S., et al. (2004). Does conflict between home and work explain the effect of multiple roles on mental health? A comparative study of Finland, Japan, and the UK. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 884–893. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh155.

Eshak, E. S. (2018). Work-to-family conflict rather than family-to-work conflict is more strongly associated with sleep disorders in Upper Egypt. Industrial Health. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2018-0091.

Eshak, E. S., Iso, H., Honjo, K., Noda, A., Sawada, N., Tsugane, S., et al. (2017). Changes in the living arrangement and risk of stroke in Japan; does it matter who lives in the household? Who among the family matters? PLoS ONE, 12(4), e0173860. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173860.

Eshak, E. S., Kamal, N. N., Seedhom, A. E., & Kamal, N. N. (2018). Work-family conflict and self-rated health among dwellers in Minia, Egypt: Financial strain vs social support. Public Health, 157, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.01.016.

Fellows, K. J., Chiu, H. Y., Hill, E. J., et al. (2016). Work-family conflict and couple relationship quality: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 37, 509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9450-7.

Frone, M. R. (2000). Work-family conflict and employee psychiatric disorders: The national comorbidity survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 888–895. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-90I0.85.6.888.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, L. (1997). Relation of work-to-family conflict to health outcomes: A four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70, 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00652.x.

Ghanem, M. (1999, March). Development and validation of the Arabic version of the mini international neuropsychiatry interview (MINI). Paper presented at the Annual International Conference of the Egyptian Psychiatric Association, Cairo, pp.24–26.

Ghanem, M. (2004). Psychiatric services and activities in the ministry of health and population. Journal of the Egyptian Psychiatric Association, 23(2), 16–9. Retrieved from http://new.ejpsy.eg.net/aboutus.asp

Ghanem, M., Gadallah, M., Meky, F.A., Mourad, S., El-Kholy, G. (2009). National survey of prevalence of mental disorders in Egypt: preliminary survey. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 15(1), 65–75. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/117609

Glavin, P., & Peters, A. (2015). The costs of caring: Caregiver strain and work-family conflict among Canadian workers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36, 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9423-2.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: an ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1037//I076-8998.5.1.11I.

Hammer, L. B., Cullen, J. C., Neal, M. B., Sinclair, R. R., & Shafiro, M. V. (2005). The longitudinal effects of work-family conflict and positive spillover on depressive symptoms among dual-earner couples. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.138.

Hämmig, O., & Bauer, G. (2009). Work-life imbalance and mental health among male and female employees in Switzerland. International Journal of Public Health, 54(2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-8031-7.

Huang, Y. H., Hammer, L. B., Neal, M. B., et al. (2004). The relationship between work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25, 79. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JEEI.0000016724.76936.a1.

Karimi, L., & Nouri, A. (2009). Do work demands and resources predict work-to-family conflict and facilitation? A study of Iranian male employees. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30, 193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-009-9143-1.

Kobayashi, T., Honjo, K., Eshak, E. S., Iso, H., Sawada, N., Tsugane, S., et al. (2017). Work-family conflict and self-rated health among Japanese workers: How household income modifies associations. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0169903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169903.

Minnotte, K. L., Minnotte, M. C., & Bonstrom, J. (2015). Work-family conflicts and marital satisfaction among US workers: Does stress amplification matter? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36, 21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9420-5.

Okasha, A., Karam, E., Okasha, T. (2012). Mental health services in the Arab world. World Psychiatry, 11(1),52–4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41858461

Panatik, S. A. B., Badri, S. K. Z., Rajab, A., AbdulRahman, H., & Shah, I. M. (2011). The impact of work family conflict on psychological well-being among school teachers in Malaysia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 1500–1507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.390.

Ricz, J. (2019). New developmental experiments in two emerging economies: Lessons from Brazil and Egypt. In T. Gerőcs & M. Szanyi (Eds.), Market liberalism and economic patriotism in the capitalist world-system., International Political Economy Series Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schieman, S., & Young, M. (2011). Economic hardship and family-to-work conflict: The importance of gender and work conditions. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32, 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9206-3.

Sheehan, D.V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K.H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., et al. (1998). The mini international neuropsychiatry interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59 Suppl 20, 22–33; quiz 34-57. Retrieved from https://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/Pages/home.aspx

Shimazu, A., Kubota, K., Bakker, A., Demerouti, E., Shimada, K., & Kawakami, N. (2013). Work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict among Japanese dual-earner couples with preschool children: A spillover-crossover perspective. Journal of Occupational Health, 55(4), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.12-0252-oa.

Steel, Z., Marnane, C., Iranpour, C., Chey, T., Jackson, J. W., Patel, V., et al. (2014). The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 476–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu038.

Tucker, J. (1976). Egyptian women in the work force: An historical survey. Middle East Reports, 50, 3–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/3010883.

Tuttle, R., & Garr, M. (2009). Self-employment, work–family fit and mental health among female workers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30, 282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-009-9154-y.

Wang, J. (2005). Work stress as a risk factor for major depression. Psychological Medicine, 35, 865–871. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291704003241.

Wang, J., Afifi, T. O., Cox, B., & Sareen, J. (2007). Work-family conflict and mental disorders in the United States: Cross-sectional findings from the national comorbidity survey. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 50(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20428.

Acknowledgements

The author would extend thanks to the fourth grade medical students in Minia University who have helped in data collection.

Funding

No specific funds were received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and was approved by Minia University research ethics committee.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eshak, E.S. Mental Health Disorders and Their Relationship with Work-Family Conflict in Upper Egypt. J Fam Econ Iss 40, 623–632 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09633-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09633-3