Abstract

Understanding the effects of power distribution, particularly women’s decision making, on human development is important. This study used a set of direct measures of decision-making power from the Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurement Survey and examined the relationship between women’s decision-making power and the food budget share, nutrition and child schooling. It found that in Pakistan, the relationship between women’s decision-making power and nutrition was not linear and varied depending on rural or urban residence. There was no clear evidence that higher women’s decision-making power would lead to better nutrition availability in Pakistan, but overall households were more likely to consume less grain and more vegetables. When women had higher decision-making power, children, particularly rural girls, were more likely to be enrolled in school.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

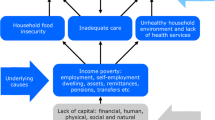

Households are central to most policy initiatives aimed at reducing poverty because a significant portion of economic activities occur within households. This is particularly important in developing countries, since significant efforts are focused on finding the most efficient and effective ways to transfer income and other resources to poor households. When deciding where to direct welfare benefits with the aim of increasing household well-being, it is necessary to understand the effects of power distribution within the households to which the aid is directed. Research in this area has provided valuable evidence to policy initiatives aimed at improving human development. Two hypotheses are involved. First, women make better decisions with regards to children’s education and nutrition; and second, a larger income or asset share increases decision making of the women within households. This paper is one of the attempts to examine the relationship between women’s decision-making power and the food budget share, nutrition and child schooling in Pakistan.

A number of the empirical studies have tested one or both of the hypotheses in the developing country context. For example, using data from the 1991/1992 and the 1998/1999 Ghana Living Standards survey, Doss (2006) showed that the share of assets owned by women in Ghanaian households affected household expenditure patterns. In particular, women’s share of farmland significantly increased budget shares on food. Schady and Rosero (2008) used a randomized design to analyze the effects of unconditional cash transfers to women on the food budget share. After the intervention, households assigned to the “treatment” group had significantly higher food shares than those assigned to the “control” group. Hoddinott and Haddad (1995) found that when women’s share of household income increased, so did the budget share spent on food; and such households also spent less on more male-specific consumption items such as alcohol and cigarettes. Similarly, Maitra and Ray (2002) found that the gender of the income earner had an important effect on expenditure share. Using the 2001 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, Allendorf (2007) examined whether women’s land rights empower women and benefit young children’s health and showed that women who owned land were significantly more likely to have the final say in household decisions. In addition, children of these mothers were significantly less likely to be severely underweight. Menon et al. (2014) used Vietnam’s 2004 and 2008 Household Living Standards Survey to analyze whether land titling for women led to improvements in child health and education. The analysis showed female-only held land-use rights decreased the incidence of illness among children, increased their health insurance coverage, raised school enrollment, and reallocated household expenditures toward food and away from alcohol and tobacco. Quisumbing and Maluccio (2003) found that in Bangladesh and South Africa, women’s assets increase was associated with higher expenditure shares on education. Maitra (2004) showed that a woman’s control over household resources had a significant effect on the demand for prenatal care and hospital delivery in India. Yusof and Duasa (2010) found in Malaysia relative earning share was a significant factor in decision making as well as consumption expenditure. Hallman (2000) showed a greater proportion of pre-wedding assets held by the mother lowered the number of morbidity days experienced by girls in rural Bangladesh.

The evidence that women have stronger preferences for child schooling, are more concerned about health outcomes, and tend to spend on collective consumption items such as food is pretty strong. However, some recent work challenged these conclusions (Basu 2006; Felkey 2013; Lancaster et al. 2006). Basu (2006), using an intra-household theoretical framework, showed that if the woman had more decision-making power than the man, the woman would have access to a greater share of the income produced by child labor and thus benefit from child labor. School enrollment might therefore decline as a result of increased child labor. Empirically, Maitra and Ray (2006) found that in South Africa, there was no clear evidence that the gender of income earners affected household expenditures; and Felkey (2013) suggested that in Bulgaria, the relationship between women’s bargaining power and household well-being was not monotonic. Hou and Ma (2012) examined women’s decision-making power and maternal health services uptake, and found that women’s decision-making power played a significant role in determining uptake of maternal health services in Pakistan.

However, in general, empirical evidence on women’s decision-making power and human development in Pakistan is quite limited. Yet, Pakistan presents a unique case to study women’s decision-making power. The prevailing traditional cultural restrictions on women often position males as the household decision-makers (Amin 1997; Hakim and Aziz 1998). But in recent years, economic growth and efforts to empower women in Pakistan have significantly improved women’s roles both within and outside of households. More women are being educated and are more involved in household decisions.

On the other hand, human development remains the key underpinning for sustained economic gains. The school enrollment rates are still low in Pakistan. The adult literacy rate is 50 % compared to a 58 % average for South Asia. Similarly, the net primary school enrollment rate for 2011 was 72 %, lower than in neighboring countries such as Sri Lanka (94 %), or India (93 %), even though it has increased from 51 to 72 % in about ten years (World Bank 2014). Significant gender differences in enrollment rates persist despite the fact that the school participation rate has increased at a higher rate for girls. The gender disparity in enrollment, completion, graduation and literacy rates is reflected at all levels of education. Female children tend to have higher dropout rates at the secondary school levels in comparison with males. Malnutrition continues to be a significant challenge. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that 38 % of Pakistani children under the age of five are underweight, while 42 % of children under-five suffer from stunting (UNICEF 2010).

Another motivation of the paper is closely linked with a flagship cash transfer program in Pakistan. In order to mitigate the impact of the 2008 food crisis, the Government of Pakistan launched a cash transfer program, the Benazir Income Support Program (World Bank 2009), which transferred Rs. 1000 per month to ever-married women in eligible poor households. Despite the political motivation of directly transferring cash to ever-married women, it was also perceived that directly transferring cash to women would also increase human development outcomes. This, however, is based on two assumptions: (1) as in other countries, giving cash directly to women can increase not only total household income, but also women’s bargaining power, as the cash transfers are perceived to be women’s additional income; and (2) higher women’s decision-making power is associated with higher human development investment within households.

Therefore, to what extent Pakistani women’s decision making is associated with human development is not just an important research question, but also an important policy question. This paper found that in Pakistan, the relationship between women’s decision-making power and nutrition was not linear and varied depending on rural or urban residence. There was no clear evidence that higher women’s decision-making power would lead to better nutrition availability in Pakistan, but overall households were more likely to consume less grain and more vegetables. When women had higher decision-making power, children, particularly rural girls, were more likely to be enrolled in school.

Data and Key Variables

Data

This study used two rounds of repeated cross-sectional data from the Pakistan Social and Living Standard Measurement (PSLM) survey, the 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 rounds respectively, to analyze the relationship between women’s decision-making power and budget share, caloric and nutrition availability, and child education. Two rounds of data were used in order to further increase the robustness of the analyses by controlling for year/round difference. The use of multiple rounds of data to increase the variation is important because household incomes and caloric intake varies due to variation of climate and agricultural production from year to year. The PSLM survey is a nationally representative survey conducted by the Federal Bureau of Statistics (FBS). It covers about 15,000 households sampled in 14 large cities and 81 districts, including urban and rural areas. A two-stage stratified sample design was adopted for both surveys. Urban population in large cities, urban population in a group of small cities, and rural population in districts were considered as separate strata. Enumeration blocks in the urban domain and mouzas/dehs/villages in the rural domain were used as primary sampling units (PSUs). Sample PSUs from each stratum/sub-stratum were selected by the probability proportional to size (PPS) method of sampling scheme. Households within each sample PSU were considered as secondary sampling units (SSUs). Using a random systematic sampling scheme with a random start, 16 and 12 households were selected from each sample village and enumeration block, respectively. Non-responsive households were replaced during the survey to ensure national representativeness. The PSLM data was used to estimate the poverty rates and used in a variety of research on Pakistan.

PSLM covers a range of social issues, including education, employment, health, immunization, women’s decision-making and household consumption. The paper used two rounds of data to control for the factors that might be correlated with year variation. Statistically, since both rounds are nationally representative, the differences between the two rounds cannot be attributed to the sample difference, rather than the yearly difference. The sample is 13,754 households for the 2005–2006 round and 13,411 households for the 2007–2008 round.

Construction of Women’s Relative Decision-Making Power (θw)

The essential element in analyzing the association between women’s decision-making power and human development is the measurement of women’s relative decision-making power in households. In the economic literature, decision-making and bargaining power are measured by the relative incomes of the male and female household heads, or by the ratio of number of school years completed by female to male heads of the households (Gitter and Barham 2008). The underlying assumption is that women who bring more income to households or women with a higher level of education are more likely to have greater bargaining power at home. However, as Basu (2006) pointed out, a measure based on income share might be endogenous to household decisions because a woman’s earnings are dependent on her being in the labor force, which is a choice variable for households and is influenced by the household’s decisions. In addition, it is inappropriate to use relative income as a measure for women’s decision making in Pakistan because the female labor force participation rate is about 10 % (Hou 2010). Should the relative earnings be used as the women’s decision-making power, most women would have decision-making power as 0. This is clearly not the case. Relative years of education or levels of education could be feasible. However, in the survey, there is no direct question about years of education; instead, the question is about level of education achieved at the broader categories as no education, class 1–5 (primary education), class 6–8 (secondary education), class 9–10 (high school) and class 11 and beyond (college and above). This design is suitable in Pakistan’s context because it may take some people multiple years to finish one academic year for various reasons. Despite the unavailability of information on years of education, level of education is a pre-existing condition, most likely before marriage, but women’s bargaining is a more dynamic process after marriage, often related to the wealth level of a woman’s natal household.

One contribution of this study is the ability to use a set of more direct measures of decision-making power from the PSLM Survey, which directly asks the married women who, in the household, makes decisions on key issues, including expenditures. Such measurement captures the broader contributing factors to women’s decision making beyond income and education, as argued in social science literature (Adato et al. 2003) and provides a more direct estimate of how women’s decision-making power affects some key household human development outcome. A few studies were able to use this measure. For example, Hou and Ma (2012) used the same set of measures to test women’s decision-making power and maternal health services utilization in Pakistan; and Friedberg and Webb (2006) used data on whether a husband or wife, in the Health and Retirement Study, “has the final say” when making major decisions in a household as an indicator for decision making.

There are eight questions in the PSLM regarding household decision-making about women’s education, employment, birth control methods, having more children, and household food, clothing, medical treatment, and recreation expenditures. Only female heads of the households are asked these questions, and they are interviewed by female enumerators without the presence of husbands or male heads of households.Footnote 1 The answers to these questions can be broadly categorized as “woman decides alone,” “household head or husband decides alone,” “household head or husband and woman jointly decide,” and “other family members decide.” Since the respondents are married women, the question about education most likely reflects the decision-making dynamics in each woman’s family of birth, and thus has limited relevance in her current situation. The questions regarding employment are relevant; however, the labor force participation rate is only about 10 % for females in Pakistan (Hou 2010). Since the low labor force participation rate is driven more by the overall culture and the extremely limited job opportunities for women in most areas of Pakistan, rather than by women’s decision-making power within the households, I did not include these questions in the construction of the decision-making index. The third and the fourth questions are about birth control methods and number of children. These two questions are important in measuring women’s decision-making power. However, in Pakistan, these two measures probably only become relevant in decision making after the birth of at least one son (Hamid et al. 2009, 2010). Thus, in families still trying to achieve the desired goal of having at least one son, women could perceive their decision-making power as either active or obedient. Since it is impossible to directly factor these concerns in the construction of the decision-making power index, these two questions were not included either.

As a result, the analysis of women’s decision-making power was constructed on the basis of four questions about household expenditures on food, clothing, medical treatment, and recreation. If a woman makes the decision by herself, she was considered to have decision-making power equal to 1; if a woman “jointly makes the decision,” she was considered to have decision-making power equal to 0.5; if a woman was not involved at all in the decision making, she was considered to have decision-making power equal to 0. The composite score for each woman (ψw) was constructed by adding the scores from the four questions. The composite score for each household male head (ψm) was constructed in a similar way.Footnote 2 The scale for both scores ranges from 0 to 4. Women’s relative decision-making power (θw) was constructed using the share of the women’s decision-making (θw = ψw/(ψw + ψm)). The average of θw is presented in the first row of Table 7 in Appendix. The average of θw is 0.31 in the household sample, respectively, with the standard deviation as 0.33. The t test results show that women had significantly less decision-making power than men in Pakistan’s households.Footnote 3 The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient is 0.9024, showing excellent internal consistency (Cronbach 1951; George and Mallery 2003).

One limitation of this measurement is that the constructed women’s decision-making index is solely based on women’s answer to “who in the households make the decisions,” rather than answers from both men and women. Thus the construction could be biased. However, the direction of the bias is hard to determine. From the theoretical point of view, women might over-report or under-report their decision-making in the households; but empirical tests would require data collection from both women and men of the households to test the consistency of the answers. Despite these limitations, the construction of this women’s decision-making power index offers almost the first quantitative analysis of this issue in Pakistan. This feeds into the imperative policy needs to better understand the relationship between women’s decision-making power and human development as part of the cash transfer policy design in Pakistan.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship of women’s decision-making power and log per capita expenditure. It clearly shows women’s decision-making power was positively correlated with log per capita expenditure.Footnote 4 Because the possible co-linearity between the log per capita expenditure and women’s decision making, asset quintile was used to control for the wealth effect in the linear regression. Asset index better captures the permanent income, rather than the transient income.

Caloric and Nutrition Conversion, and School Enrollment

In the consumption module, the survey collected data on the quantities and values of 58 consumed staple food either based on a 14 day or month recall, depending on the item. Self-reported consumed quantities of 58 staple food items in the PSLM were converted to caloric and nutrition measures based on nutritional values in Pakistan, to represent household-level caloric availability; fortnightly measures were converted to monthly consumption. In addition to total caloric availability, caloric information was also disaggregated to calories obtained from grains, vegetables, fruit, and animal products (including dairy products and meat).

School enrollment is measured as the percentage of children who are enrolled in school out of the total number of children in that household. For boys and girls school enrolment, similar measures were constructed. This measure avoids the cluster problems in the regression analyses should the individual enrollmentFootnote 5 be used as the dependent variable.

Theoretical Framework and Research Methods

Two household models were used to study intra-household bargaining and the decisions on child schooling, labor, and the allocation of consumption expenditures between private and public goods: classic unitary models and newer collective models. The former models are typically based on the notion that household preferences can be characterized by a single utility function; they assume either that there is a dictator or that household members have the same preferences and pool their resources to maximize the single utility function (Becker 1981). The collective models assume that different household members have distinct preferences and that final decisions fall somewhere along the spectrum between full cooperation and conflict, particularly when male and female heads of household are the decision makers (Basu 2006; McElroy and Horney 1990).

In Pakistan, the unitary model would seem to fit because the prevailing traditional cultural restrictions on women (Amin 1997; Hakim and Aziz 1998) often position the male head as the household decision maker. However, due to economic growth and efforts to empower women in Pakistan in recent years, women’s roles have improved both within and outside households. More women are being educated and are more involved in their employment decisions. Thus, in this context, a collective model is also plausible and the household human development investment is a function of women’s decision-making power.

The Lowess non-parametric method was used to examine the relationships between the dependent variables of interests (budget share, caloric and nutrition availability, and child school enrollment) and women’s decision-making power, after adjusting for per capita expenditure. Locally weighted scatter plot smoothing, proposed by Cleveland (1979), is an outlier-resistant method based on local polynomial fits. It provides a generally smooth curve, the value of which at a particular location along the X-axis is determined only by the points in that vicinity. It is more flexible than parametric fitting and can fit any pattern of data. The Y-axis is the residual after regressing dependent variables on per capita expenditure. Per capita expenditure needed to be adjusted because of the significant correlation with women’s decision-making power and with most dependent variables.

Lowess makes few, if any, assumptions about the relationship between women’s decision-making power and dependent variables and can reveal unexpected patterns and departures from linear assumptions. However, without parameters, there is no quantitative interpretation of effects or relationships, and it is difficult to incorporate substantive statistical tests. Therefore, parametric estimation was also used to complement the nonparametric method. Using repeated cross-section data, I quantified and tested the significance of the relationship between women’s decision-making power and various human development indicators using the following equation:

in which, Y is the outcome variable, X is a set of covariates, t is the survey round dummy variable, and ε is the stochastic error term. Some recent literature (Basu 2006; Felkey 2013; Lancaster et al. 2006) showed that the relationships between women’s decision-making power and outcome variables are neither linear nor monotonic. Therefore, both linear and quadratic terms were included in the regression. The variables X in the equation included household size, demographic and educational characteristics of the household head, household demographic composition variables, and dummies for region. The asset index quintiles were used in the regression as proxy for household wealth because per capita expenditure and per capita caloric availability were measured from the same month while asset index was a much smoothed indicator for household permanent wealth. Multicollinearity and heterosokedasticity tests were conducted after each regression and presented in the regression tables.

Results

Food Budget Share and women’s Power

The first graph in Fig. 2 depicts the relationship between food expenditure share and θw, after controlling for per capita consumption. An earlier draft of the paper included the budget share on footwear, clothing and education (Hou 2011). However, since these dependent variables accounted for less than 10 % of the total expenditure and the regression model showed significant heteroskedasticity, the results of those budget expenditure categories are not presented here. The regression coefficients of women’s decision-making power and its square terms on food budget share were not significant (Table 1). Other significant variables included asset quintiles. The better off households were, the less budget was spent on food. Similarly, the better educated household heads and spouses were, the less budget was spent on food. The findings are consistent with the international literature that when households grow wealthier, and female and male heads of households are become better educated, the household expenditure is more likely to be diversified to other non-food items.

The regression analysis by rural and urban status (Table 2) showed the correlation between food budget share and women’s decision-making power was not significant after adjusting for other variables. The overall relationship between food budget share and women’s power was neither negative nor significant. But clearly the relationship was not positive in Pakistan’s case. This is different from the traditional view that women’s power is positively associated with expenditures on necessities, such as food. In fact, the literature contains different findings on this subject. For example, Hoddinott and Haddad (1995) found that in Cote D’Ivoire, women’s income was positively correlated with household necessities (such as food) but negatively with alcohol and cigarettes. However, Lancaster et al. (2006) suggested, from their empirical analysis in India, that budget shares and women’s decision-making power were U shaped instead of linear. Similarly, Maitra and Ray (2006) showed that, in South Africa, gender did not matter much for the purchase of food, clothing, and energy. The evidence from this paper shows weak or even no relationship between women’s decision-making power and food budget share.

Caloric and Nutrition Availability and Women’s Power

Although the results presented so far show no significant association between food budget shares and women’s power for the overall sample, this finding is not automatically linked to the relationship between women’s power and food quantity and quality, which are more relevant to human development. Women may spend more efficiently on food consumption, purchasing more nutritious foods with less money, for example. Some evaluations of conditional cash transfer programs showed that when women’s power increases, i.e., as cash transfers go directly to women, households consume more calories (Attanasio and Lechene 2002; Djebbari 2005) and more nutritious calories (Hoddinott and Skoufias 2004; Hou 2010). This paper used caloric availability and nutrition availability to examine the relationship.

Non-parametric Analysis

Figure 2 shows the relationship between women’s power and total caloric and nutrition availability after controlling for per capita expenditure. The non-parametric analysis showed that women’s decision-making power only seemed to have a positive correlation with a subset of nutrients in both rounds. Notably, when women’s power increased, per capita availability of calories and some nutrients (carbohydrates, protein, iron) actually decreased in both rounds, except in the second round the relationship between protein and women’s decision-making power was more concave. One explanation is that when women decide what to purchase, they might not be educated enough to know the sources and importance of micro-nutrients, but rather consider more the tastes and broad values of food sources.

In order to obtain a more intuitive explanation on nutrition availability and what households actually consumed, I further tested the relationship between women’s power and calories from grains, vegetables, fruits, and animal products (Fig. 3). The result showed that in the 2005–2006 round, calories from vegetables and fruits increased with higher women’s decision-making power; however, in the 2007–2008 round, the relationship became nonlinear and non-monotone. But overall, higher availability of vegetables and fruits was most likely associated with higher availability of vitamin C. In both rounds, higher women’s power was associated with lower caloric availability from grains (a major source of carbohydrates) and higher caloric availability from animal products (a major source of lipid).

Regression Analysis

After controlling for other variables, the regression analysis (Table 1) showed that the relationship between women’s decision-making power and nutrition did not have a clear and consistent pattern. In the case of lipid and vitamin C, the linear terms were positive and significant, but the square terms were negative—implying a concave relationship between lipid and vitamin C. The turning point for lipid and vitamin C was 0.529 and 0.61 respectively. That is, the lipid and vitamin C availability increased at a decreasing rate till when the women’s decision-making power reached to 0.529 or 0.61, respectively. The results from Table 3 showed that most of the increase of these nutrients came from more purchasing of vegetables and animal products. The linear coefficient for calories from vegetables was 0.132 and the coefficient for the square term was −0.0644. The turning point was 1.02, out of the range of 0–1 of the women’s decision-making power. This implies that calories from vegetables increased as women’s decision-making power increased. Similarly, the linear coefficient for calories from vegetables was 0.160 and the coefficient for the square term was −0.107. The turning point was 0.74, in the range of 0–1 of the women’s decision-making power. This implies that calories from animal started to increase as women’s decision-making power increased, but decreased when the women’s decision-making power reached around 0.74.

While the relationship between the lipid intake and animal products correspond to each other, the intake of vegetables increased with the women’s decision-making power, but intake of vitamin C decreased after women’s decision-making power reached 0.61. There was also no significant relationship between intake of protein and women’s decision-making power. There are two possible explanations. The first is the 58 food items and the conversion from these food items to micro-nutrients cannot fully capture the complete picture of the intake of micro-nutrients in the households. Second, most household wives in Pakistan have limited education and their knowledge about nutrition is limited. Their purchasing decisions largely rely on what is available in the market and their own tastes and preferences, rather than a pure nutritional perspective. A more elaborated survey is required to test whether either or both of these two hypotheses are true. Assuming that the second possible reason is the case, this implies that community-level education on nutrition targeted to women might increase their awareness on this subject, thus change their purchasing behaviors and ultimately improve household members’ nutrition and health.

The urban and rural analysis (Tables 2, 4) shows the relationship between women’s decision-making power and nutrition availability was slightly different between the rural and urban areas. In terms of total caloric and carbohydrate availability, the relationship was significant and convex for both dependent variables in urban areas; but there was no significant relationship in rural areas. However, there was a strong positive concave relationship between vitamin C’s availability and women’s decision-making power in both areas; and a similar relationship between lipid availability and women’s decision-making power but only in the rural areas. The exact reasons behind these observations are hard to identify, but the availability of food items from the market and home production might play some roles (Friedman et al. 2012). In rural areas where the main source of the food is from home production, women’s decision making matters less; rather, the availability from home production will determine the quantity and types of calories. In urban areas where the main source of food is from market, quantity and types of food purchased will depend on more factors including who directs what to buy. The findings from analysis on caloric availability from different sources (Table 4) suggests in rural area the relationship with women’s decision-making power was concave for calories from vegetables and animal products; in urban areas, the relationship with women’s decision-making power was convex for calories availability from grains and concave for calories availability from animal products. The general conclusion is that there was no evidence suggesting that women’s decision-making power was strongly associated with food budget share or nutrition in Pakistan.

Child School Enrollment and Women’s Power

In this section, I examined the relationship between women’s decision-making power and child school enrollment. It is commonly believed that school enrollment increases if women become more powerful in the household decision-making process. However, some recent literature has challenged this view. Specifically, Basu’s (2006) theoretical model asserted, “if the woman has more decision-making power than the man, [she] will garner a greater share of the income produced by child labor and actually benefit from child labor.” That non-linear prediction was further supported by some empirical evidence, including Felkey (2013) in Bulgaria, Lancaster et al. (2006) in three states of India, and Gitter and Barham (2008) in Nicaragua.

Non-parametric Analysis

Figure 4 clearly shows an upward linear relationship, in both rounds, between women’s decision-making power and child school enrollment for both girls and boys, independent of the welfare status of the children, measured by household per capita expenditure. Individual school enrollment is used in the diagram in order to more directly show the relationship between women’s decision making power and individual school enrollment. The finding is consistent with the classic views and the results of many empirical studies, including Schultz (1990) in Thailand, Thomas (1990) in Brazil, Binder (1999) and Adato et al. (2003) in Mexico.

Regression Analysis

In the regression analysis, the percentage of children who were enrolled in school out of the total number of children in that household was used as the dependent variable. Since it is a continuous variable between 0 and 1, regression analysis was applied to understand the relationship between child school enrollment and women’s decision making. Table 5 presents the results. Column (1) shows there was no relationship between children school enrollment and \(\uptheta_{\text{w}} \;{\text{or}}\; \uptheta_{\text{w}}^{2}\) However, the results differed for girls. Girls’ school enrollment linearly increased with \(\uptheta_{\text{w}}^{2}\) implying that when women have greater decision power, the girls were much more likely to be enrolled in school; the results on boys were not significant. As expected, the education of both household heads and spouses played significant roles. The higher their education levels were, the more likely children were to be enrolled in school.

Table 6 shows the analyses by rural and urban status. It is clear from the analyses that the strong positive relationship between women’s decision-making power and girl’s education is largely driven by rural girl’s school enrollment. In another words, women’s decision-making power matters a lot more for the school enrollment of rural girls.

Such gender-differentiated impacts are also consistent with the literature. For example, Thomas (1994) showed that Brazilian mothers’ non-wage income positively affected their daughters’ health but not their sons’. Duflo (2003) showed that in South Africa, the impacts of exogenous income transfers in the form of old-age pensions were more likely to increase health outcomes of granddaughters of grandmothers than any other grandparent–grandchild relation. This finding implies that women in Pakistan are more likely to invest in girls’ education, when they have more decision-making power, particularly in the rural area.

Robustness Check

In the earlier stage of the work, I used the eight questions in the PSLM to construct women’s decision-making power index. To check the robustness of the results, I also defined women’s decision-making as equal to 1 (instead of 0.5) if women made the decision jointly with their husbands. Most results are quite similar to the results presented here, and the main conclusion and policy relevance are the same. I particularly want to stress that the results on child education was quite robust to different women’s decision-making power indices constructed. This implies the importance of empowering the female heads of the households for the purpose of increasing households’ investment in children’s education.

Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg was used for testing heteroskedasticity (Breusch and Pagan 1979; Cook and Weisberg 1983). The test was not significant in the case when dependent variables were food budget share, total calories availability, lipid, calories from vegetables and fruits. However, the test was significant for other variables presented in Tables 1 and 3. I then used weighted least squares for robust estimation of those measures (Park 1966). The estimation results from weighted least square were consistent with the results from the OLS estimation showed in Tables 1 and 3 and are available upon request. The VIF test for multicollinearity was not significant for all regressions.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Few studies have examined women’s bargaining power and human development outcomes in cultures where men’s power dominates and women are often perceived to have limited impacts on household decisions. Using data from Pakistan, this paper found that in Pakistan, the relationship between women’s decision-making power and nutrition was not linear and varied depending on rural or urban residence. There was no clear evidence that higher women’s decision-making power would lead to better nutrition availability in Pakistan, but overall households were more likely to consume less grain and more vegetables. When women had higher decision-making power, children, particularly rural girls, were more likely to be enrolled in school.

The fact that women’s decision-making power is associated with girls’ school enrollment is important in policy design. As discussed in the introduction session, two hypotheses are involved in designing programs involving potentially shifting power distribution within the households and improving human development. First, women make better decisions with regards to children’s education and nutrition; and second, a larger income or asset share increases decision making of the women within households. This study tested the first assumption using the available data to understand the relationship between women’s decision-making power and some human development indicators, including child school enrollment.

Under the Benazir Income Support Program (World Bank 2009), the Government of Pakistan transfers Rs. 1000 per month to ever-married women in eligible poor households. The finding generally supports higher women’s decision-making power as associated with higher human development investment within the households, such as girls’ school enrollment. However, results on the relationship of women’s decision-making power and nutrition availability suggest that Pakistani women might not be adequately educated on nutrition. Even though they have power to make decisions on what to buy and what to eat, they might not be able to most efficiently allocate the resources from the nutritional aspect. Thus, giving cash alone to women might not maximize the potential effects on human development. The provision of necessary education/training on nutrition and health promotion is also an important factor in achieving the ultimate policy goals. Some international programs have successfully used community-based educational programs, such as Plásticas in the Mexican Opportunidades program, to guide mothers on how to better use additional income resources and how to better promote nutrition, hygiene, and health in general (Hoddinott and Skoufias 2004). Similar programs, if implemented successfully, should further help the Benazir Income Support Program beneficiaries in moving towards the achievement of the ultimate human development goals.

Notes

The male head of households were interviewed by a male enumerator separately.

If a husband makes the decision by himself, he is considered to have decision-making power equal to 1; if a husband “jointly makes the decision,” he is considered to have decision-making power equal to 0.5; if a husband was not involved at all in the decision making, he is considered to have decision-making power equal to 0.

The t test results are available upon request.

The slight U shape at the left tail is due to the outliers of log per capita expenditure.

Individual school enrollment is defined based on the question “Did… enroll in school /institution last year?” It is defined as 1 if the answer is “yes” and 0 if the answer is “no.”.

References

Adato, M., de la Briere, B., Mindek, D., & Quisumbing, A. R. (2003). The impact of PROGRESA on women’s status and intrahousehold relations. In A. R. Quisumbing (Ed.), Household decisions, gender, and development: A synthesis of recent research. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Allendorf, K. (2007). Do women’s land rights promote empowerment and child health in Nepal? World Development, 35(11), 1975–1988. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.12.005.

Amin, S. (1997). The poverty–purdah trap in rural Bangladesh: Implications for women’s roles in the family. Development and Change, 28(2), 213–233. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00041.

Attanasio, O., & Lechene, V. (2002). Tests of income pooling in household decisions. Review of Economic Dynamics, 5(4), 720–748. doi:10.1006/redy.2002.0191.

Basu, K. (2006). Gender and say: A model of household behaviour with endogenously determined balance of power. The Economic Journal, 116(511), 558–580. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01092.x.

Becker, G. S. (1981). Altruism in the family and selfishness in the market place. Economica, 48(189), 1–15. doi:10.2307/2552939.

Binder, M. (1999). Schooling indicators during Mexico’s “Lost decade”. Economics of Education Review, 18(2), 183–199. doi:10.1016/s0272-7757(98)00028-4.

Breusch, T. S., & Pagan, A. R. (1979). Simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica, 47(5), 1287–1294. doi:10.2307/1911963.

Cleveland, W. S. (1979). Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(368), 829–836. doi:10.1080/01621459.1979.10481038.

Cook, R. D., & Weisberg, S. (1983). Diagnostics for heteroscedasticity in regression. Biometrika, 70(1), 1–10. doi:10.1093/biomet/70.1.1.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555.

Doss, C. (2006). The effects of intrahousehold property ownership on expenditure patterns in Ghana. Journal of African Economies, 15(1), 149–180. doi:10.1093/jae/eji025.

Duflo, E. (2003). Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old age pensions and intrahousehold allocation in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review, 17(1), 1–25. doi:10.1093/wber/lhg013.

Felkey, A. J. (2013). Husbands, wives and the peculiar economics of household public goods. European Journal of Development Research, 25(3), 445–465. doi:10.1057/ejdr.2012.56.

Friedberg, L., & Webb, A. (2006). Determinants and consequences of bargaining power in households. NBER Working Paper 12367, National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w12367.

Friedman, J., Hong, S., & Hou, X. (2012). The impact of food crisis on consumption and caloric availability in Pakistan—evidence from cross-section and panel data. World Bank HNP Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Gitter, S. R., & Barham, B. L. (2008). Women’s power, conditional cash transfers, and schooling in Nicaragua. World Bank Economic Review, 22(2), 271–290. doi:10.1093/wber/lhn006.

Hakim, A., & Aziz, A. (1998). Socio-cultural, religious, and political aspects of the status of women in Pakistan. Pakistan Development Review, 37(4), 727–746.

Hallman, K. (2000). Mother-father resource control, marriage payments, and girl-boy health in rural Bangladesh. Food Consumption and Nutrition Division Discussion Paper, No. 93. Washington, DC: International Food Policy and Research Institute.

Hamid, S., Johansson, E., & Rubenson, B. (2009). “Who am I? Where am I?” Experiences of married young women in a slum in Islamabad, Pakistan. BMC Public Health, 9, 265. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-265.

Hamid, S., Johansson, E., & Rubenson, B. (2010). Security lies in obedience—Voices of young women of a slum in Pakistan. BMC Public Health, 10, 164. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-164.

Hoddinott, J., & Haddad, L. (1995). Does female income share influence household expenditures? Evidence from Côte d’ivoire. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 57(1), 77–96. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0084.1995.tb00028.x.

Hoddinott, J., & Skoufias, E. (2004). The impact of PROGRESA on food consumption. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53, 37–61. doi:10.1086/423252.

Hou, X. (2010). Challenges for youth employment in Pakistan: Are they youth-specific. Pakistan Development Review, 49(3), 193–212. doi:10.2307/41261044.

Hou, X. (2011). Women’s decision making power and human development: Evidence from Pakistan. In Policy research working paper series. RePEc:wbk:wbrwps:5830. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hou, X., & Ma, N. (2012). The effect of women’s decision-making power on maternal health services uptake: Evidence from Pakistan. Health Policy and Planning, 28(2), 176–184. doi:10.1093/heapol/czs042.

Lancaster, G., Maitra, P., & Ray, R. (2006). Endogenous intra-household balance of power and its impact on expenditure patterns: Evidence from India. Economica, 73(291), 435–460. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.2006.00502.x.

Maitra, P. (2004). Parental bargaining, health inputs and child mortality in India. Journal of health economics, 23(2), 259–291. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.09.002.

Maitra, P., & Ray, R. (2002). The joint estimation of child participation in schooling and employment: Comparative evidence from three continents. Oxford Development Studies, 30(1), 41–62. doi:10.1080/136008101200114895.

Maitra, P., & Ray, R. (2006). Household expenditure patterns and resource pooling: Evidence of changes in post-apartheid South Africa. Review of Economics of the Household, 4(4), 325–347. doi:10.1007/s11150-006-0011-6.

McElroy, M. B., & Horney, M. J. (1990). Nash-bargained household decisions. International Economic Review, 31(1), 237. doi:10.2307/2526642.

Menon, N., van der Meulen Rodgers, Y., & Nguyen, H. (2014). Women’s land rights and children’s human capital in Vietnam. World Development, 54, 18–31. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.07.005.

Park, R. E. (1966). Estimation with heteroscedastic error terms. Econometrica, 34, 888. doi:10.2307/1910108.

Quisumbing, A. R., & Maluccio, J. A. (2003). Resources at marriage and intrahousehold allocation: Evidence from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and South Africa. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 65(3), 283–327. doi:10.1111/1468-0084.t01-1-00052.

Schady, N., & Rosero, J. (2008). Are cash transfers made to women spent like other sources of income? Economics Letters, 101(3), 246–248. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2008.08.015.

Schultz, T. P. (1990). Testing the neoclassical model of family labor supply and fertility. Journal of Human Resources, 25(4), 599–634. doi:10.2307/145669.

Thomas, D. (1990). Intra-household resource allocation: An inferential approach. Journal of Human Resources, 25(4), 635–664. doi:10.2307/145670.

Thomas, D. (1994). Like father, like son: Like mother, like daughter. Journal of Human Resources, 29(4), 950–988. doi:10.2307/146131.

UNICEF. (2010). Pakistan statistics. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/pakistan_pakistan_statistics.html. Accessed 22 Dec 2014.

World Bank. (2009). International development association program document for a proposed social safety net development policy credit to the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

World Bank. (2014). Labor supply and vulnerability in Pakistan. Washington, DC: World Bank Report.

Yusof, S. A., & Duasa, J. (2010). Household decision-making and expenditure patterns of married men and women in Malaysia. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 31(3), 371–381. doi:10.1007/s10834-010-9200-9.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the invaluable comments provided by Dominique Van De Walle and Carolina Sanchez on the earlier version. This paper also greatly benefited from discussions with Mansoora Rashid, Songqing Jing, Andrea Vermehren, Iftikhar Malik, Cem Mete, Dhushyanth Raju, participants of the South Asia Human Development Knowledge Exchange Group Seminar, the Gender Action Plan Conference and all Pakistan Social Protection team members. I thank Ning Ma for her excellent assistance in preparing the data, Jing Zhang for helping with tables and invaluable comments received from two anonymous reviewers and the editor Professor Elizabeth Dolan. As usual, the findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. This work was supported by the Gender Action Plan Trust Fund and the Trust Fund for environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development (TFESSD) through the World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, X. How Does Women’s Decision-Making Power Affect Budget Share, Nutrition and Education in Pakistan?. J Fam Econ Iss 37, 115–131 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9439-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9439-2

Keywords

- Household bargaining

- Women’s decision making power

- Human development

- Education

- Nutrition

- Islamic culture

- Pakistan