Abstract

This study examined financial capability and economic hardship among low-income older Asian immigrants in a supported employment program (N = 142). Financial capability was defined as a combination of financial literacy, financial access, and financial functioning. Economic hardship was defined as the inability to meet basic needs. Results demonstrated that the majority of the sample had difficulty meeting basic needs. Most respondents answered basic financial knowledge questions incorrectly, and few applied prudent financial management skills. Results indicated that financial access and financial functioning were negatively associated with the risk of experiencing economic hardship, whereas financial literacy was not significantly associated. These findings call for active public policies and programs that address economic challenges among low-income Asian immigrants by enhancing their financial capability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Older immigrants are economically vulnerable. A substantial proportion of older immigrants live in poverty, despite higher participation rates in public assistance programs when compared to their native counterparts (Burr et al. 2008; Nam and Jung 2008). Lower income levels among older immigrants may be explained by the lower percentage of individuals with Social Security benefits and other sources of retirement income (e.g., pensions). About 70 % of older immigrants are covered by Social Security benefits compared to almost universal coverage among native older adults, and only 22 % of older immigrants have retirement income other than Social Security while 44 % of native older adults do (Borjas 2009).

Older Asian immigrants are no exception to these trends: The poverty rate is 14 % among older Chinese immigrants, 21 % among older Korean immigrants, and 24 % among older Vietnamese immigrants (Phua et al. 2007). This is contrary to public perception of the economically successful Asian American. High poverty rates among older Asian immigrants are a serious social and economic issue considering the rapid growth in this population. Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial group in the United States, with an estimated population growth rate of 46 % between 2000 and 2010, higher than Hispanics’ (43 %) (Asian Americans Advancing Justice 2011). Older Asian Americans also show rapid growth rates. The percentage of Asian Americans among older adults (65 years old or older) rose from 1.4 % in 1990 to 3.4 % in 2010. It is notable that nearly 75 % of Asian Americans are foreign-born (Pew Research Center 2012). The population of older Asian immigrants (age 65 and over) is expected to reach 7.5 million by 2050, 8.5 % of all older adults in the United States (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics 2012; He et al. 2005). The demographic trend of older Asian immigrants suggests that it is critical to address the economical vulnerability faced by this population.

In addition to a high poverty rate, older Asian immigrants tend to have low levels of financial capability, which may exacerbate their economic vulnerability. Financial capability—which can be conceptualized as a combination of financial knowledge, financial access, and financial functioning (Huang et al. 2013)—likely reduces the risk of economic hardship. Given the same amount of economic resources, individuals with high-level financial capability may develop financial strategies to prevent themselves from experiencing economic hardship; they are more likely to allocate their limited economic resources efficiently so that they can get by during times of economic difficulty.

Unfortunately, older immigrants—especially those who came to the United States during the later stages of their lives (old-age immigrants)—have little chance to obtain the financial knowledge and management skills that are essential for financial activities in America (Nam et al. 2013). A substantial portion of immigrants experience difficulty navigating mainstream financial institutions (e.g., banks, credit unions) as a result of language barriers and documentation requirements (Osili and Paulson 2008; Paulson et al. 2006).

High poverty rates and low levels of financial capability suggest that older immigrants are at high risk for economic hardship. Existing literature demonstrates older immigrants’ vulnerability with regard to economic hardship as indicated by high rates of food insecurity (Nam and Jung 2008); unmet consumption needs (Angel et al. 2003); and low rates of health insurance coverage (Choi 2011; Nam 2008) and health service use (Choi 2011; Wong et al. 2006).

Although existing literature provides invaluable information about economic hardship among older immigrants, our knowledge of this topic is limited, partly because no existing study tested the role of financial capability. Financial capability is crucial to understanding economic hardship in that it affects an individual’s ability to develop coping mechanisms when faced with economic challenges. To fill the gap in the literature, the present study examined the associations between financial capability and economic hardship among low-income older Asian immigrants with the use of survey data collected from participants in a supported employment program: the Senior Community Service Employment Program (SCSEP) operated by the National Asian Pacific Center on Aging (NAPCA). All participants of SCSEP were 55 years old or older and had income levels of <125 % of the federal poverty guideline. The findings of the study have important practice and policy implications to expand older Asian immigrants’ financial capability and improve their economic well-being.

Background

A Theoretical Framework of Financial Capability

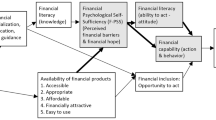

Financial capability is a concept that captures important elements that positively contribute to an individual’s financial well-being. Despite the frequent use of this term, there is no general consensus with regard to its definition (Birkenmaier and Huang 2013). This study adopted a theoretical framework of financial capability that is grounded in Nussbaum’s capability approach (Nussbaum 1999) and integrated three elements of financial capability: financial literacy, financial access, and financial functioning (Sherraden 2013; Birkenmaier and Huang 2013). Financial literacy is the understanding of financial concepts on multiple financial domains, such as personal finance (e.g., interest, investment risk), borrowing, saving, and protection (Huston 2010). Financial access is viewed as the availability of beneficial and appropriate financial products and services (Sherraden 2013; Huang et al. 2013). Financial functioning is defined by behaviors related to finances, such as budgeting, saving, making financial decisions, and other financial management. According to Nussbaum’s capability approach (1999), financial literacy is the internal capability and financial access is the external environment of an individual to achieve financial functioning. In other words, financial literacy is the ability to act, financial access offers the opportunity to act, and financial functioning is the application of financial literacy in a given external context as reflected by an individual’s financial behaviors and actions (e.g., financial management) (Sherraden 2013; Huang et al. 2013). These three elements of financial capability are included in the dashed box of Fig. 1, and their relationships are specified as well: Both financial literacy and financial access are positively related to financial functioning.

Financial Capability Among Older Immigrants

Relatively little is known about older immigrants’ financial capability. Previous research indicates that, in general, many older adults lack essential financial capability (Gillen and Kim 2013; Haron et al. 2013; Lusardi and Mitchell 2006; Nam et al. 2013). For example, in one study using data from the 2004 Health and Retirement Study, only a third of older adults gave correct answers to three basic financial questions about compound interest, inflation, and risk diversification (Lusardi and Mitchell 2006). The Rand American Life Panel demonstrated that financial illiteracy is even more acute among older women, racial minorities, and those who are the least educated (Lusardi and Mitchell 2007).

The literature also illustrates that immigrants have low levels of financial capability. Immigrants tend to have low levels of financial knowledge, especially those with low levels of education and limited English proficiency. Many immigrants come to the United States with no prior knowledge of the US financial system (Paulson et al. 2006). It is not surprising that even well-educated immigrants with English proficiency have a difficult time understanding the financial system and financial products of their new country, which may be much more complicated than and dramatically different from what was present in their countries of origin (Osili and Paulson 2006). A qualitative study illustrated that, as a result of their lack of understanding of financial systems (e.g., the role of credit history) and financial products (e.g., mortgage products), immigrants with limited income and a lesser degree of English proficiency had difficulty obtaining financial services unless community-based organizations (CBOs) provided financial guidance (Patraporn et al. 2010).

In terms of financial access, immigrants face the same barriers as disadvantaged native groups, including the high costs of banking services (e.g., high account maintenance fees), lack of credit history, and inconvenient locations and hours of banking operation (Joassart-Marcelli and Stephens 2010; Newberger et al. 2004; Rhine and Greene 2006). In addition, documentation requirements (e.g., Social Security numbers) tend to deter immigrants—especially undocumented immigrants—from opening bank accounts and applying for mortgages (Paulson et al. 2006). Immigrants with limited English proficiency have difficulty communicating with financial institutions due to a lack of interpretation and bilingual services. Inhospitable atmospheres and discriminatory treatment may further restrict immigrants’ access to financial services (Osili and Paulson 2008). Immigrants from countries with fragile financial infrastructures may distrust and avoid mainstream financial institutions (Paulson et al. 2006). As a result, immigrants’ use of mainstream financial services is less than that of their native counterparts. Empirical evidence involving data collected from nonelderly populations showed that the percentage of unbanked individuals (i.e., those without transaction bank accounts) is much higher among immigrants than among native-born individuals (Rhine and Greene 2006). Immigrants are instead more likely to use alternative financial services (e.g., check cashers), which impose higher fees than mainstream services and do not improve credit scores (Joassart-Marcelli and Stephens 2010; Paulson et al. 2006). A lack of financial knowledge and limited access to financial services can lead to undesirable financial functioning; this is reflected by poor financial management and the inappropriate use of financial products.

To the best of our knowledge, there has only been one empirical study of financial capability among older immigrants (Nam et al. 2013). With the use of survey data collected from low-income older immigrants from Asia, Nam et al. (2013) demonstrated that this population has low levels of financial knowledge. The average number of correct answers was one out of four when answering basic financial questions about compound interest, bank interest rates, credit scores, and credit card debt management. The findings of this study indicate that the lack of financial capability could be an important predictor of economic vulnerability among older Asian immigrants.

Economic Hardship and Older Immigrants

There is increased research interest in economic hardship as a measure of economic well-being (Beverly 2001; Ouellette et al. 2004). In addition to traditional, income-based measures (e.g., the federal poverty threshold), economic hardship has been defined as a family’s inability to meet basic economic needs (Heflin et al. 2009), such as food, housing, and medical services (Ashiabi and O’Neal 2007; Beverly 2001). Terms such as material hardship and financial hardship have been used interchangeably with economic hardship when discussing these issues. The consumption-based indicators of economic hardship, which are directly linked to the outcomes of in-kind public assistance programs, enable a multidimensional evaluation of economic well-being and provide important insights into the financial strains and challenges individuals face when trying to meet their basic needs (Ouellette et al. 2004).

Economic hardship varies in response to individual socioeconomic characteristics and household composition. Heflin et al. (2007) suggested that there are three mechanisms that may account for economic hardship: availability of resources, competing demands, and coping strategies. Limited economic resources bar individuals and households from obtaining materials that are needed for basic consumption. In addition, competing demands for restricted economic resources may force people to make tradeoffs among their different needs. Finally, given the same financial circumstances and competing consumption needs, those with better coping strategies may be able to manage their resources more effectively and thus lower their risk of material hardship. Individual coping strategies are likely associated with one’s financial capability: Individuals who have financial capability probably develop more effective coping strategies at the time of economic crises when compared to those who do not have such capability.

Although there is extensive literature that addresses economic hardship among different populations—such as welfare recipients (Danziger et al. 2000), women with disabilities (Huang et al. 2010; Parish et al. 2009), and children with disabilities (Parish et al. 2008)—only a limited number of studies have focused on the population of older adults. Studies of older adults’ economic hardship generally do not use consistent measures of that hardship and often are not conducted on nationally representative samples; exceptions include the household food insecurity rates estimated by the US Department of Agriculture and some studies that have used data from the Health and Retirement Study. It is estimated that in 2011 food insecurity rates for households with elderly members and for elderly people living alone were 8.4 and 8.8 %, respectively (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2012). With the use of the 1996 Health and Retirement Study data, Tucker-Seeley et al. (2009) reported that about 20 % of older adults experienced food or medical hardship. According to the 2004 Health and Retirement Study data, <5 % of individuals 65 years old or older were facing challenges of food insufficiency, but more than 40 % had difficulty meeting health care and housing needs (Alley et al. 2009). Among older adults, the prevalence of economic hardship as measured by the need to cut back on food or medications is about 10 %, according to data from the 2006 Health and Retirement Study (Levy 2009).

Even fewer studies have examined economic hardship among older immigrants. Older immigrants without US citizenship are much more likely to experience food insecurity than their native counterparts (17 vs. 10 %) (Nam and Jung 2008). Older immigrants, especially those without citizenship and those who recently came to the United States, are far less likely to have health insurance coverage than their native counterparts (Choi 2011; Nam 2008), which results in limited access to preventive and necessary medical care (Choi 2011; Wong et al. 2006).

Research Hypotheses

The current study hypothesizes that financial capability has a negative association with economic hardship, as described in Fig. 1. More specifically, the study hypothesizes that all three elements of financial capability—financial literacy, financial access, and financial functioning—are negative predictors of economic hardship. Financial capability may reduce the risk of economic hardship via optimal financial management and planning to increase available resources, to avoid competing demands, and to develop appropriate coping strategies for financial strain. For example, individuals with knowledge of financial protection and with access to financial services may take actions to accumulate emergency savings to prepare for negative income shocks (Babiarz and Robb 2013). Those with high financial functioning may apply their budgeting practices to manage any competing needs.

Method

Data and Sample

We used survey data collected from low-income older Asian immigrants who were enrolled in a supported employment program, NAPCA’s SCSEP. Funded by the US Department of Labor, SCSEP provides employment and training opportunities that promote self-sufficiency among low-income older adults while they are performing meaningful community services. NAPCA is currently operating SCSEP at nine sites in seven states, and most participants in the program are immigrants from Asia. For this study, surveys were conducted at three SCSEP sites: Los Angeles and Orange County in California and New York City in New York.

The survey questionnaire included 44 questions about economic hardship, financial capability, demographic and household characteristics, and immigration status. The questionnaire was first developed in English and then translated into Chinese and Korean. Each translated questionnaire was also back-translated into English to ensure the accuracy of the translation.

Because NAPCA’s SCSEP participants must attend quarterly meetings, the questionnaires were distributed to SCSEP participants during the March 2012 quarterly meeting. Bilingual survey administrators attended the meetings and explained the study; they also informed participants of their right to not participate and to answer questions. The Social and Behavioral Science Institutional Review Board at the University at Buffalo approved the study design (Study # 4759).

Of the 220 participants who attended the meetings at the three sites, 183 filled out the questionnaire (83 % response rate). From these 183 cases, 23 were deleted from the analysis sample because they did not meet sample selection criteria (e.g., Hispanic immigrants or US natives); an additional 18 cases were excluded because they were missing information related to independent variables used in the analyses (Table 1). Thus, the final sample size was 142.

Measures

Dependent Variables

Economic hardship was measured with five questions that asked respondents whether their families had enough money to afford the following items: housing; clothing; furniture or equipment; food; and medical care. There were four answer categories for each question: strongly agree (coded as 0), agree (1), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (3). A greater score indicates a higher level of economic hardship.

Independent Variables

The independent variables of this study were the three elements of financial capability: financial literacy, financial access, and financial functioning. Financial literacy was indicated by the respondents’ financial knowledge and their knowledge of social programs. The survey measured financial knowledge through four “true or false” questions (coded 1 for correct and 0 for incorrect) about compound interest, interest rates, credit card debt, and credit ratings (e.g., “All banks give you the same rate of interest on your savings accounts.”). To measure financial literacy, this study included respondents’ knowledge of social programs in addition to their financial knowledge, because it is essential for older adults to understand their eligibility for and the benefits of Social Security and Medicare when making long-term financial plans. For the majority of older adults, Social Security benefits are their major income source, and Medicare is their primary health insurance (Wan et al. 2005). Respondents’ understanding of social programs was evaluated with five dichotomous items (coded 1 for correct and 0 for incorrect) about Social Security and Medicare, such as program eligibility and benefits (e.g., “You can work and still receive Social Security benefits.”).

In most previous studies (e.g., Beck et al. 2007), financial access has generally been measured at the macro level [e.g., the number of automated teller machines (ATMs) per 100,000 individuals]. Such measures are not available for the current study; to maintain confidentiality, the survey questionnaire did not ask about the location of the respondent’s residence. Older Asian immigrants’ access to financial services was thus indicated by their comfort level with regard to receiving financial services from mainstream financial institutions and by their evaluation of mainstream financial institutions. We assumed that older Asian immigrants had higher comfort levels with and more positive evaluations of mainstream financial institutions if they had greater financial access. The survey had six questions about the respondent’s comfort level with formal financial services, such as opening an account, depositing and withdrawing money, and applying for credit cards. There were four answer categories for each question: very comfortable (coded as 3), comfortable (2), uncomfortable (1), and very uncomfortable (0). Seven survey items examined respondents’ evaluation of formal financial institutions, such as “I feel welcome at banks/credit unions” and “Banks/credit unions treat me with respect;” these questions also had four answer categories: strongly agree (coded as 3), agree (2), disagree (1), and strongly disagree (0). A higher comfort level and a better perception of formal financial institutions reflected a higher level of financial inclusion.

As an indicator of financial functioning, financial management was measured with five questions about the financial behaviors of respondents or their families (e.g., “I keep track of my spending.”). These financial management questions had three answer categories: often true (coded as 2), sometimes true (1), and rarely true (0). A higher score indicated a higher level of financial functioning.

Control Variables

We created demographic, human capital, household, immigration-related, and survey-related characteristics as control variables. Demographic variables included the respondent’s gender, age, ethnicity, and marital status. The gender variable was dichotomous and coded as 1 for female and 0 for male. The age variable had three categories: <65 years old; 65 years old or older; and missing value. Ethnicity had three groups as well: Chinese (including Taiwanese), Korean, and other (e.g., Asian Indians, Filipinos).

Human capital variables included education, English proficiency, and health status. The education variable indicated the respondent’s level of formal educational attainment: less than a high school diploma, a high school diploma, or a Bachelor’s degree or higher. The English proficiency variable indicated how well a respondent speaks English with four categories: not at all, not too well, somewhat well, and very well. We combined the first two categories into one group and the last two categories into the other. The health status variable was generated with respondents’ own ratings of their overall health condition (1 for those who reported excellent, very good, or good health and 0 for those with fair or poor health).

Household characteristics consisted of marital status, household size, and asset ownership. Marital status was a dichotomous variable and coded as 1 for currently married and 0 for other. Household size indicated the number of people in the respondent’s household with three categories: only one person (coded as 1); two people (2); and three or more people (3). We created four dichotomous indicators of access to credit and asset ownership (coded as 1 for yes and 0 for no): credit cards, checking accounts, long-term savings, and homeownership. The long-term savings indicator demonstrated whether the respondent or someone in his or her household owned a savings account; a money market account or a certificate of deposit (CDP); a retirement account; stocks or stock mutual funds; or corporate, municipal, government, or foreign bonds.

The survey also had two immigration-related variables. One was visa status at entry, which included three categories: immigration visa, including a spouse or fiancé visa to marry a US citizen; a work, student, or business investment visa; and other (e.g., a visitor or tourist visa, refugee or asylum status). The age at immigration variable divided the sample into old-age immigrants (i.e., respondents who immigrated to the United States when they were 55 years old or older) and young-age immigrants (i.e., those who came when they were <55 years old). A survey-related variable was the survey location; this variable had three categories: Los Angeles, Orange County, or New York City.

Analytical Approaches

We used structural equations modeling to examine the relationship between financial capability and economic hardship among old Asian immigrants. The structural equations modeling analysis followed three steps.

First, each dependent or independent variable was defined as a latent variable. A latent variable in structural equations modeling typically corresponds with a hypothetical construct that is not directly observed (e.g., financial literacy) and that has to be measured via multiple observed indicators (Kline 2011). We applied confirmatory factor analysis to generate a standard measurement model for each dependent or independent variable. Every indicator was loaded only on the latent variable that it intended to measure.

Second, given appropriate model-fit indices that resulted from each measurement model, all measurement models of dependent and independent variables were fitted simultaneously. Because all observed indicators in the study were categorical variables, we used WLSMV (the weighted least squares estimator with robust standard errors and mean and variance adjusted) for confirmatory factor analysis (Muthén and Muthén 2012).

Third, based on the results of the measurement models, a latent dependent variable of economic hardship was regressed on the latent variables of independent variables (financial capability measures) and control variables. Financial capability consisted of three types of measures: financial literacy (financial knowledge and knowledge of social programs), financial access (comfort level with financial services and evaluation of mainstream financial institutions), and financial functioning (financial management). In this third step, both measurement models of dependent and independent variables and the regression analysis were fitted simultaneously. The parameters of interest were the regression coefficients of the three elements of financial capability, which indicated the marginal effects of financial literacy, financial access, and financial functioning on economic hardship among low-income older Asian immigrants.

Although respondents with missing values for control variables (N = 18) were excluded from the final analytic sample, we kept respondents with missing values for dependent and independent variables in the final analysis sample. Because all of these indicators were endogenous variables in the measurement models, the missing information for these indicators was imputed with the use of the full information maximum likelihood method (Muthén et al. 1987; Wothke 1998).

Supplementary analyses were conducted to test the robustness of our findings. First, among observed indicators of dependent and independent variables, we only selected those with high validity (standardized factor loading >.45) to construct measurement models, and also removed control variables from analyses. Second, to avoid the potential multi-collinearity issue, we only included one dichotomous indicator of asset ownership—checking account ownership—in the analysis. In addition, we replaced the age at immigration variable with the number of years that respondents stayed in the United States. Results from these supplemental analyses do not differ substantively from those reported in this paper (Results of the supplemental analyses can be requested from the first author of the study).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics of low-income older Asian immigrants in the final sample (N = 142). About half of respondents took the survey at the Los Angeles site. More than half of respondents were women, and 46 % were 65 years old or older. Respondents were less likely to be old-age immigrants. The proportion of Chinese (including Taiwanese) immigrants was slightly lower than that of Korean immigrants (32 vs. 39 %). More than 80 % of respondents had a high school diploma or higher. More than 40 % of sample participants reported that they speak English well or very well, and about two-thirds of respondents were married and described themselves as being in good health. Most respondents in the sample entered the United States with an immigration visa. Less than 50 % had credit cards and long-term savings, and one in five owned a home.

Table 2 lists the descriptive statistics of the survey items that measured financial capability. The proportion of missing values for each indicator is presented in the last column. While the survey created different missing responses, including “Cannot Read,” “No Answer,” “Not Applicable,” and “Others,” the majority of missing values in the variables listed in Tables 2 and 3 were caused by the lack of answers in these questions among survey participants. In terms of financial literacy, the proportion of respondents who gave a correct answer was <40 % for any financial knowledge question. The lack of knowledge about credit card debt and credit ratings was even more salient: <20 % of respondents gave a correct answer. Although 70 % of the sample respondents were aware that they needed 10 years of work experience to be eligible for Social Security benefits, less than half provided correct answers to other questions about social programs. These results clearly demonstrate the lack of financial knowledge among low-income older Asian immigrants. In terms of financial access, a substantial minority (about 20 %) reported feeling “very uncomfortable” or “uncomfortable” receiving formal financial services, while the majority of respondents evaluated mainstream financial institutions highly; this was consistent with findings regarding their comfort level with financial services. However, when compared to other questions about the evaluation of formal financial institutions, a relatively lower proportion of respondents (40 %) indicated that mainstream financial institutions met their financial needs. To increase the financial access of older Asian immigrants, it is critical to understand what their financial needs are and why they feel uncomfortable receiving financial services. With regards to financial management, only about 10 % of participants reported that they “often” set financial goals, stuck to financial plans, and had 3 months’ worth of emergency savings.

Table 3 lists the descriptive statistics of the five indicators of economic hardship. As expected, low-income older Asian immigrants face great challenges in this area. About 50 to 60 % of respondents strongly disagree or disagree that they have enough money for their homes, furniture, and medical care, thereby indicating that they have difficulty meeting these needs.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results

Appropriate model fit indices were obtained with the first-step analysis which applied confirmatory factor analysis to generate a measurement model for each dependent or independent variable. The results of the second-step analysis, which integrated all measurement models of dependent and independent variables simultaneously, were consistent with those of the first-step analysis: All 32 indicators, except for one (knowledge of Medicare eligibility), had standardized factor loadings of more than .56. Overall, the second-step analysis obtained great model fit indices (χ2[df = 449] = 618.46, p < .001; CFI = .96; TLI = .96; root mean square error of approximation = .05 [90 % confidence intervals = .04, .06]). The results suggest that the variables listed in Tables 2 and 3 are valid and reliable indicators for the concepts that they intend to measure. (The full analysis results of these two measurement models are not reported here but are available from the first author upon request.)

Structural Equations Analysis Results

Model 1 from Table 4 was used to regress the latent variable of economic hardship on three elements of financial capability (i.e., financial literacy, financial access, and financial functioning) and other control variables (χ2[df = 1,100] = 1,196.60, p < .05; CFI = .96; TLI = .90; root mean square error of approximation = .03 [90 % confidence intervals = .01, .03]). Two measures of financial literacy—financial knowledge and knowledge of social programs—were not statistically significantly associated with economic hardship. The standardized regression coefficients of respondents’ comfort level with financial services and evaluation of formal financial institutions (i.e., two measures of financial access) had negative signs, but only the comfort level with financial services was statistically significant. After controlling for other variables in the analysis, one standard deviation increase in the measures of comfort level with financial services reduced the measure of economic hardship of low-income older Asian immigrants by 30 % of a standard deviations (p < .01). As expected, higher financial functioning was statistically significantly related to lower levels of economic hardship. Respondents with higher financial functioning as measured by their degree of financial management were less likely to experience economic hardship. When the measure of financial management increased by one standard deviation, respondents’ economic hardship was reduced by about 20 % of a standard deviations (p < .05).

The results of Model 1 do not support the hypothesis that financial literacy is negatively associated with economic hardship. The association between financial literacy and economic hardship may be mediated through financial functioning as measured by financial management. Thus, Model 2 regresses economic hardship on financial literacy only (in addition to other control variables). Two measures of financial literacy are still not statistically significantly associated with economic hardship.

Two control variables—good health and missing age category—had significantly negative associations with economic hardship in both models. Respondents with better health status may have lower levels of medical needs and therefore have a lower risk of economic hardship. However, it is not clear why respondents with missing values for their ages are also less likely to report economic hardship.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between financial capability and economic hardship among low-income older Asian immigrants in a supported employment program. For this study, financial capability was defined as a combination of financial literacy, financial access, and financial functioning. Analysis results from survey data collected from three sites of NAPCA’s SCSEP demonstrated that low-income older Asian immigrants have difficulties meeting their basic needs: Nearly two-thirds of respondents do not have enough money for food, housing, furniture, clothing, or medical care. This is not surprising, considering that low-income Asian immigrants have low levels of financial capability, particularly in the areas of financial knowledge and financial management. The percentages of respondents who gave a correct answer for all four basic financial knowledge questions was lower than 36 %, and only one-tenth indicated that they often set financial goals, stuck to financial plans, or had emergency savings.

Two out of three elements of financial capability were negatively associated with economic hardship, thereby suggesting that financial access and financial functioning reduce one’s risk of experiencing economic hardship; this was consistent with our hypotheses. These findings also suggest that two key strategies to the promotion of economic well-being among low-income older Asian immigrants are to expand their access to financial products and services and to enhance their financial functioning. However, we did not find evidence that financial literacy (the internal ability of financial capability) was associated with economic hardship in a statistically significant way. Having financial knowledge may not in itself influence one’s risk of experiencing economic hardship. The effect of financial literacy on economic well-being may depend on the external environment as indicated by financial access or on the individual’s financial planning and management practices as indicated by financial functioning.

Although this study expands the current understanding of older Asian immigrants’ financial capability and economic hardship, it has several limitations. First, the sample is not a probability sample and thus may not be representative of low-income older Asian immigrants. The sample consisted of NAPCA’s SCSEP participants, who are likely different from older Asian immigrants not served by community organizations. Data were collected at three project sites in areas with high proportions of Asian immigrants and with active Asian communities. Older Asian immigrants in these areas may find it easier to access community resources and financial services (e.g., ethnic banks) compared to immigrants who are living in isolated areas. Second, the sample size is relatively small, and the analyses in the study may lack statistical power. The small sample size does not allow the study to examine the relationship between financial capability and economic hardship by ethnic group. However, it is important to note that older Asian immigrants include multiple ethnic groups (e.g., Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indians, Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese), and the demographics of these groups are different on many measures (Kim et al. 2012). Third, a non-negligible proportion of respondents had missing values for multiple variables, which may raise the issue of selection bias into the analysis sample. In addition, fewer studies have examined the measures of financial access than those on financial literacy; the validity and reliability of the measures on financial access should be further evaluated in the future.

The findings of this study have several implications. A high percentage of respondents experienced economic hardship: They had difficulties in meeting even basic needs. This is in stark contrast to the image of Asians as a model minority and the public perception of economically successful Asian immigrants. It is critical to address the challenges faced by Asian immigrants and not to ignore the acute issues hidden under the myth of the model minority. Because the number of older immigrant adults—especially from Asian countries—is growing (He 2002; Walters and Trevelyan 2011), more attention needs to be paid to the long-term economic security issues of this population.

The economic vulnerability demonstrated by this study necessitates a call for active public policies that address economic difficulties among older Asian immigrants. It is recommended that financial education and financial planning services designed to improve the financial capability of this population be provided. Because financial knowledge itself does not have a significant association with economic hardship, it is important to develop financial education that will actually change older Asian immigrants’ financial decisions and behaviors (e.g., setting financial goals, accumulating emergency savings). It is also crucial to expand financial access among low-income older Asian immigrants. Our findings indicate that a respondent’s comfort level with financial institutions is a strong predictor of his or her economic hardship experience, which suggests that negative experiences with the US financial system may increase an immigrant’s risk of experiencing economic hardship. Financial institutions need to improve their business practices to increase financial access among this population. Bilingual services, the acceptance of alternative identification, reasonable fees, and fair treatment may improve older Asian immigrants’ perceptions of financial institutions.

It is also recommended that ethnic CBOs be consulted during the development and implementation of social policies and programs for this population, including financial education, financial planning services, and operation models for financial institutions. Ethnic CBOs are knowledgeable about ethnic culture and provide programs and services in immigrants’ native languages; this helps ethnic CBOs to build trusted relationships with older immigrants. Ethnic CBOs would be efficient coordinators and communicators working with both older Asian immigrants and the US financial system for the promotion of financial education and programs for this population (Government Accountability Office 2010).

References

Alley, D. E., Soldo, B. J., Pagán, J. A., McCabe, J., deBlois, M., Field, S. H., et al. (2009). Material resources and population health: Disadvantages in health care, housing, and food among adults over 50 years of age. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S3), S693–S701. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.161877.

Angel, R. J., Frisco, M., Angel, J. L., & Chiriboga, D. A. (2003). Financial strain and health among elderly Mexican-origin individuals. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(4), 536–551. doi:10.2307/1519798.

Ashiabi, G. S., & O’Neal, K. K. (2007). Is household food Insecurity predictive of health status in early adolescence?: A structural analysis using the 2002 NSAF data set. Californian Journal of Health Promotion, 5(4), 76–91.

Asian Americans Advancing Justice. (2011). A community of contrasts: Asian Americans in the United States: 2011. Washington, DC: Asian Americans Advancing Justice.

Babiarz, P., & Robb, C. A. (2013). Financial literacy and emergency saving. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, Online First.,. doi:10.1007/s10834-013-9369-9.

Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Martinez Peria, M. S. (2007). Reaching out: Access to and use of banking services across countries. Journal of Financial Economics, 85(1), 234–266. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.07.002.

Beverly, S. G. (2001). Measures of material hardship: Rationale and recommendations. Journal of Poverty, 5(1), 23–41. doi:10.1300/J134v05n01_02.

Birkenmaier, J., & Huang, J. (2013). A new framework for financial capability: An extension of nussbaum’s capability approach. St. Louis, MO: Saint Louis University School of Social Work.

Borjas, G. J. (2009). Economic well-being of the elderly immigrant population. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Burr, J. A., Gerst, K., Kwan, N., & Mutchler, J. E. (2008). Economic well-being and welfare program participation among older immigrants in the United States. Generations, 32(4), 53–60.

Choi, S. (2011). Longitudinal changes in access to health care by immigrant status among older adults: the importance of health insurance as a mediator. The Gerontologist, 51(2), 156–169. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq064.

Coleman-Jensen, A., Nord, M., Andrews, M., & Carlson, S. (2012). Household food security in the united states in 2011. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Danziger, S., Corcoran, M., Danziger, S., & Heflin, C. M. (2000). Work, income, and material hardship after welfare reform. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 34(1), 6–30. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2000.tb00081.x.

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. (2012). Older Americans 2012: Key indicators of well-being. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Gillen, M., & Kim, H. (2013). Older adults’ receipt of financial help: Does personality matter. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, Online First.,. doi:10.1007/s10834-013-9365-0.

Government Accountability Office. (2010). Consumer finance: Factors affecting the financial literacy of individuals with limited english proficiency. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

Haron, S. A., Sharpe, D. L., Abdel-Ghany, M., & Masud, J. (2013). Moving up the savings hierarchy: Examining savings motives of older Malay muslim. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34(3), 314–328. doi:10.1007/s10834-012-9333-0.

He, W. (2002). The older foreign-born population in the United States: 2000. Washington, DC: US Government Prining Office.

He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V. A., & DeBarros, K. A. (2005). 65+ in the United States:2005. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

Heflin, C. M., Corcoran, M. E., & Siefert, K. A. (2007). Work trajectories, income changes, and food insufficiency in a Michigan welfare population. Social Service Review, 81(1), 3–25. doi:10.1086/511162.

Heflin, C., Sandberg, J., & Rafail, P. (2009). The structure of material hardship in US households: An examination of the coherence behind common measures of well-being. Social Problems, 56(4), 746–764. doi:10.1525/sp.2009.56.4.746.

Huang, J., Guo, B., & Kim, Y. (2010). Food insecurity and disability: Do economic resources matter? Social Science Research, 39(1), 111–124. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.07.002.

Huang, J., Nam, Y., & Sherraden, M. S. (2013). Financial knowledge and Child Development Account policy: A test of financial capability. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 47(1), 1–26. doi:10.1111/joca.12000.

Huston, S. J. (2010). Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 296–316. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01170.x.

Joassart-Marcelli, P., & Stephens, P. (2010). Immigrant banking and financial exclusion in Greater Boston. Journal of Economic Geography, 10(6), 883–912. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbp052.

Kim, J., Chatterjee, S., & Cho, S. H. (2012). Asset ownership of new Asian immigrants in the United States. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(2), 215–226. doi:10.1007/s10834-012-9317-0.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

Levy, H. (2009). Income, material hardship, and the use of public programs among the elderly. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Retirement Research Center, University of Michgan.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2006). Financial literacy and planning: Implications for retirement wellbeing. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College, Department of Economics.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2007). Financial literacy and retirement planning: New evidence from the Rand American Life Panel. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Retirement Research Center, University of Michgan.

Muthén, B., Kaplan, D., & Hollis, M. (1987). On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika, 52(3), 431–462. doi:10.1007/BF02294365.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (2012). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén.

Nam, Y. (2008). Welfare reform and older immigrants’ health insurance coverage. American Journal of Public Health, 98(11), 2029–2034. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.120675.

Nam, Y., & Jung, H. J. (2008). Welfare reform and older immigrants: Food stamp program participation and food insecurity. The Gerontologist, 48(1), 42–50. doi:10.1093/geront/48.1.42.

Nam, Y., Lee, E. J., Huang, J., & Kim, J. (2013). Financial capability and asset ownership among low-income older Asian immigrants. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Newberger, R., Rhine, S., & Chiu, S. (2004). Immigrant financial market participation: Defining the research questions. Chicago Fed Letter, 199. Retrieved November 13, 2013, from http://www.chicagofed.org/digital_assets/publications/chicago_fed_letter/2004/cflfebruary2004_199.pdf.

Nussbaum, M. (1999). Women and human development: The capabilities approach. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Osili, U. O., & Paulson, A. (2006). Immigrant-native differences in financial market participation. Chicago: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Osili, U. O., & Paulson, A. L. (2008). Institutions and financial development: Evidence from international migrants in the United States. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3), 498–517. doi:10.1162/rest.90.3.498.

Ouellette, T., Burstein, N., Long, D., & Beecroft, E. (2004). Measures of material hardship: Final report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Parish, S. L., Rose, R. A., & Andrews, M. E. (2009). Income poverty and material hardship among US women with disabilities. Social Service Review, 83(1), 33–52. doi:10.1086/598755.

Parish, S. L., Rose, R. A., Grinstein-Weiss, M., Richman, E. L., & Andrews, M. E. (2008). Material hardship in US families raising children with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 75(1), 71–92.

Patraporn, R. V., Pfeiffer, D., & Ong, P. (2010). Building bridges to the middle class: The role of community-based organizations in Asian American wealth accumulation. Economic Development Quarterly, 24(3), 288–303. doi:10.1177/0891242410366441.

Paulson, A., Singer, A., Newberger, R., & Smith, J. (2006). Financial access for immigrants: Lessons from diverse perspectives. Chicago: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and the Brookings Institution.

Pew Research Center. (2012). The rise of Asian Americans. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Phua, V., McNally, J. W., & Park, K. S. (2007). Poverty among elderly Asian Americans in the twenty-first century. Journal of poverty, 11(2), 73–92. doi:10.1300/J134v11n02_04.

Rhine, S. L., & Greene, W. H. (2006). The determinants of being unbanked for US immigrants. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 40(1), 21–40. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00044.x.

Sherraden, M. (2013). Building blocks of financial capability. In J. Birkenmaier, M. Sherraden, & J. Curley (Eds.), Financial capability and asset development: Research, education (pp. 1–73). New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tucker-Seeley, R. D., Li, Y., Subramanian, S. V., & Sorensen, G. (2009). Financial hardship and mortality among older adults using the 1996–2004 Health and Retirement Study. Annals of Epidemiology, 19(12), 850–857. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.08.003.

Walters, N. P., & Trevelyan, E. N. (2011). The newly arrived foreign-born population of the United States: 2010 American Community Survey briefs. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

Wan, H., Sengpta, M., Velkoff, V. A., & DeBarros, K. A. (2005). 65+ in the United States: 2005. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

Wong, R., Díaz, J. J., & Higgins, M. (2006). Health care use among elderly Mexicans in the United States and Mexico: The role of health insurance. Research on Aging, 28(3), 393–408. doi:10.1177/0164027505285922.

Wothke, W. (1998). Longitudinal and multi-group modeling with missing data. In T. D. Little, K. U. Schnabel, & J. B. Mahwah (Eds.), Modeling longitudinal and multiple group data: Practical issues, applied approaches and specific examples (pp. 197–216). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grants from the Les Brun Research Endowment Fund, Buffalo Center for Social Research, School of Social Work, University at Buffalo, and the Civic Engagement Research Dissemination Fellowship Program, University at Buffalo. We are thankful to Christine Takada, Miriam Suen, Helen Jang, Norman Lee, Junghee Han, Xiao-yu Yang, Kerry Situ, and Yong-Jin Ahn for their assistance for data collection. We are grateful to Ya-Ling Chen, Elizabeth Hole, Jun Pyo Kim, Amanda Brower, and Sarah Nesbitt for their research assistance and to Jennifer Gann for editing assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, J., Nam, Y. & Lee, E.J. Financial Capability and Economic Hardship Among Low-Income Older Asian Immigrants in a Supported Employment Program. J Fam Econ Iss 36, 239–250 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9398-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9398-z