Abstract

This paper examined the labor supply and fertility effects of fertility incentives by making use of two major policy changes that occurred in Canada over the past 25 years: the Quebec Parental Insurance Program which provided generous parental leave benefits, and the series of cash-transfer fertility incentives introduced in Quebec in the 1980s. The empirical work for these projects was conducted using confidential versions of the Canadian Census and the Labour Force Surveys on-site at Statistics Canada. I found that while increases in the generosity of parental leave benefits substantially increased the birth rate and induced increases in labor supply among women of childbearing age, cash-transfer fertility incentives only slightly increased birth rates and decreased female labor supply. The net government cost of each additional birth due to an increase in the generosity of parental leave programs was $15,828 in 2008 Canadian dollars, whereas the net government cost of an additional birth due to cash-transfer fertility incentives was $223,625 in 2008 Canadian dollars. Therefore, paid parental leave is a low-cost way to increase fertility whereas the price per additional birth due to cash-transfer fertility incentives is quite high.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As fertility control has become quite reliable, having children has become more of an economic decision. Since having a child is an irreversible decision and children are very time and resource intensive, the trade-offs between family and career are hard to ignore. The ability to control fertility through effective oral contraceptives increased women’s career investments and labor force participation, delayed marriage, and decreased fertility expectations (Goldin and Katz 2002; Bailey 2006). Fertility rates have fallen to below replacement rates in many developed countries (Bongaarts 2002). Low fertility rates have raised concerns about aging populations and the viability of social security systems. In response to these concerns, various governments, including the national governments of Singapore, Germany, Poland, and Italy, have introduced pronatalist policies intended to raise the birth rate. Some of these benefits have been sizeable. For example, Singapore’s Working Mother’s Child Relief provided a maximum annual transfer of S$50,000 per child in 2009 (Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore 2009) and January 1, 2007 Germany increased the maximum monthly payment of eltengeld, which was paid to stay-at-home payment of infants, from € 450 to € 1800 (Kulish 2007). Beyond potentially expanding the next generation’s workforce through encouraging fertility, fertility incentives may also impact the labor supply of the current generation of women of childbearing age. The effects of fertility incentives on labor supply bring into play two classical problems in labor economics: the effect of social programs on labor supply and the effect of fertility on labor supply. These programs have taken on two major flavors: cash-transfer fertility incentives and parental leave benefits. The implementation of these programs raises three intuitive questions:

-

1.

To what extent do fertility incentives increase the birth rate?

-

2.

What are the effects of fertility incentives on labor supply?

-

3.

Net of labor supply, what is the cost per additional birth generated by fertility incentives?

This paper considered two natural experiments that occurred in Canada in the last three decades, and evaluated fertility incentives with regards to their effects on birth rates and female labor supply. I found that cash-transfer fertility incentives had small positive effects on the birth rate and were associated with decreases in labor supply while increases in the generosity of parental leave benefits both increased birth rates substantially and also increased labor supply. Specifically, the pronatalist policies introduced in Quebec in the late 1980s, including the Allowance for Newborn Children, which provided a baby bonus, and the Availability Allowance, which made annual payments to families with children five years old and younger, provided an opportunity to study the effect of cash-transfer fertility incentives as similar programs were not implemented in the other Canadian provinces and territories at the same time. Using data from the 1986, 1991, and 1996 Canadian Census 20 % Master Files I found that the program was associated with a 1.72 % increase in the birth rate and a decrease in labor force participation of approximately 4 percentage points among women who had a child age five or under. This corresponds to an 0.8 percentage point decline in labor force participation of women of childbearing age and a decline in earnings of C$403 per year in 1986 dollars. In contrast, when I evaluated the Quebec Parental Insurance Program (QPIP), which was introduced by the provincial government of Quebec in January 2006 and increased the benefit level of maternity leave benefits from the federal level of 55 % of previous income to 70 % of previous income for the first 25 weeks from takeup and also increased the cutoff for maximum insurable earnings, the results were starkly different. Using data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) Master Files, I found that the implementation of the program was accompanied by a 23.53 % increase in the birth rate as well as a 1.5 percentage point increase in the labor force participation rate of women age 25–45. Among women with infants there was an increase in leave-taking from work of about 5.4 percentage points.

Review of Literature

The irreversibility of the fertility decision and the fact that children are parental time-intensive makes the demand for births and the effects of additional births different from the case of the typical good in the consumer problem. When it offers a fertility incentive, a government clearly has an interest in the quantity and quality of children produced as a consequence of the program. However, it has very little influence over how the transfer money is spent. Not only are transfers received by inframarginal families that would have the same number of children without the subsidy, but within a family transfers may not be entirely directed towards the wellbeing of children. In particular, if adult family members consume more leisure because of the transfers, this will drive up the cost of the program by reducing the tax base.

The most straightforward question to ask about fertility incentives is to what extent they increase fertility. In the very short run, the timing of births might be adjusted through scheduled caesareans and inductions in order to receive benefits. Dickert-Conlin and Chandra (1999) found that the US personal exemption for dependent children and standard deduction for heads of household caused mothers to shift their delivery dates from January to December. Gans and Leigh (2009) found that the announcement of the AU$3000 Australian Maternity Payment in 2004 led pregnant women to shift their delivery dates to after the introduction date of the program. Similarly, Whittington et al. (1990) found that the American federal personal exemption for dependent children led to a positive and significant effect on the birth rate. Parent and Wang (2007) found that, while the 1970s reform of family allowances in Canada led to short run increases in births, these effects appeared to be tempo effects, so the reforms did not affect the total number of children born to women in the long run. Considering the longer term effects of cash-transfer fertility incentives on birth rates, Milligan (2005) attributed a 12 % increase in fertility in Quebec to the Allowance for Newborn Children, while Kim found that this program had little permanent impact on fertility and that the impact was largest for women with lower income (Kim 2012, 2014). The analysis of cash transfer fertility incentives in this article differs from Milligan’s and Kim’s work because it considered labor market outcomes in addition to fertility incentives, used the Canadian Census Master Files instead of the public microdata files so that age and parity of children are precisely constructed, and took account of other cash-transfer programs for families with dependent children that were concurrently introduced in Quebec, such as the Availability Allowance, in the cost-benefit analysis.

Fertility has been shown to respond to other public policies that are tied to the number and ages of children in a household. Baughman and Dickert-Conlin (2003) found that increases in the generosity of the American Earned Income Tax Credit led to an increase in births among both married and unmarried non-white women and an insignificant effect among white women. Using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979, Rosenzweig (1999) found that higher Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC) and lower marital prospects increased the probability of having a birth out of wedlock, while Hoffman and Foster (2000) found that a 25 % increase in AFDC benefits implied a 5 % increase in nonmarital births using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Also, Lundberg and Plotnick (1995) found that welfare guarantees increased premarital births among white adolescents, and Grogger and Bronars (2001) found that higher welfare payments prolonged the time between a woman’s first birth and marriage for unwed whites and a moderate link between base welfare benefits and subsequent fertility of unwed blacks. Using an experiment in the early 2000s in New Jersey that denied US$102 per month of benefits to recipients who conceived and gave birth to a second child while on welfare and US$64 per month for higher parity children, Jagannathan et al. (2004) found that lowered benefits reduce birth rates and that this effect was larger for groups who received benefits for less time.

The effect of fertility incentives on labor supply might depend on the magnitude of the fertility response as well as policy design. One of the most common ways to encourage childbearing while taking career considerations into account is through job-protected parental leave, which legally mandates that a parent’s employer preserve her job while she is on leave. These policies have taken on different forms, varying in the duration of leave offered, eligibility criteria, and the generosity of benefits payments during period of leave.

Most of the previous research on the effects of parental leave focused on the existence of parental leave and not on its characteristics. One of the most broadly studied programs was the American 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), which mandated 12 weeks of unpaid maternity leave. When considering general equilibrium effects, Gruber (1994) found that the group-specific mandate reduced the hourly wages of married women of childbearing age, which was the group most at risk of taking unpaid leave and thus the most likely to impose costs on employers. With respect to the impact of FMLA on mothers, Klerman and Leibowitz (1994) found that the introduction of the program increased the employment rates and the rates of being on leave of mothers of children less than 1 year old relative to those with children who were 2 or 3 years old. Using a comparison group of all other women, Baum (2003) found that the FMLA did not have a significant effect on the labor supply or wages of mothers with infants or women of childbearing age. In contrast, Waldfogel (1998) found that maternity leave had a positive effect on the wages of returning mothers and increased the probability that they returned to the same employer. In a separate study Waldfogel (1997) found that those who were formally covered by maternity leave had the steepest rate of wage growth.

The FMLA did not provide any income replacement, so its effects may be substantially different from programs that provide paid benefits. Understanding the effects of the different components of paid maternity leave benefits is of clear public policy interest. In a cross-country analysis of developed nations Ruhm (1988) found that countries with paid maternity leave had higher female employment to population ratios, but did not establish causality. Waldfogel (1988) argued that negative effects of mandated paid benefits may be counteracted by positive employment effects. Her argument was based on the fact that the United States, which had no paid parental leave, had a larger pay gap between women with and without children than the United Kingdom, which provided some income replacement during mandated parental leave. In defense of maternity benefits being productive, Ruhm and Teague (1997) found that, while unpaid maternity leave had no effects on GDP, paid leave was associated with an increase in GDP. Turning attention to the study of specific programs, Phipps (2000) found that the 1997 increase the minimum number of hours worked required to qualify for parental leave benefits in the year prior to takeup from 20 weeks with 15 h worked per week (300 h total) to 700 h over the course of year did not cause women in Canada to adjust their labor supply. Considering the effects of an increase in the duration of maternity benefits in Canada in 2001 Baker and Milligan (2008) found that an extension of the duration led to an increase in time away from work of mothers with infants. The effect of parental leave policies tend to effect mothers’ labor supply more than fathers’ labor supply. For example, in studies using Norwegian administrative data, Lappegard (2012) found that in a gender egalitarian parental leave scheme, mothers still took the majority of parental leave and Ugreninov (2013) found that paternity leave did not have a significant effect on mothers’ sick leave absences.

The effects of cash-transfer fertility incentives on labor supply have been less widely studied. Some of the most salient research has studied welfare benefits whose generosity depends on family structure. Since these programs are means-tested and often also have labor supply restrictions, they have a direct impact on the labor supply of people who are eligible. Livermore and Powers (2006) found that nutrition, employment, and instrumental social support programs were associated with higher employment among single mothers, while other social programs may have provided a disincentive to participating in the labor force. The American Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) has been one of the most widely studied such programs and requires that participants work in order to receive benefits. Not surprisingly, various authors, including Eissa and Liebman (1996), Meyer (2002), and Meyer and Rosenbaum (2001) found that the expansion of the benefit amount encouraged labor supply. However, most of the change occurred along the extensive margin and, at the higher eligible income levels, where benefits are being phased out, there seemed to be no adjustment in hours worked. Also, Cancian and Levinson (2006) considered the Wisconsin EITC supplemental benefit for families with three children and found that it had no significant effect on labor supply. Milligan and Stabile (2007) examined the case of the 1998 Canadian National Child Benefit which was integrated with social assistance payments in a subset of the provinces, and found that the integration of the benefit effectively lowered the welfare wall and led to a decrease in social assistance receipt.

Materials and Methods

Policy Variation

Figure 1, which was constructed using Statistics Canada’s series of live births (Statistics Canada 2013a, b), plots the number of births in Quebec and Canada. Panel A shows the number of births for all women from 1971 to 2011 and Panel B shows the number of births for women age 25–44 from 1991 to 2011. Note that in both graphs the trends of crude birth rate are roughly parallel. Over this period, the total fertility rates in Quebec lagged behind those in the rest of Canada and are well below the North American replacement total fertility rate of 2.085 (Espenshade et al. 2003). To counteract these trends, the government of Quebec introduced a series of policies designed to encourage childbearing in the late 1980s. These programs were mostly not income tested and applied to all parents of young children. This situation provided an appropriate policy environment to study the effects of cash-transfer fertility incentives on labor supply because similar programs were not introduced in the rest of Canada at the time. The programs in Quebec tended to favor higher parity children and, through a combination of allowances and tax exemptions, provided large subsidies to families with dependent children. This series of programs ended in 1997, due to the perceived ineffectiveness of the programs. In 2006, a second set of Quebec-specific fertility incentives was introduced: The QPIP effectively increased the income replacement rate of parental leave benefits.

Cash-Transfer Fertility Incentives

Figure 2 presents a timeline of the Quebec policy changes, and Table 1 summarizes the benefits for families earning C$40,000. The largest expansion of pronatalist policy was announced in the 1988 Quebec Budget Speech (Levesque 1988). These new policies included introducing of the Allowance for Newborn Children, which provided cash payments at birth; making the Availability Allowance, which provided payments to parents of children five and under, universal; and the eliminating the recovery of family allowances. Another major change occurred in 1986 when tax exemptions for dependent children were introduced. One of the key features of the programs implemented between 1988 and 1997 was that they were more generous for children of third or higher birth order and increased in generosity over time, as shown in Table 2 for the Allowance for Newborn Children. While payments for first and second parity children were either C$500 or C$1000 total for most of the life of the program, benefits for third or higher parity children increased from a total of C$3000 in 1988 to C$8000 at the end of the program.

In addition to these universal programs, Quebec also separated the Availability Allowance from the tax deduction for childcare expenses, further increasing transfers to families. The government of Quebec also introduced a home ownership program that provided government backed guaranteed loans for families with dependent children to purchase a first home. For low income families, Quebec revised its welfare program to take into the account the costs of childcare and also provided tax relief to families. These programs were eliminated with the replacement of the Act Respecting Family Assistance Allowances with the Act Respecting Family Benefits on September 1, 1997 (Québec 1997). The policies implemented by this legislation included the introduction of five Canadian dollar per day childcare. Details of these policy changes are available upon request.

Table 1 describes the benefits received by families of different compositions from the Allowance for Newborn Children, the Availability Allowance, family allowances, and tax exemptions for dependent children. The hypothetical families have taxable income of C$40,000 and their benefit levels are calculated for 1986, 1991, and 1996. Since most of the universal child-benefit programs in provinces outside of Quebec were administered through the income tax system and all provinces but Quebec were part of a federal-provincial tax agreement that made provincial income taxes proportional to federal income taxes, I took Ontario’s benefit levels to be representative of benefits in the rest of Canada. Panel A of Table 1 describes the 1 year benefits received by the constructed families while Panel B describes the total benefits that the family would have received for the existing children given the policy environment of that year through the age of 17, with an annual discount factor of 0.95. The constructed families have either zero children, one child age three, or two children age three and seven. Column 1 calculates the benefit level for each family in Quebec and Column 2 calculates the benefit level for each family in Ontario. Column 3 takes the difference between Column 1 and 2, which is the difference in benefits for a particular family composition in Quebec versus Ontario. Column 4 takes the difference between a given year’s value in Column 3 and the corresponding value for 1986. This number is the amount by which benefit increases since 1986 in Quebec exceed benefit increases in Ontario. Columns 5 through 8 repeat the exercise, adding an infant to each hypothetical family. Columns 9 through 12 consider the gains from having this additional child.

The most salient feature of Table 1 is that the gains in Quebec over the gains in Ontario relative to the 1986 benefit levels in Columns 4, 8, and 12 are positive in both panels. The positive values in Columns 4 and 8 show that all families with young children, regardless of whether or not they changed their fertility, would have received higher transfers in 1991 and 1996 than they would have under the programs in place in 1986. The positive values in Column 12 show that the increase in benefits for having an additional child compared to the benefit levels in 1986 was larger in Quebec than in Ontario. Interestingly, from Panel A it is clear that while the one year gain in benefits for having an additional child in Quebec relative to the rest of Canada was growing between 1991 and 1996 for third or higher parity children, it was actually declining for first and second parity children. Similarly, the present discounted value of the increase in lifetime benefits in Quebec from having an additional child relative to the benefits gain in Ontario in Column 12 of Panel B are increased from C$15,692 to C$19,779 between 1991 and 1996 for third parity children. For second parity children this barely changed; in 1991 the relative benefit gain is C$10,297 while in 1996 it is C$10,278. For first parity children, however, this gain declined, from C$6,208 in 1991 to C$4,809 in 1996.

One of the key features of cash-based fertility incentives is that they provide benefits to families who do not necessarily adjust their fertility because of the program. Columns 4 and 8 capture this effect. Comparing the lifetime benefits gains in Quebec versus Ontario in Columns 4 and 8 in Panel B it is clear that they were increasing in the parity of the child. For example, a family that has a first parity infant Quebec in 1996 could have expected a lifetime gain in benefits versus 1986 C$4,809 larger than the same family residing in Ontario. In comparison, a family that had a second parity child could have expected a relative lifetime gain of C$12,066 and a third parity child could expect a relative lifetime gain of C$26,818. Gains for infants were substantially larger than gains for older children. This occurred as a consequence of the Allowance for Newborn Children as well as the generosity of the Availability Allowance increasing in the parity of a child.

Quebec Parental Insurance Program

Prior to 2006 parental benefits in all Canadian provinces were administered at the federal level as prescribed by the Employment Insurance Act of 1996 and its amendments in 2000. Under the act major attached claimants, defined as those with at least 700 h of insurable earnings over the past year, could receive up to 15 weeks of pregnancy benefits and 10 weeks to care for a newborn infant, to be split between parents, at a 55 % replacement rate up to a cap of C$39,000 average annual earnings (Canada 1996). In 2000 the federal Employment Insurance Act was modified to extend the number of weeks of benefits for caring for a newborn from 10 to 35 to be shared between parents, leading to a total of 50 insured weeks. Furthermore, the definition of a major attachment claimant was redefined as one who has at least 600 h of insurable earnings over the past year (Canada 2000).

Starting January 1, 2006 benefits in Quebec have been administered by the provincial government under the QPIP. Footnote 1 This program increased income replacement rates, increased maximum insurable earnings, extended benefits to the self-employed, and introduced 7 weeks of designated paternity leave. The replacement rate was increased to 70 % for the first 18 weeks of maternity benefits, the 5 weeks of paternity benefits, and the first 7 weeks of parental benefits. For the remaining 25 weeks of parental benefits, the replacement rate remained 55 %. Maximum insurable earnings were also increased to C$60,500 from their previous level of C$39,000. Families also had the option to choose a special plan equal to 75 % of average weekly earnings, shortening the duration of benefits to 15 weeks for maternity leave, 3 weeks for paternity benefits, and 25 weeks for parental benefits. A minimum of C$2000 of annual earnings was required to qualify with no accompanying hours requirement. Average weekly earnings were calculated as the average of earnings in the 26 weeks prior to takeup. If less than 26 weeks were worked, then the average was the individual’s earnings over the 26 weeks prior to takeup divided by the larger of the number of weeks worked or 16. Also, maximum annual insurable earnings in Quebec were increased to C$60,500. Table 3 compares the design of the QPIP to the federal program. Under the federal program the maximum total benefit was C$21,750 while under the Quebec program the maximum total benefit was C$40,340.29. These benefits are financed by a payroll tax which was levied at a rate of 0.416 % on employees and 0.583 % on employers in 2006 and 2007 which was increased to 0.450 % on employees and 0.630 % on employers in 2008 (Québec 2007, 2008, 2009).

Empirical Strategy

The evaluation of each set of fertility incentives followed parallel difference-in-difference (DID) strategies. To understand the effects of the programs, I considered the effects of the policy changes on women of childbearing age who are exposed to the programs and the effects of the policy changes on women who are eligible for the program. In practice, I considered women age 25–45 to be of childbearing age. In the case of the cash-transfer fertility incentives, the group eligible was women with children age five or under, and when I considered parental leave benefits, the group eligible was either women who were pregnant or women who had children less than 1 year old. The effect on women who were eligible captured changes in takeup rates, and when considering the effects of parental leave on pregnant women, whether they engaged in strategic behavior to increase their benefit amounts. The average effect of the programs on women of childbearing age took into account these effects, as well as any effect the program may have had on women who adjusted their labor supply in anticipation of potential future benefits. Furthermore, an estimate of the effect of the program on the earnings of women of childbearing age makes it possible to calculate the extent to which tax revenues are affected by the programs.

Since the generosity of pronatalist benefits were increased only in Quebec, the other Canadian provinces serve as a control group. Consider the effect of the introduction of a program on the average woman of childbearing age. In Eq. 1, let \(y_{i}\) be the outcome variable of interest, \(Quebec_{i}\) be an indicator for residing in Quebec, let \( post_{i}\) be an indicator for the period after the program has been implemented, let \(Quebec_{i}\times post_{i}\) be the interaction of the two indicators, and let \(X_{i}\) be a vector of demographic characteristics. Assuming that, absent intervention, the change in the outcome variable \(y\) over time in Quebec and the rest of Canada would occur at the same rate, \( \beta _{3}\) identifies the effect of the program.

The assumption that the growth rate of \(y\) is the same in Quebec as it is in the rest of Canada can be relaxed by finding a group in geographic areas that was not directly affected by the policy change. Since the effect of maternity leave benefits on the labor supply of men and of women who were beyond childbearing age were second order, either group could serve as a valid control group. Let \(treated_{i}\) be a dummy for being in the treated group. Depending on the context, the treated group is either all women or childbearing age or the group of women who would have been eligible to receive the benefits if they had lived in Quebec. Then, assuming that absent the program the growth rate of \(y\) would be the same for the treated group in Quebec as it would be for the group that is not treated, then \(\beta _{7}\) identifies the program effect in Eq. 2. Like any DID estimates, the results of this paper assume that, after controlling for observables, the change in outcomes of the comparison groups would be parallel to the counterfactual outcomes for the treated group. Since I am considering one pre-period, I do not control for region specific trends since they would be collinear with the estimate of the program effect. Since the Canadian Human Rights Act was passed in 1977 (Canada 1985) and the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms (Quebec 2008) was passed in 1975, which predates either natural experiment, institutional barriers that may have differentially affected the labor market participation of different demographic groups in Quebec or the Rest of Canada were mitigated.

When considering women beyond childbearing age as a control group, one possible threat to validity is that there may have different labor market and educational environments for women between provinces prior to the 1970s. From 1960 to 1966 Quebec experienced the Quiet Revolution, which was associated with rapid political and ideological changes with the goal of assuring that Quebec “keep up with the rest of modernizing North America” (Pollard and Wu 1998). Because of different exposure to these attitudes and opportunities, this increase in labor force participation may have been in large part due to differences between cohorts. In order to avoid misattributing cohort effects to program effects I implemented two strategies: controlling for cohort by Quebec fixed effects and following a synthetic cohort.

Data

Census Master Files

The empirical analysis used data from the 1986, 1991, and 1996 Canadian Census 20 % Master Files, and analysis was conducted on-site at Statistics Canada in Ottawa. This data set consists of records at the individual level for all individuals in a 20 % sample of households in Canada on Census Day. The age and parity of children in each Census family was reconstructed from individual records. The sample was then restricted to households where the female household head, wife, or female common-law partner was between the age of 25–45 and was a Canadian citizen. Non-citizens were excluded because they were less likely to be eligible for benefits. The lower bound on age was imposed in order to capture women who were likely to have completed their formal education and the upper bound on age was imposed to capture only women who were of childbearing age.

The outcomes that I focused on were births, labor force participation, weekly hours worked, annual earnings, and annual weeks worked. An individual was defined as participating in the labor force if she reported having worked a positive number of weeks in the year preceding the Census year. Earnings refers to employment income in the preceding year and were inflation adjusted to 1986 dollars. Weeks were defined as the self-reported number of weeks worked in prior the calendar year, and, if weeks were not reported because the individual did not work in the previous year, they were recoded as 0. Weekly hours worked corresponds to the number of hours worked in the reference week.

I constructed various control variables. The number of children in the Census family was created by counting the number of individuals under 18 in the Census family. An individual was considered to speak French if she reported “French” or “French and English” in response to a question that asked which official languages she spoke, and similarly, considered to speak English if she reported speaking “English” or “French and English.” An individual was defined as married if she reported being legally married and was considered married or common-law if she was a female wife or common-law partner with a spouse or partner present in the household. Since some women may have been legally married but living separate from their spouses, “married” is not a proper subset of “married or common-law.” Footnote 2 Table 4 presents the means of select variables.

Table 4 is a Table of sample means for women 25–45 who are Canadian citizens. The sample was split by Census as well as by whether an individual resided in Quebec or the rest of Canada. Over the three Censuses, the mean sample ages in both Quebec and the rest of Canada increased. In 1986 the mean age of the sample in Quebec was 34.2, in 1991 the mean age in the sample in Quebec was 34.8, and in 1996 the mean age in the sample in Quebec was 35.6. This corresponds with the aging of the baby boomer population.

As is often discussed, the proportion of women who are married differs dramatically between Quebec and the rest of Canada and changes dramatically over the sample period. Between 1986 and 1996 the proportion of women who were married in Quebec dropped by 26.3 percentage points whereas the drop in the rest of Canada is only 13.5 percentage points. However, the proportion of women who were either in married or common-law partnerships both in Quebec and the rest of Canada was relatively constant across censuses at roughly 70 % of the population. Because of this fact, instead of emphasizing the group of married women I drew particular attention to the combined group of married and common-law women as it was more comparable across provinces.

Labour Force Surveys

The analysis of the effect of maternity benefits on labor supply was performed onsite at Statistics Canada using all of the monthly LFS from January 2000 until December 2008. The LFS is a monthly survey of households that is representative of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population in the 10 provinces; the population in the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut are not sampled. Each month approximately 54,000 households are sampled. The survey design is a rotating panel that follows households for six consecutive months. Following Bertrand et al. (2004) , observations from multiple months were collapsed into pre- and post-periods in order to produce consistent standards errors. For the reasons discussed above, I focused most of my analysis on individuals aged 25–45 inclusive.

In order to identify individuals who were pregnant, births were imputed by finding the month in which the age of the youngest child became zero. For families with older children, this was a change from some nonzero number to zero and for families for which this was a first child it was a change from a valid missing value to zero. Mechanically, this resulted in an undercount of the number of births since births that occurred in the first month an individual was surveyed or births that occurred in families that had another child under the age of one were not counted. Consequently, when considering the fertility effects of the program I focused on whether or not a family had a child under one instead of the constructed birth variable, although both yielded similar results. This construction also undercounted pregnancies in progress. If an individual was pregnant but did not give birth in the six consecutive months she was in the survey, then she would not have been counted as pregnant. Randomization into the sample implies that approximately a third of pregnancies were not counted. This, combined with the age restrictions on the sample mean that I only considered approximately half of the pregnancies that occur in Canada. To account for the mechanical undercount of pregnancies, I produced a bias correction. Footnote 3 Another source of concern with this construction is that it only captured women who were in the last few months of their pregnancies. Perhaps women in their first trimester behaved differently from the pregnant women captured by this construction.

The measures of whether or not an individual participated in the labor force, was employed, and was employed and present at work were taken from self-reported labor force status. Earnings were measured as self-reported weekly earnings in dollars. Hours were measured in two ways: the self reported total number of hours an individual worked in the reference week as well as her self reported usual total hours worked.

Table 5 presents summary statistics for women in Quebec and the rest of Canada before 2006 and in or after 2006. Since the sample was restricted to individuals who are 25–45 inclusive it is not surprising that the mean age of each of the groups the sample was approximately 35.5. High school graduates account for only about 3 % of the populations. However, the group with some post-secondary education includes individuals who self-reported having some post-secondary education who had not received any degree or certificate, who would often be classified as being high school graduates in other studies. Additionally, since the classroom training for apprenticeships may have been obtained during high school but a certificate may not have been attained until after a formal apprenticeship was completed, individuals with trades certification may have been classified as high school graduates under a different system. The group with some post-secondary education includes individuals who self-reported having some post-secondary education and those who had a trades certificate or diploma, community college or CEGEP degree, or a university certificate below a bachelor’s degree.

Something that is very striking from the table of means is that the proportion of individuals who were married in Quebec was much lower than in the rest of Canada. Among women, 40.2 % were married in Quebec prior to 2006 while 62.5 % were married in the rest of Canada at the same time. In or after 2006, these proportions were 33.2 and 59.7 % respectively. The opposite relationship holds for common-law couples. Prior to 2006, 31.0 % of women in Quebec were in common-law relationships compared to 9.6 % in the rest of Canada. In or after 2006, 36.0 % were in common-law relationships in Quebec while only 11.2 % were in common-law relationships in the other provinces. However, the sum of the proportion of individuals who were married and of individuals who were in common-law relationships was remarkably stable and similar across geographic areas: prior to 2006 71.2 % of women in Quebec were in married or common-law relationships compared to 72.1 % in the rest of Canada. In or after 2006 these proportions are 69.2 and 70.9 % respectively. Therefore, the combined group of married and common-law women should be more comparable across provinces than either the married or common-law group.

Theory

In order to fix ideas about the effects of the generosity of cash-transfer fertility incentives on fertility and labor supply, I considered the effects of both types of fertility incentives in the same simple theoretical framework. Suppose that an individual has an additively separable intertemporal utility function in consumption, \(c_{t}\), leisure, \( l_{t}\), and number of children, \(n_{t}\), over a finite number of periods, \(T\). The number of children, \(n_{t}\), is a monotonically increasing, discrete stock of children that can increase by at most one per period. Let the individual’s discount factor be equal \(\beta \le 1\) and assume that \( u\left( \cdot \right) ,\,v\left( \cdot \right) \), and \(z\left( \cdot \right) \) are twice differentiable with positive first derivatives and negative second derivatives.

For a family that does not have any additional children the budget constraint is

where \(w_{t}\) is the period-specific wage and \(p\left( m_{t}\right) \) is the minimum cost of caring for a family of structure \(m_{t}\) so that the cost of children can vary with their ages. While the utility derived from having a given number of children does not change as they age, presumably they eventually grow up and no longer require parental support, so \(p\left( m_{t}\right) \) changes over time even if \(n_{t}\) does not. To simplify things, assume that the path of \(m_{t}\) and hence \(n_{t}\) are predetermined as is the path of wages, \(w_{t}\). This implies that \(\sum _{t=0}^{T}\beta ^{t}z\left( n_{t}\right) \) and \(\sum _{t=0}^{T}\beta ^{t}p\left( m_{t}\right) \) are fixed.

Because of the assumption that the individual’s discount rate is equal to the interest rate, from the first order conditions it is clear that consumption is constant across periods and labor supply is higher in periods where the wage is higher. Since \(c\) and \(l\) are normal goods an increase in nonlabor income net of fixed costs, \(\sum _{t=0}^{T}\beta ^{t}\left[ y_{t}-p\left( m_{t}\right) \right] \), will lead to an increase in consumption and leisure.

First, consider a program that provides cash transfers that are tied to having children, but are not income contingent. For a given path of wages, \(\left\{ w_{t}\right\} _{t=0}^{T},\,c_{t}\) is clearly lower for families with more children since \(p\left( m_{t}\right) \) is at least as high for all \(t\) and higher for some \(t.\) If a program offers transfers that are tied to having children, then the program will have a larger positive impact on the utility of larger families. Comparing utility levels between different fertility paths, \(\left\{ n_{t}\right\} \), demonstrates that the marginal benefit of having an additional child in any period has increased, and the implementation of such a policy should thus also lead to an increase in fertility.

Next, consider a world with parental leave benefits. For a family expecting a birth in period \(1\), let \(b\) be the income replacement rate of maternity benefits. When considering the effects of the generosity of maternity benefits on mothers, one must consider both the case of women who give birth in period \(1\) who would be employed in period \(0\) without the benefit increase and the case of women who give birth in period \(1\) who would not be working in period \(0\) were the old maternity benefit policy in place. For the former, the amount of benefits received under the new program is \(bw_{0}\left( l_{1}-l_{0}\right) \) and, assuming that the interest rate is equal to the discount rate, the woman’s budget constraint is

The assumptions above produce the result that in equilibrium consumption is equal in all periods and, for \(T\ge t\ge 2,\,c^{\prime }\left( l_{t}\right) =w_{t}u^{\prime }\left( c\right) \). Furthermore, \(v^{\prime }\left( l_{0}\right) =\left( w_{0}+\beta bw_{0}\right) u^{\prime }\left( c\right) \) and \(v^{\prime }\left( l_{1}\right) =\left( w_{1}-bw_{0}\right) u^{\prime }\left( c\right) \). Note that this is identical to a situation in which the period \(0\) wage is increased by \(\beta bw_{0}\) and the period one wage decreased by \(bw_{0}.\) Let \(f\) be the inverse function of \(v^{\prime }.\) Then \(f^{\prime }=\frac{1}{v^{\prime \prime }}<0\). Using the equilibrium conditions and substituting them into the budget constraints and differentiating implicitly yields the results that consumption is increasing in the income replacement rate, that is \(\frac{dc}{db}>0\). The effect of the income replacement rate on leisure demand is of ambiguous sign in period \(0\) since the program effectively raises an expectant mother’s wage by \(\beta w_{0}\), which leads to competing income and substitution effects, which are summarized by the following equation

In all periods after period \(0\), demand for leisure is increasing. In period one, the relationship between the income replacement rate is as follows

and for all subsequent periods

so demand for leisure is only affected by the income replacement rate through its effect on consumption.

In the case that an expectant mother would not be employed under the old regime and there are no minimum hours restrictions to the program she similarly maximizes utility in Eq. 3 subject to the budget constraint in Eq. 5. Realistically, most parental leave programs require that a minimum number of hours be worked or that an individual must have minimum earnings to qualify for benefits. Since wages are predetermined, these concepts are equivalent in the model. Let \(\bar{h} =L-\bar{l}\) be the minimum number of hours of work required in period \(0\) in order to qualify for benefits in period \(1\). An individual who would not work under the old policy compares her maximized utility in the scenario in which she does not work in period \(0\) to her maximized utility in the case where she works at least \(\bar{h}\,\ \)hours in period \(0\). If she works at least \(\bar{h}\) in period \(0\), that is, if \(l_{0}\le \bar{l},\) utility is increasing in \(b\) and there is no change in utility if \(l_{0}>\bar{l}\). Therefore, the probability that individuals opt to work at least \(\bar{h}\) hours in period \(0\) increases in \(b\).

Suppose that prior to period \(0\) an individual can decide whether or not to have a child who will be born in period \(1.\) An increase in the income replacement rate, \(b\), has no effect on the individual’s optimization problem conditional on having no additional children. However, for women who would opt to work conditional on having a child in period one under the new policy there is an increase in utility from having a child so more women will choose to have children if benefit levels increase.

Note that the model implies that both cash-transfer fertility incentives and parental leave should increase fertility rates and increase the consumption of individuals who receive benefits. However, cash-transfer fertility incentives unambiguously decrease the labor supply of recipients, while parental leave benefits unambiguously increases the probability that individuals work prior to giving birth and have ambiguous effects on labor supply along the intensive margin.

Results

Because of the parallel structure of the evaluation of each program and the quantity of information presented on each program, the empirical results of the evaluation of cash-transfer fertility incentives are separately.

Cash-Transfer Fertility Incentives

Fertility Effects

Table 6 presents basic DID estimates of the probability of a woman 25–45 of having a child less than one year old. Panel A presents results for all women age 25–45 and Panel B includes controls for demographics. The first column of each panel presents the results for all women and the second through the sixth columns condition the sample on whether a woman had zero, one, two, three, or four or more children, excluding any children less than 1 year old.

Dividing the DID estimate of the program effect for all women of 0.001 from Column 1 of Panel A by the counterfactual probability of a birth in Quebec after 1986 of 0.058 (obtained from evaluating the estimated Eq. 1 with the coefficient on \(Quebec\times Post\) set to zero), shows that the birth rate increased by 1.72 % due to the cash transfer fertility incentives. Moving across Columns 2 through 6 it becomes immediately apparent that the size of the effects differed by the number of children already in a family. Interestingly, most of the additional births due to the cash-transfer program are attributable to first births and births of fifth or higher parity. Given that there was a large increase in benefit levels for having a third or higher parity child, it is surprising that the point estimates of the probability of moving from two to three children are negative and nonsignificant.

Labor Supply of Women of Childbearing Age

Table 7 presents estimates of the impact of cash-transfer fertility incentives on women of childbearing age. Column 1 presents DID estimates for women age 25–45, controlling for cohort fixed effects and demographic characteristics. The 0.9 percentage point increase in labor force participation in Row 1 of Column 1, which suggests an increase in the labor force participation of women age 25–45 due to the program, was not robust to the DIDID strategy with women beyond childbearing age as an additional control group. Footnote 4 Column 2 presents estimates of Eq. 2 with cohort fixed effect for a sample restricted to those born in 1931–1961. The lower bound on birth years was imposed so that women in the control group would not exceed the age of 65 in 1996. This specification yielded an estimated program effect of a 0.8 percentage point decline in labor force participation among women of childbearing age. Column 4 reports results from a similar analysis on a sample restricted to women who were either married or in common-law relationships, and Column 5 reports results from a sample restricted to single women. Interestingly, the decline in labor force participation of all women appears to have been driven by a 1.6 percentage point decline in labor force participation rates of married or common-law women; single women’s labor force participation was not significantly affected by the program. This is unsurprising as married or common-law women were more likely to have children and also likely to have had more financial support outside of their labor earnings. Column 5 presents results for the cohort born between 1956 and 1961 where the cohort born from 1946 to 1941 was used as an additional control group. This specification attributed a 2.3 percentage point decline in labor force participation to the cash-transfer incentives.

Considering the effects of the program on earnings in Row 2 of Columns 2 and 5, it appears that the program reduced earnings of women of childbearing age by approximately C$400 per year. Since earnings among those with positive earnings did not change significantly due to the program in Row 3 of Column 2 and actually increased in Column 5, this reduction in average earnings was likely due to the reduction in labor supply. Similarly, hours in Row 4 declined by 1.5 h per week in Column 2 and 0.7 h in Column 5, yet hours among those who worked in the reference week are unaffected in Column 2 and increased in Column 5. Weeks worked decreased due to the program in Row 6 in the DIDID estimates using older women as controls as well as the DIDID estimates using synthetic cohorts. While it appears that for the cohort born from 1956 to 1961 weeks worked among those who worked at least 1 week during the year did not change in the synthetic cohort DIDID in Column 5, but did decline by 0.6 weeks per year when a cohort fixed effects approach was used.

Once these effects and Quebec-specific trends not attributable to the program are controlled for, it appears that the program led to a decline in labor supply which, except for a small decline in weeks worked among those who worked during the year, are largely attributable to declines in labor force participation.

Effects on the Labor Supply of Women With Children Under Age Six

As is clear from Fig. 2, mothers of children under age six received much larger transfers than women without children under age six. While there may be concerns about selection into the group of mothers with children under age six, using standard instruments for fertility such as Angrist and Evans (1998) use of the sex-composition of the first two births would not have been valid to identify the treatment-on-the-treated effect. The marginal family that decided to have a child because their first two children were of the same sex in Quebec may have differed from the marginal family in the rest of Canada because they faced different costs of an additional child, so the local average treatment effects of the two groups would not be comparable and the instrumented DIDID estimate of the effect of the program would not have identified the true treatment-on-the-treated effects. Similarly, Heckman two-step selection corrections for labor force participation using family composition would have been invalid. Although concerns about selection into motherhood due to the program are warranted, they may not be so severe as the program did not have a sizeable fertility effect, so I proceed without correcting for selection.

Table 8 presents results from DIDID estimates of the effect of the cash-transfer fertility incentives on the labor supply of women age 25–45 who had children under the age of six using all other women age 25–45 as a control group. Column 1 of Table 8 presents program effects where both data from the 1991 and 1996 Censuses were considered to be in one “post” period. Since benefit generosity increased and possible awareness of the programs may also have increased between 1991 and 1996, Columns 3 and 4 present program effects where the 1991 and 1996 Censuses were handled as separate treatment groups. These differences persisted when women were split by marital status.

Column 1 of Row 1 shows that, consistent with the theoretical model, labor force participation among mothers of children under age six declined by 4.1 percentage points due to the program. In 1991 this decline was 2.8 percentage points, and by 1996 this decrease grew to 5.1 percentage points. This decrease in labor force participation contributed to an overall reduction of hours worked of 1.2 h per week in Row 4 and to a reduction in weeks worked of 2.1 weeks per year in Row 6. Also, mothers of young children who worked at least 1 week during the year reduced average weeks worked by 0.9 weeks per year, this could suggest that working women may have been taking more days off due to the program. Interestingly, the average number of hours worked in the reference week for women who reported a positive number of hours worked increased by 0.4 h. Perhaps mothers of young children who participated in the labor force when the programs were in place were more likely to have careers that demand that they work full time.

One of the most striking effects of the program on mothers of young children appears in Row 2. The average decrease in earnings for mothers of young children across both Censuses in Column 1 was C$428, which is significant at the 1 % level. The results in Columns 3 and 4 show that earnings among the average mother of a child age five or under in Quebec declined by C$257 due to the program in 1991 and C$548 due to the program in 1996. To put the magnitude of the effects in perspective, a back-of-the-envelope calculation yields a total provincial loss in earnings among women with children under six in 1986 dollars of C$307.8 million in 1990 and C$649.9 million in 1995, compared to similarly deflated combined costs of the Allowance for Newborn Children and Availability Allowance of C$198.1 million and C$238.9 million respectively (Québec 2005a). The implicit additional cost to the government of Quebec due to the reduction of labor supply, of course, depends on the marginal tax rates on these amounts.

Effects also differed by the age and parity of a woman’s youngest child. To demonstrate this, Table 9 breaks down effects by the age of the youngest child and whether that child was of first, second, and third or higher parities. All of the results are from a single regression that considered the effect of the program on the labor force participation of mothers. The point estimates for the labor supply response along the extensive margin are consistently much larger for women whose youngest child was of parity 3 or higher, which corresponded to much larger incentives. For example, for a woman whose youngest child was 3, for the first parity child the program effect was an nonsignificant decline in labor force participation of 0.2 percentage points, whereas for a woman with a second parity child the effect was a decline of 4.9 percentage points which was significant at the 1 % level, and for a woman with a third or higher parity child, the effect was a decline of 9.6 percentage point which is significant at the 1 % level. Results for other labor market outcomes were similar; patterns analogous to those for labor force participation were found for positive weeks worked.

The Cost of an Additional Child

If labor market effects are not taken into consideration, an estimate of the government cost of an additional birth, \(C_{1}\), to the government is the total cost of the benefits for the average family receiving benefits, \(B\) , divided by the change in the probability of having a birth in a given year, \(\Delta F.\)

An underestimate of \(B\) can be calculated from the total amount paid in Availability Allowance and Allowance for Newborn Children benefits from 1989 to 1996 divided by the total number of women in the population. This is a clear underestimate as it does not take into account the cost of programs such as child tax exemptions. Total transfers paid are obtained from the Régie des Rentes 2004 report, Les Préstations Familiales: Statistiques 2004 (2005a) and the number of women in the population age 25–45 in Quebec is obtained by multiplying the average of the number of women in this group in the 1991 and 1996 Censuses by 5. Taking an average over all 8 years results in an annual program cost per woman of C$174. Dividing by \(\Delta F\), which is taken to be 0.002 from Column 1 of Panel D of Table 6, produces an estimate of a cost per additional birth of C$87,225 in 1986 dollars per child.

Since I demonstrated that the cash-transfer programs led to significant declines in earnings among women of childbearing age and women with young children the loss of tax revenue caused by behavioral responses to the program must also be taken into account. Let this net government cost per additional birth be denoted \(C_{2}\). In the equation below, \(\tau \) is the marginal tax rate, which I take to be 20 %, and \(\Delta y\) is the change in earnings of the average woman due to the program, which, from Row 2 of Column 2 of Table 7, is C$403.

Adding the loss in tax revenue per additional child, \(\frac{\tau \Delta y}{ \Delta F}\), to the cost of the program implies a cost per additional child of C$127,565 in 1986 dollars.

Note that since none of these estimates takes into account the cost of tax exemptions, welfare programs, or public education they are actually underestimates of the fiscal cost of increasing the birth rate. As a point of reference, at a 4 % discount rate Lee and Miller (1997) projected that the fiscal impact of an incremental birth in 1996 to an American high school graduate and all the descendants of the child for the next 300 years would be approximately US$61,000, which is C$61,630 in 1986 Canadian dollars. It should be noted that their calculations sum both state and national fiscal benefits, and that US government policy differs from Canadian government policy, so this estimate is intended to be used only for benchmarking purposes. Since all of the cash-transfer fertility benefits studied in this paper are issued by a provincial government, the government that paid for the fertility incentives does not fully capture the fiscal benefit from the increase in population due to the program.

Parental Leave Benefits

Fertility Effects

Parallel to Table 6, Table 10 presents linear probability models of having a child less than 1 year old. Panel A presents results for all women 25–45 and Panel B adds controls for demographic characteristics. The first column of each panel presents the results for all women in the appropriate subsample and the second through sixth columns are conditional on having zero, one, two, three, or four or more children in the family, excluding children less than 1 year old. Using the DID estimate of the program effect in Column 1 of Panel A and dividing by the counterfactual probability of having a child in Quebec after 2006 of 0.051 shows that the fertility rate increased 23.5 % due to the increase in parental leave benefits. A similar calculation for married or common-law women results in a 26.8 % increase in the birth rate due to the program, and the DID estimate for fertility effect of the program on single women was an increase of births of 0.1 percentage points with a standard error of 0.02 percentage points.

Moving across Columns 2 through 6 of both panels of Table 10, it becomes immediately apparent that the size of the effects differs by the number of children already in a family, with large and strongly significant effects for first and second parity children of parity 1 and 2 as can be seen from Columns 3 and 4. The majority of additional births attributed to the introduction of the QPIP were of first or second parity. Summing the last Rows of Columns 2 and 3 of Panel A of Table 10, 77.3 % of births attributable to the introduction of the program are of first and second parity. Births of second parity represent the largest proportion of the increase, accounting for 45.6 % of additional births.

Because the introduction of QPIP provided a such large increase in benefits there may be have been concerns that the program was temporary. A belief that the program was short lived may have caused families to move up their childbearing in order to take advantage of the program but not actually increase their lifetime number of children. If this were the case, the program would simply affect the tempo of childbearing but not the quantum. Since the program was introduced recently, it is difficult to test whether the fertility effect is merely a tempo effect since women exposed to the program have not completed their childbearing years. Intuitively, if the program was only shifting forward the timing of births then the average age of the women giving birth in Quebec should decrease in the first few years of the program relative to women giving birth in the rest of Canada. Controlling for educational attainment categories and clustering at the individual level, I found that the average age of mothers of infants increased by 0.439 (0.180) years due to the introduction of the program, which is significant at the 5 % level. Footnote 5 This suggests that QPIP is actually increasing total fertility and is not just shifting the timing of births.

Average Labor Supply Effects on Women of Childbearing Age

Since the value of the maternity benefit payments a woman was eligible to receive was increasing in her income in the period before she took leave, there was a clear incentive for women who planned to have children to be employed. Predictions about responses along the intensive margin, however, were less clear as an increase in the replacement rate induces both a income and substitution effect. Knowing the effect of the program on the labor supply of the average woman of childbearing age makes it possible to calculate the cost of the program net of labor supply effects.

Column 1 of Table 11 presents estimates of Eq. 1, the DID estimate of the program effect on various outcome measures among women age 25–45, controlling for age, age squared, and level of education. Rows 1 and 2 make it apparent that women increased their labor supply along the extensive margin in response to the program. Labor force participation increased by 1.5 percentage points and employment increased by 1.7 percentage points. Interestingly, Row 4 shows that the proportion of women who were at work conditional on being employed decreased by 1.7 percentage points. This offsets the increase in participation and employment so, as is evident from Row 3, the proportion of women who were employed and at work did not change significantly. These results suggest that much of the increase in labor force participation and employment may have been due to a change in labeling among women who were employed and not present at work; instead of being out of the labor force they were considered to be on leave. Consequently, when women who were not present at work are included in Row 7, actual total hours worked did not change significantly due to the program. Among those who were employed and present, however, actual hours declined significantly by 0.242 h per week in Row 8, which suggests an increase in the proportion of working women who were working less than full time. Since employment increased, it is unsurprising that self-reported usual total hours worked increased by 0.486 h per week in Row 9 while usual total hours worked among the employed and present did not change significantly in Row 10. The decline in weekly earnings of C$20.98 in Row 5 seems at odds with the increase in labor supply. Although actual hours worked if employed and present declined due to the program, the decline in earnings among those who were employed and present in Row 6 of C$26.65 per week seems large relative to the approximately 15 min per week decline in actual hours worked. This suggests that wages in Quebec did not keep pace with the rest of Canada.

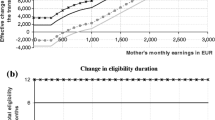

If wages for all workers in Quebec were growing at a slower rate than those in the rest of Canada, then comparison groups are needed that were unaffected by the program. Analogous to methods used in the analysis of cash-transfer programs, I considered men age 25–45, older women, and synthetic cohorts as additional comparison groups, in Columns 2, 3, and 4 respectively. In order verify that these estimate were valid insofar as the DIDID assumption of parallel wage growth paths was met, Fig. 3 presents quarterly graphs of the Quebec/Rest of Canada difference in female-male weekly earnings gaps over time and the female/male difference in Quebec versus rest of Canada weekly earnings, and Fig. 4, presents weekly earnings of the younger cohort increase relative to the earnings of the older cohort in Quebec after the introduction of the program but not in the rest of Canada. Taking the double difference over time, it is clear that prior to 2006 these gaps follow roughly parallel paths, so men and older cohorts are a valid control groups. When men age 25–45 were used as a comparison group in Column 2, earnings of women in Quebec were estimated to have increased by C$17.26 due to the program, and when a synthetic cohort was used as a comparison group in Column 4, weekly earnings among women of childbearing age were estimated to increase C$20.66 per week.

The results presented for all women above suggest that more generous maternity leave benefit replacement rates are associated with higher female employment rates and earnings.

Effect of QPIP on the Labor Supply of Women Eligible for Transfers or Eligible to Qualify for Transfers

Beyond the effect of the program on the average woman it is of obvious importance to quantify the extent to which women were directly affected by the program. In the theoretical framework women who are pregnant in period 0 can adjust their labor supply in order to qualify for benefits in period 1, and women who have an infant in period 1 qualify for benefits that effectively decrease their wage if they worked. The first column of Table 12 presents the estimated DIDID program effects for women who were imputed to be pregnant and the second column presents the program effect for women who had babies less than 1 year old, controlling for individual characteristics. Because the presence of children other than infants may also have strong effects on the labor supply of women, I controlled for the age composition of a woman’s children using the number of children in particular age categories. I adjust for the bias as follows: For each geographic region by period group I calculate the pregnancy rate in the population, \(\pi \), by taking \(\frac{9}{12}\) of the birth rate, and recover group specific \(E\left[ \bar{y}_{p}-\bar{y}_{n}\right] \) and \(E\left[ \bar{y}_{b}-\bar{y}_{p}\right] \) from regression results. Note that if the undercount of pregnancies was the only source of bias, then \(\mu _{baby}-\mu _{pregnant}=\bar{y}_{baby}-\bar{y}_{pregnant}.\) Comparing the last two columns to the first two in Table 12 it appears that the bias is negligible.

Concentrating first on the effects on pregnant women in Column 1, the effects of the program on labor market status in the first four rows are nonsignificant but suggest that, consistent with the model, women may have started employment in order to receive benefits and may have begun taking them up late in their pregnancies. Row 9 shows that there was an average increase of 3.32 usual hours worked per week among all women who were pregnant and an average increase of 2.85 usual hours worked per week among women who were pregnant and employed and present at work, which is significant at the 1 % level. As I mentioned earlier, usual hours worked are a measure of general labor force attachment so this may indicate that women with stronger labor force attachment were becoming pregnant. Among pregnant women who were present at work, there was a significant C$105.58 increase in weekly earnings in Row 6 and an increase of 2.15 h actual hours worked in the reference week in Row 8. These results suggest that women may have been increasing their labor supply along the intensive margin while pregnant in order to increase their benefit payments.

Focusing on the effects of the program of the program on women who had an baby under a year old, it appears that the results were driven primarily by leave-taking. Among these mothers, there does not appear to have been a discernible change in labor force participation in Row 1 of Table 12 or employment rates in Row 2. However, consistent with the theoretical model, the proportion who were employed and at work declined substantially by 5.2 percentage points in Row 3. Among mothers of infants who were employed, the proportion who were present at work declined by 5.3 percentage points in Row 4. Among those who worked, earnings increased insignificantly by C$52.97 in Row 6. This may have be due to differences in who selected into being present at work due to the program. For example, those whose salaries exceed the C$60,500 insurable earnings cap may have received a bigger increase in benefits from the introduction of QPIP, but the opportunity cost of taking maternity leave was still quite high. Considering the results of Row 7 and 8 it appears that the decline in hours is driven for the most part by a decrease in mothers being present at work; actual hours worked for this group declined by a statistically significant 1.31 h per week due to the program while actual hours conditional on being present at work increased by a statistically nonsignificant 1.99 h per week. Mothers of infants were not changing their labor force attachment in response to the program; estimates in Rows 9 and 10 show that usual hours worked did not change significantly. I found similar results when I restricted the sample to married and common-law women.

Cost Per Additional Child

In order to calculate the cost of an additional child given the program I calculated the cost per woman of the program and divide through by the change in fertility due to the program. The weekly cost of the program per woman, \(C\), is calculated as follows,

where \(\rho \) is the probability of having a child under 1, \(\nu \) is the probability of takeup, \(B\) is the average payment to mothers conditional on having a child and taking up, \(\tau \) is the marginal tax rate, and \(y\) is unconditional earnings.

Let \(B^{0}\) denote a woman’s benefit level under the old program and let \(B^{1}\) denote her benefit level under the new program. Since the maximum replacement rate under the federal program was 55 % and the maximum insurable earnings were C$39,000 while the maximum replacement rate under the regular QPIP program was 70 % and the maximum insurable earnings were C$60,500 the following relation must hold

which implies

where upper bars denote means. In 2006, \(\bar{B}^{1}\), the average weekly benefit transferred to mothers was C$408 (Québec 2007), and we can use this result to get an upper bound on \(\Delta \bar{B}\) of C$201.35. The takeup rate, \(\nu \), was calculated as the product of the proportion of women who had infants in Quebec who were employed with the proportion of women who had infants and who were employed but were not present at work. In this sample the proportion is 0.56.

In 2006 and 2007 the provincial tax rate on the first C$29,289 of taxable income was 16 %, the tax rate on income from C$29,290 to C$58,594 was 20 %, and the tax rate on income above C$58,595 was 24 %. In 2008 the threshold were revised to C$37,500 and C$75,000 respectively (Revenu Québec 2008). For the sake of simplicity, I assumed that \(\tau =0.2\). I took \(\Delta y\) to be C$17.26, the value from using men as a comparison group in Row 5 of Column 3 in Table 11. I found that \(\rho \nu \Delta B\), the additional cost of benefits per woman, was C$7.10 and the additional tax revenue per woman, \(\tau \Delta y\), was C$3.45, for a net weekly cost per woman of C$3.65.

Taking the additional weekly cost benefits per woman, multiplying by 52 weeks of possibly having a child under 1, and dividing through by the 1.2 percentage point increase in fertility yields an average cost per additional birth in increased benefits of C$30,782. However, this cost was offset by C$14,954 in additional tax revenue due to the increase in labor supply due to the program, resulting in a net government cost per additional birth of C$15,828. As a basis of comparison, the Lee and Miller (1997) projection that the fiscal impact of an incremental birth in the United States is C$102,161 in 2008 Canadian dollars. Therefore the increase in benefit generosity due to QPIP may have resulted in a large fiscal benefit in the long run.

QPIP was financed by a payroll tax imposed on all employers, employees, and the self-employed. In 2006 the program-specific tax rate was 0.416 % levied on employees 0.583 % levied on employers, which offset a reduction in federal payroll Employment Insurance taxes of 0.340 %. Using revenues from the payroll tax and tax rates for those who were not self-employed reported by the Conseil de Gestion de l’Assurance Parentale Québec (2007, 2008, 2009), this payroll tax resulted in an additional C$1.9 billion dollars in revenue from 2006 through 2008 relative to the case where tax rates were kept at the federal level. The revenue raised per additional child born to women age 25–45 can be estimated multiplying the C$1.9 billion in increased revenue by the proportion of births that occurred to women 25–45, which I assumed to be 80 %, dividing through by number of life-years lived by women age 25–45 in 2006 through 2008 (Statistics Canada 2009), and dividing through by the 1.2 percentage point increase in the birth rate shows that an additional C$47,856 was raised per child born. Given that this more than offset the net government cost per child of C$15,828, the payroll tax levied to support the program may have been too high.

Conclusion

This paper has added to the evidence that pronatalist policies have distortionary effects on labor markets, and it is therefore fiscally prudent to take labor supply effects into account when designing fertility incentives by evaluating the cash-transfer fertility incentives that were introduced in Quebec in the late 1980s and 1990s and the QPIP that was introduced in 2006. I demonstrated that cash-transfer fertility incentives have minor impacts on fertility but, consistent with theory, reduce the labor supply of mothers of young children. In contrast, increasing the generosity of parental leave benefits increases the birth rate substantially and also induces increases in the labor supply of women of childbearing age. This article provided a cost-benefit analysis that makes it possible to directly compare the cost and benefits of cash-transfer versus parental leave policy, which has not previously been done in the literature. These very different responses result in a large difference in the estimated cost per additional birth due to the program: the estimate net government cost of an additional birth due to an increase in parental leave benefits is C$15,828 in 2008 Canadian dollars, whereas the cost of an additional birth due to cash-transfer fertility incentives is C$223,628 in 2008 Canadian dollars (C$127,565 in 1986 Canadian dollars).

The effects of both sets of programs are heterogeneous by the parity of the child: the increase in births due to cash transfers was driven primarily by first births whereas 68 % of the increase in births attributable to QPIP were of second or higher parity. When designing fertility incentives, policymakers should take into account how they may affect the quantum of fertility. For example, if they believe that larger families are more desirable due to returns to scale within families, then they should favor parental leave benefits.

The magnitude of the estimates of the program effects is attributable in part to the Canadian context. Unlike the United States, the price of health care does not vary discontinuously with hours worked. This may give Canadian workers more flexibility in choosing their hours along the intensive margin, since there is not a similar kink in total compensation at 30 hours worked per week as in the United States. Nevertheless, the effects of implementing similar policies in other political systems should be qualitatively similar.

Since the intent of many fertility programs is to increase the future tax base by increasing the next generation’s workforce, it will be interesting to see how these programs affect the outcomes, particularly with respect to labor supply and education, of the cohorts who were born when the programs were in place. This could operate through multiple mechanisms. For example, since mothers are about five percentage points more likely to stay at home with their infants, does this have any effect on the wellbeing of the average child? If the effects are in line with Baker and Milligan (2008), who found that extended leave taking due to the extension of the duration of maternity leave benefits led to increased duration of breastfeeding and favorable infant outcomes, beyond achieving a larger future workforce a second order effect might be a healthier workforce. While this is outside of the scope of this paper, it is also feasible that in the long run educational investments may increase among women who anticipate being better able to balance family and career.