Abstract

We examined the construct of financial wellness and its relationship to personal wellbeing, with a focus on the role of financial literacy. Gender comparisons are made using a structural equation modeling analysis including personal wellbeing, financial satisfaction, financial status, financial behavior, financial attitude, and financial knowledge. Males ranked higher in financial satisfaction and financial knowledge whereas females ranked higher in personal wellbeing. Joo’s (2008) concept of financial wellness as multidimensional is supported though the result is improved when a causal model of sub-components is estimated. The relationship of all variables to personal wellbeing is mediated by financial satisfaction, with gender differences: In females the main source of financial satisfaction is financial status whereas in males it is financial knowledge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A concerted effort has been made over the past decade by both governments and private organizations to assist and educate individuals in areas of financial management, though it has a much longer history.Footnote 1 Definitions and objectives vary, as does the effectiveness of these initiatives (see Willis 2008). In Australia, the Financial Literacy Foundation, established by the federal government, articulates the following definition and objectives:

Financial literacy is about understanding money and finances and being able to confidently apply that knowledge to make effective financial decisions. Knowing how to make sound money decisions is a core skill in today’s world, regardless of age. It affects quality of life [emphasis added], opportunities we can pursue, our sense of security and the overall economic health of our society (Australian Securities and Investments Commission 2011, p. 4).

This paper examines the quality of life dimension that may be impacted by financial literacy, and investigates more broadly the concepts of financial wellness, financial satisfaction, and overall personal wellbeing; as well as the role of financial literacy.

Personal financial wellness is defined as an active and desirable status of financial health, and “a comprehensive, multidimensional concept incorporating financial satisfaction, objective status of financial situation, financial attitudes, and behavior that cannot be assessed through one measure” (Joo 2008, p. 23). Joo also proposed a model where personal financial wellness is differentiated from other related (but more restricted) terms such as economic, financial or material wellbeing.

In this paper we use the term financial wellness as defined by Joo (2008) instead of the term financial wellbeing because financial wellbeing has been variously defined with a wide variation in scope. For example, Greninger et al. (1996) used a Delphi study of financial planners and educators to produce a profile of financial wellbeing for a typical household, focusing on a range of financial ratios including liquidity, savings and household expenses derived from objective financial measures. In addition to objective measures, subjective judgments were also used to provide an insight into individual perception and affect. Kim and Garman (2003), for example, included the individual’s perception of his or her ability to meet expenses and a tendency to worry about debt, among other factors.

Prawitz et al. (2006) highlighted the range of labels that have been used in the literature to measure the construct. Positive labels include perceived economic wellbeing, financial satisfaction, and financial wellness; while negative labels include financial stress and financial strain. These authors proposed a perceived financial distress/financial wellbeing measure to represent the “continuum extending from negative to positive feelings about, and reactions to the financial condition” (p. 36). Following a Delphi study of education experts in the field, Prawitz et al. settled on eight subjective items to form their measure.Footnote 2

In this article we follow Joo’s (2008) proposed model and view personal financial wellness as an overarching concept that includes financial satisfaction, among other factors. It therefore follows that we consider financial satisfaction to be a dimension of financial wellness. In order to measure financial satisfaction we used a reduced version of Prawitz et al.’s (2006) measure of financial distress/financial wellbeing. In the remainder of the paper we refer to this measure as “financial satisfaction” and view it as a component of financial wellness. Joo indicated that the concept of personal financial wellness was highly popular but poorly understood, with no measures of financial wellness having been developed. She described personal financial wellness as a comprehensive, multidimensional concept and proposed four criteria to identify persons with high financial wellness: satisfaction with own financial situation; desirable objective status; positive financial attitudes; and healthy financial behavior.

To differentiate between similarly labeled concepts, Table 1 provides a theoretical description of the main concepts covered in this paper and how they have been operationalized.

Figure 1 depicts Joo’s (2008) conceptual framework of personal financial wellness. Personal financial wellness is composed of four sub-components: objective status; financial satisfaction; financial behavior; and subjective perception. Joo further proposed this framework as the first step towards a better understanding of the concept of financial wellness. This claim is used as the basis of our mathematical formalization of Joo’s framework.

Model of financial wellness—Joo (2008)

In addition to developing a formal model of financial wellness, we examined the relationship between personal financial wellness and personal wellbeing. Personal wellbeing has been measured in a number of ways: subjective wellbeing, happiness, life satisfaction, and general wellbeing. These concepts overlap to a large extent, but as is common in psychology, a different mode of measuring a construct goes hand-in-hand with a different conceptualization. Nonetheless, the psychological literature on wellbeing is consistent in concluding that there are a large number of different factors which contribute to personal wellbeing. For example, being employed, living with a partner, being healthy, and having social contact, have all been shown to influence greater personal wellbeing (Dolan et al. 2008). Income also has a positive influence on personal wellbeing, however its effects diminish as income increases (Dolan et al. 2008). Standard of living is therefore a better predictor of personal wellbeing (Dolan et al. 2008).

Kahneman et al. (1999) asserted that there were multiple levels at which quality of life may be studied, of which subjective wellbeing is one such level. Van Praag et al. (2000) produced a structural model of general satisfaction/wellbeing comprising six distinct “domain satisfactions” viz., job, financial, house, health, leisure, and environment; in addition to a vector of individual characteristics including age, income, and gender—all predictors of each of the domain satisfactions.

Cummins (1995, 2000, 2010) developed the homeostatic theory of subjective well-being, which proposed that subjective wellbeing is held under homeostatic control. This is achieved through an integrated system that encompasses the first order personality subsystem and the second order internal buffer subsystem. The primary subsystem is characterized by extroverted and neurotic personality factors that provide a genetically determined range for subjective wellbeing, while the secondary subsystem comprises a set of beliefs about perceived control, self-esteem, and optimism. The latter is less rigid and helps to maintain the range of subjective wellbeing factors when negative life events occur. This study uses the measure of personal wellbeing developed by Cummins (1995, 2000, 2010) and the International Wellbeing Group (2006), the personal wellbeing index-adult (PWI-A).

Joo’s (2008) model included the term “financial knowledge,” which resembles the more popular term “financial literacy.” Research into financial literacy has shown that it is strongly related to consumer behavior. Hilgert et al. (2003) showed a strong correlation between financial literacy and everyday financial management. Studies have found that individuals with greater financial literacy tend to participate more in financial markets (e.g., Christelis et al. 2010; Van Rooij et al. 2011a). Van Rooij et al. (2011b) also showed that numeracy is related to successful retirement planning. In this paper we use Joo’s definition of financial knowledge and several measures thereof: knowledge of retirement savings,Footnote 3 knowledge of financial products, financial general knowledge, mathematical knowledge, and a subjective assessment of participants’ financial knowledge.

Overview of the Study

Joo’s (2008) model assumes that financial wellness is a component of personal wellbeing, comprising financial satisfaction, financial status, financial behavior, financial attitudes, and financial knowledge. Figure 2 shows our implementation of Joo’s model as a structural equation model. Financial wellness is a latent variable that in turn, comprises five latent variables: financial satisfaction, financial status, financial behavior, financial attitudes, and financial knowledge, as indicator variables. In other words, these five latent variables are dimensions of financial wellness with a number of measured indicator variables, as described in Joo’s model. A full explanation of the numbers in Figs. 2, 3 and 4 is presented in the “Results” section.

Estimates of Joo’s (2008) model of financial wellness

Although Joo’s (2008) model viewed financial wellness as a component of personal wellbeing, there is a causal link between financial wellness and personal wellbeing in our SEM implementation of her model. The reason for this is that we turned Joo’s assumption into a testable hypothesis: If financial wellness is a component of personal wellbeing, then an increase in financial wellness can be associated with an increase in personal wellbeing. Two further models were used: the unstructured model (Fig. 3) and the sequential model (Fig. 4). The unstructured model assumed that financial wellness is a composite measure of all the indicator variables used in Joo’s (2008) model, but eliminated all the subcomponents. As with Joo’s model, we turned the assumption that financial wellness is a component of personal wellbeing, into a testable hypothesis.

The sequential model also allowed us to test financial wellness as a component of personal wellbeing. This differs from both Joo’s (2008) model and the unstructured model, in that financial wellness was not considered a composite measure of all the subcomponents. Instead, it theorized that the subcomponents interact with each other and have different degrees of relationships with personal wellbeing. The SEM analysis of the sequential model aimed to determine the actual relationships between the components of financial wellness, and the relationship between those components and personal wellbeing. In this model, financial wellness was not a latent variable as in the previous models, but was implied by the five latent variables (as proposed by Joo’s model), rather than being another latent variable.

Note that there is a minor difference in our implementation of Joo’s (2008) framework in that financial attitudes and financial knowledge are sub-constructs of subjective perception in the original model. However, in psychological literature, attitudes and knowledge are regarded very differently and are examined in different sub-disciplines: Attitudes are studied in social psychology and personality, whereas knowledge is a component of cognitive psychology. For this reason, attitudes and knowledge are separated. Furthermore, this study uses the more technical term “personal wellbeing” instead of “overall wellbeing” as used by Joo, in order to respect the origins of the scale used for measuring the construct in this research (see International Wellbeing Group 2006).

In order to compare the three models, we developed a survey with an inventory of personal wellbeing and financial satisfaction combined with various measures of financial behavior, financial attitudes and financial knowledge, and surveyed a sample of 505 participants. We then used structural equation modeling to test the degree of the relationship between the variables in this framework, as well as the overall fit of the models.

Method

Survey Design

The survey included inventories that measured personal wellbeing and financial satisfaction; and various measures of financial status, financial behavior, financial attitudes, and financial knowledge. Each of these variables is explained below. A full listing of questions is contained in the “Appendix”.

Personal Wellbeing

Wellbeing was measured using the PWI-A (International Wellbeing Group 2006), which contained 8 items and an overall wellbeing question that was used by the International Wellbeing Group to validate the index. Participants indicated their degree of satisfaction in different areas of life: life as a whole, standard of living, health, achievements in life, personal relationships, present safety, feeling part of a community, future security, and spirituality or religion. For each item, participants were asked to indicate a value from 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied), with 5 being neutral. A personal wellbeing score was arrived at for each participant, by obtaining the average value of these nine items and multiplying them by 10.

Financial Satisfaction

The inventory included six of the items in Prawitz et al.’s (2006) measure of financial distress/financial wellbeing. Participants were asked to indicate their degree of financial stress on a scale from 1 to 10. For example, “on a scale of 1–10 where one is “overwhelmingly stressed” and ten is “no stress at all,” what do you feel is the level of your financial stress today?”

Financial Status

The three variables used to measure financial status were household income, household assets, and household debt. Participants were asked to classify their household according to a category of income, a category of assets, and a category of debt.

Financial Behavior

Several measures of financial behavior were used. In this analysis we only used measures that were good predictors of financial behavior. The three relevant predictors were: identifying a figure for retirement (figure), consulting an accountant (acc), and consulting a financial planner (fplan) (see “Appendix” section). All these were dichotomous variables.

Financial Attitudes

We obtained several measures of financial attitudes and again, only used two that were good predictors of financial attitudes: the importance of keeping up to date with finance (uptodate); and the importance of superannuation (superimportance).

Financial Knowledge

Five measures of financial knowledge were obtained from a number of questions: financial general knowledge (five questions) (fgk); knowledge of financial products (six questions) (kfp); superannuation general knowledge (five questions) (sgk); mathematical knowledge (five questions) (math); and subjective financial knowledge (one question) (sfk). A value was determined for each of these predictors by calculating the average number of correct responses, except for sfk, where the value indicated in the one relevant question was used.

Sample

A commercial survey company was engaged to administer the survey by telephone to a random sample of individuals in the state of Western Australia. The random sample identified 1,668 potential participants, from which contact was made with 643 eligible participants. Completed surveys were obtained by telephone from 505 participants. Table 2 provides a comparison of the sample characteristics with the broader population. The sample was evenly split by gender (50.1 % female), and included a broad range of age groups. Relative to the broader population the sample was older, with a median age group of 50–59 years, as compared with a median age group of 40–49 years for the broader population. In terms of employment and retirement status, comparable statistics for the broader population (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009) are available for those aged 45 years and older, and reveal a similar breakdown. In the sample (population), 46 % (50 %) were employed and 31 % (41 %) retired. The highest level of education of those included in the sample was also comparable with the broader population,Footnote 4 although 34 % of the sample had a university qualification, as compared with 24 % in the broader population. Partnered respondents comprised 66 % of the sample which was higher than that for the broader population (59 %) (Commonwealth of Australia 2008). Finally, the distribution of household income in the sample was comparable with the broader population, with a marginally smaller (larger) proportion of households in the highest (lowest) income group.

Structural equation modeling allowed us to take only gender into account in the analysis. Although this may be considered a weakness of the study, previous research has shown that other demographic variables like age, ethnicity, marital status, education, and the number of financial dependents are only indirectly related to financial satisfaction (Joo and Grable 2004). In addition, an analysis of the distribution of each demographic by gender in the current sample suggests that the only significant difference is household structure, with 74.8 % of males in a partnered relationship as compared with 56.4 % of females. However, an examination of financial wellbeing among women (Malone et al. 2010) found that marriage was not associated with greater financial well-being.

With the exception of financial status variables (i.e., household income: 10.5 % missing values; household assets: 14.3 % missing values; household debts: 12.3 % missing values) which were retained because of their importance, all other variables with more than 10 % of missing values were analyzed. Imputation, as described in SPSS Inc. (2009), was utilized for retained variables with missing values.

Procedure

Structural equation modeling requires the construction of measurement models and structural models. Measurement models contain both latent variables (not measured) and indicator variables (measured). The latent variables were chosen based on theory. In the three structural models developed (see below in this section), we used the latent variables proposed by Joo’s (2008) model of financial wellness. Figures 2, 3 and 4 show the latent variables of the three models in the oval shape, with each of the headings previously discussed in the “Survey Design” section (above) corresponding to a latent variable. Each latent variable has its own indicator variables, chosen on the basis of how much variance was accounted for by the latent variables in the measured variables. The indicator variables are also described in the “Survey Design” section below, and the questions that were used to measure them are shown in the “Appendix”. Indicator variables that correlated poorly with the latent variables (i.e., they had low factor loadings) were excluded, and are not reported here.

Structural models depict latent variables and the connections between them. To test Joo’s (2008) proposal that financial wellness contains sub-components, we developed a structural model with sub-components (Joo’s model) and compared its goodness of fit with that of a structural model without sub-components (unstructured model). Additionally, we investigated whether there is a causal relationship among the sub-components of financial wellness. Since Joo’s model does not implement any relationship among the sub-components, we developed a third structural model (sequential model) which contains causal relationships among the sub-components of financial wellness. Therefore we investigate: support for Joo’s proposal; an alternative to Joo’s model in the unstructured model; and a sequential model which if supported would be evidence that Joo’s model has some value (i.e., the proposal of sub-components is adequate), but that it is incomplete, and that a causal relationship between sub-components should be added to the model. This analysis was also conducted separately by gender, thereby producing six structural models.

In both Joo’s (2008) model and the sequential model, we generated a measurement model for the latent variables of personal wellbeing, financial status, financial behavior, financial attitudes, and financial knowledge. In Joo’s model, financial wellness used the other latent variables as indicators, therefore requiring no measurement model. Financial satisfaction did not require a measurement model because it contained only one indicator variable. In the unstructured model we used the same predictor variables of financial wellness as in Joo’s model. In the sequential model, financial satisfaction did not require a measurement model because it contained only one predictor variable, and as explained earlier, financial wellness was not a latent variable but was implied by the combinations of the other latent variables.

Our implementation of Joo’s (2008) structural model included seven latent variables: personal wellbeing; financial wellness; financial status; financial satisfaction; financial behavior; financial attitudes; and financial knowledge. This model encompassed three layers: the first layer examined the personal wellbeing variable; the second layer examined the financial wellness variable; and the third layer examined the subcomponents of financial wellness viz., financial status, financial satisfaction, financial behavior, financial attitudes, and financial knowledge. Based on Joo’s assertion that financial wellness is an overarching concept and cannot be assessed by only one measure, it is represented in our model by a latent variable that does not have direct indicator variables. Instead, its indicators are the other latent variables.

In the unstructured model we eliminated the third layer of Joo’s model so that it contained financial wellness without subcomponents, but included a latent variable with 14 indicator variables. Unlike the other two models, the sequential model hypothesized that the subcomponents of financial wellness are related to each other. In the construction of the sequential model we examined goodness of fit of different links between the six latent variables, as well as the links between personal wellbeing and these six latent variables. In each estimation, the following restriction was applied: Financial knowledge was placed at the beginning of the sequence (motivated by the financial literacy literature which indicates that financial knowledge is responsible for positive consumer behavior), and personal wellbeing was placed at the end of the sequence (following Joo’s model) with the other five variables in between these two. After this examination, we retained the weightings that best fitted the male and the female data. Thus the reported variable weightings presented in Fig. 4 indicated the best fit of all the possible sequential models (given the restrictions explained above) for males and females. The measurement and structural models were generated using AMOS 19.

Analysis

As previously described, the measurement models were constructed using the variables with higher factor loadings. Once the structural models were created, the overall fit (χ2) of each model was estimated and is reported together with its associated significance. However, given the large sample size this is more for illustrative purposes as we expected significant χ2 values. A model was considered to have a good overall fit if the Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI) was higher than 0.90, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was lower than 0.05 and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was smaller than that of the saturated model.Footnote 5 The critical ratio (CR) was used as a measure of significance of the estimates with CRs higher than 1.96 or lower than −1.96 considered significant. The difference between models was compared using BIC. As Raferty (1995) proposed, a difference of 10 in BIC is a very strong evidence in favor of one of the models, the lower BIC being the best model.

One model was fitted to the data for males and another to the data for females. The difference between males and females was compared, using the variation of χ2 between an unrestricted model that allows all the parameters to differ between males and females, and one that kept the structural and measurement parameters equal in males and females.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Gender Comparison

Table 3 describes the statistics of the variables used in the structural equation modeling analysis. It shows the mean and standard deviations in each variable for females, males and for the whole sample. It also shows a t test comparison between means, and the statistical significance levels for this test.

A significant gender difference in financial satisfaction between females (M = 6.88, SD = 2.16) and males (M = 7.29, SD = 1.99) is evident. The average personal wellbeing index (M = 73.6, SD = 14.3) is within the normative ranges of Western countries (70–80) and Australia (73.4–76.4) (International Wellbeing Group 2006), with females having a higher score (M = 74.6, SD = 15.4) than males (M = 72.7, SD = 13.1). However, this difference is not statistically significant. The scores are within the normative ranges for Australia (females = 74–77.3; males = 72.5–75.9); (International Wellbeing Group 2006), and are also consistent with Louis and Zhao (2002) who did not find gender differences in wellbeing.

The “overall life satisfaction” score presents slightly different results. The mean (M = 78.0, SD = 18.2) is higher than that of the personal wellbeing index, and females (M = 79.7, SD = 19.1) score significantly higher than men (M = 76.3, SD = 17.1). Alesina et al. (2004) also found gender differences in “happiness.” Mixed evidence about gender differences in “subjective wellbeing” led Dolan et al. (2008) to suggest that gender effects on wellbeing are mediated by other variables. “Financial status” is a key variable expected to mediate “life satisfaction” and “overall personal wellbeing.” Males reported higher income and assets groups than females (male income group: M = 4.17, SD = 1.98; male assets group: M = 6.96, SD = 2.08; female income group: M = 3.7, SD = 1.89; female assets group: M = 6.02, SD = 2.32). The difference between males (M = 2.99, SD = 2.38) and females (M = 2.64, SD = 2.02) in household debt is not significant. The structural equation analysis below, further investigates the variables that mediate the gender effect on wellbeing.

In terms of reported financial behavior, 52 % of respondents had consulted an accountant in the last 5 years, 41 % had identified a figure for retirement, and 38 % had consulted a financial planner in the last 5 years. There were significant gender differences in the proportion of participants consulting an accountant (males: M = 0.58, SD = 0.49; females: M = 0.47, SD = 0.50), and the proportion of participants who had identified a figure for retirement (males: M = 0.50, SD = 0.48; females: M = 0.32, SD = 0.45). This was not the case for the proportion of people consulting a financial planner. In “financial attitudes” there were no gender differences in the importance of keeping up to date with finance (males: M = 3.32, SD = 0.80; females: M = 3.23, SD = 0.74) or in the perceived importance of superannuation/retirement savings (males: M = 4.47, SD = 0.95; females: M = 4.49, SD = 0.83).

Finally, significant gender differences were evident in general financial knowledge (males: M = 6.17, SD = 1.47; females: M = 5.69, SD = 1.72), knowledge of financial products (males: M = 3.93, SD = 1.19; females: M = 3.35, SD = 1.24), mathematical knowledge (males: M = 4.21, SD = 0.86; females: M = 3.79, SD = 1.29), and subjective knowledge of finance (males: M = 3.30, SD = 0.99; females: M = 2.92, SD = 1.03); but not in superannuation general knowledge (males: M = 3.90, SD = 0.91; females: M = 3.75, SD = 1.06). In short, males performed better than females in the range of knowledge questions and assessed themselves as having a higher level of knowledge.

Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

Our implementation of Joo’s (2008) framework of financial wellness (Fig. 2) presented a poor fit for males and females (males: χ2 [100] = 296.7, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.871, RMSEA = 0.089, BIC = 495.8 [saturated model BIC = 752], number of free parameters = 36; females: χ2 [100] = 274.1, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.881, RMSEA = 0.083, BIC = 473.3 [saturated model BIC = 752.5], number of free parameters = 36). However, all the parameters relating to the subcomponents of financial wellness and the overarching variable financial wellness were significant for males, and all but one (financial wellness/financial attitude) were significant for females. See Fig. 2 for the standardized regression weights and critical ratios. The variance of personal wellbeing in this model accounted for 8.4 % of males and 16.4 % of females, which provides only weak support for Joo’s (2008) concept of financial wellness as containing subcomponents.

In Fig. 2 financial wellness was implemented as a latent variable with five latent variables as predictors (financial satisfaction, financial status, financial behavior, financial knowledge, and financial attitude). The figures in bold correspond to males and those in square brackets correspond to females. The values above “personal wellbeing” indicate the variance of personal wellbeing accounted for by the model. The first value above the arrows indicates the standardized estimate, and the second bracketed value is the critical ratio where 1.96 is the minimum required for significance. Financial status does not have a critical ratio because its variance was fixed.

In order to investigate the validity of grouping variables in subcomponents of financial wellness, we applied a model that included all the measured variables in the previous model as indicator variables of financial wellness i.e., the unstructured model (Fig. 3). The goodness of fit of the unstructured model was not nearly as good as Joo’s (2008) model for both males and females (males: χ2 [104] = 326.5.7, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.856, RMSEA = 0.092, BIC = 503.4 [saturated model BIC = 752], number of free parameters = 32; females: χ2 [104] = 363.1, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.842, RMSEA = 0.099, BIC = 540.2 [saturated model BIC = 752.5], number of free parameters = 32). All the parameters were significant and the variance of personal wellbeing accounted for 4 % of males and 9 % of females.

In Fig. 3 financial wellness is implemented as a latent variable with a number of predictors. The figures in bold correspond to males and those in square brackets correspond to females. The values above “personal wellbeing” indicate the variance of personal wellbeing accounted for by the model. The first value above the arrows indicates the standardized estimates, and the second bracketed value is the critical ratio where 1.96 is the minimum required for significance.

As mentioned, the previous results provide weak support to Joo’s (2008) model of financial wellness. Although Joo’s model did not fit well, it was nevertheless better than a model without any components of financial wellness. This may suggest that the relationship between the components are different to that in Joo’s model, which does not propose any causal relationship between components. Prompted by the financial literacy literature, different combinations of subcomponents, in which financial knowledge was at the beginning of the sequence and personal wellbeing at the end, were explored. This examination was carried out separately for males and females.

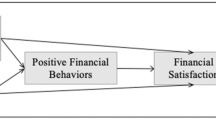

Figure 4 shows that there was a difference between the male and female models. In the female model, the parameter that links financial status to financial satisfaction was estimated, and the parameter that links financial knowledge to financial satisfaction was set at zero. The opposite was true for the male model. The results suggest that males’ financial satisfaction relies on their financial knowledge, whereas females’ financial satisfaction is more strongly linked to their financial status. The fit of these models is far better than that of the others (males: χ2 [101] = 225.3, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.901, RMSEA = 0.07, BIC = 418.8 [saturated model BIC = 752], number of free parameters = 35; females: χ2 [101] = 189.7, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.911, RMSEA = 0.059, BIC = 383.4 [saturated model BIC = 752.5], number of free parameters = 35). The variance in personal wellbeing in this model accounted for 26 % of males and 33 % of females.

The sequential model also allowed us to measure the variance explained in other subcomponents of financial wellness. The variance in financial behavior accounted for was 55 % in males and 44 % in females; the variance in financial status accounted for was 69 % in males and 64 % in females; and the variance in financial satisfaction accounted for was 11 % in males and 16 % in females.

In Fig. 4, unlike the other models, financial wellness was not implemented as a latent variable, but as the whole set of connections among the components of financial wellness (i.e., financial knowledge, financial attitude, financial behavior, financial status, and financial satisfaction). The figures in bold correspond to males and those in square brackets correspond to females. The values above the latent variables indicate their variance accounted for by the model. The first value above the arrows indicates the standardized estimates, and the second bracketed value is the critical ratio where 1.96 is the minimum required for significance. The zero values in arrows connecting variables means that there was no link between those variables in the corresponding model.

Table 4 presents a summary of the models. The sequential model is superior to both Joo’s (2008) model and the unstructured model for both males and females. It has a lower BIC and RMSEA than the others and better explains a greater proportion of the variance in personal wellbeing.

To further ensure robustness, we compared the male and female sequential models. This was done by applying an unconstrained model in which the parameters for males and females could be different, and a constrained model in which the structural and measurement weights were the same for males and females. The analysis was undertaken using both the male model, in which the parameter that links financial status with financial satisfaction was constrained to zero; and the female model, in which the parameter that links financial knowledge with financial satisfaction was constrained to zero. In both cases the unconstrained model provided a better fit to the data than the constrained model (female model: ∆χ2 [15] = 36.3, p < 0.003; male model: ∆χ2 [15] = 25.2, p < 0.05). The results indicated that there were gender differences in the parameter values, with a stronger link between financial status and financial satisfaction for females, and a stronger link between financial knowledge and financial satisfaction for males.

A final robustness check was undertaken to investigate whether partnered status modulates the gender specific sequential model relationships identified, (i.e., the differential role of financial status (female) and financial knowledge (male) with financial satisfaction). We ran an analysis dividing the dataset into four groups: female partnered [n = 142]; female non-partnered [n = 111]; male partnered [n = 187]; and male non-partnered [n = 65]. Given the sample size in each group, however, these results should be taken cautiously especially in the male non-partnered group. We fitted each of the previously identified best female and best male sequential models to each of these samples and then compared the BIC of each model in each sample. If partnered status does modulate the gender differences, then one of the female samples would be best fitted by the female sequential model, and the other by the male sequential model. Otherwise, both female samples would be best fitted by the female model. The same rationale applies to the male sample, with the proviso that the male non-partnered analysis is more speculative given the sample size.

In the female partnered sample the female sequential model fitted the data better than the male sequential model (BIC female model = 347.0 < BIC male model = 351.9). The best fitting parameters and critical ratios in the female sequential model are: Financial Knowledge—Financial Attitude = 0.53 (2.11); Financial Knowledge—Financial Behavior = 0.68 (3.49); Financial Behavior—Financial Status = 0.64 (3.38); Financial Status—Financial Satisfaction = 0.44 (3.92); Financial Satisfaction—Personal Wellbeing = 0.55 (7.45). In the female non-partnered sample the female sequential model also fitted the data better than the male sequential model (BIC female model = 312.2 < BIC male model = 316.6). The best fitting parameters (and critical ratios) in the female sequential model are the following: Financial Knowledge—Financial Attitude = 0.56 (1.00, not significant); Financial Knowledge—Financial Behavior = 0.61 (2.24); Financial Behavior—Financial Status = 1.00 (1.96); Financial Status—Financial Satisfaction = 0.37 (2.26); Financial Satisfaction—Personal Wellbeing = 0.61 (8.01).

In the male partnered sample the male sequential model fitted the data better than the female sequential model (BIC male model = 389.9 < BIC female model = 408.7). The best fitting parameters and critical ratios in the female sequential model are the following: Financial Knowledge—Financial Attitude = 0.88 (3.22); Financial Knowledge—Financial Behavior = 0.66 (2.69); Financial Knowledge—Financial Satisfaction = 0.43 (6.61); Financial Behavior—Financial Status = 0.8 (3.15); Financial Satisfaction—Personal Wellbeing = 0.49 (7.70). In the male non-partnered sample, however, the female sequential model fitted the data better than the male sequential model (BIC male model = 303.2 > BIC female model = 291.1). However, three out of five parameters were not significant. The best fitting parameters and critical ratios in the female sequential model are the following: Financial Knowledge—Financial Attitude = 0.79 (1.46, non-significant); Financial Knowledge—Financial Behavior = 0.94 (2.41); Financial Behavior—Financial Status = 0.37 (1.17, non-significant); Financial Status—Financial Satisfaction = −0.48 (1.28, non-significant); Financial Satisfaction—Personal Wellbeing = 0.55 (5.28).

This analysis suggests that in both partnered and non-partnered women financial satisfaction is strongly related to financial status, and not to financial knowledge. In the partnered male sample the relationship between financial knowledge and financial satisfaction is stronger than that of financial satisfaction and financial status. However, in the non-partnered male sample the relationship between financial satisfaction and financial status was stronger than that of financial satisfaction and financial knowledge (i.e., non-partnered men are more similar to women in this respect). However, the latter result is not robust since we had a very low number of participants in this sample.

Discussion

Joo (2008) proposed a model of financial wellness as a first step towards developing an overall measurement of financial wellness. The main characteristic of this model is that financial wellness comprises a number of subcomponents: financial status; financial satisfaction; financial knowledge; and financial attitudes. We implemented Joo’s model using a structural equation model, and applied it to a data set collected from 505 participants. All the estimates of the subcomponents were found to be significant, indicating some support for Joo’s concept of financial wellness as comprising subcomponents. Although the fit of this model was better than the one without subcomponents, its overall fit was poor. We therefore explored sequential models in which the subcomponents were causally related, and these provided a better overall fit with the data than the other two models. We also found that the best sequential model for males was different from the best sequential model for females.

Since the sequential models were the ones that best fitted the data, we have focused on them in this discussion. In both the male and female models, the only direct predictor of personal wellbeing was financial satisfaction. This concurs with previous studies which show a significant relationship between financial satisfaction and personal wellbeing (e.g., Graham and Petinato 2001; Hayo and Seifert 2003; Louis and Zhao 2002). This is also in line with Dolan et al.’s (2008) suggestion that the perception of financial circumstances (i.e., financial satisfaction), fully mediates the effects of objective circumstances (i.e., financial status) on personal wellbeing.

Financial satisfaction accounts for 33 % of the personal wellbeing variance in females and 26 % of this variance in males. This suggests that financial satisfaction is more important for females than for males with respect to personal wellbeing, and is probably related to the source of financial satisfaction. For females, the only direct predictor of financial satisfaction was financial status, accounting for a 16 % variance; whereas for males, the only direct predictor of financial satisfaction was financial knowledge, accounting for a variance of 11 %.

In accordance with the financial literacy literature, financial knowledge is a strong predictor of positive financial behavior, accounting for 55 % of its variance in males and 44 % in females. Financial knowledge is also a strong predictor of financial attitudes, accounting for 69 % of its variance in males and 30 % in females. These results also indicate that the role of financial knowledge is more important for males than for females. For males, financial knowledge is strongly related to financial behavior, financial attitude and financial satisfaction; whereas for females, the relationship between financial knowledge, financial behavior and financial attitudes is less strong. Moreover, as explained above, the model suggests no link between financial knowledge and financial satisfaction in females.

The relationship between financial knowledge and financial status is moderated by financial behavior. Financial behavior accounts for 69 and 64 % of the variance in financial status for males and females respectively.

Conclusion

Considerable resources are being directed towards improving levels of financial literacy with an expectation of improved financial decision making and quality of life. Demonstrating a link between financial literacy and quality of life is therefore a significant research objective with relevance for those supporting and designing financial literacy programs. This paper has identified such a relationship and the results also identify important differences in the relationship by gender which suggests areas of focus for improvements in program design.

Overall, the results support Joo’s (2008) concept of financial wellness as a multidimensional concept. Our advanced model—the sequential model—based on Joo’s concept of financial wellness, was developed to establish causal relationships between the subcomponents proposed by Joo; and paves the way for future research to test the model in different populations, with explicit control of other demographic characteristics. The sequential model of financial wellness could also be tested empirically to derive hypotheses.

Other interesting results emerged from our study: One corroborates previous research, while another requires further investigation. As in previous studies, the results provide favorable evidence of the role of financial literacy in financial behavior. They also indicate that financial knowledge (more than financial status) provides financial satisfaction for males, while financial status provides financial satisfaction for females. These results have the potential to inspire a host of interesting research questions.

The fact that women’s financial status has a strong impact on their financial satisfaction and in turn, on their personal wellbeing, may suggest that an increase in women’s participation in the labor market will improve their personal wellbeing. However, this is not straightforward, as other variables, unrelated to employment (e.g., financial status of partner), could also lead to increased financial status. Moreover, an increase in working hours leads to a decrease in leisure time, thereby potentially decreasing overall personal wellbeing. Future research that takes all these variables into account is worth pursuing. Unlike women, men’s financial satisfaction is affected more by their financial knowledge than by their financial status. This suggests that financial literacy programs may not only be important in influencing financial behavior, but may also be important for increasing males’ financial satisfaction.

Notes

Willis (2008) notes the first US conference in 1934 on consumer education.

In Australia the nomenclature of retirement savings is bound up in the catch-all phrase “superannuation” which is the tax advantaged vehicle for retirement savings. It can be thought of as a 401(k) plan with one notable difference, participation is mandatory. Employers are required to contribute 9 % of earnings on behalf of employees to an eligible superannuation fund. This rate will increase gradually to 12 % by 2019.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2011a), Education and Work, Australia, Cat. No. 6227.0, Canberra.

See Rigdon (1996) for the merit of each measure of index fit.

References

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 2009–2042. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.07.006.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2009). Australian Labour Market Statistics (No. 6105.0), Canberra, Australia.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2011a). Education and Work, Australia (No. 6227.0), Canberra, Australia.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2011b). Household Income and Income Distribution, Australia (No. 6523.0), Canberra, Australia.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2011c). Labour Force (No. 6202.0), Canberra, Australia.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012). 2011 Census—Employment, Income and Unpaid Work, Canberra, Australia.

Australian Securities and Investments Commission. (2011). National financial literacy strategy, Report 229. Sydney: Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

Christelis, D., Jappelli, T., & Padula, M. (2010). Cognitive abilities and portfolio choice. European Economic Review, 54, 18–39. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.04.001.

Commonwealth of Australia. (2008). Families in Australia: 2008. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Cummins, R. A. (1995). On the trail of the gold standard for life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 35(2), 179–200. doi:10.1007/BF01079026.

Cummins, R. A. (2000). Personal income and subjective wellbeing: A review. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(2), 133–158. doi:10.1023/A:1010079728426.

Cummins, R. A. (2010). Subjective wellbeing, homeostatically protected mood and depression: A synthesis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(1), 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10902-009-9167-0.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 94–122. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2007.09.001.

Graham, C., & Petinatto, S. (2001). Happiness, markets and democracy: Latin America in comparative perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2(3), 237–268. doi:10.1023/A:1011860027447.

Greninger, S. A., Hampton, V. L., Kitt, K. A., & Achacoso, J. A. (1996). Ratios and benchmarks for measuring the financial well-being of families and individuals. Financial Services Review, 5(1), 57–70.

Gutter, M., & Copur, Z. (2011). Financial behaviors and financial well-being of college students: Evidence from a national survey. Journal of Family Economic Issues, 32(4), 699–714. doi:10.1007/s10834-011-9255-2.

Hayo, B., & Seifert, W. (2003). Subjective economic well-being in Eastern Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24(3), 329–348. doi:10.1016/S0167-4870(02)00173-3.

Hilgert, M., Hogarth, J., & Beverly, S. (2003). Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 89, 309–322.

International Wellbeing Group. (2006). Personal wellbeing index (4th edn). Melbourne: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University. Retrieved September 11, 2012, from http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/instruments/wellbeing_index.htm.

Joo, S. (2008). Personal financial wellness. In J. J. Xiao (Ed.), Handbook of consumer research (pp. 21–33). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-75734-6_2.

Joo, S., & Grable, J. E. (2004). An exploratory framework of the determinants of financial satisfaction. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25(1), 25–50. doi:10.1023/B:JEEI.0000016722.37994.9f.

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (1999). Preface. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kim, J., & Garman, E. T. (2003). Financial stress and absenteeism: An empirically derived model. Financial Counseling and Planning, 14(1), 31–42.

Louis, V. V., & Zhao, S. (2002). Effects of family structure, family SES, and adulthood experiences on life satisfaction. Journal of Family Studies, 23(8), 986–1005.

Malone, K., Stewart, S. D., Wilson, J., & Korsching, P. K. (2010). Perceptions of financial well-being among American women in diverse families. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 31(1), 63–81. doi:10.1007/s10834-009-9176-5.

Prawitz, A. D., Garman, E. T., Sorhaindo, B., O’Neill, B., Kim, J., & Drentea, P. (2006). InCharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: Development, administration, and score interpretation. Financial Counseling and Planning, 17(1), 34–50.

Prawitz, A. D., Kalkowski, J. C., & Cohart, J. (2013). Responses to economic pressure by low-income families: Financial distress and hopefulness. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34(1), 29–40. doi:10.1007/s10834-012-9288-1.

Raferty, A. E. (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. In P. V. Marsden (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1995. Oxford: Blackwell.

Rigdon, E. E. (1996). CFI versus RMSEA: A comparison of two fit indexes for structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 3(4), 369–379.

SPSS Inc. (2009). Amos 18.0. SPSS missing values 17.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc.

Van Praag, B. M. S., Frijters, P., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2000). A structural model of well-being: With an application to German data. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper TI 2000-053/3. Retrieved May 11, 2012, from http://www.tinbergen.nl/uvatin/00053.pdf.

Van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2011a). Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(2), 449–472. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.006.

Van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2011b). Financial literacy and retirement planning in the Netherlands. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(4), 593–608. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2011.02.004.

Willis, L. E. (2008). Against financial literacy education. Iowa Law Review, 94, 197–285.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support of the Australian Research Council Linkage Grant—LP0991752, and research partners GESB and the Western Australian Police.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

Questions Used in the Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

Personal Wellbeing

The following questions ask how satisfied you feel, on a scale from 0 to 10. Zero means you feel completely dissatisfied. Ten means you feel completely satisfied. The middle of the scale is 5, which means you feel neutral; neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

-

1.

Thinking about your own life and personal circumstances, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole?

-

2.

How satisfied are you with your standard of living?

-

3.

How satisfied are you with your health?

-

4.

How satisfied are you with what you are achieving in life?

-

5.

How satisfied are you with your personal relationships?

-

6.

How satisfied are you with how safe you feel?

-

7.

How satisfied are you with feeling part of your community?

-

8.

How satisfied are you with your future security?

-

9.

How satisfied are you with your spirituality or religion?

Financial Wellbeing

Now I want to ask some questions about your sense of financial well-being.

-

1.

On a scale of 1 to 10 where one is “overwhelmingly stressed” and ten is “no stress at all,” what do you feel is the level of your financial stress today?

-

2.

On a scale of 1 to 10 where one is “completely dissatisfied” and ten is “completely satisfied,” how satisfied are you with your present financial situation?

-

3.

On a scale of 1 to 10 where one is “feel completely overwhelmed” and ten is “feel very comfortable,” how do you feel about your current financial situation?

-

4.

On a scale of 1 to 10 where one is “worry all the time” and ten is “never worry,” how often do you worry about being able to meet normal monthly living expenses?

-

5.

On a scale of 1 to 10 where one is “no confidence” and ten is “high confidence,” how confident are you that you could find the money to pay for a financial emergency that costs about twice your weekly income?

-

6.

On a scale of 1 to 10 where one is “all the time” and ten is “never,” how frequently do you find yourself just getting by financially and living from payslip to payslip?

Financial Status

-

1.

Which of the following best describes your total annual household income from all sources, including returns from investments, before tax?

$20,000 or less; $20,001 to $40,000; $40,001 to $60,000; $60,001 to $80,000; $80,001 to $100,000; $100,001 to $120,000; more than $120,000; don’t know.

-

2.

What is the total value of all your assets?

Less than $10,000; $10,000–$49,999; $50,000–$99,999; $100,000–$124,999; $125,000–$249,999; $250,000–$499,999; $500,000–$749,999; $750,000–$999,999; $1 million or more; don’t know.

-

3.

What is the total amount of all your debts?

Less than $10,000; $10,000–$49,999; $50,000–$99,999; $100,000–$124,999; $125,000–$249,999; $250,000–$499,999; $500,000–$749,999; $750,000–$999,999; $1 million or more; don’t know.

Financial Behavior

-

1.

Have you consulted any of the following people regarding your finances over the last 5 years?

An accountant, a mortgage broker, a stock broker, an insurance broker, a taxation specialist, a financial counsellor, a bank manager or bank employee, a financial planner or advisor, Centrelink financial information service officers, someone else, none of these.

-

2.

Have you identified a figure for how much per year you will need to live on when you retire?

-

3.

Yes, No.

Financial Attitudes

-

1.

In your opinion, how important is it for people like you to keep up to date with what is happening with financial matters generally, such as the economy and the financial services sector?

Very important, quite important, not very important, not at all important.

-

2.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements (on a scale of 1 to 5 where one is “disagree strongly” and five is “agree strongly”).

“I don’t think it really matters much about superannuation or planning and saving for retirement because the government will make up the gap.”

Financial Knowledge

Financial General Knowledge

-

1.

If the inflation rate is 5 % and the interest rate you get on your savings is 3 %, will your savings have at least as much buying power in a year’s time?

Yes, No, Don’t know.

-

2.

Please indicate whether you think each of the following is true or false about the Goods and Services Tax (GST). (True, False, Don’t know)

-

(a)

The national GST percentage rate is 10 %.

-

(b)

The federal government will deduct it from your pay.

-

(c)

You don’t have to pay the tax if your income is very low.

-

(d)

It makes things more expensive for you to buy. Which of the following is the best description of a budget?

An accounting spreadsheet, spending as little as you possibly can, a plan for what you earn and what you spend, knowing where all your money goes, don’t know.

-

(a)

-

4.

Which one of the following is the most accurate statement about fluctuations in market values?

Investments that fluctuate in value are not good in the long term, good investments are always increasing in value, short-term fluctuations in market value can be expected even with good investments, don’t know.

-

5.

Which one of the following would you recommend for an investment advertised as having a return well above market rates and no risk?

Consider it “too good to be true” and not invest, invest lightly and see how it goes before investing more heavily, invest heavily to maximise your return, don’t know, other—please specify.

Knowledge of Financial Products

-

1.

If someone is not able to make the repayments on a secured loan, is the organization that lent them the money allowed to sell the assets that were used as security for the loan?

Yes, No, Don’t know.

-

2.

Which of the following is generally considered to make you the most money over the next 15 to 20 years?

A savings account, a range of shares, a range of fixed interest investments, a cheque account, don’t know.

-

3.

Which of the following term deposits would pay the most interest in total, or would they pay the same amount of interest?

One-year term deposit at 7 % interest per annum paid at maturity, one-year term deposit at 7 % interest per annum paid quarterly back into the term deposit, they would pay the same amount of interest.

-

4.

As far as you know, is each of the following statements true or false?

-

(a)

The Australian Securities and Investment Commission checks the accuracy of all prospectuses lodged with it.

True, False, Don’t know.

-

(b)

If providers of professional advice about financial products may receive commissions as a result of their advice, they are required by law to disclose this to their clients.

True, False, Don’t know.

-

(c)

There is a cooling off period after taking out a new house and contents insurance policy during which time you can cancel the policy and have your premium fully refunded.

True, False, Don’t know.

-

(a)

Superannuation General Knowledge

Please indicate if you think the following statements about superannuation are true or false.

-

1.

“Employers are required by law to make superannuation payments on behalf of their employees.”

True, False, Don’t know.

-

2.

“Employees cannot make superannuation payments in addition to any payments made by their employers”.

True, False, Don’t know.

-

3.

Do you know which amount is closest to the payment rate of the government Aged Pension for a single person living alone?

$7,800 per year = $150 per week, $13,000 per year = $250 per week, $18,200 per year = $350 per week, $23,400 per year = $450 per week, Don’t know.

-

4.

As far as you know, is the Australian Aged Pension

-

(a)

Income tested?

Yes, No, Don’t know.

-

(b)

Asset tested?

Yes, No, Don’t know.

-

(a)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gerrans, P., Speelman, C. & Campitelli, G. The Relationship Between Personal Financial Wellness and Financial Wellbeing: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. J Fam Econ Iss 35, 145–160 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9358-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9358-z