Abstract

The theory of compensatory consumption suggests that a possible lack of traditional avenues for fulfilling needs for social status may lead ethnic minorities to shift measures of social status from traditional indicators such as occupational prestige to consumption indicators of status conveying goods. In this study we investigate whether a household’s ethnic identity affects its budget allocation to status conveying goods. Annual budget shares for apparel, housing, and home furnishings are used for measuring status consumption. Results show that Asian American households allocate more of their budget to housing, while African American more to apparel, compared to European households. Hispanic households allocate more of their budget to both apparel and housing than European American households, but to a lesser degree compared to Asian Americans to housing and African Americans to apparel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Material possessions are used to convey a variety of symbols, including status, by the people who own them (Solomon, 1983). Those goods and services that are consumed more for social display than for actual utility are defined as status conveying goods (Fan & Burton, 2002). People of all income levels and social classes have sought status through consumption (Bagwell & Bernheim, 1996). To function as status conveying goods/services, they must be either easily seen by or talked about with others, and must be accepted as symbols of status according to widely held social beliefs.

This research looks at whether a household’s ethnic identity, based on self-identification and defined as a collection of individuals who have similar phenotypical characteristics and identify with a distinct culture, affects its budget allocation to status conveying goods. Specifically, is there a difference in the household budget allocation to status conveying goods among European American, Asian American, Hispanic, and African American households? Why might we expect to see such differences? Since status conveying consumption is tied to the symbolic meanings of products in society, explanations of status-oriented consumption should take societal phenomenon into consideration (Mason, 1983; Venkatesh, 1995). The concept of compensatory consumption provides one such explanation.

Compensatory consumption occurs when socially prescribed avenues for fulfilling needs for social status are blocked. It is based on a “general lack of need-satisfaction” (Gronmo, 1988). As a result, an individual attempts to shift measures of social status and prestige from non-consumption to consumption characteristics. Originally constructed to explain the status conveying consumption patterns of working class European American men in occupational positions that lacked prospects for the future (Chinoy, 1952), the concept may also be useful in explaining the behavior of the members of other groups whose opportunities to achieve social status are restricted or blocked, including members of ethnic minorities.

Members of ethnic minorities face continuing difficulty in achieving social status based on occupational prestige and income. Even when these difficulties are overcome and some members of ethnic minorities achieve occupational and economic success, they still occupy relatively low positions in the ethnic hierarchy of American society. As a result, even when controlling for occupational status and income, members of ethnic minority groups may engage in more status conveying consumption than members of the white, European American majority.

Previous studies have outlined general differences in the expenditure patterns of various ethnic households in the United States (Fan, 1997, 1998; Fan & Lewis, 1999; Fan & Zuiker, 1998), but none have directly examined the specific effects of ethnic identity on household budget allocation to status conveying goods. This study, while unable to evaluate the process by which ethnic groups make status conveying consumption decisions, provides a first step in measuring the extent to which differences exist among ethnic groups with respect to status conveying consumption. The measure of such differences is the budget allocation to categories of goods that are likely to be status conveying.

Literature Review

Consumption

In looking at the use of consumption to convey social meaning, we must acknowledge that products are more than simple objects used only for utilitarian purposes (Richins, 1994). Products also carry with them social symbols and meaning that is conveyed to others when seen or talked about. The meaning and status attributed to material goods is an aspect of the socially constructed world (Solomon, 1983) and its norms and values, to the goods themselves by means of marketing and fashion (Dubios & Duquesne, 1993; McCracken, 1986; Schor, 1998).

Consumers are not always simply “buyers” looking to fulfill material needs, but “cultural beings” who arrive at consumption decisions based on a host of cultural and normative factors (Applebaum & Jordt, 1996), including the social conveyance of status. Most people care about their position in society and how their levels of success and status are perceived by others (Frank, 1985). Being seen as successful is important in fulfilling an individual’s self-actualization or self-esteem needs (Maslow, 1954), and consumers use material symbols to influence the perceptions of others in these areas.

In one of the first considerations of the conspicuous use of material goods to convey status, Adam Smith described the desire for objects that conveyed a level of opulence, rarity and costliness that only the owner could possess (Stankovic, 1986). The usefulness of these items was not considered, and the item’s desirability was enhanced by its costliness (Stankovic, 1986).

The concept and examination of status oriented, or conspicuous, consumption really began to take shape in the 1890’s with the work of Thorstein Veblen (1899) and his publication of Theory of the Leisure Class. Veblen delineated conspicuous consumption as the preference of consumers to pay a higher price for an equivalent good (Bagwell & Bernheim, 1996). These “Veblen effects,” when applied to consumption decisions, involve the symbolic conveyance of status when displayed by the owner. In this framework, material items have significant meaning when displayed to others (Gottdiener, 2000). Veblen adds that displays of status consumption are not limited to the wealthy. They are also found among members of “lower” social classes, trying to emulate the class above them (Trigg, 2001). In fact, these displays have become an increasingly middle/lower class phenomenon given the relative affluence Americans have experienced since the 1950’s (Mason, 1981). Central to Veblen’s ideas is the dichotomy in humans between self-serving pecuniary instincts and behavior that contributes to the social public (Dugger, 1988).

Several reasons for individuals to partake in conspicuous consumption have been suggested. Veblen outlines three “motives” for conspicuous consumption (Campbell, 1995); A person’s self-esteem is dependent on the opinion of others (social interaction theory), and the display of wealth increases the esteem held for the person by others (Gottdiener, 2000). Although many cultures have strict social segmentation based on set, immutable criteria, in societies where there is some mobility within and across social classes based at least to some extent on wealth, conspicuous consumption is also seen as a way for an individual to appear to have the appropriate characteristics to enter into social groups that provide social networks and business contacts, thus continuing the segmentation of a society (Jaramillo & Moizeau, 2003; Mason, 1981; van Kempen, 2003).

Satisfaction for individuals is derived from distancing themselves from the social class below them, and more closely allying with the social class above them. In their examination of Leibenstein’s (1950) “snob” and “bandwagon” effects under conspicuous consumption, Corneo and Olivier (1997) developed a model where distancing oneself from the poor and identifying oneself with the rich are two distinct motivations for consuming conspicuously.

Conspicuous consumption results in envy by others. Such consumption seeks to gain the esteem of others and improve others opinion of the conspicuous consumer. These “invidious comparisons” (Campbell, 1995) serve to propel emulation and therefore ownership.

Among the few studies that attempt to specifically identify goods that convey status, Chao and Schor (1998) identified lipstick as a status conveying commodity among women. They found that for lipstick, higher prices resulted in more consumption of the particular product, despite being equal in quality to lower priced products. In a more recent study, Fan and Burton (2002) identified specific goods that convey social status to others using a sample of university students. Within three categories of general purpose, car-related and house-related goods, they asked respondents to select from a list those items that they thought would give the impression of higher status. Among the commodities ranked by the student sample as conveying status were clothing, vacations, laptop computers, new bigger homes, and luxury cars. Among vehicle-specific commodities a fancy stereo system, sunroof/moonroof, leather interior, and four-wheel drive were identified as status conveying. And among housing-specific commodities students identified home furnishings, hardwood floor, a pool, a hot tub, central air, and a large lot.

A specific type of conspicuous consumption, compensatory consumption, is utilized when an individual consumes conspicuously to compensate for the lack of status in other aspects of life. While Veblen discusses conspicuous consumption by those not in the upper class as having emulatory motives, compensatory consumption is not necessarily an attempt to emulate those in a higher social class but rather an attempt to shift the measurement of status and success in one’s life from non-consumption characteristics, such as occupational prestige, to consumption characteristics. Gronmo (1988) defines compensatory consumption as a response to a general lack of psychological need-satisfaction by a consumer for whom more adequate need-satisfaction attainment is somehow unavailable. Through compensatory consumption, an individual attempts to rectify the lack of status and self-esteem. Compensatory consumption, as does all conspicuous consumption, involves both the desire to satisfy the need for self-respect, and the need for respect and feelings of equal status from others (Caplovitz, 1967).

The idea of compensatory consumption was initially applied to unemployed and blue-collar workers experiencing a lack of occupational opportunity in the socio-economic sphere (Chinoy, 1952; Jahoda, Lazarsfeld, & Zeisel, 1933; Lynd & Lynd, 1937). These studies found that to compensate for the lack of need-satisfaction in occupational advancement and social prestige, workers turned to placing increased importance on “irrational spending” and the acquisition of material possessions, including new appliances, home furnishings, homes, and automobiles.

Past studies emphasized that for workers with little chance of occupational advancement, life-style becomes the new measures of success, status, and esteem (Bell, 1960; Mills, 1951). Consumption activities could be an attempt to feel in control over their restricted occupational and social existence (Daun, 1983). Caplovitz (1967) proposed that because of this measure-shifting function of compensatory consumption, consumption was more significant for low-income households than for the traditional Veblenian “leisure class” household.

More recent studies by Woodruffe (1997, 1998) have investigated compensatory consumption as a means of handling “lacks” in areas other than occupation in an individual’s life. Study subjects identified specific instances where they have used compensatory consumption to overcome a lack of psychological need-satisfaction in marital and family satisfaction, personal appreciation by family and peers, personal happiness, self-esteem, control, confidence, loneliness, as well as a lack of financial resources. These studies show that compensatory consumption can be related to lacks in need-satisfaction in many areas of life and is not limited to the occupational sphere looked at by the initial research on compensatory consumption. As such, the additional marginalization and lack of opportunities for social accomplishment by consumers of color may be a factor in influencing their budget allocation and lead to an increase in spending on conspicuous goods for compensatory consumption purposes.

Ethnic Identity

If the utilization of compensatory consumption is based on the inability of consumers to attain social status through non-material avenues due to a poverty of opportunity, ethnicity and the continued structural marginalization of people of color in the United States should be looked at as a possible indicator in determining a household’s level of compensatory consumption. Blumer defined ethnic prejudice as “a sense of group position” (Lyman, 1984), and outlines ethnic relations as a process where people are categorized into a non-static set of hierarchal groups. Through stereotypes and attitudes, societal groups reproduce existing ethnic hierarchies (Hollander & Howard, 2000). This collective definition of ethnicity and the positions that ethnic groups hold is displayed in a variety of venues, including occupational opportunities, media representations, and leadership roles in politics and religion (Lal, 1995).

Ethnic hierarchies are created from the stereotypes of socially created ethnic groups and each group’s relative similarities/differences in values from the primary majority or power-holding group (Hagendoorn, 1993). Stereotypes and hierarchies are typically collectively shared by a society, and they result in a system of normative restraints where each group has a defined “position” (Hagendoorn, 1993) that establishes its occupational, educational, and social opportunities. These shared stereotypes include negative beliefs, such as cultural causes of ethnic group poverty among African Americans, and positive beliefs, such as the Asian American “model minority” work ethic. In her model of the legitimization of oppression, Wolf (1986) proposes that legitimization of hierarchical position stems from circumstances where the oppressed population(s) is in an environment that is both generative (individually) and supportive (structurally) of the oppression. The process includes habituation and socialization, which is achieved through the passage of time, and geographic and social isolation. Accommodation by the oppressed population must involve the lack of perceived alternatives of acceptable societal mobility for the population. Legitimization of the oppression of ethnic minorities in the United States involves the internalization by the individual, and by the society, of their position within the larger societal hierarchy.

These factors have contributed to the commonly held ethnic hierarchy in the United States, with European American power-holders on the top, followed by the Asian American, Hispanic, and African American groups. This hierarchical structure is supported by demographic data showing above-poverty rates, individual income, educational attainment, and occupational prestige highest at the top, and decreasing with each group in the hierarchy (U.S. Census Data, 2000). This stratification is also manifest in occupational opportunities. In a study looking at social inequality in the labor market, Lim (2000) found that employers ranked Asians as the best non-European American workers, Latinos (Hispanics) in the middle, and African Americans as the worst workers. The study also found that the labor markets represented by firms included in the study were extremely segmented, and that the ethnic identity and gender of the person holding a job previously was the significant indicator of the ethnic identity and gender of the person who would be hired next for the job, thus continuing the hierarchy and the lack of mobility for marginalized ethnic groups.

Although research on ethnic consumers has increased considerably since the early 1990’s (Geng, 2001), no studies have looked specifically at the issue of status consumption and ethnic identity. However, several studies have investigated general differences in consumption patterns among different ethnic groups. As early as the late 1940’s, and then again in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, several studies were conducted by marketers interested in targeting the African American consumer. These studies found that poor African American men were more likely to purchase a high-end auto than poor European American men (Ebony, 1949), and that poor African American men were more likely to purchase prestige goods than their European American counterparts (Bauer, Cunningham, & Wortzel, 1965). In a similar study, poor African American women were more likely to buy brand-name food than poor European American women (Stafford, Cox, & Higginbottom, 1971).

Expenditures by African American households have been shown to be different than those of European American consumers in several areas. Fan (1998) found that African American households allocated more of their household budget to food at home, household fuel and utilities, and tobacco. These higher expenditures are consistent with findings from other studies (Fan & Lewis, 1999; Paulin, 1998). Additional studies found higher consumption of personal care products (Humphreys, 2002; Wagner & Soberon-Ferrer, 1990), apparel (Fan & Lewis, 1999; Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998; Wagner & Soberon-Ferrer, 1990), and public transportation (Paulin, 1998), and lower budget allocation to health care (Fan, 1998; Fan & Lewis, 1999; Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998; Wagner & Soberon-Ferrer, 1990), entertainment (Fan, 1998; Fan & Lewis, 1999; Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998), and food away from home (Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998; Wagner & Soberon-Ferrer, 1990). These differences, particularly in the budget allocation for apparel and personal care products, support the possibility that African American consumers are engaging in compensatory consumption.

Hispanic households, as the largest growing minority population in the U.S., consume in different ways than European American households. Hispanic households resemble African American households in their relatively high spending on food and utilities compared to European American households (Fan, 1998; Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998), but Hispanic households also allocate a higher budget share to housing compared to European American households (Fan, 1998; Fan & Zuiker, 1998; Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998; Wagner & Soberon-Ferrer, 1990). In addition, consumption of apparel (Fan & Zuiker, 1998; Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998) is higher for Hispanic households than for European Americans. Lower levels of spending by Hispanic households were found for health care (Fan, 1998; Fan & Zuiker, 1998; Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998), tobacco (Fan, 1998; Fan & Zuiker, 1998; Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998), education (Fan & Zuiker, 1998; Humphreys, 2002), and entertainment (Fan & Zuiker, 1998; Humphreys, 2002; Paulin, 1998). The higher levels of budget allocation to two commodity categories that convey status (Fan & Burton, 2002), housing and apparel, may support higher levels of compensatory consumption among Hispanic households as compared to European American households.

Asian American spending has been less studied than that of African American or Hispanic populations, in part due to their relatively small population size in the U.S. Both Asian American and Pacific Islanders fall into this ethnic category. Asian American households allocate more of their budget to housing than any other ethnic group in the United States (Fan, 1998). Other consumption categories in which Asian households show higher levels of budget allocation include education and food away from home when compared to European American households (Fan, 1997, 1998), and on education, apparel, and transportation as compared to European Canadian households (Abdel-Ghany & Sharpe, 1997). Asian households allocate less of their budget to health care, fuel and utilities, transportation, and apparel than European American households, and to tobacco and alcohol, household operations, personal care, and recreation than European Canadian households (Abdel-Ghany & Sharpe, 1997). The higher level of budget allocation to housing may be a reflection of compensatory consumption among this group.

Conceptual Framework

For this study we apply the theory of compensatory consumption to ethnic differences in expenditure on status conveying goods. Compensatory consumption is the consumption of status conveying goods in a way that allows an individual experiencing a lack of non-commodity related status to measure status and esteem based on this conspicuous consumption. A clear path to non-commodity status elevation would include opportunity to obtain status and self-esteem through workplace and everyday social encounters (i.e., promotion, looked upon as equal). These motives would direct the individual’s actions to take advantage of any opportunity provided, therefore meeting status and self-esteem needs. Compensatory consumption theory suggests that if the motive to meet these needs is present, but there are insufficient opportunities to meet these needs, an individual will turn to the sphere of consumption to measure their success and status. This status elevation through compensatory consumption is inadequate in that although it does provide some level of status elevation, it does not provide an adequate, long-term solution to the lack of status need-satisfaction by people engaging in compensatory consumption (Gronmo, 1988).

Due to the persistence of ethnic/racial hierarchies as well as the individual and structural denial of opportunities in both the workplace and in larger society based on race, ethnic minority groups may experience a lack of status and self-esteem need-satisfaction, and may engage in compensatory consumption as a result, increasing their preference for status conveying goods.

Neoclassical consumer demand theory suggests that consumer expenditures on any goods, including status conveying goods, are determined by income, prices, and preferences. Compensatory consumption theory suggests that in the case of ethnic minorities, a desire to attain status through consumption may augment their preferences for status conveying goods over non-status conveying goods, and therefore increase their consumption of status conveying goods, ceteris paribus. Of course ethnicity can also affect status conveying goods in ways other than for compensatory needs. For example, cultural differences might lead a particular ethnic group to prefer a particular type of commodity over another. In addition, other preference shifters, such as age, family composition, and occupation also affect consumption of status conveying goods. This relationship between ethnicity and consumption of status conveying goods is depicted in Fig. 1. This conceptual framework suggests that ethnic minorities would spend relatively more on status conveying goods, compared to white, European Americans. Detailed hypotheses are presented in the next section after measurements are defined.

Data, Measurement, and Hypotheses

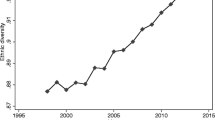

Data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX) were used for this analysis (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1996–2002). Gathered on an ongoing quarterly basis and consisting of a representative sample of civilian, non-institutionalized households in the United States, the CEX collects data on household expenditures and demographic characteristics. In order to gather sufficient sample sizes for minority ethnic groups, interview survey data from 1996–2001 were used. Households in which the reference person has indicated an ethnic identity of European American, African American, Asian American, or Hispanic are included. The total sample size is 25,472 households with all four quarters of expenditure data. Because households with very high income are likely to be outliers, we excluded those households with top-coded income, thus reducing the sample size to 24,198. Further deleting those in armed forces results in a final sample size of 24,099, of which 18,553 households are European American, 2,694 households are African American, 847 households are Asian American, and 2,005 households are Hispanic. Note we use both complete and incomplete income reporters because we utilize total expenditure data instead of income data in this study.

To operationalize the concept “status conveying consumption,” we turn to previous studies identifying status conveying goods (Chao & Schor, 1998; Fan & Burton, 2002). Because of data limitations we are not able to include all the commodities that have been identified by these previous studies. We choose three groups of commodities, apparel, housing, and home furnishings, to reflect different signaling ranges.

Apparel is chosen as a symbol of the compensatory consumption commodity measure to convey success to the community at large. Apparel signals status (or lack thereof) to peers and extended family, and to anyone an individual comes in contact with. This expenditure category includes budget allocation to apparel and footwear for all members of the household, and other apparel products and services.

Housing is chosen as a symbol of the compensatory consumption commodity measure to convey success to oneself, as well as to peers, neighbors, and extended family. Housing is more restrictive in its signaling range than apparel, as it only signals status to others who are close enough to the consumer to either know of the status level of the housing through personal conversation or be a neighbor or guest in the house. This expenditure category includes budget allocation to mortgage interest, property tax, and maintenance, repairs, insurance, and other expenses for households who own their homes, and rent payments for those who rent their homes.

Home furnishings are chosen as the third category of compensatory consumption commodity measure. Home furnishings is the most restrictive of the three commodity categories being examined, as the signaling of status through home furnishings requires others to be present inside the home. This expenditure category includes budget allocation to household textiles, home furnishings, floor coverings, major appliances, small appliances/miscellaneous house wares, and miscellaneous household equipment.

Based on the conceptual framework and our measurements of the concepts, the following hypotheses are formed:

-

H1: Asian American, Hispanic American, and African American households will each allocate more of their budget to apparel, housing, and home furnishings, compared to European American households, all things being equal.

-

H2: In accordance with the established social hierarchy in the U.S., African American households will have the highest budget allocation to status conveying goods within each of the apparel, housing, and home furnishings commodity categories, followed by Hispanic households, Asian American households, and European American households, in that order, all things being equal.

Income, prices, and other preference shifters are used as controls for this study. Total expenditure, as a proxy for permanent-income (Paulin, 1998), is used in the analysis. Inflation adjustments for all income and expenditure variables are made to bring all expenditure figures to 2,002 dollars using the overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) for each year. Prices are also affected by regional differences, therefore region of residence and population size are controlled to reflect these differences. Additional preference shifters are included based on previous research on ethnic differences in household budget allocation (Abdel-Ghany & Sharpe, 1997; Fan, 1998; Paulin, 1998). These control variables include (a) characteristics of the reference person such as age, educational attainment (coded as less than high school, high school/some college, Bachelor’s degree, or post graduate), occupation (coded as six occupational categories, not working, and retired), and self-employment status of the reference person, (b) characteristics of the household such as home ownership (coded as home owner with mortgage, home owner without mortgage, or renter), family composition (coded as number of adults, number of children, and number of earners), and family type (coded as married couple, single man headed families, single woman headed families, and other families), and (3) characteristics of the community such as population size (coded as >4 million, 1.20–4 million, .33–1.19 million, 125–329.9 thousand, and <125 thousand), and region (coded as urban Northeast, urban Midwest, urban South, urban West, and rural).

Analytical Methods

With our operationalization of the concepts, the conceptual framework in Fig. 1 can be represented by the following set of equations:

where W 1 = budget share to apparel, W 2 = budget share to housing, and W 3 = budget share to home furnishing. The dummy variables Asian, Hispanic, and African represent Asian–American, Hispanic American, and African American households, respectively. X j are control variables, including total expenditure and other demographic variables listed in the previous section.

Because household budget allocation to one category is likely to be correlated with household budget allocation to another category, the error terms of these three budget share equations are likely to be correlated. As such, Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) method is appropriate to obtain efficient coefficients. With the SUR method all three-budget share equations are estimated simultaneously. The SAS Proc Model procedure was used for this estimation.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive Analysis

Demographic profiles of each ethnic group are presented in Table 1. As the table illustrates, the mean total expenditure is the highest for the Asian American group, and lowest for the African American group, with the European American, and Hispanic groups in the middle. However, when the number of people in the household is taken into consideration, the European American group has the highest per capita total expenditure, followed by the Asian American group, then the African American group, and finally the Hispanic group. In addition, consistent with the ethnic hierarchy theory, per capita earning is also lower for Asian Americans than for European Americans.

The European American group is the oldest at a mean age of 51.5, and has the smallest number of people per household (2.51). They have the lowest level of non-employment (8.75%) and retirement (22.95%). European American households in the sample have the highest rate of homeownership (72.26%).

The Hispanic group is the youngest in the sample (43.7), has the lowest level of educational attainment, with over 44% of the group not obtaining a high school diploma. Hispanic households are the most likely to work in the farming/agriculture industry (1.9%). The majority of Hispanic households reside in either the urban south (36.06%) or the urban west (38.75%).

Finally, the African American group has the highest level of non-employment (17.78%). These households have the least number of earners (1.2) and the highest level of single women households (30.92%) in the sample. African American households are likely to live in urban areas in the South (50.37%). This group also has the lowest annual household expenditure ($26,687) and after tax income ($31,306).

T-tests are performed to determine if there are significant differences in the budget shares for apparel, housing, and home furnishing expenditures between the European American sample and the three other ethnic groups. Results of this analysis are presented in Table 2.

The t-test results in Table 2 show that there are some significant differences in budget allocation between the European American group and the other three ethnic groups in almost all of the comparisons. Exceptions include a lack of significance for apparel budget shares with the Asian American group, a lack of significance for home furnishing budget shares between any of the groups and the European American group. Although this analysis shows significant differences in the budget allocation to the three categories of expenditure among the ethnic groups, the t-tests do not take into account differences in household characteristics. Multivariate regression analysis controlling for other differences serve this purpose.

Multivariate Analysis

The corresponding R-Squared’s for each of the three commodity equations are .10 for apparel, .35 for housing, and .04 for home furnishing, respectively. Table 3 presents the results of the regression analysis and the t-tests. Results for the analysis on apparel, housing, and home furnishings budget share differences are discussed individually.

Apparel

Budget share for apparel is significantly higher for the Hispanic (.91% more) and African American (1.09% more) groups, but not significantly different for the Asian American group when compared to the European American group, ceteris paribus. Expressed in dollar values, the average difference is $283 annually for Hispanic households and $291 annually for African American households when compared to European American households. These findings are consistent with prior research and partially support hypothesis #1.

Hypothesis #2 is also partially supported by the data. Additional tests show that African American and Hispanic households do not allocate significantly different amounts to apparel from each other, but do have higher budget shares for apparel than the European and Asian American groups, other things equal. As the commodity category with the broadest visibility of the three tested in this study, apparel is tested as a conspicuous consumption category designed to convey status to the general population, including both well known and little known others. High levels of budget allocation in this category may be an attempt to compensate for more universal out-group social marginalization, encountered at a very general level and more prevalent for members of the African American and Hispanic groups based on their positions within the social hierarchy of the United States, rather than a desire to convey status to only to those relatively well known to the consumer.

Housing

Table 3 shows that on average, Asian American households spend 3.23% and Hispanic households 1.00% more of their budget on housing than European American households, ceteris paribus, partially supporting hypothesis #1. Expressed in dollar amount this is an average difference of $1313 annually for Asian American households and $311 annually for Hispanic households when compared to European American households. However, African American households do not have significantly different budget share for housing than the European American group, therefore not supporting the hypothesis that these households engage in status conveying consumption with increases in their budget share for housing. This finding does not support hypothesis #2 for this expenditure category and is an almost complete reversal of the hypothesized ranking of ethnic groups.

Housing is used in this analysis as a measure of the level of status conveying consumption to oneself, to immediate and extended family, neighbors, and to others who are well enough known to either have discussed about or been guests at the consumer’s home. This level of status conveyance may have important implications for specific groups, particularly for relatively new immigrant groups, such as the Asian American and Hispanic populations. These groups, due to the emphasis on close extended family relationships and the importance placed on respect within families (Fan, 1997; Fan & Zuiker, 1998; Fost, 1990; Maher, 1986), may choose to channel compensatory consumption behaviors into housing, in order to signal status to family and better known others such as family and friends in the home country, rather than other commodity categories. This may also be the result of a timeline effect, where new immigrant groups value the status conveyance of housing as a first step in showing their successful transition to the new country. This continued immigration situation tend to not be the case for the African American group, consistent with the current findings that there is no significant difference in African American and European American budget allocation. Housing expenditure is a somewhat unique commodity category in that it includes an economic investment component as well (Fost, 1990; Maher, 1986). Although only expenditure to mortgage interest, property tax, and maintenance expenses are used in the calculation of housing expenditure for homeowners in this study, the portion of the expenditure related to consumption and the portion related to savings are difficult to differentiate. In considering the extremely high levels of budget allocation to housing by Asian American families, an analysis of differences in the saving behavior of the four ethnic groups in the sample is conducted. A simple measure of savings is created using the difference between a household’s total income and total expenditure. This new savings variable is analyzed using the same model as the three expenditure categories. Consistent with other research (Fan, 1997) this analysis shows that Asian American households in our sample do in fact have the highest levels of savings of the four groups, other things equal. This possible preference for saving and the perception of housing as saving as well as consumption may contribute to the large budget share for this category among Asian American households.

Home Furnishing

Table 3 shows that budget share for home furnishing is not significantly different for the Hispanic group, and significantly lower, .35% and .39%, respectively, for the African American and Asian American groups when compared to the European American group, ceteris paribus. These findings are in contradiction to both hypothesis #1 and hypothesis #2.

The home furnishing category is selected as a reflection of the household’s desire to signal status in a very close, internal manner. Home furnishing, as it is limited to the family members living in the home and close friends or extended family, has very limited signaling capabilities. Because of this limited signaling sphere, ethnic minority households may chose to allocate less of their budget to this conspicuous consumption category, and more to more visible categories such as apparel and housing than their European counterparts.

These results show that households in ethnic minority groups allocate more of their budget to some status conveying consumption commodities, possibly due to the effects of compensatory consumption. While Asian Americans may use housing as a status signal, African Americans are more likely to use apparel to convey status. Hispanics are in the middle of these two groups, allocating budget to both housing and apparel to signal status but to a lesser extent. These results make sense in the context of budget constraints, as one cannot allocate more money to everything and thus has to pick and choose. What these groups choose to convey status, however, may be the result of differences in cultural and historical background. As different ethnic groups face different social circumstances and hold different cultural ideals, values, and norms, it seems reasonable to assume that we would find groups signaling to differing audiences, and therefore utilizing differing commodity categories to convey status.

While these results are consistent with some of our hypotheses, it does not mean these results can rule out other motivations for ethnic minority groups to spend more on some of the status conveying commodity categories. The obvious candidate is a cultural preference for certain commodities that may not be related to compensatory consumption. One possible way to study this issue is to compare expenditure patterns of ethnic minority groups with the expenditure patterns of their counterparts living in Asia, in Spanish speaking countries, and in Africa. However, due to very different price structures in these countries, a simple study of budget comparison is not sufficient to answer this question. Methodologies need to be developed for further study of this topic.

In addition, this study fails to ascertain whether the additional budget share for these status conveying categories is the result of the higher prices paid by these ethnic minority households, or the desire to conspicuously consume. Although regional and population size differences are controlled for, consumer racism and the corresponding higher prices paid by ethnic minority consumers may be influencing the budget allocation to particular commodity categories, including those that convey status. This issue is of particular concern for expenditure on housing, as housing market is quite localized and housing prices vary significantly by location. However, in order to address this issue detailed price data need to be obtained for consumers, something that is beyond the scope of the current study, but maybe doable with additional data.

Conclusion and Implications

The purpose of this study is to analyze the differences in status conveying consumption by Asian American, Hispanic, and African American households compared with European American households. To examine different degrees of status conveying consumption, budget share in three categories are examined: apparel, housing, and home furnishings. Findings suggest that Asian Americans allocate more of their budget to housing, African Americans allocate more of their budget to apparel, and Hispanics allocate more of their budget to both housing and apparel, but to a lesser extent than Asian Americans with respect to housing and African Americans with respect to apparel.

With the huge increase in the population of ethnic minorities, American society is becoming increasingly interested in cultural/ethnic issues. There is a general popular interest in the economic behavior of ethnic groups because the understanding of such behavior provides further insight into ethnic diversity. Increased understanding may therefore lead to greater acceptance of ethnic minority populations and reduce the marginalization they experience. At the practical front, people who work with ethnic minorities should be alerted to possible spending differences in status conveying goods that are deeply rooted in ethnicity. With such understanding the ethnic minority communities may be served better by government agencies and the private sector as well.

Although this study sheds some light on the conspicuous consumption expenditure of different ethnic groups, it has some significant limitations. Due to sample limitations, ethnic identity was categorized in four large groups. With the increasing growth in both numbers and diversity of ethnic minority households, large ethnic identity categories, such as Asian American or Hispanic may contain very dissimilar households within the groups, thereby grouping differently behaving households together and failing to capture more subtle differences. Furthermore, this study analyzed only three of a potentially large number of conspicuous consumption expenditure categories, possibly failing to consider other important categories, such as automobiles, due to data difficulties. It is also important to note that these three expenditure categories studied do have a utilitarian component as well, in addition to a status conveying component. We would also like to acknowledge the fact that fact that use of out-of-pocket expenditures is an imperfect measure of the status conveying properties of goods that have some durability component because the purchase or non-purchase of an item today may be directly related to the fact that the household still have some of the same or similar goods at home. Also, given the aggregate nature of these expenditure categories, we are not able to study expenditures on specific item such as designer clothing.

Given this study has shown that significant differences in household budget allocation to status conveying goods do exist among households differing in ethnic identities, this study extends the literature on conditions that are conducive to the consumption of status conveying goods. Further academic research can begin to investigate the intent and purpose of such consumption within a sociological framework, utilizing many different categories of status conveying consumption expenditure.

References

Abdel-Ghany, M., & Sharpe, D. L. (1997). Consumption patterns among ethnic groups in Canada. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics, 21, 215–223.

Applebaum, K., & Jordt, I. (1996). Notes toward an application of McCracken’s “Cultural Categories” for cross-cultural consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 23, 204–218.

Bagwell, L. S., & Bernheim, B. D. (1996). Veblen effects in a theory of conspicuous consumption. The American Economic Review, 86(3), 349–373.

Bauer, R. A., Cunningham, S. M., & Wortzel, L. (1965). The marketing dilemma of negroes. In C. H. Nightingale (Ed.), One the edge: A history of poor black children and their American dreams. New York: Basic Books.

Bell, D. (1960). The cultural contradictions in capitalism. New York: Basic Books.

Campbell, C. (1995). Conspicuous confusion? A critique of Veblen’s theory of conspicuous consumption. Sociological Theory, 13(1), 37–47.

Caplovitz, D. (1967). The poor pay more. Toronto: Collier-Macmillan.

Chao, A., & Schor, J. B. (1998). Empirical tests of status consumption: evidence from women’s cosmetics. Journal of Economic Psychology, 19(1), 1–30.

Chinoy, E. (1952). The tradition of opportunity and the aspirations of automobile workers. The American Journal of Sociology, 57(5), 453–459.

Corneo, G., & Olivier, J. (1997). Conspicuous consumption, snobbism and conformism. Journal of Public Economics, 66, 55–71.

Daun, A. (1983). The materialistic life-style: Some socio-psychological aspects. In L. Uusitalo (Ed.), Consumer behavior and environmental quality (pp. 6–16). Hampshire: Gower.

Dubios, B., & Duquesne, P. (1993). The market for luxury goods: Income versus culture. European Journal of Marketing, 23(1), 35–44.

Dugger, W. M. (1988). A research agenda for institutional economics. Journal of Economic Issues, 22(4), 983–1002.

Ebony, September (1949). Why negroes buy cadillacs p. 34. In C. H. Nightingale (Ed.), One the edge: A history of poor black children and their American dreams. New York: Basic Books.

Fan, J. X. (1997). Expenditure patterns of Asian Americans: Evidence from the U.S. Consumer Expenditure Survey, 1980–1992. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 25(4), 339–368.

Fan, J. X. (1998). Ethnic differences in household expenditure patterns. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 26(4), 371–400.

Fan, J. X., & Burton, J. R. (2002). Students’ perception of status-conveying goods. Financial Counseling and Planning Education, 13(1), 35–46.

Fan, J. X., & Lewis, J. K. (1999). Budget allocation patterns of African Americans. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 33(1), 134–164.

Fan, J. X., & Zuiker, V. S, (1998). A comparison of household budget allocation patterns between Hispanic Americans and non-Hispanic White Americans. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 19(2), 151–172.

Fost, D. (1990). California’s Asian market. American Demographics, 12(10), 34–37.

Frank, R. H. (1985). Choosing the right pond: Human behavior and the quest for status. New York: Oxford University Press.

Geng, C. (2001). Marketing to ethnic consumers: A historical journey (1932–1997). Journal of Macromarketing, 21(1), 23–32.

Gottdiener, M. (2000). Approaches to consumption: Classical and contemporary perspectives. In New forms of consumption: Consumers, culture & commodification (pp. 3–32). Oxford, England: Rowman & Littlefield; Cumnor Hill.

Gronmo, S. (1988). Compensatory consumer behavior: Elements of a critical sociology of consumption. In P. Otnes (Ed.), The sociology of consumption (pp. 65–85). New Jersey: Humanities Press International.

Hagendoorn, L. (1993). Ethnic categorization and outgroup exclusion: Cultural values and social stereotypes in the construction of social hierarchies. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 16(1), 26–51.

Hollander, J. A., & Howard, J. A. (2000). Social psychological theories in social inequalities. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 338–351.

Humphreys, J. M. (2002). The muliticultural economy 2002: Minority buying power in the new century. Georgia Business and Economic Conditions, 8(2).

Jahoda, M., Lazarsfeld, P. F., & Zeisel, H. (1933). Die arbeitslosen von marienthal. In S. Gronmo, Compensatory consumer behavior: Elements of a critical sociology of consumption. In P. Otnes (Ed.), The sociology of consumption (pp. 65–85). New Jersey: Humanities Press International.

Jaramillo, F., & Moizeau, F. (2003). Conspicuous consumption and social segmentation. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 5(1), 1–24.

Lal, B. B. (1995). Symbolic interaction theories. The American Behavioral Scientist, 38, 421–441.

Leibenstein, H. (1950). Bandwagon, snob and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers’ demand. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 64, 183–207.

Lim, N. (2000). Employers’ attitudes, social division of labor, and human resource practices in hiring low-skilled workers. Dissertation Abstracts International, A: The Humanities and Social Sciences, 61, 2.

Lyman, S. M. (1984). Interactionism and the study of race relations at the macro-sociological level: The contribution of Herbert Blumer. Symbolic Interaction, 7(1), 107–120.

Lynd, R. S., & Lynd, H. M. (1937). Middletown in transition. A study in cultural conflicts. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Maher, T. M. (1986). Met life focusing on Asian Americans. National Underwriter, 90(14), 4–8.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Mason, R. (1981). Conspicuous consumption: A study of exceptional consumer behavior. Hampshire, England: Gower Publishing Company Ltd.

Mason, R. S. (1983). The economic theory of conspicuous consumption. International Journal of Social Economics, 1(3), 3–17.

McCracken, G. (1986). Culture and consumption: A theoretical account of the structure and movement of the cultural meaning of consumer goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 71–84.

Mills, C. W. (1951). White Collar. The American Middle Classes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Paulin, G. D. (1998). A growing market: Expenditures by Hispanic consumers. Monthly Labor Review, March, 3–21.

Richins, M. L. (1994). Valuing things: The public and private meaning of possessions. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 504–521.

Schor, J. B. (1998). The overspent American: Upscaling, downshifting, and the new consumer. New York: Basic Books.

Solomon, M. R. (1983). The role of products as social stimuli: A symbolic interactionism perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 10, 319–329.

Stafford, J. E., Cox, K. K., & Higginbottom, J. B. (1971). Some consumption pattern differences between urban Whites and Negroes. In C. H. Nightingale (Ed.), One the edge: A history of poor black children and their American dreams. New York: Basic Books.

Stankovic, F. (1986). The relevance of the phenomenon of “Conspicuous Consumption” for the general theory of consumption. Economic Analysis and Worker’s Management, 4, 375–383.

Trigg, A. B. (2001). Veblen, Bourdieu, and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Economic Issues, 25(1), 99–116.

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000. CPS annual demographic supplement. .

van Kempen, L. (2003). Fooling the eye of the beholder: Deceptive status signaling among the poor in developing countries. Journal of International Development, 15(2), 157–177.

Veblen, T. (1899). Theory of the leisure class. New York: The New American Library.

Venkatesh, A. (1995). Ethnoconsumerism: A new paradigm to study cultural and cross-cultural consumer behavior. In A. Costa, & G. Bamossey (Eds.), Marketing in a multicultural world: Ethnicity, nationalism and cultural identity (pp. 26–67). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Wagner, J., & Soberon-Ferrer, H. (1990). The effect of ethnicity on selected household expenditures. Social Science Journal, 27(2), 181–199.

Wolf, C. (1986). Legitimization of oppression: Response and reflexivity. Symbolic Interaction, 9(2), 217–234.

Woodruffe, H. R. (1997). Compensatory consumption: Why women go shopping when they’re fed up and other stories. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 15(7), 325–337.

Woodruffe-Burton, H. (1998). Private desires, public display: Consumption, postmodernism and fashion’s “new man”. International Journal of Retailing and Distribution Management, 26(8), 301–313.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Robert N. Mayer and Dr. Armando Solorzano, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fontes, A., Fan, J.X. The Effects of Ethnic Identity on Household Budget Allocation to Status Conveying Goods. J Fam Econ Iss 27, 643–663 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-006-9031-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-006-9031-x