ABSTRACT

The purposes of the present study were to: (1) examine connections between performance success and the boundaries between families and the businesses they own and (2) explore whether boundary-performance links were mediated by satisfaction. Tests of the mediation hypothesis revealed that family satisfaction partially mediated connections between boundaries and family functioning. Business satisfaction fully mediated connections between boundary characteristics and business strengths, but did not mediate the relationship between boundary characteristics and cash flow problems. Although previous literature suggests that permeable boundaries (i.e. enmeshment) are especially problematic for family firms, this appears to be only partially true.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A common thread found in much of the literature on family firms is what will be collectively referred to in this paper as the boundary hypothesis. Structural family therapy, which is based on systems theory, suggests that boundaries regulate the closeness and proximity between systems (Minuchin, 1974). The same idea is a building block for much of the literature and emerging theories on family businesses. The boundary hypothesis suggests that many of the unique challenges facing family owned firms flow from the overlap between the systems that comprise them and that the boundaries between the systems function to regulate that overlap (e.g. Bork, Jaffe, Lane, Dashew, & Heisler, 1996; Davis & Stern, 1996). Based on anecdotal evidence, family business researchers and consultants have also suggested that extremes along the boundary continuum (which Minuchin describes as being either rigid or diffuse) may be associated with adverse consequences for family business owners (e.g. Davis & Stern, 1996; Marshack, 1998). Applied to the family firm, a diffuse boundary might suggest family dynamics inappropriately encroaching on the running of the business. A rigid boundary might suggest a “Berlin Wall” that deprives the business of the family’s positive values. In contrast, Aldrich and Cliff (2003) argue that family and business should be viewed as inextricably entwined and studied together.

Although much of the literature on family businesses discusses the role of extreme boundaries, systems theorists in the family domain have proposed that satisfaction with family boundaries may mediate the relationship between boundaries and various family outcomes (e.g. Olson & Wilson, 1992). Therefore, while extreme boundaries may perpetuate adverse consequences in some instances, subjective expectations regarding boundaries may ameliorate those consequences in others (Masuo, Fong, Yanagida, & Cabal, 2001). Despite their prominence, a review of the family business literature revealed no direct tests of these ideas about boundaries. Clearly, an empirical understanding of the relationship between boundaries, satisfaction, and the performance of both the business and the family is of significant practical and theoretical importance.

Boundaries and Family Businesses

Minuchin (1974) suggested that ideal family functioning occurs when boundaries are clear, permitting a balance of connection and autonomy. “Like the membrane of a cell, boundaries need to be strong enough to protect the healthy development” of the system while still allowing a constant flow in and out of that system (Colapinto, 1991). Applying these ideas to the family firm, Bork and colleagues (1996) suggest that one of the keys to family business success is the establishment of clear boundaries. By establishing clear boundaries, the authors suggest that families may learn to differentiate between family and business sub-systems.

A small body of literature on the use of resources by family businesses offers good reasons for clear financial boundaries between the systems. For example, household financial assets are more often used to support the business than the reverse, placing disproportionate financial burdens on family members (e.g. Haynes, Walker, Rowe, & Hong, 1999). Families often provide both paid and unpaid workers to their businesses who may or may not be the best-qualified individuals for the positions, thus impeding the financial success of the business.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that consultants working with families in business suggest that they should strengthen not just the financial but also the social and interpersonal boundaries between the subsystems (e.g. Marshack, 1998; Rosenblatt, de Mik, Anderson, & Johnson, 1985). This practice seems to move the family business more toward the disengaged side of the continuum. For instance, Rosenblatt and colleagues suggest that consultants may want to help family members see the benefits of establishing an office outside the home or observing strict rules about the use of a home-based office, or only discussing business issues at work and family issues at home. Marshack (1998) describes a “healthy” system as one with firm boundaries, where family members never talk about work at home and discuss business issues only at the office. Little attention is given to the possibility that some families may desire or thrive on more fluid interpersonal boundaries, freely discussing home and work issues throughout the day no matter what the location.

As mentioned above, family business literature seems to advocate rigid boundaries, keeping the two systems as separate as possible in order to avoid the possibility that family problems will affect business performance at some point in the future (Weigel & Ballard-Reisch, 1997). Most of this literature stems from work with family firm owners to resolve issues which have arisen in family firms such as nepotism, family members who take advantage of their employment in the firm, and management transition or ownership transfer (commonly referred to as “succession”). In contrast, work-life researchers, who focus on the perspectives of employees rather than owners, have long argued that greater flexibility on the part of business is needed in order for employees to balance their sometimes conflicting work and family responsibilities. Work-life scholars have advocated a variety of flexible boundary strategies including flex time, job-sharing, child-care, and family leave as possible means to enable employees to manage their family responsibilities as well as contribute effectively to their jobs (Roehling, Roehling, & Moen, 2001).

One primary difference in these two bodies of literature is the underlying fact that owners have business property that has value, while employees generally do not own part of the company in which they work. Obviously business property adds complications when it comes to ownership and succession. However, from an owner’s viewpoint, is there a difference in the success of the business or the family when boundaries are rigid compared to when they are permeable or diffuse?

The present study elucidates these issues by examining the relationship between boundaries and system performance in both the business and the family systems. Satisfaction will also be examined for its potential as a mediating variable in these relationships. In addition, because there are very few assessment tools designed specifically for use with family businesses, several instruments that were designed for families and have established reliability and validity will be adapted for use in the current study. Doing so should contribute to the field by offering a preliminary test of their utility in the field of family business research and consultation.

Boundaries

The goals and objectives of the family and the business systems are generally quite different (Weigel & Ballard-Reisch, 1997). Problems often arise when these objectives conflict and are forced into competition with one another. Following this logic, these objectives may become intermingled when ambiguity characterizes the boundaries that separate the family and the business. In fact, at least one author has suggested that one of the most common problems for family firms is the establishment of boundaries that are too diffuse, resulting in the enmeshment of the systems (Bork et al., 1996).

Diffuse Boundaries: Enmeshment

When boundaries are diffuse, systems become enmeshed and their respective needs and values become difficult to distinguish (Minuchin, 1974). For families that own or manage businesses, this may result in business decisions that are made in accordance with what is perceived as best for the family or vice versa. Probably the most commonly observed application of this is nepotism (Vinton, 1998). For instance, when family values guide business practices, parents may bring their children into the business and, without intending to, create career opportunities for their adult children for which they would not have qualified in the open market or might not otherwise have chosen for themselves.

The consequences of enmeshment can also be seen when conflicts carry over from one system to the other. For example, an argument between family members at home in the morning may permeate the entire workday. Other employees or family members may pick up on the tension and feel obligated to pick sides, act as if nothing is wrong, or try to smooth over the conflict (Kaslow & Kaslow, 1992). Diffuse boundaries may result in an unpleasant work environment in which private matters become public and interfere with business matters. Alternatively, if work-related disputes are carried over into the family system, the caring and mutual respect that may have led these individuals to go into business together can slowly erode, with “family feuds” erupting as a result (Kaslow & Kaslow, 1992). Therefore, when boundaries are diffuse, the needs and objectives of the two systems may become inextricably intertwined.

Rigid Boundaries: Disengagement

Although anecdotal evidence suggests that diffuse boundaries are more common than their opposite counterpart, problems can also emerge when the boundaries separating the systems become too rigid (e.g. Davis & Stern, 1996). As a result, business decisions may be based almost entirely on the best interests of the firm and family decisions made without regard to the business. Each system becomes primarily concerned with its own wants and needs (Minuchin, 1974). Conflict may emerge when those needs are treated as though they are in competition with one another. For instance, family members in a family business that adheres rigidly to policies regarding work schedules and vacations may feel qualities such as flexibility are all but lost.

Differentiation

Without clear boundaries, two systems can become enmeshed. If driven too far into separation, however, they might become disengaged. When appropriately clear boundaries are established, differentiation can occur. Differentiation, the cornerstone of Murray Bowen’s theory of therapy, is a process of separating oneself from one’s family (paradoxically while remaining connected) and developing an autonomous identity (Bowen, 1978; Kerr & Bowen, 1988). Kerr and Bowen (1988) have defined differentiation as the interplay between togetherness and individuality. The process of differentiation therefore creates a balance in which togetherness and separateness can exist in harmony with one another (Kerr & Bowen, 1988; Wiseman, 1996). It allows individuals the “freedom to agree, disagree, or just think differently” (Rosenblatt et al., 1985, p. 49).

When applied to the family firm, differentiation describes the ability of an individual to define his or her own life goals and values apart from the business. Further, it is the ability to say “no” to the business while still staying connected to it (Wiseman, 1996). Several researchers have suggested that the process of differentiation may be more difficult for members of a family firm than it is for individuals whose vocations are distinct from the family because of the overlap or enmeshment between the two systems (Kepner, 1983; Swogger, Johnson, & Post, 1988).

When enmeshment occurs, family members may feel a great deal of “togetherness pressure” from the family and the business, which they may find difficult to balance with the individual needs of their personal subsystem. In a typical business, individual employees answer to their supervisors and leave their work at the office when returning home. In some family firms, however, employees are not only answering to their supervisor but simultaneously to their parents, spouses, or other family members. Disappointment at work can permeate the household. Consequently, members of the business may perceive more pressure to perform and succeed. Because of this, they may care enormously about the thoughts, opinions, actions, or well being of those people with whom they live and work. In the process, they may neglect their own needs or fail to distinguish them from the needs of others.

When boundaries are characterized by rigidity, family members may, on the other hand, become preoccupied with their own wants and needs. Within these systems, the threshold for stress is enormous and a great deal is often required before members mobilize mutual support for one another. Because of this, family members may feel isolated and alone (Minuchin, 1974). In contrast to diffuse and rigid boundaries, clear boundaries have obvious intuitive advantages for family businesses. In short, by promoting differentiation, they may thwart many of the potential sources of conflict seen in these firms.

Work-to-Home and Home-to-Work Conflict

Huang, Hammer, Neal, & Perrin (2004) examined work-to-home and home-to-work conflict among couples where at least one family member worked full time, they had children at home and they were providing elder care. They utilized the definition of conflict proposed by Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek and Rosenthal (1964), the “simultaneous occurrence of two or more sets of pressures such that compliance with one would make more difficult compliance with the other” (p. 19). Job-family conflict was cited as a source of stress that could have negative effects on either home or job, or both. The results of this stress would appear in the form of absenteeism, lateness to work, intention to quit one’s job, and poor work performance. One of the conclusions the authors drew from their study was that organization supports that decrease home-to-work conflict will have benefits for family life in the form of less family distress and more family satisfaction. Further, efforts to decrease work-to-family conflict will have the benefit of decreasing home-to-work conflict over time. Our broad interpretation of these conclusions is that boundaries that are permeable may benefit both the business and the family, reduce conflict, increase satisfaction and reduce stress.

Missing Links

The boundary construct has not been operationalized within the family firm literature or the consultation field, there are no known measures designed to assess this potentially significant component of family businesses. The lack of investigation of the boundary hypothesis represents a fundamental void in the literature. In addition, although satisfaction has been hypothesized to be a mediating variable in the relationship between boundaries and family functioning (Olson & Wilson, 1992), this concept has not been explored in the family business literature. An investigation of the presence and impact of the boundary construct and its relationship to satisfaction and functioning in the family firm is warranted. A diagram of the relationships to be tested appears in Figure 1.

Methods

The data for this project were collected as part of a study of 187 family businesses in a Midwestern state. The interdisciplinary research team was composed of faculty and staff with backgrounds and expertise in the study of the various systems that comprise the family firm. In its entirety, data collection for the research project was divided into three phases. For each phase, a questionnaire was mailed to potential family business owners throughout the state. These phases were designed to assess the business, the family, and the interaction of the business and the family, respectively.

Measures

All but one of the family measures used in this study consisted of well-established subscales containing multiple items. Since these measures are among the widely used and well-validated indicators of systems functioning in the family literature (Fischer & Corcoran, 1994; Olson, 1999) and tap generic systems dimensions like “cohesion” and “adaptability” (Olson et al., 1989) it seemed reasonable that they would also be applicable to the functioning of family business systems. (See Table 1 for a direct comparison of sample items). Business items were examined by all members of the research team to make sure that they were parallel in meaning to the family items. Although the family business measures, adapted from the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale and related family assessment instruments, are new to this study. However, since they directly parallel the family scale items, and center on well-validated generic systems properties, a case can be made for their face and content validity. While construct validity will only be established through future research, the fact that these adapted scales are internally consistent (see Table 2) is encouraging. A limitation of this study, which is typical of much family research (Fisher, 1982), is that systemic properties are based on the perception of one individual respondent.

All items used a Likert answer format with five answer options. Cronbach’s alphas for multi-item scales all were acceptable, ranging from .78 to .95. Table 2 summarizes information about all measures. For all multi-item scales, mean scores were used for subsequent analyses.

Individual boundaries were measured by 10 items from the 1997 National Study of the Changing Workforce, divided into two subscales (Bond, Galinsky, & Swanberg, 1998). The first subscale, labeled work-to-home negative spillover, was composed of five items designed to assess the frequency with which the business has a negative impact on the respondent’s personal life. The second subscale, home-to-work negative spillover, consisted of five items designed to assess the frequency with which respondents reported their families or personal lives negatively affected their job productivity. For both subscales, high scores suggested more permeable boundaries.

Family boundaries were assessed by the 12 items that make up the family cohesion subscale of FACES IV (Olson, Tiesel, Gorall, & Fitterer, 1996). This subscale is further divided into two sets of six items written to assess the extremes of enmeshment and disengagement within the family. Conceptually, enmeshment can be thought of as the outcome of permeable boundaries whereas disengagement is the outcome of those that are rigid. Answer options ranged from “does not describe our family at all” to “describes our family very well.” High scores indicated permeable or rigid boundaries, respectively for enmeshment and disengagement.

Business boundaries were adapted from the 12 items that make up the family cohesion subscale of FACES IV. Each item from the family cohesion subscale was reworded to reflect cohesion within the family business. Both scales were suggestive of within-system boundaries such that high scores on the enmeshed and disengaged scales indicated diffuse and rigid boundaries within the business system. The business boundary subscales were scored in the same manner as the family boundary subscales.

Family satisfaction was operationalized using the family satisfaction scale from the Family Assessment Package (Olson & Wilson, 1992). The instrument was designed to assess an individual’s satisfaction with the constructs assessed in the scales that comprise the Circumplex Model. Thus, this measure provides a specific assessment of boundary satisfaction as well as a more general assessment of family satisfaction. Very high scores suggest that respondents “feel positive and happy most of the time. Life is enjoyable, interesting and free of tension...the future looks promising.” On the other hand, very low scores suggest that respondents “feel unhappy about life and often experience pressures and problems.”

The business satisfaction measure was adapted from Olson & Wilson’s (1992) family satisfaction scale for the purpose of this study. Each statement was reworded to reflect satisfaction in the business context. The response options for the original instrument range from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied.” In the version adapted for this study, the response “does not apply” was added to the range of potential answers because pilot testing of the instrument suggested that these items might not apply to all family business owners. Responses indicating that the item “does not apply” were not included in the calculation of the scale score for this measure.

Family functioning was assessed using the family strengths scale from the Family Assessment Package (Olson et al., 1996). This scale was developed in an effort to operationalize healthy family functioning. The family strengths scale used in the current study consisted of 12 items where answer options range from “does not describe our family at all” to “describes our family very well.” Scale scores were calculated by summing participant respondents on each of the 12 items. Higher scores indicated better perceived functioning of the family.

Two indicators of business functioning were used. The first was the business strengths scale, which was an adaptation of the Olson et al. (1996) family strengths scale. This item was designed to tap subjective and intangible business strengths. Each of the 12 items from the original scale was reworded to reflect strengths within the business, with answer options ranging from “does not describe our business at all” to “describes our business very well.” High scores indicated better reported functioning.

The second indicator of business functioning was a single item created by the research team. The item was designed to assess perceptions of the problems associated with business finances by asking respondents to indicate the frequency with which there were cash flow problems in the business during the preceding year. Answer options ranged from “every week” to “never.”

Examination of the distributions of scale scores revealed unacceptably high levels of skewness for all variables except work-to-home negative spillover and the satisfaction variables. The affected scale scores were transformed to bring skewness to acceptable levels. A square root transformation was used for business enmeshment and cash flow problems, a log transform was used for all other variables.

Participants

For the purposes of this study, a family business was defined as a business in which at least one member of the family worked as his or her primary source of livelihood and in which at least one other family member was actively involved, whether paid or unpaid. To qualify for participation, each respondent had to be an active owner of the business. This definition is clearly more restrictive than others (e.g. Winter, Fitzgerald, Heck, Haynes, & Danes, 1998) in that it requires the active involvement of at least one other family member.

Compiling a sampling frame of family businesses is always challenging, and especially so when the goal is to locate businesses involving multiple family members. One common strategy is to ask randomly-dialed householders if they are involved in a family business, but this strategy yields a plethora of home-based one-person businesses which were not the focus of this study. As a result, we compiled our own list of approximately 1000 businesses in our state. Telephone directories, magazines, newspapers, and personal networks were used to compile a list of 985 businesses in all regions of a mid-western state that were thought or known to be family-owned, based on their advertising or personal referrals.

Data were gathered via a survey administered in three parts between June and November 1999. The survey was sent to each of these businesses. In the first wave, 187 (19%) businesses responded. In Wave 2, 139 (74% of Wave 1) responded, and in Wave 3, 104 (75% of Wave 2) responded. This rate of response compares favorably to previous family business studies (i.e. the response rates in the most recent Mass Mutual studies were 3 and 10.3% in 2002 and 1997, respectively) (Mass Mutual Financial Group, 1997, 2003).

To assess representativeness, we compared the sample in the present study to that of a national random sample of family businesses (Winter et al., 1998). The national study used a more inclusive definition of family businesses than the present study, specifically because it included one-person businesses. As a result, we expected that the businesses in the present study would be older and larger, and this turned out to be true, 89% of the businesses in the present study were founded at least 10 years ago compared to 53% in the national sample and 58% of the businesses in the present study employed more than 10 people compared to 14% in the national sample. The respondents themselves, however—the business owners/managers—were quite similar: in both samples, over 70% were male and over 70% had completed education beyond high school.

Of the 187 respondents to phase one, 147 (78.6%) were male and 40 (21.4%) were female. The average age was 52.40 (SD=11.33). A majority of the respondents were married (n=165, 88.2%). One respondent (0.5%) did not finish high school, 41 (21.9%) obtained a high school diploma, 43 (23.0%) completed some college work, 58 (31.0%) completed college, 16 (8.6%) completed some graduate work, and 28 (15.0%) obtained a graduate degree. Respondents who had been in business longer were significantly more likely to complete the three phases of the present study, this was the only difference from those who dropped out.

Most of the respondents (n=107, 57.2%) were first generation owners, 53 (28.3%) were second generation, 20 (10.7%) were third generation, and 7 (3.7%) were fourth generation or more. The mean proportion of the family business that was owned by the respondent was 75% (SD=30). The average participant was 27.17 years of age when s/he started working in the business (ME=25.00, SD=11.81).

Of the 187 respondents, 176 (94.1%) considered their business to be a family venture. This question was asked to obtain the respondent’s subjective opinion about the family nature of his or her business. The oldest business was begun in 1837 and one was started during 1999, the year data were collected. The mean year in which business began was 1962.

The average number of employees in the business was 56.75 (SD=211.37), although there was a great deal of variability in terms of the total number of employees working in the business (the median was only 12). A few very large firms participated in the study while a majority of the businesses were relatively small. Similar differences were also observed when the number of employees was assessed in terms of full- and part-time status.

Analyses and Results

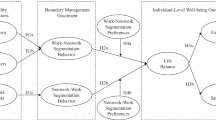

Data analyses consisted of a series of regressions designed to test for the presence of direct relationships between boundaries and functioning, as well as indirect relationships mediated by satisfaction. In order to test the mediation hypothesis, Baron and Kenny (1986) suggest that a series of standard regression models be estimated. First, the mediator should be regressed on the predictor variables. A condition for mediation is that the relationship between the predictor and the mediator is statistically significant in this equation. Next, the outcome variable should be regressed on the predictor variables. As in the prior equation, the relationship between the predictor and the outcome should be significant. Finally, the outcome variable should be regressed on both the predictors and the mediator. In this equation, the relationship between the predictor and the outcome should be weaker than in the first equation. If the relationship between the predictor and the criterion is no longer significant, perfect (as opposed to partial) mediation is said to exist (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

Model 1: Family Strengths

To test this model, family satisfaction (the hypothesized mediator) was regressed on the four predictor variables, two indicators of individual boundaries and two indicators of family boundaries. These results are shown in Table 3. The boundary variables accounted for a statistically significant 37.4% of the variation in family satisfaction. Standardized regression coefficients were negative and statistically significant for one indicator of family boundaries (disengagement) and one indicator of individual boundaries (home-to-work negative spillover). Based on non-significant regression coefficients in this analysis, it would not be possible for family satisfaction to mediate the relationship between the outcome variable of family strengths and the predictor variables of family enmeshment or individual work-to-home negative spillover.

Next, the measure of family strengths (the outcome variable) was regressed on the predictor variables with and without family satisfaction, these results are shown in Table 4. Both analyses accounted for significant proportions of the variation in family strengths, although including the mediator almost doubled the percent of explained variation. The regression coefficient for family disengagement was negative and statistically significant in both models, although weaker by more than half when the mediator of family satisfaction was included—this result indicates partial mediation. The negative coefficient for home-to-work negative spillover was also reduced by more than half when the mediator was included, and fell below statistical significance. This result indicates perfect or full mediation by family satisfaction of the relationship between the individual boundary indicator of home-to-work negative spillover and the outcome of family strengths. As before, the coefficients for enmeshment and Work-to-home negative spillover were not significant, indicating that these variables were not related to business strengths in either a direct or a mediated fashion. Thus, perceived family strengths were greater when satisfaction was higher, when disengagement was lower (a relationship both direct and mediated through satisfaction), and when negative spillover from home to job was lower (a relationship fully mediated through satisfaction).

Despite the high proportion of explained variance, conclusions about mediation must be drawn cautiously. Disengagement (one of the predictor variables) and family satisfaction (the mediator) were quite strongly related to one another, as the standardized regression coefficient of −.**607 in Table 3 reveals. Given their shared variance, it is not surprising that including family satisfaction in the models shown in Table 4 would reduce the strength of the relationship between disengagement and the outcome of family strengths.

Model 2: Business Strengths

The mediation hypothesis was then tested for business functioning. Two outcomes were tested, business strengths and cash flow problems. Following the same analytic sequence, we first regressed business satisfaction on the two indicators of individual boundaries (home-to-work and work-to-home negative spillover) and the two indicators of business boundaries (disengagement and engagement). This model accounted for a statistically significant 27.2% of the variation in business strengths. As with the test of family satisfaction, the coefficients were negative and significant only for disengagement and for home-to-work negative spillover (see Table 3). The non-significant coefficients indicate that the relationships between business strengths and enmeshment or Work-to-home negative spillover were not mediated by business satisfaction. As before, we then regressed business strengths on the four boundary indicators, with and without the mediating variable of business satisfaction. The adjusted R 2 was .188 when the mediator was excluded and .279 when the mediator was included. The regression coefficient for disengagement was smaller and significant only at the level of a trend, indicating partial mediation, and the coefficient for home-to-work negative spillover fell from significance, indicating perfect mediation, when the mediator was included in the regression equation. Coefficients for enmeshment and work-to-home negative spillover were not significant in either model, indicating no direct or mediated relationships with business strengths. Thus, perceived business strengths were greater when satisfaction was higher, disengagement was lower (a relationship both direct and mediated through satisfaction), and when negative spillover from home to job was lower (a relationship fully mediated through satisfaction).

Model 3: Business Performance

The same analytic sequence used above was replicated using cash flow problems as the outcome indicator of business performance. The test of the relationship between business satisfaction and the predictor variables is the same as reported above for model 2. The results of the regressions with and without the mediator are shown in Table 4. Statistically significant variation in business performance was accounted for by model 3. Unique to this model was a non-significant regression coefficient for the hypothesized mediator of business satisfaction, indicating that none of the relationships between the predictors and the outcome were mediated, and that satisfaction with the business was not related to the frequency of cash flow problems. The only significant regression coefficient, with or without the satisfaction mediator, was for home-to-work negative spillover, indicating a direct and positive relationship between negative spillover and the frequency of cash flow problems. Enmeshment was also significant, but only with the satisfaction mediator.

Finally, all of the analyses just described were re-run to determine whether the inclusion of demographic control variables would alter the findings. Three additional variables were included in each regression equation, entered in a block before all other variables, education, age, and marital status. All findings were robust to these controls.

Discussion

This study examined the relationships between several measures of boundaries and family and business functioning. It also considered the extent to which satisfaction mediated these relationships.

In the family system, satisfaction mediated the negative relationships between home-to-work spillover and family functioning (indicated by family strengths), and disengagement and family strengths. Family satisfaction fully mediated the contribution of home-to-work spillover, indicating that satisfaction was more important than spillover for family strengths. In contrast, satisfaction only partially mediated the relationship between disengagement and family functioning. The two other boundary measures, work-to-home negative spillover and permeable family boundaries (enmeshment), were not related to family strengths either when mediated through family satisfaction or when considered alone.

Model 2 presented some interesting parallels and discrepancies. This model tested the relationships between business boundaries, business satisfaction and business strengths. Two of the four boundary measures—home-to-work negative spillover and disengagement—were negatively and significantly related to business strengths. When the mediator was entered into the multivariate equation, it fully accounted for the prior relationship between spillover and strengths, and accounted for all but a trend-level relationship between disengagement and strengths. Once again, work-to-home negative spillover and enmeshment were not related to either satisfaction or to strengths.

In both models 1 and 2, disengagement was related to family functioning beyond the contribution of satisfaction, and the coefficients for enmeshment were not significant. These results suggest that disengagement was more important than enmeshment, in a negative way, for system functioning. This finding is surprising given the conventional wisdom that family business members should strengthen the boundaries distinguishing the systems (e.g. Marshack, 1998; Rosenblatt et al., 1985). It may be that helping families delineate boundaries that are less rigid and more fluid may have a more discernable impact on systemic functioning—at least from a subjective perspective—than strengthening those boundaries as commonly suggested.

In model 3, financial performance served as the criterion variable. Here, enmeshment and home-to-work negative spillover were directly related to business performance, not mediated through satisfaction. These findings suggest that satisfaction may not be an important component of systemic functioning when the functioning is defined using a more tangible criterion such as cash flow. It is also interesting that when financial performance was the criterion, then the more traditional family business consulting wisdom about keeping family boundaries distinct seemed to be more reasonable advice, given the positive relationship between home-to-work negative spillover and financial performance. Evidently, the rule may still apply when concerns are related to the financial performance of the business.

The relationship between specific boundary subscales and systemic outcomes warrants additional discussion. First, the home-to-work negative spillover scale emerged as a significant predictor of systemic outcomes in all three models—negative for strengths and positive for financial performance. However, in the models using strengths as the outcome variable, the relationship between spillover and strengths became insignificant when the mediator was added to the equation. These findings suggest that negative spillover from the home to a family business is not negative for the functioning of either the family or the business unless the respondent is dissatisfied. This was the relationship that was hypothesized in the present study.

Rather than being mediated through satisfaction, the relationship between home-to-work negative spillover and the financial performance of the business was direct. Thus, independent of level of satisfaction, when an individual’s family or personal life is perceived as interfering with the business, the financial performance of the business may be affected. Although we did anticipate it, this finding makes intuitive sense. Practical limitations may impose a constraint on the financial performance of the business. Satisfaction may not be very important if the respondent simply has fewer resources to devote to the business because of personal or family constraints, constraints that may impede the financial performance of the business.

Contrary to our hypotheses, work-to-home negative spillover was never related to system outcomes. At least for the current sample, when individuals perceived that their business prevented them from performing important personal and family responsibilities, neither the functioning of the family nor the financial performance of the business were significantly impeded. This finding was not only unexpected but is inconsistent with the results of many studies of work-family relationships among employees, where negative spillover from work to home more frequently emerges as significant. Our results generally correspond to those of Hundley (2001), however, who found no significant relationship between self-employment and work-to-home spillover, except among fathers of pre-school children.

A potential explanation is that families may have more choices than firms do in the way they adapt and adjust. Since firms generally function in relatively orderly fashion following similar conventions (e.g. accounting practices, government regulation, “generally accepted business practice”), families may have greater flexibility and adaptability to manage negative spillover, thus reducing the impact of negative spillover from work. It may also be that the work-to-home negative spillover items did not adequately capture the experiences of family business owners, given their ownership stake in the business. Perhaps effects of work-to-home negative spillover would be more evident if family functioning were measured in terms of the quality and quantity of time that family members have to spend with one another.

Conclusions

Three regression models were hypothesized in this study and each was significant. In the first, scores on the five subscales predicted 59.8% of the variability in family strengths. In the second, 27.9% of the variability in business strengths was predicted and in the third, 17.5% of the variability in financial performance was predicted. The models showed that boundaries are related to functioning in both the business and the family system. Although the predicted variability in all three models was significant, the predictive power of boundaries in the family strengths model was particularly strong. This may be because most of the scales were specifically designed to measure the constructs of boundaries, satisfaction, and functioning in the family system.

This study was designed to address a gap in the family business literature. Much of this literature has suggested that many of the problems facing family owned firms are related to the overlap between the family and the business and that boundaries function to regulate that overlap. Several regression models were proposed to investigate the relationships between boundaries and system performance. Satisfaction served as a mediating variable.

Results of the study offered partial confirmation for the boundary hypothesis. In particular, it appears that satisfaction mediates the relationship between boundaries and performance when performance was defined in subjective ways but not when it was defined in terms of the objective cash flow measure. In addition, rigid boundaries (disengagement) seemed more important to the prediction of subjective performance while permeable boundaries (enmeshment) seemed more predictive of objective performance. Taken together, these results suggest that boundaries are dynamic and complex constructs and that the impact of boundaries issues depends, at least in part, on how success is defined.

References

Aldrich H. E., Cliff J. E., (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective Journal of Business Venturing 18:573–596

Baron R. M., Kenny D. A., (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51:1173–1182

Bond J. T., Galinsky E., Swanberg J. E., (1998). The 1997 national study of the changing workforce. Families & Work Institute, New York

Bork D., Jaffe D. T., Lane S. H., Dashew L., Heisler Q. G., (1996). Working with family businesses. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Bowen M., (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aronson, New York

Colapinto J., (1991). Structural family therapy. In: Gurman A. S., Knoskern D. P., (Eds.) Handbook of family therapy. Bruner/Mazel Publishers, New York, 417–443

Davis P., Stern D., (1996). Adaptation, survival, and growth of the family business: An integrated systems perspective. In: Aronoff C. E., Astrachan J. H., Ward J. L., (Eds.) Family business sourcebook II. Business Owner Resources, Marietta, Georgia, 278–309

Fischer J., Corcoran K., (1994). Measures for clinical practice: A sourcebook. Volume 1: Couples, families and children (2nd ed.). The Free Press, New York

Fisher L., (1982). Transactional theories but individual assessment: A frequent discrepancy in family research Family Process 21:313–320

Haynes G., Walker R., Rowe B., Hong G., (1999). The intermingling of business and family finances in family-owned businesses Family Business Review IXX:225–239

Huang Y., Hammer L., Neal M., Perrin N., (2004). The relationship between work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict: A longitudinal study Journal of Family and Economic Issues 25:79–100

Hundley G., (2001). Domestic division of labor and self/organizationally employed differences in job attitudes and earning Journal of Family and Economic Issues 22:121–139

Kahn R., Wolfe D., Quinn R., Snoek J., Rosenthal R., (1964). Organizational stress: studies in role conflict and ambiguity. John Wiley, New York

Kaslow F. W., Kaslow S., (1992). The family that works together: Special problems of family businesses. In: Zedeck S., (Eds.) Work, families, and organizations. Josey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, 312–361

Kepner E. (1983). The family and the firm: A coevolutionary perspective. Organizational Dynamics Summer 57–70

Kerr M. E., Bowen M., (1988). Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. W.W. Norton & Company, New York

Marshack K., (1998). Entrepreneurial couples: Making it work at work and at home. Davies-Black Publishing, Palo Alto, CA

Mass Mutual Financial Group. (1997). American family business survey, 1997. Author, Springfield, MA

Mass Mutual Financial Group. (2003). American family business survey [Online]. Available: http://www.ffi.org/massmutual_survey.pdf, and summarized at http://www.niagara.edu/ciaer/2003/2

Masuo D., Fong G., Yanagida J., Cabal C., (2001). Factors associated with business and family success: A comparison of single manager and dual manager family business households Journal of Family and Economic Issues 22:55–73

Minuchin S., (1974). Families and family therapy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Olson D. H., (1999). Circumplex model of marital and family systems Journal of Family Therapy 22:144–167

Olson D. H., McCubbin H. I., Barnes H., Larsen A., Muxsen M., Wilson M., (1989). Families: What makes them work (2nd ed.), Sage Publishing, Los Angeles

Olson D. H., Tiesel J. W., Gorall D. M., Fitterer C., (1996). Family assessment package. University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN

Olson D. H., Wilson M., (1992). Family satisfaction. In: Olson D. H., McCubbin H. I., Barnes H., Larsen A., Muxen M., Wilson M., (Eds.) Family inventories. Life Innovations, St. Paul, MN, 43–50

Roehling P., Roehling M., Moen P., (2001). The relationship between work-life policies and practices and employee loyalty: A life course perspective Journal of Family and Economic Issues 22:141–170

Rosenblatt P. C., de Mik L., Anderson R. M., Johnson P. A., (1985). The family in business. Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers, CA

Swogger G., Johnson E., Post J. M., (1988). Issues of retirement from leadership in a family business Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 52:150–157

Vinton K. L., (1998). Nepotism: An interdisciplinary model Family Business Review XI:297–303

Weigel D. J., Ballard-Reisch D. S., (1997). Merging family and firm: An integrated systems approach to process and change Journal of Family and Economic Issues 18:7–31. (Please double check p. 5)

Winter M., Fitzgerald M. A., Heck R. K. Z., Haynes G. W., Danes S. M., (1998). Revisiting the study of family business: Methodological challenges, dilemmas, and alternative approaches Family Business Review XI:239–252

Wiseman K. K., (1996). Life at work: The view from the bleachers. In: Comella P. A., Bader J., Ball J. S., Wiseman K. K., Sagar R. R., (Eds.) The emotional side of organizations: Applications of Bowen theory. Georgetown Family Center, Washington, DC, 29–38

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zody, Z., Sprenkle, D., MacDermid, S. et al. Boundaries and the Functioning of Family and Business Systems. J Fam Econ Iss 27, 185–206 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-006-9017-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-006-9017-8