ABSTRACT

This study of 76 married or cohabiting two-earner families examined the influence of spouse/partner involvement in childcare and other demand and resource variables on mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work. Gender had a significant influence on the relationship between spouse/partner involvement in childcare and support for paid work. Mothers were more likely to report support for paid work when their spouse/partner shared more of the responsibilities associated with childcare. Fathers were more likely to report support for work when their spouse/partner shared fewer of the responsibilities associated with childcare. The findings also suggest that fathers’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for work are more sensitive to ecological factors than are mothers’ perceptions of support for work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A considerable body of research has focused on family–work conflict (Perry-Jenkins, Repetti, & Crouter, 2000). However, surprisingly few studies have examined the influence of childcare on this area of parents’ wellbeing. Childcare is so central to working parents’ lives that even when other aspects of the parent’s family life or employment are going smoothly, having childcare problems is a significant source of emotional distress for working parents (Press, Fagan, & Bernd, 2006).

In the present study, we examine the degree to which spouse/partner involvement in childcare responsibilities influences parents’ family-to-work conflict, which, for the purpose of this study, is defined as mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions that their spouse/partner supports their paid work. Mothers historically have assumed the major share of responsibility for childcare, even when women work full-time (Hochschild & Machung, 1989). However, fathers have also taken on significant responsibility for childcare support. Recent studies reveal that 17% of fathers are primary childcare providers to their children (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002). Several small-scale studies also reveal that fathers are involved in various aspects of their young child’s daycare program, including dropping off, picking up, communicating with staff, and fulfilling a variety of other responsibilities for children (Fagan, 1997).

A second objective of this study is to examine the role that gender plays in relation to parents’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work. We are particularly interested in the role that gender plays in the association between spouse/partner participation in childcare and parent perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work.

Theoretical Approach

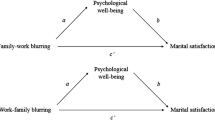

Ecological systems theory is the theoretical foundation of this study. However, we also suggest that gender relations in the family and in society play an important role in the manner in which ecological factors influence individuals. According to ecological systems theory, work and family are social microsystems that involve the individual in patterned behaviors, social relationships, roles, and commitments. These socially embedded relationships involve both work and family demands and resources that have the potential to offset the deleterious affects of systems that at times exceed the limits of one’s energy and time (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Voydanoff, 2004a). An ecological approach suggests that no one aspect of one’s family or work situation accounts for work–family conflict. Instead, a multidimensional approach is necessary. We use the model of work and family demands and resources to test the effect of spouse/partner involvement in childcare on family–work conflict (i.e., Westman & Etzion, 1995). Voydanoff (2004a) defines resources as, “structural or psychological assets that may be used to facilitate performance, reduce demands, or generate additional resources” (p. 398). For the purpose of this study, we examine one work resource—mothers’ and fathers’ job flexibility. The family resource included in this study is spouse/partner involvement in childcare. Accordingly, father involvement in childcare would be considered a resource to mothers, and mother involvement in childcare would be considered a resource to fathers. Voydanoff (2004a) defines demands as, “structural or psychological claims associated with role requirements, expectations, and norms to which individuals must respond or adapt by exerting physical or mental effort” (p. 398). Work-related demands include working long hours. Family-related demands include number of preschool children and housework responsibilities. Voydanoff (2004a) also suggests an additional resource—boundary-spanning resources. These resources are defined as “aspects of work and family roles that directly address how work and family connect with each other” (p. 401). Boundary-spanning resources are not included in our analysis.

It is well known that gender plays an important role in understanding spousal/partner strategies for fulfilling work and household responsibilities (Ferree, 1991; Voydanoff, 2004b). Rutter and Schwartz (2000) state, “Social norms for gender differences in marriage have nearly irresistible power” (p. 64). Even when husbands and wives attempt to share breadwinning and family roles, marriage and having children set in motion a wife’s duties to household and childcare tasks and a husband’s duties to earn money for the family (Fox & Murry, 2000; Hochschild & Machung, 1989).

The tendency for wives employed in the labor force to do most of the housework and childcare and for husbands to do fewer of these tasks has been explained by the doing-gender approach. In essence this approach suggests that doing, or not doing, housework and childcare is a symbolic enactment of gender relations between husbands and wives (West & Zimmerman, 1998). Wives fall into a pattern of doing family-related tasks, and husbands fall into a pattern of doing breadwinning tasks, as a means of enacting their gender roles. Social structure is also part of the construction of gender relations in the family and workplace (Risman, 1989). According to this perspective, institutional structures in society reproduce traditional gender relationships in the family and workplace. For example, employers are often reluctant to allow male workers to take advantage of family-supportive policies such as paternity leave and flextime (Pleck, 1993). As a consequence, mothers frequently must assume responsibility for childcare, with fathers assisting in these responsibilities when they have extra time or when mothers pressure them to help (Fagan & Palm, 2004).

Although employed wives and husbands may fall into such gendered relationship patterns, they may not necessarily be satisfied with those relationship patterns. In the present study, we suggest that these relationship patterns are manifested in parents’ family–work conflict (perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work). For example, wives may perform most of the childcare responsibilities, but they may also perceive less spouse/partner support for paid work as a result of doing most of these tasks. Hochschild and Machung (1989) have suggested that wives and husbands provide each other with different types of supports (see also Barnett, 2005). What makes a wife feel supported in her paid work role is her husband’s sharing of housework and childcare. What makes a husband feel supported in his paid work role is his wife’s appreciation of his breadwinning. Based on Hochschild and Machung’s (1989) hypothesis, we expect to find a positive relationship between wives’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work and husbands’ childcare involvement. However, the gendered perspective also suggests that in respect to childcare involvement, wives may not be viewed as a resource to husbands. That is, we do not expect to find a significant relationship between husbands’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work and wives’ levels of childcare involvement. In essence, we are saying that the relationship between ecological factors and family–work conflict is influenced by gender relationships (see also Voydanoff, 2004b). Father involvement in childcare will be viewed as a resource to mothers, but mother involvement in childcare will not be viewed as a resource to fathers.

Literature Review

Spouse/partner involvement in childcare arrangements (e.g., daycare centers) may be an especially important ecological factor in relation to spouse/partner perceptions of support for paid work. Parents may experience considerable family–work conflict when their employer asks them to work overtime, whereas their childcare provider expects prompt pick-up before closing time. Similarly, many care settings are usually not available if parents must attend an early work meeting. If an employee or employer tries to change the shift away from day time hours, most formal care arrangements will not adapt to the change, even temporarily. The potential for conflict between work and family demands may be partially mitigated if the other parent shares equally in the responsibilities of childcare. For example, on days when parents must work extra hours, the other parent’s availability to pick-up from daycare may greatly enhance one’s perception that the spouse/partner supports involvement in paid work. In the present study, we hypothesize a positive relationship between perceived support for paid work and the other parent’s childcare involvement among mothers but not among fathers.

We limit our sample to families with young children in daycare centers in this study. For many parents, center care may be the desired choice because they assume the quality is better (Adams & Rohacek, 2002; Wolfe & Scrivner, 2004). However, daycare centers may be less supportive of parents’ work hours than other more flexible forms of childcare (Henly & Lyons, 2000). Most centers have strict policies regarding drop-off and pick-up times and often charge high fees for being late.

The paucity of research on parental childcare responsibility makes it difficult to know which aspects of involvement may influence mothers’ and fathers’ perception of spouse/partner support for paid work. Consequently, we examine several aspects of responsibility that affect parents on a regular basis—transporting children to and from childcare, communicating with staff, paying bills, making sure that children’s material needs are met while in childcare, and keeping in touch with the childcare center when the child is sick. We focus specifically on aspects of involvement that are required of parents when having a child in daycare rather than on aspects of involvement that are voluntary, such as fundraising or accompanying children on trips.

As noted earlier, the ecological/systems approach used in this study necessitates a multidimensional approach to examining family–work conflict. We therefore include in our analysis several work and family demands and resources. We expect in general that demand variables will be associated with increased family–work conflict (lower levels of perceived spouse/partner support for paid work), and resource variables will be associated with decreased conflict (higher levels of perceived spouse/partner support for paid work). We recognize that gender may influence the pattern of relationships between perceived support for paid work and the demand or resource variables. However, with the exception of spouse/partner involvement in childcare and participation in household tasks, we are not aware of research studies that could be used to suggest how gender influences the relationship between other demand or resource variables and the dependent variable. As a result, we formulate hypotheses that are consistent with the ecological perspective—demand variables are associated with increased family–work conflict and resource variables are associated with decreased family–work conflict.

The demand variables considered in this study include long work hours, housework responsibilities, and number of preschool-age children in the household. Long work hours have been consistently associated with work–family conflict (Clark, 2001; Dilworth, 2004; Hill, Hawkins, Ferris, & Weitzman, 2001; Voydanoff, 2004a). Studies have found that women’s paid work hours account for as much as 19% of the variance in work–family balance (Dilworth, 2004; Hill et al., 2001). Working long hours has been found to limit the amount of time individuals have to participate in family activities/family work (Almeida, Maggs, & Galambos, 1993), often resulting in a sense of imbalance between the work and the family domains. We hypothesize that both mothers’ and fathers’ long work hours will be associated with lower levels of mothers’ and fathers’ reports of spouse/partner support for paid work.

Parents’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work are also likely to be affected by the demands associated with housework. Although women have cut their hours spent on housework in the last few decades (Bianchi, Milkie, Sayer, & Robinson, 2000; Coverman & Sheley, 1986; Shelton, 1992) and more men seem to be getting involved in housework (Bianchi et al., 2000), women still perform most of it (Gershuny & Robinson, 1988; Milkie & Peltola, 1999; Shelton, 1992), regardless of the number of paid work hours (Dilworth, 2004) and regardless of marital status (South & Spitze, 1994). Women in dual-earner couples who perform most of the housework report a greater degree of work–family imbalance (Milkie & Peltola, 1999; Wiersma & van den Berg, 1991). In the present study, we examine the influence of parents’ proportional contribution to housework on perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work. Consistent with the gender perspective of this study, we expect to find that mothers who perform proportionally more housework will report lower levels of spouse/partner support for paid work. We do not expect to find a significant relationship between fathers’ proportion of housework and their perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work.

Time spent on housework activities is also evidently affected by the number of preschool-age children present in the household (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000; South & Spitze, 1994). Results vary in regard to how the presence of children in the household and their ages affect women’s work–family balance. For instance, Grzywacz and Marks (2000) found that having children of any age predicted greater work–family conflict. In a later study, Grzywacz, Almeida, and McDonald (2002) report that those with a child under the age of six had a higher level of negative spillover from family to work than respondents without children. On the other hand, Milkie and Peltola (1999) revealed that for all working married women in their sample, the number of children and their ages were not significant predictors of women’s sense of successful work–family balance. However, the authors found that for full-time working mothers, the presence of children under 6 years of age in the household had a negative impact on mothers’ sense of work–family balance. Although the impact of having young children at home on mothers’ work–family balance is not consistent across studies, we do believe that having young children, especially under the age of six, creates a great deal of family demands on the parents, which justifies its inclusion in our analysis. Consistent with the ecological theory, we expect to find that number of preschool-age children will be associated with perceptions of reduced spouse/partner support for paid work among mothers and fathers.

We examine two work resource variables in this study—mothers’ and fathers’ job flexibility. Researchers have found perceived job flexibility to be related to one’s lower levels of work–family conflict (Hammer, Allen, & Grigsby, 1997; Voydanoff, 2004a), as well as to one’s higher levels of work–family balance after controlling for paid work hours, housework hours, and gender (Hill et al., 2001). Similarly, Madsen (2003) found that individuals who had the flexibility to work from home at least twice a week had lower levels of work–family conflict compared to employees who worked on-site only. We hypothesize that mothers will report greater support for paid work from their spouse/partner when both they and their spouse/partner have flexible job arrangements. Further, we hypothesize fathers will report greater support for paid work from their spouse/partner when both they and their spouse/partner have flexible jobs.

To summarize, the present study examines the following hypotheses:

-

1.

Mothers will report higher levels of spouse/partner support for paid work when the father shares more responsibility for childcare. There will be no significant relationship between fathers’ reports of levels of spouse/partner support for paid work and mothers’ childcare involvement.

-

2.

Mothers and fathers will report less spouse/partner support for paid work when they and their spouses/partners work long hours.

-

3.

Mothers will report greater spouse/partner support for paid work when they perform proportionally less housework. Fathers’ reports of spouse/partner support for paid work will not be related to their involvement in housework.

-

4.

Mothers and fathers will report less spouse/partner support for paid work when they have a greater number of preschool-age children in the household.

-

5.

Mothers and fathers will report greater spouse/partner support for work when they and their spouses/partners have higher levels of job flexibility.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Our analyses are based on data from structured, self-administered surveys with 76 families recruited at daycare centers throughout the Philadelphia region. The data were collected between June and November 2000. To participate in the study, families had to meet the following criteria: (1) the child lives in the same household with his/her biological mother and biological father, and (2) both parents work more than 20 hours per week.

Families were asked to fill out three structured surveys. One was to be completed together by the mother and father, one by the mother only, and one by the father only. Parents were asked questions about household composition, employment, household responsibilities, childcare involvement, and spouse/partner support for paid work.

The participants in the study are predominantly white and highly educated. Many mothers in the study were college graduates (31%) or had completed a graduate degree (49%). Similarly, many fathers were college graduates (35%) or had completed a graduate degree (35%). Close to 75% of the families had an annual income of $60,000 or more. The majority of couples in the sample were married (88%); a smaller percentage of couples were not married but cohabiting (12%). Most of the respondents were white (81%), and a smaller percentage were African-American (11%), Latino (4%), Asian (1%), or unidentified (3%).

The mean age of mothers in the study was 35.3 years (SD=5.6), and the average age of fathers was 37.3 years (SD=6.4). All families had at least one preschool-age child. The median number of preschool-age children in the household was one (SD=.66). Approximately 34% of the families had two preschool-age children, 5% had three preschool-age children, and 1% had four preschool-age children. Approximately one-half of the youngest children in the families were males (48%) and about one-half were females (52%).

Instruments

Spousal Support for Work and Parenting (Greenberger, Goldberg, & Hamill, 1989) is used to measure fathers’ and mothers’ perceptions of their spouse/partner’s support for their paid work. This instrument contains two subscales, one concerning support for work and one concerning support for parenting. Only the 15-item subscale concerning emotional and instrumental support for work is used in this study. A four-point Likert-type response format is used with responses ranging from 1=definitely not true to 4=very true. A high score on the subscale indicates greater spouse/partner support for one’s paid work. Sample items include: “My spouse/partner listens to me intently about work problems,” “My spouse/partner is understanding when I have to work overtime,” and “My spouse/partner does not complain about the amount of time I spend working.” The sample reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s α) for this subscale are .83 for mothers and .86 for fathers.

Based on McBride and Rane’s (1997) method for measuring parental involvement, an instrument was developed to measure the degree to which mothers and fathers share or do not share family and household tasks. Mothers and fathers were asked to jointly indicate who assumes responsibility for various tasks at home. The items included preparing meals, dressing children in the morning, getting children ready for bed, buying clothing, taking children to the doctor, cleaning and straightening the house, and grocery shopping. A five-point Likert-type response format is used ranging from 1=always wife to 5=always husband. The midpoint of the scale (3) suggests that wives and husbands share tasks equally. Because a high score on this scale denotes greater participation of fathers, the items were reverse coded when testing the association between mothers’ household tasks and mothers’ reports of spouse–partner support for paid work. The reliability coefficient for the scale (Cronbach’s α) was .66.

Job flexibility is measured using the scale, Supervisor Flexibility (Greenberger et al., 1989). This nine-item scale measures the degree of flexibility or responsiveness regarding a respondent’s family needs. Items are measured on a three-point scale, ranging from 1=seldom or never to 3=usually or always. Sample items included, “If I receive phone calls from home (at work) my supervisor is understanding” and “My supervisor lets me work from home if I can’t come in on a given day because of family matters.” The reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s α) for this scale were .87 for mothers and .89 for fathers.

Mothers and fathers were also asked to indicate the highest level of education completed, racial/ethnic background, number of hours worked in a week, and number and ages of children in the household. They were also asked to calculate their total family income from all sources for the past year ending December 31. Number of work hours was recoded into a variable called long work hours. Mothers and fathers who worked 50 or more hours per week were coded as 1, and mothers and fathers who worked fewer than 50 hours per week were coded as 0.

Two instruments were used to measure childcare involvement. Both parents jointly completed a form indicating who dropped off and picked up from childcare each day during the past five workdays. Data from this form were used to determine which mothers and fathers transported their children to or from daycare 50% or more of the time. The second instrument (Childcare Responsibility) consisted of four items. Mothers and fathers were asked to jointly indicate who assumes responsibility for various childcare tasks. The items included paying daycare bills, communicating with staff, keeping in touch with the daycare center when the child is sick, and making sure the child has a change of clothing at daycare. A five-point Likert-type response format is used ranging from 1=always wife to 5=always husband. The mid-point of the scale (3) suggests that wives and husbands share tasks equally. The reliability coefficient for the scale (Cronbach’s α) was .74.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the major study variables. Fathers worked an average of 45.6 hours per week, approximately 9 hours more than mothers, who worked an average of 36.4 hours per week. Ten out of 76 mothers (13%) worked at least 50 hours per week. Twenty-nine out of 76 fathers (38%) worked at least 50 hours per week. Mothers and fathers reported having very similar levels of job flexibility. The average item score for mothers’ job flexibility was 2.6 (response format goes from 1 to 3) and for fathers it was 2.5. These results suggest the participants of this study had flexible jobs, possibly due to the large number of professionals in the study.

Descriptive statistics regarding household and family tasks revealed that mothers and fathers on average shared such tasks (M=3.0, SD=.9; response format goes from 1 to 5). With respect to childcare drop-offs and pick-ups, in 57 out of 76 families the mother transports 50% of the time or more. In 26 out of 76 families, the father transports 50% of the time or more. The total number of mothers and fathers who transport 50% of the time or more is greater that 76 because some couples transport their child together to the childcare center. The average item score for the Childcare Responsibility scale (scores go from 1 to 5) was 3.87 (SD=1.13) for mothers and 2.82 (SD=1.10) for fathers. These findings suggest that mothers assumed considerably more responsibility for childcare centers than did fathers.

On the dependent variable, mothers reported slightly higher levels of spouse/partner support for paid work than fathers. The mean item score for mothers’ perceptions of spouse/partner support was 3.19 (response format goes from 1 to 4) and for fathers’ perceptions of support was 3.05. These findings suggest that on the average both mothers and fathers feel that it is mostly true that their spouse/partner supports their paid work.

Preliminary Analyses

Factor analyses were conducted on the childcare involvement variables in order to reduce the number of independent variables in the study. Two variables (spouse/partner transports the child to and from daycare 50% of the time or more and spouse/partner childcare responsibility) were subjected to this analysis, using a principal components analysis. Standardized scores for each variable were calculated before performing the analyses. The results indicated that both variables loaded on one distinct factor for the combined sample of mothers and fathers, accounting for 72% of the variance in the original variable set (eigenvalue=1.45). The variables also loaded on one distinct factor for mothers only, accounting for 66% of the variance in the original variable set (eigenvalue=1.32). Finally, the variables loaded on one factor for fathers only, accounting for 72% of the variance (eigenvalue=1.44). Based on these findings the two childcare involvement variables were combined to produce one variable, which we refer to as childcare involvement.

Bivariate Analyses

The next step in the analysis plan was to calculate Pearson Correlation Coefficients for the independent variables and spouse/partner support for paid work for all parents (mothers and fathers, see Table 1). Because we expect to find a gender effect on several relationships (e.g., other parent’s childcare involvement and support for work), we also calculate Pearson Correlation Coefficients for mothers and then for fathers. We note also that the small number of Latino and Asian parents in the sample necessitated combining several ethnicity–racial groups. Because African-American parents were the second largest ethnic/racial group in the sample, we decided to compare African-American parents with non-African-American parents. The correlations for all parents reveal a significant positive relationship between spouse/partner support for paid work and parent education, African-American parent, parent’s job flexibility, and spouse/partner’s job flexibility. Number of preschool-age children in the household is negatively related to the dependent variable for all parents.

The correlations for mothers reveal a positive relationship between the dependent variable and African-American mother and spouse/partner’s job flexibility. Whereas parent’s household tasks were not significantly related to support for paid work for all parents, parent’s household tasks were negatively related to the dependent variable for mothers. Further, whereas spouse/partner’s childcare involvement was not significantly related to support for paid work for all parents, these variables were positively related for mothers.

The correlations for fathers reveal a positive relationship between the dependent variable and father education, African-American father, and father’s job flexibility. There was a negative relationship between the dependent measure and number of preschoolers in the household. Of particular interest was the finding that there was a significant positive relationship between spouse/partner support for paid work and the father’s household tasks and a significant negative relationship between the dependent variable and spouse/partner’s childcare involvement.

The bivariate table suggests a possible gender effect for two independent variables—parent’s household tasks and spouse/partner’s childcare involvement. That is, the correlations for mothers and fathers were in opposite directions and the differences appeared to be sizeable. In order to test for the gender effect, Fisher’s r to z transformation function was calculated. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient for parent’s household tasks and spouse/partner support for paid work was significantly different for mothers and fathers (Fisher r to z transformation=3.09). Similarly, the Pearson Correlation Coefficient for spouse/partner’s childcare involvement and spouse/partner support for paid work was significantly different for mothers and fathers (Fisher r to z transformation=4.87).

Multivariate Analyses

Hierarchical regression analyses were next conducted to test for associations between spouse/partner support for paid work and spouse/partner’s childcare involvement, work and family demands, and work resources. Based on the findings of the bivariate analyses, three regression equations were calculated—one for all parents, one for mothers only, and one for fathers only. All equations included three models—the first included only controls; the second included controls plus work and family demands; and the third included controls, demands, and resources (other parent’s childcare involvement was a resource).

The first regression equation (see Table 2) included data from the entire sample of mothers and fathers (N=152). Gender of the parent was included in this analysis as well. The control variables accounted for 7% of the variance in parents’ reports of spouse/partner support for paid work. African-American parents reported significantly more support for work than did other parents. Gender of the parent was not significantly associated with the dependent variable. The demand variables increased the amount of explained variance from 7% to 10%; only the number of preschool-age children in the household approached significance in relation to spouse/partner support for paid work. The third model included the resource variables in addition to demand and control variables. The total R 2 went from 10% to 17% with the addition of the resource variables. In this model, African-American parents were still significantly more likely to report spouse/partner support for paid work. The spouse/partner’s job flexibility was positively associated with the dependent variable. There was no significant relationship between parents’ reports of spouse/partner support for paid work and the spouse/partner’s childcare involvement.

In the second regression analysis, mothers’ reports of spouse/partner support for paid work were regressed on the independent variables (see Table 3). All independent variables were the same with the exception of gender, which was not included in this analysis. As a block, the control variables were not significantly associated with the dependent variable (R 2=.06). African-American mothers were significantly more likely than their counterparts to report support for paid work. The block of demand variables also did not significantly increase the explained variance in mothers’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work, although mothers’ involvement in household tasks was negatively associated with support. Mothers who reported doing a proportionally large share of these tasks expressed receiving less support for paid work from spouses/partners. Finally, the resource variables significantly increased the variance in the dependent measure from 16% to 32%. The spouse/partner’s childcare involvement was the only variable that significantly predicted spouse/partner support after controlling for all other independent measures. That is, mothers were significantly more likely to report spouse/partner support for paid work when the other parent scored high on the childcare involvement index (i.e., transported the child to and from daycare at least 50% of the time and assumed other childcare responsibilities).

In the third regression analysis, fathers’ reports of spouse/partner support for paid work were regressed on the independent variables (see Table 4). As a block, the control variables approached significance in relation to the dependent variable (R 2=.11, p<.10). There was a trend for African-American fathers to report greater spouse/partner support for paid work. Fathers with higher levels of education also reported significantly higher levels of spouse/partner support for work. The second model, which includes the control and demand variables, also approached significance (R 2=.20, p<.10). Only one demand variable was related to spouse support for work—number of preschool-age children in the household. The third model revealed a substantial increase in explained variance (the R 2goes from .20 to .35, p<.01). Two resource variables were significantly related to father reports of spouse/partner support for paid work—the mother’s job flexibility and the spouse/partner’s childcare involvement. Fathers report lower levels of spouse/partner support for paid work when the mother assumes greater responsibility for childcare.

Discussion

The main purpose of the present study was to examine the relationship between spouse/partner involvement in childcare and mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work. A second objective was to examine the influence of gender on this relationship. We hypothesized a positive relationship between spouse/partner involvement in childcare and perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work among mothers and no relationship between these variables among fathers. The hypothesis was supported for mothers. We found a negative relationship between the variables among fathers. That is, higher levels of maternal involvement in childcare were significantly associated with lower levels of fathers’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work. Our findings are not consistent with the results of researchers such as Hochschild and Machung (1989) who found no relationship between mothers’ childcare involvement and fathers’ perceptions of support for their breadwinning role. Instead, our findings seem to suggest that mothers’ higher levels of involvement in childcare may be an obstacle to fathers’ perceived support for paid work.

According to ecological-systems theory, the resources in one’s environment have the potential to offset the deleterious affects of systems, such as work, that at times exceed the limits of one’s energy and time. Although this theoretical approach was partly supported by our findings (i.e., family demand variables such as number of preschool-age children in the household were associated with lower levels of fathers’ perceived support from spouses for paid work), this approach was not sufficient in explaining the relationship between spouse/partner’s childcare involvement and mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work. A strict interpretation of ecological theory suggests that mothers and fathers would feel greater support for work when their spouse/partner is more involved with childcare responsibilities. Although this pattern is true for mothers, it is not true for fathers. That is, mothers feel more supported when the father is more involved in childcare; fathers feel more supported when the mother is less involved in childcare. Gender clearly influences the manner in which adults define what is regarded as being a resource and what is not.

We suspect that these findings have something to do with the meanings attributed to support and work among men and women. For women, paid work means less time and less energy to devote to children and family. Since family work is central to women’s identity (i.e., doing gender approach), the impact of full-time paid work may be very different for women than it is for men. Women may deal with this dilemma by raising their expectations for spouses/partners to contribute more to meeting family needs. When this expectation is met, even if just partially met, women may feel greater ease with working. They are also likely to feel greater support for their own work from their spouse/partner.

On the other hand, family work has not been central to the male identity (Doherty, Kouneski, & Erickson, 1998). Although fathers have increased their involvement with children during the past several decades, research studies have revealed that men’s commitment to the breadwinner role has not eroded (Bernhardt & Goldscheider, 2001). We suspect that for most fathers, parenting and housework are still secondary to breadwinning. As a consequence, fathers are still viewed as a source of childcare support to mothers. In contrast, mothers are not viewed as a source of childcare support to fathers. The father’s parenting role would need to be far more central to his sense of identity before mothers would become a source of caregiving support to him.

We note a similar pattern of relationships for parental household tasks and perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work. The bivariate analyses reveal that mothers who do more of the housework feel less supported by their spouses/partners for paid work. Fathers who do more of the housework feel more supported by their spouse/partner. Again these findings suggest a gender influence. That is to say, housework appears to have a different meaning depending on the gender of the parent. One might even go as far to say that for mothers housework is a demand that has a direct impact on family–work conflict. For fathers, housework functions more like a resource. The more the father does housework, the more he earns support from his spouse. We suggest one cautionary note: The relationship between housework and spouse/partner support for paid work is not significant in the multivariate analyses for either mothers or fathers.

We make one additional observation of the data in this study. With the exception of the resource variable spouse/partner’s childcare involvement, none of the demand or resource variables were significantly related to mothers’ perceptions of spouse/partner support for paid work in the final model of the multivariate analysis. In contrast, fathers’ sense of support from spouses/partners appeared to be more sensitive to several demand/resource variables. Three variables stand out as being significantly related to fathers’ reports of spouse/partner support for paid work in the multivariate analysis—being an African-American parent, number of preschool children in the family, and spouse/partner’s job flexibility. These findings may suggest that fathers’ perceptions of support for work from spouses/partners are more sensitive to ecological factors than are mothers’ perceptions of support. In the same way that fathers’ parenting may be more sensitive than mothers’ parenting to contextual factors (Doherty et al., 1998), fathers’ perceptions of support for work from mothers may be more context-sensitive than mothers’ perceptions of support from fathers.

There are several significant limitations to the data in this study. First, the sample was not representative of the larger population. The families in the present study were mostly well-educated, white, and middle income. It is therefore not possible to generalize the findings to other parents. Second, the data cannot be used to establish cause–effect relationships. For example, one cannot conclude that fathers’ childcare involvement causes mothers to feel greater spouse/partner support for paid work. Conceivably, mothers’ perceptions of support may influence fathers to be more responsible for children in childcare. Another limitation is the small sample size. Several demand or resource variables may have reached significance in relation to the dependent variable if a larger sample was used.

Despite the limitations of the present data, the findings of the current study suggest the need for continued research on the relationship between childcare factors and parents’ family–work conflict. Indeed a growing body of research has revealed significant associations between parents’ childcare resources and their wellbeing. The findings of the present study build on this area of research by pointing to the importance of spouse/partner’s involvement in childcare as a resource to parents in their attempts to manage family–work conflict. The findings of the present study also suggest the need to further examine the influence of gender in relation to family–work conflict. Future research should extend the work of the current study by examining mothers’ and fathers’ gender beliefs in relation to ecological factors and family–work conflict.

References

Adams G., Rohacek M., (2002). More than a work support? Issues around integrating child development goals into the child care subsidy system Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17:418–440

Almeida D. M., Maggs J. L., Galambos N. L., (1993). Wives’ employment hours and spousal participation in family work Journal of Family Psychology 7:233–244

Barnett R. C., (2005). Dual-earner couples: Good/bad for her and/or him? In: Halpern D. F., Murphy S. E., (Eds) From work–family balance to work–family interaction. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, 151–172

Bernhardt E. M., Goldscheider F. K., (2001). Men, resources, and family living: The determinants of union and parental status in the United States and Sweden Journal of Marriage and Family 63:793–803

Bianchi S., Milkie M. A., Sayer L., Robinson J. P., (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor Social Forces 79:191–228

Bronfenbrenner U., (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development American Psychologist 32:513–531

Clark S. C., (2001). Work cultures and work/family balance Journal of Vocational Behavior 58:348–365

Coverman S., Sheley J. F., (1986). Changes in men’s housework and child-care time, 1965–1975 Journal of Marriage and Family 48:413–422

Dilworth J. E. L., (2004). Predictors of negative spillover from family to work Journal of Family Issues 25:241–261

Doherty W. J., Kouneski E. F., Erickson M. F., (1998). Responsible fathering: An overview and conceptual framework Journal of Marriage and the Family 60:277–292

Fagan J., (1997). Patterns of mother and father involvement in day care Child and Youth Care Forum 26:113–126

Fagan J., Palm G., (2004). Fathers and early childhood programs. Delmar Publishing, Clifton Heights, NY

Ferree M. M., (1991). The gender division of labor in two-earner marriages: Dimensions of variability and change Journal of Family Issues 12:158–180

Fox G. L., Murry V. M., (2000). Gender and families: Feminist perspectives and family research Journal of Marriage and Family 62:1160–1172

Gershuny J., Robinson J. P., (1988). Historical shifts in the household division of labor Demography 25:537–553

Greenberger E., Goldberg W. A., Hamill S., (1989). Survey measures for the study of work, parenting, and well-being. University of California, Program in Social Ecology, Irvine, CA

Grzywacz J. G., Almeida D. M., McDonald D. A., (2002). Work–family spillover and daily reports of work and family stress in the adult labor force Family Relations 51:28–36

Grzywacz J. G., Marks N. F., (2000). Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 51:111–126

Hammer L. B., Allen E., Grigsby T. D., (1997). Work–family conflict in dual-earner couples: Within-individual and crossover effects of work and family Journal of Vocational Behavior 50:185–203

Henly J. R., Lyons S., (2000). The negotiation of child care and employment demands among low-income parents Journal of Social Issues 56:683–705

Hill E. J., Hawkins A. J., Ferris M., Weitzman M., (2001). Finding an extra day a week: The positive influence of perceived job flexibility on work and family life balance Family Relations 50:49–54

Hochschild A. R, Machung A., (1989). The second shift. Avon Books, New York

Madsen S. R., (2003). The effects of home-based teleworking on work–family conflict Human Resource Development Quarterly 14:35–58

McBride B. A., Rane T. R., (1997). Role identity, role investments, and paternal involvement: Implications for parenting programs for men Early Childhood Research Quarterly 12:173–197

Milkie M. A., Peltola P., (1999). Playing all the roles: Gender and the work–family balancing act Journal of Marriage and Family 61:476–490

Perry-Jenkins M., Repetti R. L., Crouter A. C., (2000). Work and family in the 1990s Journal of Marriage and Family 62:981–998

Pleck J. H., (1993). Are “family supportive” policies relevant to men? In: Hood J. C., (Eds) Men, work, and family. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, 217–237

Press, J., Fagan, J., & Bernd, E. (2006). Child care, work, and depressive symptoms among low-income mothers. Journal of Family Issues, 27(5):609–632.

Risman B. J., (1989). Can men “mother”? Life as a single father In: Risman B. J., Schwartz P., (Eds) Gender in intimate relationships. Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont, CA, 155–164

Rutter V., Schwartz P., (2000). Gender, marriage, and diverse possibilities for cross-sex and same-sex pairs In: Demo D. H., Allen K. R., Fine M. A., (Eds) Handbook of family diversity. Oxford University Press, New York, 59–81

Shelton B. A., (1992). Women, men, and time: Gender differences in paid work, housework, and leisure. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT

South S., Spitze G., (1994). Housework in marital and nonmarital households American Sociological Review 59:327–347

U.S. Census Bureau (2002). Who’s minding the kids? Grandparents leading child-care providers, Census Bureau Reports. Retrieved August 17, 2004, from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/2002/cb02-102.html

Voydanoff P., (2004a). The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation Journal of Marriage and Family 66:398–412

Voydanoff P., (2004b). The effects of work and community resources and demands on family integration Journal of Family and Economic Issues 25:7–23

West C., Zimmerman D. H., (1998). Doing gender In: Myers K. A., Anderson C. D., (Eds) Feminist foundations: Toward transforming sociology. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, 167–190

Westman M., Etzion D., (1995). Crossover of stress, strain and resources from one spouse to another Journal of Organizational Behavior 16:169–181

Wiersma U. J., van den Berg P., (1991). Work-home conflict, family climate, and domestic responsibilities among men and women in dual-earner families Journal of Applied Social Psychology 21:1207–1217

Wolfe B., Scrivner S., (2004). Child care use and parental desire to switch care type among a low-income population Journal of Family and Economic Issues 25:139–162

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Press, J., Fagan, J. Spousal Childcare Involvement and Perceived Support for Paid Work. J Fam Econ Iss 27, 354–374 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-006-9009-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-006-9009-8