Abstract

Mainland China has been embarking on a nation-wide education reform as part of its modernisation project for the past few decades. A relatively under-researched topic is teacher agency in non-elite schools where educators critically shape their reactions to new situations brought about by the reform. Focussing on the introduction of school-based curriculum in China, this article discusses how some educators from non-elite schools respond strategically to new opportunities and resources by promoting indigenous knowledge via engaging teaching methods. The essay illustrates, through two examples, how non-elite schools seek to provide the best kind of education available to their students by integrating Confucian and ethnic cultures into the formal curriculum. China’s experience demonstrates the exercise of teacher agency that arises from the interplay of human efforts, available capital and contingent factors. It also highlights the potential of utilising indigenous sources and synthesising them with non-local sources as part of implementing education reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Education reform is increasingly common place among countries in their quest to prepare their graduates for the challenges of a globalised world. China, like other developing countries, has been reforming its education system for the past few decades as part of its modernisation project. The current reform in mainland China, known as the ‘New Curriculum Reform’ (xin kegai) (hereinafter NCR), aims to nurture the inquiring, innovative and collaborative abilities of students under the banner of ‘quality-oriented education’ (suzhi jiaoyu).

To date, there is an impressive body of literature on the processes, tensions, challenges and achievements of the NCR (e.g. see Hannum and Park 2007a; Jin 2007; Wu 2007; Cai and Jin 2010; Ryan 2011; Xie et al. 2010; Jin 2011; Law 2011; Law and Li 2013; Wang and Xiong 2013; Yang 2014; Tan 2013, 2015, 2016; Tan and Chua 2015). But what remains relatively under-explored is the role of teacher agency in non-elite schools where educators critically shape their responses to new situations brought about by the reform. To be sure, a number of researchers have examined the reform experiences of non-elite schools in China by studying the problems, challenges and deprivation faced by educators, students and parents in low-performing rural and migrant schools (e.g. Li et al. 2007; Hannum and Park 2007b; De Brauw and Rozelle 2007; Chen and Liang 2007; Postiglione 2007; Wu 2010; Yao and Xu 2014). However, a tendency in these publications is to emphasise, advertently or inadvertently, the passivity of the educators in these schools by portraying them as recipients or victims of unequal educational opportunities, resources and outcomes. Hong (2015)’s research, although focusing on agency, centres on teacher agency in implementing English as a Foreign Language (EFL), and not the agency exercised by teachers and schools leaders in response to the NCR. More research is needed on how educators in under-privileged schools assume the role of active agents by interpreting and exploiting the new opportunities and resources offered to them under the current education reform in China.

This article discusses how educators in non-elite schools in China exercise their agency by responding strategically to the NCR in their implementation of school-based curriculum. The data for this paper were derived from document analysis, lesson observations and semi-structured focus group interviews conducted with 18 teachers from four non-elite public schools in Beijing between December 2013 and January 2014. Beijing has been selected as the research site as it is one of the leading localities in China in implementing the NCR. In addition, Beijing offers potential rich research data, given its plurality in terms of locality (urban versus rural), type of educational institutions (high-performing versus low-performing) and profile of teachers and students (locals versus migrants) etc.

The four schools selected for our study are non-elite schools (two primary and two secondary) i.e., they are not brand-name schools that produce top scorers on high-stakes examinations. Of the four schools, three are urban schools from two districts while the fourth is a rural school from another district in Beijing. Each of the four schools except one admit students who are mostly Han Chinese (the majority in China); the exception is a primary school that is populated by the country’s minorities especially the Hui ethnic group who are predominantly Muslims. A commonality among the four schools, apart from their shared non-elite status, is their enthusiastic conceptualisation and implementation of school-based curricula. During the interviews, the teachers were asked about their experiences and strategies adopted in implementing the school-based curriculum in their schools. The interviews which were conducted in Mandarin (Putonghua) were audio-recorded with the permission of the interviewees and subsequently transcribed and translated. Unless otherwise indicated, all interviews were conducted in confidentiality and the names of interviewees were withheld by mutual agreement.

The first part of the paper introduces the concept of agency, followed by a brief discussion of China’s current education reform with a focus on school-based curriculum. The next section is devoted to a discussion of the responses, intentions, choices and strategies taken by educators from four non-elite schools in China.

The concept of agency

Policies, as Ball (1998) rightly points out, are both systems of values and symbolic systems: not only do they represent and account for political decisions and seek to achieve material effects, they also serve to legitimate political decisions and manufacture support for the material effects intended by the policymakers. Far from being well-planned, neat and logical, most policies “are ramshackle, compromise, hit and miss affairs, that are reworked, tinkered with, nuanced and inflected through complex processes of influence, text production, dissemination and, ultimately, re-creation in contexts of practice” (ibid., p. 126). An integral part of policy making are the agents that interpret, implement, react to and re-shape the policy.

Agency essentially refers to the capacity of actors to “critically shape their responses to problematic situations” (Biesta and Tedder 2006, p. 11). The exercise of human agency is “about intentional action, exercising choice, making a difference and monitoring effects” (Watkins 2005, p. 47; cited in Frost 2006, p. 21). Agency involves the attempt to make a difference by monitoring the activities of oneself and others in the regularity of day-to-day conduct (Giddens 1984; Durrant and Holden 2006). Teacher agency is expressed through “human actions, either individually or collectively” that include “teachers’ curriculum work and their understanding of educational purposes” (Root 2014, p. 76). Foregrounding the ecological conditions through which agency is enacted, Biesta and Tedder (2007) explain:

[T]his concept of agency highlights that actors always act by means of their environment rather than simply in their environment [so that] the achievement of agency will always result from the interplay of individual efforts, available resources and contextual and structural factors as they come together in particular and, in a sense, always unique situations (Biesta and Tedder 2007, p. 137, as cited in Priestley et al. 2012a, p. 3).

Among the cultural resources available to agents is indigenous knowledge that encompasses “the common-good-sense ideas and cultural knowledges of local peoples concerning the everyday realities of living” (Dei 2002, p. 4). Such knowledge is “accumulated by a group of people, not necessarily indigenous, who by centuries of unbroken residence develop an in-depth understanding of their particular place in their particular world” (Roberts 1998, p. 59, cited in Dei 2002, p. 5). Put otherwise, indigenous knowledges arise from and evolve through a long history shared by a group of people who have consequently derived a distinctive identity of their own. Agency is exercised through indigenisation where individuals select the components of non-indigenous sources that can be integrated with, or replace, existing local historical and socio-cultural practices (Yan 2013; Yang 2005).

The interaction between agency and context entails that “humans do not simply act according to some predetermined pattern, but rather each action is influenced by a range of norms, traditions, overt formalised rules, and so on” (Frost 2006, p. 23). Root (2014) observes that social and cultural restraints “may limit the degree of human agency that individual or group may perceive to be possible” (p. 76). Circumscribed by the prevailing ecological conditions, various agents critically shape their responses to changing and challenging circumstances. Biesta et al. (2015) maintain that “the achievement of agency is always informed by past experience, including personal and professional biographies; that it is orientated towards the future, both with regard to more short-term and more long-term perspectives; and that it is enacted in the here-and-now, where such enactment is influenced by what we refer to as cultural, material and structural resources” (p. 627). It is important to highlight the multiple ways in which agency is exercised by various educational stakeholders in the entire process of implementing the education reform. Fenwick and Edwards (2010) draw our attention to collective agency and the agency of human and non-human assemblages whereas Priestley et al. (2012b) underscore the reflexive and creative abilities of human beings to counter societal constraints and change their relationships to society.

The new curriculum reform (NCR) and school-based curriculum

Before discussing the NCR, it is helpful to give a brief introduction to the phenomenon of elite and non-elite schools in China. Elite schools are ‘key schools’ (zhongdian zhongxue) in China that admit only about 4 % of the secondary population (mostly from urban areas) but enjoy resources up to double the level of non-key schools (Lewin and Hui 1989). Around 70 % of the student population in key schools is composed of children from high-income households or whose parents are cadre and intellectuals (Cheng 2011). A Chinese educator elaborates on the key differences between elite (key) schools and non-elite (weak) schools:

Not only do key schools attract students, they also attract high-quality teachers to join them. They are also prized and hotly pursued by parents. Weak schools, on the other hand, are neglected, face low student enrolment, are seldom chosen as sites for various educational meetings, are seldom subjected to administrative inspections, are unable to win any prizes for various educational appraisal rankings, lack sufficient educational funding, experience high staff turnover, and are under weak educational management. After such a vicious cycle, the weak schools’ infrastructure and human resources will become weaker and more disadvantaged, and the disparity among schools will become more evident (Cheng 2011, pp. 37–38).

Situated within a prevailing exam-centric culture, non-elite schools face a mammoth challenge in improving their test scores and school reputation. As long as schools in China are primarily measured and assessed based on test scores and college-entrance rates, non-elite schools will always be perceived to be inferior to elite schools and marginalised in society.

NCR

Among the official documents on the education reform in China is a seminal document titled Outline of the Curriculum Reform for Basic Education (Trial) (Jichu jiaoyu kecheng gaige gangyao (shixing), hereinafter ‘2001 document’) (Ministry of Education 2001). Calling for a reorientation of curriculum policy, the NCR aims to effect major shifts in the following dimensions of innovations (Law 2011, p. 166):

-

Approaches to Teaching from didactic and unidirectional approaches to strategies that develop highly self-motivated students who take the initiative in learning, are imbued with values and equipped with learning abilities.

-

Curriculum Contents from complicated, extremely difficult, academic-oriented and outdated materials to contents that emphasise students’ life experiences, scientific experiences, and individual interests and needs.

-

Learning Processes from receptive learning, rote learning and mechanistic training to active participation, inquiry-based learning, data collection, information processing, hands-on experience, ability to construct knowledge, analytical skills, problem-solving, communication and collaboration.

-

Assessment from an assessment system that focuses on selection and an elitist philosophy to one that enhances student learning, develops teachers, and improves teaching.

-

Administration from a centralised system to one that fosters a tripartite relationship among central government, provincial agencies, and schools.

It is noteworthy that the NCR seeks to change the educational paradigm in China from ‘exam-oriented education’ (yinshi jiaoyu) to ‘quality-oriented education’ (suzhi jiaoyu). The former, as the name implies, centres on formal assessment where the focus of teaching and learning is academic excellence in high-stakes exams, especially the gaokao (college entrance exam). A quality-oriented education, on the other hand, aspires to transcend exam concerns to emphasising the students’ holistic development. The goal of NCR, accordingly, is for all schools—elite and non-elite—to develop courses, pedagogies and assessment modes that benefit students not just academically but also morally, culturally, physically and emotionally.

School-based curriculum

The NCR expects all schools to carve out their own niches by designing and carrying out their school-based curricula. The 2001 document underlines the need for schools to implement school-based curriculum that integrates the school’s own tradition and strengths with the students’ interests and needs. The NCR’s policy initiative of school-based curriculum is arguably modelled after the concept of School-Based Curriculum Development (SBCD) in the West, especially those in the United Kingdom and Australia (Keiny 1993; Marsh et al. 1990) (p. 66). A senior Chinese educator acknowledges that the school-based curriculum in China is a ‘borrowed’ concept that “was hardly known to headmasters and teachers in China at the beginning of the recent curriculum reform” (Wang 2012, p. 11).

Underpinning the school-based curriculum is a call for schools to identify and develop their special characteristics. Such an endeavour requires schools to create their own niches in accordance with their historical traditions and current situation so as to maximise their students’ potentials and raise the school’s profile in society. The desired outcome is for schools in China to move away from the current homogeneity and uniformity in favour of greater diversity and innovation. Such an outcome would in turn support the policy of ‘school choice’ where parents are encouraged to select a school based on its unique features, strengths and identities. This point is noted by a teacher from a non-elite school:

In recent years, our district educational department has been promoting the message that ‘every school is exciting, everyone is successful’ (xiaoxiao jingcai, renren chenggong). Not every school needs to be a model school or famous school, but it should have its own characteristics, own highlights, areas that are liked by the masses. This has prompted various schools to independently reflect on their school management. Consequently, every school has constructed its own original special curriculum structure (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

The policy intent for schools to develop their own special characteristics is not new as it was mentioned back in a 1993 document, Synopsis of the Educational Reform and Development in China. However, the policy was not successfully implemented in the 1990s as the centralised curriculum management system restricted the schools’ autonomy, resulting in superficial and short-lived policy implementation. So weak were schools in developing their own school-based curricula at that time that some local educational departments even had to step in to help schools ‘discover’ their special characteristics and programmes for the sake of policy execution. A major change between the 1990s and now is that the school-based curriculum under the NCR is situated within a more decentralised school management system where schools are given more freedom and resources to identify and showcase each school’s unique conditions and strengths.

The introduction of school-based curriculum that aims to bring out the school’s special characteristics means that every school, whether elite or otherwise, has the opportunity to carve out a niche and make itself stand out from the rest in the district, province/city and even country. By making the implementation of school-based curriculum mandatory, schools now have to compete not just on the basis of their exam scores and college-entrance rates but also the school’s special characteristics; the objective is to introduce and highlight the different choice schools to parents and students. A teacher explained:

Schools can no longer claim that they cannot perform or have unique characteristics. In actual fact, every school is now striving to develop its unique characteristics and therefore the school principals are under a lot of pressure. The schools need to have a five-year plan, or an even longer period of planning. Therefore, what we need to do is to work out a unique characteristic for our school in the next five years, so that our school can become well-known or popular in the district and the city (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

The policy initiative of school-based curriculum particularly benefits the non-elite schools as they now have a state-sanctioned avenue to excel beyond the traditional platform of high-stakes exams. The policy of school-based curriculum therefore gives the non-elite schools an opportunity to display their capabilities and talents in non-academic domains and consequently improve their standing in society. It is therefore pertinent to explore the agency of educators in non-elite schools, i.e., their intentional actions and choices exercised in the hope of making a difference (Watkins 2005) through their implementation of school-based curriculum. The next section describes the school-based curricula and special characteristics of two non-elite schools.

Example 1: Traditional Chinese culture

The first example is a non-elite school that has distinguished itself in its school-based curriculum that specialises on traditional Chinese culture. Known as the School-based curriculum on the essence of Chinese national culture, this school-based curriculum is part of the ‘national learning’ (guoxue) and ‘back to tradition’ movement in China that promotes traditional Chinese/Confucian culture. This course was popularised by prestigious universities such as Beijing University through its guoxue classes as well as a prime-time programme where Confucian scholars expound on classics such as Confucius’ Analects (Yu 2008). The ‘national learning’ fever has since spread to the schools under the auspices of the Ministry of Education; this is evident, for example, in a 2004 document titled Implementation outlines for education in Chinese national spirit in primary and secondary schools where guoxue and the ‘back to tradition’ movement were lauded (ibid.).

The teacher in charge of the school’s school-based curriculum commented how the school’s niche in ‘national learning’ has helped to build up its reputation, despite the fact that the school is not an elite school:

The main reason for teaching and instructing this school-based curriculum is that we want to establish our own unique school feature. This is because ours is a medium-small scale school, unlike those very well-known large-scale schools which enjoy higher popularity. … Our school principal has also done planning in this respect in all the big-scale and small-scale meetings, and her efforts were recognised by some of the experts from the district and the city. … Through these, our school has enjoyed an elevated status in the hearts of the parents. It also allows the school to gain the parents’ approval of this course, and that they have become very willing to support the development of this course. Therefore, we feel that we have gained a great deal in this respect (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

The school-based curriculum has also been well-received by the students who find the learning interesting without the stress of homework and exam. A teacher who teaches the course noted:

I feel that the children love to attend the lessons. For example, we were not supposed to have a period of national Chinese cultural lesson today. Originally, this period should be English lesson. The children were very excited when they knew about this extra lesson. They felt especially good and happy to attend the national Chinese cultural lesson, and hence looked forward to attend it. This is because the richer and more varied a course is, the more a child would be interested to attend the course, as opposed to attending another boring class lesson (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

The school-based curriculum has received much publicity in the district and was even reported in national newspapers such as Renmin Daily. According to the teacher in charge, the school was motivated to launch this course as “it will allow the children to feel a kind of richness and abundance of the Chinese culture as well as express explicitly the Chinese traditional virtues” (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

There are four types of courses in the school’s school-based curriculum on Chinese national culture, namely, ‘Reading of the classical texts’, ‘Chinese arts’, ‘Practices of tea arts’, and ‘Ceremonial and propriety course’. The first course introduces Confucian classics such as Mencius, Analects, and Doctrine of the Mean to the students. The purpose, as stated by the teacher in charge, is as follows:

Through this course, we mainly want to let the students read the contents of some ancient Chinese proses and classical texts, so that they become receptive to the nurturing and learning of Chinese traditional culture, and also to inherit the Chinese traditional virtues. This is also to allow the students to obtain a feeling of the long history of the Chinese civilisation, which in turn will bring about a sense of self-pride, national pride, as well as a sense of a kind of national spirit of belonging to the Chinese nation (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

The second course, ‘Chinese arts course’, consists of both compulsory and elective subjects. The compulsory subjects are offered to all students from primary 1. They include subjects such as Art which is part of the national curriculum, and Writing which is part of the provincial/district curriculum. Students taking these compulsory subjects learn about traditional culture through appreciating Chinese art and Chinese writing. The elective subjects, on the other hand, are advanced courses meant for students from primary 3 to 6. There are four courses under the ‘roaming class’ (zouban ke) system where students are free to ‘roam’ or join any class based on their selected courses: Chinese calligraphy, Chinese painting, Chinese chess, and zither.

The third category is ‘Practice of tea arts’ where students learn about the history of Chinese tea culture and tea ceremony performances. Finally, the fourth course is ‘Ceremonial and propriety course’ where students participate in ancient rites and ceremonies such as celebrating the birthday of Confucius on September 28th. There are also excursions for students such as the ‘Worship of Confucius Ceremony’ where they visit the Confucius Temple and the Imperial College in Beijing.

The school also consciously infuses moral values through the teaching of Chinese culture. As illustrated by a teacher:

I would choose a good number of public-interest advertisements when I am teaching the topic of integrity from a classical text. There is one particular advertisement, for example, which shows a piece of paper being crumpled and then straightened out again. This is to bring across the message that integrity is just like this piece of paper: no matter how hard you try to straighten it out, it will not work. This is to tell students the importance of integrity. It is during this process that students gain an understanding of the text, and it’s easier for them to comprehend (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

Overall, this school is able to position and market itself as a bastion of Chinese culture and a transmitter of moral values—qualities that are attractive to Chinese parents in choosing a school. The school is also pragmatic enough to ensure that its academic results and school ranking in the district do not slide, and that the students’ academic results will not be adversely affected due to the extra time needed to learn Chinese culture. Hence, despite the fact that the school is not an elite school, the school is able to gain a good reputation in the locality. This point has been noted by a teacher:

This course does not clash with the national curriculum. It does not affect the offering of any national curriculum subjects. We also do not give homework. Actually, it is to let the child experience changes in his behaviour and mannerisms during the process of learning, and the parents are also quite in favour of it. … Actually, many of these parents are willing to let their children have some exposure to Chinese culture. It is because this group of parents is, in many respects, not very well-versed in literature. When the parent tries to educate and interact with his child, he will more or less notice the changes in his child. Hence he is quite in favour of having this type of subject in the school (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

Example 2: Ethnic culture

The second example is another non-elite school, this time an ‘ethnic school’ (minzu xuexiao) where around 50 % of its students and staff belong to non-Han ethnic groups. For over 70 years, the school has nurtured more than 14, 700 students from various ethnic groups such as the Hui, Manchu, Mongolian and Uyghur. Currently, its teacher and student population are composed of nine ethnic groups. Aiming to be an “excellent” and “influential” ethnic school in China, the school states on its website that the “biggest change in the new century is to inherit China’s essence of traditional education as well as modernise its school management ideology, educational approach and teaching environment so as to prosper”. The school’s school-based curriculum capitalises on the school’s existing characteristic and strength, as explained by the teacher in charge:

Ethnic culture is a school-based curriculum. Since our school is an ethnic school, we decided to focus on the arts and crafts of ethnic groups. … It combines our school’s special cultural characteristics with the national cultural heritage (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

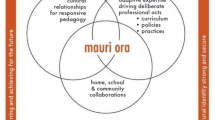

By riding on its existing status as an ethnic school and linking it to the school’s school-based curriculum, the school is able to turn its multi-ethnic composition into a unique selling point. It also judiciously enlists the resources and support of the local authorities and organisations to build up its own brand name. This school has implemented a three-level curriculum that is united by the central theme of ‘ethnic culture’ as follows (Fig. 1):

As noted in the chart above, the core courses are ‘ethnic education’ (minzu jiaoyu) and ‘crafts of ethnic groups’ (minzu gongyi). The former focuses on helping students learn about the history and characteristics of the 56 ethnic groups in China whereas the latter help the students appreciate the diverse cultural manifestations of the ethnic groups. The desired outcome is for students to understand and practise mutual respect, friendship and unity among the ethnic groups. To supplement classroom teaching, the school provides an array of resources such as an ethnic museum in the school compound that displays the cultural artefacts of the 56 ethnic groups in China and a well-stocked library with relevant reading materials. In addition, the school works closely with external organisations such as a nearby mosque that offers guided tours to students, the district’s library that delivers books to students in the school via a mobile library van, and artists who give talks on Chinese ethnic cultures. Furthermore, the school systematically incorporates elements of ethnic culture into various subjects. For example, a music teacher would introduce ethnic songs in class while a Chinese language teacher would share with the students the different writing systems of ethnic groups.

As a school-based curriculum, this course differs from the national curriculum in two main ways. First, students do not need to be formally assessed through any summative and written tests, unlike the core subjects in the national curriculum. Students are instead assessed informally and developmentally through learning and improving at their own pace. Formative assessment rubrics are introduced to assist the teachers to give feedback to the students and their parents on the students’ attitude, values and conduct. A teacher explained:

In terms of appraisal, let’s take for example a child who is relatively weak in using his hands to complete a task. So he may be unable to knead the rice into a proper shape at the beginning. But as he continues to improve himself, he’d be able to compare with himself and improve tremendously. Hence what’s ‘excellent’ to him is different from what’s ‘excellent’ to other children. This allows him to experience success (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

The absence of exam pressure has allowed the teachers to go beyond the confines of the exam syllabus and the relentless pursuit of ‘correct answers’. They are given the autonomy to design and implement interesting and interactive lessons that are aimed at developing the students’ learning abilities and higher-order thinking skills. This is the second difference between the school-based curriculum and the core national curriculum. A teacher elaborated on the pedagogy adopted for a typical lesson:

The primary 4 students are learning about the hats of various ethnic groups this term. So what we’ll do is to plan an activity for students to be acquainted with the topic and then they will find the information themselves. This enables them to gain knowledge on that topic. For example, we first let the students visit our school’s museum to look at the different ethnic hats and choose his favourite hat. He’ll then go online to find out more about the relevant information of that ethnic group. He’ll then share with the class what he has found. Then he’ll make his own ethnic hat using recycled materials so that he’ll learn about environmental protection. He’ll then give a report on his research, both individually as well as in a group (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

The above-mentioned was a major shift from the didactic pedagogy that was the dominant teaching method prior to the 2001 curriculum reform. A teacher said:

Take today’s lesson. In the past the teacher would directly teach the students about the origin, categories and models on the topic. But now, the students need to select appropriate information themselves. Doing so helps to develop the students’ autonomous thinking in the process of selection so that they’ll have their own thinking (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

Another teacher added that whereas the Art teacher in the past only needed to focus on the technique of drawing, he/she now has to achieve four instructional objectives, namely, appreciative commentary, modelling presentation, integrated exploration, and design application. The change in teaching approach is welcomed by the students, as observed by a teacher:

The engaging nature and mode of delivery for this course has been well-received by the students. Students I spoke to shared about their enthusiasm in attending the lesson and knowledge gained through interesting and hands-on activities. Teachers also noted the passion and active participation in the students. One teacher observed, “No need to take exam so students are more enthusiastic about this course and are willing to proactively complete all sorts of activities” (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

A more learner-centric pedagogy has especially helped students who are usually inattentive in class. A teacher commented:

Take for example the boy who narrated the story in a lesson today. He’s actually quite a naughty boy. But he’s willing to volunteer to tell the story today, and he did it so well (interview on 2 Jan 2014).

Similar to the school in Example 1, this school is careful not to neglect the academic performance of the students on high-stakes exams. Rather than replacing the exam subjects with non-examined ethnic-based knowledge and skills, the school complements the latter with the former, thereby adding value to the students’ learning and differentiating itself from other schools that lack such a special curriculum.

What is common for the school-based curricula in the non-elite schools covered in this study is a shift from a predominantly didactic and exam-focused pedagogy to more student-centric teaching approaches. The educators in non-elite schools exercise their agency by experimenting with new pedagogies that engage the students. For example, a teacher in a non-elite school (not from the two schools discussed earlier) said:

I design lessons that the students enjoy and find interesting. For example, I would use some artefacts, pictures, video clips. I would also include some activities, such as getting students to act out a script or something experiential, such as perspective taking where I would ask them, if you were the emperor, what would you have done. All these are to stimulate their interest (interview on 3 Jan 2014).

Added a teacher in another non-elite school:

I would take them to the laboratory to look at some samples and test equipment as they are especially interested in them. For things that they cannot see such as microorganism, I would show them video clips. Basically I aim to arouse their interest, for them to learn, to ask questions from their daily life that relates to biological knowledge (interview on 3 Jan 2014).

Discussion

The exercise of teacher agency in non-elite schools, supported by the ecological conditions under the NCR, has resulted in improving the total learning experiences of students in these schools. This does not mean that non-elite schools have surpassed the elite schools in terms of social perception and status. Despite over a decade of efforts to de-emphasise an exam-oriented education under the NCR, an exam-centric culture still prevails in China. Such a culture means that the school-based curriculum, whether it is the learning of traditional Chinese culture or ethnic culture, will always be perceived to be less important than the mastery of academic contents that are tested in high-stakes exams. In this sense, the contextual and structural factors continue to restrain the agency of educators in non-elite schools and limit their ability to transcend an exam-oriented education that privileges a high college-entrance rate. Given that non-elite schools generally lack sufficient educational funding, experience high staff turnover, enrol students who are academically weak, and are under weak educational management (Cheng 2011), they cannot compete with elite schools on a level playing field in the high-stakes exams. As long as ‘good education’ is interpreted as academic excellence by the majority of the educational stakeholders in China, non-elite schools in China will always lag behind and be viewed as inferior to the elite schools.

But the limited success of the school-based curriculum to challenge the entrenched exam-centric culture in China does not mean that the educators in non-elite schools are passive or bereft of agency in effecting change. As noted earlier, the NCR, with its goal of holistic education, has redefined ‘good education’ in China to encompass not just academic accomplishment but also development in other domains such as morality, sports and arts. The policy initiatives under the NCR have resultantly entrusted all schools with the responsibility to offer a broad-based curriculum that adds value to their students’ learning.

A prominent feature of the exercise of teacher agency in non-elite schools, as this article has pointed out, is the promotion of indigenous knowledge through the school-based curriculum. As noted earlier, such knowledge refers to the tradition, culture and way of life shared by a group of people who have acquired a distinctive identity of their own in the world. The indigenous knowledge, in the case of China, includes Confucian and ethnic cultures that have dominated and shaped the historical and socio-cultural landscape of China for millennia. Given that teacher and school agency have to be related to judgements about the best kind of education that could be made available to students, the educators in non-elite schools view the acquisition of traditional values and practices as an integral part of good education. Their desire to propagate China’s indigenous knowledge is exemplified in the objective of a non-elite school “to allow the students to obtain a feeling of the long history of the Chinese civilisation, which in turn will bring about a sense of self-pride, national pride, as well as a sense of a kind of national spirit of belonging to the Chinese nation” (interview on 2 Jan 2014, cited earlier). In the course of championing indigenous knowledge, these educators go beyond narrow academic pursuit under an exam-centred educational paradigm to develop well-rounded students who are grounded in their own cultural tradition, values and way of life. This goal of holistic education is achieved by drawing upon available historical and socio-cultural resources and incorporating them into the formal curriculum. In other words, educators in non-elite schools exercise their agency by integrating indigenous sources (Confucian and ethnic cultures) with non-indigenous sources, i.e., the modern educational system and its accompanying educational theories and practices in China that were borrowed from elsewhere, especially Russia and the US (for a history of the evolution of China’s educational system, see Tan 2016).

The endeavour of non-elite schools to propagate indigenous knowledge through the school-based curriculum is significant as it has been observed that China has borrowed educational policies from elsewhere, especially Anglophone countries to such an extent that indigenous thought and practices are neglected. Yang (2005), for example, posits, “In retrospect, within the past century in educational research, indigenous Chinese wisdom and the imported western knowledge have never been on an equal footing” as “the western experience that has always been the dominant” (p. 74). Another Chinese scholar calls for indigenousness where educational ideas and methods that manifest “consistency with our origins” should be adopted in China (Lu 2001, pp. 251–252, cited in Yang 2005, pp. 69–70). The promotion of indigenous knowledge through the school-based curriculum therefore demonstrates the agency of educators in non-elite schools to synthesise their reflections on the local culture and history with their approaches to education reform in ways that benefit Chinese culture as well as their schools.

Conclusion

This paper highlighted the role of teacher agency through the intentional action and exercise of choice by educators in non-elite schools. It discussed the active roles of agents—in this case, educators from non-elite schools—in responding strategically to the opportunities and resources available to them under China’s current education reform. China’s implementation of school-based curriculum demonstrates the achievement of agency that arises from the interplay of human efforts, available capital and contingent factors. At the same time, it brings attention to the reality that actors always act by means of their environment under the influence of socio-cultural constraints. China’s experience further suggests indigenous knowledge as a potential source of historical and socio-cultural resources for agents to effect change by integrating local and foreign ideas and practices.

References

Ball, S. J. (1998). Big policies/small world: An introduction to international perspectives in education policy. Comparative Education, 34(2), 119–130.

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 624–640.

Biesta, G. J. J., & Tedder, M. (2006). How is agency possible? Towards an ecological understanding of agency-as-achievement. Working paper 5, Exeter: The Learning Lives project.

Biesta, G. J. J., & Tedder, M. (2007). Agency and learning in the lifecourse: Towards an ecological perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 39, 132–149.

Cai, B., & Jin, Y. (2010). Realistic circumstances and future choices of reforms in basic education in China. Journal of Shanghai Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 39(1), 92–102. (in Chinese).

Chen, Y. P., & Liang, Z. (2007). Educational attainment of migrant children: The forgotten story of China’s urbanisation. In E. Hannum & A. Park (Eds.), Education and reform in China (pp. 117–132). Oxon: Routledge.

Cheng, Z. (2011). Jiaoyu gongping lunshu yu Zhongguo jiaoyu zhengce zhi yanjiu—yi Hunan jiaoyu qiangshen zhengce weili [Research on discourse in educational fairness and educational policy in China—Using the example of educational strengthening of the provinces in Hunan]. (Unpublished master’s thesis). National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University.

De Brauw, A., & Rozelle, S. (2007). Returns to education in rural China. In E. Hannum & A. Park (Eds.), Education and reform in China (pp. 207–223). Oxon: Routledge.

Dei, G. J. S. (2002). Rethinking the role of indigenous knowledges in the academy. NALL working paper # 58. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

Durrant, J., & Holden, G. (2006). Teachers leading change. London: Paul Chapman.

Fenwick, T., & Edwards, R. (2010). Actor-network theory in education. London: Routledge.

Frost, D. (2006). The concept of ‘agency in leadership for learning. Leading and Managing, 12(2), 19–28.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hannum, E., & Park, A. (2007a). Academic achievement and engagement in rural China. In E. Hannum & A. Park (Eds.), Education and reform in China (pp. 154–172). Oxon: Routledge.

Hannum, E., & Park, A. (Eds.). (2007b). Education and reform in China. London: Routledge.

Hong, Y. (2015). Teacher mediated agency in educational reform in China. Dordrecht: Springer.

Jin, S. (2007). Curriculum reform: A major project that cannot be accomplished in a hurry. In Q.-Q. Zhong & G.-P. Qu (Eds.), Reflections on education in China (pp. 136–140). Shanghai: East China Normal University Press. (in Chinese).

Jin, X. (2011). Shinian kegai: gaide zenyang? [Ten years of curriculum reform: What is the outcome?]. Guangming Ribao. Retrieved from http://news.guoxue.com/article.php?articleid=29420.

Keiny, S. (1993). School-based curriculum development as a process of teachers’ professional development. Educational Action Research, 1(1), 65–93.

Law, E. H. (2011). School-based curriculum innovations: A case study in mainland China. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(2), 156–166.

Law, H.-F. E., & Li, C. (Eds.). (2013). Curriculum innovations in changing societies: Chinese perspectives from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Lewin, K., & Hui, X. (1989). Rethinking revolution; reflections on China’s 1985 educational reforms. Comparative Education, 25(1), 7–17.

Li, W., Park, A., & Wang, S. (2007). School equity in rural China. In E. Hannum & A. Park (Eds.), Education and reform in China (pp. 27–43). Oxon: Routledge.

Lu, J. (2001). On the indigenousness of Chinese pedagogy. In R. Hayhoe & J. Pan (Eds.), Knowledge across cultures: A Contribution to dialogue among civilisations (pp. 249–253). Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, Comparative Education Research Centre.

Marsh, C., Day, C., Hanney, L., & McCutcheon, G. (1990). Reconceptualising SBCD. London: Falmer Press.

Ministry of Education (2001). Notice of the issuance of ‘basic education curriculum reform programme (Trial)’ by the ministry of education (in Chinese). Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2002/content_61386.htm/.

Postiglione, G. A. (2007). School access in rural Tibet. In E. Hannum & A. Park (Eds.), Education and reform in China (pp. 93–116). Oxon: Routledge.

Priestley, M., Biesta, G. J. J. & Robinson, S. (2012) Teachers as agents of change: An exploration of the concept of teacher agency. Working paper. http://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/9266/1/What%20is%20teacher%20agency-%20final.pdf.

Priestley, M., Edwards, R., Priestley, A., & Miller, K. (2012b). Teacher agency in curriculum making: Agents of change and spaces for manoeuvre. Curriculum Inquiry, 43(2), 191–214.

Roberts, H. (1998). Indigenous knowledges and Western science: Perspectives from the Pacific. In D. Hodson (Ed.), Science and technology education and ethnicity: An Aotearoa/New Zealand perspective. Proceedings of a conference held at the Royal Society of New Zealand, Thorndon, Wellington, May 7–8, 1996. The Royal Society of New Zealand Miscellaneous Series #50.

Root, D. (2014). Debunking the myth of standardised education to promote equity and rigour. In A. T. Costigan & L. Grey (Eds.), Demythologising educational reforms: Responses to the political and corporate takeover of education (pp. 68–86). New York: Routledge.

Ryan, J. (2011). Introduction. In J. Ryan (Ed.), Education reform in China: Changing concepts, contexts and practices (pp. 1–17). Oxford: Routledge.

Tan, C. (2013). Learning from Shanghai: Lessons on achieving educational success. Dordrecht: Springer.

Tan, C. (2015). Education policy borrowing and cultural scripts for teaching in China. Comparative Education, 51(2), 196–211.

Tan, C. (2016). Educational policy borrowing in China: Looking west or looking east? Oxon: Routledge.

Tan, C., & Chua, C. S. K. (2015). Education policy borrowing in China: Has the West wind overpowered the East wind? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45(5):686–704.

Wang, B. (2012). School-based curriculum development in China: A Chinese-Dutch cooperative pilot project. Enschede: Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development.

Wang, Z., & Xiong, M. (2013). Xin kecheng gaige tuijinzhong cunzai de wenti, chengyin ji duice [The existing problems, causes and strategies in implementing the new curriculum reform]. Jiaoyu Lilun Yu Shijian, 8, 14–16.

Watkins, C. (2005). Classrooms as learning communities. London: Routledge.

Wu, G.-P. (2007). Why be confident about curriculum change. In Q.-Q. Zhong & G. Qu (Eds.), Reflections on education in China (pp. 164–166). Shanghai: East China Normal University Press. (in Chinese).

Wu, D. (2010). Zhongguo jiaoyu gaige fazhan yanjiu [Research on the development of educational reform in China]. Beijing: Jiaoyu Kexue Chubanshe.

Xie, G., Huang, C., & Zhou, S. (Eds.). (2010). Jujiao kegai juesheng ketang: Xin kecheng gaige lunwen huicui [Focussing on curriculum reform for winning classrooms: Essays on the new curriculum reform]. Zhejiang: Zhejiang daxue chubanshe.

Yan, M. C. (2013). Towards a pragmatic approach: A critical examination of two assumptions of indigenization discourse. China Journal of Social Work, 6(1), 14–24.

Yang, R. (2005). Internalisation, indigenisation and educational research in China. Australian Journal of Education, 49(1), 66–88.

Yang, D. (2014). Xinkecheng gaige de deshi he shenhua: jianyu Wang Cesan jiaoshou jiaoliu [The pros, cons and deepening of the new curriculum reform: exchange with Professor Wang Cesan]. Xiandai Jiaoyu Kexue, 6. Retrieved from http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_492471c80102e77a.html.

Yao, H., & Xu, Z. (Eds.). (2014). Zhongguo xibu fazhan baogao [Annual report on development in Western region of China]. China: Shehui Kexue Wenxian Chubanshe.

Yu, T. (2008). The revival of Confucianism in Chinese schools: A historical-political review. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 28(2), 113–129.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, C. Teacher agency and school-based curriculum in China’s non-elite schools. J Educ Change 17, 287–302 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-016-9274-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-016-9274-8