Abstract

In Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese aspectual distinctions are mainly expressed by aspectual adverbs. These adverbs are characterized by their close relation with the lexical aspect of the verb they modify. This paper argues for the existence of an Inner Aspect Phrase within an articulated VP (vP) in Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese which hosts the lexical aspect of the verb. This Inner Aspect Phrase corresponds to an Outer Aspect Phrase outside the VP, which hosts the grammatical aspect. The aspectual adverbs are analyzed as specifiers of the Outer Aspect Phrase. The correspondence of the two Aspect Phrases accounts for the close connection between aspectual adverbs and the telicity features of the verb in Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese. In ancient Chinese aspectual distinctions apparently have been marked by affixation. This morphological system concerns the lexical aspect, the Inner Aspect Phrase, rather than the grammatical aspect, the Outer Aspect Phrase. If this hypothesis proved to be correct, the grammatical aspect would not have been marked in the morphology of the verb at all, but purely by lexical means, i.e., by aspectual adverbs and possibly by sentence-final particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Aspecto-temporal adverbs constitute a closed class in Late Archaic (5th–2nd c. BCE) and Early Medieval Chinese (1st c. BCE–3rd c. CE).Footnote 1 On the one hand they include adverbs which are evidently aspectual such as jì 既 and yǐ 已 expressing completion and the perfective aspect, and cháng 常 and sù 素 expressing different kinds of habitual aspect. On the other hand they include adverbs such as cháng 嘗 and céng 曾 expressing past, and jiāng 將 and qiě 且 expressing future tense (Meisterernst 2004, 2005, 2015a, b). This paper will mainly concentrate on the syntax of the perfective adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已; additionally, it will present a short discussion of the habitual adverbs cháng 常 and sù 素.

All these adverbs, including the seemingly temporal adverbs referring to the past and the future tense, are syntactically distinct from point of time adverbials. For point of time adverbials both the sentence-initial position and the preverbal position are available; frequently the sentence-initial is their default position. In Ernst (2002, p. 328) they are labelled as ‘Loc-Time Adverbials’ and defined as “the clearest cases of mapping to reference-times”; they are relatively free in their distribution. Example (1) represents the point of time adverbial ‘in the night of the day yimao’ referring to a date in sentence-initial, i.e., in topic position.Footnote 2

(1) | 乙卯夜, 棄疾使船人從江上走呼曰 | Shǐjì: 40; 1708 | |||||

Yìmǎo yè, | Qìjí | shĭ | chuán rén | cóng Jiāng shàng zŏu hū | yuē | ||

Yimao night, | Qiji | order boat | man from Jiang above run shout | say | |||

‘In the night of the day yimao, Qiji ordered some boatmen to run along the bank of the Jiang and to shout:…’ | |||||||

In contrast to point of time adverbials, aspecto-temporal adverbs are confined to the preverbal position. In the hierarchical ordering of adverbs they occupy a position below that of point of time adverbials, and also of modal adverbs, but above Aktionsart (Alexiadou 1997) adverbs (like shuò 數 ‘repeatedly’, generated within an articulated VP) and manner adverbs. According to their syntactic position with regard to negative markers, wh-words, and the YI-phrase, they evidently have to be generated outside the articulated VP (the vP) (Meisterernst 2015a, b). Example (2) includes the modal adverb yì 亦 ‘also’, the aspectual adverb sù 素 ‘habitually’, and the Aktionsart adverb shuò 數 ‘frequently’ in the expected order.Footnote 3

(2) | 漢元年二月, 項羽立諸侯王, … 項羽亦素數聞張耳賢, … | Shǐjì: 89; 2580 | |||

Hàn yuán nián èr yuè, | Xiàng Yŭ lì | zhū-hóu | wáng, | ||

Han first | year two month, Xiang yu establish | feudal-lord | king, | ||

Xiàng Yŭ yì | sù shuò | wén Zhāng Ĕr xián, | |||

Xiang Yu moreover SU frequently hear Zhang Er virtuous, | |||||

‘In the first year of Han, in the second month, Xiang Yu installed the feudal lords as kings; … Xiang Yu on his part had repeatedly heard that Zhang Er was virtuous, …’ | |||||

The position of aspectual adverbs with regard to manner adverbs argues for their integration in one semantic super-category which would correspond approximately to the semantic zone of ‘middle aspect’ in Tenny (2000). To a greater extent than point of time adverbials, aspectual adverbs are—to different degrees—characterized by their close relation with the semantics, particularly the aspectual features of the verb. To account for the close correspondence of these adverbs with the lexical aspect of the verb, two aspectual phrases following Travis (2010) will be proposed: an Outer AspectP located within TP, which hosts the aspectual adverbs, and an Inner AspectP, selected by the head of an Outer AspectP, located within a layered VP (vP).Footnote 4 Due to their syntactic position, it will be hypothesized that at least the purely aspectual adverbs such as jì 既 and yǐ 已, which express completion, the resultative, and the perfective aspect, and the adverbs cháng 常 and sù 素, expressing continuous and habitual, and accordingly imperfective aspectual notions, are located in the Outer Aspect Phrase and, more precisely, in the specifier position (see Cinque 1999) of this AspectP. The fact that the position of these adverbs is fixed and that they obviously cannot be freely adjoined to different phrases seems to argue for a specifier analysis and not for an adjunction analysis (see Cinque 1999, p. 133).Footnote 5 The head of the Outer Aspect Phrase, which hosts the grammatical, i.e., the perfective and imperfective aspect, selects an articulated VP containing an Inner AspectP (following Travis 2010); this VP hosts the telicity features, i.e., the lexical aspect, of the verb.Footnote 6 In the default case, the aspectual features of the Outer AspectP, manifested by the adverb in its specifier, correspond to the telicity features of the Inner AspectP; i.e., a [+perfective] AspP hosting the adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已 combines with a VP with corresponding [+telic] features. A [−perfective] AspP with habitual, i.e., [−perfective] adverbs such as cháng 常, correspondingly combines with a [−telic] Inner AspectP. If the telicity features of the VP, i.e., the Inner AspectP, do not coincide with the aspectual features of the Outer AspectP, a coercion effect, namely a situation type shift of the predicate, is induced. Travis (2010, p. 15) presents the following examples to explain coercion:

(3) | a. | We are solving the problem. |

b. | Mary ran in three minutes. |

The appearance of an achievement verb (−process) in the progressive aspect and of an activity verb (−definite/telic) with a time-frame adverbial should be ungrammatical. However, in particular contexts (the process leading up to solving a problem in (3a), or e.g., “doing a morning run” in (3b)), an original achievement or an original activity can behave like an accomplishment due to the coercion effect (Travis, idem). The same effect can be induced by the aspectual adverbs at issue in this paper. Example (4) represents a default situation type reading of the Chinese [+telic] verb bìng 并 ‘unify’ modified by the [+perfective] adverb jì 既; example (5) represents a shifted situation type with the originally [−telic] state verb ān 安 ‘peaceful’ modified by the [+perfective] adverb yǐ 已. The mismatch of a [+perfective] Outer AspP and a [−telic] Inner AspP leads to a situation type shift of the verb from state to event; the predicate receives a [+telic] inchoative reading. This coercion effect provides a particular argument for the close relation between the aspectual properties of the AspP hosting the adverb and the telicity features of the verb; this is best accounted for by two different AspP phrases, one above and one within VP. The coercion effect is constrained by the compatibility of the semantic features of the adverb with the telicity features of the verb the aspectual adverb combines with. If e.g., a [+perfective] adverb combines with a verb that does not permit a change-of-state reading, i.e., a shift from [−telic] to [+telic], the resulting structure becomes uninterpretable.Footnote 7

(4) | 秦始皇既并天下而帝, 或曰: | Shǐjì: 28; 1366 | ||||||||

Qín Shĭ | huáng | jì | bìng | tiānxià | ér | dì, | huò | yuē | ||

Qin First Emperor already unify empire | CON emperor, someone say | |||||||||

‘After the First Emperor of Qin had unified the empire and become emperor, someone said: …’ | ||||||||||

(5) | 成王在豐, 天下已安, 周之官政未次序. | Shǐjì: 33; 1522 | ||||||

Chéng wáng zài | Fēng, tiānxià | yĭ | ān, | Zhōu zhī | guān | zhèng | ||

Cheng king | be.at Feng, empire | already peace, Zhou GEN office government | ||||||

wèi | cìxù | |||||||

NEGasp regulate | ||||||||

‘King Cheng was in Feng, and the empire was already at peace, but the offices and the administration of Zhou had not been regulated yet.’ | ||||||||

1.1 The syntax of aspect according to Travis

In a syntactic approach to the structure of events or situationsFootnote 8 as it has been pursued, for instance, by Ritter and Rosen (2000), Travis (e.g., 2010), and many others, it has been claimed that “Vendler’s predicate classes are represented in a predictable way in the configuration and features of phrase structure” (Travis 2010, p. 93). Travis’s approach is based on the semantic decomposition of event structure proposed e.g., by McCawley (1968), Dowty (1979), and Pustejovsky (1991), in which an event is decomposed into several sub-events. Within this framework, and based on her computation of the Inner Aspect, Travis proposes different representations of Vendler’s four classes within an articulated VP (Travis 2010, p. 119f); in her computation she distinguishes between intransitive and transitive states, and unaccusative and transitive achievements.

Travis’s representation seems to account well for the close relation between the function of the aspectual adverbs generated above the articulated VP and the lexical aspect of the verb in Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese; it also argues for the hypothesis that the aspecto-temporal adverbs are located in an Outer Aspect Phrase which requires an articulated VP with a corresponding Inner Aspect Phrase (Travis 2010, p. 118ff).Footnote 9

(6) | The Event structure following Travis (2010, p. 187): The Outer and the Inner Aspect |

Many accomplishments and transitive achievements require an Agent outside the Inner Aspect Phrase,Footnote 10 which—as the external argument—is merged in [Spec, VP (vP)], i.e., [Spec, V1P], and moves up to [Spec, TP]; in unaccusative achievements, it is the Theme, the internal argument, which assumes the role of the subject.Footnote 11 The DP in [Spec, I(nner)AspP] represents the event measuring DP, i.e., the internal argument; for a theme argument to measure out the event, it has to move up to this position. V1 is assumed to host the feature [+/−process], which can be represented by the light verbs cause in activities and accomplishments, or have in transitive states and transitive achievements (Travis 2010, p. 118f); according to Travis V1 is a lexical category (2010, p. 11). One of the arguments Travis provides for her analysis is the syntactic difference between the l-syntax causative ‘kill’ and the s-syntax causative ‘cause to die’ (Travis 2010, p. 15f), “in the case of the l-syntax causative AspP is selected. In the case of the s-syntax causative, EP is selected.” The difference between the two causatives is represented by the examples (7a–d) (Travis 2010, p. 106).

(7) | a. | John caused the plant to die and it surprised me that he did so. |

b. | John caused the plant to die and it surprised me that it did so. | |

c. | John killed the plant and it surprised me that he did so. | |

d. | *John killed the plant and it surprised me that it did so. |

The addition ‘it did so’ refers to the entire event of the plant dying. This is possible with the ‘caused to die’ construction which selects an entire EP, but not with the ‘kill’ construction which merely selects an Inner AspP.

In favor of complete articulated VP structures for all four aspectual classes, Travis presents an argument from the morphology of a language such as Malagasy (Travis 2010, p. 121). She claims that in Malagasy V1 can be filled by the lexical-causative prefix an- (similar to pag- in Tagalog), or by two other morphemes, the stative prefix a-, and the unaccusative prefix i- as in example (8).

(8) | a. | m-an-√ala | ‘to take out’ | lexical causative |

b. | m-a-√loto | ‘to be dirty’ | stative | |

c. | m-i-√ala | ‘to go out’ | unaccusative |

These prefixes appear between another prefix m-, for which Travis proposes a position in E, and a morpheme—ha—which encodes telicity and appears in the Inner Aspect Phrase. This provides a strong argument for her computation of a layered VP. She gives the following examples for this combination.

(9) | a. | m-an-ha-√rari | ‘sick’ | mankarary | to make sick |

b. | m-a-ha-√ala | ‘to go out’ | mahaala | to be able to take out | |

c. | m-i-ha-√tsara | ‘good’ | mihatsara | to become better | |

(cf. Travis 2010, p. 121) | |||||

If Travis’s hypothesis also accounted for Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese, then V1 would always be zero during this period. In earlier stages of Chinese it might have been the host of some of the aspectual morphology introduced below. Additionally, V1 represents an arbitrary bound, a beginning or a natural endpoint (Travis 2010, p. 244f). The telicity features [+/−telic] which distinguish events from activities and states, are checked in the Inner Aspect Phrase (Travis 2010, p. 118f); V2P is headed by the lexical verb. In general, according to Travis (2010, p. 242) event boundaries can be encoded in three different positions: (1) in the XP as the complement of V2, indicating the natural endpoint, e.g., by a prepositional phrase, (2) in Asp, the telicity position which determines either an ending or a beginning, or (3) in V1, the process position, which determines a final or an initial point or an arbitrary bound to the process. The latter is particularly evident e.g., in the coercion cases of perfective adverbs modifying [−telic] state predicates. To represent a typical change from a [−telic] to a [+telic] predicate by adding a natural endpoint indicated by a PP, Travis chooses an example with the [−telic] verb ‘push’. Because the event measuring DP in (19c) is a bare plural ([−SQA]), it changes the entire situation back to a [−telic] situation (Travis 2010, p. 246).

(10) | a. | push DP sg —atelic |

The children pushed the cart. (*in three minutes/√for three minutes) | ||

b. | push DP sg PP—telic | |

The children pushed the cart to the wall. (√in three minutes/*for three minutes) | ||

c. | push DP barepl PP—atelic | |

The children pushed carts to the wall. (*in three minutes/√for three minutes) | ||

The syntactic analysis presented here is merely supposed to provide a first and general idea about a possible syntactic representation of the position of aspecto-temporal adverbs in Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese; many details and problems with this analysis still have to be worked out. In order to further simplify matters, only a single Outer Aspect Phrase has been assumed in this representation, although it is not clear whether all aspecto-temporal adverbs can be located in the same position in the Outer Aspect Phrase or whether different functional heads—on a par with Cinque’s (1999) proposal—have to be assumed for the different aspectual meanings (see also Meisterernst 2015a, b).

1.2 Aspectual adverbs and the grammatical and lexical aspect (Aktionsart) of the verb

For Modern Mandarin the relevance of the lexical aspect has long been recognized, since it determines—among other syntactic and semantic constraints—the employment of the different aspectual suffixes and, accordingly, many studies have been devoted to this issue. In the following Modern Mandarin example the perfective suffix –le 了 marks a verb with a quantized object, which is [+telic], referring to a situation in the past. This suffix is supposed to have functions similar to those of the aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已 discussed in this paper (see Meisterernst 2005, 2015a, b).

(11) | 我看了這本小說. | ||

Wŏ kàn | le | zhèi bĕn xiăoshuō | |

I | read LE | this MS novel | |

‘I read this novel.’ | |||

In Late Archaic Chinese, the source structures for the aspectual suffixes of Modern Mandarin—one of which is categorized as expressing the perfective aspect—do not yet exist. They only start to develop during the Early Medieval period, maybe due to the loss of a morphological marking of different aspectual notions by affixation. These affixes have been reconstructed on the basis of tone alternations and different initial consonants in Middle Chinese, e.g., the alternation between a [−voice] and a [+voice] initial, and the alternation between any tone (píng, shǎng, rù) and the qùshēng. According to Jin (2006) the first alternation is frequently connected to causation, agentivity, and volition, but also to purely aspectual notions.Footnote 12 , Footnote 13

(12) | Verbs with an alternation between a [−voice] and a [+voice] initial | |||||||

Transitive variant | intransitive, unaccusative (ergative) variant | |||||||

bài | pa | 敗 | destroy | bài | ba | 敗 | destroyed (unaccusative) | |

zhé | t | 折 | break | shé | d | 折 | broken | |

jiàn | k | 見 | see | xiàn |

| 見 | be visible | |

The most prominent of the morphological distinctions, the alternation of tones sì shēng biè yì (e.g., Mei 1980, Sagart 1999, Schuessler 2007), concerns a derivational suffix *-s in Archaic Chinese. This morpheme has been reconstructed as the basis of most qùshēng (Haudricourt 1954) words; it had different, mainly derivational, functions. On the basis of a comparison with the verbal system of Tibetan, it has been hypothesized that one of the functions of this suffix, possibly the basic function in combination with verbs, was to mark the perfective aspect (Unger 1983, No. 20; Jin 2006).Footnote 14 According to Schuessler (2007) “This system constitutes the ‘youngest’ morphological layer which was still productive or at least transparent in OC.”Footnote 15 The alternation of tones is represented in example (13). In (13a) a change of the thematic role of the subject from agent to theme is involved; the qùshēng reading zhì (dri h) additionally refers to the state resulting from the activity or event expressed by chí (dri). In (13b) no change of meaning is recorded; for these verbs Unger (1983) proposes that the qùshēng reading refers to the perfective aspect.Footnote 16 , Footnote 17

(13) | verbs with a qùshēng variant resulting from a reconstructed suffix *s- | |||

(13a) |

chí 治dr

|

zhì治dr

| ||

(13b) | guàn 貫 kwan | versus | kwan h | ‘pass through’, ‘perforate’ |

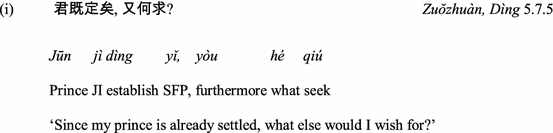

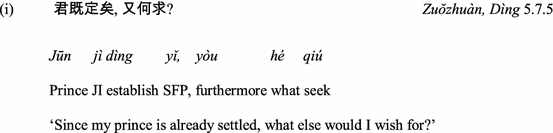

Despite this obvious morphological marking, it is still difficult to determine to which extent it was mandatory in the early stages of the Chinese language. Probably already in Late Archaic, but certainly in Early Medieval Chinese, the aspectual morphology was not productive any longer and only visible by the traces it left in the phonology of the language of the time. In the analyses of the morphological marking by affixation, no distinctions between the grammatical and the lexical aspects have been made in the literature. However, due to the fact that the alternations frequently concern a difference in the telicity features of the verb, the hypothesis has been proposed (Meisterernst 2014, 2015a, b) that the aspectual affixes probably involve the lexical rather than the grammatical aspect of the verb; this would mean that they are generated in the Inner Aspect Phrase within the VP and not in the Outer Aspect Phrase. If this hypothesis proved to be correct, the determination of the grammatical aspect of the predicate generated in the Outer AspP would rather depend on the employment of lexical means. Possible heads of the Outer AspP could be sentence-final particles such as yǐ 矣 and yě 也 (e.g., Pulleyblank 1994, 1995). Aspectual adverbs such as jì 既 ‘already’ and yĭ 已 ‘already’, cháng 常 and sù 素, and the negative marker wèi 未 ‘not yet,’ can occur as additional markers. Both the perfective adverb yǐ 已 and the SFP yǐ 矣 are present in the following example:

(14) | 勃既定燕而歸, 高祖已崩矣,… | Shǐjì: 57; 2071 | ||||||||

Bó | jì | dìng | Yān | ér | guī, | Gāozŭ yĭ | bēng | yĭ | ||

Bo already establish Yan CON return, Gaozu already pass.away SFP | ||||||||||

‘When Bo had pacified Yan and returned, Gaozu had already passed away,…’ | ||||||||||

The telicity features of the verb hosted by the Inner Aspect phrase cease to be marked in Late Archaic Chinese. In Medieval Chinese the source structures of the aspectual suffixes of Modern Mandarin develop possibly due to the loss of aspectual morphology; these are also hypothesized to be located in the Inner AspP.

In this paper, the syntax of the adverbs of the perfective aspect jì 既 and yǐ 已 is discussed in Sect. 2, and that of the adverbs cháng 常 and sù 素 is briefly discussed in Sect. 3. The data is taken from the Han period text Shǐjì (ca. 100 BC).

2 The adverbs of the perfective aspect jì 既 and yǐ 已

The adverbs jì 既 ‘already’ and yĭ 已 ‘already’ at issue in this section have been assumed to express the perfective aspect in Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese (most recently Wei 2015), similar to the perfective suffix—le of Modern Mandarin.Footnote 18 Different approaches have been made to explain the semantic implications of the perfective and the imperfective aspects (e.g., Comrie 1976 and Smith 1997, among many others). Very often, the definition of the two contrasting aspects refers to the respective perspective from which a situation is represented: the imperfective aspect depicts the internal structure of a situation without any focus on either its initial or final boundaries, and is thus compatible with a [−telic] predicate; the perfective aspect views the situation in its entirety from an external perspective, including its initial and its final point; thus it is compatible with a [+telic] predicate.

In an analysis of ‘already’ and related aspectual adverbs in English and other languages, including Chinese, in Ernst (2002, p. 431f), it has been assumed that these adverbs “denote a temporal relation between two events, of which one is linked to reference time, and the other is of the same sort as the first and must have a specific temporal relation to it” (2002, p. 341). As far as their syntax is concerned, according to Ernst (2002, p. 346) “the aspectual adverbs still and already may occur freely in the AuxRange”. As evidence he quotes the ba-construction in Chinese which allows the aspectual adverbs to appear below ba.

(15) | Women ba dianshiji yijing bai-hao-le | |

We ba TV-set already set-good-PRF | ||

‘We already set up the TV set.’ | (cf. Ernst 2002, p. 346) |

According to him, this demonstrates (2002, p. 347) “that UG imposes no strictly syntactic constraint on where aspectual adverbs occur in the AuxRange; when there is no incompatible semantic element preceding them, they may occur even in this very low position”. However, the data in Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese suggest that the aspectual adverbs at issue in this section are subject to different constraints; e.g., they are not permitted in a position below the YI-phrase; this phrase has been analyzed as possessing roughly the same syntactic (and semantic) constraints as the ba-phrase and as being located within the vP (Aldridge 2012).Footnote 19

(16) | 康叔之國, 既以此命能和集其民, 民大說. | Shǐjì: 37; 1590 | |||||||||

Kāng shú zhī guó, | jì | yĭ | cĭ | mìng, | néng hé | jí | qí | mín, | mín | ||

Kang shu go state, already with this mandate can pacify gather his people, people | |||||||||||

dà | yuè | ||||||||||

great happy | |||||||||||

‘Kang shu went to the state, and after he had been able to pacify and settle his people with this mandate, the people were very happy.’ | |||||||||||

As has been demonstrated in Meisterernst (2015a, b), the basic functions of the adverbs jì 既 and yĭ 已 in the language of the Late Archaic and Early Medieval period are:

-

1.

As specifiers of an Outer Aspect Phrase with the characteristic [+perfective] they, by default, modify a VP with a [+telic] Inner AspectP emphasizing a change of state: (a) with telic verbs they emphasize the completion of the event and the final point and the state resulting from the previous event, i.e., they represent the event from a perfective viewpoint; (b) with state verbs they usually emphasize the initial point of the state (inchoative aspect), so the state verb shifts to a [+telic] verb; (c) with an atelic activity verb, they change the situation type of the entire predicate from atelic to telic, and from imperfective to perfective.

-

2.

They emphasize the factual occurrence of an event or a state—frequently with some relevance for the following event. The factuality and the relevance for the following event are particularly evident if the adverbs appear in the protasis of a temporal sentence; this also accounts for the (infrequent) examples in which the perfective predicate refers to a future event.

Abraham (2008) proposes a bi-phasal structure for [+telic] (terminative in his terminology) events, i.e., accomplishments and achievements,Footnote 20 and a mono-phasal structure for [−telic] (non-terminative) non-events, represented by the diagram (17). The bi-phasal structure consists of two events, E1 and E2, referring to the approach/incremental phase and the resultative phase of the event respectively; the mono-phasic structure consists merely of a process or a state phase. In the diagram, t1 refers to the initial point of the incremental phase, tm refers to the initial point of the second, the resultative phase, and tn refers to a final point of the situation. The point tm belongs to both phases.Footnote 21 , Footnote 22

(17) | Event structure following Abraham (2008, p. 7) |

(17a) | event: | | >>>>>>>>> | …………….| | |||

t1 | E1 | tm | E2 | tn | |

既/已 | |||||

(17b) | activity: | (| >>>>>>>>> |) or | |

t1 | E | tn | |

既/已 | |||

(17c) | state: | | ~~~~~~~~~~ | | |

tm | E | tn | |

既/已 | |||

The structure (17a) accounts for terminative (+telic) (in)transitive verbs such as die and kill respectively. Both the external and the internal semantic roles apply to E1, only the internal semantic role applies to E2. The structure (17b) accounts for non-terminative (−telic) (in)transitive verbs such as live and push, respectively. Both the external and internal semantic roles apply to both phases E1 and E2.

According to this structure jì 既 and yǐ 已 mark the change-of-state point tm with event verbs (achievements and accomplishments), the final point tn (and the entire situation) with activity verbs, and the initial change-of-state point tm with state verbs.

2.1 The aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已 with telic verbs

As already stated above, the aspecto-temporal adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已 by default modify telic, mainly achievement verbs. Achievement verbs can be a) genuine intransitive—unaccusative—verbs with a theme subject, verbs such as ‘die,’ etc.; these are true achievements according to the framework adopted in Travis (2010) and others; or b) transitive verbs with an agentive and/or a causative subject and a theme object, frequently the causative variant of an unaccusative verb; these are considered to be accomplishments in Travis’s framework. Their unaccusative variant would be a true achievement. However, telic transitive verbs with an agentive subject which only focus on the final change-of-state point (and the resultant state) are labelled as achievements in other frameworks (e.g., in Smith 1997); this framework will be adopted in the present discussion.Footnote 23 Achievement verbs referring to resultant states differ from genuine states in their telicity features: resultant states with achievement verbs have a [+telic] Inner AspectP and genuine states have a [−telic] Inner AspectP. The examples will be discussed according to their transitivity and to the thematic role assigned to the object and the subject respectively.

-

(a)

Transitive telic verbs (accomplishment and achievement verbs)

Example (18) represents two achievement verbs; the first clause contains an agentive achievement verb marked by jì 既, and the second contains a true achievement according to Travis with a theme subject. In example (19) the verb modified by jì 既, bìng 并 ‘unify’ has an agentive subject; the aspectual adverb does not only have scope over the immediately following verb bìng 并 ‘unify’, but also over the second verb dì 帝 ‘become emperor’, in an inchoative reading (arguing for a generation of the adverb above VP (vP)).Footnote 24 The verb in (20) zhì 至 ‘reach, arrive at’ is a telic motion-to-a-goal verb in a transitive construction.Footnote 25 , Footnote 26

(18) | 勃既定燕而歸, 高祖已崩矣, 以列侯事孝惠帝. | Shǐjì: 57; 2071 | |||||||

Bó jì | dìng | Yān | ér | guī, | Gāozŭ yĭ | bēng | yĭ | ||

Bo already establish Yan CON return, Gaozu already pass.away SFP | |||||||||

yǐ | lièhóu | shì | Xiào Huì dì | ||||||

YI feudal lord serve Xiao Hui emperor | |||||||||

‘When Bo had pacified Yan and returned, Gaozu had already passed away, and he served the emperor Hui of Han as feudal lord.’ | |||||||||

(19) | 秦始皇既并天下而帝, 或曰: | Shǐjì: 28; 1366 | ||||||||

Qín Shĭ | huáng | jì | bìng | tiānxià | ér | dì, | huò | yuē | ||

Qin First Emperor already unify empire CON emperor, someone say | ||||||||||

‘After the First Emperor of Qin had unified the empire and become emperor, someone said: …’ | ||||||||||

(20) | 既至甘泉, 為且用事泰山, 先類祠太一. | Shǐjì: 28; 1396 | |||||||

Jì | zhì | Gān | quán, | wèi | qiĕ | yòng shì | Tàishān, xiān lèi cí | ||

Already reach Sweet Spring, therefore FUT use | affair Taishan, | first sacrifice | |||||||

Tài | Yī | ||||||||

Great One | |||||||||

‘After he reached the Palace of the Sweet Springs, he therefore was on the point of preparing the sacrifices for the Taishan, but first he gave special offerings to the Great One.’ | |||||||||

In all examples jì 既 refers to a perfective situation, i.e., it indicates that the final, the change-of-state point of the event, has been attained and a resultant state obtains. For the semantic relation between the verb and its object, it is irrelevant whether the object is affected and changed, as e.g., with change-of-state predicates with a direct object such as dìng Yān 定燕 ‘settle Yan’, or unchanged as with motion-to-a-goal verbs in VOs such as zhì Gānquán至甘泉 ‘reach the Palace of the Sweet Springs’.Footnote 27 All these objects, whether affected or not, are accusative objects; accusative objects are VP internal and measure out the event (see Travis 2010, p. 11).Footnote 28 They provide the situation with the feature [+definite], the determining feature of a [+telic] event (Travis 2010, p. 10). According to Travis, two features can be distinguished in Vendler’s categorization of predicate classes: the feature “Process is related to durativity while the feature definite is related to telicity.”

The adverb yĭ 已 by default modifies the same kind of telic events as the adverb jì 既. In example (21) the verb shā 殺 ‘kill’, a typical transitive achievement verb, is modified by yĭ 已 in a finite predicate. In example (22) with the verb dìng 定 ‘establish’ the adverb yĭ 已 appears entirely synonymously to jì 既 in a subordinate temporal clause (see ex. (18)).

(21) | 項羽已殺卿子冠軍, 威震楚國, 名聞諸侯. | Shǐjì: 7; 307 | ||||||

Xiàng Yŭ | yĭ | shā qīngzĭ | guānjūn, wēi | zhèn | Chŭ guó, | míng wèn | ||

Xiang Yu already kill honorable general, | might shake Chu state, name make.hear | |||||||

zhū-hóu | ||||||||

feudal-lord | ||||||||

‘Xiang Yu had already killed the Honorable General, his might made the state Chu tremble and his reputation spread to the feudal lords.’Footnote 29

(22) | 李良已定常山, 還報, 趙王復使良略太原. | Shǐjì: 89; 2577 | |||||||

Lĭ Liáng | yĭ | dìng | Chángshān, | huán | bào, | Zhào wáng fù | shĭ | ||

Li Liang already establish Changshan, | return report, Zhao king again send | ||||||||

Liáng lüè | Tàiyuán | ||||||||

Liang ransack Taiyuan | |||||||||

‘After Li Liang had secured Changshan, he came back and reported, and the king of Zhao sent him again to ransack Taiyuan.’ | |||||||||

In example (23) the verb pò 破 ‘destroy’ is modified by yǐ 已 in the clausal complement of the verb wén 聞 ‘hear’; yǐ 已 regularly appears in this position.Footnote 30 Contrastively, jì 既 is—at least with the verbs wén 聞 ‘hear’, zhī 知 ‘know’, and yĭ wéi 以為 ‘regard as, mean’—never attested in clausal complements in the Shĭjì. This fact provides some evidence for the greater syntactic independence of yĭ 已 in early Medieval Chinese in comparison to jì 既.Footnote 31 However, it does not argue for the confinement of jì 既 to events that are known or given information as one of the reviewers suggested. Jì 既 more frequently refers to known and given information, because it appears more frequently in non-finite adverbial subordinate clauses in Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese; these can additionally represent the conditions for the event in the matrix clause. Although jì 既 seems to be confined to the modification of non-finite predication in the early Buddhist literature (Meisterernst 2011), this is not yet the case in a Han period text such as the Shǐjì; in example (24), analyzed as example (29) below, for instance, jì 既 modifies a finite predicate relating an event previously unknown to the hearer. Contrastively to jì 既, yǐ 已 remains to be confined to the purely aspectual functions in the early Medieval literature.Footnote 32

(23) | 又聞沛公已破咸陽, 項羽大怒, 使當陽君等擊關. | Shǐjì: 7; 310 | ||||||

Yòu | wén Pèi gōng yĭ | pò | Xiányáng, Xiàng Yŭ | dà | nù, | shĭ | ||

Again hear Pei duke already destroy Xianyang, Xiang Yu great angry, send | ||||||||

Dāngyáng jūn dĕng | jī | guān | ||||||

Dangyang lord group attack pass | ||||||||

‘When he again heard that the duke of Pei had already destroyed Xianyang, Xiang Yu became very angry and sent the lord of Dangyang and others to attack the pass.’ | ||||||||

(24) | 子之為智伯, 名既成矣. | Shǐjì: 86; 2521 | |||||

Zĭ | zhī | wèi Zhì bó, | míng jì | chéng | yĭ, | ||

You GEN for Zhi earl, name already complete SFP, | |||||||

‘Regarding [the way] you [acted] on behalf of earl Zhi, you already made yourself a name [for it] (lit: your name for it has been completed).’ | |||||||

In examples (18)–(23) jì 既 and yǐ 已 modify transitive verbs with their theme (internal) arguments in object position. Most of these verbs are causative variants of true achievement verbs with theme subjects; these verbs are discussed in the next subsection.Footnote 33 All these verbs can appear as true telic verbs in Late Archaic Chinese; the endpoint does not have to be specified as in Later Stages of Chinese. Although they include a causative sub-event, they only focus on the final point, the become point in V2. Their V1 differs from that of Travis’s transitive achievements; instead of have it rather seems to be cause, but they actually focus on the endpoint become.Footnote 34 The analysis of the Inner and the Outer Aspect of example (25 (= 19)) will serve as an example for these kinds of verbs.

(25) | 秦始皇既并天下 | ||||

Qín Shĭ | huáng | jì | bìng | tiānxià | |

Qin First Emperor already unify empire | |||||

‘After the First Emperor of Qin had unified the empire, … | |||||

(26) | The analysis of a default constellation with a [+perfective] Outer AspectP and a transitive [+telic] Inner AspectP with an accomplishment or an achievement verb |

The analysis of this example is representative for the accomplishment (or transitive achievement) verbs with a causative, agentive subject and a cause event as V1 discussed above: The theme moves up to [Spec, AspP] of the Inner AspP, in order to be measured out and the verb moves up to V1 checking its [+telic] features in the Inner Aspect phrase; the Inner AspectP is selected by the head of a [+perfective] Outer Aspect phrase with the perfective aspectual adverb in its specifier. This is one of the default constellations with the aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已.

The analysis of this example is representative for the accomplishment (or transitive achievement) verbs with a causative, agentive subject and a cause event as V1 discussed above: The theme moves up to [Spec, AspP] of the Inner AspP, in order to be measured out and the verb moves up to V1 checking its [+telic] features in the Inner Aspect phrase; the Inner AspectP is selected by the head of a [+perfective] Outer Aspect phrase with the perfective aspectual adverb in its specifier. This is one of the default constellations with the aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已.

-

(b)

Intransitive (unaccusative) achievement verbs

In the next group of examples the theme (internal) argument appears as the syntactic subject of the clause. This construction is frequently analyzed either as an unmarked passive or an ergative (unaccusative) construction in the linguistic literature on Late Archaic Chinese. It refers to a resultant state obtained after a change of state; it lacks the subevent cause and only consists of the subevent become (Travis 2010, p. 103f) and the telicity features of a dynamic event. The verbs in examples (27) to (29) lì 立 ‘enthrone/enthroned’, zàng 葬 ‘bury/buried’, and the prototypical achievement verb chéng 成 ‘complete’, are typical for this construction. All verbs are modified by jì 既. In example (29) jì 既 appears in a finite predicate marked by the sentence final particle yĭ 矣; this SFP typically co-occurs with the aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已. The exact function of the SFP is still under debate; it may constitute the head of the Outer AspectP as mentioned above, or, for instance, a functional category such as finiteness as one reviewer suggested. Although the SFP yǐ矣 frequently occurs in combination with one of the aspectual adverbs, it is certainly not mandatory in this position. Additionally, it occasionally seems to appear in adverbial (i.e., subordinate) temporal clauses; this might provide an argument against the finiteness hypothesis.Footnote 35 , Footnote 36

(27) | 燕噲既立, 齊人殺蘇秦. | Shǐjì: 34; 1555 | |||

Yān Kuài | jì | lì, | Qí rén shā Sū Qín | ||

Yan Kuai already enthrone, Qi man kill Su Qin | |||||

‘After Kuai of Yan had been enthroned, the men of Qi killed Su Qin.’ | |||||

(28) | 簡子既葬, 未除服, 北登夏屋, 請代王. | Shǐjì: 43; 1793 | ||||||||

Jiǎn | zĭ | jì | zàng, wèi | chú | fú, | bò | dēng | Xiàwū, | ||

Jian zi already bury, NEGasp remove mourning.clothes, north ascend Xiawu, | ||||||||||

qĭng | Dài wáng | |||||||||

invite Dai king | ||||||||||

‘After Jian zi was already buried, but one had not removed the mourning clothes yet, he (Jian zi) ascended mount Xiawu in the north and invited the king of Dai.’ | ||||||||||

(29) | 子之為智伯, 名既成矣. | Shǐjì: 86; 2521 | |||||

Zĭ | zhī | wèi Zhì bó, | míng jì | chéng | yĭ, | ||

You GEN for Zhi earl, name already complete SFP, | |||||||

‘Regarding [the way] you [acted] on behalf of earl Zhi, you already made yourself a name [for it] (lit: your name for it has been completed).’ | |||||||

The same kind of unaccusative verbs as in the examples discussed above can also be modified by the adverb yĭ 已. In example (30) the verb dìng 定 ‘establish, set up’ is again modified by yĭ 已 (as in ex. (22), the theme appears in subject position preceded by the temporal adverb jīn 今 which additionally marks the factual occurrence of the situation).

(30) | 今天下已定, 法令出一, 百姓當家則力農工, 士則學習法令辟禁. | Shǐjì: 6; 255 | ||||||||||

Jīn | tiānxià | yĭ | dìng, | fǎ | lìng | chū | yī, | bǎi | xìng dāng | |||

Now empire | already establish, law order go.out one, hundred clan deal.with | |||||||||||

jiā | zé | lì | nóng | gōng, | shì | zé | xué | xí | fǎ | lìng | ||

household then put.effort agriculture labor, noble then learn practice law order | ||||||||||||

bì jìn | ||||||||||||

prohibition | ||||||||||||

‘Now, the empire has been/is pacified and all the laws and orders are issued from one point; the common people, when they concern themselves with their households, have to put their efforts into agriculture and labor, and the nobles have to learn and practice the laws and orders and the prohibitions.’ | ||||||||||||

All predicates in this construction refer to resultant states whether marked by an aspectual adverb or not. This argues for an aspectual domain within an articulated VP (vP), in which the telicity features are checked, since in Late Archaic Chinese the verb never moved out of this domain (see Aldridge 2011). The aspectual adverb emphasizes the attainment of this resultant state and—at least in most instances—its relevance for the subsequent situations. Cinque (1999, p. 94) assumes that the contribution to the semantics of the predicate of adverbs of the type already (as specifiers of a functional head T(anterior)) appears minimal; in two subsequent sentences they force a temporal priority reading—a “precedence with respect to a reference time”—for the sentence in which they appear [quoting Hornstein (1997)].

The following group of examples represents genuine intransitive telic verbs with a theme subject, i.e., true achievement verbs in the sense of Travis (2010); most typical of this group are verbs of the word family zú 卒 ‘die, pass away’. Both the change-of-state point as in example (32), and the resultant state, as in example (31), can be emphasized by the adverb. In example (31) the resultant state is explicitly measured for its duration by a postverbal duration phrase. In example (32) the adverb qián 前 immediately precedes the verb; this position is the default position of manner adverbs and of directional adverbs such as běi 北 ‘northward’. In the immediate preverbal position qián 前 merely refers to the sequence of events, it does not function as a true point of time adverbial, because in the hierarchy of adverbs the latter do not appear in this low position.Footnote 37 The combination of the two aspecto-temporal adverbs yǐ 已 and jì 既 modifies a matrix (finite) predicate which is followed by the sentence final particle yĭ 矣.Footnote 38 , Footnote 39

(31) | 司馬相如既卒五歲, 天子始祭后土. | Shǐjì: 117; 3072 | |||||||||

Sīmǎ Xiāngrú jì | zú | wŭ | suì, | tiān | zĭ | shĭ | jì | Hòu | tŭ | ||

Sima Xiangru already pass-away five year, heaven son BEG sacrifice Venerable earth | |||||||||||

‘Sima Xiangru was already dead for five years when the Son of Heaven started to sacrifice to the Lord of the Earth.’ | |||||||||||

(32) | 伯邑考既已前卒矣. | Shǐjì: 35; 1563 | |||||

Bó Yìkǎo | jì | yĭ | qián | zú | yĭ | ||

Bo Yikǎo already already before die SFP | |||||||

‘Bo Yikao had already died before then.’ | |||||||

The following example represents a genuine intransitive motion verb, which supposedly is unaccusative; the subject is the theme whose motion is specified (Rappaport Hovav and Levin 1992, p. 251).Footnote 40 In Late Archaic Chinese and in Medieval Chinese these verbs do not necessarily require an open locative object or a directional complement to have a telic reading. In example (33) the motion verb chū 出 ‘go out’ is modified by yǐ 已 in a finite predicate including the SFP yǐ 矣.

(33) | 曰: 漢王已出矣. | Shǐjì: 7; 326 | ||

Yuē Hàn wáng yĭ | chū | yĭ | ||

Say Han king | already go.out | SFP | ||

‘He said: “The king of Han has already left [the city].”’ | ||||

The examples in this sub-section all represent true achievement verbs according to Travis’s (2010) definition, i.e., they are telic verbs with a theme subject. No cause or process subevent is involved in the structure of the predicate. The theme subject is always definite and measured out. As an example, the analysis of the Inner and the Outer Aspect phrase of example (34 (=30)) will be presented.

(34) | 今天下已定 | ||||

Jīn | tiān | xià | yĭ | ding, | |

Now heaven below already establish | |||||

‘Now, the empire has been/is pacified …’ | |||||

(35) | The analysis of a default constellation with a [+perfective] Outer AspectP and a [+telic] Inner AspectP with an intransitive (true) achievement verb |

The analysis of this example is representative of an unaccusative achievement with a definite and measured out theme subject: V1 represents an event (e represents the event variable) which can be labelled as the result of a become event; the telic verb has to move up to V1 checking its telicitiy features in the Inner Aspect Phrase; the Inner AspectP is by default telic in combination with a perfective Outer Aspect phrase. Both constellations, the one with transitive telic verbs (accomplishments and achievements), and that with intransitive telic verbs with a theme subject (true achievements) are default constellations with the aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已. As can be expected according to the presented hypothesis, [+telic] verbs, whether transitive or intransitive, are most typically modified by the aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已. The latter usually refer to resultant states; they seem to be more frequently marked by one of the aspectual adverbs than the former (see Meisterernst 2015a).

The analysis of this example is representative of an unaccusative achievement with a definite and measured out theme subject: V1 represents an event (e represents the event variable) which can be labelled as the result of a become event; the telic verb has to move up to V1 checking its telicitiy features in the Inner Aspect Phrase; the Inner AspectP is by default telic in combination with a perfective Outer Aspect phrase. Both constellations, the one with transitive telic verbs (accomplishments and achievements), and that with intransitive telic verbs with a theme subject (true achievements) are default constellations with the aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已. As can be expected according to the presented hypothesis, [+telic] verbs, whether transitive or intransitive, are most typically modified by the aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已. The latter usually refer to resultant states; they seem to be more frequently marked by one of the aspectual adverbs than the former (see Meisterernst 2015a).

2.2 The aspecto temporal adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已 with genuine atelic verbs and derived atelic predicates

Occasionally, the aspecto-temporal adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已 also modify genuine [−telic] verbs, in particular state verbs, and even activity verbs. The selection of state verbs can be explained by the fact that these adverbs do not merely emphasize the final point of an achievement, but equally the initial point of the state resultant from an achievement. Thus they can—in analogy to a resultant state—also emphasize the initial point of a genuine state; the state verb receives an inchoative reading and the situation type of the entire predicate is shifted from atelic to telic. Even if jì 既 and yǐ 已 seem to emphasize the state itself, the initial bound of the state is always implied.Footnote 41 The same situation type shift can be observed in Modern Mandarin when state verbs are combined with the perfective marker—le (Smith 1997, p. 265).Footnote 42

(36) | Wo | bing-le. |

I | sick-LE | |

‘I got sick.’ | ||

This function of—le in state verb constellations can be compared with that of the aspectual adverbs of Late Archaic Chinese. The state verbs attested with jì 既 and yǐ 已 are mainly verbs of posture, adjectives, and verbs of knowledge and perception. The adverbs are confined to verbs that allow a change-of-state reading in their semantic structure, i.e., to stage level predicates; individual level predicates cannot be modified by either of them.Footnote 43 In the infrequent instances of an activity verb modified by jì 既 and yǐ 已, the arbitrary final point of the activity is activated and the situation is viewed in its entirety from an external perspective. In addition to the verbs and predicates which are attested with both jì 既 and yǐ 已, yĭ 已 can modify noun phrase predicates; these are usually numeral DPs.

The following examples (37)–(39) represent the adverb jì 既 modifying a verb of posture, an adjective, and a verb of knowledge, respectively. Although in all examples, evidently, a stative situation is emphasized, the initial bound of the state is always implied in a constellation with the adverb jì 既. The verb of knowledge and perception zhī 知 ‘know’ in example (39) can have a telic reading ‘learn to know, realize’, and an atelic reading ‘know’Footnote 44; here the state of ‘knowing’ is emphasized, but the initial bounding of the state—the achievement of knowledge—is included in the aspecto-temporal structure of the predicate by the employment of the adverb jì 既.Footnote 45

(37) | 樂閒既在趙, 乃遺樂閒書曰 | Shǐjì: 80; 2435 | |||||||

Yuè | Jiān jì | zài | Zhào, nǎi | wèi | Yuè | Jiān shū | yuē | ||

Yue Jian already be.in Zhao, then send Yue Jian letter say | |||||||||

‘After Yue Jian was already in Zhao, he sent a letter to Yue Jian saying:…’ | |||||||||

(38) | 錢既多, 而令天下非三官錢不得行,… | Shǐjì: 30; 1435 | ||||||||||

Qián | jì | duō, | ér | líng | tiānxià | fēi | sān | guān | qián | |||

money already numerous, CON order heaven below unless three office money | ||||||||||||

bù | dé | xíng | ||||||||||

NEG can go | ||||||||||||

‘But the money had already become plentiful/was already plentiful and an order was issued to the empire that unless it was money from the three offices it was not allowed to be put in circulation,…’ | ||||||||||||

(39) | 五帝三代之事, 百家之說, 吾既知之, 眾口之辯. 吾皆摧之, 是惡能困我而奪我位乎? | Shǐjì: 79; 2419 | |||||||||||

Wŭ | dì | sān | dài | zhī | shì, | bǎi | jiā | zhī | shuō, | wú | jì | ||

Five hegemon three dynasty GEN affair, hundred house GEN doctrine, I | already | ||||||||||||

zhī | zhī, | zhòng kŏu | zhī | biàn, | wú jiē cuí | zhī, | shì | wū | néng | kùn | |||

know 3.OBJ, all | mouth SUB dispute, I | all break 3.OBJ, this how can | distress | ||||||||||

wŏ ér | duó wŏ wèi | hū | |||||||||||

I | CON steal I position SFP | ||||||||||||

‘The affairs of the Five hegemons and the Three dynasties, and the doctrines of the Hundred schools, I already know them [well], the arguments of many voices, I have completely refuted them, so how could someone distress me and steal my position?’ | |||||||||||||

Identically to jì 既, yǐ 已 is confined to the modification of change-of-state verbs, i.e., stage level predicates. In example (40) yǐ 已 appears in a finite predicate with the state verb (adjective) yuǎn 遠 ‘far away, remote’ terminated by the SFP yǐ 矣.Footnote 46 The employment of the SFP is not obligatory with state verbs; this can be seen in the examples (5) and (38). Yǐ 已 also modifies verbs of knowledge, perception, etc. In example (41) the initial point of the state is emphasized; the predicate is again terminated by the SFP yǐ 矣. The predicate can refer to a situation in the past with relevance for the present (perfect), i.e., the change-of-state point is located in the past, or to a situation in the present, i.e., the change-of-state point is located at speech time, respectively.Footnote 47

(40) | 方其割肉俎上之時, 其意固已遠矣. | Shǐjì: 56; 2062 | |||||||

Fāng qí gē | ròu | zhŭ | shàng zhī | shí, | qí yì | gù | yĭ | ||

At | its cut meat sacrificial.table above GEN time, his thought certainly already | ||||||||

yuǎn | yĭ | ||||||||

far.away SFP | |||||||||

‘At the time when he cut the meat on the sacrificial table, his thoughts were certainly already far away.’ | |||||||||

(41) | 趣使使下令曰: 寡人已知將軍能用兵矣. | Shǐjì: 65; 2161 | ||||||||||

Cù | shĭ | shì | xià | lìng | yuē guǎ | rén | yĭ | zhī | jiàngjūn | néng | ||

Rapid send envoy deliver order say lonely man already know general | be.able | |||||||||||

yòng bīng | yĭ | |||||||||||

make.use soldier SFP | ||||||||||||

‘Rapidly, he sent an envoy to deliver an order saying: “I have already learned/already know that you, general, are able to make use of the soldiers.”’ | ||||||||||||

The examples in this section all represent original state verbs according to Travis’s (2010) definition. State verbs usually are not agentive; no cause or process subevent is involved in the structure of the predicate. Example (42 (=38)) serves to represent a typical coercion effect on a state verb, an adjective modified by the aspectual adverb jì 既.

(42) | 錢既多 | Shǐjì: 30; 1435 | ||

Qián | jì | duō, | ||

money already numerous, | ||||

‘But the money had already become plentiful/was already plentiful…’ | ||||

(43) | The analysis of (42) as a typical shifted state predicate |

Structurally, state verbs are very similar to true achievements with an originally telic verb and a theme subject. V1 represents an event which can be labelled as a resulting become event; the initial point of the event is determined in V1; the state verb has to move up to V1 checking its telicitiy features in the Inner Aspect Phrase. Since the two adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已 are confined to a [+perfective] Outer AspectP which requires a [+telic] Inner AspectP, a [−telic] verb has to check its telicity features in the [+telic] Inner AspectP in this construction. This induces a coercion effect from a [−telic] to a [+telic] predicate to the effect that the predicate receives an inchoative reading.

Structurally, state verbs are very similar to true achievements with an originally telic verb and a theme subject. V1 represents an event which can be labelled as a resulting become event; the initial point of the event is determined in V1; the state verb has to move up to V1 checking its telicitiy features in the Inner Aspect Phrase. Since the two adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已 are confined to a [+perfective] Outer AspectP which requires a [+telic] Inner AspectP, a [−telic] verb has to check its telicity features in the [+telic] Inner AspectP in this construction. This induces a coercion effect from a [−telic] to a [+telic] predicate to the effect that the predicate receives an inchoative reading.

The examples (44) and (45) represent some of the infrequent cases of jì 既 and yǐ 已 modifying a genuine activity verb. Activities have an arbitrary final point, they can stop but they do not finish (Smith 1997, p. 23). An activity can change into a telic situation by adding a definite and quantified internal argument as in Vendler’s (1967) famous example ‘run’ (activity) versus ‘run a mile’ (accomplishment),Footnote 48 but this is not the case in the following intransitive examples. The verb zhàn 戰 ‘fight’ in example (44) predominantly occurs as an intransitive activity verb. The activity verb shí 食 ‘eat’ in (45) represents a typical incremental theme verb, i.e., a [+telic] accomplishment predicate, when combined with a definite and quantified noun phrase object. But in example (45) the mere employment of the adverb yĭ 已 shifts the situation type from atelic to telic. In both examples, the arbitrary endpoint of the situation is emphasized, and not the process part; in unmarked predicates the process part is the only visible part of the temporal structure of these verbs. The situation is viewed in its entirety from a perfective viewpoint.Footnote 49

(44) | 不如私許曹, 魏以誘之, 執宛春以怒楚, 既戰而後圖之. | Shǐjì: 39; 1665 | ||||||||

Bù | rú | sī | xŭ | Cáo, Wèi yĭ | yòu | zhī, | zhí | Yuān Chūn | ||

NEG be.like privately agree Cao, Wei in.order.to seduce 3.OBJ, seize Yuan Chun | ||||||||||

yĭ | nù | Chŭ, jì | zhàn ér | hòu tú | zhī | |||||

in.order.to annoy Chu, already fight CON after plan 3.OBJ | ||||||||||

‘Would it not be better to privately consent to Cao and Wei in order to seduce them and to seize Yuan Chun in order to annoy Chu; and after we have fought the battle we can consider this.’ | ||||||||||

(45) | 天子已食, 乃退而聽朝也. | Shǐjì: 83; 2463 | ||||||||

Tiān | zĭ | yĭ | shí, nǎi | tuì | ér | tīng | cháo | yĕ | ||

Heaven son already eat, then retire and listen court SFP | ||||||||||

‘When the son of heaven has finished his meal they retire and hold court.’ | ||||||||||

The coercion effect on [−telic] activity verbs is represented by example (45). The subject of the typical activity verb shí 食 ‘eat’ is evidently agentive; no final point is determined within the articulated VP, e.g., by a definite internal argument. A typical activity verb includes a cause or a do sub-event in V1.Footnote 50 The verb has to move up to V1 checking its telicitiy features in the Inner AspectP, which is required to be [+telic] due to the aspectual adverb yǐ 已. An intransitive activity verb with a cause or do sub-event in V1 does not provide any boundaries to the event, and without a definite internal argument providing an endpoint, the final point of the event can only be determined in the [+telic] Inner AspectP. The shift of the originally [−telic] situation type of the activity verb is induced by a [+perfective] Outer AspectP. In contrast to a state verb, for which the initial boundary is determined by the Inner AspectP, for an activity verb it is always the final boundary that establishes the endpoint.

(46) | The analysis of a typical shifted activity verb |

3 The adverbs of the imperfective aspect cháng 常 and sù 素

In this section a very short overview of two adverbs of the imperfective aspect will be provided. The adverbs presented here are cháng 常 and sù 素 which can both express the habitual and/or continuous aspect, the most typical subcategories of the imperfective aspect according to Comrie (1976, p. 25).Footnote 51 The imperfective aspect is typically compatible with atelic verbs; these are state and activity verbs. However, many verbs can shift from the telic to the atelic category and vice versa when modified accordingly, which also effects the aspectual representation.

The basic semantics of cháng and sù 素 are (see Meisterernst 2015a, b)Footnote 52:

-

(a)

cháng 常

-

1.

Cháng 常 can appear independently of any temporal restriction in past, present or future contexts marking habitual and habitually reoccurring situations.

-

2.

Cháng 常 has [+habitual], [+/−frequency], [+/−continuous] aspectual values. According to its imperfective aspectual features, the default feature of the Inner Aspect Phrase is [−telic]; [+telic] VPs are not excluded from the selection, but the telicity features of the predicate shift according to the imperfective feature of the Outer Aspect Phrase from telic to atelic.

-

1.

-

(b)

The adverb sù 素:

-

1.

The aspectual adverb sù 素marks habitual situations in the past; it characteristically refers to situations that start at some (unspecified) point in the past and continue up to speech time or some other reference time.

-

2.

Sù 素 has [+habitual], [+continuous], ([+/−frequency]) aspectual values,Footnote 53 indicating features typical for the imperfective aspect. According to the imperfective aspectual features of the Outer Aspect phrase, the [−telic] feature is the default feature of the Inner Aspect Phrase.

-

1.

Both adverbs belong to the closed class of aspecto-temporal adverbs confined to the preverbal position. Both cháng 常 and sù 素 by default combine with mono-phasal non-events [−telic]; if they combine with usually bi-phasal event verbs or predicates, the different phases of the event seem to be cancelled in the habitual predicate.

(47) | The structure of [−telic] situations following Abraham (2008) |

(47a) | activity | (| >>>>>>>>> |) or | |

t1 | E | tn | |

常/素 | |||

(47b) | state | | ~~~~~~~~~~ | | |

tm | E | tn | |

常/素 | |||

3.1 The adverb cháng 常

Although several meanings are assigned to cháng 常 in the linguistic literature, it seems best characterized as an adverb which expresses habituality independently of a temporal location of the situation (Meisterernst 2015a, b). It can also express frequency; frequency adverbials are typical for habitual sentences.Footnote 54 It modifies adjectives, state verbs other than adjectives, activity verbs and telic verbs. With state and with activity verbs it can refer to continuous habitual situations, but also to states or activities that re-occur under particular conditions. With telic verbs it refers to a habitually re-occurring situation, thus cancelling the [+telic] features of the verb and shifting the predicate from telic to atelic. When referring to habitual situations, predicates modified by cháng 常 are always semantically stative, i.e., atelic. According to its syntax and its impact on the telicity reading of the articulated VP, it evidently belongs to the category of aspectual adverbs, generated in an Outer Aspect Phrase with the imperfective features [+continuous] [+habitual]; these have the capacity to cancel the [+telic] features of the VP in the Inner Aspect Phrase. In example (48), the adverb cháng 常 explicitly marks the stative situation expressed by the state verb fá 乏 ‘lack’ with an indefinite internal argument and a theme subject as habitual. Occasionally cháng 常 is attested with typical [−telic] activity verbs with an agentive subject and a cause or do sub-event as in example (49) with the verbs xué 學 ‘study’ and shì 事 ‘serve’. Both are default constellations with the [−perfective adverb] cháng 常; no internal boundaries are provided anywhere within the articulated VP.Footnote 55

(48) | 漢使數百人為輩來, 而常乏食. | Shǐjì: 123; 3174 | |||||||||

Hàn shì | shù | bǎi | rén | wéi bèi | lái, | ér | cháng | fá | sì, | ||

Han envoy several hundred man be | group come, CON CHANG lack food, | ||||||||||

‘The Han envoys come in groups of only several hundred men, but constantly they lack food, …’ | |||||||||||

(49) | 故與李斯同邑而常學事焉, 乃徵為廷尉. | Shǐjì: 84; 2491 | ||||||||||

Gù | yŭ | Lĭ Sī tóng | yì | ér | cháng | xué | shì | yán, | nǎi | zhēng wéi | ||

Because with Li Si same city CON CHANG study serve there, then effect make | ||||||||||||

tíngwèi | ||||||||||||

commandant.of.justice | ||||||||||||

‘Since he came from the same city as Li Si and used to study and serve [with him] there, he appointed him thereupon to the post of commandant of justice.’ | ||||||||||||

An indefinite internal argument does not provide an endpoint for the situation; it does not measure out the event and thus does not move up to [Spec, IAspP].

(50) | The analysis of a default constellation with a [−perfective] Outer and a [−telic] Inner AspectP |

If cháng 常 modifies an originally telic predicate, the [+telic] feature of the predicate is cancelled due to the coercion effect of the [−perfective] Outer AspectP on the Inner AspectP, and the situation type of the predicate shifts from telic to atelic. Predicates expressing frequently occurring and habitual situations are stative (Smith 1997, p. 34).

If cháng 常 modifies an originally telic predicate, the [+telic] feature of the predicate is cancelled due to the coercion effect of the [−perfective] Outer AspectP on the Inner AspectP, and the situation type of the predicate shifts from telic to atelic. Predicates expressing frequently occurring and habitual situations are stative (Smith 1997, p. 34).

(51) | 曰: 每王且赦, 常封三錢之府. | Shǐjì: 41; 1754 | |||||||||

Yuē | mĕi | wáng qiĕ | shè, | cháng | fēng | sān | qián | zhī | fŭ | ||

Say | whenever king FUT grant.amnesty, CHANG close three money GEN treasury | ||||||||||

‘They said: “Whenever the king is going to grant an amnesty, he will always close the treasury of the three sorts of money.”’ | |||||||||||

Example (51) will be analyzed as representative for the coercion effect of a habitual, i.e., [−perfective] Outer AspectP hosting the imperfective aspectual adverb cháng 常on an originally [+telic] verb which is by default incompatible with the imperfective aspect. The subject (overtly appearing in the preceding clause) is causative and agentive; V1 is a cause event. Because the predicate has a habitual reading, the theme is, although definite, not measured out. It does not move up to [Spec, IAspP] and thus it does not provide a final boundary to the event. The usually [+telic] verb fēng 封 ‘close, seal up’ is required to check its telicity features in the [−telic] Inner AspectP corresponding to the [−perfective] feature of the Outer AspectP; accordingly the predicate shifts to [−telic].

(52) | The analysis of a shifted telic predicate in a constellation with cháng 常 |

3.2 The adverb sù 素

The adverb sù 素 ‘habitually from the past to the present’ explicitly marks a situation as habitual and continuous, beginning in the past and continuing up to speech time or some other reference time. Habitual sentences are stative and they denote a state that holds consistently over an interval of time (Smith 1997, p. 33f). Smith’s definition of the habitual fits well with the semantics of predicates modified by sù 素. Verbs modified by sù 素 are usually atelic, i.e., state verbs, such as verbs of perception or knowing, or adjectives, and activity verbs; sù 素 can also appear with a nominal predicate. Very occasionally, it is attested with originally telic verbs involving a shift of the situation type of the predicate. If sentences with sù 素 are terminated by a sentence final particle, this is usually yĕ 也, the sentence final particle related to stativity, imperfectivity and nominalization (see Pulleyblank 1995).

In example (53) sù 素 modifies the state verb ài 愛, an individual level predicate referring to an unchangeable state and, accordingly, to a permanent situation. These verbs are only compatible with adverbs expressing habituality and with adverbs of degree; they are not attested with the perfective adverbs jì 既 and yǐ 已. Occasionally sù 素also modifies an activity verb such as shì 事 ‘serve’ in example (54) (see also ex. (49) and the analysis in (50)), which refers to a habitual and continuous activity; the duration of the situation is explicitly marked by a durational complement.Footnote 56

(53) | 禦寇素愛厲公子完, 完懼禍及己, 乃奔齊. | Shǐjì: 36; 1578 | |||||||||

Yù Kòu sù | ài | Lì gōng zĭ | Wán, | Wán jù | huò | jí | jĭ, | nǎi | bēn Qí | ||

Yu Kou SU love Li duke son Wan, Wan fear misfortune reach self, then flee Qi. | |||||||||||

‘Yu Kou had always loved the son of duke Li, Wan, and Wan feared that misfortune might reach himself and thereupon he fled to Qi.’ | |||||||||||

(54) | 寡人素事南越三十餘年, | Shǐjì: 106; 2828 | |||||||

Guǎ | rén | sù | shì | Nán Yuè | sān | shí yú | nián, | ||

Lonely man SU serve Nan Yue three ten rest year, … | |||||||||

‘I have always served Nan Yue for more than thirty years, …’ | |||||||||

As a representative example for the default constellation with the [−perfective] adverb sù 素, example (53), expressing an unchangeable transitive state, will be discussed. The subject of the verb ài 愛’love’ is an experiencer or theme and not an agent. V1 represents a stative transitive situation have; the theme argument is definite, but not measured out; no event boundaries are present in the temporal structure of the predicate. A [−perfective] Outer AspectP requires a [−telic] Inner AspectP; the verb moves up to check its default telicity features in the Inner AspectP. In this default constellation no coercion effects are involved.

(55) | The analysis of a default constellation with a [−perfective] Outer AspectP and a [−telic] Inner AspectP |

4 Conclusion

In this paper the existence of an Inner Aspect Phrase within an articulated VP (vP) in Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese has been argued for. Following Travis (2010) it has been proposed that this AspP hosts the lexical aspect of the verb and corresponds to an Outer Aspect Phrase outside the VP, which hosts the grammatical aspect. This correspondence of the two Aspect Phrases accounts for the close connection between aspectual adverbs and the telicity features of the verb in Late Archaic and Early Medieval Chinese. However, the precise constraints of a systematic overt marking of the grammatical (imperfective—perfective) aspect and the lexical aspect (the telicity features) of the verb, by any syntactic or morphological means, still have to be established. This includes the constraints of an existing ancient system of a morphological aspectual marking by affixation. This morphological system probably concerns the lexical aspect, the Inner Aspect Phrase, rather than the grammatical aspect, the Outer Aspect Phrase. If this hypothesis proved to be correct, the grammatical aspect would not have been marked in the morphology of the verb at all, but purely by lexical means, i.e., by aspectual adverbs and, possibly, by sentence final particles. Accordingly, it has been proposed that the aspectual adverbs are generated in the specifier position of the Outer Aspect Phrase; the sentence final particles yǐ 矣 and yě 也might act as possible heads of the phrase. It has to be conceded, though, that neither of the positions has to be filled overtly; the head of the Outer AspectP can be zero and its specifier does not have to be filled either. Because of the boundaries inherent in its temporal structure, a perfective reading can be attained with any telic verb alone without any additional marking. Atelic verbs by default exclude the final points of the situation and accordingly express an imperfective viewpoint.

The particular semantics of a predicate marked by one of the perfective aspectual adverbs jì 既 and yĭ 已, and the imperfective aspectual adverbs cháng 常 and sù 素 may best be analyzed as adding focus or emphasis to a particular part of the temporal structure of the verb. This is the final or—with some verbs—the initial point for the perfective adverbs, and for the imperfective adverbs it is the process or stage part of the predicate. If they appear as specifiers of an Outer Aspect Phrase, this, by default, combines with an Inner Aspect Phrase of the corresponding aspectual feature: a [+perfective] Outer AspectP requires a [+telic] Inner AspectP, and a [−perfective] Outer AspectP requires a [−telic] Inner AspectP. If the aspectual features of the Outer and the Inner AspectP do not converge, a coercion effect is induced: e.g., a [+perfective] adverb modifying a [−telic] state verb induces an inchoative reading of the state verb, thus shifting the situation type from state to event. Contrastingly, a [−perfective] adverb has the capacity to shift the situation type of a predicate with a [+telic] verb in the Inner AspectP to a [−perfective/-telic] situation type, e.g., a habitual reading. Coercion effects seem to depend on the employment of an aspectual adverb (or an aspectual sentence final particle). These semantic features demonstrate the close relation between the employment of the aspectual adverbs and the telicity features of the VP (vP) and argue for the generation of these adverbs as specifiers of an Outer AspecP in which the grammatical aspectual features perfective and imperfective are hosted.

Notes

According to Peyraube’s (1996) periodization this includes Pre-Medieval and the early part of Early Medieval Chinese.

This example is a paraphrase of Zuŏzhuàn, Zhāo (S hísānjīng zhùshū : 2070 上). The temporal adverbial is identical to the one in Zuŏzhuàn which is not surprising since the structure of these temporal adverbials did not change since the Late Archaic period.

A sentence-initial point of time adverbial appears in topic position, preceding the subject.

However, the question remains whether a separate functional head has to be assumed for each of these adverbs, or whether there is one single AspectP in a fixed position with the features [−/+ perfective] to which the respective adverbs adjoin. Even if this is the case, different functional heads probably have to be assumed for the other adverbs including the aspectual negative marker wèi 未, and particularly for jiāng 將 and qiě 且, but also for cháng 嘗. According to their more temporal function, the latter should appear in a higher position than the purely aspectual adverbs, but this does not necessarily seem to be the case.

Smith (1997, p. 1) labels these two aspectual categories “viewpoint aspect” and “situation type”; viewpoint aspect refers to “grammaticized viewpoints such as the perfective and imperfective;” situation type refers to “temporal properties of situations, or situation types.” She notes that “Viewpoints and situation types convey information about the temporal aspects of situations such as beginning, end, change of state, and duration…”.

The perfective adverbs are e.g., incompatible with individual level predicates; their employment can actually serve as a test for the telicitiy features of a verb.

The term situation is more neutral, because it equally refers to telic situations (events in a narrower sense) and atelic situations (activities and states) than the term event which is sometimes employed indiscriminately for all kinds of situations in the linguistic literature.

See Travis (2010, p. 118) who notes, “Famously, external arguments do not enter into the computation. This is what an Inner Aspect structure predicts.”

The Middle Chinese reconstructions follow Pulleyblank (1991). The two variants of both verbs bài 敗 and zhé 折 are discussed in Jin (2006, p. 82f) under the label of volitional verbs (zìzhǔ dòngcí 自主動詞) and in the context of causation and transitivity. Jin assumes that the change from voiceless to voiced causes a loss of volition and of transitivity (2006, p. 84). This argues for a localisation of these affixes in the domain of an articulated VP on a par with Travis’s proposal.

The two readings of 見 are discussed in Jin (2006, p. 67f) under e.g., the label of agentivity (shīshì xìng 施事性); a voiced initial appears with a theme subject (shòu shì 受事), and a voiceless initial with an agentive subject (shī shì 施事). This analysis corresponds well to the change in the semantics of the other verbs presented in this group; however, the subject of the transitive variant of the verb jiàn 見 is probably better labelled as an experiencer than as an agent of the verb. According to Jin (2006, p.71) the distinctive syntactic characteristic connected with a voiced initial is the lack of a subject which functions as the actor (dòngzuò de zuòzhě 動作的作者) of the action expressed by the verb.

In Classical Tibetan, the only productive inflectional suffix is –s. This is most characteristically found distinguishing the past and imperative stems from the present and future; it evidently has aspectual functions.

Old Chinese includes Early and Late Archaic Chinese up to the Han period (206 BCE–220 CE).

Jin (2006, p. 511) reconstructs r-de versus/r-de-s.

Jin (2006, p. 332) reconstructs kon versus kon-s.

The adverb jì 既 is older in this function than the adverb yǐ 已; this fact is reflected in some of the occasional functional differences between the two adverbs in Han period Chinese.

The syntactic differences between the aspectual adverbs in Late Archaic and Medieval and in Modern Chinese may be due to the fact that the perfective adverbs of Late Archaic Chinese are more aspectual, i.e. that they have the capacity to shift the situation type of the verb, than the corresponding Modern Chinese adverb yǐjīng 已經 which lacks this capacity according to Wei (2015, ex. 3).

See Lyons (1977, p. 707) for this definition of events. Abraham’s main issue is the Aspect-Modality interface and the compatibility of the respective aspects with deontic and epistemic modality.

The semantic decomposition of event structure has a long history; Dowty (1979, cf. Travis 2010, p. 95) already decomposed events into a cause and a become sub-event; this approach has been refined e.g., by Parsons (1990, cf. idem). Parson distinguishes a culminated event e that introduces the Agent, another event e’ introducing the Theme which is caused by the event e, and a final state for verbs such as ‘close’.

The structure of (17b–c) is a modified version of the structure proposed in Abraham in order to fit the purpose of this study.

One argument for the adoption of Smith’s framework for Late Archaic and Han period Chinese, and the equal treatment of agentive and non-agentive achievements, is the fact that both allow post-verbal duration phrases referring to resultant state duration; the process part is not present in the temporal structure of both kinds of achievements (Meisterernst 2005, 2015a, b). The following example represents a true achievement verb with a post-verbal duration phrase referring to the duration of a resultant state.

Both verbs are connected by ér 而 which marks the subordinate relation between V1 (subordinate) and V2 (matrix).

But see Hornstein et al. (2005, p. 107) who notes that verbs such as ‘arrive’ are unaccusatives.

The same instance also appears in Hànshū: 25A; 1233.

Tenny (1994) argues for a unification of three “canonical types of accomplishment and achievement verbs: change of state verbs, incremental theme verbs, and verbs of motion-to-a-goal …” (Cf. Tenny and Pustejovsky 2000a, b, p. 14). Tenny and Pustejovsky (ibid) concede that there remains the question whether these verbs “are always causative in the same way”.

See Wang (2015) who demonstrates that predicates with motion verbs may differ in their telicitiy features according to the complement attached: the same motion verb can result in a [+telic] predicate with an internal argument, and in a [−telic] predicate with a prepositional phrase attached.

This instance is almost identically attested in Hànshū: 32; 1835.

This is still the case in the later Buddhist literature (see Meisterernst 2011).

In the Late Archaic Literature most of the functions of jì 既 are identical with those of yǐ 已 at the end of this period. Instances with jì 既 in the complement of wén 聞 are not particularly infrequent in the Late Archaic literature; with zhī 知, however, they are extremely uncommon.

A variant of this instance is attested in Zhànguó cè: 204B/106/24, the jì 既 clause is identical.

The verb shā 殺 does not seem to belong to this category, though. If it appears with a theme subject it is marked as passive, i.e. it is marked explicitly as a derived state.

The cause part of the event is hardly visible in the temporal structure of the predicate.