Abstract

Asian immigrant-origin youth (IOY) are a large and growing population within the United States (U.S.). Yet, despite the high prevalence of mental health concerns, limited research has examined sources of stress that may lead to mental health concerns among Asian IOY. Further, despite low levels of mental health service use, no studies have directly explored the perceptions of Asian IOY about barriers to mental health service use generally. Hence, using a qualitative approach, this study sought to examine the perceptions of Asian IOY regarding sources of stress that may contribute to mental health concerns and barriers to mental health service use. Thirty-three (n = 33; 58% female) Asian IOY were directly queried through in-depth focus groups. Data were analyzed using a grounded theory approach. Themes relating to sources of stress that lead to mental health concerns among Asian IOY included (a) pressure to succeed and (b) stressors related to ethnic minority and immigrant status. Themes relating to barriers to mental health service use among Asian IOY included (a) parental reactions, (b) concerns with mental health treatment, (c) stigma against mental health services, (d) mental health literacy, and (e) pragmatic or logistical reasons. Findings provide insight into tailoring appropriate outreach efforts to increase mental health service use among Asian IOY.

Highlights

-

We directly queried Asian IOY to examine sources of stress and barriers to mental health service use.

-

Parental pressure to succeed was the most frequently endorsed stressor.

-

Parents are important gatekeepers to Asian immigrant-origin youth’s access to mental health services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Within the United States (U.S.), Asian Americans (AA), individuals with historical ties to over 20 countries across East and Southeast Asia as well as the Indian subcontinent, are the fastest growing ethnic minority group (Pew Research Center 2017). Between 2000 and 2010, for instance, the AA population increased more than 40% (Hoeffel et al. 2012), with as many as 20 million individuals currently identifying as AA (Pew Research Center 2017). Asian immigrant-origin youth (IOY), which include both first-generation (i.e., foreign-born) and second-generation (i.e., born in the host country with at least one foreign-born parent) individuals under the age of 25, are projected to comprise one in every ten youth by the year 2060 (Asian American Federation 2014). Asian IOY are thus a large and growing population within the U.S.

Sources of Stress among Asian IOY

As a whole, Asian IOY are seen as being more educationally and socially successful than other ethnic minority groups (Lee 1996). This perception has given rise to the “model minority” myth, a racial stereotype which categorizes AA as universally high achieving and free from experiences of systematic racism (Lee 2009a). However, research has demonstrated that Asian IOY are at high risk for mental health problems. For instance, AA IOY have been found to have lower levels of self-esteem (Greene et al. 2006) and higher levels of social stress and depressive symptoms (Zhou et al. 2003) than their peers. Moreover, risk for suicide among Asian IOY is also high, with intentional self-harm or suicide being ranked as the number one cause of death for Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) adolescents between the ages of 15 to 19 years of age (Heron 2018). Additionally, female AAPI adolescents between the ages of 15 to 24 have been found to have higher rates of suicide as compared to Black and Hispanic females (Heron 2018).

The high prevalence of mental health concerns among Asian IOY has been attributed to numerous stressors (Wyatt et al. 2015). Existing quantitative studies on sources of stress contributing to mental health concerns among Asian IOY have pointed to the impact of experiences of discrimination (Benner and Kim 2009; Greene et al. 2006), acculturative stress (Juang et al. 2012), intergenerational family conflict (Crane et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2013), and peer conflict (Shin et al. 2011) on mental health outcomes among Asian immigrant adolescents. Fewer studies, however, have engaged in qualitative explorations of sources of stress that may lead to mental health concerns among Asian IOY. For instance, perceptions of mental health providers serving a high portion of Asian IOY have been directly queried, finding that stressors faced by Asian IOY with impact on their psychological wellbeing included poverty, acculturative stress, intergenerational family conflict, stigma, and discrimination (Li et al. 2016; Ling et al. 2014). Further, results of focus groups with Chinese immigrant parents of school-aged youth indicated that parents perceived their children to be impacted by stressors related to acculturation differences, intergenerational conflict, discrimination, and academic stress (Li and Li 2017). Despite the importance of directly eliciting the perceptions of youth themselves (Soleimanpour et al. 2008), fewer studies have queried Asian IOY’s perceptions of sources of stress that may lead to mental health concerns. For instance, in an early, primarily quantitative examination of the perspectives of first-generation Asian immigrant youth, youth ages 12 to 18 years were prompted with one open-ended written questionnaire about participants’ difficulties as immigrants (i.e. “Since coming to the United States, what types of difficulties have you experienced?”). Participants’ responses indicated that they experienced stressors related to communication, unfamiliarity with local customs, interpersonal relationships, and academic issues (Yeh and Inose 2002). Further, when querying eight Japanese immigrant adolescents aged 14 to 19 years about difficulties encountered while adjusting to life in the U.S., results revealed that challenges associated with language acquisition, maintaining friendships, and racial discrimination were the most prominent (Yeh et al. 2003a, 2003b). In an investigation of the cultural adjustment process of urban Chinese first-generation immigrant adolescents 16 to 20 years of age, results of focus groups with students, parents, teachers, counselors, and support personnel indicated that youth experienced stress due to dramatic changes in living and working conditions after immigration, limited English proficiency, changes in family structure and dynamics, racism and invisibility, and loss of social support (Yeh et al. 2008). In a qualitative study of Chinese immigrant-origin adolescents, results indicated that acculturative stress and academic pressure from parents were significant sources of stress (Li and Li 2015). Although a variety of methods were employed to obtain these findings (e.g., focus groups, individual interviews, “ecomaps”, and written questionnaires), participants were predominantly from higher socioeconomic status families, with approximately 44% of participants’ parents holding bachelor’s or master’s degrees and 24% holding doctoral degrees, thus potentially limiting generalizability of the findings. Finally, in a recent study of AA youth and parents, thematic analysis of essays written about challenges in communication found that participants endorsed acculturation differences, parental pressure to excel, and immigration-related challenges as relevant stressors (Wang et al. 2019b). Thus, despite providing useful insight to the experience of stress among Asian IOY, these studies were limited in their methodology (e.g., small sample size, use of written open-ended question) and focus (e.g., challenges related to cultural adjustment and immigrant status only, challenges faced within the family only, primary inclusion of Asian IOY from primarily high SES families).

Use of Mental Health Services among Asian IOY

Despite high levels of need, AA individuals have been found to be less likely to use mental health services (Abe-Kim et al. 2007). For instance, in a study of racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use among high risk youth, AAPI youth had the lowest rates of use (Garland et al. 2005). In a related study, 72% of at-risk AA youth aged 6 to 17, compared to 31% of their White peers, had unmet mental health needs (Yeh et al. 2003a, 2003b). Among AA adolescents with a diagnosis of depression, moreover, only 19% of received any treatment, a rate that was significantly lower than their White (40%), Black (32%) and Latino (31%) counterparts (Cummings and Druss 2011). AA adolescents have also been found to be less aware of mental health services offered at their school (Anyon et al. 2014; Arora and Algios 2019), a crucial system for the delivery of mental health services for youth. Such findings have underscored the need to better understand barriers to Asian IOY’s use of mental health services.

An abundance of quantitative research examining Asian IOY’s underutilization of mental health services exists (Bear et al. 2014; Guo et al. 2014). Findings from these studies have pointed to several barriers, including limited mental health literacy (Anyon et al. 2013) and increased shame and stigma about mental health problems (Eisenberg et al. 2009). Additionally, the role of family has been highlighted as a key factor contributing to underutilization of mental health service among AA adolescents, with AA adolescents having greater challenges in discussing mental health problems with their parents (Rhee et al. 2003).

Fewer studies have used a qualitative approach to explore barriers to mental health service use among Asian IOY. Among these, only the perceptions of social service providers (Ling et al. 2014), Asian immigrant parents (Wang et al. 2020), or young adults (Lee et al. 2009a, 2009b) have been examined. Results of these studies underscored the role of stigma toward mental health, low mental health literacy, fear of deportation, limited availability of culturally and linguistically appropriate services, and pragmatic barriers (i.e. lack of resources, time, money, language limitations) as barriers to mental health service access among AA adolescents (Ling et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2020) or young adults (Lee et al. 2009a, 2009b). Such findings are not surprising among recently immigrated individuals considering the restricted focus on mental health services and high levels of stigma toward such services among Asian countries (Meshvara 2002).

In a relevant study of Asian IOY, second-generation Chinese American youth were queried about their perception of school health programs. Results of focus groups revealed that second-generation Chinese American youth associated the use of school health programs for only high needs youth (e.g., those engaged in drug use) and had high stigma toward regular service users in their schools (Anyon et al. 2013). While this study did not directly query barriers to mental health service use generally, findings about views of such programming in schools provide insight as to reasons for underutilization of mental health services within the school setting.

Current Study

This study sought to examine two research questions: (1) What are the sources of stress that may contribute to mental health concerns among Asian IOY? and (2) What are Asian IOY’s perceptions of barriers to mental health service use? To build on past research, the current study incorporated the use of in-depth focus group methodology and directly queried Asian IOY’s perspective on these areas.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were adolescents (n = 33; 58% female) who self-identified as first- or second-generation Asian immigrants. Participants were between 14 to 20 years of age (M = 16.64, SD = 1.30) and attended one of three high schools that served a high number of IOY. Participants were predominantly Chinese (n = 25; 76%); other participants identified as Bangladeshi (n = 1), Burmese (n = 1), Indian (n = 1), Korean (n = 1), Malaysian (n = 1), Pakistani (n = 2), and Taiwanese (n = 1). English was not their first language for the majority of participants (n = 31; 94%), with Mandarin being the most commonly spoken language among participants (n = 25; 76%). Further, most of the participants were foreign-born (n = 27; 82%), while the remainder were the children of immigrant parents. Participants’ years in the U.S. ranged in number from 0 to 13 years (M = 3.43, SD = 3.17; see Table 1 for participant demographics).

Measures

Focus group questions

A semi-structured interview protocol was first created by the research team based on the needs expressed by school and community-based stakeholders (e.g., school principal, school social workers, community-based after-school educators) with whom the principal investigator had partnered. Stakeholders then reviewed and edited the protocol for content and language. All questions included additional prompts and alternative phrasing to assist the primary interviewer. For example, when participants were asked about whether Asian youth with mental health problems typically ask for help, the follow-up question for a “no” response was why they would not ask for help and what would happen if they did. Focus groups questions probed youth’s perceptions on (a) mental health needs in their community, (b) sources of stress that contribute to mental health problems in their community, (c) barriers to mental health service use, (d) potential enabling factors for help-seeking behavior, (e) perceptions of mental health services in school, and (f) recommendations for school mental health programming. Only content related to sources of stress that contributed to mental health concerns and barriers to mental health service use provided throughout the focus groups were included in this current study.

Demographic questionnaire

A demographic questionnaire was administered to participants in their preferred language (i.e., English, Mandarin, or Korean). The questionnaire included items querying participants’ age, gender, race and/or ethnicity, grade, primary language and other languages spoken, country of origin, and the number of years they and their parents/primary caregivers have lived in the U.S.. Participants immigration status was not queried.

Procedures

The current study was part of a larger community-based research partnership effort seeking to address the mental health needs of IOY. First, partnerships were established with schools and community-based organizations that served large numbers of Asian first- and second-generation IOY. The primary investigator and research team then met with stakeholders from these sites to elicit their needs as it related to supporting the mental health of their Asian immigrant-origin students. The development of the current study was based on the results of this needs assessment, which were largely related to barriers in engaging Asian IOY in school-based mental health services.

Potential participants were recruited by the primary investigator and research team members through visits to the partner sites. Meetings were held with eligible students (i.e., those who identified as first- or second-generation Asian immigrants) either during their lunch hour or during an afterschool program where members of the research team presented information about the study. Written documentation describing the study and parental consent forms were provided to students in the students’ preferred language (i.e., English, Mandarin, or Korean). Written materials were translated by native Mandarin or Korean speakers and back-translated to ensure meaning was maintained. Participants who obtained consent were included in the focus groups.

Focus groups (n = 7) were scheduled either during the school day or after school at the partner sites. In line with best practice recommendations, focus groups ranged in size from four to six participants and lasted between 40 to 70 min each (M = 53 min; Greenbaum 1988; Vaughn et al. 1996). Participants were grouped based on gender and grade level to facilitate sharing within the groups (Hoppe et al. 1995). Participants were not grouped by ethnicity given the overarching goal of identifying general perceptions of first- and second-generation immigrant Asian youth. Before the start of each focus group were began, each participant was asked to provide assent and complete the demographic survey.

Focus groups were led by an interviewer who was either the primary investigator or a member of the research team. The interviewer was assisted by a second research team member who took notes and prompted responses as necessary. All interviewers were trained by the principal investigator in delivering focus groups. In particular, interviewers were trained to ask questions based on the semi-structured interview protocol to ensure consistent rigor and objectivity in qualitative inquiry. However, interviewers were also allowed to follow-up with prompts and additional questions as needed for the purpose of maintaining rapport and clarifying information. Based on the language needs of the group, focus groups were held in either English or Mandarin. A third research member who spoke Mandarin or Korean was occasionally included in the English groups to provide translations when needed. At the beginning of each focus group, rules of confidentiality were discussed by the interviewer and participants were instructed to refrain from disclosing their families’ immigration status. All students were also informed that they were permitted to leave the group at any point during the session if they felt uncomfortable. Once focus group sessions were over, each participant was compensated for their participation with a $20 gift card.

All focus group sessions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by research team members. Sessions conducted in Mandarin were transcribed verbatim in Mandarin and then translated into English by two research team members who were bilingual in English and Mandarin (van Ness et al. 2010). To protect the identities of participants and maintain confidentiality, all transcripts were deidentified. All methods and materials used in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University and the New York City Department of Education.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed consistent with a grounded theory framework (Corbin and Strauss 2008; Strauss and Corbin 1997). A multistage coding process that involved three coders (i.e., doctoral level psychology students with school-based research and clinical experience) was used to code all data obtained from focus groups. In the first stage of analysis, the open coding phase, three out of the seven focus group transcripts were coded by all coders; this resulted in 373 initial codes. Similarities and differences among these initial codes were discussed among all three coders. Based on core concepts identified in the open coding, these initial codes were then grouped into 76 focus codes to help explain larger amounts of data in the next stage of coding, the axial coding stage. A codebook was created from the focus codes identified and each code was operationally defined. For example, the code “Causes of Mental Health Problems – Parent/Family Concerns” was operationally defined as: “When participants note that a cause of mental health problems is parent/family related.” The code “Barriers to Seeking or Accessing Mental Health Care – Stigma Against Counseling” was operationally defined as: “When participants say that stigma against counseling is a barrier to seeking or accessing mental health care.” Using two of the transcripts that were not included in the initial coding phase, the codebook was then tested by the three coders to see how well the codebook fit the data. This testing of the codebook also served the purpose of establishing interrater reliability among the three coders. During this stage, clarification of focus code definitions were made and additional focus codes were added before finalizing the codebook, resulting in a total of 83 focus codes. The seven transcripts (i.e., the three focus group transcripts used in the first stage along with the remaining four transcripts) were then divided among the three coders and coding was completed in NVivo using the finalized codebook. While coders completed coding independently, a team coding approach was used whereby coders periodically discussed the coding process and clarified any uncertainties about codes.

In the final stage of data analysis, the theoretical coding stage, focus codes were integrated into a guiding theory. Specifically, meetings were held to gain theoretical coding consensus among the three coders and create overarching themes from codes that fit together. As noted above, only content related to sources of stress that contributed to mental health concerns and barriers to mental health service use were included in this current study; in particular, 22 focus codes were used in the current study.

Results

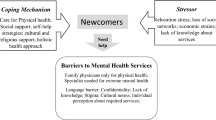

Multiple themes relating to the study’s research questions were identified from the participants’ responses. The first category of themes was related to sources of stress that lead to mental health concerns among Asian IOY. Two main themes were identified in this category: (a) pressure to succeed and (b) stressors related to ethnic minority and immigrant status. The second category of themes was related to barriers to mental health service use among Asian IOY. Five main themes were identified in this category: (a) parental reactions, (b) concerns with mental health treatment, (c) stigma against mental health services, (d) mental health literacy, and (e) pragmatic or logistical reasons. Themes are presented in descending order based on the frequency with which they were coded, representing an interaction between interviewer and participant(s). Frequency counts of endorsements by participants are not provided due to concerns about making inferences about the prevalence of these themes beyond the current sample (Neale et al. 2014). Relevant quotes from participants are also provided in text.

Sources of Stress

Pressure to succeed

When queried on the causes of mental health problems and experiences of stress among Asian IOY, most participants endorsed pressure to succeed academically and occupationally as a significant source of stress. Within this theme, two subthemes arose. The first subtheme related to parental pressure to succeed, while the second subtheme related to internalized pressure.

Parental pressure to succeed

Many participants endorsed parental expectations and pressures to succeed academically as one of the greatest sources of stress on Asian IOY’s mental health. Specifically, participants reported that Asian immigrant parents placed high expectations on them to perform well academically by obtaining good grades in school, engaging in extracurricular activities, and attending college. These high academic expectations, while serving as a route to better employment opportunities, also lead to mental health concerns among youth:

Student (S): A lot of Asian parents, they pressure their students, like, “Oh you have to go to this college, you have to do really well.” So like they get pressured and they get stressed out a lot because of school. And maybe they didn’t do so well in class where they expected to do well, and then they get, you know, depressed and sad.

In order to achieve these goals, many participants noted that they were often urged by their parents to engage in activities with which they had little interest. Some specified a lack of choice and feeling forced to meet these expectations without consideration for their personal preferences. For instance, one student mentioned that his parents did not consider his preference for colleges. Finally, when these expectations were not met, participants indicated that their parents either attributed their failure to a lack of effort or often compared them to others, explicitly expressing their disappointment:

S: They (parents) keep feeling that I am not a good child and always compare me to someone’s else daughter…. They will say, “Oh look at their child.” [They] give me all the pressure.

Internalized pressure

In addition to parental pressures, some participants also endorsed their own drive to succeed as a source of stress on Asian IOY’s mental health. Thus, while pressure from parents encompassed the majority of verbalizations, some participants also placed a high value on succeeding academically and recognized this pressure to succeed as “a standard that I set for myself, for the future [and] in terms of job prospects.” However, this internalizing pressure was often linked to pressure from parents. In particular, these participants reported that their internalized pressure stemmed from their parents’ high expectations for them. One student, explaining his desire to succeed, confounded the two sources of pressure:

S: We want to [go to a] good college, in order to be success[ful], get [a] job, so we have to be, you know, at the top. And [our parents] want you get higher score in the test, get higher score in the college…It has a lot of pressure.

Several participants noted that this pressure often resulted in them comparing their performance to others. For instance, one individual mentioned outshining others as an indicator of success and, relatedly, a source of stress on their mental health:

S: At times, I think others are doing better than I am. So I would like to surpass them.

Stressors related to ethnic minority and immigrant status

Concerns regarding their ethnic minority or immigrant status and experience was endorsed a source of stress among Asian IOY by many participants. Two subthemes were identified within this theme: discrimination related to ethnic and immigrant status and language.

Discrimination

Many participants endorsed experiencing discrimination as a function of their ethnic minority and immigrant status. Specifically, some reported verbal harassment from others related to being perceived as perpetual outsiders:

S: Cause people don’t really know who [we] really are. So they will [say], “Go back to your own country!” and, “You are taking up our space!”

Several others noted that experiences of bullying were common both in school and within their community. For instance, one student stated:

S: Many people who were born here, they bully. They say things to Asians like, “You’re from Asia not American! So why did you come here?” Like they’re teasing us like this. It’s kind of stressful.

Many participants also endorsed feeling compelled to fit into stereotypes about Asian IOY. In particular, they endorsed stress related to stereotypes about their academic potential as well as stereotypes of Asian IOY as being weak in sports.

Moreover, many participants also endorsed current anti-immigration sentiments as a source of stress on their mental health. Specifically, stress associated with their immigration status was endorsed, particularly as some did not see a route for obtaining legal status in the current political climate.

S: One president is trying to say that…he is going to make all immigrants go back to their own country… [We] are scared that is what will happen.

For others, the fear of deportation was an extreme source of stress that resulted in additional stress and feelings of hopelessness:

S: Let’s say if I am undocumented, I would be terrified [to be deported] cause I put all my work into academics. I did everything I could, like everything to survive over here. I learned a new language; I learned a new lifestyle and everything – everything in vain! I am trying to do my best to do in a college, but if that happens, everything is in vain.

Language

Some participants indicated poor English proficiency as a source of stress on Asian IOY’s mental health. For these participants, this challenge with language resulted in feelings of fear and isolation:

S: When I came to this country, I was a middle school student. I didn’t speak the language, and…I was scared of school. You know, because I was scared to talk because I didn’t speak English.

A few others indicated that their concerns with language had implications for their academic success in school by impacting their communication with teachers.

S: Yeah you can’t even explain why you didn’t do it (talk to the teacher).

Interviewer (I): Yeah. How did that feel? S: I cried at home alone. I tried but don’t know how to do and so [it was] stressful and I withdrew.

Finally, a small number of participants noted anxiety around being mocked for their language ability and additional stress at having to learn a language in addition to mastering the academic curriculum.

Barriers Against Mental Health Service Use

Parental reactions

In discussions about the barriers that prevent Asian IOY from seeking and obtaining mental health support, numerous participants endorsed parents as an important factor. Within this theme, two subthemes arose. The first subtheme related to parental permission to use mental health services, while the second subtheme related to parents’ responses to mental health need.

Parental permission

Many participants described obtaining parental permission as a barrier to seeking mental health services. When asked about whether their parents would grant them permission to seek mental health services, participants unanimously answered that their parents would not allow it. Some participants explained that this was due to the fact that parents equated the use of mental health services as a punishment and thus often discouraged mental health service use:

S: They see me as [an] average girl [and say] “I don’t know why you want to see a counselor; you have done nothing wrong.”

Moreover, several participants also noted that parents would be unwilling to provide permission to seek mental health support as they would be skeptical of their child’s true intentions. One student explained that their parents would view this request for help as a way for youth to lie to their parents:

S: They may think you’re hiding something from them, that you’re not willing to share with them.

Parents’ responses

In addition to parental permission, some participants noted that their parents believed that mental health services were meant only for severe problems. Specifically, participants noted that only externalizing problems are taken seriously by their parents and thus warranted seeking mental health support.

Additionally, some participants noted that their parents believed that their children should able to overcome mental health problems on their own without the use of mental health services. For instance, a few participants reported that Asian immigrant parents typically advised their children to ignore or forget about any problems experienced:

S: I think mental health is less obvious than physical health and parents would think that you would be best you would just figure it out.

Concerns with mental health treatment

Concerns regarding mental health treatment was also endorsed as a barrier to mental health service use among Asian IOY. Three subthemes were identified from this theme: discomfort opening up with others, confidentiality, and the perceived effectiveness of mental health treatment.

Discomfort opening up to others

Several participants endorsed feelings of discomfort related to disclosing their problems to others. Specifically, some attributed this discomfort to personality characteristics (e.g., shyness) and a lack of self-confidence to verbally express themselves to others in general:

S: If you’re shy, you don’t want to go out and talk about your things. And to relieve your pressure, you just stack up in your hearts. And maybe some outgoing people, they are like, telling their stories…and they get stress relief.

Some participants also indicated feeling uncomfortable disclosing their problems to mental health professionals due to their unfamiliarity with the provider, which would prevent the development of a trusting therapeutic relationship. In particular, a few described mental health professionals as “strangers.” Finally, participants also placed a high value in keeping personal problems a private matter, with one stating that Asian IOY “don’t want to talk about their personal things… it’s like a privacy.”

Confidentiality

A few participants also endorsed concerns regarding confidentiality of mental health treatment. In particular, participants endorsed a lack of trust that information they disclosed in treatment would remain confidential. These concerns surrounding breaches in confidentiality were amplified because of the associated negative consequences (e.g., parents finding out, academic consequences).

S: We will talk to them but the slightest discomfort, they will call your parents. Parents will get involve and [the] vice principle will get involve[d], and I don’t want that.

Perceived effectiveness

Some participants also noted concerns regarding the perceived effectiveness of mental health treatment. In particular, a few participants stated that mental health service providers would be unable to relate to their clients’ unique experiences and help solve their problems effectively:

S: I feel that [therapy] is not [helpful]. They normally don’t have the same experience as you [and do not know] what you need. They don’t know what situation you are [in]. Just feel that nobody can help. They just give you a hug maybe say something to make you feel better. The problem is not solved.

Stigma against mental health services

Several participants endorsed barriers related to stigma for mental health service use. These included perceived stigma by others and personal stigma.

Perceived stigma

Negative perceptions from others was endorsed as a barrier to mental health service use. Several participants mentioned that the fear of appearing undesirable to others deterred Asian IOY from seeking mental health treatment. The term “crazy” was commonly cited by participants as something many feared to be seen as by others in their community. Additionally, several participants indicated that concerns about seeking mental health treatment were also related to potential differential treatment by friends, family, and teachers if were to become aware of their utilization of mental health services. For instance, one student stated:

S: Like if my friends know this (that I seek treatment), are they going to treat me differently? Are they going to think I’m not a normal person who goes to therapy?

Personal stigma

Some participants also endorsed personal beliefs of stigma for those who used mental health services. Specifically, mental health service use was viewed by some participants as the inability of others to overcome problems on their own. For instance, in describing their perceptions about asking for help, one student mentioned, “Like your mind is too narrow. You cannot handle this independently.” Others likened mental health service use to a shameful act of admitting your wrongdoings:

S: Like you may have done something wrong and you want to share it with someone. What is something you did wrong? And why can’t you share that with your parents? Because that’s a really big deal, you did something really wrong, and that’s why you cannot share with your parents.

Mental health literacy

The two subthemes identified in this theme related to Asian IOY’s lack of knowledge on how to access mental health services and the lower priority placed on mental health.

Lack of knowledge

A few participants endorsed Asian IOY’s lack of knowledge on how to access mental health treatment as a barrier to mental health service use. For instance, one individual stated:

S: Well I also think they don’t ask because maybe they don’t know where to get for help, like maybe they don’t know who can they trust, who can they talk to, like they don’t know.

Importance of mental health

Some participants, moreover, also noted placing a reduced importance on mental health, with many individuals not taking mental health concerns seriously. For instance, one student noted

S: Everyone does not see this (mental health) as something important.

Pragmatic or logistical reasons

Lastly, a few participants reported pragmatic and logistical reasons as barriers to mental health service use. In particular, these participants stated that a greater emphasis was placed on other responsibilities and activities (e.g., work, family, peers) and with little remaining time to dedicate to mental health service use.

Discussion

With the goal of supporting the development of culturally informed intervention programming for Asian IOY, as well as reducing barriers to mental health service use, this study sought to elicit Asian IOY’s sources of stress that may contribute to mental health concerns among Asian IOY, as well as Asian IOY’s perceptions of barriers to mental health service use. Findings add to the growing literature on this understudied group and supports attempts to reduce disparities in mental health care engagement among Asian IOY.

Results indicated that Asian IOY experienced multiple unique sources of stress. In particular, findings from this study highlighted pressure to succeed academically as the most frequently reported stressor, particularly as it related to parental expectations for success. This finding is in line with past studies of Asian immigrant parents, as well as AA immigrant-origin young adults, and builds on the limited studies with Asian immigrant adolescents that have highlighted academic pressure to succeed by parents, and in particular balancing parental and youth expectations of success, as a major source of stress among Asian IOY (Lee et al. 2009b; Li and Li 2015; Li and Li 2017; Wang et al. 2019a, 2019b). Additionally, stressors related to ethnic minority and immigrant status, including discrimination and language-related stress, were also prevalent. Results of these study are in line with existing quantitative (Benner and Kim 2009; Greene et al. 2006) and qualitative studies (Yeh et al. 2003a, 2003b; Yeh et al. 2008) which have highlighted racial discrimination and language acquisition as major sources of stress among Asian IOY.

With regards to barriers to mental health service use, findings highlighted the unique role of parents in Asian IOY’s potential use of mental health service. Specifically, parental permission to use mental health services and parents’ misconceptions about the need for mental health were noted as significant barriers to mental health service use. The role of parents as gatekeepers to mental health services has been less frequently examined in research on barriers to mental health service use among Asian IOY. This may be because most qualitative research has queried the perceptions of social service providers (Ling et al. 2014), Asian immigrant parents (Wang et al. 2020), or young adults (Lee et al. 2009b) and not youth directly. As such, findings from this study expand our current understanding of barriers to mental health service use among Asian IOY by adding the unique perspective of the youth themselves. Findings from this study also underscored the role of stigma and limited mental health literacy as barriers to mental health service use; this finding is consistent with existing literature (Anyon et al. 2013, Eisenberg et al. 2009) underscoring the importance of these barriers to mental health service use among this population. Moreover, concerns with the treatment itself, particularly fears about breaches of confidentiality to parents, were noted as a barrier to mental health service use among Asian IOY. This finding adds to current understanding of barriers of mental health service use among Asian IOY, which has less frequently highlighted concerns with the therapeutic process itself among Asian IOY (Li and Seidman 2010). Study findings are also in line with existing research examining barriers to mental health service use among youth from other ethnic minority groups (Alegria et al. 2010).

Limitations

Various limitations of the current study should be noted. First, Asian IOY were examined as a whole rather than by ethnic group (e.g. Chinese, Indian, etc.). Given that within the Asian population itself, different ethnic minority groups tend to vary with regard to mental health service use (Anyon et al. 2013; Javier et al. 2014), potential areas for further research include examining the perspectives of Asian ethnic subgroups individually. Nonetheless, the majority of the group was first-generation Chinese IOY. As such, caution needs to be paid in generalizing findings to ethnic subgroups with less representation in the current sample. In addition, participants in this study were selected using convenience sampling from the same geographic, urban location. Hence, the results of this study may not be representative of the Asian IOY population across the U.S. Future research should attempt to conduct similar focus groups with Asian IOY from schools in other parts of the country. Further, although translators were present in focus groups conducted in English, students whose first language was not English may still have been hesitant to speak. Future research may benefit from conducting all focus groups in students’ native languages. Moreover, meaning can be lost while translating transcripts to English (van Nes et al. 2010). Despite efforts made to increase the validity and reliability of the data (e.g., have two bilingual research team members translate the data), it may be advantageous for future research to check interpretations by referring to the original data or using a professional translator (van Nes et al. 2010). Additionally, given that data from this study was audio-recorded rather than video-recorded, we were unable to differentiate between participants based on their voice alone and were thus unable to assign unique identifiers to participants. Future research should consider addressing this concern to aid in reporting more in-depth narratives.

Implications

Findings from this study have important implications in addressing the mental health needs of school-aged Asian IOY. First, results highlight the importance of addressing the unique stressors experienced by Asian IOY that may lead to mental health concerns. Specifically, prevention programming can be tailored to address the identified the stressors experienced by Asian IOY youth. For instance, prevention programming which seeks to build coping skills focused on addressing academic-related stress, and in particular builds healthy parent-child communication around this topic may be particularly beneficial (Hoagwood et al. 2007). In addition, as findings from this study revealed the potential disconnect between Asian IOY’s experiences of stress and Asian immigrant parents’ perceptions of these stressors, AA immigrant parents may be benefit from psychoeducation the supports needed by youth to foster positive mental health. Building upon unique sources of family strength and resilience among this understudied population (Wong et al. 2012), prevention programming should seek to engage parents in evidence-based workshops with culturally competent providers to encourage effective communication skills within a safe environment between Asian immigrant parents and their youth.

Additionally, Asian IOY’s reported experiences of stress related to ethnic minority and immigration status underscore the need to a promote safe and supportive school climate free from experiences of race-based discrimination and anti-immigration sentiments (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2010). As research has indicated that teacher support is a strong predictor of students’ sense of belonging in schools (Allen et al. 2018), it is crucial for teachers to receive training on how to create safe environments for Asian IOY students, as well as how to improve home-school collaborations by more effectively engaging Asian immigrant parents in a cultural sensitivity manner (Vazquez-Nuttall et al. 2006).

Findings also highlight the importance of addressing misconceptions and stigma surrounding mental health and mental health service use among both Asian IOY and Asian immigrant-origin parents. Mental health literacy interventions, which provide psychoeducation about mental health and mental health services with the goal of increasing knowledge, reducing stigma, and improving mental health help-seeking behaviors (Jorm et al. 1997), may be particularly relevant for this group. Existing evidence-based mental health literacy interventions for youth (Wei et al. 2013) may be a helpful starting point, though systematic investigations of programs with Asian IOY are still needed (Cheng et al. 2018). Relatedly, given that Asian IOY endorsed concerns regarding the confidentiality and effectiveness of counseling, mental health professionals should be transparent by relaying information about the counseling process. Further, as findings highlighted the key role of negative parental reactions to mental health service use among the most prominent barriers to Asian IOY utilization mental health services, these mental health literacy efforts should also be directed towards parents as a means of increasing Asian immigrant parent knowledge of mental health and potentially increasing mental health service use among their children. Such efforts may be integrated at parent-teacher conferences (Ouellette et al. 2004; Rao et al. 2019) or delivered via web to accommodate parents’ busy working schedules (Deitz et al. 2009).

References

Abe-Kim, J., Takeuchi, D. T., Hong, S., Zane, N., Sue, S., Spencer, M. S., Appel, H., Nicdao, E., & Alegría, M. (2007). Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and U.S.-born Asian Americans: results from the national Latino and Asian American study. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 91–98.

Alegria, M., Vallas, M., & Pumariega, A. (2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(4), 759–774.

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D. V., Hatie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: a meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34.

Anyon, Y., Ong, S. L., & Whitaker, K. (2014). School-based mental health prevention for Asian American adolescents: Risk behaviors, protective factors, and service use. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 5(2), 134–144.

Anyon, Y., Whitaker, K., Shields, J. P., & Franks, H. M. (2013). Help-seeking in the school context: Understanding Chinese American adolescents’ underutilization of school health services. Journal of School Health, 83(8), 562–572.

Arora, P. G., & Algios, A. (2019). School-based mental health for Asian American immigrant youth: Perceptions and recommendations. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 166–181.

Asian American Federation. (2014). The state of Asian American children. http://www.aafederation.org/doc/AAF_StateofAsianAmericanChildren.pdf

Bear, L., Finer, R., Guo, S., & Lau, A. S. (2014). Building the gateway to success: An appraisal of progress in reaching underserved families and reducing racial disparities in school-based mental health. Psychological Services, 11(4), 388–397.

Benner, A. D., & Kim, S. Y. (2009). Experiences of discrimination among Chinese American adolescents and the consequences for socioemotional and academic development. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1682–1694.

Cheng, H., Wang, C., McDermott, R. C., Kridel, M., & Rislin, J. L. (2018). Self-stigma, mental health literacy, and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(1), 64–74.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). ThousandOaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crane, D., Ngai, S. W., Larson, J. H., & Hafen, M. (2005). The influence of family functioning and parent-adolescent acculturation on North American Chinese adolescent outcomes. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 54(3), 400–410.

Cummings, J. R., & Druss, B. G. (2011). Racial/ethnic differences in mental health service use among adolescents with major depression. Journal of the American Academic of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(2), 160–170.

Deitz, D. K., Cook, R. F., Billings, D. W., & Hendrickson, A. (2009). A web-based mental health program: Reaching parents at work. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(5), 488–494.

Eisenberg, D., Downs, M. F., Golberstein, E., & Zivin, K. (2009). Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(5), 522–541.

Garland, A. F., Lau, A. S., Yeh, M., McCabe, K. M., Hough, R. L., & Landsverk, J. A. (2005). Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(7), 1336–1343.

Greenbaum, T. L. (1988). The practical handbook and guide to focus group research. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Greene, M. L., Way, N., & Pahl, K. (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 218–236.

Guo, S., Kataoka, S. H., Bear, L., & Lau, A. S. (2014). Differences in school-based referrals for mental health care: Understanding racial/ethnic disparities between Asian American and Latino youth. School Mental Health: A Multidisciplinary Research and Practice Journal, 6(1), 27–39.

Heron, M. (2018). Deaths: Leading causes for 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_06.pdf

Hoeffel, E. M., Rastogi, S., Kim, M. O., & Shahid, H. (2012). The Asian Population: 2010: 2010 Census Briefs. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf

Hoagwood, K. E., Serene Olin, S., Kerker, B. D., Kratochwill, T. R., Crowe, M., & Saka, N. (2007). Empirically based school interventions targeted at academic and mental health functioning. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 15(2), 66–92.

Hoppe, M. J., Wells, E. A., Morrison, D. M., Gillmore, M. R., & Wilsdon, A. (1995). Using focus groups to discuss sensitive topics with children. Evaluation Review, 19(1), 102–114.

Javier, J. R., Supan, J., Lansang, A., Beyer, W., Kubicek, K., & Palinkas, L. A. (2014). Preventing Filipino mental health disparities: perspectives from adolescents, caregivers, providers, and advocates. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 5(1), 316–324.

Juang, L., Syed, M., & Cookston, J. T. (2012). Acculturation-based and everyday parent adolescent conflict among Chinese American adolescents: Longitudinal trajectories and implications for mental health. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(6), 916–926.

Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., & Pollitt, P. (1997). “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. The Medical Journal of Australia, 166(4), 182–186.

Kim, S. Y., Chen, Q., Wang, Y., Shen, Y., & Orozco-Lapray, D. (2013). Longitudinal linkages among parent-child acculturation discrepancy, parenting, parent-child sense of alienation, and adolescent adjustment in Chinese immigrant families. Developmental Psychology, 49(5), 900–912.

Lee, S. J. (1996). Unraveling the “model minority” stereotype: Listening to Asian American youth. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Lee, S. J. (2009a). Unraveling the “model minority” stereotype: Listening to Asian American youth (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Lee, S., Juon, H., Martinez, G., Hsu, C. E., Robinson, E. S., Bawa, J., & Ma, G. X. (2009b). Model minority at risk: Expressed needs of mental health by Asian American young adults. Journal of Community Health, 34(2), 144–152.

Li, C., & Li, H. (2016). Longing for a balanced life: Voices of Chinese-American/immigrant adolescents from Boston, Massachusetts, USA. In B. K. Nastasi & A. P. Borja (Eds), International handbook of psychological well-being in children and adolescents: Bridging the gaps between theory, research, and practice (pp. 247–269). New York, NY: Springer Publishing.

Li, C., & Li, H. (2017). Chinese immigrant parent’s perspectives on psychological well-being, acculturative stress, and support: Implications for multicultural consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 27(1), 245–270.

Li, C., Li, H., & Niu, J. (2016). Intercultural stressors of Chinese immigrant students: Voices of Chinese-American mental health professionals. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 7(1), 64–73.

Li, H., & Seidman, L. (2010). Engaging Asian American youth and their families in quality mental health services. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 3(4), 169–172.

Ling, A., Okazaki, S., Tu, M.-C., & Kim, J. J. (2014). Challenges in meeting the mental health needs of urban Asian American adolescents: Service providers’ perspectives. Race and Social Problems, 6(1), 25–37.

Meshvara, D. (2002). Mental health and mental health care in Asia. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 1(2), 118–120.

Neale, J., Miller, P., & West, R. (2014). Editorial: reporting quantitative information in qualitative research: guidance for authors and reviewers. Addiction, 109(2), 175–176.

Ouellette, P. M., Briscoe, R., & Tyson, C. (2004). Parent-school and community partnerships in children’s mental health: Networking challenges, dilemmas, and solutions. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13(1), 295–308.

Pew Research Center. (2017). Key facts about Asian Americans, a diverse and growing population. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/08/key-facts-about-asian-americans/

Rao, A., Myszkowski, N., & Arora, P. G. (2019). The acceptability and perceived effectiveness of a psychoeducational program on positive parent-adolescent relationships for Asian immigrant parents. The School Psychologist, 73(1), 11–20.

Rhee, S., Chang, J., & Rhee, J. (2003). Acculturation, communication patterns, and self-esteem among Asian and Caucasian American adolescents. Adolescence, 38(152), 749–768.

Shin, J. Y., D’Antonio, E., Son, H., Kim, S. A., & Park, Y. (2011). Bullying and discrimination experiences among Korean-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 34(5), 873–883.

Soleimanpour, S., Brindis, C., Geierstanger, S., Kandawalla, S., & Kurlaender, T. (2008). Incorporating youth-led community participatory research into school health center programs and policies. Public Health Reports, 123(1), 709–716.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (Eds). (1997). Grounded theory in practice. Sage Publications, Inc.

Suárez-Orozco, C., Onaga, M., & De Lardemelle, C. (2010). Promoting academic engagement among immigrant adolescents through school-family-community Collaboration. Professional School Counseling, 14(1), 15–26.

van Nes, F., Abma, T., Jonsson, H., & Deeg, D. (2010). Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? European Journal of Ageing, 7(1), 313–316.

Vaughn, S., Schumm, J. S., & Sinagub, J. M. (1996). Focus group interviews in education and psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Vazquez-Nuttall, E., Li, C., & Kaplan, J. P. (2006). Home-school partnerships with culturally diverse families: Challenges and solutions for school personnel. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 22(2), 81–102.

Wei, Y., Hayden, J. A., Kutcher, S., Zygmunt, A., & McGrath, P. (2013). The effectiveness of school mental health literacy programs to address knowledge, attitudes and help seeking among youth. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 7(1), 109–121.

Wang, C., Do, K. A., Frese, K., & Zheng, L. (2019a). Asian immigrant parents’ perceptions of barriers preventing adolescents from seeking school-based health services. School Mental Health, 11(2), 364–377.

Wang, C., Marsico, K. F., & Do, K. A. (2020). Asian American parents’ beliefs about helpful strategies for addressing adolescent mental health concerns at home and school. School Mental Health: A Multidisciplinary Research and Practice Journal. Advance online publication.

Wang, C., Shao, X., Do, K. A., Lu, H., O’Neal, C., & Zhang, Y. (2019b). Using participatory culture-specific consultation with Asian American communities: Identifying challenges and solutions for Asian American immigrant families. Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation, 1-21.

Wong, A., Wong, Y. J., & Obeng, C. S. (2012). An untold story: A qualitative study of Asian American family strengths. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 3(4), 286–298.

Wyatt, L. C., Ung, T., Park, R., Kwon, S. C., & Trinh-Shevrin, C. (2015). Risk factors of suicide and depression among Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Youth: a systematic literature review. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 26(2 Suppl), 191–237.

Yeh, C. J., Arora, A. K., Inose, M., Okubo, Y., Li, R. H., & Greene, P. (2003a). The cultural adjustment and mental health of Japanese immigrant youth. Adolescence, 38(151), 481–500.

Yeh, C. J., Kim, A. B., Pituc, S. T., & Atkins, M. (2008). Poverty, loss, and resilience: The story of Chinese immigrant youth. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(1), 34–48.

Yeh, C., & Inose, M. (2002). Difficulties and coping strategies of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean immigrant students. Adolescence, 37(145), 169–182.

Yeh, M., McCabe, K., Hough, R. L., Dupuis, D., & Hazen, A. (2003b). Racial/ethnic differences in parental endorsement of barriers to mental health services for youth. Mental Health Services Research, 5(2), 65–77.

Zhou, Z., Peverly, S. T., Xin, T., Huang, A. S., & Wang, W. (2003). School adjustment of first generation Chinese-American adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 40(1), 71–84.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Pace University Institutional Review Board (IRB Code: 15-47) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arora, P.G., Khoo, O. Sources of Stress and Barriers to Mental Health Service Use Among Asian Immigrant-Origin Youth: A Qualitative Exploration. J Child Fam Stud 29, 2590–2601 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01765-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01765-7