Abstract

Objectives

Previous research has documented that perceived stress is negatively associated with adolescent life satisfaction. However, the mediating mechanisms underlying this relation are largely unknown. The present study tested whether self-control and rumination mediate the link between perceived stress and adolescents’ lower life satisfaction.

Methods

A sample of 1196 senior high school students (ages 13–19, 54% boys) completed questionnaires regarding demographics, perceived stress, self-control, rumination and life satisfaction.

Results

After controlling for gender, the results indicated that: (a) perceived stress was negatively associated with life satisfaction; (b) both self-control and rumination partially mediated the link between perceived stress and life satisfaction in a parallel pattern; and (c) self-control and rumination also sequentially mediated the relation between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

Conclusions

The current study advances our understanding of how perceived stress might lead to poor life satisfaction. Furthermore, the multiple mediation analysis reveals that self-control and rumination can not only in parallel, but also sequentially mediate the relation between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Life satisfaction has been a popular research theme in the social sciences. Life satisfaction is defined as a general assessment of one’s current feelings and attitudes about life, including satisfaction with the past and the future (Diener 1984). People with higher levels of life satisfaction feel that they have a better life than other people do (Erdogan et al. 2012). This is especially true for adolescents who are in an unstable developmental stage, when higher life satisfaction predicts lower levels of internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety, depression or attention problems) and less peer victimization in adolescents (Martin and Huebner 2007). In addition, life satisfaction can effectively buffer against the impact of undesirable factors on adolescents’ mental health (Tang and Chan 2017). Finally, enhancing adolescents’ life satisfaction has been considered the cornerstone of health promotion (Zullig et al. 2005) in this age group. Therefore, to provide practical suggestions for promoting health in this age group, it is essential to identify the underlying mediation mechanisms in the association between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

Perceived stress is a state reflecting the global evaluation of the significance of, and difficulty dealing with, personal and environmental challenges (Cohen et al. 1983). There is a positive relationship between stress and a wide range of negative outcomes (Bluth and Blanton 2014; Campbell-Grossman et al. 2016), and acute or chronic stressful situations generally put individuals at risk for psychological and physical problems (Dohrenwend 1998). Consistent with this viewpoint, a great many studies have found that perceived stress is strongly associated with negative emotions such as anxiety, anger and depression (Spada et al. 2008). These negative emotions are associated with lower life satisfaction (Suldo and Huebner 2004), as is perceived stress (Bluth and Blanton 2014).

Self-control refers to effortful control over the self by the self (Muraven and Baumeister 2000). When people attempt to change the ways that they would otherwise think, feel or behave, they are acting to increase self-control (Muraven, and Baumeister 2000). According to the strength model of self-control, stress undermines self-control (Muraven and Baumeister 2000). A body of research is consistent with this assumption (Boisvert et al. 2017; Cho et al. 2015; Converse et al. 2018; Duckworth et al. 2013). For example, childhood (grades 4 and 6) stress is related to poor self-control and appears to influence the ongoing development of self-control (Duckworth et al. 2013). Recently, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that perceived stress is negatively associated with self-control among both adolescents and young adults (Boisvert et al. 2017; Converse et al. 2018).

Self-control positively predicts adaptive behaviors (e.g., adaptive emotional responses) and negatively predicts problematic behaviors (e.g., alcohol abuse) in university students (Tangney et al. 2004). Research has also found that high levels of self-control predict job satisfaction, relationship satisfaction and parenting satisfaction (Converse et al. 2018). In addition, higher levels of self-control mean higher grade point average, higher self-esteem, more secure attachment, and better relationships with classmates and teachers, all of which enable adolescents to live happier and healthier lives (Tangney et al. 2004). From this perspective, previous studies have also shown that self-control can contribute to improved life satisfaction (Gao et al. 2016). Given that adjusting to stressful situations is thought to consume self-control resources and can lead to poor self-control (Muraven and Baumeister 2000), which in turn is associated with low life satisfaction, we assumed that self-control would act as a mediator in the relation between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

When people ruminate in the context of a dysphoric mood, they recall more negative memories from the past, interpret their current situation more negatively, and are more pessimistic about their future (Lyubomirsky et al. 1998). The response styles theory (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991) argues that rumination can lead to pessimistic thinking and interfere with instrumental behavior. Supporting this theory, there is evidence that rumination can prompt individuals to recall the unpleasant life events that they believe have caused their low levels of well-being (Song and Zhang 2016). Rumination may then lead to a negative appraisal of life. That is, the more rumination individuals engage in, the lower their life satisfaction. Studies on the direct link between rumination and life satisfaction have also demonstrated that rumination was a risk factor for low life satisfaction. For instance, some research has found that rumination can negatively predict life satisfaction even after controlling for subjective happiness and forgiveness (Eldeleklioğlu 2015; Ysseldyk et al. 2007).

Adolescence is a period of heightened stress (Katz and Greenberg 2015). The stress-reactive model of rumination emphasizes that stress generally increases rumination (Smith and Alloy 2009). Research has also found a significant positive correlation between perceived stress and rumination (Morrison and O’connor 2008), and stress could significantly induce and exacerbate rumination (Watkins 2008). Moreover, stress can influence individuals’ physical and mental health through the mediation effect of rumination (Valena and Szentagotái-Tatar 2015). For instance, Berset et al. (2011) demonstrated that the relationship between work stress and sleep quality was mediated via work-related rumination. Fan et al. (2016) revealed that rumination mediated the association between adolescents’ stressful peer interactions and depression. Considering that perceived stress is positively correlated with rumination, and rumination in turn is negatively correlated with life satisfaction, we assumed that rumination would be a significant mediator in the relation between adolescents’ perceived stress and lower life satisfaction.

Self-control has an important influence on rumination. Some researchers have argued that an individual with better self-control will feel a greater sense of control over the future (Baumeister et al. 2007). Self-control can effectively help ameliorate negative moods (Tangney et al. 2004), regulate negative emotion and inhibit unreasonable beliefs (Baumeister et al. 2007; Heatherton and Wagner 2011). Liu et al. (2018) demonstrated that self-control negatively predicted rumination. Thus, we proposed that self-control and rumination can sequentially mediate the link between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

In the present study, we tested the mediating mechanisms underlying the link between adolescents’ perceived stress and life satisfaction. Based on the literature reviewed above, we put forward three hypotheses: (a) self-control would mediate the relation between perceived stress and lower life satisfaction, (b) rumination would mediate the relation between perceived stress and lower life satisfaction, and (c) self-control and rumination would mediate not only in parallel but also sequentially the link between perceived stress and lower life satisfaction.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 1196 public senior high school students from 10th grade to 12th grade, identified through cluster random sampling. There were 562 girls and 634 boys, with a mean age of 16.75 years (SD = 0.94).

Procedure

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Psychological Research of the corresponding author’s institution. After informed consent was obtained from the schools, teachers, and the adolescents themselves, the students completed questionnaires regarding demographics, perceived stress, life satisfaction, rumination and self-control.

Measurements

Perceived stress

The Stress Subscale of the Chinese Short Version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-C21; Gong et al. 2010) was used to measure perceived stress. The Chinese version of the DASS-21 is a reliable and valid instrument and suitable for Chinese adolescents (Gong et al. 2010). The subscale is a 7-item self-report measure that assesses adolescents’ perceived stress. It uses a 4-point Likert type response format with values ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). An example item is “I found it difficult to relax”. In our study, Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.81.

Life satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985) was used to assess how satisfied an individual is with his or her life in terms of well-being. The Chinese version of the SWLS developed by Qiu and Zheng (2007). This self-report questionnaire measures perceived level of life satisfaction across five items using a 7-point Likert-type response format (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). An example item is “I’m satisfied with my life”. Results of the five items are summed to produce an overall score with high scores indicating high satisfaction with life. SWLS has been widely used in measuring Chinese adolescents’ life satisfaction, and has shown good reliability and validity (e.g., Chen et al. 2016; Luo et al. 2016). In our study, Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.78.

Self-control

The self-control questionnaire was developed by Chinese researchers (Dong and Lin 2011) to measure the ability to control and regulate impulsive behavior and impulsive expressions of emotion. This measure has been used in adolescent samples (Liu et al. 2018). The scale uses a 5-point Likert type response format with values ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An example item is “even though I’m angry, I don’t show it in my face”. A higher score means a higher level of adolescent self-control. In our study, Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.82.

Rumination

Adolescents’ rumination is often assessed with the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS, Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991). In this study, we used the 21-item Chinese version of the RRS developed by Yang et al. (2009). The Chinese version of RRS has been widely used in measuring Chinese adolescents’ rumination, and has shown good reliability and validity (e.g., Fan et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2018). Adolescents rate how true each item is for them, using a four-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The mean was taken, with higher scores representing higher levels of a ruminative response style. An example item is “I go away by myself and think about why I feel this way”. Cronbach’s a for the current sample was 0.92.

Data Analyses

To analyze the research data, we first used the software SPSS 23.0 to conduct descriptive statistics and correlational analyses. To test our hypothesized model, we conducted path analysis using SEM. We then conducted a Bootstrap analysis to test the multiple mediation model using Model 6 of the SPSS PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013). The PROCESS macro is available to test multiple mediating and moderating models with the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method, and it has been used extensively in psychological research (e.g., Jia et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2019).

Results

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics and correlations among variables. Overall, the correlations among variables were consistent with our expectations. Specifically, perceived stress was negatively associated with self-control and life satisfaction (r = −0.34, p< 0.01; r = −0.36, p< 0.01), but positively associated with rumination (r = 0.62, p < 0.01). Self-control was positively associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.37, p < 0.01) and negatively associated with rumination (r= −0.39, p < 0.01). In addition, rumination was negatively associated with life satisfaction (r = −0.48, p< 0.01). There were no significant age differences on any variable. However, there was a significant gender difference in self-control (F (1, 1194) = 5.15, p < 0.05), with girls showing higher self-control than boys. Therefore, gender was used as a control variable in subsequent analyses.

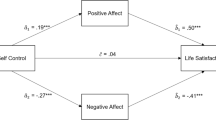

Because of the gender difference in self-control, we added a specific path from gender to self-control to make sure that the relationships among core variables could be better estimated (see Fig. 1). Results of fitness tests for the SEM path analysis were χ2/df = 0.420, RMSEA = 0.001, CFI = 0.999, NFI = 0.999, GFI = 0.999, which indicated an acceptable model fit.

As the results in Table 2 and Fig. 1 show, all the pathway coefficients were significant. After controlling for gender, perceived stress was negatively associated with self-control (b= −0.34, p < 0.001), and self-control in turn was positively related to life satisfaction (b = 0.20, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, high levels of perceived stress were positively associated with rumination (b = 0.55, p < 0.001), which in turn was negatively related to adolescent life satisfaction (b = −0.36, p < 0.001). Moreover, perceived stress was negatively related to life satisfaction (b = −0.07, p < 0.05), which suggested that the residual direct path way of “perceived stress → life satisfaction” was also significant. Thus, self-control and rumination only partially mediated the link between perceived stress and life satisfaction. The indirect effects were estimated using 5000 bootstrap samples. Results were deemed significant when the 95% CI did not include zero. Both the pathway representing “perceived stress →self-control →life satisfaction” (indirect effect = −0.07, 95% CI = −0.10 to −0.05), and the pathway representing “perceived stress →rumination →life satisfaction” (indirect effect = −0.20, 95% CI = −0.24 to −0.16) were significant. Moreover, the sequential pathway of “perceived stress →self-control →rumination →life satisfaction” was significant (indirect effect = −0.03, 95% CI = −0.04 to −0.02). Thus, self-control and rumination mediated the link between perceived stress and life satisfaction, not only in parallel but also sequentially.

Discussion

Perceived stress has been shown to have a significant association with adolescents’ life satisfaction. The results of our study extend the existing research by demonstrating that self-control and rumination, in parallel and sequentially, mediated this link. The current research contribute to document the role of how perceived stress is associated with adolescent life satisfaction.

Consistent with our hypothesis, our study found that self-control mediated the relationship between perceived stress and lower adolescent life satisfaction. This finding coincides with the self-control strength model, which posits that exposure to stressful and uncontrollable situations may deplete self-control resources, interrupt growth (e.g., relapse of negative habits), and further negatively influence individuals’ lives (e.g., poor life satisfaction) (Muraven and Baumeister 2000; Tangney et al. 2004). In addition, high levels of perceived stress are accompanied by negative moods, and people who want to bring themselves out of negative states will exert self-control (Muraven and Baumeister 2000). Moreover, in the context of high pressure, adolescents may use negative coping strategies (Xia and Ye 2014), such as smoking, drinking alcohol and overeating, and inhibiting these behaviors will deplete self-control. Adequate self-control resources are beneficial to ameliorate negative emotions and facilitate positive outcomes (Converse et al. 2018; Tangney et al. 2004); however, low self-control is associated with a series of undesirable effects. Based on related theory and existing research, we interpret our results as showing that perceived stress depletes self-control resources, and in turn relates to poor life satisfaction.

Congruent with our hypothesis, our results demonstrated that rumination was another significant mechanism through which perceived stress is linked to life satisfaction. This finding is consistent with previous research that showed that people who focused more on the present were less likely to be involved in rumination, which in turn triggered greater life satisfaction (Felsman et al. 2017). People with high perceived stress tend to feel threatened and challenged by stressors, and may think about negative events repeatedly (Song and Zhang 2016). They are inclined to recall negative events and memories and have difficulty in focusing on the present; that is, they engage in rumination. Based on the response styles theory, rumination thwarts effective problem-solving, triggers more negative emotion, and leads to lower levels of social support and higher levels of pessimism (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991). Rumination can produce a series of negative results, including less social support and more negative emotions, which further disrupt individuals’ lives and life satisfaction.

Finally, we found that self-control and rumination mediated the association between perceived stress and adolescent life satisfaction not only in parallel but also sequentially. Specifically, perceived stress was significantly linked to adolescent life satisfaction through both the unique effects of self-control and rumination, and their combined effect. Adolescents consume self-control resources when they try to control stressful events (Muraven and Baumeister 2000), and inadequate self-control resources can be connected with more rumination (Liu et al. 2018). This finding is in line with the self-control strength model that posits that stress consumes people’s limited self-control, and the decreased self-control resources may relate to negative performance (Cohen and Lichtenstein 1990). Specifically, low self-control can amplify negative emotions, which in turn trigger repetitive and passive thinking.

The impact of perceived stress on adolescent life satisfaction was sequentially mediated through self-control and rumination, although the magnitude of this association was relatively small. This result suggests that adolescents who experience high perceived stress have insufficient self-control resources, which drive them to engage in rumination (Liu et al. 2018), which in turn is associated with low life satisfaction. The finding that self-control and rumination are sequential mediators highlights the two major effects of high perceived stress—consuming and disrupting. Perceived stress consumes self-control resources and disrupts emotion regulation, thus ultimately exacerbating low life satisfaction. Meanwhile, self-control and rumination may show sequential relation; in other words, depleted self-control resources affect the emotional management process. It is necessary to note that although the sequential mediation effect of this study is basically equivalent to that of previous sequential mediation model (Jia et al. 2017) and has reached statistical significance, it is still weak, and the necessary caution should be maintained when interpreting the results.

By integrating the self-control strength model and the response styles theory, this study tested the mediating roles of self-control and rumination simultaneously. Our integrated multiple mediation model provides a more comprehensive conceptualization of how perceived stress is associated with adolescent life satisfaction. These two processes, namely self-control and rumination, jointly illuminate how perceived stress can play a role in adolescent life satisfaction.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, the study relied on self-report data, which may produce common method bias. Harman’s one factor test (Podsakoff and Organ 1986) was conducted on all measurement items to assess the possible common method bias. If the bias is substantial, either a single factor will emerge or one general factor will account for most of the variance (>40%). In the current study, the results revealed that the first factor did not account for the majority of the variance (28%) and there was no general factor in the unrotated factor structure. Moreover, we told participants that the questionnaire was anonymous, there were no right or wrong answers and they should answer the questions as honestly as possible (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Thus, we concluded that common method variance did not pose a serious threat in this study. Nevertheless, reports from multi-method and multi-informant methods (e.g., parents, teachers, and peers) should be considered in the future research. Second, as this study was conducted in adolescents, the findings may not generalize to other samples. Therefore, future research should recruit a more diverse sample of participants and further replicate the multiple mediation model in other samples. Third, this study used a cross-sectional research design, thus, causality cannot be determined. Future studies might address questions about causality with longitudinal or experimental designs. Fourth, given that self-control and rumination only partially mediated the relation between perceived stress and life satisfaction, it is warranted for future studies to examine the potential mediating effects of other variables, such as adolescents’ self-esteem. Finally, although beyond the scope of this study, it is possible that the direct link between perceived stress and life satisfaction is moderated by individual or environmental factors (e.g., social support). Future studies would benefit from further investigation of the moderating roles of these factors. Despite these limitations, this study makes a unique contribution by generating a theoretically-driven, relatively comprehensive model to clearly explain how perceived stress is associated with life satisfaction.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x.

Berset, M., Elfering, A., Lüthy, S., Lüthi, S., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). Work stressors and impaired sleep: rumination as a mediator. Stress and Health, 27(2), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1337.

Bluth, K., & Blanton, P. W. (2014). Mindfulness and self-compassion: exploring pathways to adolescent emotional well-being. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(7), 1298–1309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9830-2.

Boisvert, D., Wells, J., Armstrong, T. A., & Lewis, R. H. (2017). Serotonin and self-control: a genetically moderated stress sensitization effect. Journal of Criminal Justice, 56, 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2017.07.008.

Campbell-Grossman, C., Hudson, D. B., Kupzyk, K. A., Brown, S. E., Hanna, K. M., & Yates, B. C. (2016). Low-income, African American, adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and social support. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(7), 2306–2314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0386-9.

Chen, W., Niu, G. F., Zhang, D. J., Fan, C. Y., Tian, Y., & Zhou, Z. K. (2016). Socioeconomic status and life satisfaction in Chinese adolescents: analysis of self-esteem as a mediator and optimism as a moderator. Personality and Individual Differences, 95, 105–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.036.

Cho, I. Y., Kim, J. S., & Kim, J. O. (2015). Factors influencing adolescents’ self-control according to family structure. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(11), 3520–3530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1175-4.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404.

Cohen, S., & Lichtenstein, E. (1990). Perceived stress, quitting smoking, and smoking relapse. Health Psychology, 9(4), 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.9.4.466.

Converse, P. D., Beverage, M. S., Vaghef, K., & Moore, L. S. (2018). Self-control over time: implications for work, relationship, and well-being outcomes. Journal of Research in Personality, 73, 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2017.11.002.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Dohrenwend, B. P. (1998). Adversity, stress, and psychopathology. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

Dong, Q., & Lin, C. D. (2011). Introduction to standardized tests of psychological development of Chinese children and adolescents. Beijing: Science Press.

Duckworth, A. L., Kim, B., & Tsukayama, E. (2013). Life stress impairs self-control in early adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 3(3), 608–620. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00608.

Eldeleklioğlu, J. (2015). Predictive effects of subjective happiness, forgiveness, and rumination on life satisfaction. Social Behavior and Personality, 43(9), 1563–1574. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2015.43.9.1563.

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Truxillo, D. M., & Mansfield, L. R. (2012). Whistle while you work: a review of the life satisfaction literature. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1038–1083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311429379.

Fan, C., Chu, X., Wang, M., & Zhou, Z. (2016). Interpersonal stressors in the schoolyard and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: the mediating roles of rumination and co-rumination. School Psychology International, 37(6), 664–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316678447.

Felsman, P., Verduyn, P., Ayduk, O., & Kross, E. (2017). Being present: focusing on the present predicts improvements in life satisfaction but not happiness. Emotion, 17(7), 1047–1052. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000333.

Gao, F. Q., Ren, Y. Q., Xu, J., & Han, L. (2016). Shyness and life satisfaction: multiple mediating role of security and self-control. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24(3), 547–549. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2016.03.037.

Gong, X., Xie, X. Y., Xu, R., & Luo, Y. J. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(4), 443–446. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.04.020.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Heatherton, T. F., & Wagner, D. D. (2011). Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(3), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.005.

Jia, J., Li, D., Li, X., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., & Sun, W. (2017). Psychological security and deviant peer affiliation as mediators between teacher-student relationship and adolescent Internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.063.

Katz, D., & Greenberg, M. (2015). Adolescent stress reactivity and recovery: examining the relationship between state rumination and the stress response with a school-based group public speaking task. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 61, 23–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.452.

Liu, Q., Lin, Y., Zhou, Z., & Zhang, W. (2019). Perceived parent–adolescent communication and pathological Internet use among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01376-x.

Liu, Q. Q., Zhou, Z. K., Yang, X. J., Kong, F. C., Sun, X. J., & Fan, C. Y. (2018). Mindfulness and sleep quality in adolescents: Analysis of rumination as a mediator and self-control as a moderator. Personality and Individual Differences, 122, 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.031.

Luo, Y., Zhu, R., Ju, E., & You, X. (2016). Validation of the Chinese version of the Mind-Wandering Questionnaire (MWQ) and the mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between mind-wandering and life satisfaction for adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 92, 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.028.

Lyubomirsky, S., Caldwell, N. D., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1998). Effects of ruminative and distracting responses to depressed mood on retrieval of autobiographical memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.166.

Martin, K. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2007). Peer victimization and prosocial experiences and emotional well‐being of middle school students. Psychology in the Schools, 44(2), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20216.

Morrison, R., & O’connor, R. C. (2008). The role of rumination, attentional biases and stress in psychological distress. British Journal of Psychology, 99(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712607X216080.

Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408.

Qiu, L., & Zheng, X. (2007). Cross-cultural difference in life satisfaction judgments. Psychological Development and Education, 23(1), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-4918.2007.01.012.

Smith, J. M., & Alloy, L. B. (2009). A roadmap to rumination: a review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.003.

Song, Y., & Zhang, S. C. (2016). The effect of perceived social support on social anxiety: the mediating role of rumination and the moderating role of social undermining. Journal of Psychological Science, 39(1), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20160126.

Spada, M. M., Nikčević, A. V., Moneta, G. B., & Wells, A. (2008). Metacognition, perceived stress, and negative emotion. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(5), 1172–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.11.010.

Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2004). Does life satisfaction moderate the effects of stressful life events on psychopathological behavior during adolescence? School Psychology Quarterly, 19(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.19.2.93.33313.

Tang, K. N., & Chan, C. S. (2017). Life satisfaction and perceived stress among young offenders in a residential therapeutic community: latent change score analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 57, 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.03.005.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self‐control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x.

Valena, S. P., & Szentagotái-Tatar, A. (2015). The relationships between stress, negative affect, rumination and social anxiety. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies, 15(2), 179–189.

Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 163–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163.

Xia, F., & Ye, B. J. (2014). The effect of stressful life events on adolescents’ tobacco and alcohol use: the chain mediating effect of basic psychological needs and coping style. Journal of Psychological Science., 37(6), 1385–1391. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2014.06.017.

Yang, J., Ling, Y., Xiao, J., & Yao, S. Q. (2009). The Chinese version of the ruminative responses scale in high school students: Its reliability and validity. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 27–28. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2009.01.021.

Ysseldyk, R., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2007). Rumination: bridging a gap between forgivingness, vengefulness, and psychological health. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(8), 1573–1584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.032.

Zullig, K. J., Valois, R. F., Huebner, E. S., & Drane, J. W. (2005). Associations among family structure, demographics, and adolescent perceived life satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-005-5047-3.

Author Contributions

Y.Z. designed and executed the study, and wrote the paper. Z.Z. collaborated with the design and writing of the study. Q.L. analyzed the data and collaborated with the writing of the study. X.Y. collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript. C.F. collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Central China Normal University had provided IRB approval for the study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Y., Zhou, Z., Liu, Q. et al. Perceived Stress and Life Satisfaction: A Multiple Mediation Model of Self-control and Rumination. J Child Fam Stud 28, 3091–3097 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01486-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01486-6