Abstract

Objective

The current study explored longitudinal family conflict predictors of adolescent depressive symptoms occurring during middle childhood.

Methods

We tested the mediating effects of mother–child and father–child conflict when children were in 6th grade on the relation between interparental conflict when children were in 5th grade and adolescent depressive symptoms when children were in 9th grade in a sample of 601 families enrolled in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development.

Results

Fathers’ reports of interparental conflict at 5th grade were related to greater mother–child and father–child conflict at 6th grade, and mothers’ reports of interparental conflict at 5th grade were related to greater mother–child conflict at 6th grade. Further, greater mother–child conflict at 6th grade was related to greater adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade.

Conclusion

Results highlight the importance of understanding family system processes that unfold over time in predicting adolescent depressive symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Adolescence is a peak time period where the manifestation of depressive symptoms is most likely to occur (Auerbach et al. 2014). Depressive symptoms encompass a range of symptoms including depressed or irritable mood, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, psychomotor agitation, fatigue or lack of energy, decreased concentration or indecisiveness, insomnia or hypersomnia, significant weight loss or decrease in appetite, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Adolescent depression compromises academic achievement (Frojd et al. 2008), relates to greater risky behaviors (Hallfors et al. 2005), and may lead to suicide (Curtin et al. 2016). Previous literature has suggested family conflict contributes to emotional development in childhood and the severity of adolescent depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with a family systems perspective, demonstrating that conflict within certain family relationships can result in greater conflict in other relationships and in the family as a whole. Marital conflict can induce negative ripples across the family context (Margolin et al. 1996; Mikulincer et al. 2002). There is substantial reason to believe that the primary impact of parents’ marital relationship on adolescent well-being is indirect through the parent–child relationship (Jekielek 1998; Shek 1998). For children, marital conflict may place them in the precarious position of identifying which parent is an ally at the risk of being rejected by the other parent (Peterson and Zill 1986). For parents, marital strife may emotionally drain them and thus reduce parental sensitivity and attentiveness toward children (Easterbrooks and Emde 1988). Using a family systems theory framework, we identify how relational disruptions between specific family members extend to other family relationships during a key developmental period for children. To date, most research examining these family conflict and depression links has focused on early childhood (e.g., Trentacosta et al. 2008) or concurrent adolescent reports of marital and parent–child conflict (e.g., Harold and Conger 1997; Sands and Dixon 1986; Shek 1998). More prospective research is needed to understand the effects of interparental and parent–child conflict exposure in middle childhood on adolescent depressive symptoms.

Interparental conflict during middle childhood has been largely neglected as an independent predictor of parent–child conflict and mental health outcomes in adolescence. More specifically, parent–child conflict has been examined as a mediator linking marital conflict to adolescent behavior problems and depression (Bradford et al. 2008), but has yet to be tested longitudinally. Testing these associations over time is critical for establishing temporal precendence in the direction of effects. This is an important area for exploration given the developmental events that distinguish middle childhood from early childhood, making it a time period specifically relevant to changes in family dynamics and child well-being. School-age children are navigating how to effectively respond to environmental demands and internally regulate their emotions (Collins and Russell 1991; Paikoff and Brooks-Gunn 1991; Raffaelli et al. 2005), while simultaneously becoming more self-sufficient, less reliant on their caregivers, and more aware of their relationships (Kerns et al. 2001; Kerns et al. 2000). This places school-age children who witness marital conflict in a prime position for turbulent interactions with caregivers that may be eventually internalized as they reach adolescence. In addition, the mother–child relationship has received significantly more attention than the father–child relationship (Cooksey and Fondell 1996), although father involvement with children is uniquely important for their development (Lamb 2004). As fathers are becoming increasingly more involved with their children, it is critical to investigate how mother–child and father–child conflict differentially mediate associations between marital conflict exposure and adolescent depressive symptoms.

Conflict can include minor differences of opinion to major, recurring, and unresolvable disagreements. Regardless of the reasons for conflict, conflict between parents affects children’s development (Grych 2005; Grych et al. 2000). Indeed, children identified interparental conflict as a stressor compromising functioning in their daily lives (El-Sheikh et al. 2001), and this appears to extend into adolescence. Specifically, Cummings and Davies (2002) showed that mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of marital conflict were related to their children’s cognitive, emotional, social, and physiological responses to stress and predictive of adolescent functioning. Children in middle childhood and adolescence may be more negatively impacted by interparental conflict than younger children because they are more aware of the presence of conflict (Krishnakumar and Buehler 2000) and because their language skills enable them to more clearly communicate negative feelings and anger associated with the conflict (Cummings et al. 1994).

Mothers and fathers tend to vary in the ways they respond to their children’s emotions following interparental conflict. Mothers tended to be more responsive and provide more emotional reassurance to children during periods of heightened interparental conflict compared to fathers (Cox et al. 2001). Mothers also displayed more warmth in response to child distress than fathers (Davidov and Grusec 2006), a characteristic children seek out in stressful situations, such as when witnessing marital conflict. Mothers who are more supportive of their distressed children, despite high levels of marital conflict, were less likely to report that their children had long-term psychological health problems (Repetti et al. 2002). Fathers tend to provide emotional support to their children in other ways, like encouraging play and independence (Grossmann et al. 2002), but may find it more challenging to support children’s negative emotions, especially in times of heightened family stress. In stressful situations, fathers were more likely to withdraw emotionally from their children (Hetherington 1992). Children may interpret this withdrawal as a dismissal or abandonment, resulting in greater emotional insecurity (Lewis and Lamb 2003), and perhaps, increasing the risk of depressive symptoms over time.

Though a review of this research suggests that the father–child relationship may be most predictive of later adolescent depressive symptoms, marital conflict also has been shown to interfer with mothers’ sensitive responding to their children (Buehler et al. 2006). Mothers’ emotional resources necessary for sensitive caregiving can be absorbed by preoccupation with negative marital interactions (Owen and Cox 1997). Therefore, testing parent gender differences is warranted as we explore whether mother–child and father–child conflict uniquely contribute to the development of adolescent depressive symptoms due to differential styles of providing emotional support to children exposed to interparental conflict.

Interparental conflict can also compromise parent–child relationship quality (Gonzales et al. 2000; Margolin et al. 1996), with high amounts of interparental conflict increasing negativity and conflict between parents and children (Amato 1986; Erel and Burman 1995; Steinberg and Silk 2002). Consistent with family systems theory, parents’ emotions experienced in one context can affect the emotional quality of other family relationships (Margolin et al. 2004). Thus, it is plausible that one parent’s perception of interparental conflict can relate to his/her own reports of conflict with the child, as well as conflict between the partner and child. These spillover and crossover mechanisms may occur for a number of reasons.

The transfer of negative affect between family subsystems can occur through children’s mimicking of parental conflict behaviors, decreased emotional security, parents’ stress and reactivity, and family emotion socialization practices. Children’s imitation of parental conflict behaviors has been shown to influence their emotional regulation strategies (White et al. 2000). Feldman et al. (2004) findings suggest that after children observed an argument between their parents, they mimicked parents’ own emotional expressions, coping strategies, and resolution tactics in later arguments. If parents are not managing their own conflicts well, this mimicking of conflict behavior can negatively shape the way children understand, manage, and display emotions (Baker et al. 2011). Second, parents’ emotional unavailability can leave children feeling less secure in that relationship, a feature of the parent–child relationship that is particularly important during middle childhood (Ainsworth 2006). Emotionally insecure children tend to experience difficulties regulating their emotions (Davies and Cummings 1998), and have more difficulty coping with stressful events (Katz and Gottman 1996). Third, marital conflict also increases parents’ stress and reactivity (Sturge-Apple et al. 2009) and diminishes parents’ ability to model healthy emotion regulation for their children (Eisenberg and Morris 2002). And finally, spillover from the marital relationship into the parent–child relationship may operate through parents’ responses to children’s negative emotions, such as the distress children experience from marital conflict. Given that early adolescence is already marked by increases in parent–child contention (Montemayor 1983), caregivers’ diminished capacities to sensitively respond to children’s negative emtions and manage conflict with their children likely exacerbates the effects of conflict on later depressive symptoms.

parent–child conflict is a common occurrence within families. However, high parent–child conflict over the course of middle childhood can compromise children’s psychological health. Specifically, parent–child conflict has been associated with youth psychological distress, suicidal ideation, and depression (Connor and Rueter 2006; Harold et al. 1997; Steinberg 2001). parent–child conflict during early and middle childhood led to depressive symptoms later in middle childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood (Branje et al. 2010; Cole et al. 2002; Sheeber et al. 1997).

parent–child conflict predicted adolescent maladjustment in both concurrent (Cummings et al. 2005) and longitudinal studies (Eisenberg et al. 2001; Morris et al. 2002; Tucker et al. 2003). In one concurrent study of school-aged children, researchers found a positive association between marital conflict and adolescent depression, with significant indirect effects through parent–child conflict (Bradford et al. 2008). However, research has yet to investigate this process longitudinally from middle childhood to adolescence to truly test mediation accounting for previous levels of conflict and depressive symptoms, or to test differential effects of mother–child and father–child conflict on the development of later depressive symptoms in adolescence. Most research findings are focused on mother–child relationships, as mothers are typically children’s primary caregivers. While it is true that mothers tend to be more frequently involved in conflict exchanges with their children than fathers (Montemayor and Hanson 1985; Richardson et al. 1984), the father’s role as a parent is more complementary to mothers during middle childhood and adolescence than during earlier developmental periods (e.g., teaching practical skills; Block 1978). Further, the amount of time fathers spend with their children in on the rise (Yeung et al. 2001), and there is evidence that fathers significantly shaped the cognitive development and social competence of their children even after adjusting for maternal involvement (Amato and Rivera 1999; Yogman et al. 1995).

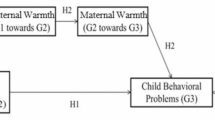

We examined the mediating effects of mother–child and father–child conflict at 6th grade on the association between mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade and adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade using data from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD). Our study furthers the field by examining the impact interparental and parent–child conflict during late middle childhood has on adolescents’ depressive symptoms; thus, the 5th, 6th, and 9th grade assessment waves were selected to evaluate our research questions. Furthermore, all study variables were available at each of these assessment waves, providing statistical advantages as we tested longitudinal mediation. As seen in the conceptual model in Fig. 1, we aimed to test whether there were direct effects from mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict to adolescent depressive symptoms. We hypothesized mothers’ and fathers’ greater perceptions of interparental conflict were related to more adolescent depressive symptoms. Additionally, we test relations between mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict and mother–child and father–child conflict, examining both spillover within parents (e.g., mothers’ reports of interparental conflict to mother–child conflict) and crossover between parents (e.g., mothers’ reports of interparental conflict to father–child conflict). We hypothesized mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of greater interparental conflict would relate to their own reports of greater conflict with their child, and to their partners’ reports of greater conflict with the child. Further, we tested the association between parent–child conflict and adolescent depressive symptoms. We hypothesized more parent–child conflict, particularly father–child conflict, would relate to larger increases in adolescent depressive symptoms. Finally, we tested the significance of indirect pathways from mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict to adolescent depressive symptoms through mother–child and father–child conflict to assess mediation. We hypothesized an indirect effect would emerge where mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of greater interparental conflict would relate to increases in adolescents’ depressive symptoms, in part, because of increased mother–child and father–child conflict.

Method

Participants

The sample used for the current study study is a subsample of participants enrolled in the NICHD SECCYD. This prospective longitudinal study was conducted at 10 research sites across the US beginning in 1991. All women who recently gave birth within these research sites were recruited for eligibility and further screening postpartum. Families were excluded from the overall study if the mother was younger than 18 years of age, lived more than an hour from the laboratory site, did not speak English, planned to move, acknowledged substance abuse, had an infant with a known disability, or had a multiple birth. A sample of 1364 families participated in a home interview when infants were one month old and were invited to continue with 15 measurement waves from early childhood through adolescence. There are additional study details about recruitment and selection available on the study website, https://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/supported/seccyd/Pages/overview.aspx.

The current subsample included 601 families who completed mother and father reports of interparental conflict at the fifth-grade assessment. Although fathers were not required to participate in later assessments for the family to be included in the subsample, if fathers did report at a later wave, they were required to be biologically related to children. This was done to ensure that the same father-figure provided data over time, as the SECCYD does not track whether a father-figure is the same or different as who reported at the previous assessment, and it was important in this longitudinal study to be sure that over-time reports were provided by the same person. In addition, parents could not be separated between the 5th and 6th grade time point. In sum, eligibility criteria excluded families with non-biological parents, single parents, and parents who separated between the first two time points (5th and 6th grade). The current study subsample was 51% female children, 83% Caucasian, 4% African American, 8% Hispanic, and 5% other ethnicities. According to income-to-needs ratios that measure poverty thresholds, 13% of families were considered low income (ratios two times the poverty threshold or less), 48% middle-income (ratios two to five times the poverty threshold), and 39% high-income (ratios five times the poverty threshold or greater). Ninety-six percent of mothers were married; 4% of mothers were unmarried and living with the child’s biological father. Compared to the full SECCYD sample, children in the current study subsample were more likely to be Caucasian, χ²(4) = 48.19, p < .001, and families had higher incomes t(910) = 7.671, p < .001.

Procedure

Study families began participating during the child’s first month of life, at which time they reported on demographic information at a home visit. Child gender was documented in an initial phone call or first home visit at one month. Although there were assessments throughout infancy and early childhood, for the purposes of this study, we focused on data collected in middle childhood and adolescence. When the study child was in 5th, 6th, and 9th grade, parents reported on their relationship with their partner and how they handled conflicts, as well as their relationship with their child and demographic information. Additionally, in 5th, 6th, and 9th grade, children reported on their depressive symptoms during a laboratory visit.

Measures

Adolescent depressive symptoms

Youth completed the Child Depression Inventory Short Form (CDI-S; Kovacs 1992) to assess depressive symptoms at the 5th and 6th grade (included in study model as covariates) and at 9th grade (dependent measure). The 10-item sum score was reliable for the 5th and 6th grade time points at α= .73, and for the 9th grade time point at α= .81. Adolescents rated the extent of symptoms by selecting statements that best described the way they felt over the last two weeks. An example of a statement from the CDI is, “I am tired all the time”. Scores ranged from 0 to 20 with higher scores indicating more symptoms. The CDI has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure (Messer 1995).

Interparental conflict

Parents completed the frequency of conflict subscale from the 20-item Partner Conflict and Resolution Measure (Braiker and Kelley 1979) at the 5th, 6th, and 9th grade. The 5th grade score was used as the independent variable in the current study; 6th grade and 9th grade assessments were included as covariates. Items were rated on a scale of 1 (Not at all) to 9 (Very much). The conflict subscale score was computed by taking the mean of items 1–5. The subscale was reliable for mothers, α= .84, and fathers, α= .81, at the 5th grade time point; for mothers, α= .84, and fathers, α= .83, at the 6th grade time point; and for mothers, α= .85, and fathers, α= .82, at the 9th grade time point. A sample question included, “How often do you and your partner argue with one another?” Higher scores indicated more conflict with the partner. This measure has been shown to have strong reliability and validity (Kerig 1996; Rands et al. 1981).

Parent–child conflict

Mothers and fathers reported on their relationship with their child using the Child-Parent Relationship Scale Short Form (Pianta 1992) at the 5th, 6th, and 9th grade. The 6th grade score was used as the mediating variable in the current study; the 5th and 9th grade scores were covaried. The conflict subscale included 15 items rated on a 1 (Definitely does not apply) to 5 (Definitely does apply) scale (e.g., My child and I always seem to struggle with each other). Higher scores indicated more conflict between parents and children. The subscale was reliable for mothers, α= .84, and fathers, α= .82, at the 5th grade time point; for mothers, α= .84, and fathers, α= .82, at the 6th grade time point; and for mothers, α= .87, and fathers, α= .86, at the 9th grade time point.

Covariates

Mothers reported on child gender when children were 1 month old, their marital status at the 5th grade wave, and family income at the 9th grade wave, which were included in the model as controls. We also controlled for separation or divorce between parents at 6th and 9th grade. We controlled for interparental conflict at 6th and 9th grade, parent–child conflict at 5th and 9th grade, and child depressive symptoms at 5th and 6th grade. This allowed us to examine the unique effect of variables at specific time points, test changes over time in the study variables by accounting for previous levels, and assess the longitudinal mediation of parent–child conflict.

Data Analysis

Initial analyses examined the frequencies and descriptive data for the variables in the current study. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test a path model in Mplus v.8 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2018). We used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation to account for missing data which ranged from 0 to 13% for study variables. In addition to controlling for interparental conflict at 6th and 9th grade, parent–child conflict at 5th and 9th grade, and child depressive symptoms at 5th and 6th grade, we also controlled for marital status at 5th grade, child gender, separation/divorce between the 6th and 9th grade waves, and family income-to-needs ratio at 9th grade. The covariates were entered in relation to all study variables.

Results

Table 1 displays study variable means, standard deviations, and ranges, and Table 2 shows correlations among constructs at all time points. Correlations among the study variables are fairly consistent with the hypothesized model. Notably, mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade were related to adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade; however, mothers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade were unrelated to fathers’ reports of parent–child conflict at 6th grade. Preliminary analyses also explored child gender mean differences among study variables. There was only one significant gender differences; 9th grade girls reported higher depressive symptoms (M = 2.36, SD = 2.95) than boys (M = 1.35, SD = 2.12); t (508) = −4.74, p < .001. Thus, child gender was include as a covariate in the study model.

We evaluated model fit using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the comparative fit index (CFI), as well as the significance of paths corresponding to study hypotheses. Acceptable model fit indices include RMSEA values smaller than .08, and CFI values within the range of .95–1.0 (Bentler 1990; Browne and Cudeck 1993, Hu and Bentler 1999). Because the chi-square statistic is dependent on sample size (Kline 2005), we did not rely on this criterion when determining adequate model fit.

The path model in Fig. 2 showed acceptable fit, χ2(7) = 45.85, p< .001, RMSEA = .08, 90% CI [.06, .11], CFI = .99. First, we hypothesized mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade would be directly related to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade. This hypothesis was not supported. There were no significant direct effects for parents’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade on adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade. Next, we hypothesized mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade would relate to increases in parent–child conflict at 6th grade. The hypothesis was partially supported. Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of greater interparental conflict at 5th grade related to increases in mother–child conflict at 6th grade. Additionally, fathers’ perceptions of greater interparental conflict at 5th grade related to increases in father–child conflict at 6th grade. Additionally, we hypothesized greater parent–child conflict at 6th grade would relate to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade. The hypothesis was partially supported. Greater mother–child conflict at 6th grade was associated with increases in adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade, but father–child conflict was not related to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms.

Model for interparental conflict and parent–child conflict predicting adolescent depressive symptoms. Marital status at 5th grade, separation or divorce between 6th and 9th grade, child gender, and family income-to-needs ratio are included as demographic controls. Interparental conflict at 6th and 9th grade, mother–child and father–child conflict at 5th and 9th grade, and 5th and 6th grade child depressive symptoms are also covaried. The standardized coefficients are presented in the model. Grayed paths are nonsignificant

Finally, we hypothesized there would be significant indirect effects from mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade to adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade through mother–child and father–child conflict at 6th grade. Again, the hypothesis was partially supported. Tests of indirect effects evaluated the significance of possible mediation pathways in the model. Mothers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade were related to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade through mother–child conflict at 6th grade, β = .02, p = .014, 95% CI [.01, .03], indicating that the more mothers perceived conflict with their partners, the more conflict they also perceived with their children one year later, which was, in turn, related to increases in adolescents’ reports of their depressive symptoms. Additionally, fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade were related to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade through mother–child conflict at 6th grade, β = .01, p = .047, 95% CI [.002, .024], indicating greater father perceptions of interparental conflict were also related to more mother–child conflict one year later, which was, in turn, related to increases in adolescents’ reports of their depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The current study evaluated the mediating effects of mother–child and father–child conflict on the association between interparental conflict and adolescent depressive symptoms over time. Examining adolescent depressive symptoms is particularly important because of the growing rate of adolescents experiencing at least one major depressive episode per year (NSDUH 2013). Adolescents experiencing depressive symptoms are at increased risk for problems with sleeping, eating, anxiety, substance use, and suicide (Birmaher et al. 1996). Exploring conflict interactions within the family in late middle childhood can shed light on processes that exacerbate adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Moreover, we focus on a developmental period marked by maturational shifts that are directly associated with the transition to adolescence (Collins and Russell 1991). Prior work has successfully attended to this connection between middle childhood and adolescence by noting how shifts in the parent–child relationship between these two time periods were driven by similar underlying developmental events (e.g., sensitivity to parental conflict; Cummings et al. 2003; Zimet and Jacob 2001). Given exposure to family conflict in middle childhood sets the course for parent–child relationship dynamics in adolescence, it is important to examine how the temporal unfolding of this process relates to adolescent mental health.

Interparental and Parent–Child Conflict

Consistent with family systems theory emphasizing the interdependence in family relationships, we found evidence of both spillover and crossover in family conflict. For spillover, mothers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade were associated with greater mother–child conflict at 6th grade, and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade were associated with greater father–child conflict at 6th grade. For crossover, fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade were associated with greater mother–child conflict at 6th grade. Irrespective of gender, interparental conflict can be threatening to children, resulting in negative emotional reactions, difficulties forming constructive coping strategies, and a heightened state of arousal and hyper-responsiveness. For example, Loeber and Hay (1997) argued that children of high conflict homes are unable to form constructive coping strategies to handle their own stressful conflicts; those children exhibited heightened emotional responses and engaged in more physical and verbal aggression toward their parents. Additionally, parents who frequently fought with their partners were more likely to respond negatively to their children, which increased the likelihood of evoking a negative response from children over time (Valiente et al. 2004). More specifically, there is some evidence to suggest that ongoing marital conflict gradually impaired mental health functioning (Fincham 2003). Parents with compromised mental and emotional resources may display diminished capacity to parent their children in sensitive and responsive ways.

We hypothesized that mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict during 5th grade would predict increased conflict with their children in the 6th grade. In partial support of this hypothesis, mothers’ perceptions of greater interparental conflict at 5th grade only related to their own parent–child interactions at 6th grade, but fathers’ perceptions of greater interparental conflict at 5th grade related to increases in both father–child and mother–child conflict over one year. This nuanced gender-specific crossover effect is a unique contribution of the current study. It suggests that mothers’ relationships with their children are multiply determined, both by their own and their spouse’s marital experiences. Marital disruption for father may uniquely impact the mother–child relationship in a number of ways. First, fathers tended to be aware of the role mothers play as an emotional peacekeeper (Meth et al. 1990). For this reason, they may rely on mothers’ emotional management in their marital relationship and with their child. Additionally, fathers have been shown to benefit from spousal support and cooperation to a greater degree than mothers, which related to their degree of involvement with children (Parke and Tinsley 1987). Subsequently, mothers may discover greater strain in their relationship with their child because fathers have lost their primary source of support and thus are less able to foster positive relationships with their children that may offset mother–child tension.

Parent–Child Conflict and Depressive Symptoms

The impact parent–child conflict can have on adolescent psychological well-being is well documented in the field (Shek 1998; Steinberg 2001), but studies examining both mother–child and father–child conflict in relation to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms over time are less common (Tucker et al. 2003). We hypothesized that greater parent–child conflict would relate to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms. Our hypothesis was partially supported. Although 6th grade father–child conflict was related to 9th grade adolescent depressive symptoms at a bivariate level, we found that when both mother–child and father–child conflict were included in the same model, only mother–child conflict related to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms. Again, accounting for both mother–child and father–child conflict in the same model provided valuable information about parent gender differences in family processes in relation to adolescent depressive symptoms. In past work, children who felt their emotional security was compromised due to mother–child conflict were more likely to report difficulties in self-acceptance and emotion regulation (Thompson 1994), and over time, these negative self-representations in middle childhood appeared to lead to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms (Brenning et al. 2012). One potential explanation for these parent gender differences is that children tend to look to their mothers as a source of support and emotional security (Lamb 1997). For this reason, a lack of maternal warmth was one concomitant of greater mother–child conflict (Bates et al. 1985). Children who experienced an inadequate amount of maternal warmth, paired with a high level of conflict with their mothers, had fewer resources to address their emotional needs (Scanlon and Epkins 2015). Because mothers tend to be responsible for emotions in the home (Erickson 2005), it is possible that children do not seek out the same emotional support from fathers that mothers usually provide.

Parent–Child Conflict as a Mediator

Finally, we hypothesized there would be a significant indirect association between parents’ perceptions of interparental conflict to adolescent depressive symptoms through increased parent–child conflict. Again, this hypothesis was partially supported. Although initial bivariate associations provided support for the direct effect of greater interparental conflict relating to more adolescent depressive symptoms, when testing the full model, direct associations between mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of interparental conflict at 5th grade and adolescent depressive symptoms at 9th grade were no longer significant. These bivariate relations seem to be explained by the proposed indirect pathways. First, mothers’ perceptions of interparental conflict were related to increases in mother–child conflict, which were, in turn, related to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms. As discussed earlier, mothers play an integral role in providing caregiving that supports school-age children’s emotional needs. Interparental conflict may compromise mothers’ abilities to provide this support and thus give rise to problems in the mother–child relationship. Youth in middle childhood who describe their families as higher in conflict report more depressive symptoms (Asarnow 1992). Our findings suggest that changes in the frequency of mother–child conflict is an important link between interparental conflict and changes in youth depressive symptoms.

Additionally, fathers’ perceptions of greater interparental conflict also predicted increases in mother–child conflict, which were, in turn, related to increases in adolescent depressive symptoms. The association between fathers’ reports of marital conflict and adolescent depressive symptoms likely operated through mother–child conflict because mothers are typically tasked with managing marital stress and children’s behavior, especially considering previous evidence that fathers are more likely to withdrawal from family interaction in response to conflict (Katz and Gottman 1993). The significance of this pathway is not surprising given the moderate association between mothers’ and fathers’ reports of interparental conflict. Theoretically, parents are reporting on the same conflictual interactions; however, their perceptions, and thus, their behaviors in response to those perceptions, have been known to vary in past work on interparental conflict (Kerig 1996).

Strengths and Limitations

The current study has noteworthy strengths that add to the literature in important ways. Overall, the findings highlights the complexity of the family system and how relationships are interdependent with one another. Additionally, we used a longitudinal approach spanning a particularly important developmental period for the onset of adolescent depressive symptoms. We selected this period on the basis that social, emotional, and cognitive changes in middle childhood predict future outcomes, such as depression, above and beyond the effects of adjustment during early childhood (Feinstein and Bynner 2004).

Nonetheless, the current study has limitations centered around self-report methodology, informants, and the sample. First, no observational methods were analyzed in the current study, which would help eliminate potential response bias from parent perceptions of multiple family relationships. Parents who perceive themselves as experiencing more conflict in one relationship have been shown to be more likely to perceive more conflict in other relationships (Montemayor 1983); positive associations between interparental and parent–child conflict in this study may be due, in part, to the same individuals reporting on both aspects of family functioning. Unfortunately, child perceptions of interparental conflict and parent–child conflict which would give additional insight into how children perceive and observe conflict in the family were not available in the SECCYD dataset. Additionally, we did not find evidence for significant child gender differences in our data, but future research may consider exploring differences by child gender further, as it is possible that more specific aspects of family conflict (e.g., negative affect), rather than a general assessment of the presence of conflict may uncover nuanced differences between girls and boys that predict the onset of depressive symptoms later in life. Finally, eligibility criteria excluded families with non-biological parents, single parents, and parents who separated between the first two time points (5th and 6th grade). This was done to ensure the same individuals reported on interparental and parent–child conflict; however, the exclusion criteria resulted in a subsample of families that were more stable, less ethnically diverse, and of higher socioeconomic status than the full original sample.

Parents play an important role in children’s emotional development into adolescence. Our findings support previous work that mothers tend to be responsible for managing family emotions during times of stress. We also find that mothers’ conflict interactions with their children serve as an important link between marital conflict and increases in adolescent depressive symptoms, above and beyond conflict interactions between fathers and children. Future research may benefit from gaining further insight into the specific features of mother–child conflict that are most predictive of adolescent depressive symptoms, such as negative affect or maternal sensitivity. The present study provides a glimpse into the ways family conflict can disrupt development during a time when family relations are evolving and maturing.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (2006). Attachments and other affectional bonds across the life cycle. Attachment across the life cycle (pp. 41–59). London: Routledge. 10.4324/9780203132470.

Amato, P. R. (1986). Marital conflict, the parent–child relationship and child self esteem. Family Relations: An interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 35(3), 403–410. https://doi.org/10.2307/584368.

Amato, P. R., & Rivera, F. (1999). Paternal involvement and children’s behavior problems. Journal of Marriage and Family, 61(2), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.2307/353755.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association.

Asarnow, J. R.(1992). Suicial ideating and attempts during middle childhood: Associations with perceived family stress and depression among child psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 21(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2101_6.

Auerbach, R. P., Ho, M. H., & Kim, J. C. (2014). Identifying cognitive and interpersonal predictors of adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(6), 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9845-6.

Baker, J. K., Fenning, R. M., & Crnic, K. A. (2011). Emotion socialization by mothers and fathers: Coherence among behaviors and associations with parent attitudes and children’s social competence. Social Development, 20(2), 412–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00585.x.

Bates, J., Maslin, C., & Frankel, K. (1985). Attachment security, mother-child interaction, and temperament as predictors of behavior-problem ratings at age three years. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1–2), 167–193. https://doi.org/10.2307/3333832.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238.

Birmaher, B., Ryan, N. D., Williamson, D. E., Brent, D. A., Kaufman, J., Dahl, R. E., & Nelson, B. (1996). Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(11), 1427–1439. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011.

Block, J. (1978). Another look at sex differentiation in the socialization behaviors of mothers and fathers. In J. Sherman & F. Denmark (Eds.), Psychology of Women: Future Directions of Research (pp. 29–87). New York: Psychological Dimensions.

Bradford, K., Vaughn, L. B., & Barber, B. K. (2008). When there is conflict: interparental conflict, parent-child conflict, and youth problem behaviors. Journal of Family Issues, 28(6), 780–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X07308043.

Braiker, H., & Kelley, H. (1979). Conflict in the development of close relationships. In R. Burgess & T. Huston (Eds.), Social Exchange and Developing Relationships (pp. 135–168). San Diego: Academic Press, Inc.

Branje, S. J., Hale, W. W., Frijns, T., & Meeus, W. H. (2010). Longitudinal associations between perceived parent-child relationship quality and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(6), 751–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9401-6.

Brenning, K. M., Soenens, B., Braet, C., & Bosmans, G. (2012). Attachment and depressive symptoms in middle childhood and early adolescence: Testing the validity of the emotion regulation model of attachment. Personal Relationships, 19(3), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01372.x.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Buehler, C., Benson, M. J., & Gerard, J. M. (2006). Interparental hostility and early adolescent problem behavior: The mediating role of specific aspects of parenting. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(2), 265–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00132.x.

Cole, D. A., Tram, J. M., Martin, J. M., Hoffman, K. B., Ruiz, M. D., Jacquez, F. M., & Maschman, T. L. (2002). Individual differences in the emergence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A longitudinal investigation of parent and child reports. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(1), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843X.111.1.156.

Collins, W. A., & Russell, G. (1991). Mother-child and father-child relationships in middle childhood and adolescence: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review, 11(2), 99–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(91)90004-8.

Connor, J. J., & Rueter, M. A. (2006). Parent-child relationships as systems of support or risk for adolescent suicidality. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(1), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.143.

Cooksey, E., & Fondell, M. (1996). Spending time with his kids: effects of family structure on fathers’ and children’s lives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58(3), 693–707. https://doi.org/10.2307/353729.

Cox, M. J., Paley, B., & Harter, K. (2001). Interparental conflict and parent–child relationships. In J. H. Grych & F. D. Fincham (Eds.), Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 249–272). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511527838.011.

Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2002). Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process‐oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(5), 31–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00003.

Cummings, E. M., Davies, P. T., & Simpson, K. S. (1994). Marital conflict, gender, and children’s appraisals and coping efficacy as mediators of child adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 8(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.8.2.141.

Cummings, E., Keller, P. S., & Davies, P. T. (2005). Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(5), 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x.

Cummings, E. M., Geoke-Morey, M. C., & Papp, L. M. (2003). Children’s responses to everyday marital conflict tactics in the home. Child Development., 74(6), 1918–1929. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00646.x.

Curtin, S. C, Warner, M., & Hedegaard, H. (2016). Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS data brief, no 241. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics.

Davidov, M., & Grusec, J. (2006). Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development, 77(1), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x.

Davies, P., & Cummings, E. (1998). Exploring children’s emotional security as a mediator of the link between marital relations and child adjustment. Child Development, 69(1), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.2307/1132075.

Easterbrooks, M. A., & Emde, R. N. (1988). Marital and parent-child relationship: Role of affect in the family system. In R. A. Hinde & J. Stevenson-Hinde (Eds), Relationship within families: Mutual influences (pp. 83–103). New York: Oxford University Press.

Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Reiser, M., & Guthrie, I. K. (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72(4), 1112–1134. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00337.

Eisenberg, N., & Morris, A. S. (2002). Children’s emotion-related regulation. In R. V. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior, Vol. 30, (pp. 189–229). San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press.

El-Sheikh, M., Harger, J., & Whitson, S. M. (2001). Exposure to interparental conflict and children’s adjustment and physical health: the moderating role of vagal tone. Child Development, 72(6), 1617–1636. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00369.

Erel, O., & Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 108–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108.

Erickson, R. J.(2005). Why emotion work matters: Sex, gender, and the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family Psychology, 67(2), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00120.x.

Feinstein, L., & Bynner, J. (2004). The importance of cognitive development in middle childhood for adulthood socioeconomic status, mental health, and problem behavior. Child Development, 75(5), 1329–1339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00743.x.

Feldman, R., Eidelman, A. I., & Rotenberg, N. (2004). Parenting stress, infant emotion regulation, maternal sensitivity, and the cognitive development of triplets: A model for parent and child influences in a unique ecology. Child Development, 75(6), 1774–1791. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00816.x.

Fincham, F. D. (2003). Marital conflict: correlates, structure, and context. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(1), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01215.

Frojd, A. S., Nissinen, E. S., Pelkonen, M. U., Marttunen, M. J., Koivisto, A. M., & Kaltiala-Heino, R. (2008). Depression and school performance in middle adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Adolescence, 31(4), 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.08.006.

Gonzales, N. A., Pitts, S. C., Hill, N. E., & Roosa, M. W. (2000). A mediational model of the impact of interparental conflict on child adjustment in a multiethnic, low-income sample. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(3), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.14.3.365.

Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Fremmer-Bombik, E., Kindler, H., Scheuerer-Englisch, H., & Zimmermann, P. (2002). The uniqueness of the child-father attachment relationship: Fathers’ sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16-year longitudinal study. Social Development, 11(3), 307–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00202.

Grych, J. H.(2005). Interparental conflict as a risk factor for child maladjustment: Implications for the development of prevention programs. Family Court Review, 43(1), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1617.2005.00010.x.

Grych, J. H., Fincham, F. D., Jouriles, E. N., & McDonald, R. (2000). Interparental conflict and child adjustment: Testing the mediational role of appraisals in the cognitive‐contextual framework. Child Development, 71(6), 1648–1661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00255.

Hallfors, D. D., Waller, M. W., Bauer, D., Ford, C. A., & Halpern, C. T. (2005). Which comes first in adolescence—sex and drugs or depression? American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 29(3), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.002.

Harold, G. T., & Conger, R. D. (1997). Marital conflict and adolescent distress: The role of adolescent awareness. Child Development, 68(2), 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01943.x.

Harold, G. T., Osborne, L. N., & Conger, R. D. (1997). Mom and dad are at it again: Adolescent perceptions of marital conflict and adolescent psychological distress. Developmental Psychology, 33(2), 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.2.333.

Hetherington, E. M. (1992). I. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 57(2–3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1992.tb00300.x.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jekielek, S. M. (1998). Parental conflict, marital disruption and children’s emotional well-being. Social Forces, 76(3), 905–936. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/76.3.905.

Katz, L. F., & Gottman, J. M. (1993). Patterns of marital conflict predict children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 29(6), 940–950. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.29.6.940.

Katz, L. F., & Gottman, J. M. (1996). Spillover effects of marital conflict: in search of parenting and coparenting mechanisms. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1996(74), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219967406.

Kerig, P. K. (1996). Assessing the links between interpersonal conflict and child adjustment: The conflicts and problem-solving scales. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(4), 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.10.4.454.

Kerns, K. A., Aspelmeier, J. E., Gentzler, A. L., & Grabill, C. M. (2001). Parent–child attachment and monitoring in middle childhood. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.69.

Kerns, K. A., Tomich, P. L., Aspelmeier, J. E., & Contreras, J. M. (2000). Attachment-based assessments of parent–child relationships in middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 36(5), 614–626. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.614.

Kline, T. (2005). Psychological testing: A practical approach to design and evaluation. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s depression inventory: Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems.

Krishnakumar, A., & Buehler, C. (2000). Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta‐analytic review. Family Relations, 49(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00025.x.

Lamb, M. E. (1997). The development of father-infant relationships. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (pp. 104-120). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Lamb, M. E. (ed.) (2004). The role of the father in child development. New York: Wiley.

Lewis, C., & Lamb, M. E. (2003). Fathers’ influences on children’s development: the evidence from two-parent families. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 18(2), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173485.

Loeber, R., & Hay, D. (1997). Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology, 48(1), 371–410. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.371.

Margolin, G., Christensen, A., & John, R. S. (1996). The continuance and spillover of everyday tensions in distressed and nondistressed families. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(3), 304321. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.304.

Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & Oliver, P. H. (2004). Links between marital and parent–child interactions: Moderating role of husband-to-wife aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 16(3), 753–771. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404004766.

Messer, S. C., & Gross, A. M. (1995). Childhood depression and family interaction: A naturalistic observation study. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 24(1), 77–88.

Meth, R. L., Pasick, R. S., Gordon, B., Allen, J. A., Feldman, L. B., & Gordon, S. (1990). The Guilford family therapy series. Men in therapy: The challenge of change. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Mikulincer, M., Florian, V., Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2002). Attachment security in couple relationships: A systemic model and its implications for family dynamics. Family Process, 41(3), 405–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01074.x.

Montemayor, R. (1983). Parents and adolescents in conflict: All families some of the time and some families most of the time. Journal of Early Adolescence, 3(1–2), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01074.x.

Montemayor, R., & Hanson, E. (1985). A naturalistic view of conflict between adolescents and their parents and siblings. Journal of Early Adolescence, 5(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431685051003.

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Sessa, F. M., Avenevoli, S., & Essex, M. J. (2002). Temperamental vulnerability and negative parenting as interacting predictors of child adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00461.x.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2018). Mplus User’s Guide, Version 8. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

NSDUH. (2013). Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. Retrieved 11/13/2014 from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files.

Owen, M. T., & Cox, M. J. (1997). Marital conflict and the development of infant–parent attachment relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 11(2), 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.11.2.152.

Paikoff, R. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1991). Do parent-child relationships change during puberty? Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.47.

Parke, R. D., & Tinsley, B. J. (1987). Family interaction in infancy. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Wiley series on personality processes. Handbook of infant development (pp. 579–641). Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Peterson, J. L., & Zill, N. (1986). Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavior problems in children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 48(2), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.2307/352397.

Pianta, R. C. (1992). Child-parent relationship scale. Unpubished measure, University of Virginia.

Raffaelli, M., Crockett, L. J., & Shen, Y. L. (2005). Developmental stability and change in self-regulation from childhood to adolescence. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 166(1), 54–76. https://doi.org/10.3200/GNTP.166.1.54-76.

Rands, M., Levinger, G., & Mellinger, G. D. (2016). Patterns of conflict resolution and marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 2(3), 297–321.

Repetti, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 330–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.330.

Richardson, R. A., Galambos, N. L., Schulenberg, J. E., & Petersen, A. C. (1984). Young adolescents’ perceptions of the family environment. Journal of Early Adolescence, 4(2), 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431684042003.

Sands, R. G., & Dixon, S. L. (1986). Adolescent crisis and suicidal behavior: dynamics and treatment. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 3(2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00757218.

Scanlon, N. M., & Epkins, C. C. (2015). Aspects of mothers’ parenting: Independent and specific relations to children’s depression, anxiety, and social anxiety symptoms. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(2), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9831-1.

Shek, D. T. (1998). A longitudinal study of the relations between parent-adolescent conflict and adolescent psychological well-being. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 159(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221329809596134.

Sheeber, L., Hops, H., Alpert, A., Davis, B., & Andrews, J. (1997). Family support and conflict: Prospective relations to adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25(4), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025768504415.

Steinberg, L. (2001). We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.00001.

Steinberg, L., & Silk, J. S. (2002). Parenting adolescents. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1: Children and parenting (pp. 103–133). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sturge-Apple, M. L., Davies, P. T., Cicchetti, D., & Cummings, E. M. (2009). The role of mothers’ and fathers’ adrenocortical reactivity in spillover between interparental conflict and parenting practices. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014198.

Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2–3), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01276.x.

Trentacosta, C. J., Hyde, L. W., Shaw, D. S., Dishion, T. J., Gardner, F., & Wilson, M. (2008). The relations among cumulative risk, parenting, and behavior problems during early childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(11), 1211–1219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01941.x.

Tucker, C. J., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2003). Conflict resolution: links with adolescents’ family relationships and individual well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 24(6), 715–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x03251181.

Valiente, C., Fabes, R. A., Eisenberg, N., & Spinrad, T. L. (2004). The relations of parental expressivity and support to children’s coping with daily stress. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.97.

White, H. R., Johnson, V., & Buyske, S. (2000). Parental modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring alcohol and cigarette use: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse, 12(3), 287–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00056-0.

Yeung, W. J., Sandberg, J. F., Davis-Kean, P. E., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Children’s time with fathers in intact families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(1), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00136.x.

Yogman, M. W., Kindlon, D., & Earls, F. (1995). Father involvement and cognitive/behavioral outcomes of pre-term infants. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(1), 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199501000-00015.

Zimet, D. M., & Jacob, T. (2001). Influences of marital conflict on child adjustment: Review of theory and research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 4(4), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013595304718.

Acknowledgements

The archival NICHD Study of Early Child Care was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institure of Child Health and Human Development (U01 HD01897).

Author Contributions

O.A.S.: designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. J.A.N.: assisted and collaborated with the design of the study, data analyses, and writing of the manuscript. M.J.A.: assisted with writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for the current study was provided by The University of Texas at Dallas. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, O.A., Nelson, J.A. & Adelson, M.J. Interparental and Parent–Child Conflict Predicting Adolescent Depressive Symptoms. J Child Fam Stud 28, 1965–1976 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01424-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01424-6