Abstract

Objectives

Suicide is a leading causes of death for adolescents, and is a developmental period with the highest rates of suicide attempts. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth are a high-risk population for suicidal ideations and behaviors when compared with their non-LGBTQ counterparts. However, a dearth of research exists on the protective factors for suicidal ideation and attempts specifically within the LGBTQ population. The current study proposes a model in which peer victimization, drug use, depressive symptoms, and help-seeking beliefs predict suicidal ideation and attempts among a statewide sample of LGBTQ adolescents.

Methods

Among 4867 high school students in 20 schools, 713 self-identified as LGBTQ and had higher rates of attempts and ideation than their non-LBGTQ peers. Two logistic regression analyses were used to predict suicidal ideation and attempts among the 713 LGBTQ students (M = age 15 years).

Results

Results indicated that intentions to use drugs, peer victimization, and elevated depressive symptoms predicted both suicidal ideation and attempts. Additionally, help-seeking beliefs predicted suicidal attempts but not ideation, while the interaction of help-seeking beliefs and depressive symptoms significantly predicted suicidal ideation.

Conclusions

These findings underscore the importance of increasing access to effective treatment services for depression and promoting safe and accepting school and community cultures for LGBTQ youth in particular.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Suicide is a critical public health concern. In 2016, suicide was the tenth overall leading cause of death in the United States, with almost 45,000 people dying by suicide (CDC 2016). Adolescence has been identified as a key suicide prevention window period (Wyman 2014), with suicide being the second leading cause of death among adolescents ages 10–24 years (CDC 2016). In addition to high rates of suicide deaths among adolescents, the prevalence of suicide risk behaviors have been rising. From 2007 to 2017, rates of suicidal ideation and suicide planning significantly increased among high school students across the United States (CDC 2017). In an effort to guide suicide prevention work, the U.S. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (U.S. Surgeon General 2001) and the Institute of Medicine (Goldsmith et al. 2002) identified lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning (LGBTQ) youth as a particularly high-risk population for suicidal ideations and behavior. Decades of research, as well as recent data, have consistently found that LGBTQ youth are at greater risk of experiencing suicidal ideations and attempts when compared to their heterosexual counterparts (CDC 2017; Garofalo et al. 1999; Haas et al. 2010).

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors range from seriously considering suicide, creating a suicide plan, to making a suicide attempt. Many more people seriously consider suicide or make a suicide attempt than die by suicide, with some researchers estimating about 25 attempts for every suicide death and three people with suicidal ideation for every person with an attempt (Goldsmith et al. 2002; Nock et al. 2008). Especially considering the variance in these reported rates, it is critical to understand the differences in predictors and mechanisms between those who present with suicidal ideation and those who attempt suicide. A prior suicide attempt is one of the most reliable predictors of future attempts and death by suicide in general populations (Bostwick et al. 2016).

Past research has often cited risk factors for suicide that are actually risk factors for suicidal ideation, and not for the progression from ideation to attempts (Klonsky and May 2014). For instance, mental health disorders such as depression and other mood disorders are very strongly associated with suicidal ideation when compared to those who have never been suicidal, but fail to distinguish ideators from attempters (Kessler et al. 1999). This general pattern was also found in literature examining the suicide risk factors of hopelessness and impulsivity (Klonsky and May 2010; Nock and Kazdin 2002). This may be because, historically, suicide theories and research have conflated the question of why people have suicidal desires with why people act on these desires (Durkheim 1951; Shneidman 1993).

Theories and empirical research over the last decade have taken on an ideation-to-action framework and have begun to offer differing explanations for suicidal thoughts and the capability to act on these thoughts (Joiner 2005; Klonsky and May 2015). Recent research has found that among adolescents, hopelessness and depression were elevated among individuals who experienced suicidal ideations (Taliaferro and Muehlenkamp 2014), whereas a history of self-injury and alcohol use were indicative of individuals who attempted suicide (O’Brien et al. 2014). However, there is a paucity of literature that addresses the risk and protective factors separately for suicidal ideations and attempts among the LGBTQ adolescent population.

The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS) may help us understand the mechanisms by which LGBTQ youth are at greater risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior (Joiner 2005). The IPTS posits that suicidal ideation is influenced by two interpersonal experiences: feeling that one does not belong to meaningful relationships and groups (i.e., thwarted belongingness) and that one is a burden on others (i.e., perceived burdensomeness; Joiner 2005). Thwarted belongingness is characterized by feelings of loneliness and is commonly reported by LGBTQ youth due to LGBTQ-related victimization and bullying experiences (Kosciw et al. 2012). Perceived burdensomeness is characterized by self-hatred and feeling like a liability to others, which is also experienced by LGBTQ youth, specifically when “coming out” to their friends and family (Baams et al. 2015; Hilton and Szymanski 2011; Oswald 1999). Substantial empirical evidence links thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness to suicidal ideation and behavior (Joiner et al. 2012; Van Orden et al. 2006). Research shows the combined experience of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness confers greater risk for suicidal ideation and behavior, even after controlling for strong covariates including depression (Joiner et al. 2009; Van Orden et al. 2008). While research on the IPTS and mechanism for risk is well established, the differing mechanisms associated with suicidal ideation and behaviors among LGBTQ youth remain relatively understudied.

In addition to the IPTS, the Minority Stress Theory (MST) may shed some light on the nature of suicide among LGBTQ youth (Meyer 1995). The MST posits that individuals of marginalized identities (e.g., sexual or gender minority) experience chronic stress due to stigmatizing social contexts (Meyer 1995). Internalized bias, specifically internalized homophobia, is a common manifestation of minority stress characterized by individuals with sexual minority identities internalizing societal homophobia. This experience is immensely and chronically distressing, and contributes to upholding oppressive norms (Meyer 2003; Newcomb and Mustanski 2016; Szymanski et al. 2008). MST has provided a useful framework for understanding the relations among the marginalization experiences of sexual minority youth and associated poor outcomes (Hatzenbuehler 2009; Lick et al. 2013). This distress may help account for the overrepresentation of LGBTQ youth among students grappling with high levels of anxiety, depression, and risky drug use patterns (Kosciw et al. 2016).

LGBTQ students are disproportionately victimized in schools, with 85.2% of students reporting sexuality-based verbal harassment over the past year, with 39.7% at extremely high frequencies, according to a U.S. national sample (Kosciw et al. 2016). Regarding physical harassment, 27.0% of students from this sample reported being physically victimized at school based on their sexuality, with 7.5% reporting victimization with high frequency (Kosciw et al. 2016). These rates of victimization are also consistent across other forms of peer violence such as cyberbullying, relational aggression, and sexual harassment (Kosciw et al. 2016). Additionally, LGBTQ students in this sample reported their sexual orientation being the most common focus of the attack (Kosciw et al. 2016). A recent study of 248 sexual minority youth in Chicago (ages 16–20 years at baseline) found that, over the course of four years, 10% of the sample experienced moderate and increasing peer victimization, about 5% experienced steadily high peer victimization, and about 20% experienced high but declining peer victimization (Mustanski et al. 2016). This study highlights the chronicity of at least moderately frequent victimization experiences for about one third of the sample.

In addition to peer victimization, depression has been shown to be associated with suicide in youth. Sixty percent of adolescent suicide victims had a depressive disorder at the time of death (Brent et al. 1999). Research suggests that depression is the strongest predictor of suicidal ideation (Cash and Bridge 2009). In one study, 85% patients with major depressive disorder had suicidal ideation (Kovacs et al. 1993). This is especially concerning among LGBTQ youth as LGBTQ youth show increased levels of depression compared to non-LGBTQ youth (Kosciw et al. 2012).

Behavioral health outcomes, including drug use, are also concerning as they relate to chronic experiences of minority stress (Kosciw et al. 2016). Specifically, LGBTQ youth are at a higher risk for problematic use of drugs when compared to their non-LGBTQ peers (CDC 2016; Kosciw et al. 2016). Further, a recent meta-analysis identified a significant association between identity-related distress and drug use among LGBTQ adolescents, highlighting the role of minority stress (Goldbach et al. 2014). Another explanation scholars have explored for the prevalence of drug use is affiliations with deviant peers. LGBTQ youth often form or enter deviant (i.e. isolated) peer groups resulting from victimization experiences perpetrated by mainstream-affiliated peers (Hueber et al. 2015). Several studies have found that students’ bond (defined as attachment and commitment; Catalano et al. 1996) to their school community facilitates drug use prevention. The model proposes that when students feel attached and committed to their school community, they are therefore socially obligated to uphold norms and standards (Fergusson et al. 2002; Maddox and Prinz 2003). However, once students become deviant or isolated and no longer feel this obligation, drug use can proliferate and even become a relative norm within deviant groups (Fergusson et al. 2002; Maddox and Prinz 2003).

Additionally, given that LGBTQ students have likely experienced chronic stressors, there is substantial evidence supporting drug use functioning as a coping mechanism. One study found that among college students, negative affect and coping motives mediated the pathway from experiences of discrimination to problematic alcohol use (Dawson et al. 2005). However, coping experiences of LGBTQ adolescents is an understudied area in the extant literature. Goldbach and Gibbs (2015) employed a qualitative design to explore the unique coping processes employed by 48 racially diverse sexual minority students. Regarding relevant constructs, their findings were consistent with studies of LGB adults; adolescents also reported using drugs to cope with effects of minority stress, among other strategies. With respect to compounding experiences of minority stress, a study of LGB adults found that discrimination on this basis alone did not predict increased odds of developing a drug use disorder, but LGB-related discrimination in combination with racially or gender-based discrimination did increase risk of developing a disorder (McCabe et al. 2010). How drug use fits into the larger experience of minority stress among LGBTQ youth struggling with suicide remains relatively understudied. Nonetheless, across populations, drug use heightens risk for death by suicide both acutely and distally (Vijayakumar et al. 2011). Given the prevalence of direct exposure to bias-based aggression like homophobia, it is unsurprising that LGBTQ youth face an elevated risk of developing an array of internalizing mental health symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression, and suicidality; McDermott et al. 2017) as well as externalizing symptoms (e.g., problematic drug use; Goldbach et al. 2014).

Research on protective factors has identified willingness to seek help as a powerful buffer against the development or escalation of negative outcomes among youth generally, and sexual minority youth in particular (Clement et al. 2015; McDermott and Roen 2016; McDermott et al. 2017). Even if students are grappling with mental or behavioral health issues, if they feel positively about seeking help, they are more likely to do so and see more positive outcomes in the future (McDermott et al. 2017). Feeling comfortable seeking help is closely related to the real or perceived social supports available. Youth in general report preferring to turn to peers rather than adults when contemplating suicide, despite evidence suggesting that aid from an adult or mental health professional may be more beneficial (Eisenberg et al. 2016; Wyman et al. 2008). Youth experiencing suicidal thoughts who disclose and seek help from adults are more likely to perceive that adults will respond positively to suicide concern and that their peers and family would support their help-seeking action (Pisani et al. 2012). Among LGBTQ youth, friends, and especially LGBTQ friends, may be more supportive than family members (Doty et al. 2010; McDermott 2015).

These findings align with the IPTS in that social support buffers against feelings of thwarted belongingness and provide a realistic pathway for seeking help. However, help seeking likely becomes most relevant during times of distress. For students at high risk, willingness to seek help from social supports may moderate pathways linking minority stress to mental health issues like suicidal thoughts and behaviors. This also aligns with the extant literature on social support generally and among LGBTQ youth, which often conceptualizes and models these factors as interaction effects (Luthar et al. 2000; Hatchel et al. 2018; Hatchel et al. 2018). Therefore, promoting and normalizing help seeking represents an important avenue for attenuating grave outcomes associated with minority stress, such as death by suicide.

For a number of reasons (feasibility among them), a dearth of research exists on the relations among the aforementioned constructs specifically among LGBTQ youth. To this end, the current study proposes a model in which peer victimization, drug use, depressive symptoms, and help-seeking beliefs predict suicidal ideation and behavior among a statewide sample of LGBTQ adolescents. The following hypotheses and research questions were developed: (H1) Peer victimization will predict both suicidal ideation and behavior. (H2) Likelihood of future drug use will predict both suicidal ideation and behavior. (H3) Depressive symptoms will predict both suicidal ideation and behavior. (H4) Help-seeking beliefs will predict both suicidal ideation and behavior. (H5) Help-seeking beliefs will moderate the relation between depressive symptoms and suicidality. (RQ1) How will the predictors vary in their effects on ideation vs. behavior? (RQ2) Will the models vary as a function of LGBTQ identity?

Method

Participants

Participants were a sample of students enrolled in 20 high schools (N = 4867) participating in baseline data collection for a randomized clinical trial testing the effects of Sources of Strengths (LoMurray 2005; Wyman et al. 2010). Self-reported sexual orientation was straight (83.5%), gay or lesbian (2%), bisexual (6.9%), questioning (3.2%), and other (2.5%). Only students who reported not being heterosexual and/or reported being transgender were included in the LGBTQ models (N = 713). Students in this sample were predominantly Hispanic (43.4%), White (40.3%), and Multiracial (8.1%). Ages ranged from 12 to 18 years (M= 15 years) and most were in 9th grade (42.6%), 10th grade (38.4%) and 11th grade (18.2%). Self-reported gender was male (23.0%), female (66.3%), transgender (4.3%), and other (5.9%). The non-LGBTQ sample (N = 4154) was also largely Hispanic (47.0%) and White (44.0%). Ages ranged from 12 to 18 years (M= 15 years) and most were in 9th grade (42.1%), 10th grade (38.8%) and 11th grade (18.2%). Self-reported gender was male (54.8%), female (44.6%).

Procedure

The study was approved by institutional review boards (IRBs). A waiver of documentation of parent consent was approved by the IRBs such that all parents received information letters and could opt their child out of participation by returning a form, calling the school or emailing research staff. Eligible students were provided information about the study and those who provided verbal assent were enrolled to complete online surveys. Data collection occurred during regular class times with the supervision of one of the researchers in each classroom. Most students completed an online survey, but paper surveys were used for Spanish speaking students and if there were connectivity issues with the online survey. Students were provided with a log-in id and password that was unique to each student, and they did not enter their names. Students could skip any questions that they did not feel comfortable answering and could stop participation at any point. They were provided with resources at the end of the survey for suicidal concerns, depression issues, and sexual violence. Data collection was completed during the fall of 2017 and a report with school level outcomes was offered to school administrators as part of the study. All students and parents were informed that survey responses would be de-identified and therefore no individual data would be reviewed for the purpose of crisis intervention or referrals.

Measures

Help-seeking beliefs

Help-seeking beliefs were measured with the Help-Seeking from Adults at School scale (Schmeelk‐Cone et al. 2012; Wyman et al. 2010). The measure assesses students’ beliefs and perceived norms about getting help for emotional distress. The scale consists of seven items beginning with the stem, “If I was really upset and needed help…” students responded to questions covering intentions to seek help (“I would talk to a counselor or other adult at school”), expectations of receiving help (“I believe a counselor or other adult at school could help me”), and perceived norms about seeking help (“My friends…” or “My family……would want me to talk to a counselor or other adult at school”). Students responded to each item using a four-point Likert scale (Strongly Disagree = “1” through Strongly Agree = “4”). The Cronbach’s alpha was .87 for the LGBTQ sample and .89 for the non-LGBTQ sample.

Suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation during the past 6 months was measured with the question “…have you seriously considered suicide?” Student responses were: No = “0” or Yes = “1.”

Suicidal attempts

Suicidal attempts during the past 6 months were measured with one question “…how many times did you actually attempt suicide?”. Students were only asked whether they attempted suicide if they answered “Yes” to either the suicidal ideation or planning questions. Response options included: 0 times “0”, 1 time “1”, 2 or 3 times “2”, 4 or 5 times “3”, and 6 or more times “4”. Responses were dichotomized.

Peer victimization

Victimization from peers was assessed using the 4-item University of Illinois Victimization Scale (UIVS; Espelage and Holt 2001). Students are asked how often the following things have happened to them in the past 30 days (i.e., “Other students called me names”, “Other students made fun of me”, “Other students picked on me”, and “I got hit and pushed by other students”). Response options include: “Never”, “1 or 2 times”, “3 or 4 times”, “5 or 6 times”, and “7 or more times.” Construct validity of this measure was supported through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses and convergence with peer nominations of victimization (Espelage and Holt 2001). Higher scores indicate more self-reported victimization. A Cronbach alpha coefficient of .86 was found for the LGBTQ sample and .89 for the non-LGBTQ sample.

Likelihood of future drug use

Drug use was measured with 4 questions asking students how likely they would engage in drug use behaviors during the next 6 months. Students were asked “How likely are you in the next 6 months to …”: (1) “smoke cigarettes”; (2) “get drunk or very high on alcohol”; (3) “use marijuana”; and (4) “use prescription drugs to get high.” Response options ranged from: Not at all likely “0”; Somewhat likely “1”; and Very likely “2.” We did not ask about current alcohol and drug use because one of the IRBs viewed this behavior as illegal and therefore unethical without further investigation. A Cronbach alpha coefficient of .76 was found for the LGBTQ sample and .75 for the non-LGBTQ sample.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive Symptoms were measured using the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ; Angold et al. 1996). The SMFQ (13 items) has well-established content and criterion-related validity, with significant and high correlations between the SMFQ and the longer version (MFQ), the Children’s Depression Inventory, and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. Scores ranged from 0 to 26, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms (Angold et al. 1995). This scale asks adolescents to indicate how much they felt or acted certain ways in the last 30 days. Examples include: “I felt miserable or unhappy”, and “I thought nobody really loved me”. Response options were: Never “0”; Sometimes “1”; and Most of the time “2” with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. A Cronbach alpha coefficient was .94 for both samples.

Data Analyses

Hierarchical logistic regression analyses were completed with IBM SPSS 24.0 to determine whether the set of variables and interactions predicted the health outcomes of interest (i.e., suicidal ideation and attempts). The assumptions for normality were acceptable for all variables other than suicidal attempts which was dichotomized. Two main regression analyses were modeled for both samples—one with suicidal ideation (Y/N) as the outcome and the other with suicide attempts (Y/N) as the outcome. For all models, (1) peer victimization was added to the first step, followed by (2) help-seeking beliefs, (3) depressive symptoms, and (4) likelihood of future drug use, then the interaction term between (5) depressive symptoms and help-seeking attitudes was added to the third step. Age and sex were controlled for as covariates. All predictors were centered before calculating product terms to protect against multicollinearity (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). The significant interaction effects were illustrated by graphing the regression equation at relevant beta values of the moderator (i.e., help-seeking beliefs).

Missing data ranged from 2.5 to 5.0% depending on the item. Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test indicated that the data were missing at random (χ2 = 463.33, p= .34). This enables the utilization of imputation with minimal risk of biased estimation. The maximization estimation method was implemented to impute the missing data as it is believed to be superior to methods like list-wise deletion or mean substitution (Schlomer et al. 2010).

Results

Descriptive statistics are depicted in Table 1 and bivariate correlates are shown in Table 2. In the sample of 713 students identifying as LGBTQ, 42% reported considering suicide in the past six months and 29% reported attempting suicide at least once in the past six months. In contrast, via the sample of 4154 non-LGBTQ identified youth, 14% reported suicidal ideation and 9% reported suicide attempts.

LGBTQ Sample

Suicidal ideation

Results of the analyses demonstrated that the set of five predictors successfully distinguished between LGBTQ adolescents who reported suicidal ideation and those who did not, χ2 (7) = 261.78, p< .001. The predictors, as a whole, accounted for 44% of the variance in suicidal ideation. Specifically, the model correctly predicted the outcome category for 83% of adolescents who were not actively suicidal and 69% for those who were. This offered an overall prediction success rate of 77%.

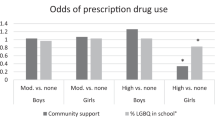

In the first model, tests of the individual parameters revealed peer victimization differentiated between those who reported suicidal ideation and those who did not (b = .42, z = 29.89, p < .001). In the second model, depressive symptoms was the strongest predictor (b = 2.44, z = 129.04, p < .001). Reported depressive symptoms increased the probability of suicidal ideation by a multiplicative factor of 11.44; that is, LGBTQ adolescents were almost 12 times more likely to endorse suicidal ideation if they were experiencing depressive symptoms. Greater likelihood of future drug use also predicted suicidal ideation; the more future drug use reported, the more likely they were to report ideation (b = .81, z= 12.84, p< .001). Specifically, in the order of roughly 2 times more likely than their peers who did not report future drug use. The interaction term between help-seeking beliefs and depressive symptoms significantly predicted suicidal ideation (b = .87, z= 6.18, p< .01). Plotting of the relationship between depression and ideation for students with varying levels of help-seeking beliefs (–1 SD, Mean, +1 SD) showed that those who reported higher help-seeking beliefs and more depressive symptoms were more likely to endorse ideation than those with lower help-seeking beliefs (Fig. 1). See Table 3 for a summary.

Suicide attempts

The set of five predictors successfully distinguished between LGBTQ adolescents who reported suicidal behaviors and those who did not, χ2 (7) = 111.09, p< .001. The predictors accounted for 22% of the variance in suicidal behavior. Precisely, the model correctly predicted the outcome category for 90% of adolescents who did not endorse suicidal behavior and 28% for those who did. This offered an overall prediction success rate of 72%.

In the first model, tests of the individual parameters revealed peer victimization differentiated between those who reported suicidal ideation and those who did not (b = .52, z= 33.66, p< .001). In the second model, three of the individual parameters significantly differentiated between those who reported suicidal behavior and those who did not. Help-seeking beliefs reduced the probability of reporting suicidal behavior (b = −.23, z= 1.87, p< .05). These beliefs decreased the probability of suicidal behavior by multiplicative factor of .80. Depressive symptoms were the strongest predictor (b = 1.15, z= 41.55, p< .001). Stated depressive symptoms increased the probability of suicidal behavior by a multiplicative factor of 3.16. Specifically, LGBTQ adolescents were at least three times more likely to endorse suicidal behavior if they were experiencing depressive symptoms. Greater likelihood of future drug use and peer victimization also predicted suicidal behavior – the greater future drug use and peer victimization reported the more likely they were to report suicidal behavior (b = .55, z= 7.97, p< .01; and b = .29, z= 8.65, p< .01). In detail, LGBTQ adolescents were at 1.7 times more likely to endorse suicidal behavior if they reported future drug use and 1.3 times more likely if they reported being victimized by their peers. The interaction between help-seeking beliefs and depressive symptoms predicting suicide attempts was not significant. See Table 4 for a summary.

Non-LGBTQ Sample

Suicidal ideation

Results of the analyses demonstrated that the set of five predictors successfully distinguished between non-LGBTQ adolescents who reported suicidal ideation and those who did not, χ2 (7) = 1089.15, p< .001. All of the predictors accounted for 46% of the variance in suicidal ideation. Precisely, the model correctly predicted the outcome category for 97% of adolescents who were not actively suicidal and 44% for those who were. This offered an overall prediction success rate of 89%.

Peer victimization differentiated between those who reported suicidal ideation and those who did not in the first model (b = .77, z= 194.84, p< .001). Non-LGBTQ adolescents were at least 2 times more likely to endorse suicidal ideation if they were reported being victimized by peers. In the second model, test of individual parameters revealed three variables that predicted suicidal ideation—depressive symptoms (b = 2.77, z= 481.97, p< .001) which increased the probability of suicidal ideation by a multiplicative factor of 15.95; future drug use (b = 1.05, z= 54.84, p< .001) which increased the probability of suicidal ideation by a multiplicative factor of 2.86; and peer victimization (b = .32, z= 21.39, p< .001) which increased the probability of suicidal ideation by a multiplicative factor of 1.37. The interaction effect was not significant (see Table 3).

Suicide attempts

The set of five predictors effectively distinguished between non-LGBTQ adolescents who reported suicidal behaviors and those who did not, χ2 (7) = 638.79, p< .001. The predictors accounted for 33% of the variance in suicidal behavior. Specifically, the model correctly predicted the outcome category for 98% of adolescents who did not endorse suicidal behavior and 28% for those who did. This offered an overall prediction success rate of 90%.

In the first model, peer victimization discriminated between those who reported suicidal behavior and those who did not (b = .70, z= 149.90, p< .001). Non-LGBTQ adolescents were at least two times more likely to endorse suicidal behavior if they were reported being victimized by peers. In the second model, test of individual parameters revealed three factors that predicted suicidal behavior—depressive symptoms (b = 1.97, z= 282.95, p< .001) which increased the probability of suicidal behavior by a multiplicative factor of 7.18; future drug use (b = .99, z= 49.59, p< .001) which increased the probability of suicidal ideation by a multiplicative factor of 2.68; and peer victimization (b = .30, z= 19.30, p< .001) which increased the probability of suicidal ideation by a multiplicative factor of 1.35 (see Table 4). In the third mode, the interaction term between help-seeking beliefs and depressive symptoms was not significant.

Discussion

This study further advanced the suicide literature by examining predictors of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among a relatively large sample of high school students. Consistent with previous research, this sample of LGBTQ students reported frequent suicidal ideation and attempts. More specifically, 40% of the sample reported suicidal ideation in the last six months, which is consistent with the 43% reported ideation in the past year in a nationally representative sample (Zaza et al. 2016). This difference could be partially explained by the reporting time difference of six months versus a year. The LGBTQ adolescents in our sample have a a higher prevalence of both suicidal ideation and attempts compared to their non-LGBTQ peers. Concerning suicide attempts, 29% of our sample reported attempting suicide in the last 6 months, which is consistent with 29% of LGBTQ youth who attempted in the last year in a nationally representative sample, which is much higher than the 6% of attempts by heterosexual youth (Zaza et al. 2016). This extraordinarily high rate of attempts is particularly alarming in light of evidence that each suicide attempt substantially increases risk for future attempts and death by suicide (Bostwick et al. 2016).

IPTS and MST were utilized to inform our understanding of factors that are associated with greater rates of suicidal ideation and attempts (Joiner 2005; Meyer 1995). IPTS suggests that LGBTQ youth are at greater risk for suicidal ideation because peer victimization and rejection increase thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness; MST points to the chronic stress associated with being a gender or sexual minority as a result of stigmatizing social contexts, such as school. Thus, depression, peer victimization, help-seeking beliefs and intent to use drugs were examined as predictors of both suicidal ideation and attempts. As hypothesized, LGBTQ youth who reported high levels of depression were significantly more likely to report suicidal ideation than LGBTQ youth with less depression. LGBTQ Youth with high levels of depression were three times more likely to attempt suicide in the last six months in comparison to LGBTQ youth with less depression. Of note, the differential prediction of depression between ideation and attempts is consistent with the research where depression and other mood disorders are very strongly associated with suicidal ideation when compared to those who have never been suicidal, but fail to distinguish ideators from attempters (Kessler et al. 1999).

Greater peer victimization experiences were predictive of both suicidal ideation and attempts. Higher rates of peer victimization and the associated adverse outcomes, including suicidal thoughts and attempts, among LGBTQ youth have been demonstrated by countless studies (Birkett et al. 2009; Huebner et al. 2015; Kosciw et al. 2012; Robinson and Espelage 2011; Ybarra et al. 2015). There is substantial empirical evidence linking general peer victimization and suicidal ideation and our results align well (Duong and Bradshaw 2014; Eisenberg et al. 2016; Livingston et al. 2015; Poteat et al. 2013). However, peer victimization did not predict suicidal ideation when the other predictors were added to the model. One interpretation of our findings is that elevated depression in particular explains the risk for ideation among LGBTQ youth, and that peer victimization may serve to precipitate attempts within this vulnerable group. That is, peer victimization may potentiate ideation-to-action. An important priority for future studies with LGBTQ populations is to prospectively study the transition from ideation to attempts.

It is worth noting that there is another dimension of victimization that our present study does not tap into, and that is the intention behind the aggression. Bias-based aggression, like homophobic bullying, may be better at predicting ideation in line with MST (Meyer 2003). This has been demonstrated by a number of other studies (Baams et al. 2015; Lea et al. 2014; Liu and Mustanski 2012; Russell et al. 2011; Whitaker et al. 2016). Our finding specific to peer victimization needs to be replicated, examined within a longitudinal framework, and interpreted with caution.

Like peer victimization, endorsement of help-seeking beliefs was differentially predictive of suicidal ideation and attempts, which did not support our initial hypothesis. Help-seeking beliefs did not predict ideation, but low help-seeking beliefs were associated with suicide attempts. It is possible that there is a correlation between low help-seeking beliefs, which include limited expectations of being helped, and hopelessness that is a well-established predictor of suicidal attempts. This is an association that should be explored further. When help-seeking beliefs were examined as a moderator of depression and suicidal ideation and attempts, this moderating effect was found only for ideation. Closer examination of the interaction between depression and help-seeking beliefs indicated that LGBTQ youth with the highest levels of depression and highest levels of positive help-seeking beliefs were modestly more likely to report suicidal ideation. This finding could indicate that youth who are willing to report ideation and depression on self-report measures might be seeking help given their heightened level of distress (McDermott et al. 2017). Another interpretation is that having both help-seeking beliefs and depressive symptoms was indicative of openness to reporting their ideation. The results are somewhat unintuitive since previous research has demonstrated that receiving support offers a buffering effect (Clement et al. 2015; McDermott and Roen 2016; McDermott et al. 2017). Help-seeking beliefs may be an important seqeula to receiving support, while not offering the same kind of effect. Future work should explore how to translate beliefs into actually receiving much needed support. In contrast, help-seeking did not moderate the association between depression and likelihood of a suicide attempt, which is another source of data that suggests a distinction between factors that increase likelihood of suicidal ideation and likelihood of attempts.

Concerning differences between LGBTQ adolescents and their non-LGBTQ peers, the data largely demonstrate similarities concerning predictors of both suicidal ideation and behavior. Elevated depression was associated with both suicidal ideation and attempts for both groups, as was higher likelihood of future alcohol and drug use as well as peer victimization. These findings align well with the extant literature (CDC 2016; Kosciw et al. 2016). The main between-group differences were associated with help-seeking beliefs, which predicted diminished reports of suicidal behavior among only LGBTQ adolescents. Likewise, the interaction between depressive symptoms and help-seeking beliefs on suicidal ideation only emerged for the LGBTQ group. Given the feelings of isolation, depression, and hopelessness that are not uncommon among LGBTQ adolescents (Kosciw et al. 2012), it is likely that having positive beliefs around help seeking is more powerful in attenuating one’s potential to act on suicidal thoughts. Similarly, since there is considerable stigma associated with both being LGBTQ and having mental health problems (Meyer 2003), it seems probable that this marginalized group is more likely to report their high levels of distress via discreet methods. Since there is a clear paucity of research on help-seeking beliefs among LGBTQ adolescents, these results should be interpreted with caution and replicated.

The public health significance of reducing youth suicidal attempts across general and specific high-risk populations is increasing. Suicide death rates have continued to rise from 2010 to 2015 (the last year reported), most notably for 10–14 year olds by 53% and for 15–19 year olds (CDC 2016) whose death rates have increased by 30%. Our findings of high rates of suicide ideation and attempts among LGBTQ youth is cause for concern and also demonstrate that depression, peer victimization, drug use, and help-seeking beliefs are all worthy of consideration for new prevention approaches among this high-risk population. First, our findings underscore the importance of increasing access to effective treatment services for depression and promoting safe and accepting school and community cultures. Of additional interest is our finding that positive help-seeking beliefs may be helpful for LGBTQ youth struggling with both ideation and depression. It is unclear how positive help-seeking beliefs and expectations can be promoted among diverse LGBTQ adolescents, and exploring this issue should be a priority for future research and intervention studies.

Limitations and Future Research

There are important limitations to our study. First, the data are cross-sectional and no conclusions can be made regarding directionality among the predictors and suicidal ideation or attempts. Future studies using longitudinal data are needed to disentangle the relationships uncovered in this study. Second, LGBTQ participants were examined as a homogenous group even though their experiences are likely to be diverse. Therefore, the findings of this study do not offer precise conclusions concerning how groups within the LGBTQ youth community may vary. Lastly, participants were selected from the state of Colorado, therefore findings may not generalize to a wider population at the state, national, or international level.

Future research will benefit from large scale longitudinal studies to uncover the distinct predictors and protective factors of suicidal ideation and attempts and, in particular, the transition from ideation to attempts. Studies with access to nationally representative samples will be needed to understand the higher risk of suicidality among LGBTQ youth. Specifically, research should focus on when and why individuals transition from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts (Klonsky et al. 2016). This knowledge will be essential to the creation of successful interventions and prevention programs geared towards those at a heightened risk, like LGBTQ youth.

The present study sought to advance the field by developing the literature on predictors of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among LGBTQ youth and their peers. Whereas a large number of prior studies have assessed mental health and drug use risk factors, a strength of our study was to assess the role of help-seeking beliefs, which incorporated expectations of receiving help and peer and family support for help seeking. Our finding regarding low help seeking and increased likelihood of attempts points to new directions for research and prevention. Another strength of the study was the relatively large sample of LGBTQ adolescents selected from 20 different schools across the state of Colorado with diverse levels of urban and rural development.

References

Angold, A., Costello, E. J., Messer, S. C., Pickles, A., Winder, F., & Silver (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5(4), 237–249.

Angold, A., Erkanli, A., Costello, E. J., & Rutter, M. (1996). Precision, reliability and accuracy in the dating of symptom onsets in child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37(6), 657–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01457.x.

Baams, L., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 688–696. https://doi.org/10.1037/a003899.

Birkett, M., Espelage, D. L., & Koenig, B. (2009). LGB and questioning students in schools: the moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 989–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1.

Bostwick, J. M., Pabbati, C., Geske, J. R., & McKean, A. J. (2016). Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(11), 1094–1100. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854.

Brent, D. A., Baugher, M., Bridge, J., Chen, T., & Chiapetta, L. (1999). Age- and sex-related risk factors for adolescent suicide. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(12), 1497–1505. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199912000-00010.

Cash, S. J., & Bridge, J. A. (2009). Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 21, 613–619. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833063e1.

Catalano, R. F., Kosterman, R., Hawkins, J. D., Newcomb, M. D., & Abbott, R. D. (1996). Modeling the etiology of adolescent substance use: a test of the social development model. Journal of Drug Issues, 26(2), 429–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204269602600207.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017) Youth Risk Behavior Survey—Data Summary & Trends Report: 2007–2017. Youth Risk Behavior Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trendsreport.pdf. Accessed 12 September 2018.

Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., & Thornicroft, G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000129.

Dawson, D. A., Grant, B. F., & Ruan, W. J. (2005). The association between stress and drinking: modifying effects of gender and vulnerability. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 40(5), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agh176.

Doty, N. D., Willoughby, B. L., Lindahl, K. M., & Malik, N. M. (2010). Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1134–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x.

Duong, J., & Bradshaw, C. (2014). Associations between bullying and engaging in aggressive and suicidal behaviors among sexual minority youth: the moderating role of connectedness. Journal of School Health, 84(10), 636–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12196.

Durkheim, E. (1951). Suicide: A study in sociology. New York: Free Press.

Eisenberg, M. E., McMorris, B. J., Gower, A. L., & Chatterjee, D. (2016). Bullying victimization and emotional distress: is there strength in numbers for vulnerable youth? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 86, 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.04.007.

Espelage, D. L., & Holt, M. K. (2001). Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 2(2–3), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1300/J135v02n02_08.

Fergusson, D. M., Swain-Campbell, N. R., & Horwood, L. J. (2002). Deviant peer affiliations, crime and substance use: a fixed effects regression analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(4), 419–430.

Garofalo, R., Wolf, R. C., Wissow, L. S., Woods, E. R., & Goodman, E. (1999). Sexual orientation and risk of suicide attempts among a representative sample of youth. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 153(5), 487–493. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.5.487.

Goldbach, J. T., & Gibbs, J. (2015). Strategies employed by sexual minority adolescents to cope with minority stress. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000124.

Goldbach, J. T., Tanner-Smith, E. E., Bagwell, M., & Dunlap, S. (2014). Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: a meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15(3), 350–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7.

Goldsmith, S. K., Pellmar, T. C., Kleinman, A. M. & Bunney, W. E. (2002). Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Haas, A. P., Eliason, M., Mays, V. M., Mathy, R. M., Cochran, S. D., D’Augelli, A. R., & Russell, S. T. (2010). Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(1), 10–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.534038.

Hatchel, T., Merrin, G. J., & Espelage, A. D. (2018). Peer victimization and suicidality among LGBTQ youth: the roles of school belonging, self-compassion, and parental support. Journal of LGBT Youth. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2018.1543036.

Hatchel, T., Subrahmanyam, K., & Negriff, S. (2018). Adolescent peer victimization and internalizing symptoms during emerging adulthood: the role of online and offline social support. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1286-y.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “Get Under the Skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016441.

Hilton, A. N., & Szymanski, D. M. (2011). Family dynamics and changes in sibling of origin relationship after lesbian and gay sexual orientation disclosure. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, 33(3), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-011-9157-3.

Huebner, D. M., Thoma, B. C., & Neilands, T. B. (2015). School victimization and substance use among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents. Prevention Science, 16(5), 734–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-014-0507-x.

Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Joiner, T. E., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Selby, E. A., Ribeiro, J. D., Lewis, R., & Rudd, M. D. (2009). Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 634–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016500.

Joiner, T. E., Ribeiro, J. D., & Silva, C. (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal behavior, and their co-occurrence as viewed through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 342–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412454873.

Kessler, R. C., Borges, G., & Walters, E. E. (1999). Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 617–626. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617.

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2010). Rethinking impulsivity in suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 40, 612–619. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.612.

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2014). Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators: a critical frontier for suicidology research. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12068.

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2015). The three-step theory (3ST): a new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8(2), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114.

Klonsky, E. D., May, A. M., & Saffer, B. Y. (2016). Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204.

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Bartkiewicz, M. J., Boesen, M. J., & Palmer, N. A. (2012). The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN.

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Giga, N. M., Villenas, C., & Danischewski, D. (2016). The 2015 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN.

Kovacs, M., Goldston, D., & Gatsonis, C. (1993). Suicidal behaviors and childhood-onset depressive disorders: a longitudinal investigation. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199301000-00003.

Lea, T., de Wit, J., & Reynolds, R. (2014). Minority stress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults in Australia: associations with psychological distress, suicidality, and substance use. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(8), 1571–1578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0266-6.

Lick, D. J., Durso, L. E., & Johnson, K. L. (2013). Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(5), 521–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613497965.

Liu, R. T., & Mustanski, B. (2012). Suicidal ideation and self-harm in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(3), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.023.

Livingston, N. A., Heck, N. C., Flentje, A., Gleason, H., Oost, K. M., & Cochran, B. N. (2015). Sexual minority stress and suicide risk: identifying resilience through personality profile analysis. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 321 https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000116.

LoMurray, M. (2005). Sources of strength facilitators guide: Suicide prevention peer gatekeeper training. Bismarck: The North Dakota Suicide Prevention Project.

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00164.

Maddox, S. J., & Prinz, R. J. (2003). School bonding in children and adolescents: conceptualization, assessment, and associated variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(1), 31–49.

McCabe, S. E., Bostwick, W. B., Hughes, T. L., West, B. T., & Boyd, C. J. (2010). The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 100(10), 1946–1952. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147.

McDermott, E. (2015). Asking for help online: Lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans youth, self-harm and articulating the ‘failed’self. Health, 19(6), 561–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459314557967.

McDermott, E., Hughes, E., & Rawlings, V. (2017). The social determinants of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth suicidality in England: a mixed methods study. Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdx135.

McDermott, E., & Roen, K. (2016). Queer youth, suicide and self-harm: troubled subjects, troubling norms. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 38–56.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Mustanski, B., Andrews, R., & Puckett, J. A. (2016). The effects of cumulative victimization on mental health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 106(3), 527–533. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302976.

Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2016). Developmental change in the effects of sexual partner and relationship characteristics on sexual risk behavior in young men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 20(6), 1284–1294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1046-6.

Nock, M. K., & Kazdin, A. E. (2002). Examination of affective, cognitive, and behavioral factors and suicide-related outcomes in children and young adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Abnormal Psychology, 31, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_07.

Nock, M. K., Borges, G., Bromet, E. J., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M., Beautrais, A., & Williams, D. (2008). Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. British Journal of Psychiatry, 192, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113.

O’Brien, K. H. M., Becker, S. J., Spirito, A., Simon, V., & Prinstein, M. J. (2014). Differentiating adolescent suicide attempters from ideators: examining the interaction between depression severity and alcohol use. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(1), 23 https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12050.

Oswald, R. F. (1999). Family and friendship relationships after young women come out as bisexual or lesbian. Journal of Homosexuality, 38(3), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v38n03_04.

Pisani, A. R., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Gunzler, D., Petrova, M., Goldston, D. B., Tu, X., & Wyman, P. A. (2012). Associations between suicidal high school students’ help-seeking and their attitudes and perceptions of social environment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(10), 1312–1324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9766-7.

Poteat, V. P., Sinclair, K. O., DiGiovanni, C. D., Koenig, B. W., & Russell, S. T. (2013). Gay–straight alliances are associated with student health: a multischool comparison of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(2), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00832.x.

Robinson, J. P., & Espelage, D. L. (2011). Inequities in educational and psychological outcomes between LGBTQ and straight students in middle and high school. Educational Researcher, 40(7), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X11422112.

Russell, S. T., Ryan, C., Toomey, R. B., Diaz, R. M., & Sanchez, J. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent school victimization: implications for young adult health and adjustment. Journal of School Health, 81(5), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00583.x.

Schlomer, G. L., Bauman, S., & Card, N. A. (2010). Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018082.

Schmeelk‐Cone, K., Pisani, A. R., Petrova, M., & Wyman, P. A. (2012). Three scales assessing high school students’ attitudes and perceived norms about seeking adult help for distress and suicide concerns. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 42(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00079.x.

Shneidman, E. S. (1993). Suicide as psychache: A clinical approach to self-destructive behavior. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson.

Szymanski, D. M., Kashubeck-West, S., & Meyer, J. (2008). Internalized heterosexism: a historical and theoretical overview. The Counseling Psychologist, 36(4), 510–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000007309488.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

Taliaferro, L. A., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2014). Risk and protective factors that distinguish adolescents who attempt suicide from those who only consider suicide in the past year. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12046.

U.S. Surgeon General. (2001). National strategy for suicide prevention: Goals and objectives for action. Rockville: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

Van Orden, K. A., Lynam, M. E., Hollar, D., & Joiner, Jr., T. E. (2006). Perceived burdensomeness as an indicator of suicidal symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30(4), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9057-2.

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Gordon, K. H., Bender, T. W., & Joiner, T. E. (2008). Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72.

Vijayakumar, L., Kumar, M. S., & Vijayakumar, V. (2011). Substance use and suicide. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 24(3), 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283459242.

Whitaker, K., Shapiro, V. B., & Shields, J. P. (2016). School-based protective factors related to suicide for lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(1), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.008.

Wyman, P. A. (2014). Developmental approach to prevent adolescent suicides: research pathways to effective upstream preventive interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3), S251–S256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.039.

Wyman, P. A., Brown, C. H., Inman, J., Cross, W., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Guo, J., & Pena, J. B. (2008). Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.104.

Wyman, P. A., Brown, C. H., LoMurray, M., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Petrova, M., Yu, Q., & Wang, W. (2010). An outcome evaluation of the Sources of Strength suicide prevention program delivered by adolescent peer leaders in high schools. American Journal of Public Health, 100(9), 1653–1661.

Ybarra, M. L., Mitchell, K. J., Kosciw, J. G., & Korchmaros, J. D. (2015). Understanding linkages between bullying and suicidal ideation in a national sample of LGB and heterosexual youth in the United States. Prevention Science, 16(3), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-014-0510-2.

Zaza, S., Kann, L., & Barrios, L. C. (2016). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: population estimate and prevalence of health behaviors. JAMA, 316(22), 2355–2356. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.11683.

Funding

Data in this manuscript were drawn from a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1 U01 CE002841) to Dorothy L. Espelage and Peter Wyman (Co-PIs).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. IRB approval was received from the University of Florida, the University of Rochester, the Colorado Department of Public Health, and Texas Tech University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hatchel, T., Ingram, K.M., Mintz, S. et al. Predictors of Suicidal Ideation and Attempts among LGBTQ Adolescents: The Roles of Help-seeking Beliefs, Peer Victimization, Depressive Symptoms, and Drug Use. J Child Fam Stud 28, 2443–2455 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01339-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01339-2