Abstract

Parents of children with developmental disabilities (DD) typically report higher levels of parental stress than parents of typically developing children. While the majority of the literature addresses child behavior problems as predictors of parental stress, research has shown that the relation is bi-directional. However, very little research has examined the effects of parental stress on child behavior problems and the possible parenting factors that may explain this relation. The current study utilized data from the Mindful Awareness for Parenting Stress (MAPS) study (N = 31; % male = 67.7, mean age = 3.5, SD = .96; 81% ethic minority), and examined positive parenting behaviors as mediators in the relation between parenting distress and child behavior. Results from a multiple mediation analysis indicated that Parental Distress had a significant direct effect on total Child Behavior Problems, b = 1.11, p < .05. Additionally, Quality of Mother's Assistance was a significant mediator in the relation between Parental Distress and Child Behavior Problems, ab = .482, 95% BCa 95% CI [.022, 2.33]. Neither Level of Involvement nor Mother's Supportive Presence significantly mediated the relation between Parental Distress and Child Behavior Problems, ps > .05. Findings suggest that improving the quality of the parent/child interaction may play a key role in the relation between parenting stress and child behavior problems. The current study could help to inform future parenting interventions by emphasizing the importance of targeting quality of parent assistance type parenting behaviors for improving child behavior outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parents of children with developmental disabilities (DD) consistently report higher levels of parental stress compared to parents of typically developing children (Baker et al. 2003; Webster et al. 2008). Research indicates that this stress is more a result of child problem behaviors rather than intellectual ability (Baker et al. 2005; Neece et al. 2012). While the majority of the literature addresses child behavior problems as predictors of parental stress, research has shown that the relation between child behavior problems and parental stress is bidirectional (Neece et al. 2012). However, very little research has looked at the effect of parental stress on child behavior problems and the possible parenting factors that explain this relation. It is likely that parental stress impacts parenting behavior, which subsequently contributes to child behavior problems (McIntyre 2008). It is also possible that parents who are less stressed exhibit more positive parenting behaviors (e.g. scaffolding, warmth, sensitivity), which ameliorate the development of child behavior problems that are common among children with DD.

Research has shown that parenting stress influences the parent-child relationship and parenting behavior (Guajardo et al. 2009). Parents with high levels of stress tend to perceive their child as more difficult and subsequently lack warmth and responsiveness in their parenting behaviors and interactions with their children and exhibit discipline that is either too relaxed or excessively involved (Crawford and Manassis 2001; Karrass et al. 2003). Additionally, parents that report high levels of parenting stress are typically less responsive, warm, and affectionate, and are more likely to use controlling and assertive parenting techniques compared to parents with lower levels of stress (McLoyd 1990). Children of parents that display these power assertive parenting techniques may not learn to solve problems independently and, as a result, are less likely to develop adequate self-regulation (Baumrind et al. 2010). Given that parents of children with DD typically experience higher levels of stress compared to parents of typically developing children, it is likely that parenting stress has an even greater effect on parenting behavior in parents of children with DD (Baker et al. 2003; Webster et al. 2008).

Positive parenting behavior in particular is important in predicting the well-being of children (Sanders 1999). Specifically, positive parenting behaviors have been associated with adaptive child adjustment (Siequeland et al. 1996), positive social development (Leidy et al. 2010), improved cognitive-language development (Landry et al. 2008), increased child empathy (Padilla-Walker and Christensen 2010), fewer externalizing behaviors (Eisenberg et al. 2005), and better emotional competence (Stack et al. 2010). Similar effects have been observed in families of children with DD where positive parenting behaviors have been associated with fewer externalizing behaviors (Glazemakers and Deboutte 2013), positive social skills development (Baker et al. 2007), and improved language development (Siller and Sigman 2002). In contrast, research has shown that a lack of a warm, supportive, and positive relationship with a parent, inconsistent discipline, insensitivity, and inadequate involvement increase the risk of behavior and emotional problems in children (Loeber and Farrington 1998). One positive parenting behavior consistently associated with positive child outcomes is the quality of the parent’s assistance, or the degree to which parents provide the support necessary to enable a child to attempt a task, giving the minimal but sufficient amount of assistance necessary to promote maximum autonomy (Dietrich et al. 2006; Hammond et al. 2012).

By providing appropriate assistance based on the child’s ability, parents transform tasks that are beyond the child’s ability into tasks the child can learn from and begin to complete autonomously, which allows parents to facilitate the child’s learning (Hammond and Carpendale 2015). Through the parent’s appropriate assistance, the child is able to learn more developmentally advanced tasks and independently solve more complex problems (Lowe et al. 2013). Among typically developing children, parenting with appropriate assistance that allows for maximum autonomy has been associated with improvements in child executive functioning (Hammond et al. 2012), prosocial behaviors such as helping or sharing (Pettygrove et al. 2013), verbal abilities (Landry et al. 2002), and academic performance (Dietrich et al. 2006). Parents of children with disabilities may find providing appropriate assistance and opportunities for autonomy more difficult, as it may be more challenging to determine their children’s role in an interaction and effectively encourage their participation (Ninio and Snow 1996). Specifically, more directive approaches to parenting are more common in parents of children with developmental disabilities (Abbeduto et al. 1999; Marfo 1992), and providing appropriate assistance and opportunities for maximum autonomy has been shown to be more predictive of social competence in children with intellectual disabilities than for typically developing children (Baker et al. 2007; Guralnick et al. 2008). Thus, it appears that providing appropriate assistance and opportunities for independent task completion is beneficial for children’s development in a number of domains and appears to be particularly helpful for children with developmental risk such as children with DD.

While quality of parent’s assistance has been associated with many positive child outcomes, parent involvement in a task also has positive implications for children. An appropriate amount of parent involvement in parent-child interactions is an integral part of the child’s development of social and adaptive skills, and understanding of appropriate behaviors (Power 2004). Parenting that is lenient and less involved has been associated with higher levels of child externalizing behaviors (Rinaldi and Howe 2012). Conversely, high levels of parenting involvement is characterized by unsolicited and overinvolved instruction (Rubin et al. 2009), which over time can deter the child from developing independent behaviors, problem solving abilities, and coping skills (Power 2004; Rubin et al. 2009). Previous research has found that parents of children with DD tend to be more involved and negative, and display fewer positive parenting behaviors, which may place their children at an even greater risk for behavior problems (Brown et al. 2011; McIntyre 2008). However, the majority of the research examining parental involvement has been conducted with typically developing (TD) children, and implications of overinvolved parenting evident in TD children may be different for children with DD who may benefit from more direct involvement, which may be more developmentally appropriate (Fenning et al. 2007). Therefore, it is important to examine the relation between parental involvement and child behavior in a sample of children with DD.

Supportive parenting provides an emotional climate that is encouraging of the child completing a task, regardless of the effectiveness of the parent’s attempt to get the child to carry out the task. This type of environment is characterized by a sensitive caregiver who is aware of the child’s needs and provides an emotional environment that is tailored to the child’s needs. Supportive and sensitive parenting has been consistently associated with higher social competence and language development in children (Barnett et al. 2012). Sensitive and supportive parenting may also strengthen the mother-child attachment, which improve child emotion regulation (ER) skills (Thompson 2006) and subsequent child behavior problems (Howse et al. 2003). These specific positive parenting behaviors are important to study in families of children with DD who are at increased risk for ER problems, behavior problems and ultimately psychopathology.

The current study sought to further understand the relation between parental stress and child behavior problems by exploring the role of positive parenting behaviors in this association. The following question was examined: Do specific parenting behaviors mediate the relation between parental distress and child behavior problems? We hypothesized that higher levels of parental distress would predict a greater number of child behavior problems and would be explained by specific parenting behaviors, including the quality of the mother’s assistance, the level of the mother’s involvement, and the mother’s supportive presence. Specifically, we predicted that higher levels of parenting stress would predict an increased quality of mother’s assistance, and lower mother sensitivity. We also predicted that lower parent stress would predict moderate levels of mother involvement. We hypothesized that an increased quality of mother’s assistance and higher mother sensitivity would predict fewer child behavior problems. Additionally, we predicted that a higher level of involvement would predict a greater number of child behavior problems.

Method

Participants

The current study involved 31 parents who participated in the Mindful Awareness for Parenting Stress (MAPS) Project, which included parents of children ages 2.5 to 5 years old with DD. Participants were primarily recruited through the Inland Empire Regional Center located in Southern California although some were recruited through the local newspaper, local elementary schools, and community disability groups. In California, practically all families of individuals with DD receive services from one of nine Regional Centers. Families who met the inclusion criteria were selected by the Regional Center’s computer databases and received a letter and brochure informing them of the study. Information about the study was also posted on a website which allowed interested parents to submit their information.

Criteria for inclusion in the study were: (1) Having a child ages 2.5 to 5 years, (2) child was determined by Regional Center (or by an independent assessment) to have a DD, (3) parent(s) reported more than 10 child behavior problems (the recommended cutoff score for determining risk of conduct problems) on the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Robinson et al. 1980), (4) the parent was not receiving any form of psychological or behavioral treatment at the time of referral (e.g., counseling, parent training, parent support group, etc.), (5) parent agreed to participate in the intervention, and (6) parent spoke and understood English. Exclusion criteria included parents of children with debilitating physical disabilities or severe intellectual impairments that prevented the child from participating in a parent-child interaction task that was a part of the larger laboratory assessment protocol (e.g., child is not ambulatory). In order to be included, parents must also have completed all baseline measures and attended the baseline assessment before the beginning of the first intervention session.

Of the ninety-five families that were screened for the study, 63 were determined to be eligible, and 46 parents completed the baseline assessment. The most common reason for lack of participation within eligible families was due to scheduling and availability. Within participating families, primary and secondary informants were identified at the baseline assessment. The primary informants were all mothers that participated in the laboratory assessments. Out of the 46 participants in the study, six were secondary informants and were excluded from all analyses in the current study, so as to not include children twice. Six of the parent–child interaction task videos were lost due to equipment malfunction, and three mothers did not provide complete data relevant to the current study. This left 31 mothers who provided complete data for the measures included in the study. There were no demographic differences between participants that turned in complete data vs. those who did not complete the measures relevant to this study.

In the combined sample (N = 31), 67.7% of the children were boys. Parents reported 29.0% of the children as Caucasian, 35.5% as Hispanic, 6.5% as Asian, 3.2% as African American, and 25.8 % as “Other.” The mean age of the children was 3.5 years with a standard deviation of .96. The majority of the participating parents were married (74.2%) and all were mothers. Families reported a range of annual income; 51.6% reported an annual income of more than $50,000 and incomes ranged from $0 to over $95,000. Parents completed an average of 14.71 years in school with a standard deviation of 2.94. Demographics of study participants are reported in Table 1.

Procedure

Interested parents contacted the MAPS project by phone, postcard, or submitting their information on the project website. Study personnel then conducted a phone screen to determine the eligibility of the parent or parents. If the parent met inclusion criteria, a laboratory baseline assessment was scheduled. Prior to the baseline assessment, parents were mailed a packet of questionnaires that were to be completed before arrival at the assessment.

The baseline assessment took place in the lab at Loma Linda University Psychology Department. At this assessment, parents were given an informed consent that was reviewed by study staff. After completing the informed consent and an interview to collect demographic information, each parent and child participated in a parent-child interaction task. Parents and children were asked to participate in three 5-minute long interaction tasks including a Child-led play task, a Parent-led play task, and a Clean-up task. For the current study, Observational Coding was conducted on the Clean-up task only, and all data in the current study were cross-sectional.

Measures

Demographic data

Demographic data were collected during an interview with the participating parent.

Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 1 ½–5

The CBCL 1 ½ to 5 was used to assess child behavior problems (CBCL; Achenbach 2000). The CBCL contains 99 items that are scored as “not true” (0), “somewhat or sometimes true” (1), or “very true or often true” (2). Prior to the initial assessment, parents completed the question. Each item represents a problem behavior, such as “acts too young for age” and “cries a lot.” For the current study, we used the Total Behavior Problems score at intake, which is a sum score of all items in the scale. Reliability for the Total Behavior Problems score in the current study was high (α = .94).

Parenting Stress Index—Short Form

The Parenting Stress Index—Short Form (PSI-SF) was used to assess parenting stress (Abidin 1995). The PSI-SF contains 36 items that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Agree” (1) to “Strongly Disagree” (5). For the current study, we used the Parental Distress subscale, which measures the extent to which the parent is experiencing stress in his or her role as a parent independent of child behavior problems. Reliability for the Parental Distress subscale with our sample was α = .83. Parents completed the PSI-SF prior to attending the intake assessment.

Clean-up task coding system

Observational coding was conducted using the Clean-Up Task Coding Manual Version 1.0 (Guisti et al. 1997), which was adapted from the Child Compliance/Mother Discipline Project Coding/Entry Manual and used in previous research (Kochanska et al. 2001; Kochanska and Aksan 1995). The manual was designed for use in contexts that provide opportunities for parental control behaviors with young children (Guisti et al. 1997), and emphasizes the assessment of maternal discipline styles and child compliance occurring throughout a parent-child directed clean up interaction. Global codes of maternal control are assigned to represent the entire cleanup interaction.

Global codes of maternal control

After the parent-child interaction was viewed twice by two individual coders, the overall interaction was assigned three distinct consensus codes (Quality of Mother Assistance, Mother Supportive Presence, Level of Involvement) representing different aspects of maternal control. The Quality of Mother Assistance code (ICC = .98) represents the degree to which a mother assists in nurturing the child’s interest and motivation in the cleanup task, while allowing the child maximum opportunity for autonomous behavior. Scores on this code range from 1 (totally intrusive, or ineffective and may frustrate the child; does not allow for autonomy) to 5 (mother provides clear, well-paced effective instruction that allows for autonomy; mother offers assistance or modeling according to the child’s needs). Mother Supportive Presence (ICC = .92) represents the degree to which the mother provides an emotional climate that is supportive of completing the cleanup task, regardless of the effectiveness of her intervention. Scores on this code range from 1 (mother is not supportive) to 5 (mother’s support is excellent in providing the child with a positive experience). The Level of Mother Involvement (ICC = 1.00) code is used to determine who was primarily responsible for completing the cleanup task. Scores on this code range from 1 (no mother involvement) to 4 (no effective child involvement/mother completes entire clean up task).

Data Analyses

Conceptually, we expected that the Level of Involvement variable would have a non-linear relation with both Parental Distress and Child Behavior Problems. Specifically, research has shown that higher parental stress has been associated with both high parent involvement (overinvolved parenting) and low parent involvement (lenient/underinvolved parenting) (Crawford and Manassis 2001; Karrass et al. 2003), as well as a greater number of child behavior problems (Power 2004; Rinaldi and Howe 2012). Scatter plots indicated a quadratic relation between Level of Involvement and Parent Distress and between Level of Involvement and Child Behavior Problems, such that moderate levels of Mother Involvement were associated with the lowest parent distress and the fewest child behavior problems. Before addressing our hypotheses, we squared the Level of Involvement variable in order to support a quadratic relation between Level of Involvement and both Parental Distress and Level of Involvement and Child Behavior Problems.

Prior to testing our multiple mediation model, demographic variables were correlated with both the IV and DV. The demographic variables analyzed were those that are listed in the demographic table below (Table 1). No demographic variables were found to significantly correlate with both the IV and the DV. Therefore, no demographic covariates were included in the model.

Before running our main analysis, we also tested for outliers, multicollinearity, and for the assumptions of regression. Bi-variate correlations were run, and correlational statistics are included in Table 2. A multiple linear regression was run and VIF and Tolerance values were obtained in order to test for multicollinearity; DFBetas, Leverage, and Studentized Deleted Residuals were obtained and evaluated to test for the leverage, discrepancy, and influence of outliers. Multicollinearity was considered a concern if values were outside of the following ranges: VIF > 10 and Tolerance < .1. Cases were considered outliers if values for DFBetas, Leverage and Studentized Deleted Residuals were all outside the following ranges: DFBetas ± 1, Leverage < .48, and Studentized Deleted Residuals ± 2.06 (Cohen et al. 2003). We found no multicollinearity concerns, no significant outliers, and our data did not violate any of the assumptions of regression.

A multiple mediation model was used to test Parental Distress as a predictor of Child Behavior Problems through the effects of positive parenting behaviors, specifically the Quality of the Mother’s Assistance, the Level of the Mother’s Involvement, and the Mother’s Supportive Presence. Frequently, the causal steps strategy or product-of-coefficients strategy are used to test for mediation. However, the causal steps strategy, which was described by Baron and Kenny (1986), has low power. Furthermore, the product-of-coefficients strategy relies on the assumption that the sampling distribution of the mediated effect is normal, which is not always the case (Hayes 2009). Alternatively, bootstrapping methods can be used to test the significance of the indirect effect. Bootstrapping does not assume that the sampling distribution of the indirect effect is normal, and tends to have lower type I error and higher power than other mediation strategies. Furthermore, we used a multiple mediation model for our analyses. Multiple mediation allows the calculation of the total indirect effect of multiple mediators and the individual indirect effect of each mediator, the comparison of the magnitudes of the two mediators, and limits parameter bias from omitted variables (Preacher and Hayes 2008).

The present study was conducted in SPSS 20 (IBM 2012) using the multiple mediation macro called “Indirect” (Preacher and Hayes 2008). We evaluated three possible mediators (Mother’s Involvement, Supportive Presence, and Quality of the Mother’s Assistance) of the relation between parental distress and child behavior problems using a bootstrapping approach. The current study was based on 5000 randomly drawn bootstrap samples to calculate estimates of effect, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals. The total indirect effect, individual effects for each mediator (ab), and a pairwise comparison of the two mediators was evaluated based on the bias corrected and accelerated CIs (BCa CI). The bias corrected and accelerated CI was used as it is considered to be the most accurate (Preacher and Hayes 2008). The p-value was inferred to be <.05 when the CI did not contain zero.

Results

The majority of parents in the current study endorsed clinical levels (>85 percentile) of parenting stress (77.4%; M = 38.03, SD = 8.78), and the average number of child behavior problems reported was high (M = 75.10, SD = 26.46). Specifically, 19.3% of parents reported a Borderline Clinical (60–70) number of behavior problems, and 51.6% of parents reported a Clinically Significant (>70) number of behavior problems.

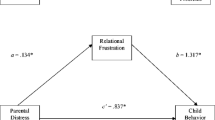

Results of a multiple mediation analysis indicated that Parental Distress had a significant direct effect on total Child Behavior Problems, b = 1.11, p < .05. Specifically, as Parental Distress increased by one point, Child Behavior Problems increased by 1.11 points. Quality of Mother’s Assistance significantly mediated the relation between Parental Distress and Child Behavior Problems, such that a one-point increase in Parental Distress was associated with a .48-point increase in Child Behavior Problems through the effects of Quality of Mother’s Assistance, BaC 95% CI [.022, 2.33]. Level of Involvement and Mother’s Supportive Presence were not significant mediators in the relation between Parental Distress and Child Behavior Problems, p > .05. While Parental Distress did not uniquely predict any of the positive parenting factors (ps > .05), Quality of Mother’s Assistance individually and significantly predicted Child Behavior Problems (b 1 = −10.90, p < .05). Neither Level of Involvement nor Mother’s Supportive Presence significantly predicted Child Behavior Problems, ps > .05. Results from a multiple mediation analysis testing Quality of Mother’s Assistance, Level of Involvement, and Mother’s Supportive Presence as mediators in the relation between Parental Distress and Child Behavior Problems are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 1.

Given previous research addressing the relation between child behavior problems and parental stress, it is also possible that parenting factors mediate this relation, which is opposite of the original proposed model. In order to test this relation, we ran an additional mediation model with Quality of Mother’s Assistance, Level of Involvement, and Mother’s Supportive Presence as mediators in the relation between child behavior problems and parental stress. None of the parenting factors were significant mediators, ps > .05.

Discussion

While the relation between parenting stress and child behavior has been shown to be bidirectional (Neece et al. 2012), the majority of research has examined the effects that child behavior has on parental distress. This study helped to further our understanding of the relation between parental distress and child behavior problems and the mechanisms that may explain this relation. We examined specific positive parenting behaviors as mediators of the relation between Parenting Distress and Child Behavior Problems. Our hypotheses predicted that all three positive parenting behaviors (Quality of Mother’s Assistance, Mother’s Level of Involvement, and Mother’s Supportive Presence) would significantly explain the relation between parental distress and child behavior problems, which was partially supported. Quality of Mother’s Assistance significantly explained the relation between Parental Distress and Child Behavior Problems; however, neither Level of Involvement nor Mother’s Supportive Presence significantly mediated the relation between Parental Distress and Child Behavior problems.

The current study highlights the relation between parental stress and child behavior problems and the importance of parenting behaviors. Specifically, findings indicated that the relation between parental stress and child behavior problems was explained by quality of mother’s assistance. While we cannot infer causality given the cross-sectional nature of our data, these findings highlight the need for additional research with longitudinal data in order to better understand the direction of effects in this relation. There are numerous studies that support the relation between quality of mother’s assistance type behaviors and child behavior outcomes (Baker et al. 2007; Lowe et al. 2013). However, the impact of parenting stress on parenting behavior is far less understood, and the mechanisms by which parenting stress impacts parenting behavior are unclear. Likely, there are many factors that affect how stress impacts parenting behavior, such as parents’ perception of the child’s difficult behaviors, perception of the impact that parenting has on the child’s behavior, or the parent’s own mental health. Several studies have shown that parents with higher levels of stress that also perceive their children to be “difficult” tend to exhibit either under involved parenting behaviors or overinvolved parenting behaviors and lack warmth in their interactions with their children (Karrass et al. 2003). Additionally, parental stress has been associated with increased parental psychopathology, which could affect child outcomes. Specifically, higher parental stress has been linked to higher levels of parental depression (Murray et al. 1996), and parental depression has been negatively associated with parenting behavior (Downey and Coyne 1990), which could affect child behavior. In order to optimize child outcomes, we need further research evaluating factors that may affect the relation between parenting stress and parenting behavior in order to better understand which areas to address in interventions.

Consistent with prior research in TD populations, our study emphasized the importance of the relation between quality of mother’s assistance and child behavior problems for children with DD. A wide range of positive child outcomes are associated with parenting behaviors similar to quality of parent assistance in the TD literature including improvements in child executive functioning (Hammond et al. 2012), academic performance throughout the school years (Dietrich et al. 2006), and cognition (Landry et al. 2001). Understanding the relation between parenting behavior and child behavior in children with DD is especially important given that parenting factors may be more even more influential on child behavior when the child is already at risk or vulnerable (Denham et al. 2000). In a study by Denham et al. (2000), children with higher defiant behavior problems at the onset of the study showed the strongest relation between externalizing behaviors and parenting. While children with DD are at an already increased risk for behavior problems, a lack of appropriate parent assistance while allowing for autonomy may have an even greater negative effect on behavior outcomes in these children in comparison to TD children. Understanding the relation between the quality of parent assistance and child behavior in children with DD could help to more effectively target specific parenting behaviors in future interventions. Parenting behaviors, such as the quality of mother’s assistance, have been found to be important parent factors for child behavior outcomes; however, accurately measuring parent behaviors across all populations is difficult.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Assessing the quality of mother’s assistance is especially challenging given the overlapping nature of the components that make up this construct, which is a limitation in the current study. While neither Level of Involvement nor Mother’s Supportive Presence were found to individually explain the relation between Parental Distress and Child Behavior problems, aspects of these constructs are evident in the Quality of Mother’s Assistance construct. Quality of Mother’s Assistance involves the parent providing a social structure necessary to enable a child to attempt a task and only the amount of assistance necessary for the child to complete the task (Hammond and Carpendale 2015). Conceptually, a mother with high levels of Quality of Mother’s Assistance must incorporate an appropriate level of involvement for the child’s developmental needs that are supportive of the child’s learning and needs. While each of these parenting behaviors are operationalized in the coding system as individual constructs, high Quality of Mother’s Assistance cannot occur without both adequate parent involvement and support in the interaction. Additionally, child developmental level is important to consider when measuring parenting behavior. While the coding system does take into account the child’s level of development, the current study did not have sufficient measures of child functioning level. An accurate measure of child functioning level could help to determine if this variable would be an appropriate covariate in our analyses. Measuring parenting behaviors is also difficult due to the way in which child behavior affects parenting behavior and vice versa.

The relation between parenting behaviors and child behavior problems is complex. While addressing these relations with observational parent behavior data and multiple mediators was a strength of the study, accurately measuring parenting behavior is difficult and comes with some limitations. Parenting behaviors are often measured independent of child behavior. However, in reality, parenting behavior is usually contingent on or in response to child behavior. Specifically, the way in which a parent interacts with the child affects how the child responds, and the child’s behavior subsequently affects the parent’s parenting behavior. Unfortunately, the field has not developed a useful way to capture these contingent dyadic interactions. However, it will only be by attending to the complexity of these developmental interactions that we will accurately be able to study the reciprocal relation between parent and child behavior.

An additional limitation regarding variables in the current study is that parenting stress and child behavior are both obtained from a single reporter at one time point. It is possible that differences in parent report of stress or child behavior problems were influenced by parent perception. Specifically, an increase in child behavior problems may influence parent stress levels. Similarly, higher levels of stress may affect parent perception of child behavior problems. A longitudinal study design would help to address this concern. In addition, there is a need for future studies to have multiple reporters and multiple measures of these variables.

Given that cross-sectional data were used for the current study and that mediation consists of causal processes that occur over time, there are inherent biases that are evident. While we did run the mediational model in the both directions, we did not find any significant indirect effects with child behavior as a predictor of parenting stress, which was the alternative direction of effect to our proposed model. However, we cannot definitively determine the direction of effect or infer causation. Thus, future studies should reexamine our mediation model using longitudinal data. Nevertheless, given the limited research addressing how parental stress affects child behavior, the current study provides a foundation for future longitudinal research.

Sample size is also a statistical concern for this study. Bootstrapping, was used in the current study; this method tends to have higher power and lower type one error and is more robust in cases with smaller sample sizes than other mediation strategies (Preacher and Hayes 2008). Given our small sample size, the significant mediation effect is robust. However, it is possible that there is Type II error and the two non-significant findings would be significant with a larger sample. A larger sample size would provide more certainty in our results.

While the current study provides insight into the relation between parental distress and child behavior problems, it would be advantageous for future researchers to examine additional factors that may affect this relation. While Mother’s Involvement and Mother’s Sensitivity were not significant mediators in the current study, the relation between Parental Distress and Child Behavior Problems may be mediated by a variety of other parent factors shown to be related to Parental Distress. Future research could examine additional potential mediators or other factors such as parent mental health or parent perception of child behavior that affect these processes in longitudinal studies with larger samples using multi-level linear modeling or structural equation modeling. Additionally, the current study did not consider possible moderators of the relation between parental distress and child behavior. Research supports evidence of the relation between socio economic status (SES) and parental distress (Leigh and Milgrom 2008), as well as SES and parenting behavior (McLoyd 1990). Low-income families tend to place greater value on child autonomy and assume that they have less impact on child behavior. In turn, poverty has been associated with lower levels of parental affective expression, sensitivity, and more frequent power assertive parenting behaviors (McLloyd and Wilson 1990; Sameroff et al. 1982). SES and other family factors (i.e., single parent households) may moderate the mediation effects in the relation between parental distress and child behavior. By examining these additional moderating and mediating factors, future models with longitudinal data may give us a better understanding of the factors that affect the relation between parental distress and child behavior problems.

Results of the current study help to further explain the relation between parental stress and child behavior problems and provide a foundation for future longitudinal research. Improving the quality of the parent/child interaction may play a key role in the relation between parenting stress and child behavior problems. The current study could help to inform future parenting interventions by emphasizing the importance of targeting quality of parental assistance type parenting behaviors for improving child behavior outcomes.

References

Abbeduto, L., Weissman, M. D., & Short-Meyerson, K. (1999). Parental scaffolding of the discourse of children and adolescents with intellectual disability: The case of, referential expressions. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 43, 540–557. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.1999.00249.x.

Abidin, R. (1995). The Parenting Stress Index (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Achenbach T. M. (2000). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist 1 ½-5. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Elizabeth A. Robinson, Sheila M. Eyberg, A. William Ross, (2009). The standardization of an inventory of child conduct problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 9 (1), 22-28

Baker, B. L., Blacher, J., & Olsson, M. B. (2005). Preschool children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems, parents’ optimism, and well-being. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 575–590.

Baker, B. L., McIntyre, L. L., Blacher, J., Crnic, K., Edelbrock, C., & Low, C. (2003). Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47, 217–230.

Baker, J. R., Fenning, R. M., Crnic, K. A., Baker, B. L., & Blacher, J. (2007). Prediction of social skills in 6-year-old children with and without developmental delays: Contributions of early regulation and maternal scaffolding. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 112, 375–391.

Barnett, M. A., Gustafsson, H., Deng, M., Mills-Koonce, W. R., & Cox, M. (2012). Bidirectional associations among sensitive parenting, language development, and social competence. Infant and Child Development, 27, 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1237430.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Baumrind, D., Larzelere, R. E., & Owens, E. B. (2010). Effects of preschool parents’ power assertive patterns and practices on adolescent development. Parenting, science and practice, 10, 157–201.

Brown, M. A., McIntyre, L. L., Crnic, K. A., Baker, B. L., & Blacher, J. (2011). Preschool children with and without developmental delay: Risk, parenting, and child demandingness. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 4, 206–226.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences 3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Crawford, A., & Manassis, K. (2001). Familial predictors of treatment outcome in childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1182–1189.

Denham, S. A., Workman, E., Cole, P. M., Weissbrod, C., Kendziora, K. T., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (2000). Prediction of externalizing behavior problems from early to middle childhood: The role of parental socialization and emotion expression. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 23–45.

Dietrich, S. E., Assel, M. A., Swank, P., Smith, K. E., & Landry, S. H. (2006). The impact of early maternal verbal scaffolding and child language abilities on later decoding and reading comprehension skills. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 481–494.

Downey, G., & Coyne, J. C. (1990). Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 50–76.

Eisenberg, N., Zhou, Q., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Fabes, R. A., & Liew, J. (2005). Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development, 76, 1055–1071.

Fenning, R. M., Baker, J. K., Baker, B. L., & Crnic, K. A. (2007). Parenting children with borderline intellectual functioning: A unique risk population. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 112, 107–121.

Glazemakers, I., & Deboutte, D. (2013). Modifying the ‘Positive Parenting Program’ for parents with intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research, 57, 616–626.

Guajardo, N. R., Snyder, G., & Peterson, R. (2009). Relationships among parenting practices, parental stress, child behaviour, and children’s social- cognitive development. Infant and Child Development, 18, 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.

Guralnick, M. J., Neville, B., Hammond, M. A., & Connor, R. T. (2008). Mother’s social communicative adjustments to young children with mild developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 113, 1–18.

Guisti, L., Mirsky, E., Dickenstein, S., & Seifer, R. (1997). Clean-Up Task Coding Manual Providence Family Study Version 1.

Hammond, S. I., & Carpendale, J. I. M. (2015). Helping children help: The relation between maternal scaffolding and children’s early help. Social Development, 24, 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12104.

Hammond, S. I., Müller, U., Carpendale, J. I. M., Bibok, M. B., & Liebermann-Finestone, D. P. (2012). The effects of parental scaffolding on preschoolers’ executive function. Developmental Psychology, 48, 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025519.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420.

Howse, R., Calkins, S. D., Anastopoulos, A., Keane, S., & Shelton, T. (2003). Regulatory Contributors to Children’s Kindergarten Achievement. Early Education and Development, 14, 101–119.

IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Karrass, J., VanDeventer, M., & Braungart-Riker, J. (2003). Predicting shared parent–child book reading in infancy. Journal of Family Psychology 17, 134–146.

Kochanska, G., & Aksan, N. (1995). Mother-child mutually positive affect, the quality of child compliance to requests and prohibitions, and maternal control as correlates of early internalization. Child Development, 66, 236–254.

Kochanska, G., Coy, K. C., & Murray, K. T. (2001). The development of self-regulation in the first four years of life. Child Development, 72, 1091–1111.

Landry, S. H., Miller-Loncar, C. L., Smith, K. E., & Swank, P. R. (2002). The role of early parenting in children’s development of executive processes. Developmental Neuropsychology, 21, 15–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326942DN2101_2.

Landry, S. L., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R., Assel, M. A., & Vellet, S. (2001). Does early responsive parenting have a special importance for children’s development or is consistency across early childhood necessary? Developmental Psychology, 37, 387–403.

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R., & Guttentag, C. (2008). A responsive parenting intervention: The optimal timing across early childhood for impacting maternal behaviors and child outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1335–1353.

Leidy, M., Guerra, N., & Toro, R. (2010). Positive parenting, family cohesion, and child social competence among immigrant Latino families. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 252–260.

Leigh, B., & Milgrom, J. (2008). Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression, and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-8-24.

Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. P. (1998). Never too early, never too late: Risk factors and successful interventions for serious and violent juvenile offenders. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention, 7(1), 7–30.

Lowe, J. R., Erickson, S. J., MacLean, P., Schrader, R., & Fuller, J. (2013). Association of maternal scaffolding to maternal education and cognition in toddlers born preterm and full term. Acta Paediatrica, 102(1), 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12037.

Marfo, K. (1992). Correlates of maternal directiveness with children who are developmentally delayed. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 62, 219–233.

McIntyre, L. L. (2008). Parent training for young children with developmental disabilities: Randomized controlled trial. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 113, 356–368. https://doi.org/10.1352/2008.113.

McLoyd, V. (1990). The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting and socioemotional development. Child Development, 61, 311–346.

McLloyd, V. C., & Wilson, L. (1990). Maternal behavior, social support, and economic conditions as predictors of distress in children. In V. C. McLloyd & C. A. Flanagan (Eds.), Economic stress: Effects on family life and child development (pp. 49-69). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Murray, L., Stanley, C., Hooper, R., King, F., & Fiori-Cowley, A. (1996). The role of infant factors in postnatal depression and mother-infant interactions. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 38, 109–119.

Neece, C. L., Green, S. A., & Baker, B. L. (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117, 48–66.

Ninio, A., & Snow, D. E. (1996). Pragmatic Development. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Christensen, K. J. (2010). Empathy and self-regulation as mediators between parenting and adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends, and family. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 545–551.

Pettygrove, D. M., Hammond, S. I., Karahuta, E. L., Waugh, W. E., & Brownell, C. A. (2013). From cleaning up to helping out: Parental socialization and children’s early prosocial behavior. Infant Behavior and Development, 36, 843–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.09.005.

Power, T. G. (2004). Stress and coping in childhood: The parents’ role. Parenting, 4, 271–317.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Rinaldi, C. M., & Howe, N. (2012). Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and associations with toddlers’ externalizing, internalizing, and adaptive behaviors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27, 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.08.001.

Robinson, E. A., Eyberg, S. M., & Ross, A. W. (1980). The standardization of an inventory of child conduct problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 9, 22–29.

Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R. J., & Bowker, J. C. (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 141–171. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642.

Sanders, M. R. (1999). Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2, 71–90.

Siequeland, L., Kendall, P. C., & Steinberg, L. (1996). Anxiety in children: Perceived family environments and observed family interaction. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 225–237.

Siller, M., & Sigman, M. (2002). The behaviors of parents of children with autism predict the subsequent development of their children’s communication. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32, 77–89.

Sameroff, A. J., Seifer, R., & Zax, M. (1982). Early development of children at risk for emotional disorder. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stack, D. M., Serbin, L. A., Enns, L. N., Ruttle, P. L., & Barrieau, L. (2010). Parental effects on children’s emotional development over time and across generations. Infants and Young Children, 23, 52–69.

Thompson, R. A. (2006). The development of the person: Social understanding, relationships, conscience, self. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, N. Eisenberg, W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 24–98). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Webster, R. I., Majnemer, A., Platt, R. W., & Shevell, M. I. (2008). Child health and parental stress in school-age children with a preschool diagnosis of developmental delay. Journal of Child Neurology, 23, 32–38.

Author Contributions

C.S. designed and conceptualized the current study, coded and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. C.N. PI for the larger study; obtained funding and oversaw all elements of the larger study; provided feedback on the design, writing, and interpretation of the data; and contributed edits and revisions of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was supported by a GRASP (Grants for Research and School Partnerships Program) grant funded by Loma Linda University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanner, C.M., Neece, C.L. Parental Distress and Child Behavior Problems: Parenting Behaviors as Mediators. J Child Fam Stud 27, 591–601 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0884-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0884-4