Abstract

Little is known about the link between child abuse and health risk behaviors among Chinese college students. This cross-sectional study examined the prevalence of child abuse and its relations with individual and clusters of health risk behaviors among Chinese college students. A total of 507 students participated in this survey. The prevalence of child abuse from the highest to the lowest was emotional neglect (53.9%), physical neglect (49.0%), emotional abuse (21.8%), physical abuse (18.3%), and sexual abuse (18.1%), respectively. Males were more likely to report child abuse than females (p < 0.01). For males, emotional abuse was associated with internet addiction [OR = 2.28; 95%CI (1.00, 5.20)] and suicidal behavior [OR = 12.47, 95%CI (2.61, 59.54)]; while sexual abuse was associated with internet addiction [OR = 2.30, 95%CI (1.14, 4.66)]. For females, emotional abuse was significantly associated with increased risks for self-harm behavior [OR = 15.03, 95%CI (3.59, 63.07)] and suicidal behavior [OR = 5.16, 95%CI (1.63, 16.40)]. Physical abuse was related to risks for internet addiction [OR = 2.50, 95%CI (1.03, 6.04)] significantly. Two-step cluster analysis showed that participants in clusters with more health risk behaviors reported higher scores of child abuse. These findings suggest that child abuse was associated with both individual and clustering of health risk behaviors among Chinese college students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Child abuse is a major public health issue worldwide. The main types of child abuse include sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect (Bernstein et al. 2003). A recent meta-analysis of 55 studies from 24 countries showed that the prevalence of child sexual abuse ranged from 8 to 31% for girls and 3 to 17% for boys (Barth et al. 2013). Two other comprehensive meta-analyses showed that the prevalence of physical abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect were 17.7, 16.3, and 18.4%, respectively (Stoltenborgh et al. 2013a, b).

Adverse childhood experiences such as abuse can cause changes in brain structure and function and stress–responsive neurobiological systems, which in turn can lead to negative health outcomes and behaviors (Anda et al. 2006). Existing research shows that child abuse has long-term negative behavioral and psychological consequences on adolescent and adulthood. Kristman-Valente et al. found that child abuse (physical and sexual abuse) before aged 18 years was risk factors of adolescent smoking, which predicted smoking frequency in adulthood (Kristman-Valente et al. 2013). Two other studies showed that physical and sexual abuse history before aged 18 years among non-Asian women were significantly associated with sexual risk behaviors between 18 and 40 years old (Littleton et al. 2007; Roemmele and Messman-Moore 2011). A meta-analysis of 22 studies among Chinese subjects found child physical abuse before and at the age of 18 years was significantly associated with mental disorders (Lp et al. 2016). Another study on child sexual abuse among Chinese female adolescents aged between 17 and 19 years found that sexual abuse was associated with higher rates of mental health and behavioral problems, including depression, suicidal thinking and planning, alcohol use, smoking and having sexual intercourse (Chen et al. 2006). However, a key limitation of these studies is that only a few have assessed the impact of other types of child abuse, including emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. One study showed that exposures to emotional abuse and emotional neglect in childhood could affect brain development, and were important predictors of depression and suicidal ideation in both males and females (Anda et al. 2006). Furthermore, most previous studies only examined the impact of child abuse on individual health risk behavior. However, health risk behaviors may co-occur instead of acting independently (Busch et al. 2013; de Bruijn and van den Putte 2009), Therefore, there is a need to explore the relationships between various types of child abuse with clusters of health risk behaviors.

Existing research has shown that college students are at a critical transitional period when they could easily establish health risk behaviors (i.e., cigarette smoking, binge drinking, self-harm behavior, suicidal behavior, risky sexual behavior, and internet addiction) (Steptoe et al. 2002; Yang et al. 2016; Ye et al. 2015; Xu and Chen 2016), and these behaviors may have adverse health consequences in their later lives, including increased risks for chronic disease and cognitive impairment (Pelletier et al. 2016; Thayanukulvat and Harding 2015). Furthermore, the timing of abuse and the accumulation of adverse childhood experiences will impact later health status (Felitti et al. 1998). Given that studies among Chinese college students are limited, we, therefore, examined the relationship between child abuse and clusters of health risk behaviors among Chinese college students. Since males and females reported differing levels of adverse experiences and risk behaviors (Kristman-Valente et al. 2013), we explored whether the relations would be different based on gender.

Method

Participants

Year 1 college students were recruited via a multistage sampling method from Wuhan, China. Of the 600 approached students, 547 students (240 males and 307 females) aged between 18 and 24 years old (M = 20.3, SD = 1.1) were included in this study.

Procedure

This cross-sectional study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Wuhan University. At the first stage of the sampling, three colleges were selected randomly in Wuhan city. Second, one school in year 1 was selected from each college using a simple random sampling method. Third, two classes from each school were invited to participate in the study. Participants with a written informed consent completed a self-administered, confidential questionnaire in a classroom setting in the absence of teachers. The research staffs collected the questionnaires immediately after completion.

Measures

Demographic variables

Relevant basic demographic variables included participants’ age, gender, height, weight, school, and maternal education level [low (≤6 years), medium (7–12 years), or high (≥13 years)] (Canan et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2016).

Health risk behaviors

This survey investigated six health risk behaviors: internet addiction, self-harm behavior, suicidal behavior, current smoking, binge drinking, and risky sexual behavior. Items were adapted from Youth Behavior Survey Questionnaire (YRBS) developed by the CDC in the USA (Brener et al. 2002) and Young’s Internet Addiction Test (Young 2009). The questionnaires have been translated into Chinese and showed good validation in previous studies (Cao and Zhang 2010; Chen et al. 2004).

Internet addiction

The Young’s Internet Addiction Test was utilized to assess internet addiction. The scale consisted of 20 items with 5 response choices for each item scored from 1 to 5 (e.g., do you stay online longer than originally intendedly?). Participants with a total score higher than 50 were identified as “internet addiction” (Young 2009). The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.91 in the Chinese version (Cao and Zhang 2010).

Self-harm behavior

Participants were asked to report the frequency of hurting themselves deliberately (How often did you hurt yourself deliberately during the past 12 months, for example, by cutting yourself?) There were two response categories: “none” and “once or more”. The respondents who reported any self-harm behaviors were considered as having self-harm behavior (Stallard et al. 2013).

Suicidal behavior

Respondents were asked whether they had ever thought about or attempted at killing themselves in the past 12 months. If yes, they were classified as “suicidal behavior group” (Wan et al. 2012).

Current smoking

The behavior of current smoking was assessed by asking the number of days the respondents smoked a cigarette during the past 30 days. Respondents who reported smoking on one or more days in the previous 30 days were considered as “current smoking” (Fettes and Aarons 2011).

Binge drinking

Participants were asked to report number of days having five or more drinks in a row in the past 30 days. The response options included “none”, “1–2 days”, “3–5 days”, “6–9 days”, “10–19 days”, and “≥20 days”. For data analysis purpose, the responses were coded as “none = 0” and “once or more = 1” (Patrick et al. 2013). Those who reported any days were classified as binge drinking.

Risky sexual behavior

Risky sexual behavior was assessed by two items. Respondents were first asked to report whether they had any sexual intercourse in the past 30 days. Then, they were asked by a following question that if there was a condom use (e.g., Have you had sex with a condom?). If the answer was “yes” for the first question and “no” for the latter one, they were considered as “having risky sexual behavior” (Yang et al. 2016).

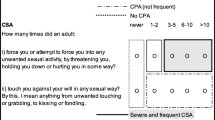

Child abuse

Experiences of child abuse occurred before aged 18 years were measured by using Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form (CTQ-SF), a well-validated retrospective self-report inventory (Bernstein et al. 2003). In this 28-item questionnaire, five dimensions of child abuse and neglect were identified including emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Strong internal consistency and test-rested reliability have been demonstrated with both English CTQ-SF (Bernstein and Fink 1994) and Chinese version (Zhao et al. 2005) for all subscales. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never true”) to 5 (“very often true”) and item scores were summed to quantify the severity of child abuse ranging from 25 to 100. The Cut-off scores identifying respondents from low to severe exposure for each subscale were: emotional abuse ≥ 9, physical abuse ≥ 8, sexual abuse ≥ 6, emotional neglect ≥ 10, and physical neglect ≥ 8 (Li et al. 2014). These cut-off scores have showed good validation in Chinese samples.

Data Analyses

SPSS statistical package (version 19.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to conduct data analysis. Of a total 600 participants, we excluded 93 questionnaires due to their age younger than 18 years old or with substantial missing data (>10% of all data). Otherwise, the missing data were handled in two ways: the missing value was recoded as a dummy variable for categorical variables; and for continuous variable, it was replaced by the mean value. First, the frequency distribution of demographic characteristics and child abuse pattern were described by using bivariate analyses. Chi-square test (for categorical variables) and t-test (for continuous variables) were performed to examine gender difference. Second, after preliminary analysis, we found significant difference between male and female participants. In the following analysis, data analyses were conducted in males and females respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to explore the relationships between five types of child abuse and individual health risk behaviors, after adjusting for demographic variables (age, body mass index (BMI), school, and maternal education). All five child abuse variables were included in a single model to predict each health risk behavior. The odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated in each regression model. Third, a two-step cluster analysis was conducted to identify groups of participants with similar health risk behaviors. The associations between child abuse and health risk behavior clusters were examined by using multivariate covariance analyses. Last, we conducted logistic regression analysis to explore the relationship between number of categories of child abuse and the clusters of health risk behaviors. The numbers of categories of child abuse experiences were included in a single model to predict if participants were in the unhealthy cluster identified in the last step.

Results

The basic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1. Of a total of 547 participants, 240 (43.9%) were males with an average age of 20.6 (SD = 1.2) and 307 (56.1%) females with an average age of 20.1 (SD = 1.1). Compared with female students, male students had a higher BMI (21.3 vs. 19.5, p < 0.001). No significant difference was observed in terms of maternal education between males and females. The highest and lowest child abuse symptoms reported in the study were emotional abuse (53.9%) and sexual abuse (18.1%), respectively. Male participants were more likely to report five types of child abuse than females (p < 0.01). Internet addiction was the most frequent health risky behavior among males (42.5%) and females (32.6%). The least frequent health risky behavior reported in this study was self-harm behavior in males (6.0%) and current smoking in females (0.3%), respectively. Male participants were significantly more likely to involve in internet addiction, current smoking, binge drinking, and risky sexual behavior than females (p < 0.01).

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, male students who were abused emotionally in childhood had significantly increased risks for both internet addiction [OR = 2.28, 95%CI (1.00, 5.20)] and suicidal behavior [OR = 12.47, 95%CI (2.61, 59.54)] in college. Childhood sexual abuse was significantly associated with higher rates of internet addiction [OR = 2.30, 95%CI (1.14, 4.66)]. In female students, emotional abuse was linked with increased risks for self-harm behavior [OR = 15.03, 95%CI (3.59, 63.07)] and suicidal behavior [OR = 5.16, 95%CI (1.63, 16.40)] in college, while physical abuse was associated with higher rates of internet addiction [OR = 2.50, 95%CI (1.03, 6.04)].

Characteristics of two different health risk behavior clusters are shown in Table 4. Male students in the unhealthy cluster showed significantly higher rates of five health risk behaviors (except for internet addiction) than those in the healthy cluster, and they were also more likely to have higher scores on three types of child abuse (emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and physical neglect) than the healthy cluster. Compared with those in the healthy cluster, female participants in the unhealthy cluster showed significantly higher rates of five health risk behaviors (except for current smoking) and significantly higher scores for five types of child abuse.

Table 5 shows the prevalence of co-occurrence of child abuse and its association with health risk behavior clusters. Male students who experienced three or more types of child abuse were three to five times more likely to engage in the unhealthy cluster than those without child abuse experiences. Female students with three or more types of child abuse experiences were about three to seventeen times more likely to end up in the unhealthy cluster.

Discussion

The current study is unique in that it reports the relation between child abuse and health risk behaviors clusters among Chinese college students. We show significantly positive associations between child abuse and health risk behaviors both individually and in cluster. Specifically, emotional abuse was associated with increased risks of internet addiction and suicidal behavior in males; for females, they were more likely to report suicidal and self-harm behavior with a history of emotional abuse. The association between sexual abuse and increased risks of internet addiction in males was not observed in females, while females who reported physical abuse were more likely to be involved in internet addiction. These findings contribute to a further understanding of child abuse and its impact on health behaviors among young adults.

Overall the prevalence of child abuse in this study is consistent with several previous studies conducted in mainland China, but higher than those in Hong Kong and Taiwan. For instance, the prevalence of sexual abuse in our study is similar to the study among 683 adolescents in mainland China by Lin et al. (2011), but is higher than 5.15% reported in another study in Taipei (Zhu et al. 2015) and 6% among 2147 Hong Kong college students (Tang 2002). Compared to international studies, the results are mixed. Lower prevalence of emotional abuse and higher prevalence of physical neglect were observed in our study when in comparison with the pooled estimates among Vietnamese college students (Tran et al. 2015), while emotional and physical neglect rates in the current study were higher than those in another international research (Stoltenborgh et al. 2013a, b). Several factors may contribute to the inconsistent findings: First, the understanding of child abuse may be different under diverse cultural backgrounds in different regions. Although mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are all influenced by traditional Confucian culture which emphasizes the virginity of female before marriage and parental authority, the extent of adherence to Confucius culture is discrepant due to different social systems and cultural values developed in the last few decades. Second, different research methodologies may lead to the inconsistence in these results, such as sampling method, scale, and cut-off points. Therefore, further studies are needed to explore the factors leading to these discrepancies across studies.

The current study shows that males reported significantly higher prevalence of child abuse than females. Gender difference in child abuse has also been observed in previous studies (Kristman-Valente et al. 2013; Lin et al. 2011). Several plausible reasons may explain for this phenomenon. First, gender stereotyping still exists in many Chinese families, and it requires that boys should play more important social roles and support families in the future (Niu et al. 2014). Therefore, parents tend to use more severe punishment on boys than girls. Second, Chinese traditional culture which emphasizes the virginity and virtue of females may lead to lower sexual abuse and other types of abuse in females than in males (Luo et al. 2008). Last, females may have underreported child abuse because they were afraid of being judged or laughed at. Even social stigma towards risky sexual behavior still exists in China, and risky sexual behaviors of male students are considered normal, it is different for girls (Lin et al. 2011).

Although several studies have examined the prevalence of child abuse, only a few have explored the relationship between child abuse and multiple health risky behaviors among college students. Kristman-Valente et al. found that physical abuse and sexual abuse were associated with increased risk of smoking in adolescence (Kristman-Valente et al. 2013). Another study conducted among 683 adolescents in rural China found that sexual abuse was associated with higher level of engagement in smoking, binge drinking, suicidal attempt and ideation (Lin et al. 2011). The current study corroborates previous findings showing that emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse were significantly related to greater risks of several health risk behaviors among college students. In addition, we found a positive association between child abuse and the clusters of health risk behaviors in college students. This association was even stronger among students with three or more types of child abuse experiences. Our finding was consistent with Felitti et al.’s study, where a strong graded relationship was found between the number of categories of childhood exposures and risk behaviors among 13494 adults in the USA (Felitti et al. 1998). This could contribute greatly to understanding of cumulative risks of child abuse and prevention strategies regarding health risk behaviors.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, childhood trauma questionnaire measured child abuse retrospectively; therefore, under-reporting due to recalling bias or social pressure should not be overlooked. However, the latter one might have been reduced because the questionnaires were completed independently. Second, because the study was cross-sectional in design, causality between child abuse and health risk behaviors could not be established at the moment. Third, since respondents did not report precise timing of abuse, it is not possible to assess the impact of different timing of abuse on risk behaviors. Fourth, the dichotomous categorization of the risk behaviors might limit variability and combine someone who did the behavior once ever with someone who does the behavior daily.. Finally, our results might not be generalizable to Chinese young adults because the participants were only recruited from Wuhan city, China.

References

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256, 174–186.

Barth, J., Bermetz, L., Heim, E., Trelle, S., & Tonia, T. (2013). The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health, 58, 469–483.

Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1994). Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report manual. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation.

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 169–190.

Brener, N. D., Kann, L., McManus, T., Kinchen, S. A., Sundberg, E. C., & Ross, J. G. (2002). Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 336–342.

Busch, V., Van Stel, H. F., Schrijvers, A. J. P., & de Leeuw, J. R. J. (2013). Clustering of health-related behaviors, health outcomes and demographics in Dutch adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 13(1118), 1–11.

Canan, F., Yildirim, O., Ustunel, T. Y., Sinani, G., Kaleli, A. H., Gunes, C., & Ataoglu, A. (2014). The relationship between internet addiction and body mass index in Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17, 40–45.

Cao, J., & Zhang, H. (2010). Research progression on measure scale of internet addiction disorder. China Journal of Health Psychology, 18, 2.

Chen, J., Dunne, M. P., & Han, P. (2004). Child sexual abuse in China: A study of adolescents in four provinces. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 1171–1186.

Chen, J., Dunne, M. P., & Han, P. (2006). Child sexual abuse in Henan province, China: Associations with sadness, suicidality, and risk behaviors among adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health 38, 544–549.

de Bruijn, G. J., & van den Putte, B. (2009). Adolescent soft drink consumption, television viewing and habit strength. Investigating clustering effects in the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Appetite, 53, 66–75.

Felitti, V. J., Facp, Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., & Williamson, D. F. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258.

Fettes, D. L., & Aarons, G. A. (2011). Smoking behavior of US youths: A comparison between child welfare system and community populations. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 2342–2348.

Kristman-Valente, A. N., Brown, E. C., & Herrenkohl, T. I. (2013). Child physical and sexual abuse and cigarette smoking in adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 533–538.

Li, X., Wang, Z., Hou, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, J., & Wang, C. (2014). Effects of childhood trauma on personality in a sample of Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 788–796.

Lin, D., Li, X., Fan, X., & Fang, X. (2011). Child sexual abuse and its relationship with health risk behaviors among rural children and adolescents in Hunan, China. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35, 680–687.

Littleton, H., Breitkopf, C. R., & Berenson, A. (2007). Sexual and physical abuse history and adult sexual risk behaviors: Relationships among women and potential mediators. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 757–768.

Lp, P., Wong, R. S., Li, S. L., Chan, K. L., Ho, F. K., & Chow, C. (2016). Mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse in chinese populations: A meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse, 17, 571–584.

Luo, Y., Parish, W. L., & Laumann, E. O. (2008). A population-based study of childhood sexual contact in China: Prevalence and long-term consequences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 721–731.

Niu, Y., Xue, Y., & Li, W. (2014). The childhood abuse experience of college students and its relationship with family factors. China Journal of Health Psychology, 22, 1900–1903.

Patrick, M. E., Schulenberg, J. E., Martz, M. E., Maggs, J. L., O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, L. D. (2013). Extreme binge drinking among 12th-grade students in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA Pediatr, 167, 1019–1025.

Pelletier, J. E., Lytle, L. A., & Laska, M. N. (2016). Stress, health risk behaviors, and weight status among community college students. Health Education & Behavior, 43, 139–144.

Roemmele, M., & Messman-Moore, T. L. (2011). Child abuse, early maladaptive schemas, and risky sexual behavior in college women. The Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 20, 264–283.

Stallard, P., Spears, M., Montgomery, A. A., Phillips, R., & Sayal, K. (2013). Self-harm in young adolescents (12-16 years): onset and short-term continuation in a community sample. BMC Psychiatry, 13(328), 1–14.

Steptoe, A., Wardle, J., Cui, W., Bellisle, F., Zotti, A.-M., Baranyai, R., & Sanderman, R. (2002). Trends in smoking, diet, physical exercise, and attitudes toward health in European university students from 13 countries, 1990–2000. Preventive Medicine, 35, 97–104.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2013a). The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48, 345–355.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Alink, L. R. (2013b). Cultural-geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. International Journal of Psychology, 48, 81–94.

Tang, C. S. (2002). Childhood exprience of sexual abuse among Hong Kong Chinese college students. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26, 23–37.

Thayanukulvat, C., & Harding, T. (2015). Binge drinking and cognitive impairment in young people. British Journal of Nursing, 24, 401–407.

Tran, Q. A., Dunne, M. P., Vo, T. V., & Luu, N. H. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and the health of university students in eight provinces of Vietnam. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27, 26S–32S.

Wan, Y., Gao, R., Tao, X., Tao, F., & Hu, C. (2012). Relationship between deliberate self-harm and suicidal behaviors in college students. Chinese Journal Epidemiology, 33, 4.

Xu, Y., & Chen, X. (2016). Protection motivation theory and cigarette smoking among vocational high school students in China: A cusp catastrophe modeling analysis. Global Health Research And Policy, 1, 3.

Yang, Y., Huang, J., Li, C., Zhao, W., & Zhuang, X. (2016). Analysis on health risk behaviors and their influencing factors of 404 undergraduates. Journal of Medical Postgraduates, 29, 5.

Ye, Y. L., Wang, P. G., Qu, G. C., Yuan, S., Phongsavan, P., & He, Q. Q. (2015). Associations between multiple health risk behaviors and mental health among Chinese college students. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 21(3), 1–9.

Young, K. S. (2009). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(3), 1–8.

Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., Li, L., & Zhou, Y. (2005). Evaluation on reliability and validity of Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation, 9, 105–107.

Zhu, Q., Gao, E., Cheng, Y., Chuang, Y. L., Zabin, L. S., Emerson, M. R., & Lou, C. (2015). Child sexual abuse and its relationship with health risk behaviors among adolescents and young adults in Taipei. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27, 643–651.

Author's Contributions

H.Q.Q.: designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses, and wrote the paper. C.Y.L.: collaborated with the design, analyzed the data and writing of the study. L.X.: collaborated with the design, analyzed the data and writing of the study. H.Y.: analyzed the data and wrote part of the results. Y.H.J.: analyzed the data and wrote part of the results. Y.S.: collaborated with the design and writing of the study. Y.Y.L.: collaborated with the design and writing of the study. L.Q.X.: collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Yi-lin Chen and Xing Liu contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Yl., Liu, X., Huang, Y. et al. Association between Child Abuse and Health Risk Behaviors among Chinese College Students. J Child Fam Stud 26, 1380–1387 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0659-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0659-y