Abstract

Foster parents play a crucial role in providing safe and stable homes to maltreated children placed in out-of-home care and in doing so are tasked with many challenges. Understanding how foster parents are able to overcome the challenges inherent to fostering, to continue to foster children long term, and to maintain a healthy level of family functioning provides insight into key retention and recruitment efforts. Twenty foster families, all of whom had fostered over 5 years and rated as healthy functioning on the Family Assessment Device, participated in in-depth interviews to discuss the strengths their families relied on that allowed them to demonstrate resiliency. Empathy emerged as an essential foundation in the resiliency process. Foster families demonstrated empathy in three specific ways. First, was with the children they fostered, second was with the biological families of the children, and third was with the child welfare workers. Foster parents also attributed the empathy their children (fostered, adopted, and biological) demonstrated to the experience of being a foster family. The findings from this study have implications for both the child welfare workforce and foster families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite the benefits of fostering, families who care for children in out-of-home care acknowledge the stress associated with this role. Several studies exploring the challenges faced by foster parents have found that families report that they experience difficulties navigating the child welfare system, lack needed services and supports, and at times report feeling undermined or undervalued (Brown and Calder 1999; Chipungu and Bent-Goodley 2004; Heller et al. 2002; Swartz 2004). Many studies describe difficulties related to fostering children with high levels of trauma (Brown 2015; Ko et al. 2008; Pecora et al. 2009), children experiencing mental health problems (Stahmer et al. 2005), and children with disabilities (Brown and Rodger 2009). Moreover, foster parents often have to manage difficult relationships with biological families, and at times struggle with conflicted emotions of wanting reunification, but feeling at odds based on their views on what is best for the child (Hudson and Levasseur 2002).

Brown and Calder (1999) studied the challenges that foster parents perceive. In qualitative telephone interviews, 49 individuals from 30 foster families were asked to describe their challenges in response to the question, “What would make you consider stopping foster parenting?” (p. 482). The following four clusters were identified: (1) problems with the child welfare department, (2) perception of low importance, (3) safety, and (4) stress and health. Geiger et al. (2013) reported similar findings in their mixed method study examining the factors impacting foster parents’ decision to continue fostering. From a sample of 649 foster parents, the authors identified challenges such as difficultly navigating the child welfare system, decreases in the reimbursement rates and in the number of quality services to support foster children and families, and family changes at the individual level.

Challenges related to working with the child welfare system included lack of experience of workers, lack of information about the children placed with the family, bureaucratic policies, and a need for additional support (Brown and Calder 1999; Swartz 2004). Heller et al. (2002) identified similar challenges, and reported that families often have difficulty navigating the medical, educational, and mental health systems. In a more recent study, Hayes et al. (2015) examined foster parents’ perspectives of their experiences with the children’s behavioral and medical health services. Findings suggested that many of the parents experienced significant challenges with the behavioral health system, citing long wait times as particularly challenging.

Another concern expressed by foster families was not being acknowledged as respected members of the team. Heller et al. (2002) and Swartz (2004) identified challenges such as feeling undermined by workers and bureaucratic requirements, and lacking status or not being recognized for their specialized skills. Sanchirico et al. (1998) identified that foster parents desire a more active role in service planning and that being an active participant and feeling valued was associated with higher levels of job satisfaction. Other foster parents described respect in pragmatic terms such as being called back in a timely manner, and being acknowledged for the challenging work they do (Hudson and Levasseur 2002). In these studies, foster parents shared these needs even though it was not solicited, which indicates that this is of great importance to them.

As a result of these unique set of challenges, most families leave fostering within just 1 year of being licensed (Gibbs 2005). However, many foster families are able to cope and adapt such that their family unit is able to continue fostering for many years. Longevity and the ability to maintain healthy family functioning despite these challenges suggests the construct of resilience offers an explanation regarding how some families are able to sustain effective fostering for years despite the stressors associate with this important role.

Although there are several definitions of resilience in the literature, most center around adversity and an individual’s ability to cope or function successfully. When the term is used to describe children, it often takes a developmental perspective offering an explanation for how some children defy the odds and are able to overcome adversity, growing into successful adults despite trauma or abuse in childhood (Fraser et al. 1999; Garmezy 1993; Fraser et al. 2004). Specific to this process, models of resilience identify protective factors that interact with risk factors to enable the individual to avoid negative consequences associated with risk (Anderson 1997; Masten 2011). Many foster families also point to the rewards associated with fostering that help to buffer the challenges they experience (Lietz et al. 2016).

Family support or lack thereof predicts varying levels of individual functioning. With that said, resilience as a construct moves beyond just looking at individuals and can also involve a systems approach when looking at the unit of analysis as the family, rather than the individual. Family resilience refers to the process by which family units are able to sustain or even improve family functioning despite the presence of multiple risks factors. Family strengths such as spirituality, appraisal, and emotional support have been found to enhance the process of resilience in families facing adversity (Lietz 2011; Lietz 2006; Lietz and Strength 2011; Walsh 2006).

There is a wide range of studies that identify abilities and skills of foster parents that serve as strengths. Skills or characteristics often mentioned include patience, consistency, tolerance, empathy and understanding, and flexibility (Brown 2008; Coakley et al. 2007; Ivanova and Brown 2011; Lietz 2011). The ability to make connections with children, to be forgiving, organized, and to communicate clearly are also salient in the literature (Brown 2008; Ivanova and Brown 2011). Families often list support from the church, a strong marriage or partnership, and a deep commitment to helping children as motivators to continue foster parenting despite the many challenges (Coakley et al. 2007).

Empathy is an important concept that is also highlighted as relevant for effective fostering. Although the term “empathy” is used widely in both scientific and public discourse, definitions for the concept vary. In a review of these varying conceptualizations, Batson (2011) suggests that they all similarly view empathy as the ability for a person to accurately understand the “internal state of another”, which results in the desire to respond in a caring way (p. 11).

Advances in neuroscience indicate there are multiple components of empathy, demonstrating that it is a complex interchange of cognitive processes. Gerdes et al. (2010) have conceptualized empathy, using findings from neuroscience research, and created a framework that consists of the following components: (a) affective response, (b) affective mentalizing, (c) self-other awareness, (d) perspective-taking, and (e) emotion regulation.

Affective response refers to the automatic, unconscious reactions people experience when they observe another. Often referred to as mirroring, this means that when people see another in pain, they often experience an involuntary emotional and sometimes physical reaction. Although this involuntary reaction can help people care for others, without the other components of empathy, automatic reactions can also hinder the full expression of empathy when a person becomes overwhelmed by highly charged emotions or when reactions are due to bias or one’s own previous negative experiences. If, for example, foster parents are so devastated by a child’s history of abuse that they experience vicarious trauma, they will not be able to effectively care for the child.

Affective mentalizing refers to the ability to imagine the experiences of another. People do not always have to see someone in pain, to imagine what that pain might feel like. When a sister in a foster family hears about a youth’s history of moving in and out of group homes, she might find herself imagining what it would be like not having her own room or having to move with little notice. The cognitive capacity to imagine the experiences of others helps to build this component of empathy.

Self-other awareness refers to the ability to differentiate oneself from others. This component is important, in that it allows people to feel the pain of another without getting overwhelmed or lost in their pain. This component is critical for a family’s ability to sustain fostering despite knowledge of the histories children in out-of-home care bring with them. If each foster family took on the pain of each child for whom they cared, they would quickly face burnout, leading to a placement disruption and potentially exiting fostering.

Perspective-taking involves the cognitive processes needed to accurately understand the experiences of another. This requires a level of cognitive flexibility that allows one to consider multiple explanations for a particular behavior such as a foster parent who can ask, “I wonder if my foster daughter is having a hard time connecting with me because she misses her own mother?”. Finally, emotion regulation involves the ability to feel with another, without becoming overwhelmed by high levels of negative emotions. Remaining emotionally grounded and demonstrating a level of emotional stability and consistency is important both for the foster parents as well as for the children they foster. (For further description of these components, see Segal et al. in press.)

Although empathy is often considered important to effective fostering (Brown 2008; Coakley et al. 2007; Ivanova and Brown 2011), there is a dearth of research that explores how empathy is understood and cultivated within a child welfare context (Mullins 2011). Foster parents face challenges in caring for their foster children due to personal, systemic, and related difficulties. What is more, they may have negative perceptions of the child’s biological parent or parents involved in a neglect or abuse case, which can hinder the ability to engage in shared parenting and ultimately could hinder opportunity for reunification (Edelstein et al. 2001). A lack of empathy in part of the child welfare worker can impact the service implementation and success of the family intervention (Mullins 2011); similarly, a lack of empathy in part of the foster parent can affect his or her ability to be aware of the children’s difficulties and to provide a supportive response (Edelstein et al. 2001). Conversely, the presence of empathy can allow for accurate understanding of the experiences of foster children, birth parents, foster parents, and workers in a way that could advance the complicated work of child welfare (Lietz 2011).

Although some studies have focused on understanding empathy in child welfare workers (Mullins 2011; Luke and Banerjee 2012; Conrad and Kellar-Guenther 2006) and in children who have experienced abuse or neglect (Luke and Banerjee 2012), much less is known about empathy among foster families and its role in successful fostering, and willingness to continue foster parenting (Lietz 2011; Faver and Alanis 2012). The objective of this exploratory study was to better understand how empathy is manifested in successful foster parents and how empathy contributes to resilience from the perspective of foster parents themselves.

Method

Participants

The sample included 7 single-parent households and 13 two-parent households. Six families identified as Caucasian, 12 as multi-racial, and 2 did not identify their race. The number of children fostered ranged from 3 to 25 or more children (M = 14.9) over the course of 5–26 years (M = 9.4 years). All families in the sample had provided non-relative foster care, four had also provided kinship care, and one was licensed as a therapeutic foster family.

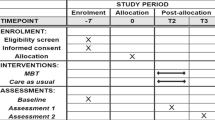

Procedure

A mixed methods, sequential explanatory design (Creswell 2003) was used to identify a purposive sample of licensed foster families who had fostered for over 5 years and who rated within the healthy range on the family assessment device (FAD; Epstein et al. 1983), a standardized measure of family functioning. A link to an online survey was sent to all licensed foster parents in one southwestern US state with a current email address on file. Of the 1864 licensed foster parents contacted, 681 responded to the survey, representing a 36.5 % response rate. Twenty of the 71 families who met study criteria were selected to ensure diversity among racial/ethnic group, geographic location, and family makeup.

Families were asked to participate in two in-depth interviews to understand how they manage the stress associated with fostering. All adult members of the family were invited to participate in the interviews. Interview participation varied, with adult children (living or not living in the home) and one or both parents participating in one or both of the interviews. In fact, four of the families interviewed included adult children.

Researchers used a narrative interviewing approach, which involves using a limited number of open-ended questions that allow the research participants the ability to guide the discussion and therefore the content and depth. This approach to interviewing provides families the opportunity for families to engage in more storytelling vs. a question/answer format. Additionally, active listening is used to encourage examples, illustrations, and elaborations of the family’s experiences. This encourages the participant’s voice to be heard, while decreasing the role of the researcher in the interview. The in-person interviews included six open-ended questions about the foster family’s challenges, strengths, and how they believed that they had been able to overcome the challenges associated with fostering and in everyday life. Questions such as, “What has helped your family to cope with the challenges of fostering?” and “If you were advising a new foster parent about how to be successful in fostering, what might you suggest to that person based on your own experiences?” helped families to discuss the internal strengths and external resources that supported their process of coping and adaptation.

The first interviews ranged from 45 to 136 min (M = 88.9 min). Prior to the interview, time was also spent gaining informed consent, talking about the process of the interview and study, and for summarizing and debriefing when the interview was complete. Families were also invited to participate in a second interview, allowing the family time to reflect on the first interview and provide additional detail as necessary. Eighteen of the 20 families participated in a second interview.

Measures

The FAD (Epstein et al. 1983) is a standardized measure used to assess multiple components of family functioning. The FAD has established psychometric properties and is a widely used measure (Epstein et al. 1983). In the study, the scale was found to have a high level of internal consistency with this sample (α = 0.89). The short form was chosen for the purpose of this study to minimize the length of the overall survey; it measures general functioning of a family unit. The short form includes 12 items that ask a family’s level of agreement on a 4-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” to statements such as, “we can express feelings to each other”, “we are able to make decisions about how to solve problems”, and “we confide in each other”. The FAD has an established cut-off score to distinguish a level of healthy family functioning that allowed the research team to identify families who had fostered for 5 years or longer while maintaining healthy functioning of the family unit.

Data Analyses

Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by two researchers using NVivo 10 software. Four researchers conducted the interviews and analyzed the data independently using the template method. With the template approach, all meaning units were analyzed according to the model of family resilience that emerged in previous research, which included 10 family strengths (Lietz 2006; Lietz et al. 2016; Lietz and Strength 2011). Any meaning units that did not fit the template were coded as “no code”, allowing new themes to emerge that may not fall within the model. Meaning units within the “no code” category were further analyzed using open coding to identify additional themes. Through this process, a new theme emerged that seemed consistent with the understanding of empathy rooted in neuroscience. As a result, we went back and recoded the data to identify ways in which the components of empathy were embedded in these narratives.

To increase trustworthiness of the findings in the study, several strategies were used, including the use of an audit trail, reflexivity, peer debriefing, triangulation by observer, and member check. The research team members met regularly to process experiences related to the interviews, coding, and analysis. An audit trail of meetings and what transpired at the meetings, the researchers’ notes regarding reflections on each interview, and analytical strategies was kept. Two researchers conducted coding for each interview, and a foster parent and advocate was included on the research team to ensure trustworthiness of our research procedures from recruitment, to data collection and analysis.

Results

Foster families in the study discussed empathy in various contexts and view it as an important way to develop family strengths that has helped them to overcome the challenges associated with fostering. Findings indicate resilient foster families demonstrate empathy for the children for whom they care, the biological families of the children, and the child welfare workers with whom they work. In addition, families talked about how fostering has provided the basis for empathy in the children in their home (fostered, adopted, and biological). The participants perceived that the presence of interpersonal empathy within their family units allowed them to better manage stress and navigate difficult circumstances in a more productive way. Many were able to gain greater insight or understanding of the needs of the children in their care and their families. Families also described how important it was for them to model empathy with the children in their care for their other children and family members.

Empathy for the Children

Foster families described the need to have empathy in order to have a greater understanding of the trauma history of the children placed with them and their resulting needs. They talked about empathy allowing them as caregivers to understand the children in a deeper way to uncover the reasons behind their behavior, feelings, and thoughts. As one foster parent explained, “Compassion is huge. But if you don’t understand what you’re up against, then you know, you can’t possibly work with them”. Similarly, another parent explained understanding the child helped her to adapt her approach when stating:

I just think empathy is just so important when you’re dealing with foster kids, ‘cause they’re scared, they’re confused, they’re hurt. A lot of times they’ve been abuse[d] or neglected, and…being able to reach out to them in a non-threatening way and make them feel comfortable, it is the very first thing you’ve got to do.

Many foster parents talked about the importance of empathic accuracy in their response to the children in their care. When they were able to understand the meaning of a child’s behavior, they could adapt their parenting approach. They were also better able to accept negative behaviors when they had insight into what was happening. Affective mentalizing became important as they imagined a child’s experiences when receiving information from the caseworker. The lack of information or their own difficulty with this cognitive process can hinder the full expression of empathy and hinder the placement.

Empathy for the Biological Family

Foster families also discussed how empathy and the ability to better understand the perspective of the birth parents helped ease the transition for the children and improve relationships between foster and birth parents, enhancing the opportunity for sharing parenting. For example, one foster parent talked about supporting the biological mother and the child she cared for even after leaving her home when she explained:

Mom has done what she’s needed to do to get her kids back…[I like to] be a support to them when they go home. I - all of my kids that have returned have my phone number and they can contact me if they need me as well as the parents, the bio-parents. Even if I don’t like them. I don’t have to be friends with them. I do have to be friendly. And so I think, like I said, once it—once it starts feeling like work and I start to become or feel angry, or not have compassion for the bio-families like I do now, then I’ll need to stop.

This foster parent highlights not only the importance of compassion and care for others but also references boundary setting and the self-other awareness dimension of empathy. Engaging in shared parenting does not mean becoming friends with biological parents, but it does involve having the ability to care with others, which is needed to develop supportive relationships.

Foster families talked about having a choice about how they view the biological parents. They discussed that it would be easy to have a negative impression of biological parents based on the circumstances and this negativity could lead to automatic reactions that do not promote empathy. However, the families we interviewed perceived their capacity to engage in affective mentalizing and perspective-taking allowed them to understand the challenges faced by birth parents, something they felt was important to successful fostering. For example, resilient foster families seemed able to view parents as human beings who made mistakes, while acknowledging history such as intergenerational transmission of abuse or structural factors such as poverty as contributing factors to the situation that resulted in the placement of their child in foster care. Illustrating this point, one foster parent explained:

They [biological parents] were truly genuine people who made bad choices. And I think foster parents want to blame them, rather than understand them. And I think it’s important that we [foster parents] step back and take the time to meet those people [biological parents], because they’re people too. And they may have trauma that they’ve experienced that they haven’t dealt with that is now preventing them from being good parents themselves. And if they’re willing to accept those, that the things that happened to them and their children aren’t their fault, and make those changes, then they deserve all those kids back. And we need to work with them as part of the team.

Similarly, another parent explained:

Recently, I’ve been reminded that you have to remember the parents are people, too, the bio parents. I recently went with one of my foster families to meet the bio parents for the first time and I went there as a support to her. And afterwards, we both talked about how wonderful the bio parents were.

The ability to separate behavior such as child maltreatment from one’s inherent worth and dignity as a human being is difficult and yet highlighted by these foster families as essential to working alongside birth parents in shared parenting.

Finding commonality and ways to relate to the birth parents seemed to enhance this ability to connect on a human level. For example, one foster mother came to the hospital to pick up a newborn baby and decided to come back the next day after thinking about the experience of the birth mother. She realized that mothers:

…go through the same thing. You all have the same hormones, you go through this, you know…And I told her, I said, ‘I’m not gonna take your baby today because you’re very upset and I’ve given you a lot of information. I’m gonna come back tomorrow so you have all the rest of the day tonight to say goodbye, give him all the kisses. I’ll come back tomorrow’.

Asking questions like, “how would I feel” demonstrates the perspective-taking and cognitive flexibility needed to accomplish empathic understanding.

Empathy for Child Welfare Workers

In addition to developing empathy for birth parents, foster families also highlighted the importance of having empathy for professionals working in the child welfare system by acknowledging the barriers they too experience. In our interviews, foster families expressed their understanding of the barriers and limitations child welfare workers often face when working in the child welfare system. One parent shared, “Sometimes there’s just a lot of red tape in the system where the case managers have their hands tied up”. Another foster parent explained the importance of, “Remembering that case managers are doing a job they’ve been directed to do, they’re not bad guys. Even if they’re not calling you back regularly. They’re busy and out in the field, too”. The cognitive flexibility that is part of the full array of empathy allows foster parents to consider more generous meanings to behaviors such as not returning a phone call. This in turn helps foster parents to cope with the realities of being part of a very stretched public child welfare system.

These foster families went on to discuss how being shown empathy has helped them to establish and maintain better relationships with child welfare workers and other related professionals with whom they work. As one foster parent described:

When you build rapport with those good ones too and then you’re willing to take kids from those good ones again. Because you know they’ve been supportive. You know that they understand where you’re coming from or at least try to.

Other foster parents described empathy in their relationships with child welfare workers being exhibited through workers including them as part of the team to support the child and family.

Fostering as a Means of Cultivating Empathy in Children

Foster families in the study discussed how they believe that being a foster family and having foster children in the home teaches their own children to have empathy. They talked about how fostering has brought their family closer together and strengthened the family. For example, one parent explained:

I think it [fostering] helped the kids…they learned that many kids that go through foster care have gone through a lot of trauma at a young age and how it affects their ability to learn. So, they have watched the struggles, but they still help them with easy math and they have to read out loud to my kids once a week, and they’re okay with that. This is how they are and this is what we do.

Foster parents also described how they believe that fostering helps to instill a model of empathy, caring, and understanding of others in the children in the home (foster, adopted, and biological). Families talked about how they felt that their children were learning how to understand others, read their emotions, see where they were coming from, and how to treat others with respect and care as a result of fostering in the home. For example, one foster parent stated:

She [biological daughter] has a lot of empathy for other children and that’s something her kindergarten teacher—she’s in the first grade now—but her kindergarten teacher said over and over again that she’s very sensitive to other people’s emotions and very caring. I think that’s come from foster care.

Another foster parent explained, “He’s [biological son] having good experiences. And he doesn’t always like when they leave, and he doesn’t always like all of the kids…but, you know, again it’s teaching him compassion”. An adult child described his mother and what fostering has taught him and shared, “It really blows my mind how much patience she has. So, it teaches me a lot, I think I could be upset a lot more than I do and it just—you just look at the bigger picture and it’s like, just really not worth it, you know”.

Several of the families interviewed talked about their adult children who have gone on to become licensed foster parents themselves or gone into helping professions as adults. In describing how having foster children in their home helped her son develop empathy, which has impacted him as an adult, one foster mother shared:

That’s teaching him compassion that he’s a lucky one, he got to have a forever home…he has compassion for children, too, and he got into the behavioral health field helping older kids. So I think it’s a good thing, too…that hopefully it opens their eyes that there are people in the world who care.

Wagaman and Segal (2014) discuss the importance of contextual understanding that is derived from exposure to experiences that are different than our own. Social empathy develops when a person’s experiences help them to increase understanding and concern about a particular social issue. In this same way, children who grew up in families who foster may develop social empathy leading them to want to help children as adults themselves.

Discussion

The process of family resilience offers an explanation regarding the strengths and process by which families engage in an adaptational process that allows them to cope effectively with stress (Lietz 2011; Lietz 2006; Walsh 2006). As outlined in the literature review, there is no question that fostering is stressful. Yet, many foster families care for children in out-of-care for years, some fostering many children over extended periods of time. The process of family resilience offers an explanation for how some families are able to sustain effective fostering while maintaining the health and well-being of their family unit (Lietz et al. 2016).

The important contribution of this study is to highlight the role of empathy as relevant in enhancing the integration of multiple strengths, as being particularly relevant for families who foster. Rogers (1957) identified empathy as a necessary core condition to forming a helping relationship that facilitates the change process. This research suggests empathy is similarly a necessary condition for cultivating the process of resilience. The full expression of empathy, integrated through the five components, emerged as critical for families who foster offering implications for practice. First, it is not difficult to imagine foster parents having automatic affective reactions when exposed to stories of maltreatment that accompany children in their care. Mindfulness interventions that can help foster parents recognize and in some cases reshape automatic negative reactions may be important to their capacity to sustain effective fostering over time.

Affective mentalizing allows foster parents to imagine what others are going through, including the children for whom they care, the birth parents with whom they must co-parent, and the child welfare workers with whom they collaborate. Affective mentalizing is assisted when foster parents are provided ample information about the child’s history. Foster parents express that they often do not receive information they feel is adequate to care for the child placed with them (Lietz et al. 2016). An important implication for practice is for child welfare workers to provide child histories to foster parents in order to support the process of affective mentalizing. In addition, child welfare agencies serving foster parents could provide relevant training and mentoring of foster parents that could also support this process by offering an explanation into the familial, structural, and societal effects that impact a person’s capacity to parent effectively. Practitioners working with foster families should also be trained about the importance of empathy when working with families involved in the child welfare system.

Engaging in boundary setting and helping foster parents cultivate a strong sense of self-other awareness is another important dimension to empathy (Gerdes et al. 2011). Helping foster parents to clarify roles, set clear expectations, and understand what their role is in supporting efforts toward reunification, when that is the case plan, is important. Training that can help to develop empathy and specifically emotional boundaries to prevent vicarious trauma and resulting burnout could reduce placement disruptions and extend the time a family chooses to foster (Brown and Calder 1999; Chipungu and Bent-Goodley 2004; Geiger et al. 2013). Considering the families in this study all fostered for 5 years or longer suggests some longevity benefits when the full array of empathy is developed.

Similarly, creating opportunities for perspective-taking is also important. Agencies can provide training and mentoring of foster parents and can help increase the cognitive flexibility needed when adapting one’s home, schedule, and routine to meet the needs of a foster child. Interventions that support the practice of shared parenting should have a component that allows for cognitive restructuring related to a family’s preconceived notions about what it means to foster. Family counseling might also be helpful in some circumstances as families seek to adapt to the challenges associated with fostering.

Finally, emotional regulation is required to help foster families manage the practical and emotional complexity associated with fostering. This study offers implications for policymakers and agency practitioners. For example, allowing foster families to take breaks in between placements gives them time to grieve, something that is important to their emotional state. Providing respite and other opportunities for taking a break can also support the development of emotion regulation. Foster parents want to feel valued and have a relationship with the child welfare worker built upon trust and mutual respect that allows for an understanding and appreciation of the grief and emotional turmoil fostering can entail (Chipungu and Bent-Goodley 2004). Again, mindfulness interventions that assist families in both recognizing and expressing emotion may also support the process of fully realizing the components of empathy.

Understanding how the elements of empathy function in the resiliency process provide implications for both foster parents themselves and the providers who work with foster families, including child welfare workers. Empathy is a skill that can be enhanced and taught (Gerdes et al. 2011). Through training opportunities, foster parents can learn the elements of empathy, and through mentoring foster parents can see empathy modeled. Training for providers should include how the foundation of empathy supports resiliency in foster families and be encouraged to support and acknowledge the importance of affective response, affective mentalizing, self-other awareness, perspective-taking, and emotion regulation within foster families. Additionally, there are opportunities for policies to reflect the need for more empathy-based interactions and learning. During recruitment, agencies might consider assessing for empathy and offering pre-service and continuing training for foster families as well as practitioners working with foster families that center around empathy and its components.

There were limitations to this study. The study included 20 families who foster across one state. It is possible there was some bias created by the sampling process and/or the location of the study. In addition, the initial research question did not focus specifically on empathy; the role of empathy emerged from the narratives of a sample of resilient foster families as a necessary condition for their process of resilience. There is more to be known about how foster families experience empathy, suggesting future research is needed. Despite these limitations, the findings are transferable in that they offer areas of consideration for those who license, train, mentor, and provide services for families who foster.

References

Anderson, K. (1997). Uncovering survival abilities in children who have been sexually abused. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 78(6), 592–599.

Batson, C. D. (2011). Altruism in humans. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Brown, J. D (2008). Foster parents’ perceptions of factors needed for successful foster placements. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17(4), 538–554.

Brown, J. D., & Rodger, S. (2009). Children with disabilities: problems faced by foster parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(1), 40–46.

Brown, J. M. (2015). Therapeutic moments are the key: foster children give clues to their past experience of infant trauma and neglect. Journal of Family Therapy, 37(3), 286–307.

Brown, J., & Calder, P. (1999). Concept-mapping the challenges faced by foster parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 21(6), 481–495.

Chipungu, S. S., & Bent-Goodley, T. B. (2004). Meeting the challenges of contemporary foster care. The Future of Children, 14(1), 75–93.

Coakley, T. M., Cuddeback, G., Buehler, C., & Cox, M. E. (2007). Kinship foster parents’ perceptions of factors that promote or inhibit successful fostering. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(1), 92–109.

Conrad, D., & Kellar-Guenther, Y. (2006). Compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among Colorado child protection workers. Child Abuse and Neglect, 30(10), 1071–1080.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Edelstein, S. B., Burge, D., & Waterman, J. (2001). Helping foster parents cope with separation, loss, and grief. Child Welfare, 80(1), 5–25.

Epstein, N. B., Baldwin, L. M., & Bishop, D. S. (1983). The McMaster family assessment device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 9(2), 171–180.

Faver, C. A., & Alanis, E. (2012). Fostering empathy through stories: a pilot program for special needs adoptive families. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(4), 660–665.

Fraser, M. W., Galinsky, M. J., & Richman, J. M. (1999). Risk, protection, and resilience: toward a conceptual framework for social work practice. Social Work Research, 23(3), 131–143.

Fraser, M. W., Kirby, L.D., & Smokowski, P. R. (2004). Risk and resilience in childhood. In M. W. Fraser (Ed.), Risk and resilience in childhood: an ecological perspective (pp. 13-66). Washington DC: NASW Press.

Garmezy, N. (1993). Children in poverty: resilience despite risk. Psychiatry, 56(1), 127–136.

Geiger, J. M., Hayes, M. J., & Lietz, C. A. (2013). Should I stay or should I go? A mixed methods study examining factors influencing foster parents’ decision to continue or discontinue fostering. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 1356–1365.

Gerdes, K. E., Segal, E. A., & Lietz, C. A. (2010). Conceptualising and measuring empathy. British Journal of Social Work, 40(7), 2326–2343.

Gerdes, K. E., Segal, E. A., Jackson, K. F., & Mullins, J. L. (2011). Teaching empathy: a framework rooted in social cognitive neuroscience and social justice. Journal of Social Work Education, 47(1), 109–131.

Gibbs, D. A. (2005). Understanding foster parenting: using administrative data to explore retention. Report prepared by RTI International for U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hayes, J., Geiger, J. M., & Lietz, C. A. (2015). Navigating a complicated system of care: foster parent satisfaction with behavioral and medical health services. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(6), 493–505.

Heller, S. S., Smyke, A. T., & Boris, N. W. (2002). Very young foster children and foster families: clinical challenges and interventions. Infant Mental Health Journal, 23(5), 555–575.

Hudson, P., & Levasseur, K. (2002). Supporting foster parents: caring voices. Child Welfare, 81(6), 853–877.

Ivanova, V., & Brown, J. (2011). Strengths of aboriginal foster parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(3), 279–285.

Ko, S. J., et al. (2008). Creating trauma-informed systems: child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(4), 396–404.

Lietz, C. (2006). Uncovering stories of family resilience: a mixed methods study of resilient families, part 1. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 87(4), 575–582.

Lietz, C. A. (2011). Empathic action and family resilience: a narrative examination of the benefits of helping others. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(3), 254–265.

Lietz, C. A., Julien-Chinn, F. J., Geiger, J. M., & Piel, M. J. (2016). Cultivating resilience in families who foster: understanding how families cope and adapt over time. Family Process.

Lietz, C., & Strength, M. (2011). Stories of successful reunification: a narrative study of family resilience in child welfare. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 92(2), 203–210.

Luke, N., & Banerjee, R. (2012). Maltreated children’s social understanding and empathy: a preliminary exploration of foster carers’ perspectives. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(2), 237–246.

Masten, A. S. (2011). Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: frameworks for research, practice, and translational synergy. Development and Psychopathology, 23(02), 493–506.

Mullins, J. L. (2011). A framework for cultivating and increasing child welfare workers’ empathy toward parents. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(3), 242–253.

Pecora, P. J., Jensen, P. S., Romanelli, L. H., Jackson, L. J., & Ortiz, A. (2009). Mental health services for children placed in foster care: an overview of current challenges. Child Welfare, 88(1), 5–26.

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95–103.

Sanchirico, A., Lau, W. J., Jablonka, K., & Russell, S. J. (1998). Foster parent involvement in service planning: does it increase job satisfaction?. Children and Youth Services Review, 20(4), 325–346.

Segal, E. A., Gerdes, K. E., Lietz, C., Wagaman, A., & Geiger, J. M. Assessing empathy. New York: Columbia University Press (in press).

Stahmer, A. C., Leslie, L. K., Hurlburt, M., Barth, R. P., Webb, M. B., Landsverk, J., & Zhang, J. (2005). Developmental and behavioral needs and service use for young children in child welfare. Pediatrics, 116(4), 891–900.

Swartz, T. T. (2004). Mothering for the state: foster parenting and the challenges of government-contracted carework. Gender and Society, 18(5), 567–587.

Wagaman, M. A., & Segal, E. A. (2014). Relationship between empathy and attitudes toward government intervention. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 41(4), 91–112.

Walsh, F. (2006). Strengthening family resilience. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Appropriate informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Geiger, J.M., Piel, M.H., Lietz, C.A. et al. Empathy as an Essential Foundation to Successful Foster Parenting. J Child Fam Stud 25, 3771–3779 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0529-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0529-z