Abstract

Prosocial behavior is considered an important dimension of positive development. Although previous research suggests the quality of children’s early relationships may influence prosocial behaviors, the specific contributions of mother, father and teacher to children’s prosocial behavior have been less examined. This is a cross-sectional study that investigates (a) the combined associations between mother–, father– and teacher–child relationships, and prosocial behavior in 168 children aged 36–72 months, and (b) the mediating role of the teacher–child relationship in the association between the parent–child relationship and prosocial behavior. Results suggested a positive link between the quality of relationships with early caregivers and children’s prosocial behavior. The quality of both father– and teacher–child relationships were found to have a direct association with children’s prosocial behavior. The quality of the mother–child relationship was indirectly linked to children’s prosocial behavior, via the teacher–child relationship. Results suggesting connections between multiple relational contexts were discussed based on the notion of internal working models proposed by attachment theory. Mothers’ and fathers’ contributions to children’s prosocial behavior were also discussed considering differences on relational styles and changing roles of mothers and fathers from dual-earner families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Early childhood is an important period for the development of prosocial behavior (Hay et al. 2004), usually defined as the voluntary actions intended to benefit others (Eisenberg et al. 2006). Prosocial behaviors, such as helping, comforting and sharing, emerge between the first and second year of life, progressively increasing in frequency and variety during the early childhood period (Zahn-Waxler et al. 1992). There is a well-documented relation between prosocial behavior and several dimensions of adaptive development, such as social acceptance and friendship, psychosocial adjustment and academic achievement (Caprara et al. 2000; Clark and Ladd 2000; Hay and Pawlby 2003; Sebanc 2003). Research has been focusing on the conditions that might foster children’s prosocial behavior, highlighting the importance of early social environments, such as family and school.

There are several studies suggesting the association between children’s prosocial behavior and distinct positive features of the parent–child relationship, namely parental involvement, warmth, responsiveness, sensitivity, connectedness, prosocial modeling and parental encouragement of children’s emotional expression (Brophy-Herb et al. 2010; Bryant and Crockenberg 1980; Clark and Ladd 2000; Garner 2006; Kärtner et al. 2010; Kiang et al. 2004; Koestner et al. 1990). In a 26-year longitudinal study, Koestner et al. (1990) found early paternal involvement in child care to be significantly associated with empathic concern at the age of 31 years. Additional predictors of adults’ empathy were maternal tolerance of dependent behavior and maternal inhibition of the child’s aggression in early childhood (Koestner et al. 1990). It appears that children who experience warmth and responsive relationships with parents are more likely to develop a sense of connection with others and the predisposition to recognize and respond to others’ feelings and needs (Hastings et al. 2007; Staub 1992). Sensitive parenting (i.e., parents’ ability to acknowledge and respond appropriately to children’s distress cues and emotional needs) provides children with the experience of a reliable care, fostering the expectation of fulfilled needs and protection in stressful situations. A sensitive parenting interaction style is associated with other-oriented behavioral models that children may use in social interactions with peers and other adults (Hastings et al. 2007). The assumption that the quality of the mother–child early relationship affects the child’s socio-emotional development has been supported by attachment theory. This theoretical framework posits that early attachment-related experiences support children’s development of internal working models of relationships. These models set the foundations for children’s later social-emotional functioning, by giving meaning and guiding expectations in social interactions (Bowlby 1988; Main et al. 1985; Stayton et al. 1971; Waters et al. 1986). The establishment of secure attachment relationships with primary caregivers supports the internalization of positive models of relationships, predisposing the children to act prosocially (Hastings et al. 2007; Sroufe and Fleeson 1986). In this perspective, children’s experience of positive attachment relationships may foster children’s prosocial behavior through the development of internal models of relationships based on interactive reciprocity and empathic engagement with others. Some studies conducted within this framework showed securely attached children are more likely to respond prosocially to mothers’, peers’ and strangers’ stress (Denham 1994; Kestenbaum et al. 1989).

Previous studies have mainly focused on the way prosocial behavior is influenced by the child’s relationship with its mother, neglecting the role of the father. There are significant differences between the quantity and quality of mothers’ and fathers’ involvement with the child (Parke 2002 for a review). Differences in the amount of time mothers and fathers spend with the child, the type of joint activities they perform and their style of interaction, have been reported (Hallers-Haalboom et al. 2014; Lewis and Lamb 2003; McBride and Mills 1993; Roopnarine et al. 2005; Yeung et al. 2001). Although both parents can be equally sensitive and responsive, mothers tend to be verbal and didactic in their play, while fathers tend to engage in a more physically stimulating and unpredictable play (Lewis and Lamb 2003; Parke 2002). When examining mothers’ and fathers’ involvement in childrearing activities, Yeung et al. (2001) found mothers spent most of their time in caring, teaching and household activities, whereas fathers spent most of their time in play activities. Due to socioeconomic changes in modern societies, such as the growing participation of women in the workforce, fathers’ involvement has been gradually increasing, reducing the gap between mothers’ and fathers’ participation in family life (Bonney et al. 1999; Cabrera et al. 2000; Yeung et al. 2001). These socioeconomic changes have implications for the relative effects of mother– and father–child relationships on children’s outcomes, such as prosocial behavior. In fact, recent studies suggested mothers and fathers have unique contributions to child prosocial behavior (Carlo et al. 2010; Lindsey et al. 2010, 2013). For instance, Lindsey et al. (2013) found mothers’ and fathers’ emotional expression to have independent effects over child prosocial behavior. Because mothers and fathers are likely to be involved with children in different types of activities, opportunities to foster and model behaviors may vary by caregiver. These distinctive contributions are particularly important to address in dual-earner families, where mothers and fathers display a more equal participation in their children’s life (Gottfried et al. 2002 for a review).

In early childhood, along with mothers and fathers, teachers are one of the most relevant agents in children’s development (Pianta et al. 2003 for a review). A close teacher–child relationship, characterized by warmth, affection and open communication, has been associated with children’s prosocial behavior (Howes 2000; Pianta and Stuhlman 2004; Roorda et al. 2014; Spivak and Howes 2011). In fact, results from Myers and Morris (2009) suggested teacher–child closeness relates to children’s prosocial behavior, regardless of their children’s temperament. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the joint associations of mother–, father– and teacher–child relationships with the child’s prosocial behavior. However, some studies investigated the role of mother– and teacher–child relationships in child prosocial behavior (Howes et al. 1994; Kienbaum et al. 2001; Mitchell-Copeland et al. 1997). These studies showed a significant association between the quality of the teacher–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior, but not between the mother–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior (Howes et al. 1994; Kienbaum et al. 2001; Mitchell-Copeland et al. 1997). Kienbaum et al. (2001) suggested the existence of a context effect to explain these results. In these studies, the teacher–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior were measured in the same context, namely the preschool context. Unlike mothers, teachers were part of the context in which prosocial behavior was measured. Therefore, the contribution of the teacher–child relationship to children’s prosocial behavior was more evident than the contribution of the mother–child relationship (Kienbaum et al. 2001).

Similarities between the characteristics of parental and non-parental relationships have been emphasized by prior literature, suggesting that early relationships with parents may shape children’s later relationships with non-parental caregivers, such as teachers (Sabol and Pianta 2012). The theoretical assumption behind these findings is that the history of early interactions with parents sets the foundations for the establishment of children’s relationships with nonparental care providers (Sroufe and Fleeson 1986). Some studies in the field of early childhood education have examined the link between the quality of parent– and teacher–child relationships, suggesting children who experienced positive relationships with their parents are more likely to display positive relationships with teachers (Howes and Matheson 1992; O’Connor and McCartney 2006; Sabol and Pianta 2012). Therefore, it may be reasonable to suppose that the teacher–child relationship can mediate the association between children’s relationships with their parents and developmental outcomes, like prosocial behavior in the classroom (Sabol and Pianta 2012). This hypothesis has not been tested by the research to date. Research efforts addressing the paths through which the characteristics of both the father–child relationship and the mother–child relationship affect children’s prosocial behavior, considering the mediating role of the teacher–child relationship, can contribute to advance knowledge in this area.

The overall purpose of the current study is to understand the role of early relationships with the mother, the father and the teacher in children’s prosocial behavior. This study focused on the contributions of positive features of the parent–child relationship (i.e., attachment, involvement and confidence) and of the teacher–child relationship (i.e., closeness) to children’s prosocial behavior. The first goal was to investigate associations among children’s prosocial behavior and mother–, father– and teacher–child relationships. Considering the theoretical framework and empirical evidence, it was hypothesized that the quality of children’s relationships with their parents would be positively related to children’s prosocial behavior. Furthermore, a positive link between teacher–child closeness and children’s prosocial behavior was expected. The second goal for this study was to examine whether the quality of the teacher–child relationship mediates the association between the mother–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior, as well as the association between the father–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior. Assuming a partial mediation, it was expected that the quality of mother– and father–child relationships would be directly and indirectly associated with child prosocial behavior, via the teacher–child relationship.

Method

Participants

The participants were 168 children (46 % girls) aged between 36 and 76 months (M = 53.65, SD = 9.44). In Portugal, the preschool period takes place during the 3 years preceding compulsory schooling. Most Portuguese children enroll in private or public preschool programs at age 3, remaining in the same preschool classroom until age 6. Children were recruited from 50 preschool classrooms, chosen from 25 public and private preschools in the metropolitan area of Porto, Portugal. Children were attending preschool for an average of 27 months (M = 27.08, SD = 16.46), ranging from less than 1 year of school attendance (22.70 %, n = 35) to more than 4 years of school attendance (29.90 %, n = 46). Teachers were all women with a university degree in education and aged between 22 and 54 years (M = 39.50, SD = 8.62).

Children came from families with dual-earner and cohabiting parents. Most of the participating parents had a full-time job, working for an average of 42.92 h per week (SD = 9.03). Fifty-four percent (n = 90) of the families had one child while 42 % (n = 71) had two children. Mothers’ age ranged from 23 to 49 years (M = 35.39, SD = 4.48) and fathers’ age ranged from 24 to 50 years (M = 36.64, SD = 4.66). Nearly 2 % of mothers (n = 3) and 7 % of fathers (n = 11) had primary education, 39 % of mothers (n = 66) and 55 % of fathers (n = 93) had secondary education, while 59 % of mothers (n = 99) and 38 % of fathers (n = 64) had some form of higher education. This sample is quite characteristic of the Portuguese dual-earner population, regarding family structure, parents’ age range and working hours (INE 2011). However, it includes a larger proportion of parents with higher education.

Procedure

This study uses data from preschool children, their families and teachers, collected within a broader research project aiming to understand the impact of work–family dynamics on parenting and children’s development. The research project was approved by the faculty’s institutional review board (IRB). Data were collected 6 months after the beginning of the school semester, as part of the baseline assessment of a longitudinal study. After obtaining permission from schools, the study was explained to teachers and parents. The parents’ participation rate was 38 %. This rate was equivalent among parents of children from public (37 %) and private (39 %) schools. Following written informed consent, parents and teachers were asked to fill in an individual questionnaire focusing on their parenting/teaching experience and on some indicators of the child’s development. Parents were instructed to complete separate surveys, to place the surveys in individual envelopes and return the closed envelopes to their children’s teacher.

Measures

Children’s prosocial behavior was measured using the prosocial behavior sub-scale from the Portuguese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire—parent and teacher versions (SDQ, Goodman 1997; Marzocchi et al. 2004). A multi-informant approach was adopted, with independent ratings from mothers, fathers and teachers. The SDQ is a widely used brief behavioral questionnaire for assessing children’s psychosocial adjustment and has been successively used in many published studies across cultures (Marzocchi et al. 2004; Woerner et al. 2004). To complete this questionnaire caregivers are asked to rate 25 child behavioral attributes (some positive and others negative), using one of three possible response categories (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = certainly true). The SDQ’s prosocial sub-scale has 5 items focusing on distinct prosocial actions that children may adopt in their daily routine (e.g., “Shared readily with other children”; “Helpful if someone is hurt, upset or feeling ill”). High scores on this sub-scale reflect high levels of prosocial behavior. The items’ average score can be classified as “Normal” (from 1.2 to 2), “Borderline” (1) and “Abnormal” (from 0 to .8). For the current study, internal consistency reliability was tested using Cronbach alpha for mothers (alpha = .64), fathers (alpha = .64) and teachers (alpha = .78). Consistently with previous research (Stone et al. 2010, for a review), parents’ ratings showed lower reliability, when compared to teachers’ ratings.

Mothers and fathers reported on the parent–child relationship independently by completing a Portuguese version of the Parenting Relationship Questionnaire—Preschool Form (PRQ, Kamphaus and Reynolds 2006; Vieira et al. 2013). The PRQ was previously studied in a Portuguese sample of parents, revealing good psychometric properties (Vieira et al. 2013). This 43-items questionnaire was developed to assess distinct dimensions of parenting relationships, including items about thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and situations that parents may experience in caring experiences with their child. Parents are asked to express their perspective on the different statements by using a four level Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). For the present study the following sub-scales were used: (a) attachment (9 items; e.g., “When upset, my child comes to me for comfort”); (b) involvement (8 items; e.g., “I teach my child how to play new games”); and (c) confidence (6 items; e.g., “I am confident in my parenting ability”). High scores on these sub-scales are indicative of a positive parenting relationship. Reliability was examined separately for the attachment, involvement and confidence subscales. For this study’s sample the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the attachment sub-scale were .73 for mothers and .79 for fathers, for the involvement sub-scale they were .88 for mothers and .82 for fathers, and for the parenting confidence sub-scale alpha coefficients were .66 for mothers and .71 for fathers.

Teacher–child relationships were assessed through the Portuguese version of the Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS, Cadima et al. 2013; Pianta 2001). STRS is a 28-items questionnaire that measures teachers’ perceptions over their relationship with the target child. This questionnaire has been extensively used in previous Portuguese research, showing adequate validity and reliability (Cadima et al. 2013, 2015). Items are rated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (definitely does not apply) to 5 (definitely applies). For this study, only the “closeness” sub-scale was used, measuring the degree of affection, warmth and open communication between the teacher and the child (7 items; e.g., “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with this child”). High scores on this sub-scale are indicative of a close teacher–child relationship. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this sample was .71.

Data Analyses

Missing values (.3 % of the total sample) were previously imputed using the expectation maximization algorithm (Dempster et al. 1977). For descriptive purposes, composite scores were then obtained by computing the mean of the items’ scores for each dimension.

We first conducted descriptive analyses and correlations of all the study variables: prosocial behavior, mother–, father– and teacher–child relationships. Next, using structural equation modeling (SEM) procedures, we tested our hypothesis by fitting a series of structural equations models to the data, applying full information maximum likelihood estimation (Enders 2001). All analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team 2013). Structural equation models were tested using the “lavaan” package (Rosseel 2012).

We used SEM with latent variables to account for measurement error in the questionnaires and to produce more accurate estimates. The following latent variables were considered: prosocial behavior, mother–, father– and teacher–child relationships. Prosocial behavior was represented by three manifest variables, namely the prosocial behavior subscale from the SDQ (Goodman 1997), as reported by mother, father and teacher. Reports from mother, father and teacher were combined to produce a more comprehensive indicator of children’s prosocial behavior. The use of different informants is advocated by the literature, considering that each informant may provide valuable information on children’s emotional and behavioral functioning (Renk 2005). By combining mother’s, father’s and teacher’s reports on a latent factor representing children’s prosocial behavior we were simultaneously accounting for the specificities (unique variance) and the commonalities (shared variance) of the distinct ratings. Latent variables representing the quality of mother– and father–child relationships were composed by three manifest variables, namely the attachment, involvement and confidence sub-scales from the PRQ (Kamphaus and Reynolds 2006). Due to the large number of items in the questionnaires and limited sample size, we used parcels as indicators of teacher–child relationship (three parcels) (Coffman and MacCallum 2005). Items were assigned to parcels using factor loadings as guide, following the procedure described by Little and Cunningham (2002).

Overall model fit was examined using the Chi square goodness-of-fit statistic, by considering Chi square to df ratio (Χ 2/df). Values below 2 are usually considered as an indicator of a good data-model fit (Schweizer 2010). Model fit was also evaluated through the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fix index (CFI) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Values lower than .05 for RMSEA and lower than .08 for SRMR indicate good model fit (Schweizer 2010). CFI values ranging from .90 to .95 and greater than .95 suggest acceptable and good fit, respectively (Schweizer 2010).

Research questions were addressed by fitting a structural equation model, testing the mediating role of the teacher–child relationship in the association between children’s relationships with their parents and prosocial behavior. Direct effects of children’s relationships with mother, father and teacher on children’s prosocial behavior were analyzed, as well as indirect effects of mother– and father–child relationships on children’s prosocial behavior, via the teacher–child relationship. The significance of each indirect effect was estimated using a bootstrapping procedure with 2000 resamples (Bollen and Stine 1990). Child age, child gender and both parents’ education levels were included as covariates, based on previous evidence suggesting age and gender effects on prosocial behavior as well as associations between family socioeconomic status and children’s prosocial behavior (Eisenberg et al. 2006). Child gender was dummy coded (0 = male; 1 = female). The same procedure was used to code mothers’ and fathers’ education level (0 = primary or secondary education; 1 = higher education).

Results

Preliminary data analysis revealed children from public (n = 48) and private (n = 120) preschools did not differ in prosocial behavior (t = .14, df = 166, p = .892), neither did they differ in the quality of their relationships with mother (t = .16, df = 166, p = .874), father (t = −.17, df = 166, p = .865) and teacher (t = 1.58, df = 166, p = .116). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc comparisons was conducted to examine differences among children with different levels of school attendance (less than 1 year, 1 year, 2 years and more than 3 years) in teacher–child relationship. Non-significant differences emerged between the groups in teacher–child relationship (F (3,150) = 1.12, p = .372). Also, there were no significant differences between children from one-child families (n = 90) and children from families with at least two children (n = 78), neither in terms of prosocial behavior (t = .94, df = 166, p = .347), nor in terms of the quality of their relationships with mother (t = 1.61, df = 166, p = .109), father (t = −.02, df = 166, p = .984) and teacher (t = −.09, df = 166, p = .928).

Pearson correlations and descriptive statistics for the study’s main variables and covariates are shown in Table 1. On average, parents and teachers reported “normal” levels in children’s prosocial behavior (M = 1.62, SD = .27), as defined by the SDQ’s authors (Goodman 1997). Mothers (M = 3.01, SD = .34) reported a higher quality of parent–child relationship than fathers (M = 2.87, SD = .35). Children’s relationships with teachers were characterized by relatively high levels of closeness (M = 4.34, SD = .53). The quality of children’s relationships with both parents and teacher were positively associated with children’s prosocial behavior, with moderate effect sizes (p < .001 for mother and teacher, p = .001 for fathers). A significant association was found between the quality of the mother–child relationship and the quality of the father–child relationship (r = .22, p = .004), as well as between mother–child relationship and teacher–child relationship (r = .23, p = .003). The association between father–child relationship and teacher–child relationship was non-significant (r = .09, p = .270). There was also a significant correlation between child age and prosocial behavior (r = .27, p < .001). Children’s gender, mother education and father education were unrelated to children’s prosocial behavior. Children’s gender and fathers’ education were positively associated with the quality of the teacher–child relationship.

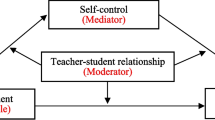

Figure 1 presents standardized coefficients for the hypothesized model. This model explained 58 % of variance in prosocial behavior, revealing acceptable fit (Schweizer 2010).

The associations between the child’s relationships and prosocial behavior were examined by considering the direct paths between mother–child relationship, father–child relationship, teacher–child relationship and prosocial behavior. Results showed a significant positive path between quality of father–child relationship and prosocial behavior (β = .33, p = .009), as well as between teacher–child relationship and prosocial behavior (β = .45, p = .001). The direct path between mother–child relationship and prosocial behavior was, however, non-significant (β = .18, p = .153).

Indirect paths between child relationships with parents and prosocial behavior, via teacher–child relationship, were examined to determine whether teacher–child relationship mediates the link between the child’s relationships with parents and prosocial behavior. The path between father–child relationship and teacher–child relationship was non-significant, supporting the rejection of the mediation hypothesis. However, paths between mother–child relationship, teacher–child relationship and prosocial behavior were significant. A bootstrapping procedure revealed a significant indirect effect of mother–child relationship on prosocial behavior, via teacher–child relationship (see Table 2). This result indicated that the association between mother–child relationship and prosocial behavior was mediated by teacher–child relationship.

Regarding the hypothesized covariates, children’s age was significantly linked to prosocial behavior with a moderate effect size (β = .33, p < .001). The remaining covariates (child gender and both parents’ education levels) were unrelated to prosocial behavior.

Discussion

The first goal of this study was to examine the contributions of mother–, father– and teacher–child relationships to children’s prosocial behavior. Three main findings emerged: (1) the father–child relationship was directly associated with child prosocial behavior; (2) the teacher–child relationship was directly associated with child prosocial behavior; (3) the association between the mother–child relationship and child prosocial behavior was non-significant. The second goal of the present study was to analyze whether the quality of the teacher–child relationship mediated the association between children’s relationships with their parents and prosocial behavior. We hypothesized that the quality of father– and mother–child relationships would be indirectly linked to child prosocial behavior, through the teacher–child relationship. Our findings did not support the mediating effect of the teacher–child relationship on the association between the father–child relationship and child prosocial behavior. Nevertheless, we found an indirect link between the mother–child relationship and prosocial behavior, through the teacher–child relationship.

One of the most interesting findings of the current study was that, unlike the mother–child relationship, the father–child relationship was directly linked to child prosocial behavior. Prior literature has suggested a consistent growth of fathers’ involvement in housework and childcare related tasks over the last decades (Yeung et al. 2001). This trend is stronger in dual earner-families in which parents share family tasks and responsibilities in a more egalitarian way (Bonney et al. 1999; Cabrera et al. 2000). Children who took part in this study were all from dual-earner families. Therefore, they may have benefited from high levels of fathers’ involvement in family daily routines. Fathers’ increasing involvement in family life, as well as their tendency to engage in play activity with the child (Yeung et al. 2001), may explain the significant contribution of the father–child relationship to children’s prosocial behavior. In fact, previous studies suggested play activity is a key component of fathers’ involvement (Bonney et al. 1999; McBride and Mills 1993). Fathers spend a large proportion of their time engaging in play activities with the child, whereas mothers spend more of their time in childcare activities (Bonney et al. 1999; McBride and Mills 1993). Compared to childcare activities, play activities are characterized by higher levels of parental responsiveness, compliance and shared positive affect (Lindsey et al. 2010). These specific features of parental engagement style have been associated with children’s prosocial behavior (Brophy-Herb et al. 2010; Clark and Ladd 2000; Lindsey et al. 2010). Therefore, the distinct types of parent–child activities may influence the association between the quality of the parent–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior, explaining differences between mothers’ and fathers’ contributions to children’s prosocial behavior. Further studies, however, are needed to clarify whether the link between the quality of the parent–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior is moderated by specific features of parental participation, namely by the type of parent–child activities. The notion of hierarchy of internal working models of attachment (Main et al. 1985) support an alternative explanation for the observed differences between the associations of mother–child and father–child relationships with children’s prosocial behaviors. Perhaps, the quality of the father–child relationship tends to directly affect children’s behavioral patterns, while the quality of the mother–child relationship may have a more structural impact on children’s socioemotional functioning. By providing the foremost internal working model of relationships, the mother–child relationship may have a major role in guiding children’s social interactions with other adults, namely fathers and teachers. Through this indirect pathway, the quality of the mother–child relationship may indelibly affect the distinct dimensions of children’s socioemotional development, including prosocial behavior. Further research, nonetheless, is required to confirm this hypothesis.

Our findings also emphasize the importance of the teacher–child relationship on children’s prosocial behavior. Children attending early childcare and educational settings spend a considerable amount of their time engaging in social interactions with peers and adults. Teachers play an important role in promoting positive social exchanges within the preschool classroom, namely by setting behavioral expectations and by shaping the children’s prosocial behavior during daily activities (Howes 2000; Myers and Morris 2009; Pianta and Stuhlman 2004; Spivak and Howes 2011). Even though our findings showed the teacher–child relationship to be significantly associated with children’s prosocial behavior, the association between mother–child relationships and children’s prosocial behavior was non-significant. This is consistent with previous studies, suggesting the quality of children’s relationship with their mothers was unrelated to prosocial behavior, when the effect of the teacher–child relationship is considered (Howes et al. 1994; Kienbaum et al. 2001; Mitchell-Copeland et al. 1997). In these previous studies, the absence of associations between the mother–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior was attributed to a context effect (Howes et al. 1994; Kienbaum et al. 2001; Mitchell-Copeland et al. 1997). As in previous studies, the current study failed to confirm a direct association between the mother–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior. However, this finding cannot be attributed to a context effect as our results were based on a multi-informant perspective of prosocial behavior, combining scores from mother, father and teacher. Therefore, the current study further clarifies the relative contributions of mother– and teacher–child relationships to prosocial behavior, suggesting that the absence of a direct link between the mother–child relationship and child prosocial behavior cannot be attributable to a context effect as was the case in previous studies (Howes et al. 1994; Kienbaum et al. 2001; Mitchell-Copeland et al. 1997).

Although the results from the current study revealed the direct association between the mother–child relationship and prosocial behavior was non-significant, the indirect association was found to be statistically significant. As anticipated, our results suggested the link between the quality of the mother–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior is mediated by the quality of the teacher–child relationship. This finding is in accordance with the theoretical assumption that children’s early relational experiences with significant caregivers contribute to the development of internal models of relationships that guide children’s social orientation in further relationships (Bowlby 1988; Main et al. 1985; Stayton et al. 1971; Waters et al. 1986). Children with secure attachment relationships are more likely to develop positive expectations towards social interactions, the sense of confidence to approach others and the social competence to maintain positive interactions within different social contexts (Hastings et al. 2007; Sroufe and Fleeson 1986). The present study provided evidence suggesting children who experience mother–child relationships of high quality are more likely to display closer teacher–child relationships, which in turn is associated with children’s prosocial behavior. These results underline the importance of considering the relations among relationships to better understand children’s prosocial behavior (Matos 2003).

Prosocial behavior is a central dimension of social competence linked to children’s social acceptance and psychological adjustment. This study adopted a multi-informant perspective on child prosocial behavior, extending previous literature by clarifying the complex interplay between mother–, father– and teacher–child relationships and its effects on prosocial behavior. Our findings point out some clues for practitioners working with children and their parents. By promoting close relationships with the children, characterized by warm interactions and open communication, preschool teachers may foster children’s prosocial behavior. In addition, our findings underline the unique contribution of mothers and fathers to children’s prosocial behavior, suggesting parental intervention efforts may focus on improving the quality of the parents–child relationship as a way to promote children’s prosocial behavior. There are, however, some limitations that should be noted: (1) our results were based on cross-sectional data, and thus with no possibility of causal inferences; (2) the data were only collected through adult self-report and some dimensions revealed less adequate internal consistency; (3) parents– and teacher–child relationships were measured through different indicators preventing comparisons between the contributions of each relationship to children’s prosocial behavior; (4) the sample size was relatively small, reducing the statistical power and reinforcing the need for caution regarding generalization of findings. Future studies addressing the link between children’s early relationships and prosocial behavior, would benefit from the adoption of longitudinal designs with data from more heterogeneous samples of children, collected through a multi-method approach combining parents’ and teachers’ reports with child direct assessment, home and preschool observations. Specifically, observation can be a useful methodology to capture important features of mother– and father–child interactions that may contribute to children’s prosocial behavior. These data would be helpful to clarify some of the current study’s findings, namely the absence of a direct link between the mother–child relationship and children’s prosocial behavior. Moreover, there is a lack of studies focusing on the interactive characteristics of the father–child involvement associated with children’s prosocial behavior.

References

Bollen, K., & Stine, R. (1990). Direct and indirect effects: Classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociological Methodology, 20, 115–140. doi:10.2307/271084.

Bonney, J., Kelley, M., & Levant, R. (1999). A model of fathers’ behavioural involvement in child care in dual-earner families. Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 401–415. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.13.3.401.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent–child attachment and healthy human development. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Brophy-Herb, H., Schiffman, R., Bocknek, E., Dupuis, S., Fitzgerald, H., Horodynski, M., et al. (2010). Toddlers’ social-emotional competence in the contexts of maternal emotion socialization and contingent responsiveness in a low-income sample. Social Development, 20(1), 73–92. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00570.x.

Bryant, B., & Crockenberg, S. (1980). Correlates and dimensions of prosocial behavior: A study of female siblings with their mothers. Child Development, 51(2), 529–544. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1980.tb02575.x.

Cabrera, N., Tamis-LeMonda, C., Bradley, R., Hofferth, S., & Lamb, M. (2000). Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Development, 71(1), 127–136. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00126.

Cadima, J., Doumen, S., Verschueren, K., & Leal, T. (2013). Examining teacher–child relationship quality across two countries. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology,. doi:10.1080/01443410.2013.864754.

Cadima, J., Verschueren, K., Leal, T., & Guedes, C. (2015). Classroom interactions, dyadic teacher–child relationships, and self–regulation in socially disadvantaged young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology,. doi:10.1007/s10802-015-0060-5.

Caprara, G., Barbaranelli, C., Pastorelli, C., Bandura, A., & Zimbardo, P. (2000). Prosocial foundations of children’s academic achievement. Psychological Science, 11(4), 302–306. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00260.

Carlo, G., Mestre, M., Samper, P., Tur, A., & Armenta, B. (2010). The longitudinal relations among dimensions of parenting styles, sympathy, prosocial moral reasoning, and prosocial behaviors. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(2), 116–124. doi:10.1177/0165025410375921.

Clark, K., & Ladd, G. (2000). Connectedness and autonomy support in parent-child relationships: Links to children’s socioemotional orientation and peer relationships. Developmental Psychology, 36(4), 485–498. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.36.4.485.

Coffman, D., & MacCallum, R. (2005). Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(2), 235–259. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr4002_4.

Dempster, A., Laird, N., & Rubin, D. (1977). Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 39(1), 1–38. doi:10.2307/2984875.

Denham, S. (1994). Mother–child emotional communication and preschoolers’ security of attachment and dependency. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 155(1), 119–121. doi:10.1080/00221325.1994.9914765.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R., & Spinrad, T. (2006). Prosocial development. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Social emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 646–718). New Jersey: Wiley.

Enders, C. K. (2001). The performance of the full information maximum likelihood estimator in multiple regression models with missing data. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61(5), 713–740. doi:10.1177/0013164401615001.

Garner, P. (2006). Prediction of prosocial and emotional competence from maternal behavior in African American preschoolers. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12(2), 179–198. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.12.2.179.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 38, 581–586.

Gottfried, A., Gottfried, A., & Bathurst, K. (2002). Maternal and dual-earner employment status and parenting. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Volume 2): Biology and ecology of parenting (pp. 207–228). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hallers-Haalboom, E. T., Mesman, J., Groeneveld, M. G., Endendijk, J. J., van Berkel, S. R., van der Pol, L. D., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2014). Mothers, fathers, sons and daughters: Parental sensitivity in families with two children. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(2), 138–147. doi:10.1037/a0036004.

Hastings, P., Utendale, W., & Sullivan, C. (2007). The socialization of prosocial development. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 638–664). New York: Guilford Press.

Hay, D., & Pawlby, S. (2003). Prosocial development in relation to children’s and mothers’ psychological problems. Child Development, 74(5), 1314–1327. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00609.

Hay, D., Payne, A., & Chadwick, A. (2004). Peer relations in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 45(1), 84–108. doi:10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00308.x.

Howes, C. (2000). Social-emotional classroom climate in child care, child–teacher relationships and children’s second grade peer relations. Social Development, 9(2), 191–204. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00119.

Howes, C., & Matheson, C. (1992). Contextual constraints on the concordance of mother–child and teacher–child relationship. In R. Pianta (Ed.), New directions for child development: Beyond the parent: The role of other adults in children’s lives (pp. 25–40). San-Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Howes, C., Matheson, C., & Hamilton, C. (1994). Maternal, teacher, and child care history correlates of children’s relationships with peers. Child Development, 65, 264–273. doi:10.2307/1131380.

INE. (2011). Censos 2011. [2011 National Census]. Retrieved March 26, 2014, from http://censos.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=CENSOS&xpgid=censos2011_apresentacao

Kamphaus, R., & Reynolds, C. (2006). Parenting relationship questionnaire. Minneapolis: NCS Pearson.

Kärtner, J., Keller, H., & Chaudhary, N. (2010). Cognitive and social influences on early prosocial behavior in two sociocultural contexts. Developmental Psychology, 46(4), 905–914. doi:10.1037/a0019718.

Kestenbaum, R., Farber, E., & Sroufe, L. (1989). Individual differences in empathy among preschoolers: Relation to attachment history. New Directions for Child Development, 44, 51–64. doi:10.1002/cd.23219894405.

Kiang, L., Moreno, A., & Robinson, J. (2004). Maternal preconceptions about parenting predict child temperament, maternal sensitivity, and children’s empathy. Developmental Psychology, 40(6), 1081–1092. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1081.

Kienbaum, J., Volland, C., & Ulich, D. (2001). Sympathy in the context of mother-child and teacher-child relationships. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25(4), 302–309. doi:10.1080/01650250143000076.

Koestner, R., Franz, C., & Weinberger, J. (1990). The family origins of empathic concern: A 26-year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 709–717. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.709.

Lewis, C., & Lamb, M. (2003). Fathers’ influences on children’s development. The evidence from two-parent families. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 18, 211–228. doi:10.1007/BF03173485.

Lindsey, E., Caldera, Y., & Rivera, M. (2013). Mother-child and father-child emotional expressiveness in Mexican-American families and toddlers’ peer interactions. Early Child Development and Care, 183, 378–393. doi:10.1080/03004430.2012.711589.

Lindsey, E., Cremeens, P., & Caldera, Y. (2010). Mother–child and father–child mutuality in two contexts: Consequences for young children’s peer relationships. Infant and Child Development, 19, 142–160. doi:10.1002/icd.

Little, T., & Cunningham, W. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1.

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, 66–104. doi:10.2307/3333827.

Marzocchi, G. M., Capron, C., Di Pietro, M., Duran Tauleria, E., Duyme, M., Frigerio, A., et al. (2004). The use of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in Southern European countries. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 13(2004), 40–46. doi:10.1007/s00787-004-2007-1.

Matos, P. M. (2003). O conflito à luz da teoria da vinculação [An attachment theory perspective to conflict]. In M. E. Costa (Ed.), Gestão de conflitos na escola [Managing conflict at school] (pp. 143–191). Lisboa: Universidade Aberta.

McBride, B., & Mills, G. (1993). A comparison of mother and father involvement with their preschool age children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 8, 457–477. doi:10.1080/03004430.2012.711596.

Mitchell-Copeland, J., Denham, S., & Demulder, E. (1997). Q-sort assessment of child–teacher attachment relationships and social competence in the preschool. Early Education and Development, 8(1), 27–39. doi:10.1207/s15566935eed0801.

Myers, S., & Morris, A. (2009). Examining associations between effortful control and teacher-child relationships in relation to head start children’s socioemotional adjustment. Early Education and Development, 20(5), 756–774. doi:10.1080/10409280802571244.

O’Connor, E., & McCartney, K. (2006). Testing associations between young children’s relationships with mothers and teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 87–98. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.87.

Parke, R. (2002). Fathers and families. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol 3. Being and becoming a parent (2nd ed., pp. 27–73). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pianta, R. (2001). Student–teacher relationship scale: Professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Pianta, R., Hamre, B., & Stuhlman, M. (2003). Relationships between teachers and children. In W. Reynolds & G. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (Vol 7): Educational psychology (pp. 199–234). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Pianta, R., & Stuhlman, M. (2004). Teacher–child relationships and children’s success in the first years of school. School Psychology Review, 33(3), 444–458.

R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Renk, K. (2005). Cross-informant ratings of the behavior of children and adolescents: The “gold standard”. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(4), 457–468. doi:10.1007/s10826-005-7182-2.

Roopnarine, J., Fouts, H., Lamb, M., & Lewis-Elligan, T. (2005). Mothers’ and fathers’ behaviors toward their 3- to 4-month-old infants in lower, middle, and upper socioeconomic African American families. Developmental Psychology, 41(5), 723–732. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.723.

Roorda, D., Verschueren, K., Vancraeyveldt, C., Craeyevelt, S. Van, & Colpin, H. (2014). Teacher–child relationships and behavioral adjustment: Transactional links for preschool boys at risk. Journal of School Psychology, 52(5), 495–510. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2014.06.004.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36.

Sabol, T., & Pianta, R. (2012). Recent trends in research on teacher-child relationships. Attachment and Human Development, 14(3), 213–231. doi:10.1080/14616734.2012.672262.

Schweizer, K. (2010). Some guidelines concerning the modeling of traits and abilities in test construction. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 1–2. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000001.

Sebanc, A. (2003). The friendship features of preschool children: Links with prosocial behavior and aggression. Social Development, 12(2), 249–268. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00232.

Spivak, A., & Howes, C. (2011). Social and relational factors in early education and prosocial actions of children of diverse ethnocultural communities. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 57(1), 1–24. doi:10.1353/mpq.2011.0002.

Sroufe, L., & Fleeson, J. (1986). Attachment and the construction of relationships. In W. Hartup & Z. Rubin (Eds.), Relationships and development (pp. 51–72). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Staub, E. (1992). The origins of caring, helping, and nonaggression: Parental socialization, the family system, schools, and cultural influence. In P. Oliner, L. Baron, L. Blum, D. Krebs, & M. Smolenska (Eds.), Embracing the other: Philosophical, psychological, and historical perspectives on altruism (pp. 390–412). New York, NY: New York University Press.

Stayton, D., Hogan, R., & Ainsworth, M. (1971). Infant obedience and maternal behavior: The origins of socialization reconsidered. Child Development, 42, 1057–1069. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1971.tb02002.x.

Stone, L., Otten, R., Engels, R., Vermulst, A., & Janssens, J. (2010). Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for 4- to 12-year-olds: A review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13(3), 254–274. doi:10.1007/s10567-010-0071-2.

Vieira, J. M., Cadima, J., Leal, T., & Matos, P. M. (2013). Validation of a Portuguese version of the Parenting Relationship Questionnaire. In Poster session presented at the meeting of the 16th European Conference on Developmental Psychology (ECDP). Lausanne, Switzerland.

Waters, E., Hay, D., & Richters, J. (1986). Infant–parent attachment and the origins of prosocial and antisocial behavior. In D. Olweus, J. Block, & M. Radke-Yarrow (Eds.), Development of antisocial and prosocial behavior: Research, theories, and issues (pp. 97–125). Orlando, Fl: Weissbrod Academic Press.

Woerner, W., Fleitlich-Bilyk, B., Martinussen, R., Fletcher, J., Cucchiaro, G., Dalgalarrondo, P., et al. (2004). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire overseas: evaluations and applications of the SDQ beyond Europe. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 13, 47–54. doi:10.1007/s00787-004-2008-0.

Yeung, J., Sandberg, J., Davis-Kean, P., & Hofferth, S. (2001). Children’s time with fathers in intact families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63, 136–154. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00136.x.

Zahn-Waxler, C., Radke-Yarrow, M., Wagner, E., & Chapman, M. (1992). Development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 28(1), 126–136. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.28.1.126.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by FEDER, COMPETE program, and by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, PTDC/MHC-CED/5218/2012 Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreira, T., Cadima, J., Matias, M. et al. Preschool Children’s Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Mother–Child, Father–Child and Teacher–Child Relationships. J Child Fam Stud 25, 1829–1839 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0369-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0369-x