Abstract

We systematically reviewed the evidence for the efficacy and effectiveness of brief parenting interventions, defined as <8 sessions in duration, in reducing child externalizing behaviors. While there is significant evidence to support the efficacy of parenting interventions of 8–12 sessions in duration, the public health benefit of these interventions is limited by low participation rates, high attrition rates and the lack of implementation by a wide range of practitioners. Brief parenting interventions have the potential to extend the reach and impact of parenting interventions and steer children away from a trajectory of life course persistent behavior problems. A search of four electronic databases was undertaken to identify RCTs conducted on brief parenting interventions. The primary outcome was child externalizing behaviors and secondary outcomes included parenting skills, parental self-efficacy, parental mental health and partner relationship functioning. The heterogeneity of included studies prevented a meta-analysis but characteristics of the studies were described. Nine papers summarising the results of eight studies with 836 families in five countries met inclusion criteria. All studies found significant improvements in parent-rated child externalizing behaviors, parenting skills and parenting self-efficacy, relative to control or comparison groups, with findings maintained at follow-up. Less consistent findings emerged for parental mental health and partner relationship functioning. This review provides initial evidence that brief parenting interventions may be sufficient to reduce child externalizing behavior problems for some families, however further research is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevalence estimates of childhood mental health problems worldwide vary widely between 5 and 26 % (Brauner and Stephens 2006) with recent estimates in the US of approximately 18 % (Houtrow and Okumura 2011). Childhood mental health problems are often separated into internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Externalizing problems describe behavior that is characterised by aggression, defiance, hostility and poor impulse control and these behaviors are the main reason for referral to child and adolescent mental health services (Kazdin 2008). While for some young children, externalizing behaviors are transient and limited to a specific development stage; for many, however, the behaviors persist throughout childhood and place them at risk of long-term outcomes that are significant and costly to society (e.g., Colman et al. 2009; Fergusson et al. 2005).

There is significant evidence from the past 30 years that parenting interventions based on social learning and cognitive-behavior theory such as Triple P-Positive Parenting Program (Sanders 1999), Incredible Years (Webster-Stratton and Reid 2003), Parent Management Training Oregon Model (PMTO; Patterson et al. 2002) and Parent Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT; Eyberg et al. 1995) are effective in changing dysfunctional parenting and in improving children’s externalizing problems in the short- and longer-term (de Graaf et al. 2008a, b; Nowak and Heinrichs 2008; Eyberg et al. 2008; Thomas and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007). However, there are low participation rates (Heinrichs et al. 2005) and high attrition rates (up to 60 %, Kazdin 1996; Nowak and Heinrichs 2008) which limit the reach and impact of parenting interventions. Low uptake rates and high attrition rates may be due to the demands of participation in typical individual or group parenting interventions, which are usually 8–12 sessions in duration (Bradley et al. 2003; Lavigne et al. 2008), but can be as many as 24 sessions.

Lengthy parenting interventions are not only challenging for parents to attend in terms of organising childcare, transport and competing family priorities (Kazdin and Wassell 1999), but they are also resource-intensive, costly and require significant clinician time through training and supervision (O’Brien and Daley 2011). According to the RE-AIM framework, the impact of the intervention is a function of five factors: Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (Glasgow et al. 1999). This means that as well as reach and efficacy, interventions need to be adopted, implemented and maintained over time by a variety of health care professionals in a range of settings. Primary care practitioners such as child health nurses and general practitioners are often best placed to provide interventions to families with young children with externalizing behavior problems, but the length of typical parenting interventions and the training and supervision requirements are a significant barrier for implementation.

There is growing recognition that in order to radically extend the reach of parenting interventions and impact on the prevalence of child externalizing problems, a range of flexible ‘low intensity’ or ‘light touch’ interventions are required (Sanders and Kirby 2010). Low intensity interventions include brief individual or group interventions as well as self-directed interventions, where parents work through the materials on their own with minimal or no therapist assistance. These can be offered as the first step as part of a stepped-care approach, with more intensive interventions offered to those who require more support (Haaga 2000). However, in order for stepped care approaches to be effective, low intensity interventions have to produce equivalent outcomes to more intensive interventions for at least proportion of participants (Bower and Gilbody 2005). There is increasing research on self-directed parenting programs, where parents work through the materials on their own with little or no therapist support, and a recent meta-analysis found that they result in similar outcomes compared with therapist-led interventions (Tarver et al. 2014). While self-directed programs are low intensity, they are not always brief in duration, so still may be burdensome for families. Therefore, brief individual or group interventions are required for families who would prefer brief therapist support over a longer self-directed or therapist-led program, and also to enable delivery by primary care practitioners.

Brief interventions aim to condense the key components of effective parenting programs into a shorter program length. While there is no accepted definition of what a ‘brief’ parenting intervention constitutes, since many parenting programs are between 8 and 12 sessions (Bradley et al. 2003; Lavigne et al. 2008), ‘brief’ can be defined as <8 sessions in duration. Supporting this definition, research on psychological interventions for adult mental health disorders such as depression has also defined brief interventions as <8 sessions in duration (e.g., Nieuwsma et al. 2011). There already appears to be a trend towards implementing brief interventions in publicly funded child and adolescent mental health services, in order to cope with the excessive demand for services (Perkins 2006). While the efficacy of ‘moderately intensive’ parenting programs of 8–12 sessions has already been established (Lavigne et al. 2008), it is now a priority to examine the effects of brief parenting interventions in reducing child externalizing behavior problems and in improving parent and family functioning. The aim of this systematic review is to assess the evidence for the efficacy and effectiveness of brief (<8 sessions) individual or group parenting interventions for reducing child externalizing behavior problems.

Method

Inclusion Criteria

Participants will be caregivers of children aged 2–8 years who have either been diagnosed with Oppositional Defiant Disorder; have elevated externalizing behaviors; who are at risk of having elevated externalizing behaviors as a consequence of presence of a family risk factor (e.g., parental depression); or caregivers who are concerned about their child’s behavior. Thus, studies that use selected and targeted interventions for child externalizing behaviors will be included, but universal interventions that target an entire population with the aim of preventing problems will not be included. Studies that target children with ADHD, medical health problems, and developmental delays or disabilities will not be included. Studies including children younger than 2 or older than 8 years will be included in the review if the mean child age falls within the 2–8 year age range. This age range was selected since there is evidence that parenting interventions are less efficacious with parents of children over 8 years (e.g., Ogden and Hagen 2008).

The review will include randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compare brief interventions with a control or comparison group such as a waitlist control group, no interventions or treatment as usual. The articles need to be published in English between 1992 and May 2015.

Parenting interventions of <8 sessions, delivered in individual, group or telephone-assisted format will be included. Parenting interventions should be based on social learning theories since these interventions have substantial research to support their efficacy (Chorpita et al. 2011) and focus on modifying parenting skills in order to reduce child externalizing behaviors. Studies that report on interventions with self-directed sessions will be excluded (since reviews already exist on self-directed interventions) as will studies that examine multi-component interventions that include parenting interventions as only one component of the intervention.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was measures of child externalizing behaviors. Secondary outcomes include: (1) parenting skills, practices or discipline style, (2) parental self-efficacy, competence, confidence or satisfaction, (3) parental mental health and (4) parental relationship functioning (satisfaction or conflict).

Search Strategy

Keyword searches of the following electronic databases were undertaken: PsychINFO, Medline, Sociological Abstracts, Web of Science. There were two groups of search terms. The first group related to the intervention and included the terms: parent intervention, parent training, parenting program, behavioral family therapy, parent support and positive parenting. The second group of search terms related to child behavior and included the terms: behavior problems, disruptive behavior, externalizing behavior, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, aggression and child mental health.

Study Selection

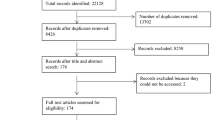

The initial literature search yielded 4061 articles. Article titles were screened for eligibility by the first author (LT) and the second author (CH) screened a random sample of 622 titles (15 %) with agreement of 96 %. Where agreement was not reached, the abstract for the article was reviewed by both authors. From the title search, 189 articles were selected for an abstract review by the first author with the second author reviewing a random sample of 88 abstracts (47 %) with agreement of 91 %. Again, where agreement was not reached between reviewers, the full article was reviewed by both authors. As many abstracts did not include information about the duration of the intervention, this necessitated a review of the full article to determine eligibility. In total, 64 articles were selected for full review by both authors independently with nine meeting inclusion criteria. These nine papers described the results from eight studies. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of article selection, including reasons for exclusion.

Data Extraction, Coding and Quality Assessment

For the nine articles describing eight studies, information was independently abstracted from both authors on study sample, recruitment and inclusion criteria; intervention; design of study and retention rate; timing of measurement; targeted outcomes and measures; and results including statistical significance, effect size and clinical significance. The articles were also independently reviewed for quality using a modified version of the Quality Index (Downs and Black 1998), a valid and reliable tool for measuring methodological quality. The original 27-item Quality Index was modified to exclude 4 items that were not relevant including 2 items about blinding, 1 about allocation concealment and 1 about adverse events. These items were excluded as they are not relevant to studies of parenting interventions since it is not possible to conceal allocation from participant or blind them to condition, and adverse events are usually not reported in these studies. The remaining 23 items assessed: 9 items on reporting of the study (e.g., were the interventions clearly described?), 3 items on external validity (e.g., were subjects who were prepared to participate representative of the entire population from which they were recruited?), 10 items on internal validity (e.g., were the main outcome measures accurate—valid and reliable?); and 1 item on power. Each checklist item was scored 0 (no/unable to determine) or 1 (yes) with a maximum possible score of 23. The two reviewers resolved disagreements regarding quality assessment through discussion.

Table 1 summarises the abstracted information from the nine articles and the Quality Index Score. Where statistical analyses were conducted with MANOVAs, the results in Table 1 include only the findings of the ANOVAs where MANOVAs were significant. Only outcomes relevant to the focus of this review are reported in the table. Due to the small number of papers identified and significant variations in interventions, child age, settings and outcomes, a formal meta-analysis was not conducted.

Results

Participant Characteristics

All studies recruited parents of children who had concerns or were seeking help about their child’s behavior. The focus was on parents of children in the pre-school or early primary school age range, with the exception of Kjøbli and Odgen (2012) and Meija et al. (2015) who recruited parents of 3–12 year olds. Joachim et al. (2010) recruited parents who were concerned about problems on shopping trips while Morawska et al. (2011) and Dittman et al. (2015) recruited parents who were concerned about child disobedience and Bradley et al. (2003) and Meija et al. (2015) recruited parents having trouble managing their child’s behavior. For this latter study, children had to score above the mean on the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Eyberg and Pincus 1999). Studies predominantly recruited families via community advertising except for Kjøbli and Odgen (2012) and Turner and Sanders (2006) who recruited parents of children seeking help from a primary care agency and Meija et al. (2015) who recruited parents from schools in disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

Types of Interventions

Of the eight studies, six used the Triple P system of intervention (Sanders 1999). Triple P includes a tiered system of support that increases in intensity from a universal communication strategy (Level 1), brief low-intensity seminars, individual or group programs (Levels 2 and 3) to more intensive group and individual programs (Level 4 and 5). Triple P uses a self-regulatory framework where parents are taught parenting skills and strategies to become independent problem solvers. Level 3 includes information and advice for parents as well as active skills training (DVD modelling of skills, roleplay, rehearsal, feedback and group discussion). Five of the studies examined the efficacy of different Triple P Discussion Groups (“Dealing with Disobedience”, “Hassle-free Shopping” and “Hassle Free Mealtimes”). These 2-h Triple P Discussion Group, are a Level 3 intervention specifically designed for parents of children with discrete behavior problems. Morawska et al. (2011) and Meija et al. (2015) examined the “Dealing with Disobedience” program plus two telephone sessions while Dittman et al. (2015) examined the group program only. Joachim et al. (2010) examined “Hassle free Shopping” group program and Morawska et al. (2014) examined “Hassle-free Mealtimes” group program. Meija et al. (2015) minimally adapted the “Dealing with Disobedience” group intervention for Spanish speaking parents by using language translation and included two phone sessions.

The final study to examine Triple P was an effectiveness study in which child health nurses delivered the Primary Care Triple P (also a Level 3 intervention) with three to four (30 min) individual sessions (Turner and Sanders 2006). All of the studies were conducted in Australia with the exception of Dittman et al. (2015) who recruited families from New Zealand as well as Australia and Meija et al. (2015) who conducted the study in Panama City. Kjøbli and Odgen (2012) examined a brief version of PMTO lasting 3–5 individual sessions in an effectiveness study in Norway where the intervention was delivered by primary care practitioners. PMTO is similar to Triple P in that it aims to enhance parenting skills which are taught through active skills training including roleplay and problem solving discussions. The final study was also an effectiveness study of a psychoeducational parenting intervention which involved four 2-h group sessions using the videotape from the 123 Magic Program and was delivered in community agencies by community facilitators in Canada (Bradley et al. 2003). The intervention included video demonstrations of skills, group discussion and covered key parenting strategies such as timeout and rewards although it was not specified whether active skills training such as roleplay and rehearsal were included in this program.

Outcomes

Morawska et al. (2011) and Dittman et al. (2015) found the Triple P Parent Discussion Group for Dealing with Disobedience resulted in significantly lower parent-rated child behavior problems at post-assessment when compared with waitlist, with large effect sizes and changes maintained at 6 month follow-up for the intervention group. Similarly, the intervention groups in both studies had significantly lower dysfunctional parenting and higher parenting efficacy at post-assessment with moderate to large effect sizes, and improvements maintained at follow-up. The intervention groups also showed more clinically significant change and reliable change across most measures of child behavior, dysfunctional parenting and parenting efficacy at post-assessment than waitlist (see Table 1). No significant group differences emerged for the measure of parental mental health or parental relationship functioning at post (Dittman et al. 2015) but Morawska et al. (2011) found the intervention group was significantly higher than waitlist on partner support with small effects and changes maintained at follow-up. Attrition rates for the intervention group at post were 27 % (Dittman et al. 2015) and 18 % (Morawska et al. 2011).

Meija et al. (2015) found the same intervention resulted in significantly lower parent-rated child behavior problems at post, 3 and 6 month follow-up relative to a no intervention control, with moderate to large effect sizes (apart from one measure of child behavior at post, which only showed a small effect size). The effects of the intervention increased over time. The intervention group also showed significantly lower levels of dysfunctional parenting and mental health problems than the control across all three time points, with small to moderate effect sizes. The attrition rate for the intervention group at post-assessment was 11 %.

Joachim et al. (2010) found a similar pattern of findings for the Parent Discussion Group which focussed on problems with shopping. The intervention group had significantly fewer child behavior problems, less dysfunctional parenting and greater parenting efficacy than the waitlist control group at post-assessment with moderate to large effect sizes. No significant group differences in parental mental health emerged. The improvements in child behavior and parenting efficacy but not parenting were maintained at 6 month follow-up for the intervention group. A greater proportion of children in the intervention group were in the non-clinical range on one out of two measures of child externalizing behavior as well as for dysfunctional parenting and parental efficacy when compared with waitlist. Greater reliable change was found for one out of two measures of child behavior and parenting efficacy at post-assessment, but not for dysfunctional parenting. The attrition rate for the intervention group was 15 % at post.

Focussing on problems at mealtimes, Morawska et al. (2014) found the Parent Discussion Group resulted in significantly reduced frequency of child mealtime difficulties relative to the waitlist control at post-assessment, with large effects, but there were no significant group differences for three other measures of child behavior. Significant group differences were also found for one out of two measures of parenting and both measures of confidence/self-efficacy, with large effects. All improvements were maintained at follow-up for the intervention group. The intervention group showed significantly more reliable change on one out of two measures of child behavior, parenting and parenting confidence. The attrition rate was 18 % for the intervention group at post.

Turner and Sanders (2006) found Primary Care Triple P resulted in significantly fewer child behavior problems compared with the waitlist group on two out of six measures of child behavior, with large effect sizes and improvements maintained at follow-up. At post-assessment, 7.7 % of children in the intervention group were in the clinical range versus 61.5 % in waitlist. The intervention group had significantly lower ratings of dysfunctional parenting, parental anxiety and stress (but not depression) and higher ratings of parenting satisfaction (but not efficacy) at post compared with waitlist, with improvements maintained at follow-up for all measures except laxness, anxiety and stress. This study also included a 15 min observational parent–child interaction task that was coded for child and parent aversive behavior and no group differences in parent or child behavior emerged. The intervention group had 19 % attrition at post.

Kjøbli and Odgen (2012) and Kjøbli and Bjørnebekk (2013) found parents who received a brief version of PMTO rated children as having significantly fewer behavior problems compared with a treatment-as-usual comparison group at post-assessment and 6 month follow-up, with small to moderate effect sizes. This study also included teacher reports of child behavior but no significant group differences were found. The intervention group reported increased positive parenting, and reduced harsh discipline at post-assessment and follow-up when compared with the comparison group, with large effect sizes at post-assessment which were low to medium at follow-up. Significant group differences were found for post-assessment but not follow-up for harsh discipline for age and inconsistent discipline, but there were no significant differences at post or follow-up for appropriate discipline or clear expectations. There were no significant group differences in ratings of parental mental health at post-assessment, but differences approached significance by 6 month follow-up. There was 12 % attrition at post for the intervention group.

Bradley et al. (2003) found that families who received a brief psychoeducational parenting intervention reported less child problem behavior problems when compared with waitlist on two out of three measures at post-assessment, with small effect sizes (effect sizes were reported separately for experimental and control conditions). Improvements were maintained for a subsample (fewer than one-third of the intervention group) who returned questionnaires at one-year follow up. This subsample had higher scores on dysfunctional parenting at pre-assessment. The intervention group also reported significantly lower dysfunctional parenting and parental hostility than waitlist at post-assessment with improvements again maintained at follow-up. The attrition rate for the intervention group was 9 % at post.

Quality of Included Studies

The total mean score on the modified Quality Index (Downs and Black 1998) was 16.8 out of 23 (range 14–20). The mean subscale scores were 8.3/9 for reporting (range 7–9), 8.2/10 for internal validity (range 7–10) and 0.3/3 for external validity (range 0–1). Only two studies reported sufficient details of a formal power calculation (Meija et al. 2015; Morawska et al. 2014); the rest scored 0/1 on this subscale.

Discussion

Despite the large body of research on parenting interventions over the past 30 years, this systematic review identified only identified nine articles describing eight studies on brief parenting interventions that met inclusion criteria. Most of these studies were conducted in the last few years, despite the literature search spanning more than a 20 year period. This is surprising and indicates that it is a topic that requires more research, especially given that brief interventions may already be being delivered in clinical practice (Perkins 2006). However, the findings from these nine studies are promising and suggest that brief parenting interventions may be effective in reducing child externalizing behaviors and dysfunctional parenting for parents seeking help for emerging problem behaviors in their young children across a range of settings and problem behaviors. Across all studies there were significant group differences in parent reported externalizing behavior at post-assessment relative to the control/comparison group with changes maintained at follow-up. The findings for dysfunctional parenting showed a similar pattern with significant reductions at post-assessment which were maintained at follow-up in all but one study (Joachim et al. 2010). Similarly, studies that included a measure of parental self-efficacy or satisfaction found significant group differences on this measure.

For this review, brief interventions were defined as <8 sessions in duration, but the interventions in the included studies were very brief ranging from 1 session (2 h duration) to four sessions (8 h duration). Despite being very brief, large effects sizes for group differences in child externalizing behavior were found for studies on Triple P Discussion Groups and Primary Care Triple P (Dittman et al. 2015, Joachim et al. 2010; Morawska et al. 2011; Morawska et al. 2014; Turner and Sanders 2006) with smaller effects in for the studies on the psychoeducational parenting intervention and PMTO (Bradley et al. 2003; Kjøbli and Odgen 2012). Smaller effects were also found for the study examining a Triple P Discussion Group in Panama (Meija et al. 2015). It should be noted that the two studies that used either an active control group (Kjøbli and Odgen 2012) or a no intervention control (Meija et al. 2015) found smaller effect sizes than those using waitlist. It is now established that waitlist control groups result in larger effects than other control or comparison groups including no intervention controls (e.g., Furukawa et al. 2014) which highlights the need to use alternatives to waitlist control groups.

The improvements in measures of child behavior, parenting and parenting efficacy at post-assessment were largely maintained at follow-up. However, as the waitlist control design used by most studies did not include a control group at follow-up, the longer term effects of the intervention could not be thoroughly assessed in all but two studies. For Kjøbli and Bjørnebekk (2013) the effects of the intervention diminished over time but for Meija et al. (2015) the effects of the intervention strengthened over time relative to the no intervention control. Given the brief nature of the intervention, efficacy may be enhanced with a booster session delivered some weeks or months after the intervention. Bradley et al. (2003) was the only study to include a booster session which was delivered 4 weeks after the final session (before post), but this did not result in larger effects compared with the other studies. It is imperative that future research use control or comparison groups to enable the longer term effects of the intervention to be thoroughly assessed.

Taken together, these findings suggest brief parenting interventions may be sufficient to modify dysfunctional parenting and in turn reduce emerging child behavior problems, at least for some families. It should be noted, however, that significant intervention effects did not always emerge across all measures in each study. For example, Turner and Sanders (2006) found significant group differences on only 2 out of 6 child outcomes and Morawska et al. (2014) found differences on one out of four child outcomes. While relatively consistent findings were seen for child externalizing behavior and parenting, there were less consistent findings for measures of mental health and parental relationship functioning. Six out of eight studies included a measure of parental mental health, and significant group differences were only identified for three studies (Bradley et al. 2003; Meija et al. 2015; Turner and Sanders 2006). For the three studies that used a measure of relationship functioning, only one found significant group differences (Morawska et al. 2011). Participants in some studies may have scored low on these measures at pre-assessment, causing a floor effect, as was noted by Joachim et al. (2010). However, it is also possible that brief interventions may be insufficient to modify more distal family risk factors. It is important to note that research has found that a brief flexible parenting intervention that addressed family risk (but did not meet inclusion criteria for this study) led to reductions in child behavior regardless of levels of maternal depression (Gardner et al. 2009), suggesting that changes in these family risk variables may not be necessary to achieve changes in child outcomes in a brief intervention.

The attrition rates for the intervention groups across studies ranged from 9 to 27 % (average of 16 %). A review of 55 studies of more intensive formats of Triple P found attrition rates in the intervention groups to vary widely from 0 to 60 % with an average of 19 % (Nowak and Heinrichs 2008), which was not greatly different to that found in the present review. One of the key benefits expected of brief interventions is the lower attrition rates, due to the fewer demands made of families, so further research is needed to quantify the attrition rates and to determine whether they are significantly lower than more intensive interventions.

Overall, the quality ratings for included studies were adequate, although higher scores were obtained for the reporting and internal validity subscales than for the external validity subscale. In relation to external validity, most studies included in this review used community outreach campaigns to recruit families, so they were not able to address the issue of representativeness. Wilson et al. (2012) hypothesised that self-referred families may be more motivated and compliant when compared with most families in the population leading to a better than average response to intervention. The two effectiveness studies which did not rely on self-referred families also failed to include information about representativeness of the sample (that is, the characteristics of families who chose not to participate). Thus, families included in these studies may not be representative of families in the population eligible to participate and as such, the findings may overstate the impact of brief parenting interventions. It is difficult to report representativeness of self-referred parents as information is not usually available on the characteristics of parents who do not participate. However, reporting on sample representativeness may be possible when subjects are drawn from a specific population (e.g., clinical referred families) and future research should report this when possible. In relation to internal validity, only half of the studies reported sufficient information on treatment fidelity (see Table 1), so for the remaining studies it is not possible to determine whether the interventions were delivered as intended.

All included studies relied on parent-reports of child behavior from one parent (usually the mother, although this was not specified in all studies). Where teacher reports (Kjøbli and Bjørnebekk 2013; Kjøbli and Odgen 2012) and observational measures (Turner and Sanders 2006) were used, results regarding child behavior were non-significant although this may have been due to a floor effect for the observational measures. Thus, there is currently no evidence from any independent measure that brief parenting interventions result in reductions in child externalising behavior. Due to the potential biases of parent-report data, it is important to include independent measures of child behavior such as observational data. Also lacking from the studies reviewed was father ratings on measures as well as information about fathers’ involvement in the interventions and recent reviews have highlighted the importance of reporting this information (e.g., Fletcher et al. 2011; Smith et al. 2012; Tiano and McNeil 2005). In addition, no study compared a brief with a longer parenting intervention to demonstrate equivalence and, according to Bower and Gilbody (2005), this is critical in order to support a stepped-care model of service delivery. All studies recruited parents of children concerned about or seeking help for their child’s behavior and none included children who were diagnosed with ODD or in the clinical range for child behavior problems (although just over half of Kjøbli and Ogden’s sample were in the clinical range) so the effects of brief parenting interventions for parents of children with more severe externalizing behaviors are unknown. It may be that brief parenting interventions are best suited towards families at low to moderate level of difficulty (Sanders 2008). However, since there is some evidence that they are already being implemented in child mental health services (Perkins 2006), examining efficacy with parents of children at higher levels of difficulty may be warranted. Clearly, not all families will benefit from a brief intervention and future research should aim to examine the moderators or predictors of outcome. Even if brief interventions are only effective with a small proportion of families, their ease of dissemination and low cost may mean that they are worthwhile alternative to more intensive interventions (Kazdin 2008). Future research should also aim to examine which strategies contribute to the efficacy of parenting programs more generally so these can be included in brief parenting interventions. Leijten et al. (2015) highlighted the importance of conducting randomized microtrials to test the efficacy of discrete parenting strategies, and this is a priority to maximise the efficacy of brief interventions.

Limitation of This Review

The key limitation of this review was the inability to conduct a meta-analysis due the heterogeneity of included studies, which meant the strength of the effects of brief parenting interventions could not be quantified. In addition, the restricted focus of the review meant that some articles on brief interventions were not included. For example, articles on the Family Check Up intervention (e.g., Dishion et al. 2008) were not included since it was deemed a multicomponent intervention of which parent training was one component. Similarly, studies of brief interventions focussing on certain populations, such as children with birth complications (Schappin et al. 2013) were also not included, nor were brief interventions examined through study designs that were not RCTs (Axelrad et al. 2013). Thus, the narrow focus of the review may have impacted on the conclusions. Finally, the review included only published articles in English language and there may have been unpublished articles and articles in non-English-language that may have been missed.

Given the lack of research on brief parenting interventions, further research is needed and should aim to: compare brief with longer interventions; include independent measures of child outcomes; include control groups at follow-up; include fathers in the parenting interventions and report on father outcomes; include parents of children with more severe externalizing behaviors; and examine which discrete parenting strategies are associated with intervention efficacy.

References

Axelrad, M. E., Butler, A. M., Dempsey, J., & Chapman, S. G. (2013). Treatment effectiveness of a brief behavioral intervention for preschool disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 30, 323–332.

Bower, P., & Gilbody, S. (2005). Stepped care in psychological therapies: Access, effectiveness and efficiency. Narrative literature review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 11–17.

Bradley, S. J., Jadaa, D. A., Brody, J., Landy, S., Tallett, S. E., Watson, W., et al. (2003). Brief psychoeducational parenting program: An evaluation and 1-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 1171–1178.

Brauner, C. B., & Stephens, C. B. (2006). Estimating the prevalence of early childhood serious emotional/behavioral disorders: Challenges and recommendations. Public Health Reports. Special Report on Child Mental Health, 121, 303–310.

Chorpita, F., Daleiden, E. L., Ebesutani, C., Young, J., Becker, K. D., Nakamura, B. J., et al. (2011). Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18, 154–172.

Colman, I., Murray, J., Abbott, R. A., Maughan, B., Kuh, D., Croudace, T. J., & Jones, P. B. (2009). Outcomes of conduct problems in adolescence: 40 year follow-up of national cohort. British Medical Journal, 338, a2981. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2981.

de Graaf, I., Speetjens, P., Smit, F., de Wolff, M., & Tavecchio, L. (2008a). Effectiveness of the Triple P Positive Parenting Program on behavioural problems in children: A meta-analysis. Behavior Modification, 32, 714–735.

de Graaf, I., Speetjens, P., Smit, F., de Wolff, M., & Tavecchio, L. (2008b). Effectiveness of the Triple P Positive Parenting Program on Parenting: A meta-analysis. Family Relations, 57, 553–566.

Dishion, T. J., Connell, A., Weaver, C., Shaw, D., Gardner, F., & Wilson, M. (2008). The family check-up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behaviour support in early childhood. Child Development, 79, 1395–1414.

Dittman, C. K., Farrugia, S. P., Keown, L. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2015). Dealing with disobedience: An evaluation of a brief parenting intervention for young children showing noncompliant behavior problems. Child Psychiatry and Human Development,. doi:10.10007/s10578-015-0548-9.

Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 52, 377–384.

Eyberg, S., Boggs, S. R., & Algina, J. (1995). Parent–child interaction therapy: A psychosocial model for the treatment of young children with conduct problem behavior and their families. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 31, 83–91.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., & Boggs, S. R. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 218–237.

Eyberg, S. M., & Pincus, D. (1999). Eyberg child behavior inventory and Sutter–Eyberg student behavior inventory-revised: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Ridder, E. M. (2005). Show me the child at seven: The consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 46, 837–849.

Fletcher, R., Freeman, E., & Matthey, S. (2011). The impact of behavioral parent training on fathers’ parenting: A meta-analysis of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Fathering, 9, 291–312.

Furukawa, T. A., Noma, H., Caldwell, D. M., Honyashiki, M., Shinohara, K., Imai, H., et al. (2014). Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: A contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 130, 181–192.

Gardner, F., Connell, A., Trenacosta, C. J., Shaw, D., Dishion, T. J., & Wilson, W. N. (2009). Moderators of outcome in a brief family-centered intervention for prevention early problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 543–553.

Glasgow, R. E., Vogt, T. M., & Boles, S. M. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 13, 1322–1327.

Haaga, D. A. F. (2000). Introduction ot the speical section on stepped-care models in psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 547–548.

Heinrichs, N., Bertram, H., Kuschel, A., & Hahlweg, K. (2005). Parent recruitment and retention in a universal prevention program for child behavior and emotional problems: Barriers to research and program participation. Prevention Science, 6, 275–286.

Houtrow, A. J., & Okumura, M. J. (2011). Pediatric mental health problems and associated burden on families. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 6, 222–223.

Joachim, S., Sanders, M. R., & Turner, K. M. T. (2010). Reducing preschoolers’ disruptive behavior in public with a brief parent discussion group. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41, 47–60.

Kazdin, A. E. (1996). Dropping out of child psychotherapy: Issues for research and implications for practice. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 1, 133–156.

Kazdin, A. (2005). Parent management training: Treatment for oppositional, aggressive and antisocial behaviour in children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kazdin, A. (2008). Evidence-based treatments and delivery of psychological services: Shifting our emphases to increase impact. Psychological Services, 5, 201–215.

Kazdin, A. E., & Wassell, G. (1999). Barriers to treatment participation and therapeutic change among children referred for conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 28, 160–172.

Kjøbli, J., & Bjørnebekk, G. (2013). A randomized effectiveness trial of brief parent training: Six-month follow-up. Research on Social Work Practice, 23, 603–612.

Kjøbli, J., & Odgen, T. (2012). A randomized effectiveness trial of brief parent training in primary care settings. Prevention Science, 13, 616–626.

Lavigne, J. V., LeBailly, S. A., Gouze, K. R., Cicchetti, C., Pochyly, J., Arend, R., et al. (2008). Treating oppositional defiant disorder in primary care: A comparison of three models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33, 449–461.

Leijten, P., Dishion, T. J., Thomaes, S., Raaijmakers, M. A. J., de Castro, B. O., & Matthys, W. (2015). Bringing parenting interventions back to the future: How randomized microtrials may benefit parenting intervention efficacy. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 22, 47–57.

Meija, A., Calam, R., & Sanders, M. R. (2015). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a brief parenting intervention in low-resource setting in Panama. Prevention Science,. doi:10.1007/s11121-015-0551-1.

Morawska, A., Adamson, M., Hinchlifee, K., & Adams, T. (2014). Hassle free Mealtimes Triple P: A randomised controlled trial of a brief parenting group for childhood mealtime difficulties. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 53, 1–9.

Morawska, A., Haslam, D., Milne, D., & Sanders, M. R. (2011). Evaluation of a brief parenting discussion group for parents of young children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 32, 136–145.

Nieuwsma, J. A., Trivedi, R. B., McDuffie, J., Kronish, I., Benjamin, D., Williams, J. W. (2011). Brief psychotherapy for depression in primary care: A systematic review of the evidence. VA-ESP Project #09-010.

Nowak, C., & Heinrichs, N. (2008). A comprehensive meta-analysis of Triple P-Positive Parenting Program using hierarchical linear modeling: Effectiveness and moderating variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11, 114–144.

O’Brien, M., & Daley, D. (2011). Self-help parenting interventions for childhood behaviour disorders: A review of the evidence. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37, 623–637.

Ogden, T., & Hagen, K. A. (2008). Treatment effectiveness of Parent Management Training in Norway: A randomized controlled trial of children with conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 6-7-621.

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Eddy, J. M. (2002). A brief history of the Oregon Model. In G. R. P. J. B. Reid & J. Snyder (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention (pp. 3–21). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Perkins, R. (2006). The effectiveness of one session of therapy using a single-session therapy approach for children and adolescents with mental health problems. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 79, 215–227.

Sanders, M. R. (1999). The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2, 71–90.

Sanders, M. R. (2008). Triple P-Positive Parenting Program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 506–517.

Sanders, M. R., & Kirby, J. N. (2010). Parental programs for preventing behavioural and emotional problems in children. In J. Bennet-Levy, D. Richards, P. Farrand, H. Christensen, K. Griffiths, D. Kavanagh, B. Klein, M. Lau, J. Proudfoot, L. Ritterband, J. White, & C. Williams (Eds.), Oxford guide to low intensity CBT interventions (pp. 399–406). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Schappin, R., Wijnroks, L., Venema, M. U., Wijnberg-Williams, B., Veenstra, R., Koopman-Esseboom, C., et al. (2013). Brief parenting intervention for parents of NICU gradulates: A randomized clinical trial of Primary Care Triple P. BMC Pediatrics, 13, 69.

Smith, T. K., Duggan, A., Bair-Merritt, M. H., & Cox, G. (2012). Systematic review of fathers’ involvement in programmes for the primary prevention of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Review, 21, 237–254.

Tarver, J., Daley, D., Lockwood, J., & Sayal, K. (2014). Are self-directed parenting interventions sufficient for externalising behaviour problems in childhood? A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 23, 1123–1137.

Thomas, R., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). Behavioral outcomes of parent–child interaction therapy and triple p-positive parenting program: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 475–495.

Tiano, J. D., & McNeil, C. B. (2005). The inclusion of fathers in behavioral parent training: A critical evaluation. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 27, 1–28.

Turner, K. M. T., & Sanders, M. R. (2006). Help when it’s needed first: A controlled evaluation of brief, preventive behavioral family intervention in a primary care setting. Behavior Therapy, 37, 131–142.

Webster-Stratton, C., & Reid, M. J. (2003). The incredible years parents, teachers and child training series: A multifaceted treatment approach for young children with conduct problems. In A. E. Kazdin & J. R. Weisz (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (pp. 224–240). New York: Guilford.

Wilson, P., Rush, R., Hussey, S., Puckering, C., Sim, F., Allely, C. S., et al. (2012). How evidence-based is an ‘evidence-based parenting program’? A PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis of Triple P. BMC Medicine, 10, 130.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the NSW Institute of Psychiatry who provided a Training Fellowship in Research to the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tully, L.A., Hunt, C. Brief Parenting Interventions for Children at Risk of Externalizing Behavior Problems: A Systematic Review. J Child Fam Stud 25, 705–719 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0284-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0284-6