Abstract

The family system has frequently been suggested to play an important role in adolescents’ health. Particularly, conflict within the marital dyad has been associated with maladjustment among adolescents, although studies have rarely focused on disordered eating as a possible negative outcome. In this study, we examined the direct association between marital conflict and disordered eating among 123 adolescent girls in middle school and high school. We also tested the mediating role of adolescents’ positive relationship quality with their mothers and fathers (e.g., high warmth and low control) in this relation. For our hypothesized direct effects and mediation models, we formed latent constructs with cross-sectional data collected from girls’ self-report questionnaires and applied bootstrapping procedures. We found that marital conflict was both directly and indirectly, via poor mother– and father–adolescent relationship quality, associated with girls’ disordered eating. This suggests that the mother–father, mother–adolescent, and father–adolescent family subsystems can play a part in influencing girls’ eating patterns. Clearly, family subsystems have significant roles in promoting the health of young, female adolescents. Future research and treatment efforts for girls exhibiting disordered eating should aim to include family members and address the roles of different family subsystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Marital conflict has long been linked with problematic, unhealthy development among children and adolescents. For example, research has shown that marital conflict is strongly associated with internalizing and externalizing behaviors, including conduct problems, depression, anxiety, poor academic success, and impaired social relationships among children ranging in age from elementary school to high school (for a review, see Rhoades 2008). Despite this wealth of research, studies have failed to thoroughly examine the effect of marital conflict on adolescents’ disordered eating, or unhealthy eating- and weight-related behaviors such as drive for thinness, dieting, food restriction, bingeing, and purging, that do not meet clinical diagnostic criteria for a full-blown eating disorder. Longitudinal research has demonstrated the importance of focusing on the correlates and precursors of adolescents’ disordered eating with findings indicating that individuals, particularly girls, who engage in disordered eating during adolescence are likely to continue or increase these harmful behaviors 10 years later (Neumark-Sztainer et al. 2011). Engaging in disordered eating during adolescence may also lead to obesity or eating disorders (Neumark-Sztainer et al. 2006). Thus, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the direct association between marital conflict and adolescent girls’ disordered eating, as well as the mediating roles of both mother–adolescent and father–adolescent relationship quality. Specifically, we examined relationship quality as a combination of warmth (care and empathy in the parent–adolescent relationship) and control (excessive parental involvement in the adolescent’s affairs).

Family systems theory suggests that families must be understood as an interdependent unit, such that all family members influence the way each member functions and that the family cannot be understood by isolating one part (Cox and Paley 1997; Magnavita 2012; Minuchin 1974). Problem behaviors exhibited in one family member (e.g., the adolescent) exist in the context of an imbalance in functioning within the family system (Minuchin 1974). Thus, each family member plays an important role. Initial work guided by the family systems approach typically focused on the parent–child relationship, but there has been a shift towards a consideration of the interactions between multiple family subsystems, including the marital relationship as well as the mother–child and father–child relationships (Cox and Paley 2003). Clearly, adolescent behavior cannot be understood without focusing on familial subsystem relationships, yet more research investigating the interactions of multiple familial risk factors is necessary (Littleton and Ollendick 2003). Therefore, we sought to examine how marital conflict and parent–adolescent relationship quality, with both mothers and fathers, were directly and indirectly associated with girls’ disordered eating.

It would not be surprising to find that marital conflict has negative impacts on both the parent–adolescent relationship and adolescents’ disordered eating. Marital conflict threatens a child’s emotional security and feelings of safety within the family unit, thereby damaging the parent–child relationship and likely leading to a disruption in the child’s regulation and coping mechanisms (Davies and Cummings 1994; Grych et al. 2000; Harold et al. 2004). When children perceive that their safety is being threatened, they experience a decrease in effective coping mechanisms as well as increased anxiety, fear, helplessness, and self-blame (Grych and Fincham 1990; Grych et al. 2003; Rhoades 2008). Such inefficient coping and internalized distress may be then exhibited AS physical symptoms, including health risk behaviors such as disordered eating (Troxel and Matthews 2004).

A small body of research suggests that marital functioning may play a role in the development of disordered eating, but the processes involved in the transmission of effects remain unclear. First, studies indicate that adolescents whose parents are divorced or separated have increased risk of developing disordered eating (Martínez-González et al. 2003; Suisman et al. 2011). Second, additional studies provide insight into the effects of marital conflict on individuals’ eating patterns, but most of this work has involved samples of adult women with clinically diagnosed eating disorders. For example, in a sample of women with bulimia nervosa, 44 % reported long-standing conflict within their parents’ relationship, marked by arguments, violence, infidelity, and separation (Lacey et al. 1986). Similarly, women with eating disorders have noted greater parental marital disharmony than women without eating disorders, despite similar divorce rates (Dolan et al. 1990; Wade et al. 2007). In another study involving reports from both mothers and fathers on marital conflict, higher levels of subclinical bulimic symptoms among adult children were significantly associated with both parents’ reports of marital conflict (Wade et al. 2001). Although the afore-mentioned study investigated subclinical as well as clinical levels of bulimia nervosa, it did not include an adolescent sample or patient perspectives. In the present study, we targeted adolescents because they are an age group that is relatively understudied yet show increasing tendencies towards the development of disordered eating (Littleton and Ollendick 2003). In addition, we chose to focus specifically on adolescents’ reports of family functioning because adolescents’ perceptions of parenting may have more influence on their adjustment than their parents’ actual or self-reported behaviors (Laird et al. 2003).

Despite this research, it remains uncertain whether marital conflict has a direct impact or is part of a mediating process involving parent–adolescent relationship quality. In many models examining the effects of marital conflict on adolescent adjustment, parenting is hypothesized to serve as a mediating mechanism (e.g., the parenting process model; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2007). For instance, negative parenting behaviors such as lack of warmth and psychological control have been tested as mediators of the connections between marital conflict and children’s externalizing and internalizing behaviors (e.g., Benson et al. 2008; Cui and Conger 2008; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2007). Therefore, it seems likely that marital conflict, parenting, and adolescents’ disordered eating are entwined. Parent–child difficulties may emerge from within a familial context of marital conflict and ultimately lead to disordered eating (Lacey et al. 1986). In order to examine the indirect, and possibly mediating, connections among marital conflict, parent–adolescent relationship quality, and adolescents’ disordered eating, we must establish separate connections between the constructs.

First, the marital relationship is likely to affect other subsystems within the family, including spillover to the parent–child subsystem (Cox and Paley 1997; Zimet and Jacob 2001). For example, marital conflict predicted low levels of parental warmth and support for adolescents 1 year later (Cui and Conger 2008). Specifically among adolescent girls, marital conflict was related to lower levels of parental warmth and attachment as well as higher levels of psychological control (Doyle and Markiewicz 2005). Parents who are distressed may lack the ability, focus, and resources necessary to tolerate daily childrearing challenges and may, in turn, have poor relationships with their children (Fauber et al. 1990; Gerard et al. 2006; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2007). Additionally, couples who withdraw from their marital relationships when conflict arises may become emotionally unavailable to their children (Sturge-Apple et al. 2006). We could also speculate that parents who experience conflict are concerned about the end of their marital relationship or the safety of their children, which is perhaps why they might engage in controlling behaviors. Thus, marital conflict can have a significant impact on the overall health of the family system through potential effects on parenting.

Second, individual’s perceptions of parenting are closely tied with their disordered eating. Among females with an eating disorder, 60 % reported poor relationships with parents (Lacey et al. 1986). Women with eating disorders recalled that their fathers in particular were controlling and that both parents lacked warmth (Calam et al. 1990; Dolan et al. 1990; Wade et al. 2007). Among adolescent girls, parental control (e.g., overprotection) and lack of warmth (e.g., care) were associated with subclinical levels of disordered eating (McEwen and Flouri 2009; Neumark-Sztainer et al. 2000; Turner et al. 2005). Poor parent–child relationships can lead to internalized distress such as shame, anxiety, and low self-competence (Blodgett Salafia et al. 2009; Turner et al. 2005) or affect the child’s ability to properly regulate behaviors and emotions (McEwen and Flouri 2009), which may in turn make children more vulnerable to physical health problems (Troxel and Matthews 2004). More specifically, parental control may prevent an adolescent from developing autonomy or establishing her own identity, which are important developmental tasks of adolescence. It is also possible that inadequate parental warmth leads to feelings of ineffectiveness in the adolescent who then uses disordered eating behaviors to cope with such feelings (Striegel-Moore and Cachelin 1999). It is evident that the parent–adolescent relationship plays an important role in the process leading to adolescents’ engagement in unhealthy eating behaviors.

Only one study to date has focused on connections among the marital relationship, parent–child relationship, and eating disorders. In that particular study, using a small sample of thirty Jewish women from Israel, the researchers found that parent–child relationship quality served as a mediator between parents’ marital quality and the severity of their adult child’s clinically diagnosed eating disorder symptoms (Latzer et al. 2009). Our study expands on this prior work in that we specifically focus on marital conflict as one component of the marital relationship as well as two important dimensions of the parent–child relationship, warmth and control. Our study also differs in that we look at relationship quality with both mothers and fathers, and do so in a sample of adolescent girls.

Although there is theoretical and empirical support for our proposed connections between marital conflict, parent–adolescent relationship quality, and adolescents’ disordered eating, further research is necessary to be able to thoroughly examine the direct and indirect connections between these constructs, especially in a young female sample. Therefore, in the present study, we sought to determine whether marital conflict was directly associated with adolescent girls’ disordered eating and whether this relationship was mediated by girls’ relationships with both their mothers and fathers. We chose to examine both mediators simultaneously in one model as it has been suggested that including multiple mediators in one model is more appropriate than testing separate models (Preacher and Hayes 2008). We hypothesized that higher levels of marital conflict would be associated with higher levels of girls’ disordered eating, and that poor mother– and father–adolescent relationship quality (e.g., low warmth and high control) would mediate, or explain, this connection.

Method

Participants

The data analyzed in the present study were collected as part of a larger project reviewed and approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. The aim of the larger study was to investigate factors associated with adolescents’ disordered eating behaviors and body image. There were 134 girls in the original study, but some girls’ data was excluded from analysis in the present study, as discussed below. In the present study, participants were 123 adolescent girls in middle school (N = 79) or high school (N = 44). This represents approximately 20 % of the total number of girls attending the middle school and nearly 10 % of the total number of girls attending the high school at the time of the study. All interested students at the middle school received information regarding the study from a guidance counselor, whereas only students taught by one particular teacher were recruited from the high school.

Girls ranged in age from 12 to 19 years (M = 14.81, SD = 1.65) and were in grades 7–12. Consistent with the ethnic composition of the city and of the school district, most of the sample identified themselves as White (94 %). Additionally, 4 % identified themselves as Native American, and approximately 2 % identified as Black, Latina, or other (i.e., one person identified as each). As a proxy measure of socioeconomic status, girls were asked to report their parents’ highest level of education. The majority of girls reported that their mothers and fathers completed college (63 and 50 % respectively). Fewer girls reported that their mothers completed some high school (2 %), high school (11 %), some college (13 %), and an advanced degree (8 %) and that their fathers completed grade school (2 %), some high school (5 %), high school (20 %), some college (14 %), and an advanced degree (7 %). Two girls did not report their mothers’ or fathers’ education, and one girl did not report only her father’s education. Using girls’ self-reported height and weight, the average Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated to be 21.25 (SD = 4.26), which was in the normal range (≤18.49 is underweight, 18.5–24.99 is normal weight, 25–29.99 is overweight, and ≥30 is obese, according to national standards set by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention). BMI for four girls was not calculated, as they did not report their height or weight.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from flyers and parental consent forms distributed to students at a Midwestern middle school and high school over a period of 1 year. Individuals under the age of 18 who returned parental consent forms were then invited to complete assent forms and a packet of surveys before or after school. Individuals aged 18 or older did not complete parental consent forms but filled out their own consent forms and surveys. Participants took between 1 and 2 h to complete their survey packets. In compensation for their participation, adolescents received a $25 giftcard to a local mall.

Measures

For the present study, we used girls’ self-reports of perceived marital conflict, mother–adolescent relationship quality, father–adolescent relationship quality, and disordered eating patterns. We chose widely-used, well-established measures that have demonstrated evidence of reliability and validity in previous work. As with most survey research, missing data existed. If a participant did not complete measures about either her mother or her father (or both), her data was excluded from analysis because we did not know if the adolescent had any contact with her parent(s) or if the parent(s) was(were) deceased. Otherwise, missing data were estimated. Descriptive statistics for the study variables are reported in Table 1.

Marital Conflict

To assess marital conflict as perceived by the adolescent, we used 3 subscales of the 48-item Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIC; Grych et al. 1992). The subscales measured the Frequency (6 items), Intensity (7 items), and Resolution (6 items) of marital conflict according to the adolescents. These subscales had previously been found to load onto the same “Conflict Properties” dimension in factor analyses (Bickham and Fiese 1997; Grych et al. 1992). Sample items were, “I often see my parents arguing” (Frequency), “My parents get really mad when they argue” (Intensity), and “Even after my parents stop arguing they stay mad at each other” (Resolution). Items were scored on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (False) to 2 (True). Higher scores indicated more perceived marital conflict.

Construct validity was previously demonstrated among a sample of children with the CPIC being significantly correlated with the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (r = .46) (McDonald and Grych 2006). Additionally, the “conflict properties” factor (including the CPIC subscales of Frequency, Intensity, and Resolution) was significantly related to early adolescent girls’ reports of externalizing and internalizing behaviors (r = .26–.31) (Grych et al. 1992). Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for the “Conflict Properties” factor was estimated at .95 among a sample of late adolescent girls (Bickham and Fiese 1997). Previous work has also provided evidence of high reliability for each of the individual scales among a sample of 4th and 5th grade girls and boys (α = .70 to .83) (Grych et al. 1992). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the individual subscales were .83 (Frequency), .86 (Intensity), and .88 (Resolution).

Parent–Adolescent Relationship Quality

We asked girls to complete separate but identical assessments for mothers and fathers regarding relationship quality using the 25-item Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; Parker et al. 1979). The PBI measures children’s perceptions of the level and type of bonding between parent and child. The scale is divided into two subscales: the Care subscale (12 items) which measures parents’ warmth and involvement versus indifference and rejection, and the Overprotection subscale (13 items) which measures parents’ control and intrusion versus encouragement of independence (Parker et al. 1979). Sample items included, “My father seemed emotionally cold to me” (Warmth) and “My mother tried to control everything I did” (Control). Adolescents were asked to respond how much each of these statements was like or unlike their given parent on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (Very Unlike) to 3 (Very Like). Items were scored such that higher scores indicated a more positive relationship (e.g., higher levels of warmth and lower levels of control). According to Parker and colleagues (Parker et al. 1979), this represents optimal bonding. Similarly, in their study examining parenting and eating disorder symptomatology, Lobera et al. (2011) combined scores on the Care and Overprotection subscales to represent an overall parenting style, such that high warmth and low control indicated an optimal style. In our analyses, we similarly defined positive parent–adolescent relationship quality as high warmth and low control, which allowed both PBI subscales to load similarly under one factor in our latent variable analysis (described below).

Construct validity of the PBI has been determined using the Adult Attachment Index (AAI) among a sample of adolescent girls and boys who reported on their mothers, as there were significant correlations in the expected directions between the Care subscale of the PBI and the loving/unloving, rejecting, and neglect subscales of the AAI (r = .39, −41, and −.46, respectively) as well as between the Overprotection subscale of the PBI and the neglect subscale of the AAI (r = .28) (Manassis et al. 1999). In a previous study of high school-aged adolescents, internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was determined as .75 for mothers and .80 for fathers for the Care subscale of the PBI, and .82 for mothers and .83 for fathers for the Overprotection subscale (Canetti et al. 1997). Additionally, Parker et al. (1979) reported a split-half reliability estimate of .88 for the Care subscale and .74 for the Overprotection subscale. In the present study, for the Care subscale, Cronbach’s alpha was .89 for mothers and .89 for fathers. For the Overprotection subscale, Cronbach’s alpha was .85 for mothers and .83 for fathers.

Adolescent Disordered Eating

To assess disordered eating patterns, girls reported on three different measures: the 7-item Drive for Thinness subscale of the Eating Disorders Inventory (DFT; Garner et al. 1983), the 10-item Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire Restraint Scale (DEBQ-R; van Strien et al. 1986), and the 26-item Children’s Version of the Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT; Maloney et al. 1988). These questionnaires were chosen to represent a wide range of disordered eating behaviors including drive for thinness (DFT), dieting (DEBQ-R), and preoccupation with food and weight (ChEAT).

Sample items for the DFT included, “If I gain a pound, I worry that I will keep gaining” and “I am preoccupied with the desire to be thinner.” Adolescents responded to each item on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 5 (Always). Sample items for the DEBQ-R included, “Do you try to eat less at meal times than you would like to eat?” and “Do you deliberately eat foods that are slimming?” Adolescents responded to each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Very Often). Sample items for the ChEAT included, “Do you vomit after eating?” and “Do you think about wanting to be thinner?” Each item was scored on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 5 (Always). For all three measures, higher scores indicated more disordered eating.

Construct validity of the DFT has been demonstrated by its significant positive relations with dieting (r = .77) and body dissatisfaction (r = .83) among girls in 8th grade (Blodgett Salafia et al. 2007). In addition, the DFT had acceptable internal consistency (α = .81) in a sample of girls between the ages of 11 and 18 (Shore and Porter 1990). Construct validity for the DEBQ-R has been demonstrated by its significant correlations in the expected directions with women’s emotional eating (r = .33; van Strien et al. 1986) as well as with adolescent girls’ external eating, or eating behaviors in response to external food cues regardless of internal states of hunger and fullness (r = −.13; Snoek et al. 2007). Cronbach’s alpha of the DEBQ-R was .92 among a sample of 11–16-year old adolescent girls and boys (Snoek et al. 2007). For the ChEAT, construct validity was demonstrated in prior work, as the scale was significantly correlated with weight management behavior (r = .36) and with body dissatisfaction (r = .39) among girls in middle school (Smolak and Levine 1994). In the same study, internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of the ChEAT was estimated at .87 (Smolak and Levine 1994). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .88 for the DFT, .95 for the DEBQ-R, and .88 for the ChEAT.

Results

Proposed Analytical Method

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) in MPlus 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén 2012) to test our proposed models. SEM was used primarily for two important reasons: first, SEM provides unbiased estimates when investigating latent variables with multiple indicators and second, SEM allows for the analysis of a more complicated multiple mediator model (Cheung and Lau 2008). More specifically, we used bootstrapping procedures. Bootstrapping is the preferred method for examining multiple mediator models with small sample sizes of around 100 because it provides sufficient power to detect a medium to large mediation effect (Cheung and Lau 2008; Preacher and Hayes 2008). With multiple mediator models, bootstrapping is advantageous because it allowed us to investigate the total indirect effect as well as the specific indirect effects associated with each mediator (Preacher and Hayes 2008). Essentially, bootstrapping is a resampling procedure that does not impose the assumption of normality on data, thereby reducing bias (Preacher and Hayes 2008; Shrout and Bolger 2002). It involves treating the study’s sample as a larger population, from which the researchers can draw a number of random samples with continuous replacement. In our analyses, we followed the general recommendation to use bootstrapping procedures with 10,000 iterations (Mallinckrodt et al. 2006). We used maximum likelihood estimation to appropriately handle missing data.

Latent Constructs

Correlations are reported in Table 2. Because it is possible that BMI and age may have significant effects on the proposed relationships between our constructs, we included both variables in our correlational analyses. As evident in Table 2, girls’ age did not significantly correlate with any of the study variables; therefore, it was excluded from any additional analyses. However, girls’ BMI was significantly related to several of the study constructs, primarily disordered eating behaviors. We decided to examine our path models while controlling for BMI.

Significant correlations between the proposed indicators provided support for the formation of latent constructs from multiple indicators for marital conflict (r = .77–.84), positive mother–adolescent relationship quality (r = .64), positive father–adolescent relationship quality (r = .46), and girls’ disordered eating (r = .72–.83). We then constructed and tested a structural measurement model before examining our hypothesized direct effects and mediation models. The measurement model consisted only of paths between latent variables and their corresponding manifest indicators, with no specified structural relations except correlations between the latent variables. This model produced significant factor loadings for all manifest variables on their respective latent constructs. In addition, the model showed significant correlations in the expected directions between constructs. Fit statistics indicated an acceptable model fit: χ2(29, N = 123) = 61.02, p < .05; CFI = .96; RMSEA = .095 with 90 % CIs [.06, .13], SRMR = .047.

Direct Connection Between Marital Conflict and Girls’ Disordered Eating

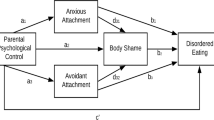

We then examined the direct connection between marital conflict and girls’ disordered eating patterns (see Fig. 1; results are reported as standardized coefficients). Results indicated that marital conflict and girls’ disordered eating patterns were related such that higher levels of marital conflict were associated with higher levels of girls’ disordered eating (β = .27; p < .05). Fit statistics indicated an acceptable model fit: χ2(8, N = 123) = 13.56, p = .09; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .075 with 90 % CIs [.00, .14], SRMR = .022.

When we re-ran this model controlling for girls’ BMI, we saw that marital conflict still had a significant association with girls’ disorder eating (β = .21; p < .05) and also that BMI had a significant association with disordered eating (β = .34; p < .05). Because the direct connection remained significant even after accounting for BMI, we proceeded to test our mediation model.

Parent–Adolescent Relationship Quality as Mediators

Our next model included the two possible mediators, mother–adolescent and father–adolescent relationship quality (see Fig. 2). Results indicated that marital conflict was negatively related to both mother–adolescent (β = −.57; p < .05) and father–adolescent (β = −.55; p < .05) relationship quality. Additionally, both mother–adolescent and father–adolescent relationship quality were negatively related to girls’ disordered eating (β = −.15; p < .10 and β = −.30; p < .05, respectively). Furthermore, the sum of these indirect effects was significant (β = .25; p < .05). When mother–adolescent relationship quality was considered separately as a mediator, the indirect effect was not statistically significant at .08 (p > .05); for father–adolescent relationship quality, the indirect effect was marginally significant at .16 (p < .10). Our results indicate that higher marital conflict was associated with less positive, or poorer, parent–adolescent relationships which were, in turn, associated with more disordered eating among girls. In this model, the direct effect of marital conflict on girls’ disordered eating was no longer significant (β = .04; p > .05). This suggests that mediation had occurred such that mother–adolescent and father–adolescent relationship quality explained the link between marital conflict and girls’ disordered eating. Fit statistics indicated an acceptable model fit for our mediation model: χ2(30, N = 123) = 79.10, p < .05; CFI = .94; RMSEA = .012 with 90 % CIs [.09, .15], SRMR = .075.

When controlling for BMI in our mediation model, our results remained the same such that all connections between constructs were significant. Thus, to simplify the model we present in Fig. 2, the findings do not include BMI.

Discussion

Because the family system has frequently been suggested to play an important role in adolescents’ health, we examined the direct and indirect relationships between marital conflict and the disordered eating patterns of adolescent girls. Specifically, we found that higher perceived levels of marital conflict were directly associated with higher levels of girls’ disordered eating. In addition, we found that this relation was mediated by both mother–adolescent and father–adolescent relationship quality, specifically low levels of warmth and high levels of control. Ultimately, this suggests that the mother–father, mother–adolescent, and father–adolescent family subsystems can play influential roles in girls’ eating patterns.

Our study parallels other empirical findings implicating marital conflict as a risk factor in the development of a variety of unhealthy behaviors among adolescents, although none of which has examined subclinical levels of disordered eating in adolescent girls. Marital conflict threatens an adolescent’s emotional security and is often associated with internalizing and externalizing problems among girls (Davies and Cummings 1994; Harold et al. 2004; Rhoades 2008). Girls may experience emotional dysregulation and difficulty coping as a result of marital conflict which, in turn, can lead to affective, behavioral, and cognitive difficulties (Troxel and Matthews 2004). Disordered eating, as defined in our study, is a combination of affective (i.e., drive for thinness), behavioral (i.e., dieting), and cognitive (i.e., preoccupation with food and weight) components, which helps explain our finding that marital conflict and girls’ disordered eating are linked. Our study is the first study we know of to specifically examine associations between marital conflict and girls’ disordered eating during adolescence.

We also saw evidence that both mother–adolescent and father–adolescent relationship quality served as indirect links in the relationship between marital conflict and girls’ disordered eating patterns. First, higher levels of marital conflict were associated with poorer, less positive relationships with mothers and fathers, which included low warmth and high control. This finding coincides with other empirical work that has linked marital conflict with decreased parental warmth and increased control (Cui and Conger 2008; Doyle and Markiewicz 2005). Individuals in couples that experience high levels of conflict may withdraw from their familial relationships and be less emotionally available for their children (Fauber et al. 1990; Sturge-Apple et al. 2006). Children may, in turn, view this emotional unavailability as a lack of parental warmth. At the same time, however, it is possible that parents may attempt to secure strong emotional attachments and high levels of support from their children (Fauber et al. 1990), which children then interpret as excessive control.

Second, results from our study indicated that poorer, less positive relationships with mothers and fathers were related to higher levels of girls’ disordered eating. Other studies have supported the notion that a poor parenting style may result in ineffective regulation or coping of adolescents, who then express themselves behaviorally through disordered eating (Blodgett Salafia et al. 2007; McEwen and Flouri 2009), and our findings are consistent with such work. Parental behaviors such as low warmth and high control likely interfere with an adolescent girl’s ability to develop autonomy and self-competence, establish her own identity, and learn effective ways of dealing with internalized distress (Blodgett Salafia et al. 2009; Striegel-Moore and Cachelin 1999; Turner et al. 2005).

Although parent–adolescent relationship quality has frequently been described as a mediator of the relation between marital distress and adolescent maladjustment (e.g., Benson et al. 2008; Cui and Conger 2008; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2007), ours is only the second known study to examine disordered eating as the outcome variable and the only known study to do so while focusing exclusively on the time period of adolescence. More specifically, we extend previous work by Latzer et al. (2009) by using a sample of young adolescent girls without clinically diagnosed eating disorders, focusing on marital conflict, and including perceptions of two parenting dimensions within both the mother–adolescent and the father–adolescent relationship. Our findings provide support for family systems theory and the importance of various familial subsystems’ effects on adolescent well-being. Clearly, adolescents are part of a larger, interdependent familial unit and are affected by imbalances that occur within that unit.

Care should be taken when interpreting these findings as to not generalize beyond the limited sample and measurements used in this study. For instance, our sample was a small, relatively homogeneous group of girls in terms of age, ethnicity, BMI, socioeconomic status, parental status, and household composition; thus our results may not generalize to other groups. It will be important for other researchers to identify the possible role of each of these constructs and examine differences among groups, especially using larger samples in order to detect all possible effects. We also had two measurement limitations. First, we did not assess the frequency of contact that participants had with mothers and fathers or the frequency of contact that they witnessed between their parents. Second, we did not measure clinical symptoms of eating disorders, nor did we have access to prior levels of symptomatology. Finally, we are unable to conclude that difficulties within family subsystems cause unhealthy behaviors due to our lack of longitudinal or experimental data. In addition, it may be possible that a different process exists, such that difficulties within the parent–adolescent dyad may first lead to marital conflict, which then is associated with disordered eating. Future studies should seek to expand on the findings of this study using more diverse samples, clinical assessments, and longitudinal data.

Despite limitations, the present study contributes to the field in a number of ways. First, our sample was comprised of middle school and high school adolescent girls. Adolescents are especially vulnerable to the development of body dissatisfaction, dieting, and eating disorders, although the majority of studies on risk factors tend to focus on late adolescents or emerging adults (for reviews, see Levine and Smolak 2009 and Thompson et al. 1999; see also Littleton and Ollendick 2003). In particular, during early adolescence, girls’ body dissatisfaction and rates of eating disorders increase considerably (Bearman et al. 2006; Swanson et al. 2011). Furthermore, individuals are at high risk of continuing or increasing unhealthy eating behaviors into adulthood if they have already engaged in disordered eating during adolescence (Neumark-Sztainer et al. 2006, 2011). Thus, it is essential to examine the factors associated with and the processes involved in determining eating problems during adolescence.

Second, we had several methodological and analytical strengths, including the use of well-established, widely-used measures that have demonstrated evidence of reliability and validity in both past research as well as the present study. This allowed us to form latent constructs for all of our variables. We also investigated both mediators simultaneously in the same model. Lastly, it is worth noting that we were able to collect adolescents’ reports on relationship quality with both mothers and fathers. Historically, eating disorders researchers have given primary focus to the mother–daughter subsystem, which creates maternal blame and neglects other relational dynamics within families, such as in father–daughter dyads.

Our findings ultimately contribute to the growing field of research examining the connections between marital conflict and adolescents’ health. Previous research had already identified several negative outcomes for adolescents as a result of marital conflict, and our findings extend this research by establishing a significant association between marital conflict and adolescent girls’ disordered eating. In addition, although cross-sectional in nature, our findings illustrate the important role of warmth and control within the parent–adolescent relationship in the process connecting marital conflict to girls’ disordered eating, suggesting that it may be more than a simple direct link. Problems within the marital dyad may be associated with difficulties in the parent–adolescent subsystem, which can ultimately contribute to girls’ well-being. It is possible that a female adolescent may express her distress with how the marital and parent–adolescent subsystems are functioning by engaging in unhealthy eating behaviors.

Positive inter-familial relationships may be associated with fewer maladaptive eating behaviors among adolescents including preoccupation with food and weight, unhealthy dieting, drive for thinness, food restriction, bingeing, and purging. We encourage researchers, educators, and therapists to use this information in their work. For example, therapy, prevention, and interventions programs focusing on eating disorders should not only target adolescents but also include their parents. In particular, therapists will want to address and work to decrease marital conflict within the setting of couples’ therapy as well as assist parents and adolescents in building positive, caring relationships within the setting of family therapy. Prevention and intervention programs should not only simply include parents but also educate them about the negative effects of marital conflict and poor parent–adolescent relationship quality as well as teach age-specific parenting strategies that include warmth and appropriate control. Future research and treatment efforts for eating disorders ultimately need to include family members and address the risk and protective roles that family plays in adolescents’ disordered eating.

References

Bearman, S. K., Presnell, K., Martinez, E., & Stice, E. (2006). The skinny on body dissatisfaction: A longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 229–241. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9.

Benson, M. J., Buehler, C., & Gerard, J. M. (2008). Interparental hostility and early adolescent problem behavior: Spillover via maternal acceptance, harshness, inconsistency, and intrusiveness. Journal of Early Adolescence, 28, 428–454. doi:10.1177/0272431608316602.

Bickham, N., & Fiese, B. (1997). Extension of the children’s perceptions of interparental conflict scale for use with late adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 246–250. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.11.2.246.

Blodgett Salafia, E. H., Gondoli, D. M., Corning, A. F., Bucchianeri, M. M., & Godinez, N. M. (2009). Longitudinal examination of maternal psychological control and adolescents’ self-competence as predictors of bulimic symptoms among boys and girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42, 422–428. doi:10.1002/eat.20626.

Blodgett Salafia, E. H., Gondoli, D. M., Corning, A. F., McEnery, A. M., & Grundy, A. M. (2007). Psychological distress as a mediator of the relation between perceived maternal parenting and normative maladaptive eating among adolescent girls. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 434–446. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.54.4.434.

Calam, R., Waller, G., Slade, P., & Newton, P. (1990). Eating disorders and perceived relationships with parents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 479–485. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199009)9:5<479:AID-EAT2260090502>3.0.CO;2-I.

Canetti, L., Bachar, E., Galili-Weisstub, E., Kaplan De-Nour, A., & Shalev, A. (1997). Parental bonding and mental health in adolescence. Adolescence, 32, 381–394.

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2008). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 11, 296–325. doi:10.1177/1094428107300343.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 193–196. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01259.

Cui, M., & Conger, R. D. (2008). Parenting behavior as mediator and moderator of the association between marital problems and adolescent maladjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18, 261–284. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00560.

Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. M. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 387–411. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387.

Dolan, B. M., Lieberman, S., Evans, C., & Lacey, J. H. (1990). Family features associated with normal body weight bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 639–647. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199011)9:6<639:AID-EAT2260090606>3.0.CO;2-H.

Doyle, A. B., & Markiewicz, D. (2005). Parenting, marital conflict, and adjustment from early- to mid-adolescence: Mediated by adolescent attachment style? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 97–110. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-3209-7.

Fauber, R., Forehand, R., Thomas, A. M., & Wierson, M. (1990). A mediational model of the impact of marital conflict on adolescent adjustment in intact and divorced families: The role of disrupted parenting. Child Development, 61, 1112–1123. doi:10.2307/1130879.

Garner, D. M., Olmstead, M. P., & Polivy, J. (1983). Development and validation of multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 2, 15–34. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198321)2:2<15:AID-EAT2260020203>3.0.CO;2-6.

Gerard, J. M., Krishnakumar, A., & Buehler, C. (2006). Marital conflict, parent-child relations, and youth maladjustment: A longitudinal investigation of spillover effects. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 951–975. doi:10.1177/0192513X05286020.

Grych, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (1990). Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 267–290. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267.

Grych, J. H., Fincham, F. D., Jouriles, E. N., & McDonald, R. (2000). Interparental conflict and child adjustment: Testing the mediational role of appraisals in the cognitive contextual framework. Child Development, 71, 1648–1661. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00255.

Grych, J. H., Harold, G. T., & Miles, C. J. (2003). A prospective investigation of appraisals as mediators of the link between interparental conflict and child adjustment. Child Development, 74, 1176–1193. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00600.

Grych, J. H., Seid, M., & Fincham, F. D. (1992). Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: The children’s perception of interparental conflict scale. Child Development, 63, 558–572. doi:10.2307/1131346.

Harold, G. T., Shelton, K. H., Goeke-Morey, M. C., & Cummings, E. M. (2004). Marital conflict, child emotional security about family relationships and child adjustment. Social Development, 13, 350–376. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00272.x.

Lacey, J. H., Coker, S., & Birtchnell, S. A. (1986). Bulimia: Factors associated with its etiology and maintenance. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5, 475–487. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198603)5:3<475:AID-EAT2260050306>3.0.CO;2-0.

Laird, R. D., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (2003). Parents’ monitoring knowledge and adolescents’ delinquent behavior: Evidence of correlated developmental changes and reciprocal influences. Child Development, 74, 752–768. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00566.

Latzer, Y., Lavee, Y., & Gal, S. (2009). Marital and parent-child relationships in families with daughters who have eating disorders. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 1201–1220. doi:10.1177/0192513X09334599.

Levine, M. P., & Smolak, L. (2009). Recent developments and promising directions in the prevention of negative body image and disordered eating in children and adolescents. In L. Smolak & J. K. Thompson (Eds.), Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: Assessment, prevention, and treatment (2nd ed., pp. 215–239). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Littleton, H. L., & Ollendick, T. (2003). Negative body Image and disordered eating behavior in children and adolescents: What places youth at risk and how can these problems be prevented? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6, 51–66. doi:10.1023/A:1022266017046.

Lobera, I. J., Rios, P. B., & Casals, O. G. (2011). Parenting styles and eating disorders. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 18, 728–735. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01723.x.

Magnavita, J. J. (2012). Advancing clinical science using system theory as the framework for expanding family psychology with unified psychotherapy. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 1, 3–13. doi:10.1037/a0027492.

Mallinckrodt, B., Abraham, W. T., Wei, M., & Russell, D. W. (2006). Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 372–378. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.372;10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.372.supp.

Maloney, M., McGuire, J., & Daniels, S. (1988). Reliability testing of a children’s version of the eating attitudes test. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 5, 541–543. doi:10.1097/00004583-198809000-00004.

Manassis, K., Owens, M., Adam, K., West, M., & Sheldon-Keller, A. (1999). Assessing attachment: Convergent validity of the adult attachment interview and the parental bonding instrument. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 33, 559–567. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00560.x.

Martínez-González, M., Gual, P., Lahortiga, F., Alonso, Y., de Irala-Estévez, J., & Cervera, S. (2003). Parental factors, mass media influences, and the onset of eating disorders in a prospective population-based cohort. Pediatrics, 111, 315–320. doi:10.1542/peds.111.2.315.

McDonald, R., & Grych, J.H. (2006). Young children's appraisals of interparental conflict: Measurement and links with adjustment problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 88–99. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.88.

McEwen, C., & Flouri, E. (2009). Fathers’ parenting, adverse life events, and adolescents’ emotional and eating disorder symptoms: The role of emotion regulation. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 18, 206–216. doi:10.1007/s00787-008-0719-3.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus version 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., Hannan, P. J., Beuhring, T., & Resnick, M. D. (2000). Disordered eating among adolescents: Associations with sexual/physical abuse and other familial/psychosocial factors. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28, 249–258. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(200011)28:3<249:AID-EAT1>3.0.CO;2-H.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Wall, M., Guo, J., Story, M., Haines, J., & Eisenberg, M. (2006). Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: How do dieters fare 5 years later? Journal of American Dietetic Association, 106, 559–568. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.003.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Wall, M., Larson, N. I., Eisenberg, M. E., & Loth, K. (2011). Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of American Dietetic Association, 111, 1004–1011. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012.

Parker, G., Tupling, H., & Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52, 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02487.x.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.

Rhoades, K. A. (2008). Children’s responses to interparental conflict: A meta-analysis of their associations with child adjustment. Child Development, 79, 1942–1956. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01235.x.

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Schermerhorn, A. C., & Cummings, E. M. (2007). Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: Evaluation of the parenting process model. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1118–1134. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00436.x.

Shore, R. A., & Porter, J. E. (1990). Normative and reliability data for 11–18 year olds on the eating disorder inventory. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 201–207. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199003)9:2<201:AID-EAT2260090209>3.0.CO;2-9.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422.

Smolak, L., & Levine, M. (1994). Psychometric properties of the children’s eating attitudes test. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16, 275–282. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199411)16:3<275:AID-EAT2260160308>3.0.CO;2-U.

Snoek, H. M., Van Strien, T., Janssens, J. M. A. M., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2007). Emotional, external, restrained eating and overweight in Dutch adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48, 23–32. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00568.x.

Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Cachelin, F. M. (1999). Body image concerns and disordered eating in adolescent girls: Risk and protective factors. In N. G. Johnson, M. C. Roberts, & J. Worell (Eds.), Beyond appearance: A new look at adolescent girls (pp. 85–108). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sturge-Apple, M. L., Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. M. (2006). Hostility and withdrawal in marital conflict: Effects on parental emotional unavailability and inconsistent discipline. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 227–238. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.227.

Suisman, J. L., Alexandra Burt, S. S., McGue, M., Iacono, W. G., & Klump, K. L. (2011). Parental divorce and disordered eating: An investigation of a gene-environment interaction. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(2), 169–177. doi:10.1002/eat.20866.

Swanson, S., Crow, S., LeGrange, D., Swendsen, J., & Merikangas, K. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Archives of General Psychology, 68, 714–723. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22.

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Troxel, W. M., & Matthews, K. A. (2004). What are the costs of marital conflict and dissolution to children’s physical health? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7, 29–57. doi:10.1023/B:CCFP.0000020191.73542.b0.

Turner, H. M., Rose, K. S., & Cooper, M. J. (2005). Parental bonding and eating disorder symptoms in adolescents: The mediating role of core beliefs. Eating Behaviors, 6, 113–118. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.08.010.

van Strien, T., Frijters, J. E. R., Bergers, G. P. A., & Defares, P. B. (1986). The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5, 295–315. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:2<295::AID-EAT2260050209>3.0.CO;2-T.

Wade, T. D., Bulik, C. M., & Kendler, K. S. (2001). Investigation of quality of the parental relationship as a risk factor for subclinical bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 30, 389–400. doi:10.1002/eat.1100.

Wade, T. D., Gillespie, N., & Martin, N. G. (2007). A comparison of early family life events amongst monozygotic twin women with lifetime anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or major depression. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 679–686. doi:10.1002/eat.20461.

Zimet, D. M., & Jacob, T. (2001). Influences of marital conflict on child adjustment: Review of theory and research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 4, 319–335. doi:10.1023/A:1013595304718.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blodgett Salafia, E.H., Schaefer, M.K. & Haugen, E.C. Connections Between Marital Conflict and Adolescent Girls’ Disordered Eating: Parent–Adolescent Relationship Quality as a Mediator. J Child Fam Stud 23, 1128–1138 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9771-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9771-9