Abstract

On a sample of 313 nine- through 16-year-old Spanish children this study explored the question: Is the relation between paternal versus maternal acceptance and the psychological adjustment of offspring significantly affected by the level of interpersonal power and/or prestige of each parent within the family? The relationship between perceived parental acceptance and children’s psychological adjustment depends on which parent was perceived by children to have higher interpersonal power or prestige than the other. This trend was especially strong in families when mothers were perceived to have both higher power and higher prestige than fathers. The strongest overall contribution to children’s adjustment, however, was made in families where fathers were perceived to have both the highest power and the highest prestige.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing body of research shows that perceived paternal rejection is often more strongly implicated than perceived maternal rejection in a variety of negative offspring outcomes, including substance abuse, depression and depressed affect, behavior problems, and conduct disorder (Rohner and Britner 2002). On the other hand, evidence also suggests that perceived paternal acceptance is often more strongly implicated than perceived maternal acceptance in such positive developmental outcomes as offspring’s sense of well-being in young adulthood (Rohner and Veneziano 2001). Supporting this conclusion is a pancultural meta-analysis of 19,511 respondents from 22 nations on five continents which demonstrated that for children the mean weighted effect size of the correlation between perceived paternal acceptance and psychological adjustment was significantly stronger than the mean weighted effect size of the correlation between perceived maternal acceptance and psychological adjustment (Khaleque and Rohner 2011).

From this evidence it seems clear that children’s perceptions of their fathers’ acceptance sometimes has developmental implications far beyond those traditionally expected. Some studies, however, conclude that children’s perceptions of maternal acceptance are more strongly implicated than perceived paternal acceptance in both positive and negative outcomes (Rohner and Veneziano 2001). At this time it is unclear why the influence of offspring’s perceptions of one parent’s acceptance may be significantly greater than the other parent. Emerging evidence suggests, however, that children’s perceptions of differences in their fathers’ and mothers’ interpersonal power and prestige within the family may influence the degree to which offspring perceive their parents to be accepting as well as influence the level of offspring’s psychological adjustment (Wentzel and Feldman 1996).

Interpersonal Power and Prestige

At this point it is important to clarify the conceptual meaning of interpersonal power and prestige as used in the International father acceptance-rejection project (IFARP), of which this study is a part. All studies in the IFARP are designed to explore the differential impact of perceived paternal versus maternal acceptance on the psychological adjustment of offspring in the context of perceived parental interpersonal power and prestige. In these studies interpersonal power is defined as a person’s ability to influence the opinions or behavior of others (see also Bruins 1999; Keltner et al. 2003; Wentzel and Feldman 1996). The more individuals are able to do this, the more interpersonal power they have. Interpersonal power as defined here is distinguished from authority, and is acquired only through interpersonal interactions between two or more individuals. Authority, on the other hand, is institutionalized power (Weber 1947). It is usually associated with status, which is an institutionally defined social position that can be identified independently of its occupant. Whereas an individual acquires authority solely by occupying a particular position or status, interpersonal power is acquired only through an individual’s personal interactions with others. It is not necessarily associated with any status. Interpersonal power is revealed, for example, when children perceive one parent as having opinions, beliefs, or attitudes that influence them more often than the opinions, beliefs, or attitudes of the other parent. In effect, the higher power parent is seen by offspring as typically having better ideas for solving problems, for making family-related decisions, or for guiding discussions related to day-to-day activities.

Prestige is defined here as social rewards—signs of social approval, esteem, respect, admiration, or being highly regarded by other members of the group (e.g., a family). It is distinguished from liking (Homans 1961: 299–300), but in some situations the two are strongly correlated. Usage of the concept prestige in this context is consistent with Homans’ concept of esteem: “The greater the total reward in expressed social approval a man receives from other members of the group, the higher is the esteem in which they hold him” (Homans 1961: 149). Within the context of the family, prestige is revealed when children personally admire, respect, or hold one parent in higher regard than the other parent.

According to many small group behavior sociologists (Berger and Webster 2006; Dornbusch et al. 1962; Homans 1961), power and prestige are usually linked in stable small groups, at least in experimentally controlled laboratory studies. That is, individuals of high interpersonal power in these studies also tend to be individuals of high prestige, and vice versa. Power and prestige also tend to be distributed unevenly throughout experimental groups. Hence no two individuals are perceived to share the same amount of either. Consequently members of experimental groups may be ranked in both a power and a prestige structure. And the two structures typically tend to be equilibrated or congruent in most experimentally controlled, stable small groups, leading to the concept of a power-prestige structure as distinguished from power and prestige.

Until now, little attention has been paid to the influence of interpersonal power and prestige on children’s development or on family functioning. Family systems theory (Minuchin 1985), however, is an exception to this conclusion. For family systems theorists and practitioners, power—along with family cohesion (i.e., warmth and low levels of hostility among family members)—is a fundamental dimension of family relationships (Gehring et al. 1990). Beyond this, recent research by Huo and Binning (2008) and Huo et al. (2010) demonstrates that feelings of respect affect important aspects of group functioning as well as group-members’ psychological well-being.

More to the point for the purposes of this study, Chyung (2010) found that high prestige fathers in Korea tended to be perceived by adolescent daughters (but not sons) as being significantly more loving than high prestige mothers. But in Croatia, Glavak-Tkalić (2010) found that adolescent sons as well as daughters perceived high power and prestige fathers to be significantly more loving (accepting) than mothers. Beyond this, Khaleque et al. (2010) found in a sample of 200 Bangladeshi young adults that fathers (but not mothers) who were perceived by adult offspring to have the most interpersonal power and prestige within the family were also perceived by the offspring to be significantly more accepting than were fathers with less perceived power and prestige. Moreover, high power and prestige fathers also tended to have significantly greater impact on the psychological adjustment of both adult sons and daughters than did fathers with less power and prestige. This effect was especially strong for daughters. Offspring’s perceptions of maternal power and prestige, however, did not influence either sons’ or daughters’ perceptions of maternal acceptance or offspring’s self-reported psychological adjustment.

Consistent with this body of literature and with the overall objectives of the IFARP, the study reported here explores the differential contribution of perceived paternal versus maternal acceptance to the psychological adjustment of Spanish youths under varying conditions of perceived parental interpersonal power and prestige. More specifically, we ask: Is the relation between perceived paternal versus maternal acceptance and the psychological adjustment of offspring significantly affected by offsprings’ perceptions of interpersonal power and/or prestige of each parent within the family? We ask this question because it seems reasonable to expect that children are likely to pay more attention to and therefore to be more influenced by whichever parent they perceive to have higher power and/or prestige. Accordingly, it seems plausible to expect that children’s perceptions of parental acceptance will be affected by these perceptions. Insofar as this is true, then we expect that children’s overall psychological adjustment will also be affected.

Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory

This expectation is derived from parental acceptance-rejection theory (PARTheory) and evidence about the pancultural association between perceived parental acceptance and children’s psychological adjustment (Khaleque and Rohner 2002). That is, PARTheory postulates and pancultural evidence supports the hypothesis that the psychological adjustment of children everywhere—regardless of differences in culture, ethnicity, language, race, gender, or other such defining conditions—tends to be affected in the same way when they perceive themselves to be accepted or rejected by their parents or other attachment figures. In particular, rejected children tend to develop a specific constellation of personality dispositions called the acceptance-rejection syndrome (Rohner 2004). This syndrome includes issues of anger, hostility, aggression, passive aggression, or problems with the management of hostility and aggression; dependence or defensive independence depending on the form, frequency, severity, and timing of perceived rejection; negative self-esteem; negative self-adequacy; emotional instability; emotional unresponsiveness, and negative worldview.

Collectively, these seven personality dispositions constitute one measure of psychological maladjustment. Beyond this, the syndrome also includes issues of anxiety, insecurity, and cognitive distortions (negative mental representations). The first seven dispositions, however, were the ones identified originally in PARTheory (Rohner 1986). As a result, the vast portion of PARTheory evidence deals with them. Accordingly they constitute the measure of psychological adjustment used in this research too.

Objective of This Research

With these thoughts in mind the objective of this research was—as noted earlier—to explore the question: Is the relation between paternal versus maternal acceptance and the psychological adjustment of offspring significantly affected by the offspring’s perceptions of interpersonal power and prestige of each parent?

Method

Participants

Three hundred and thirteen 9- through 16-year-old children (53 % girls) were randomly recruited from four schools which were themselves randomly selected from all primary and secondary schools in the Madrid metropolitan area of Spain. The mean age of participants was 12.05 years (SD = 2.08 years). Ninety-seven percent of them were White European Catholics. All went to mixed-sex public schools, and all were the biological offspring of their resident parents. The majority of the fathers (95 %) and mothers (74 %) were long-term employed in skilled and semi-skilled jobs. Sixty-four percent of the mothers and 67 % of fathers held undergraduate or postgraduate degrees.

Measures

Index of Parental Power and Prestige (Rohner 2008). Interpersonal power was measured by children’s response to the question “Who in your family usually has the best ideas that other family members follow? Your mother or your father?” Perceived prestige was measured by children’s response to the question “Who do you personally admire or respect more in your family? Your mother or your father?” These items were designed to assess youths’ overall perceptions of their parents’ interpersonal power and prestige. They were not intended to be domain specific.

From these two questions four categories of responses were identified: mothers higher power than fathers, fathers higher power than mothers, mothers higher prestige than fathers, and fathers higher prestige than mothers. Additionally, from these four categories of responses, four paired aggregates of responses (i.e., status groupings) were identified: mothers both higher power and higher prestige than fathers; mothers higher power but lower prestige than fathers; fathers both higher power and higher prestige than mothers; and, fathers higher power but lower prestige than mothers.

Validity of responses on the 2-item index of interpersonal power and prestige is provided by Lloyd and Moore’s (2011) analysis of the relation between the Index and a newly created 10-item parental power-prestige questionnaire (3PQ; Rohner 2011). Their analysis showed excellent agreement between the 5-item interpersonal power subscale (e.g., “Who usually has opinions that influence you the most?” “Who usually has the best ideas for solving problems?”) and participants’ responses on the single interpersonal power question used in this research. Similarly, agreement was good between the 5-item prestige subscale of the 3PQ (e.g., “Who do you personally respect more?” “Who do you personally hold in higher regard?”) and participants’ responses on the single parental prestige question used in this research. The Lloyd and Moore study was based on a sample of 274 respondents. That study showed an alpha of .84 for the Power scale on the 3PQ, and an alpha of .91 for the Prestige scale.

Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (Child PARQ: Father Version and Mother Version; Rohner 2005). Children responded to the short form of the mother and father versions of the Child PARQ. The two versions are identical except in their reference to mothers’ versus fathers’ behavior. Both measures contain the same 24 items, and both contain the same four scales that assess perceived maternal or paternal warmth/affection (e.g., Says nice things about me), hostility/aggression (e.g., Punishes me severely when she is angry), indifference/neglect (e.g., Pays no attention to me), and undifferentiated rejection (e.g., Lets me know I’m not wanted). Taken together these four scales compose the total PARQ score which is an overall measure of perceived parental acceptance-rejection. The questionnaire is keyed in the direction of perceived rejection after reverse scoring the warmth/affection scale to create a measure of perceived coldness and lack of affection. Individuals respond to items such as these on a 4-point Likert scale from (4) almost always true to (1) almost never true. Total scores range from a low of 24 (maximum perceived acceptance) to a high of 96 (maximum perceived rejection). Evidence regarding the reliability and validity of the PARQ has been found to be excellent. Scores at or below 60 reveal that respondents perceive qualitatively more acceptance than rejection. Evidence also shows the appropriateness of combining the four scales to create a total score. Coefficient alphas in this study were .97 for mothers, and .88 for fathers.

Personality Assessment Questionnaire (Child PAQ; Rohner and Khaleque 2005). Children assessed their own psychological adjustment by responding to the Child PAQ. This questionnaire contains seven 6-item scales. Youths respond to the items on a four point Likert scale. Responses range from (4) almost always true through (1) almost never true. Scales are designed to measure the following personality dispositions: hostility/aggression (e.g., “I want to hit something or someone”); dependence (e.g., “I like my parents to give me a lot of attention”), negative self-esteem (e.g., “I feel I am no good and I never will be any good”), negative self-adequacy (e.g., “I feel I cannot do things well”), emotional unresponsiveness (e.g., “It is hard for me to show the way I really feel to someone I like”), emotional instability (e.g., “I get upset when thing go wrong”), and negative worldview (e.g., “I see life as full of dangers”). Taken together the 42 PAQ items compose the total score used in this study. The PAQ was originally designed in such a way that its total score was intended to be a measure of overall psychological adjustment of the form that PARTheory predicts is universally associated with the experience of interpersonal acceptance-rejection. Scores at or below 104 on the Child PAQ reveal the presence of psychological adjustment (versus maladjustment). The measure has been shown to have excellent reliability and validity for use in international research (Rohner and Khaleque 2005). In this study Cronbach’s alpha for the total score was .76.

Procedures

The research was approved by the first author’s institutional review board. Parents of the children provided written informed consent. Additionally, permission to conduct the research was granted by the Director of each school as well as by involved teachers. Children completed anonymously the questionnaires described above in a single 90-min group session.

As noted earlier, interpersonal power and prestige tend to be equilibrated in most experimentally controlled, stable small groups. That is, individuals’ perceived prestige-ranking within stable experimental groups tends to be congruent with their perceived interpersonal power-ranking within the groups. This tendency has not been studied, however, within the naturalistic context of families. Accordingly, prior to beginning analyses of the major questions asked in this research, we tested whether children’s perceptions of parental power was significantly related to their perceptions of parental prestige. A cross tabulation showed that power and prestige rankings were not significantly related (χ2(1) = 2.35, exact significance, p = .11). As a result all analyses were conducted separately for interpersonal power and for prestige. No age group differences were found for power (χ 2(1) = 1.06, exact significance, p = .34) and for prestige (χ 2(1) = .06, exact significance, p = .06).

Data Analysis Plan

The first step in the analysis was to determine by gender of child the mean level of perceived maternal and paternal acceptance as well as the mean level of youth’s psychological adjustment. Analyses were also completed to determine if there were sex differences in these variables. At the same time a determination was made of the percent of fathers versus mothers who were perceived by youths to have higher interpersonal power and higher prestige. Children who failed to make an interpersonal power choice or a prestige choice were treated as missing data. An analysis of children in these subsamples showed that they were not significantly different from the larger samples in terms of sex, SES, age, or level of dependent variables. Subsequently an intercorrelation matrix was created to explore levels of association among substantive variables. Finally, a series of multiple regression analyses were completed in order to assess the extent to which perceived maternal and/or paternal acceptance made unique contributions to children’s psychological adjustment in the various power/prestige conditions.

Results

Results showed that 53 % of the children perceived their mothers to have higher interpersonal power than fathers, whereas 47 % perceived their fathers to have higher interpersonal power. Similarly, 57 % of the children perceived their mothers to have higher prestige than their fathers, whereas 43 % perceived their fathers to have higher prestige. Moreover, as shown in Table 1, both boys and girls tended to perceive their parents (both mothers and fathers) to be quite loving (accepting). This fact notwithstanding, children of both sexes also tended to perceive their fathers to be somewhat more loving than their mothers (boys: t(145) = 3.04, p < .001; girls: t(164) = 4.89, p < .001). Finally, both boys and girls tended to self-report fairly positive psychological adjustment. Because none of the sex differences in perceived acceptance or psychological adjustment was statistically significant, all further analyses were completed using the total sample Similarly, because analyses involving younger youths (i.e., ages 9–12) versus older youths (i.e., ages 13–16) yielded similar results, all subsequent analyses were pooled across age. Doing this allowed us to maintain a large enough sample size to assure adequate statistical power for effectively testing the principal research questions in this study.

Intercorrelations displayed in Table 2 reveal that, as expected, both perceived maternal acceptance and perceived paternal acceptance were significantly correlated with the psychological adjustment of children regardless of which parent was perceived to have higher power or higher prestige. But because perceived maternal acceptance and paternal acceptance were also strongly correlated with each other in all four status groupings, it was not possible to tell if both maternal and paternal acceptance made unique (i.e., independent) contributions to children’s psychological adjustment in all conditions.

In order to determine this we completed a series of stepwise multiple regression analyses in the various power/prestige conditions (see Tables 3, 4). All these analyses included maternal and paternal acceptance as the independent variables, and children′s psychological adjustment as the dependent variable. Table 3 shows that perceived maternal and paternal acceptance continued to make a unique contribution to children’s adjustment in all power and prestige conditions except where children perceived their mothers to have higher prestige than their fathers. In that context the unique contribution of paternal acceptance to children’s adjustment was only marginally significant (p = .06). It is worth noting, however, that perceived maternal acceptance and paternal acceptance jointly accounted for only 26 % of the variance in children’s psychological adjustment in families where mothers were perceived to have higher prestige than fathers. This is the lowest R 2 value in Table 3. On the other hand, perceived maternal and paternal acceptance accounted jointly for 36 % of the variance in children’s adjustment in families where fathers were perceived to have higher prestige than mothers. This is the highest R 2 value in Table 3.

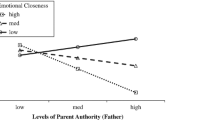

Beyond this, an interesting overall trend emerged. That is, the influence of perceived acceptance on children’s psychological adjustment appeared to be slightly greater depending on which parent was perceived by children to have higher power or higher prestige than the other. That is, the contribution of fathers’ acceptance to children’s adjustment (as shown by the Betas) was slightly greater than mothers’ in families where fathers were perceived to have either higher power or higher prestige than mothers. But the same trend was true for mothers. That is, mothers’ contribution to children’s psychological adjustment tended to be slightly greater than fathers’ in families where mothers were perceived by children to have either higher power or higher prestige. Though these minor differences are consistent across the four power/prestige conditions, they may be conceptually trivial because both perceived maternal and paternal acceptance have a similarly moderate impact on the youth’s self-reported psychological adjustment in all four conditions.

The picture became somewhat more complicated, however, when we asked about the relation between perceived parental acceptance and children’s adjustment in contexts where one parent was perceived to have higher interpersonal power and the other parent was perceived to have higher prestige, or where one parent was perceived to have both higher power and higher prestige than the other. Results of regression analyses of these issues, shown in Table 4, revealed that in families where mothers were perceived to have both higher power and higher prestige than fathers, children’s perceptions of mothers’ acceptance tended to make a greater contribution to children’s adjustment than did fathers’ acceptance. However, in families where fathers were perceived to have both higher power and higher prestige than mothers, children’s perceptions of fathers’ acceptance made a greater contribution to children’s psychological adjustment than any other power/prestige combination. In fact, the overall contribution of parental acceptance to children’s adjustment was greatest in families where fathers were perceived to have the highest power and highest prestige, as shown by the fact that this category of parent was associated with 39 % of the variance in children’s adjustment. Finally, the contribution of mothers’ acceptance to offsprings’ psychological adjustment tended to be greater than that of fathers in families where one parent—either one—was perceived by offspring to have higher power than the other but the other parent was perceived to have higher prestige.

Discussion

This study is the first of its kind to explore the differential contribution of perceived paternal versus maternal acceptance to the psychological adjustment of Spanish youths under varying conditions of perceived parental power and prestige. In particular, we ask whether the relation between perceived paternal versus maternal acceptance and the psychological adjustment of offspring is significantly affected by offsprings’ perceptions of interpersonal power and/or prestige of each parent within the family. Results of intercorrelation analyses shows—as expected—that both perceived maternal acceptance and perceived paternal acceptance are significantly correlated with the psychological adjustment of both boys and girls—regardless of which parent has higher power or higher prestige.

Multiple regression analyses, however, allowed for a more nuanced view of these relations. More specifically, these analyses show that both perceived maternal and paternal acceptance make unique or independent contributions to children’s adjustment in all power/prestige conditions except perhaps where children perceive their mothers to have higher prestige than their fathers. In that context the unique contribution of perceived paternal acceptance to children’s adjustment becomes only marginally significant in Spanish families. Additional research is required to determine if this conclusion might be an idiosyncratic peculiarity of this specific sample, or if it might be theoretically meaningful in a broader context.

Beyond this, however, several important trends emerged in this study. First, results of multiple regression analyses show that the contribution of fathers’ acceptance to children’s adjustment is greater than mothers’ in families where fathers are perceived by children to have either higher interpersonal power or higher prestige than mothers. However, results also show the opposite to be true. That is, the contribution of mothers’ acceptance to children’s adjustment tends to be greater than fathers’ in families where mothers are perceived to have either higher interpersonal power or higher prestige than fathers.

A striking result of the study is the fact that the relation between children’s perceptions of parental acceptance and children’s adjustment is most affected in families where one parent is perceived to have both higher power and higher prestige than the other parent. But in families where one parent is perceived to have higher power than the other parent–but the other parent is perceived to have higher prestige–the relation between perceived parental acceptance and offsprings’ adjustment is more affected by perceived maternal acceptance than by paternal acceptance. Even though these differences are consistent across all four power/prestige conditions, they may be conceptually trivial because both perceived maternal acceptance and paternal acceptance have a similarly moderate impact on children’s psychological adjustment in all four power/prestige conditions. Future research will help determine if these minor differences are stable and theoretically important. At this point, however, interpretation about their meaning is risky because the sample sizes on which they are based are small. Moreover, it is important to note that the large confidence intervals reported in Tables 3 and 4 suggest the possibility that the difference in Betas between mothers and fathers is not truly significant. It is likely, however, that the large confidence intervals result from low heterogeneity in the sample.

All these results based on a dimensional approximation through correlational methods may be showing just a portion of the nature of the nomological network of the variables. Future studies should explore a categorical approach based on a criterion referenced analysis that provides complementary results in order to clarify how the variables are related. Related to this is the limiting fact that this study is based on a measure of interpersonal power and prestige that is composed of only two questions, namely “Who in your family usually has the best ideas that other family members follow?” and “Who do you personally admire or respect more in your family?” Research based on a newly developed 10-item parental power-prestige questionnaire (3PQ), however, suggests that results from the 2-item forced-choice measure used here correspond closely with results from a newer 10-item measure (Lloyd and Moore 2011). Though an imperfect estimate of the validity of the single-item format, the close agreement between the two sets of measures does provide encouraging evidence that items in the forced-choice format are measuring what they are purported to measure. In addition, results of future research using the 3PQ will help to assess a question that cannot be addressed in this study. Specifically, what—if any–impact do parental interpersonal power and prestige have on the association between perceived parental acceptance and offspring adjustment in contexts where parents are perceived to be coequal in interpersonal power and prestige? Given the forced-choice nature of the 2-item measure, we were unable to explore that question. Finally, because this research is cross-sectional in design we cannot make any causal attributions about the influence of perceived interpersonal power or prestige as being important mediators or moderators of the relationship between perceived parental acceptance and offspring adjustment. Future studies will address these issues.

Despite these limitations it seems likely that, as expected, children’s perceptions of differences between their mothers’ versus their fathers’ interpersonal power and prestige are associated in systematic ways with variations in the relation between perceived parental acceptance and offsprings’ psychological adjustment. We speculate that this is true because children may pay somewhat closer attention to the behavior of whichever parent they perceive to have higher power and/or prestige than the other parent. Insofar as this is true, we expect that the behavior of the higher power/prestige parent will generally have a greater impact on children than will the behavior of the lower power/prestige parent. Given the fact that children’s perceptions of parental acceptance-rejection tend panculturally to be associated with the specific form of psychological adjustment measured in this study (Khaleque and Rohner 2002; Rohner and Khaleque 2010), it is perhaps not surprising that the children’s perceptions of differences between maternal versus paternal power and prestige are systematically linked to the relation between perceived parental acceptance and youths’ adjustment.

Finally, evidence provided in this article makes even more compelling the call by Silverstein and Phares (1996) to transform the dominant theoretical paradigm in the social sciences from a dyadic mother–child to a triadic father-mother–child or larger systems model. This transformation would include a paradigm shift in clinical and other programs to automatically include fathers as well as mothers in all parenting matters. In addition, the transformation would recognize the need to explore social policy implications of research showing the powerful influence of father love (acceptance) in relation to mother love in varying familial contexts where the impact of one parent’s love-related behaviors tends to be greater than the impact of the other parent’s.

References

Berger, J., & Webster, M, Jr. (2006). Expectations, status, and behavior. In P. J. Burke (Ed.), Contemporary social psychological theories (pp. 268–300). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bruins, T. (1999). Social power and influence tactics: A theoretical introduction. Journal of Social Issues, 55, 7–14.

Chyung, Y-J. (2010). International father acceptance-rejection project report from Korea. Unpublished manuscript.

Dornbusch, S. M., Zelditch, M., Berger, J., Cohen, A. H., & Scott, W. (1962). A proposal for the study of authority structures and evaluations. Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California.

Gehring, T., Wentzel, K., Feldman, S., & Munson, J. (1990). Conflict in families of adolescents: The impact on cohesion and power structures. Journal of Family Psychology, 3, 290–309.

Glavak-Tkalić, R. (2010, July). Relations between fathers’ power, prestige, acceptance, and involvement and psychological adjustment among Croatian adolescents. Paper presented at the meeting of the international society for interpersonal acceptance and rejection, Padua, Italy.

Homans, G. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc.

Huo, Y. J., & Binning, K. R. (2008). Why the psychological experience of respect matters in group life: An integrative account. Social Psychology and Personality Compass, 2, 1570–1585.

Huo, Y. J., Binning, K. R., & Molina, L. (2010). Testing an integrative model of respect: Implications for social engagement and well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 200–212.

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110, 265–284.

Khaleque, A., & Rohner, R. P. (2002). Perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: A meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 64, 54–64.

Khaleque, A., & Rohner, R. P. (2011). Pancultural associations between perceived parental acceptance and psychological adjustment of children and adults: A meta-analytic review of worldwide research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0022022111406120.

Khaleque, A., Rohner, R. P., & Shirin, A. (2010, July). Impact of fathers’ power, prestige, and love in Bangladeshi families. Paper presented at the meeting of the international society for interpersonal acceptance and rejection, Padua, Italy.

Lloyd, J., & Moore, K. (2011). Analysis of the parental power-prestige questionnaire (3PQ) and its association with the two-item measure of parental power and prestige. Unpublished manuscript, University of Chester, Chester, U.K.

Minuchin, P. (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56, 289–302.

Rohner, R. P. (1986). The warmth dimension: Foundations of parental acceptance-rejection theory. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Rohner, R. P. (2004). The parental “acceptance-rejection syndrome”: Universal correlates of perceived rejection. American Psychologist, 59, 827–840.

Rohner, R. P. (2005). Parental acceptance-rejection questionnaire (PARQ): Test manual. In R. P. Rohner & A. Khaleque (Eds.), Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection (4th ed., pp. 43–106). Storrs, CT: Rohner Research Publications.

Rohner, R. P. (2008). Index of parental power and prestige. Unpublished manuscript. University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Rohner, R. P. (2011). The parental power and prestige questionnaire (3PQ). Storrs, CT: Rohner Research Publications.

Rohner, R. P., & Britner, P. A. (2002). Worldwide mental health correlates of parental acceptance-rejection: Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Cross-Cultural Research, 36, 16–47.

Rohner, R. P., & Khaleque, A. (2005). Personality assessment questionnaire (PAQ): Test manual. In R. P. Rohner & A. Khaleque (Eds.), Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection (4th ed., pp. 187–226). Storrs, CT: Rohner Research Publications.

Rohner, R. P., & Khaleque, A. (2010). Testing central postulates of parental acceptance-rejection theory (PARTheory): A meta-analysis of cross-cultural studies. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 3, 73–87.

Rohner, R. P., & Veneziano, R. A. (2001). The importance of father love: History and contemporary evidence. Review of General Psychology, 5, 382–405.

Silverstein, L. B., & Phares, V. (1996). Expanding the mother-child paradigm: An examination of dissertation research, 1986–1996. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 39–53.

Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization. (Trans: Henderson, A. M., & Parsons, T.). New York: The Free Press.

Wentzel, K. R., & Feldman, S. S. (1996). Relations of cohesion and power in family dyads to social and emotional adjustment during early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6, 225–244.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carrasco, M.A., Rohner, R.P. Parental Acceptance and Children’s Psychological Adjustment in the Context of Power and Prestige. J Child Fam Stud 22, 1130–1137 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9675-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9675-0