Abstract

Parents’ view of the quality of early childhood education and care services has mostly been addressed from the perspective of customer satisfaction. This study investigated parents’ view within a more comprehensive framework in which parents’ values of child care, their evaluations of their child’s experience at the service and overall satisfaction with the service were considered. In particular, the study explored how values and evaluations are related and how they affect overall satisfaction. A questionnaire including a total of 96 items was filled in by 2,936 parents of children attending infant-toddler day-care centres in Rome, Italy. Parents were asked to express their values regarding child care quality and evaluate specific aspects of their experience. Parents’ perspectives of both their child’s and their own experience of childcare services were addressed separately. Two principal component analyses were performed in order to identify latent dimensions underlying parents’ values about child care quality and their evaluations of the service attended by their child. The relationships between the different dimensions of value, evaluation, and overall satisfaction with their child’s and their own experience were explained through two path models, in which values predict evaluations and these, in turn, predict overall satisfaction. Results showed that parents have a multi-faceted view of child care quality and confirm the relevance of taking into account their point of view in an analysis of the quality of early childhood education services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many studies of parents’ view of child care quality have investigated the determinants of parent choice of child care, i.e. the factors influencing parents decision-making for non-maternal care and specific child care arrangements. A major issue discussed in these studies is whether parent choice of a particular type of care (centre-based, home-based, or provided by a relative) is due to family characteristics or to child care quality features, such as the education and attitudes of caregivers, environment/equipment or programmes. Availability, accessibility and cost emerged as the most important variables in parent decision-making, though they were found to vary according to family characteristics such as income, education, and ethnicity. Availability and accessibility of arrangements emerged consistently as key determinants in the choice of all families (Davis and Connelly 2005; Johansen et al. 1996; Musatti 1993; Noble 2007; Singer et al. 1998), while cost was found to be a dominant aspect for low-income families (Leslie et al. 2000; Peyton et al. 2001). In all the studies, the features of child care arrangements that affected parent choice varied according to the child’s age: in the case of infants and toddlers, parents considered caregivers’ warmth towards the child as the most important element, while the parents of pre-schoolers were more focused on the curriculum and caregivers’ level of education.

Also parent beliefs about mother’s employment and non-maternal care were found to influence parental choice (Early and Burchinal 2001; Pungello and Kurtz-Costes 1999, 2000). Further studies showed that a plurality of other elements contribute to the choice, such as parent values and their daily schedule, as well as various features of the child care arrangements (Emlen et al. 1999; Kensinger Rose and Elicker 2008). Kim and Fram (2009) found that mothers’ education, income, and beliefs about the developmental needs of the child interact in determining choice of child care.

Other studies investigated parent satisfaction with the child care choice they made, its variability and reasons Most studies found a high rate of satisfaction, though it varied according to family income and parent motivations in making their choice (Peyton et al. 2001), as well as to mothers’ attitudes and beliefs (Barnes et al. 2006). Leach et al. (2006) argued that parents’ satisfaction might be enhanced by a feedback effect of the choice made. Furthermore, many studies showed that parents report high levels of satisfaction with their child care arrangements even when its quality was assessed as mediocre by early childhood experts. Cryer and Burchinal (1997) and Cryer et al. (2002) submitted a questionnaire that matched the ECERS (Harms and Clifford 1980) and ITERS (Harms et al. 1990) scales to parents using a child care service. Parents valued the same aspects that early childhood professionals believed to constitute quality child care, though they overestimated and prioritised them differently. According to the authors these findings result from the scarce information parents have about appropriate child care practices and their implementation, which they are able to observe only at drop off and pick up times. Other authors have also argued that the discrepancy between parent and professional views is due to the fact that parents are not well informed (Helburn and Howes 1996; Murray et al. 2007; Peyton et al. 2001).

An alternative interpretation can be advocated, i.e. that parents have a specific view of the quality of child care services. This interpretation has been proposed by Katz (1993) and it underlies also the documents issued by the Child Care Network of the European Commission (1991, 1996) stating that parents should participate in defining and evaluating the quality of early childhood services. According to Emlen et al. (2000) “parents can tell us, reliably and with some validity, about the child care they have and what it is like (p. 22)” and the discrepancy between parent and professional ratings of quality can be partially explained by their focus on different elements. The authors measured parent’s point of view on child care quality and their overall satisfaction with their child care arrangements through separate scales. Although parents valued caregivers’ professional competences and behaviours, and the quality of the physical environment, they placed particular importance on their own relationship with caregivers. The weak correlation between actual quality and satisfaction ratings provided evidence of their capacity for giving reliable evaluations of child care quality, separate from their satisfaction with it. Several studies suggest that parents have an articulated view about child care quality (Ceglowski 2004; Ceglowski and Bacigalupa 2002; da Silva and Wise 2006). Although they share with professionals a general understanding of the components of child care quality, such as attention to cultural diversity and individual needs, health and safety of the children, and caregivers’ warmth and sensitivity, they often prioritise other aspects, such as flexibility and communication with caregivers. Gamble et al. (2009) showed that parents possess coherent sets of beliefs about the important characteristics of child care arrangements, according to which the attention to children’s developmental needs plays a central role.

Katz (1993) claimed that parent relationships with the child care service attended by their child also have to be explored in order to gain a better understanding of parental views. Larner and Phillips (1994) argued that this relationship is based on positive staff-parents interactions, as well as on the overall capacity of the service to take into account parent concerns about their child’s well-being. Parental involvement in the service attended by their child is considered an important component of service quality by international experts (OECD 2001, 2006; Bennett 2008). In Italian early childhood education provision, paying attention to both a child’s and the parent’s well-being, especially during the first period of attendance at the service, is considered best practice (Mantovani 2007; Musatti 2006). Practices that promote parental participation in the service and caregiver-parent communications were found to have a positive effect on parent satisfaction (Fantuzzo et al. 2006).

All the above considerations suggest that a thorough analysis of parent views on child care quality is needed. Parents cannot be interviewed as mere clients of a service, as proposed in models of customer satisfaction, which understand service quality to be the difference between users’ expectations and evaluations (Zeithaml et al. 1990). Lages and Fernandes (2005) argue that constructs at a high level of abstraction, such as personal values, must be included in investigating user views of service quality. Even more importantly we should take a more comprehensive stance when investigating parent views on such a complex and awkward topic as the quality of early childhood education and care service.

Current Study

This study analysed how parents’ personal values about the quality of early childhood education and care services, and their evaluations of the service experienced are related, and contribute to determining their overall satisfaction, by addressing three related questions. First, we aimed at identifying latent dimensions underlying parent values of child care quality, as well as their evaluations of the service attended. With regard to personal values, which are defined as desirable goals (Schwartz 1992, 1994), we considered the importance parents attribute to the service capacity to meet their child’s and their own needs; moreover, given parents’ concerns and their emotional ambivalence about non-maternal child care, we explored their worries about its undesirable consequences as well. Since the actual experience of the service can have both positive and negative aspects, we explored parent evaluations of the benefits and discomforts experienced with the service. The second question concerns how positive and negative aspects of value and evaluation are related, and how they are related to overall satisfaction. We assumed that parents make experience of the child care service from both their child’s and their own perspective. Given this twofold stance, we explored the relationships between parent values, evaluations, and overall satisfaction with regard to their child’s and their own experience separately. Finally, we explored whether and how parent values, evaluations and overall satisfaction are related to family and child characteristics.

Method

Context, Participants and Procedure

This study was carried out in 2008 by interviewing parents of children under 3 years of age who attended an infant-toddler day care centre (nido) in Rome, Italy. In 2008, the Municipality of Rome supplied a relevant number of municipal or subsidised infant-toddler day care centres, which were the unique out-of-home childcare public provision and catered for 22 % of children in the city. All centres complied with a set of accreditation requirements with homogeneous standards in terms of structural and process quality (group-size, staff-child ratio, teacher training, environmental safety and adequacy). Access procedures to the centres prioritised working mothers and low-income families. Parents paid low fees that varied according to their income.

Since 2005 the Municipality of Rome has used a comprehensive system of evaluation of the subsidised centres that includes assessment from the parent’s point of view. Our study analysed the data collected in 78 accredited and subsidised centres. Through collaboration with the centre staff, 3,241 parents using these centres were contacted and invited to fill in an anonymous paper-and-pencil questionnaire, which was expressly designed for the purpose. The questionnaires were administered at the end of the educational year when 89.7 % of participants had been attending the service for at least 8 months. A total of 2,936 parents (90.6 %) completed the questionnaire.

The Questionnaire

The questionnaire included four sections with a total of 96 items:

Section 1. Child, parents, and family characteristics (13 open-ended or multiple choice items): child’s gender and age, number of siblings, father’s and mother’s age, their birthplace, education, and employment status.

Section 2. Family organisation and child’s daily life (25 multiple choice items): child’s principal caregivers at home, child’s social contacts with relatives and peers, and parent’s motives for choosing the infant-toddler centre as an out-of-home childcare arrangement (family organisation, child’s learning, child’s socialisation, child’s well-being, grandparents’ unavailability, sibling’s positive experience of the centre). Parents were allowed to indicate several motives for their choice.

Section 3. Values of child care quality (19 Likert-type items): parent attribution of importance to different aspects of the service quality with regards children and parents separately, and any worries they had about the child’s physical and psychological well-being and the program quality before attendance.

Section 4. Evaluation of the experience with the service by the child and the parents (37 Likert-type items): child and parent experiences during their first entry into the service, curriculum and educational activities, caregiver behaviour, quality of the environment, arrangements and materials, child’s achievements, parent interactions with caregivers and participation with the service. Two further Likert-type items asked parents to express their overall satisfaction with their own and their child’s experience.

In sections 3 and 4, the item responses ranged from 0 (“Very little/not at all”) to 3 (“Very much”).

Results

Family Characteristics and Child Care Choices

Children were aged from 4 to 60 months (M = 27.10, SD = 7.75) and balanced for gender (males: 51 %). Most of the families had only one child (43.5 %) or two children (41.4 %). The majority of parents were aged between 35 and 39 (mothers: M = 35.81, SD = 4.47; fathers: M = 38.30, SD = 5.06) and their average education was medium–high (mothers: 44.7 % with a high school degree, 38.1 % with a university degree; fathers: 44.8 % with a high school degree, 29.6 % with a university degree). As access procedures ensure priority to working mothers, 70.8 % of mothers were long-term employed and only 4.1 % of mothers reported themselves as unemployed. Only 9.7 % of mothers and 9.4 % of fathers were born in a foreign country.

From section 2 only the item on motives for choosing infant-toddler centre as out-of-home childcare arrangement was analysed. Family organisation and the availability of grandparent were considered together as “Organisational motives”, while child’s learning, and child’s socialisation were both considered “Educational motives”. Most of parents (59.3 %) reported both organisational and educational motives, while 15.1 % had considered only organisational and 18.8 % only educational motives; 6.8 % of answers included other motives. The variability of motives according to child’s and mother’s more relevant characteristics (age, gender, number of siblings; age, birth place, education, employment, respectively) was also explored. Child’s age (Chi-Square = 41.50, df = 3, p < .001), number of siblings (Chi-Square = 29.37, df = 3, p < .001), mother’s education (Chi-Square = 25.68, df = 6, p < .001) and employment (Chi-Square = 33.75, df = 3, p < .001) were found to be significantly associated to child care motives. Residual analyses showed that educational motives were more frequent for children older than two, less educated and unemployed mothers, while organisational motives were associated with child’s younger age, presence of siblings, and mother’s employment.

Parents’ Values About Child Care Quality

In order to identify the dimensions underlying parent values of child care quality we performed a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the items of section 3. For each factor, only items showing a factor loading >.40 were considered. The analysis yielded a 6-factor solution, with Oblimin rotation, explaining 58.3 % of the variance. A weak correlation among all the factors was found, ranging from r = .02 to r = .39. Factor loadings, eigenvalues, and explained variance of the factors are reported in Table 1.

Factor 1, which explained 21.4 % of the variance, represents the importance attributed by parents to the child’s cognitive and social experience within the service. It was labelled “Importance of child’s experience”. Factor 2, which explained 12.6 % of the variance, represents the parent worry that the educational context, considering both caregiver activities and environmental issues, might be inadequate. It was labelled “Worry for educational context”. Factor 3, which explained 7.0 % of the variance, represents the importance attributed by parents to finding a warm and friendly social environment within the service. It was labelled “Importance of parents’ social contacts”. Factor 4, which explained 6.1 % of the variance, represents parent worry that their child may have dysfunctional interactions in the service. It was labelled “Worry for child’s relations”. Factor 5, which explained 6.1 % of the variance, represents parent worry that either their child will have health problems or will undergo psychological suffering when coping with separation from parents. It was labelled “Worry for child’s well-being”. Factor 6, which explained 5.1 % of the variance, represents the importance attributed by parents to participating in the service’s daily life and establishing positive relations and communications with caregivers. It was labelled “Importance of parents-caregivers sharing”. Reliability analyses (Cronbach’s alpha) revealed satisfactory internal consistency only for four of the dimensions (see Table 1). Given the explorative purpose of the study Worry for child’s relations and Worry for child’s well-being were considered in subsequent analyses, though they showed a weak internal consistency.

Analysis of mean aggregate scores of the variables contributing to each factor showed high to moderate levels of parent attributions of importance (Importance of child’s experience: M = 2.51, SD = .45; Importance of parents-caregivers sharing: M = 2.59, SD = .42; Importance of parents’ social contacts: M = 1.57, SD = .77) and, conversely, low to moderate levels of parents’ worries (Worry for child’s relations: M = .15, SD = .37; Worry for educational context: M = .52, SD = .69; Worry for child’s well-being: M = 1.39, SD = .79). Child’s and mother’s characteristics did not show a strong influence on these variables. The number of siblings affected Worry for educational context (F(1, 2,699) = 22.06, p < .001) and Worry for child’s well-being (F(1, 2,872) = 38.49, p < .001): parents with one child expressed a higher level of concern for both aspects. Also mother’s education had a weak influence on Worry for child’s relations (F(2, 2,620) = 29.60, p < .001) and Importance of parents’ social contacts (F(2, 2,814) = 19.40, p < .001): less educated mothers expressed higher levels for both variables.

Parents’ Evaluations of Child Care Quality

A further PCA was performed on the items of section 4. For each factor, items showing a factor loading >.40 were considered. The analysis yielded a 7-factor solution, with Oblimin rotation, explaining 59.4 % of the variance. A moderate correlation among all factors emerged, ranging from r = −.10 to r = .68. Factor loadings, eigenvalues, and explained variance of the factors are given in Table 2.

Factor 1, which explained 33.8 % of the variance, expresses evaluations of the child’s social, emotional and cognitive experience in the service. The factor was labelled “Child’s experience”. Factor 2, which explained 7.2 % of the variance, expresses evaluations of the different sources of parent discomfort with the experience made directly as a parent. The factor was labelled “Parents’ discomfort”. Factor 3, which explained 4.9 % of the variance, expresses judgments on the fit of the centre’s environment for both the child’s and the parent’s needs. The factor was labelled “Quality of environment”. Factor 4, which explained 3.9 % of the variance, expresses parent evaluations of the potential sources of their child’s discomfort in their experience. The factor was labelled “Child’s discomfort”. Factor 5, which explained 3.5 % of the variance, expresses evaluations of the opportunities to participate in centre life and of parent-caregiver interactions. The factor was labelled “Parents’ participation”. Factor 6, which explained 3.3 % of the variance, expresses judgments on caregiver capacities to adjust their behaviour to children’s individual needs, resolve conflicts among children, and support children’s acquisition of autonomy and social rules. The factor was labelled “Caregivers’ behaviours”. Factor 7, which explained 2.8 % of the variance, expresses parent judgments of how they and their child were welcomed at their first entry into the centre. The factor was labelled “Context responsiveness”. Reliability analyses revealed a satisfactory internal consistency for all the dimensions (see Table 2). The analysis of mean aggregate scores of the dimensions showed a positive evaluation of the different facets of the experience in the centre (Child’s experience: M = 2.32, SD = .49; Quality of environment: M = 2.08, SD = .61; Parents’ participation: M = 1.87, SD = .69; Caregivers’ behaviours: M = 2.16, SD = .57; Context responsiveness: M = 2.32, SD = .49); accordingly, scores for factors representing discomfort were low (Parents’ discomfort: M = .16, SD = .37; Child’s discomfort: M = .26, SD = .40).

Again, most child and mother characteristics did not affect these variables. The number of siblings affected parents’ evaluations of Child’s discomfort (F(1, 2,908) = 28.05, p < .001), Caregivers’ behaviours (F(1, 2,901) = 37.62, p < .001) and Context responsiveness (F(1, 2913) = 26.27, p < .001): parents with one child reported a higher level of Child’s discomfort and those with more children evaluated the other two dimensions more highly. Less educated mothers expressed a better evaluation only of Parents’ participation (F(2, 2,814) = 19.40, p < .001).

Overall Satisfaction and Its Determinants

Overall satisfaction of child (M = 2.49, SD = .62) and parents (M = 2.29, SD = .71) experiences in the service showed remarkably high scores and were significantly correlated (r = .73, p < .001, 53 % of common variance). Child’s satisfaction was significantly higher than Parents’ satisfaction (F(1, 2,872) = 457.54, p < .001). Child and mother characteristics showed a weak influence on overall satisfaction. An effect of the number of children on Parents’ satisfaction (F(1, 2,866) = 26.24, p < .001) emerged, with higher levels expressed by parents with more children.

Given the weak influence of child and mother characteristics on parent values, evaluations, and overall satisfaction, we explored only the relationships between values and evaluations in predicting Child’s and Parents’ satisfaction through two path analyses. Preliminarily, we checked for multicollinearity among predictors (see Table 3). We found significant correlations between the three dimensions of importance, the three dimensions of worry, and the seven dimensions of evaluation. Significant correlation also emerged between values and evaluations, while the dimensions of importance and worry were not correlated. Overall, results showed little evidence of multicollinearity, as the highest correlation was between Caregivers’ behaviour and Child’s experience (r = .688, p < .001, 47 % of common variance). All predictors were then included in the analyses.

In the first step, we explored the relationships between parent values and evaluations through a series of regression analyses, in which each dimension of evaluation was considered as the final criterion, and the dimensions of importance and worry were considered as predictors. Table 4 shows that all the dimensions of importance are positive predictors of the dimensions of evaluation referring to positive aspects of the service. The importance of Child’s experience shows the strongest associations, and also negatively influences Parents’ discomfort. The relationship between worries and evaluations is more complex. Worry for educational context showed the strongest influence on evaluations: a negative relationship with all positive aspects of the experience, and a positive relationship with both Child’s and Parents’ discomfort. Worry for child’s well-being was found to negatively affect Child’s experience, Caregivers’ behaviours, and Context responsiveness, and positively Child’s discomfort. Worry for Child’s relations showed the weakest influence on evaluations: a positive influence on Quality of environment and Child’s discomfort, and a negative influence on Parents’ participation.

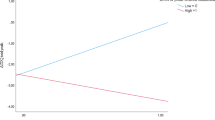

In the second step, we analysed the relationships between values, evaluations and overall Child’s and Parents’ satisfaction. Regression analysis showed that Child’s satisfaction was predicted by dimensions of both value and evaluation (R 2 = .56, F(13, 2,573) = 253.45, p < .001) to different extents. Only two out of six dimensions of value, namely Worry for educational context (β = −.18, p < .001) and Importance of parents’ social contacts (β = −.12, p < .001), showed a significant effect on Child’s satisfaction. Conversely, all the dimensions of evaluation—with the exception of Child’s discomfort (β = −.02, ns)—showed a significant effect on Child’s satisfaction. Mediation analyses showed that Child’s satisfaction was predicted by parent evaluations, while the direct effect of values on satisfaction is weak (see Fig. 1).

When the dimensions of evaluation were included in the model, the relationship between Worry for educational context and Child’s satisfaction (see Fig. 1a), which was found to be significant in the previous regression analysis, emerged to be mediated by the dimensions of evaluation (Sobel Test: z = 9.82, p < .001) and no more significant (β = −.03, ns). The six dimensions of evaluation, namely Child’s experience (β = .35, p < .001), Parents’ discomfort (β = −.13, p < .001), Quality of environment (β = .10, p < .001), Parents’ participation (β = .11, p < .001), Caregivers’ behaviours (β = .06, p < .01), and Context responsiveness (β = .17, p < .001) significantly influenced Child’s satisfaction. The relationship between Importance of parents’ social contacts and Child’s satisfaction (see Fig. 1b) remained significant (β = −.07, p < .01), although it decreased and was found to be partially mediated by the dimensions of evaluation (Sobel Test: z = 12.54, p < .001). Again, the six dimensions of evaluation, Child’s experience (β = .36, p < .001), Parents’ discomfort (β = −.12, p < .001), Quality of environment (β = .11, p < .001), Parents’ participation (β = .13, p < .001), Caregivers’ behaviours (β = .06, p < .01), and Context responsiveness (β = .17, p < .001) significantly influenced Child’s satisfaction.

A similar pattern emerged when considering Parents’ satisfaction. Regression analysis showed that Parents’ satisfaction was influenced by dimensions of both value and evaluation (R 2 = .57, F(13, 2,554) = 259.95, p < .001), but again to different extents. Only the dimensions Worry for educational context (β = −.18, p < .01) and Importance of parents’ social contacts (β = −.17, p < .001), showed a significant influence on Parents’ satisfaction. All the dimensions of evaluation, with the exception of Child’s discomfort (β = −.003, ns), showed a significant effect on Parents’ satisfaction. Mediation analyses showed that Parents’ satisfaction was predicted by their evaluations, while the direct effect of values on satisfaction is weak (see Fig. 2).

When the dimensions of evaluation were included in the model, the relation between Worry for educational context and Parents’ satisfaction (see Fig. 2a) emerged to be mediated by the dimensions of evaluation (Sobel Test: z = 10.21, p < .001) and became non-significant (β = −.03, ns). The Child’s experience (β = .19, p < .001), Parents’ discomfort (β = −.13, p < .001), Quality of environment (β = .15, p < .001), Parents’ participation (β = .30, p < .001), Caregivers’ behaviours (β = .10, p < .001), and Context responsiveness (β = .10, p < .001) dimensions of evaluation showed a significant influence on Parents’ satisfaction. The relationship between Importance of parents’ social contacts and Parents’ satisfaction (see Fig. 2b), although significant (β = −.05, p < .01), decreased, and emerged to be partially mediated by the dimensions of evaluation (Sobel Test: z = 13.61, p < .001). Child’s experience (β = .19, p < .001), Parents’ discomfort (β = −.12, p < .001), Quality of environment (β = .15, p < .001), Parents’ participation (β = .31, p < .001), Caregivers’ behaviours (β = .10, p < .001), and Context responsiveness (β = .10, p < .001) showed a significant influence on Parents’ satisfaction.

Discussion

We identified six dimensions of values of service quality. Three correlated dimensions demonstrate what parents consider to be important for the quality of a child care service, and correspond to themes identified by previous studies (Ceglowski 2004; da Silva and Wise 2006). The dimension of child’s educational experience, which includes new experiences, positive relationships with adults and other children, opportunities for autonomy and the acquisition of social rules, is highly valued (Noble 2007). Parents also value the opportunity to share ideas and experiences with caregivers and, to a lesser extent, the opportunity to socialise with other parents.

Parents clearly distinguish three other correlated dimensions representing potential inadequacies and difficulties for children in the service, which are a source of worry. A key dimension of worry refers to the educational context, in which both care-giving modalities and features of the environment are considered. Two other dimensions concern the child’s social relations—with both caregivers and other children—and well-being, implying both physical health and anxiety separation. The latter dimensions showed problems of internal consistency, presumably because of the insufficient number of relevant items. In this respect, further analysis on different aspects of worry is needed in order to give a broader representation of this multifaceted concept. However, parents do not show high levels of worry for the educational context and the child’s social relations, and their concern for the child’s well-being is slightly greater. This suggests that the negative sides of child care experience are perceived to be ordinary aspects to be faced in a developmental context. In addition, parents’ anxieties about the potential harmful impact of service attendance show weak relationships with the values they attribute to this experience, thus indicating that positive and negative aspects of child care pertain to distinct domains.

With reference to parents’ evaluations of the service, seven correlated dimensions were identified, separately concerning the child’s and the parents’ experience. This supports our assumption that parents adopt a twofold approach to the evaluation of child care quality, and clearly distinguish aspects of the service that are capable of satisfying their child’s and their own needs.

The child’s educational experience also plays an important role with regard to evaluations. Parents perceive a special relationship between a child’s achievements (e.g., to stay with others, to do things, to express emotions, etc.) and caregivers’ behaviours (how they care for the child, how they promote their autonomy, how they respect their needs, how they act so that rules are respected and conflict solved). They identify two unrelated dimensions of potential discomfort, referring to their child’s and to their own experience. They attribute their child’s discomfort to their individual difficulties in becoming familiar with the rhythms of the service, its social atmosphere, and the presence of peers, while their own discomfort essentially expresses criticism about caregivers’ social behaviours (both towards the child and themselves) and service organization.

In parents’ evaluations the environment is perceived as a distinct dimension of quality, related to both caregivers’ activities and the child’s educational experience. This finding confirms the strong relationship between child care environment and educational programme found in the evaluations given by experts (Tietze et al. 1998).

The dimension of parents’ participation in the social environment of the service, whose relevance emerged in previous studies (Emlen et al. 1999, 2000; Fantuzzo et al. 2006) includes the relationships with other parents and caregivers, and expresses parents’ demand for socialising and sharing responsibilities in child education and care. In parents’ view, this dimension is related to the context of responsiveness to child and parent emotional needs during first entry, thus confirming that a good social climate in that period also has positive consequences for parents’ relationships with the service (Mantovani 2007; Musatti 2006).

All dimensions of value about child care quality were found to influence parents’ evaluations of the experience made at the service. Although this effect is not equally strong for each dimension, it confirms the relevance of analysing variables at a high-level of abstraction in the study of user views on service quality (Gamble et al. 2009; Lages and Fernandes 2005). The more parents value the different components of service quality (child’s experience, parents’ social relations and parents-caregivers sharing), the better they evaluate the quality of the various aspects of the centre attended (child’s educational experience, the environment, parents’ participation, caregivers’ behaviours, and the context responsiveness). In particular, the importance attributed to child’s experience has a major influence on parents’ evaluations. A positive relationship between values and evaluations of the experience was also found by Cryer et al. (2002), who argued that parents would feel uncomfortable admitting that their child is not adequately cared for in respect of those aspects they value most. We can also hypothesise that a positive experience in the service leads parents to place importance on those aspects that satisfied them. In our study, as in Cryer et al. (2002), high levels of perceived quality were found, and perceived quality may reflect objective quality. Parents might have carefully analysed what they consider to be of highest importance and, because of the actual quality of these aspects, the latter are perceived as valuable.

A different and more complex picture emerged with regard to the relationships between worries and evaluations. Only the evaluation of the child’s discomfort is predicted by all the parent worries. With regard to other dimensions of evaluation, worries were always found to be negative predictors. When parents worry about the quality of the educational context, they make worse evaluations of all aspects of the experience; when parents worry about child’s well-being, this negatively affects the evaluations of aspects concerning the child, while no relationship with the dimensions of quality involving them directly and environment quality emerges; the worry for the child’s social relations shows the weakest predictive power on evaluations.

Parents express high levels of satisfaction with their child care experience, as demonstrated in previous studies (Barnes et al. 2006; Emlen et al. 2000; Peyton et al. 2001). However parents’ satisfaction of their own experience is lower, showing that they make different judgements on the effectiveness of the service when providing answers about their child’s and about their own needs.

The analysis of the relationships among values, evaluations, and overall satisfaction showed that values have a moderate influence on evaluations, and these have the strongest impact on overall satisfaction. The direct influence of values on satisfaction is weak and mainly mediated by the evaluation of the actual experience in the service. A comparison between the models concerning parents’ satisfaction with regard to their child’s and their own experience shows both similarities and differences. Interestingly, child’s discomfort is the only dimension of evaluation which does not influence satisfaction in both models; this supports the idea that parents perceive their child’s difficulties as an unavoidable component of the experience, which is unpleasant in itself but unrelated to overall satisfaction. Although in both models most dimensions of evaluation have a similar predictive power, a relevant difference emerged with regard to the main determinant of satisfaction. Child’s satisfaction is mainly influenced by a child’s educational experience, while parents’ participation in the service is the key-factor leading to parents’ satisfaction.

Family and child characteristics that were found to affect parent’s views in previous research (e.g., Kensinger Rose and Elicker 2008; Kim and Fram 2009) did not emerge as relevant aspects in this study. However, it should be stressed that the context of our study considered infant-toddler centres as the only available child care choice, with defined quality standards and access procedures that led to the selection of families with similar socio-demographic characteristics.

Taken together, our findings show that parents have a multi-faceted view of childcare quality. As Emlen et al. (1999, 2000) argued, ratings of overall satisfaction should not be used as the only measure for assessing service quality, and parents should be solicited in order to consider specific aspects of their experience. Our study confirms the relevance of listening to the parent’s point of view on childcare quality and challenges the hypothesis that parents lack competence, knowledge, and training in evaluating child care quality. Parents emerge as competent evaluators of child care quality, as they express differentiated judgments about the various dimensions of the service. In parents’ views, although issues concerning the child’s education and care play a central role, the relevance of their own needs for social contact with the educators and other parents also emerge.

References

Barnes, J., Leach, P., Sylva, K., Stein, A., Malmberg, L. E., & FCCC Team. (2006). Infant care in England: Mothers, aspirations, experiences, satisfaction and caregiver relationships. Early Development and Care, 176, 553–573.

Bennett, J. (2008). Benchmarks for early childhood services in OECD countries. Innocenti working paper, IWP-2008-02, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence.

Ceglowski, D. (2004). How stake holder groups define quality in child care. Early Childhood Education Journal, 32, 101–111.

Ceglowski, D., & Bacigalupa, C. (2002). Four perspectives on child care quality. Early Childhood Education Journal, 30, 87–92.

Cryer, D., & Burchinal, M. (1997). Parents as child care consumers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 12, 35–58.

Cryer, D., Tietze, W., & Wessels, H. (2002). Parents’ perceptions of their children’s child care: A cross-national comparison. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17, 259–277.

da Silva, L., & Wise, S. (2006). Parent perspectives on childcare quality among a culturally diverse sample. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 31, 6–14.

Davis, E. E., & Connelly, R. (2005). The influence of local price and availability on parents’ choice of child care. Population Research and Policy Review, 24, 301–334.

Early, D. M., & Burchinal, M. R. (2001). Early childhood care: Relations with family characteristics and preferred care characteristics. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 16, 475–497.

Emlen, A. C., Koren, P. E., & Schultze, K. H. (1999). From a parent’s point of view: Measuring the quality of child care. Final report. Portland, OR: Regional Research Institute for Human Services, Portland State University.

Emlen, A. C., Koren, P. E., & Schultze, K. H. (2000). A packet of scales for measuring quality of child care from a parent’s point of view. Portland, OR: Regional Research Institute for Human Services, Portland State University.

European Commission Childcare Network. (1991). Quality in services for young children: A discussion paper. Brussels: European Commission, Equal Opportunities Unit.

European Commission Network on Childcare. (1996). Quality targets in services for young children: Proposals for a ten year action programme. Brussels: European Commission, Equal Opportunities Unit.

Fantuzzo, M., Perry, A., & Childs, S. (2006). Parent satisfaction with educational experiences scale: A multivariate examination of parent satisfaction with early childhood education programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21, 142–152.

Gamble, W. C., Ewing, A. R., & Wilhlem, M. S. (2009). Parental perceptions of characteristics of non-parental child care: Belief dimensions, family and child correlates. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 70–82.

Harms, T., & Clifford, R. (1980). Early childhood environment rating scale. New York: Teachers College Press.

Harms, T., Cryer, D., & Clifford, R. (1990). Infant/toddler environment rating scale. New York: Teachers College Press.

Helburn, S. W., & Howes, C. (1996). Child care cost and quality. The Future of Children, 6, 62–82.

Johansen, A. S., Leibowitz, A., & Waite, L. J. (1996). The importance of child-care characteristics to choice of care. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 759–772.

Katz, L. (1993). Multiple perspectives on the quality of early childhood programs. ERIC document reproduction service no: ED355 041.

Kensinger Rose, K., & Elicker, J. (2008). Parental decision making about child care. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 1161–1184.

Kim, J., & Fram, M. S. (2009). Profiles of choice: Parents’ pattern of priority in child care decision-making. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24, 77–91.

Lages, L. F., & Fernandes, J. C. (2005). The SERVPAL scale: A multi-item instrument for measuring service personal values. Journal of Business Research, 58, 1562–1572.

Larner, M., & Phillips, D. (1994). Defining and valuing quality as a parent. In P. Moss & A. Pence (Eds.), Valuing quality in early child care services: New approaches to defining quality (pp. 43–60). London: Paul Chapman Press.

Leach, P., Barnes, J., Nichols, M., Goldin, J., Stein, A., Sylva, K., et al. (2006). Child care before 6 months of age: A qualitative study of mothers’ decisions and feelings about employment and non-maternal care. Infant and Child Development, 15, 471–502.

Leslie, L. A., Ettenson, R., & Cumsille, P. (2000). Selecting a child care center: What really matters to parents? Child & Youth Care Forum, 29, 299–322.

Mantovani, S. (2007). Pedagogy. In R. S. New & M. Cochran (Eds.), Early childhood education. An international encyclopedia (Vol. 4, pp. 1115–1118). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Murray, M. M., Christensen, K. A., Umbarger, G. T., Rade, K. C., Aldridge, K., & Niemeyer, J. A. (2007). Supporting family choice. Early Childhood Education Journal, 35, 111–117.

Musatti, T. (1993). Quality of child care and children’s quality of life. ERIC document reproduction service no: ED385 342.

Musatti, T. (2006). Children’s and parents needs and early education and care in Italy. In E. Melhuish & K. Petrogiannis (Eds.), Early childhood care and education. International perspectives (pp. 65–76). London & New York: Routledge.

Noble, K. (2007). Parent choice of early childhood education and care services. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 32, 51–57.

OECD. (2001). Starting strong: Early childhood education and care. Paris: OEDC Publishing.

OECD. (2006). Starting strong II: Early childhood education and care. Paris: OEDC Publishing.

Peyton, V., Jacobs, A., O’Brien, M., & Roy, C. (2001). Reasons for choosing child care: Associations with family factors, quality, and satisfaction. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 16, 191–208.

Pungello, E. P., & Kurtz-Costes, B. (1999). Why and how working women choose child care: A review with a focus on infancy. Developmental Review, 19, 31–96.

Pungello, E. P., & Kurtz-Costes, B. (2000). Working women’s selection of care for their infants: A prospective study. Family Relations, 49, 254–255.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). New York: Academic Press.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50, 19–46.

Singer, J. D., Fuller, B., Keiley, M. K., & Wolf, A. (1998). Early child-care selection: Variation by geographic location, maternal characteristics, and family structure. Developmental Psychology, 34, 1129–1144.

Tietze, W., Bairrao, J., Bairreros-Leal, T., & Rossbach, H. (1998). Assessing quality characteristics of center-based early childhood environments in Germany and Portugal. A cross national study. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 13, 283–298.

Zeithaml, V., Parasuraman, A., & Berry, L. (1990). Delivering quality service. Balancing customer perceptions and expectations. New York: The Free Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scopelliti, M., Musatti, T. Parents’ View of Child Care Quality: Values, Evaluations, and Satisfaction. J Child Fam Stud 22, 1025–1038 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9664-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9664-3