Abstract

Pacific peoples represent one of the fastest growing population subgroups in New Zealand and suffer disproportionately from diabetes, obesity, and other diseases. There is little research on the predictors of behavioral problems in Pacific children or the role that cultural variables play in shaping the unique environments in which child development occurs This study aims to examine the: (1) prevalence of behavior problems at 2, 4, and 6 years-of-age among Pacific children, and (2) relationships between maternal, cultural, and socio-demographic factors and behavioral problems. Data were gathered from the Pacific Islands Families Study. Maternal reports of child behavior were obtained using the Child Behavior Checklist for over 1000 Pacific children. The prevalence of clinical internalizing problems at ages 2, 4, and 6 years was 16.8, 22 and 8.5%, and clinical externalizing was 6.7, 10.7, and 14.6% respectively. Significant risk factors associated with clinical internalizing were maternal depression, maternal smoking, intimate partner violence, and having a single mother. Significant risk factors for clinical externalizing were harsh parenting, maternal depression, having a New Zealand born mother, and low household income. Across dimensions, a protective factor was found for children with mothers who described themselves as strongly aligned with Pacific traditions. These findings contribute to the limited longitudinal data specific to children from different ethnic groups and demonstrate the importance of cultural factors in developmental outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pacific peoples living in NZ are an ethnically heterogeneous (predominantly Samoan, 49%; Cook Island Māori, 22%; Tongan, 19%; and Niuean, 9%), rapidly growing, youthful group. Representing 6.9% of the population, they are highly urbanised, with two-thirds living in the Auckland region. Sixty percent of people of Pacific ethnicity were born in New Zealand(NZ), a majority of whom are of Cook Islands, Niuean, or Tokelauan heritage. Of those born overseas, 40% had arrived in NZ by 1981 and 30% between 1981 and 1990 (Statistics New Zealand 2007; Statistics New Zealand & Ministry of Pacific Island Affairs 2010).

Pacific peoples exhibit high levels of social connectedness but significantly poorer social and health outcomes than other ethnic groups in NZ (Statistics New Zealand 2011), including higher rates of morbidity and mortality associated with chronic diseases (Ministry of Health 2004, 2008; Sundborn 2009). Reasons for inequalities in health outcomes are multifarious, intergenerational, and related in a ‘web-of-causation’; i.e., having the greatest burden of interrelated multilevel component risk factors and causes. Numerous factors have been identified that may converge to influence child outcomes in Pacific peoples, including socio economic disparities (Statistics New Zealand 2011), low educational attainment (Ministry of Education 2006), poor housing (Butler et al. 2003; Carter et al. 2005), limited food security (Rush et al. 2007), cultural norms, (Pollock 1995), acculturation (Borrows et al. 2011), family typologies (Fa’alau 2011), and competing health issues (Ministry of Health 2008; Paterson et al. 2006; Sundborn 2009).

The Pacific Islands Families (PIF) study is a longitudinal birth cohort study of 1000 Pacific families which aims to derive an evidence base and holistic understanding of family health and development on which to base appropriate Pacific driven intervention strategies throughout the life course (Paterson et al. 2008). Such longitudinal research is essential to identify and understand the trajectories of health and development in this population of diverse Pacific Island ethnicities.

The mass movement of immigrants to a new land casts children and their families into unfamiliar cultural environments (Crijnen et al. 1997). Acculturation, the process of change that groups and individuals undergo when they come into contact with another culture (Berry 2003), can result in increased levels of anxiety and depression which may lead to a heightened risk of mental health problems for children and their parents (Karlsen and Nazroo 2002). Such acculturation effects were linked with problem behavior among Turkish children living in the Netherlands (Janssen et al. 2004).The mental health of immigrant children is challenging to evaluate due to variations in concepts of psychopathology, how to identify it, and what to do about it. However, behavioral and emotional problems impair so many aspects of child functioning among children that cross cultural methods for identifying such problems are vital for facilitating healthy adaptation to host cultures.

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach and Rescorla 2000) has been used extensively to describe problematic behavior in early childhood in numerous countries (Ivanova et al. 2010; Rescorla et al. 2007, 2011). Researchers, using total problem behavior scores, have found prevalence rates of 11.9% among Turkish children (Erol et al. 2005), 7.9% for Finnish children (Ujas et al. 1999), 7.8% for Dutch children (Koot and Verhulst 1991), between 10 and 18% for German children (Barkman and Schulte-Markwort 2005), and 14.2% for Pacific children (Paterson et al. 2007a). Although there is variability in both instrumentation and definition across research settings, there is agreement that approximately 10–15% of preschool children show mild to moderate problems (Barkman and Schulte-Markwort 2005).

Child behavioral outcomes are influenced, either directly or indirectly, by numerous family factors, including household socioeconomic status, parenting styles and practices, parental physical and mental health and family structure and lifestyles (Chen 2004; Pachter et al. 2006). Ethnicity and cultural orientation are also acknowledged as important contextual family variables to consider when examining problematic child behaviour (Garcia Coll et al. 1996, 2000).

Frequently used markers of socioeconomic status such as parental education (Kahn et al. 2005; Sourander 2001), occupation and family income (Kahn et al. 2005; Santiagao et al. 2011), neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage (Callahan et al. 2011; Schneiders et al. 2003) and minority status (Crijnen et al. 1999) have constantly been associated with problem child behavior. Parenting styles and the home environment have also been shown to have a powerful impact on early child behavior problems. Numerous studies have revealed that punitive types of discipline are associated with problem child behavior (Bordin et al. 2009; Javo et al. 2004; Stormshak et al. 2000). This is highly relevant within Pacific families, with the physical punishment of children being described as customary, common, and widely accepted (Marshall 2005; Pereira 2010). Other family and lifestyle variables associated with problematic child behavior include maternal smoking during pregnancy (Robinson et al. 2008), and current maternal smoking and alcohol consumption (Kahn et al. 2005).

Research has shown the witnessing of domestic violence may have a damaging effect on children’s behaviour (Whitaker et al. 2006). Previous PIF findings revealed a relatively high level of intimate partner violence among Pacific families within the cohort (Paterson et al. 2007b). Maternal depression has also been strongly associated with child behaviour problems (Fleitlich and Goodman 2001). Depressed mothers tend to be more emotionally restrictive and less likely to reward their children thus contributing to the development of behavioural problems (Downey and Coyne 1990).

Studies of minority child outcomes need to be conducted with an appreciation of how differences in contexts affect developmental outcomes. Successful child health and development can be defined as successful adaptation to a specific environment or family context (Pachter et al. 2006). There are no findings reported in the current literature on the role that Pacific cultural variables play in shaping the unique environments in which Pacific children grow and develop. However previous PIF findings showed that retaining strong cultural links is likely to have positive health benefits for Pacific mothers and their children (Borrows et al. 2011).

In order to understand the factors that contribute to child behavioral problems in these diverse ethnic groups we analyzed data from the PIF data set to determine (1) the prevalence of child behavior problems at 2, 4, and 6 years-of-age, and (2) relationships between maternal, cultural, and socio-demographic variables and child behavior.

Method

Participants

The Pacific Islands Families (PIF) study is following a cohort of Pacific infants born at Middlemore Hospital in Auckland between 15 March and 17 December 2000. All potential participants were selected from births where at least one parent identified as being of a Pacific Islands ethnicity and was a New Zealand permanent resident. Participants were identified through the Birthing Unit, in conjunction with the Pacific Islands Cultural Resource Unit, and initial information about the study was provided at the hospital and consent was sought to make a home visit.

The original cohort included 1,376 mothers of 1,398 Pacific infants (including 44 twins) born in Auckland, NZ, during the year 2000. Compared with data available from Statistics New Zealand’s 1996 and 2001 Censuses, the inception cohort was broadly representative of the Pacific census figures. At 24 months, 1,048 (76.2%) mothers were interviewed in relation to 1,064 (76.1%) children. At 4 years, 1,048 (76.1%) mothers were interviewed in relation to 1,066 (76.3%) children. At 6 years, 1,001 (72.7%) mothers were interviewed in relation to 1,019 (72.9%) children. The present study used maternal reports from those participants; this included singletons and one from each pair of twins.

Procedures

At six-weeks, 12 and 24 months, 4 and 6 years postpartum individual interviews were carried out with maternal participants. Female interviewers of a Pacific ethnicity who were fluent in English and a Pacific Islands language visited mothers in their homes. Once informed consent was obtained, mothers participated in 1-h interviews concerning family functioning and the health and development of their child. This interview was conducted in the preferred language (usually English) of the mother, and at the conclusion of the interview the participants were compensated for their time.

The maternal interview was based on measures that were selected from robust standardised tools or were specifically designed for inclusion in the study based on international research and other national and international longitudinal studies. To ensure that the research dimensions were culturally appropriate and salient to end-users, a consultation and focus group process took place with representatives of the Pacific communities, the PIF Pacific Peoples’ Advisory Board and other stakeholders to discuss the cultural appropriateness of our interview protocols. Prior to the commencement of data collection all protocols are piloted with a group of Pacific children and parents to check for conceptual understanding and language. This bi-directional process maximises the opportunity for the PIF Study to reflect the knowledge needs of Pacific peoples and those working with Pacific families. More detailed information about recruitment and procedures is described elsewhere (Paterson et al. 2006).

Measures

Child Behavior

Achenbach and Rescorla (2000) provide preschool and school versions of their CBCL. The 100-item CBCL/1½–5 was used in 24-month and 4-year-old interviews to obtain parental/caregiver ratings of behavioral/emotional problems. The 120-item CBCL/6–18 was used in the 6-year-old interviews. The CBCL is the most commonly used and best-validated behavioural rating scale across many countries and cultures (Rescorla et al. 2007, 2011).

In the preschool checklist, the score for internalizing behavior is the sum of scores for 36 questions within four syndromes: emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, withdrawn, and somatic complaints; and externalizing behavior scores are derived from 24 questions within two syndromes: attention and aggression. In the school-age checklist, the score for internalizing behavior is the sum of scores for 32 questions within three syndromes: anxious/depressed, withdrawn, and somatic complaints; and externalizing behavior scores are derived from 35 questions within two syndromes: aggression and rule breaking.

The CBCL problem behavior scales were normed according to age and gender categories on both clinically referred and non-referred samples of children. In addition, clinical cutoffs on normalized T-scores have been specified for distinguishing referred and non-referred children. For each syndrome, the clinical cutoff corresponded to the 98th percentile (T = 70) with a borderline clinical range defined as the 95–98th percentile (T = 67–70). For the composite scales (Internalizing, Externalizing), the clinical cutoff was set at the 90th percentile (T = 63) and the borderline clinical range was set at the 83rd (T = 60–63).

Extensive psychometric information based on multicultural comparisons is available for the CBCL (Achenbach and Rescorla 2000, Rescorla et al. 2007, 2011). Cronbach’s α values ranged from 0.76 to 0.93 for internalizing, externalizing, and total scores within this cohort. To determine clinically relevant cases we used the Achenbach and Rescorla cut-off values. For all scores, the borderline and clinical ranges were defined as the cut-off points which specify the 83rd and 90th percentiles of a normative sample of non-referred children.

Parenting Practices

The Parent Behavior Checklist (PBC) is a 100-item measure of maternal reported aspects of parenting (Fox 1994) with three subscales: Expectations, Discipline, and Nurturing. To reduce the burden on participants, shortened versions of two subscales were used, namely discipline and nurturing. The former assesses parental responses to children’s challenging behaviors with verbal and corporal punishment; the latter measures specific behavior that promotes a child’s psychological growth. The items for the shortened discipline and nurturance scales were chosen on the basis of high item factor loadings and this resulted in 5 discipline items (e.g. ‘I smack my child’) and 10 nurturing items (e.g. ‘My child and I play together’). This resulted in a modified discipline subscale incorporating original items which correlated more strongly with the ‘discipline’ factor and were, as might be expected, ‘harsher’ in nature. Higher scores in each subscale were indicative of greater nurturance and greater use of discipline practices.

Psychometric properties for the PBC are well established. Alpha and test–retest reliability were high on the original scales with Discipline 0.91, 0.87, and Nurturing 0.82, 0.81 (Fox 1994). In our cohort, the Cronbach’s α was 0.77 for Discipline and 0.71 for Nurturing.

Maternal Mental Health

The 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12: Goldberg and Williams 1988) is a self-report tool that is widely used to identify minor psychiatric disorder in adults. It screens for non-psychotic disorders and focuses on two major areas, the inability to carry out normal functions and the appearance of new and distressing psychological phenomena. (Items include “Have you recently felt you couldn’t overcome your difficulties; Have you recently been able to enjoy your normal day to day activities; Have you recently felt capable about making decisions about things”). High convergent and divergent validity coefficients for the GHQ12 of between 0.83 and 0.93 have been reported in a number of settings (Goldberg et al. 1997; Makowska et al. 2002).The GHQ12 was scored to give a total of 12 using the binary method of scoring. Each item was scored 1 if the answer was “rather more than usual” or “much more than usual”, otherwise it was scored 0. A cut-point of 2 is recommended for screening psychological disorder. Mothers who scored above the cut-point (3 or more) are referred to in this study as symptomatic and mothers who scored below as non-symptomatic. Reliability coefficients of the GHQ in the PIF study were 0.87 (Gao et al. 2007), 0.85 and 0.83, at ages two, four, and six, respectively.

Acculturation

The General Ethnicity Questionnaire (GEQ: Tsai et al. 2000) is based on the concept of acculturation, the process of change that groups and individuals undergo when they come into contact with another culture. Berry (2003) identified four different varieties of acculturation: these are assimilation (replacing Pacific with NZ culture), integration (identification with both), separation (maintaining only Pacific culture) and marginalization (withdrawal from both cultures). For the specific purposes of the PIF study, the scale was shortened and modified thereby developing the Pacific (PIAccult) and New Zealand (NZAccult) versions of the GEQ (Borrows et al. 2011).Tsai et al. (2000) reported good reliability and validity for the GEQ. The internal consistency of the measure was examined using Cronbach’s α, and was found to be acceptable (a = 0.81 and 0.83 for the NZAccult and PIAccult respectively; Borrows et al. 2011).

Severe Intimate Partner Violence

The perpetration of intimate partner violence (IPV) was measured using Form R of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) developed by Straus (1979). The CTS has been used in numerous clinical studies and IPV surveys (e.g. Straus and Gelles 1986). The CTS measure of Severe Physical Violence includes six items. Mothers were identified as perpetrators of severe physical violence if they reported any of the behaviors towards their partner in the past 12 months. Robust psychometric properties of the CTS scales have been described by Straus (1990). The alpha coefficients for the physical aggression subscale are high, ranging from 0.77 to 0.88, in large nationally represented samples (Straus 1990). In the PIF study the Cronbach’s coefficient alpha reliability for severe physical aggression was 0.81.

Postnatal Depression

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS: Cox et al. 1987) was included in the 6-week assessment. The EPDS is a self-report instrument that focuses on cognitive and affective aspects of depression. The scale does not provide a clinical diagnosis of depression, but a score of above 12 is widely used to indicate a probable depressive disorder. The sensitivity specificity and predictive validity of the EPDS has been established in a variety of populations (Berle et al. 2003; Benvenuti et al. 1999). However, the use of the EDPS with Pacific Island mothers is limited (Lealaiuloto and Bridgman 1997). In this study, Pacific interviewers did not report any administration problems, and internal consistency was high overall as well as for specific ethnic groups.

Maternal Lifestyle Factors

Mothers were asked if they smoked during pregnancy, smoked yesterday, were exposed to smoking by others in the home, and if they drank alcohol during pregnancy.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Child gender and ethnicity, maternal age, education level, marital status, household income, and household size were taken into account in this analysis. Socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Following the interviews, dada were coded and double entered into an electronic database (SPSS Data Entry Builder 2.0) that employed comprehensive data validation and checking rules.

Data Analysis

The data were collected from three consecutive waves of the cohort study. A total of 3,093 valid responses were obtained from 1,222 families.

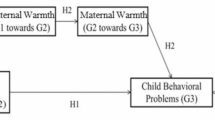

Logistic regression methods were used to investigate the odds of internalizing and externalizing behavior scores in the clinical range. Factors already published as being associated with clinical-range behaviors within this cohort were all considered in the current longitudinal analysis. For this purpose it is useful to distinguish covariates measured only once per subject and those variables measured at each wave. Eight variables were measured at baseline: sex and ethnicity of child, age of mother at child’s birth, mother smoked during pregnancy, mother drank any alcohol during pregnancy, mother was NZ-born, household income category at baseline, and postnatal depression. The two modified maternal-reported discipline and nurturance scores were measured only at the 2 year interview. Eight variables were measured at each wave: mother is partnered or not, acculturation, household size, mother’s highest education level, mother currently smokes, others in household currently smoke, mother shows symptomatic depression, and perpetrator of IPV.

Because of the repeated-measures nature of the data, the statistical analysis made use of generalized estimating equations (GEE: Liang and Zeger 1986) which treats the repeated observations for an individual participant as a cluster and automatically allows for the correlations among them. Correlations among the three waves were assumed to have an ‘unstructured’ pattern, so that the correlation for each of the three pairings was estimated separately from the data.

The analysis of clinical prevalence first looked at these explanatory variables (and their time interaction terms) individually, aiming to identify potential risk and protective factors based on the strength of associations. Some of these were then combined into multivariable models, to allow for confounding, as follows. For each variable, two simple logistic GEE models were created with only that variable and the year variable (one with and one without the time-interaction term) as covariates. This examined the variable’s effect on the odds of a clinical score, and assessed whether this effect varied over time. The year variable (age of the child) was included as a categorical factor in the models. As recommended by Sun et al. (1996) all variables that showed at least a tenuous (p < 0.25) main effect or time interaction effect, and all time interactions similarly tenuous, were selected for inclusion in the multivariable model. Thus a saturated model, including the selected variables and some of their time interactions, formed the starting point of a backwards-stepping variable elimination procedure. The procedure examined multivariable models sequentially, removing the least significant time-interaction term or variable without time-interaction at each step, until only model terms significant at the 5% level remained. Successive models were compared using a Wald test statistic (Højsgaard et al. 2005). This process was performed separately for internalizing and externalizing scores; details of the included variables are presented as results. In line with Sun et al. (1996) and Perneger (1998) no correction has been made for multiple tests.

The PIF Study captures data using SPSS. Data for the present investigation were analysed using R version 2.10.0 with the ‘geepack’ package (Højsgaard et al. 2005).

Results

Descriptives

Prevalence of Problem Behavior

Table 2 presents prevalence rates of clinical range problems. The prevalence of clinical internalizing problems was high at preschool ages (16.8 and 22.0%) but dropped at age six (8.5%). The prevalence of clinical externalizing rose steadily from 6.7% at age two to 14.6% at age six.

Statistical Models

Relationships Between Parenting and Child Behavior

Higher discipline scores were significantly associated with greater odds of clinical externalizing problems (χ2(1) = 25, p < 0.0001) throughout the study, with no significant differences found among the 3 years (χ2(2) = 5.1, p = 0.079). For internalizing, higher discipline scores were significantly associated with greater odds at two (χ2(1) = 9.4, p = 0.002) but not at 4 or 6-years-of-age. However, when this was adjusted for confounding within the multivariable model, the effect was not significant. No significant association was found between nurturance scores and the odds of clinical problems of either type (χ2(1) = 0.61, p = 0.69 for externalizing; χ2(1) = 1.26, p = 0.26 for internalizing).

Relationships Between Socio-Demographic Variables and Child Behavior

For the initial multivariable model of internalizing, terms dropped because of insufficient (p > 0.25) effects were: alcohol during pregnancy (main effect and time-interaction) and mother smokes (time-interaction only). For the externalizing model, no variables were dropped entirely but the following time-interaction terms were dropped: mother’s age at birth, NZ-born, income, smoked during pregnancy, postnatal depression, marital status, mother smokes, others smoke, and household size. All remaining variables and time-interaction terms competed in a backward-stepping elimination procedure until only significant (p < 0.05) terms remained. Results of the final multivariable models are presented as adjusted odds ratios in Tables 3 (internalizing) and 4 (externalizing).

Factors significantly associated with the odds of clinical internalizing (Table 3) were as follows. Higher odds were found for single mothers, mothers who smoke, and mothers with symptomatic depression, with no significant variation of these effects among the 3 years. Acculturation in the separation category appeared to have a lasting protective effect against clinical internalizing, reducing the odds by nearly a third compared to the opposite acculturation, assimilation. At age six, girls showed significantly higher odds than boys (nearly double), whereas no significant gender differences were found at younger ages. Highly significant variations were found by child ethnicity, with few Samoan 2-year-olds and few Tongan 4-year-olds identified as having clinical internalizing problems. Household size had an overall significant time-varying effect, but without any specific significant findings; there is a hint that larger households might increase the odds for 2-year-olds but decrease them for 6-year-olds. Mothers being perpetrators of IPV nearly doubled the odds of clinical internalizing for 4-year-olds and quadrupled them for 6-year-olds, but no significant difference was found among the 2-year-olds.

Factors significantly associated with the odds of clinical externalizing (Table 4) were as follows. The effect of harsh discipline at 2 years on externalizing remained highly significant and showed no abatement through to 6 years. Comparing a discipline score of 1 (the first quartile) to a score of 8 (the third quartile), the model suggests that such an increase of 7 in this score corresponds to 1.6 times greater odds of clinical externalizing. Children born into the lowest income families had significantly greater odds of externalizing problems and this effect was seen to persist throughout. Household size had a weak effect, with children in larger households having slightly greater odds. As with internalizing, acculturation in the separation category was a significant protective factor throughout the 3 years. Girls were significantly more likely than boys to exhibit externalizing at age two, but significantly less likely at age six (no difference at age four). Significant variations were found by child ethnicity, as seen for internalizing. The effect of concurrent maternal depression was an approximately threefold increase in the odds of clinical externalizing among 4-year-olds and 6-year-olds, but with no significant effect for 2-year-olds.

Discussion

Within this Pacific cohort, the prevalence of clinical internalizing problems was high at preschool ages, 16.8% at age two and 22% at age four, but dropped to 8.5% at age six. In contrast, rates of clinical externalizing rose steadily from 6.7% at two, 10.7% at four, and 14.6% at 6-years-of-age. In order to compare with international studies, using the same measure and similar definitions of the clinical range, we examined the prevalence of clinical total scores, which was 14.2% at 2 years, 18.3% at 4 years, and 10% at 6 years. These findings are in line with other studies that used the CBCL in early childhood (Erol et al. 2005; Ujas et al. 1999) which revealed a rate of approximately 10–15% of preschool children exhibiting mild to moderate problems (Barkman and Schulte-Markwort 2005).

It has been posited that pressures of migration may lead to problematic child behavior (Berry 2003). The acculturative stress that is likely to occur in immigrant families impacts on parents and children in many ways. Discipline and parenting skills often need to change in the new country and thus parents with few parenting skills tend to feel that control of their children has been undermined. The changes in family life due to circumstances such as long working hours or distances to travel to work are likely to impact on parent–child relationships (Thomas 1995). We found that retention of traditional Pacific culture and minimal ties with the wider NZ society (defined as separation) serve a protective role for both clinical internalizing and externalizing behavior across early childhood. The retention of Pacific traditions may protect the mother against acculturative stress (Berry 1990) thus mitigating the detrimental effects on child outcomes. This protective factor is likely to be due to the support that the retention of strong social connectedness and close extended family ties brings to parents of young children. Traditional gatherings that take place in Pacific life are characterised by elaborate involvement of people in groups and relevant rituals and ceremonies that support mothers and children across early childhood years (Mulitalo-Lauta 2000). The important part that such traditions play in family life is highlighted by the finding that NZ-born mothers reported significantly more clinical externalizing behavior in their children than Pacific Island-born mothers. This may be due to the longer time they have spent away from their Island roots and the resultant breakdown of ties with Pacific traditions over time and the support systems that such ties bring.

Significant variations over time were found by child ethnicity, with few Samoan 2-year-olds and few Tongan 4-year-olds identified as having clinical internalizing problems. These findings may be explained by normative cultural values that exist within the different ethnic groups and processes that result from social stratification mechanisms. As such they demonstrate the powerful role that variables such as ethnicity play in shaping the development of children (Garcia Coll et al. 1996, 2000; Pachter et al. 2006). Ethnic differences may be partly explained by immigration patterns. In general, the Samoan population is well established in New Zealand and is substantially larger than all other Pacific ethnic groups. It is possible that having strong and numerous bonds to identify with may have a protective influence in terms of health and developmental outcomes for children and families (Statistics New Zealand 2007). These findings provide support for the view that retaining and enhancing strong cultural ties for Pacific immigrants is likely to have positive outcomes. However such cultural values and the way they affect child development are difficult to understand without further in depth qualitative investigation.

Harsh parenting styles and disrupted home environments have been linked to early child behavior problems in a number of different cultures (Gershoff 2002). In line with international studies (Bordin et al. 2009), we found that harsh parenting of 2-year-olds had a lasting effect, significantly increasing the odds of the child exhibiting clinical externalizing behavior through to 6 years of age. Within a Pacific context, it is reported that parents view physical punishment as acceptable (Pereira 2010; Marshall 2005), and harsh discipline as necessary because problem behavior can bring shame on the family (Fairbairn-Dunlop 2001). Within this cohort, we also found that the odds of children exhibiting clinical behavior, both externalizing and internalizing, were more than doubled for those with mothers reporting symptomatic depression. This finding is disturbing because depression is a disabling disorder that is often recurrent (Belsher and Costello 1988). Thus children who are impacted by maternal depression may experience repeated instances of maternal depression and the distress that it brings (Malcarne et al. 2000). These Pacific mothers and children represent important targets for preventative interventions.

The damaging effects on children of witnessing partner violence have been well described (Wolfe et al. 2003; Whitaker et al. 2006). We found that mothers who were perpetrators of severe IPV increased the risk of internalizing in children at ages 4 and 6 years. Other studies have shown that, during the preschool years, children who have witnessed parental conflict exhibit high levels of anxiety and fearfulness (Wolfe et al. 2003). Moreover marital conflict has been shown to negatively affect family functioning and parenting (Cox et al. 2001).

The effects of economic deprivation on child development remain of concern in Western developed countries (Callahan et al. 2011). We found that mothers who were in the lowest income band nearly doubled the odds of clinical externalizing in their children. In addition, being a single parent significantly increased the odds of clinical internalizing. Child poverty varies markedly by family structure with children in single-mother families exhibiting poorer outcomes on most health and wellbeing indicators than children living with two biological parents (Bramlett and Blumberg 2007). The absence of a parent means less supervision, support, and reduced economic resources in the home which can undermine parental wellbeing and parenting effectiveness (Dunn et al. 2004). Linked to this are lifestyle factors, including current maternal smoking which has been consistently linked with high levels of problematic child behavior (Kahn et al. 2005). In this cohort, current maternal smoking increased the odds of clinical internalizing in children. However, maternal smoking or drinking during pregnancy had no effect at the ages measured, and no significant associations were found with other socio-demographic variables. These multiple features of children’s environment, the quality of parenting styles and behaviors and the economic stress that prevails in the family and neighborhood (Schneiders et al. 2003) exert a powerful influence on the development of children and on many aspects of children’s behavior. These findings illustrate the strong influence of the home environment and the impact of multiple factors overtime on child outcomes.

It is important to recognize that this analysis is constrained by the nature of large longitudinal studies, with multidisciplinary questionnaires resulting in lesser opportunity to drill down into multifaceted issues. This limits the degree to which the specific role of Pacific subcultures and their elements can be elucidated. In terms of the CBCL, we used the recommended cut-off criteria (Achenbach and Rescorla 2000) to define the presence of problem behavior. Although these data are based on maternal report we are confident that the multicultural robustness of the CBCL (Rescorla et al. 2011) measured specific problem behavior across the Pacific ethnic groups with reasonable accuracy.

A significant strength of the PIF study is the strong representation of Pacific researchers and maternal interviewers on the team that heightens the cultural sensitivity of our methods and procedures. Cultural appropriateness of the study is strengthened by the independent Pacific People’s Advisory Board, composed of senior Pacific community representatives, established to guide the PIF management team in the scientific and cultural directions of the research. The findings are based on a robust birth cohort with the island-specific distributions being approximately representative of the ethnic distribution of the Pacific population in New Zealand.

These findings are of importance to policy makers in New Zealand who strive to respect the different languages and cultures of the different Pacific groups rather that view them as a single Pacific ethnicity. Information about the risk factors underlying child behavior problems is an essential component of sound public policy. Maternal depression and child behavior problems are both treatable conditions and their interconnections can be used to enhance prevention and treatment efforts. Likewise, modification of harsh parenting practices is a constructive tool for successful intervention. The protective role of maternal alignment with Pacific traditions and the powerful, though inconsistent, association between child ethnicity and behavior demonstrates the importance of cultural factors in developmental outcomes and thus in policy planning.

This unique study of Pacific families will contribute to the limited longitudinal data specific to early childhood from different ethnic groups, highlighting the importance of cultural factors in developmental outcomes, and will provide Pacific agencies with empirical information to utilize in the planning of child and family services.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Barkman, C., & Schulte-Markwort, M. (2005). Emotional and behavioral problems of children and adolescents in Germany. Society of Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(5), 357–366.

Belsher, G., & Costello, G. C. (1988). Relapse after recovery from unipolar depression: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin, 104(1), 84–96.

Benvenuti, P., Ferrara, M., Niccolai, C., Valoriani, V., & Cox, J. L. (1999). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Validation for an Italian sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 53(2), 137–141.

Berle, J., Aarre, T., Mykletun, A., Dahl, A., & Holston, F. (2003). Screening for postnatal depression: Validation of the Norwegian version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, and assessment of risk factors for postnatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 76(1–3), 151–156.

Berry, J. W. (1990). Psychology of acculturation. In J. J. Berman (Ed.), Cross-cultural perspectives: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1989 (Vol. 37, pp. 201–234). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. B. Organista, & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement and applied research (pp. 17–37). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bordin, I. A., Duarte, C. S., Peres, C. A., Nascimento, R., Curto, B. M., & Paula, C. S. (2009). Severe physical punishment: Risk of mental health problems for poor urban children in Brazil. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 87(5), 336–344.

Borrows, J., Williams, M., Schluter, P., Paterson, J., & Helu, S. L. (2011). Pacific Islands Families Study: The association of infant health risk indicators and acculturation of Pacific Island mothers living in New Zealand. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(5), 699–724.

Bramlett, M. D., & Blumberg, S. J. (2007). Family structure and children’s physical and mental health. Health Affairs, 26(2), 549–558.

Butler, S., Williams, M., Tukuitonga, C., & Paterson, J. (2003). Problems with damp and cold housing among Pacific families in New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal, 116(1177), 1–8.

Callahan, K. L., Scaramella, L., Laird, R., & Sohr-Preston, S. (2011). Neighborhood disadvantage as a moderator of the association between harsh parenting and toddler-aged children’s internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 68–76.

Carter, S., Paterson, J., & Williams, M. (2005). Housing tenure: Pacific families in New Zealand. Urban Policy and Research, 23(4), 413–428.

Chen, E. (2004). Why socioeconomic status affects the health of children: A psychosocial perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science: A Journal of the American Psychosocial Society, 13(3), 112–115.

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 782–786.

Cox, M. J., Paley, B., & Harter, K. (2001). Interpersonal conflict and parent-child relationships. In J. Grych & F. Findam (Eds.), Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and application (pp. 249–272). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crijnen, A. A., Achenbach, T. M., & Verhulst, F. C. (1997). Comparisons of problems reported by parents of children in 12 cultures: Total problems, externalising, and internalising. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(9), 1269–1277.

Crijnen, A. A., Achenbach, T. M., & Verhulst, F. C. (1999). Problems reported by parents of children in multiple cultures: The Child Behavior Checklist syndrome constructs. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(4), 569–574.

Downey, G., & Coyne, J. (1990). Children of depressed parents: An integrative view. Psychological Bulletin, 108(1), 50–76.

Dunn, J., Cheng, H., O'Connor, T. G., & Bridges, L. (2004). Children's perspectives on their relationships with non-resident fathers: Influences, outcomes, and implications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 555–566

Erol, N., Sinsek, Z., Oner, O., & Munir, K. (2005). Behavioral and emotional problems among Turkish children at ages 2 and 3 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(1), 80–87.

Fa’alau, F. (2011). Organisation and dynamics of family relations and implications for the wellbeing of Samoan yYouth in Aotearoa, New Zealand (Unpublished PhD thesis), Massey University, New Zealand.

Fairbairn-Dunlop, P. (2001). Tetee Atu: To hit or not to hit. Journal of Pacific Studies, 25(1), 203–229.

Fleitlich, B., & Goodman, L. (2001). Social factors associated with child mental health problems in Brazil: Cross sectional survey. British Medical Journal, 323(7313), 599–600.

Fox, R. A. (1994). Parent behavior checklist. Brandon, VT: Clinical Psychology Publishing Co.

Gao, W., Paterson, J., Abbott, M., Carter, S., & Iusitini, L. (2007). Maternal mental health and child behavior problems at 2 years: Findings from the Pacific Islands Families Study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 41(11), 885–895.

Garcia Coll, C., Akerman, A., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). Cultural influences on developmental processes and outcomes. Implications for the development of psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 12(3), 333–356.

Garcia Coll, C., Lamberty, G., Jenkins, R., McAdoo, H. P., Crnic, K., & Wasik, B. H. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914.

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behavior and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539–579.

Goldberg, D., Gater, R., Sartorius, N., Ustun, T. B., Piccinelli, M., Gureje, O., et al. (1997). The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 191–197.

Goldberg, D., & Williams, P. (1988). A user’s guide to the GHQ. Windsor: NFER-Nelson.

Højsgaard, S., Halekoh, U., & Yan, J. (2005). The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. Journal of Statistical Software, 15(2), 1–11.

Ivanova, M. Y., Achenbach, T. M., Rescorla, L. A., Harder, V. S., Ang, R. P., Bilenberg, N., …, Verhulst, F. C. (2010). Preschool psychopathology reported by parents in 23 societies: Testing the seven-syndrome model of the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1.5–.5. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(12), 1215–1224.

Janssen, M. M. M., Verhulst, F. C., Bengi-Arlsan, I., Erol, N., Salter, C. J., & Crijnen, A. A. M. (2004). Comparison of self- reported emotional and behavioral problems in Turkish immigrant, Dutch and Turkish adolescents. Society of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(2), 133–140.

Javo, C., Ronning, J., Heyerdahl, S., & Rudmin, F. W. (2004). Parenting correlates of child behavior problems in a multi ethnic community sample of preschool children in northern Norway. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 13(1), 8–18.

Kahn, R. S., Wilson, K., & Wise, P. (2005). Intergenerational health disparities: Socioeconomic status, women’s health conditions, and child behavior problems. Public Health Reports, 120(4), 399–408.

Karlsen, S., & Nazroo, J. Y. (2002). Relation between racial discrimination, social class and health among ethnic minority groups. American Journal of Public Health, 92(4), 624–631.

Koot, H. M., & Verhulst, F. C. (1991). Prevalence of problem behavior in Dutch children aged 2–3. Acta Psychiatra Scandinavia, 83(s367), 1–37.

Liang, K. Y., & Zeger, S. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73(1), 13–22.

Lealaiauloto, R., & Bridgman, G. (1997). Pacific Island postnatal distress. Auckland, Mental Health Foundation of Aotearoa/New Zealand

Makowska, Z., Merecz, D., Moscicka, A., & Kolasa, W. (2002). The validity of the General Health Questionnaires, GHQ-12 and GHQ-28, in mental health studies of working people. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 15(4), 353–362.

Malcarne, V. L., Hamilton, N. A., Ingram, R. E., & Taylor, L. (2000). Correlates of distress in children at risk for affective disorder: Exploring predictors in the offspring of depressed and nondepressed mothers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 59(3), 243–251.

Marshall, K. (2005). Cultural issues. In A. B. Smith, M. M. Gollop, N. J. Taylor, & K. A. Marshall (Eds.), The discipline and guidance of children: Messages from research (pp. 53–78). Wellington: Office of the Children’s Commissioner.

Ministry of Education. (2006). Educate: Ministry of Education Statement of Intent 2006–2011. Wellington: Author.

Ministry of Health. (2008). Pacific Child Health: A paper for the Pacific Health & Disability Action Plan Review. Wellington: Author.

Ministry of Health, & Ministry of Pacific Island Affairs. (2004). Tupu Ola Moui: The Pacific Health Chart Book 2004. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Mulitalo-Lauta, P. T. (2000). Fa’asamoa and social work within the New Zealand context. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press Ltd.

Pachter, L. M., Auinger, P., Palmer, R., & Weitzman, M. (2006). Do parenting and the home environment, maternal depression and chronic poverty affect child behavioral problems in different racial-ethnic groups. Pediatrics, 117(4), 1329–1338.

Paterson, J., Carter, S., Gao, W., & Perese, L. (2007a). Pacific Islands Families Study: Behavioral problems among two-year-old Pacific children living in New Zealand. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(5), 514–522.

Paterson, J., Carter, S., Tukuitonga, C., & Williams, M. (2006). Health problems among six-week-old Pacific infants living in New Zealand. Medical Science Monitor, 12(2), CR51–CR54.

Paterson, J., Feehan, M., Butler, S., Williams, M., Cowley-Malcolm, E. T., & Karsten, H. (2007b). Intimate Partner Violence within a cohort of Pacific mothers living in New Zealand. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(6), 698–721.

Paterson, J., Percival, T., Schluter, P., Sundborn, G., Abbott, M., Carter, S., …, Rush, E. (2008). Cohort profile: Pacific Islands Families (PIF) Study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 37(2), 273–279. doi:10.1093/ije/dym171.

Pereira, J. (2010). Spare the rod and spoil the child: Samoan perspectives on responsible parenting. Kotuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 5(2), 98–109.

Perneger, T. V. (1998). What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. British Medical Journal, 316(7139), 1236–1238.

Pollock, N. J. (1995). Cultural elaborations of obesity-fattening practices in Pacific societies. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 4(4), 357–360.

Rescorla, L., Achenbach, T., Ivanova, M. Y., Dumenci, L., Almqvist, F., Bilenberg, N., et al. (2007). Behavioral and emotional problems reported by parents of children ages 6 to 16 in 31 societies. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 15(3), 130–142.

Rescorla, L. A., Achenbach, T. M., Ivanova, M. Y., Harder, V. S., Otten, L., Bilenberg, N., et al. (2011). International comparisons of behavioral and emotional problems in preschool children: Parents’ reports from 24 societies. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40(3), 456–467.

Robinson, M., Oddy, W. H., Li, J., Kendall, G. E., de Klerk, N. H., Silburn, S. R., et al. (2008). Pre- and postnatal influences on preschool mental health: A large-scale cohort study. The Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 49(10), 1118–1128.

Rush, E., Puniani, N., Snowling, N., & Paterson, J. (2007). Food security, selection, and healthy eating in a Pacific Community in Auckland, New Zealand. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 16(3), 448–454.

Santiagao, C. D., Wadsworth, M. E., & Stump, J. (2011). Socioeconomic status, neighbourhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(2), 218–230.

Schneiders, J., Drukker, M., van der Ende, J., Verhulst, F. C., van Os, J., & Nicolson, N. A. (2003). Neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage and behavioral problems from late childhood into early adolescence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57(9), 699–703.

Sourander, A. (2001). Emotional and behavioural problems in a sample of Finnish three-year-olds. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 10(2), 98–104.

Statistics New Zealand. (2007). Pacific profiles: 2006. Retrieved 26 April, 2010, from http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/about-2006-census/pacific-profiles-2006.aspx.

Statistics New Zealand. (2011). Demographic trends: 2010. Wellington: Author.

Statistics New Zealand & Ministry of Pacific Island Affairs. (2010). Demographics of New Zealand’s Pacific population. Wellington: Author.

Stormshak, E. A., Bierman, K. L., McMahon, R. J., & Lengua, L. J. (2000). Parenting practices and child disruptive behavior problems in early elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(1), 17–29.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence. The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41(1), 75–88.

Straus, M. A. (1990). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. In M. A. S. R. J. Gelles (Ed.), Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families (pp. 29–47). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Straus, M. A., & Gelles, R. J. (1986). Societal change and change in family violence from 1975 to 1985 as revealed by two national surveys. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 48(3), 465–479.

Sun, G.-W., Shook, T. L., & Kay, G. L. (1996). Inappropriate use of bivariable analysis to screen risk factors for use in multivariable analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 49(8), 907–916.

Sundborn, G. (2009). Cardiovascular disease risk factors and diabetes in Pacific adults: The Diabetes Heart and Health Study (DHAH), Auckland, New Zealand 2002/03 (Unpublished PhD thesis). University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Thomas, T. N. (1995). Acculturative stress in the adjustment of immigrant families. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 4(2), 131–142.

Tsai, J. L., Ying, Y., & Lee, P. A. (2000). The meaning of “Being Chinese” and “Being American”: Variation among Chinese American young adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(3), 302–332.

Ujas, H., Rautava, P., Helenius, H., & Sillanpaa, M. (1999). Behaviour of Finnish 3-year-old children. I: Effects of sociodemographic factors, mother’s health and pregnancy outcomes. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 41(6), 412–419.

Whitaker, R. C., Orzol, S. M., & Kahn, R. S. (2006). Maternal mental health, substance abuse, and domestic violence in the year after delivery and subsequent behavior problems in children at age 3 years. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(5), 551–560.

Wolfe, D. A., Crooks, C. V., Lee, V., McIntyre-Smith, A., & Jaffe, P. G. (2003). The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(3), 171–187.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paterson, J., Taylor, S., Schluter, P. et al. Pacific Islands Families (PIF) Study: Behavioural Problems During Childhood. J Child Fam Stud 22, 231–243 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9572-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9572-6