Abstract

Interpersonal touch has been little studied empirically as an indicator of parent- and peer-child intimacy. Undergraduate students (n = 390) were studied using a questionnaire survey regarding the frequencies of interpersonal touch by father, mother, same-sex peers, and opposite-sex peers during preschool ages, grades 1–3, grades 4–6, and grades 7–9, as well as their current attachment style to a romantic partner and current depression. A path model indicated that current depression was influenced significantly by poorer self- and other-images as well as by fewer parental interpersonal touches throughout childhood. Other-image was influenced by early (up to grade 3) parental interpersonal touch. Our findings suggest that a lower frequency of parental touching during childhood influences the development of depression and contributes to a poorer image of an individual’s romantic partner during later adolescence and early adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The concept of attachment has been attracting the interest of both clinicians and researchers in family studies. Bowlby’s (1973) theory of attachment explains the nature of a child’s ties to his or her parents in regards to biological function. This accounts for the unstable behavioural responses observed in infants who are separated from figures to whom they are significantly attached, such as the mother. Attachment to the mother will eventually be imprinted and remain throughout life and work as the ‘standard’ mode in which adolescents and adults relate to their significant others, including romantic partners and spouses (Bowlby 1973, 1988). In addition to the development of measures that assess children’s attachment, the last couple of decades have seen the development of measures of adult attachment styles (Collins and Read 1990; George et al. 1985; Hazan and Shaver 1987; Main et al. 1985).

Bartholomew (1990) and Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) defined four prototypic attachment patterns using combinations of a person’s self-image (positive or negative) and image of others (positive or negative), and developed a four-item scale, the Relationship Questionnaire (Bartholomew and Horowitz 1991). In Bartholomew’s (1990) formulation, the “self” model refers to the degree to which a person has internalized a sense of his or her self-worth. Lack of such a capacity results in anxiety and dependence on another person’s approval in close relationships. Low self-worth is characterised by feelings of anxiety and uncertainty with regards to the self’s lovability. The “other” model refers to the degree to which others are generally expected to be available and supportive. Presence or absence of such a capacity results in the seeking out or avoidance of closeness in relationships, respectively.

The four adult attachment types are based on the combination of the “self” and “other” models. Secure people are characterized by a positive self-image and hold positive images of others. Possessing high autonomy and capable of intimacy, they can use other sources of support when needed. Preoccupied people are characterized by a negative self-image and hold positive images of others. Their focus is on the gratification of their needs, and thus they actively seek to have these needs fulfilled in their close relationships. They become excessively dependent on others. Fearful people have a negative self-image and hold negative images of others. Though needing attachment figures, they generally avoid becoming close because they fear or expect that they will be rejected. Finally, dismissing people have a positive self-image and hold negative images of others. They can maintain their positive self-image by distancing themselves from those who are sources of attachment.

Characteristics of parent–child relationships may determine adult attachment styles. For example, adult attachment patterns of Japanese university students are linked to parental care and low overprotection (Liu et al. 2008; Matsuoka et al. 2006 Tanaka et al. 2008). Children’s insecure attachment styles are linked to their maltreatment experiences (for review, Baer and Maritez 2006). Children aged 6–12 who had been physically abused or neglected were more likely to be categorised as insecure in their attachment styles than those who had never been abused (Finzi et al. 2000). In adult patients with borderline personality disorder, insecure attachment styles are associated with childhood abuse history (Minzenberg et al. 2006).

Interpersonal touch is a form of love and affection in the context of the family and other environments. Clinical research on interpersonal touch was initiated with the study of institutionalized infants (Spitz 1945). Spitz (1945) noticed a high mortality rate in infants who received only brief or no touch from nurses. He posited that food and sanitary conditions alone were insufficient for survival, and that interpersonal touch should be regarded as a biological necessity, not just a sentimental or romantic desire (e.g., Korner and Grobstein 1966). Subsequently, Harlow’s (1958) animal study on maternal deprivation and physical contact provided the first scientific evidence regarding the role of interpersonal touch in social and emotional development and confirmed that the need for physical contact is of the same importance as the need for food. The word “touch” may be defined as putting hands on someone in order to show them kindness or affection. It is generally believed that touch is not just an action, but the form of nonverbal communication within an interpersonal relationship that can best promote physical and psychological intimacy, especially between parents and their children. Clinically, the emotional arousal and calming effects of physical contact with patients is important in nursing (Richmond et al. 1987). Simply placing a hand on a loved one who is sick comforts the sufferer.

Some research has noted that interpersonal touch plays a critical role in the maintenance of close relationships between parents and children and consequently shapes the child’s emotional balance, psychological well-being, and the capacity to lead a normal and healthy adult life (Andersen and Leibowitz 1978; Burgoon et al. 1984; Guerrero and Andersen 1991; Johnson and Edwards 1991; Pisano et al. 1986; Willis and Briggs 1992). The 1980s witnessed a renewed recognition of the importance of interpersonal touch, and a number of studies on infant development demonstrated that early interpersonal touch by caregivers had a positive effect on both physical and psychological well-being in the early years of life (Montagu 1986). Field et al. (1986) and Field (1995) found that newborn infants weighed more and achieved superior performance on developmental assessments as a result of a touch program, and that children exposed to increased interpersonal touch experienced a significant decrease in depression, anxiety, and stress levels. Other studies have emphasized a correlation between interpersonal touch and enhanced child development in the early years of life. In an observational study of infants and their mothers, conducted between the end of the infant’s first month and the end of their first year, infants frequently touched by their mothers were comparatively more cooperative and independent and less anxious and rejecting than those whose mothers were inconsistent in their tactile support (Ainsworth 1979; Bell and Ainsworth 1972). The experience of early touch has also been found to be associated with personality later in life, in areas such as self-esteem, social competence, and satisfaction with life (Deethardt and Hines 1983; Fromme et al. 1989; Jones and Brown 1996).

Attachment theory provides an ideal framework for understanding the developmental importance of physical contact, not only in the beginning years of life, but throughout the adolescent and adult years (Banmen 1986). Echoing Spitz and Hawlow’s view mentioned above, Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980) proposed that touch is the most fundamental means by which caregivers express love for their infants, and that physical contact with an attachment figure serves as the infant’s tangible indication of safety. The initial touch between mother and infant creates a desire for further physical contact with the mother in later years, and this physical contact then leads to emotional contact. As such, being touched by the attachment figure is an ultimate signal of “proximity seeking and maintenance”, a basic concept in attachment theory. Consistent with this interpretation, a host of observational studies have demonstrated that physical contact greatly affects later attachment between mother and infant and have identified close physical contact as an antecedent to attachment security (Ainsworth et al. 1978; Anisfeld et al. 1990; Egeland and Farber 1984; Grossman et al. 1985; Sroufe et al. 1993).

Taking into consideration the significance of interpersonal touch by parents and peers, we speculate that the frequency of interpersonal touch during childhood underlies psychological adjustment and adult attachment styles in early adulthood, because adult attachment is associated with different types of psychopathology (Armsden and Greenberg 1987; Belsky and Cassidy 1994; Marcus and Betzer 1996). In this study we pay attention to depression because it is prevalent in adolescence and early adulthood (Astin 1993).

Several studies have shown that insecure attachment may be linked to depression (Armsden et al. 1990; Beatson and Taryan 2003; Bifulco et al. 2002; Rosenfarb et al. 1994). This association was reported in longitudinal studies (Kenny et al. 1998; Liu et al. 2009). Therefore, interpersonal touch during childhood may be associated with depression in early adulthood either directly or through mediation by adult attachment styles.

In current Japanese society, although physical contact such as interpersonal touch and hugging have been attracting considerable attention in the media and are commonly acknowledged as important in infant and child development, very few studies on interpersonal touch have been published in research journals. In addition, although prior research has demonstrated that physical contact is associated with psychological well-being and attachment styles, very little is known about the way in which it influences these two factors. Therefore, according to Bowlby’s attachment theory, we divided attachment into self-image and other-image with the goal of ascertaining the relationship among physical contact, depression, and attachment. We report here a preliminary study on the effects of parental and peer touch during childhood on attachment to a romantic partner as well as on depression among college students in Japan.

Methods

Participants

Students of two universities and one college were solicited to participate in the questionnaire survey. A total of 691 students responded, consisting of 106 men and 478 women. The gender was not reported by 107 students. Their ages were between 18 and 46 years old, with a mean (SD) age of 20.2 (2.9) for men and 18.8 (0.9) for women. Women were significantly (t = 4.9, p < 0.001) younger than men. Because we were interested in the effects of interpersonal touch during childhood on psychological adjustment in young adults, we excluded students aged 26 or over.

Of the participants, 63 students reported the loss of their father for longer than one year before age 16, while the same was true for seven students with regards to their mother. Five students reported the loss of their father by death before the age of 16 (none reported such a loss of their mother). These students were excluded from further analyses because they lacked significant parental experiences, the focus of our study. This resulted in 390 students. The mean (SD) age of men and women was 19.9 (1.2) and 18.8 (0.8) years old, respectively. Men were significantly older than women (t = 7.4, p < 0.001).

Measurements

Interpersonal Touch Experiences

We asked the participant about how often he or she was touched by (1) father, (2) mother, (3) same-sex peers, and (4) opposite-sex peers during (1) their preschool years, (2) grades 1 to 3, (3) grades 4–6, and (4) grades 7–9. Each response was recorded on a 10-point scale from never—0 to very frequently—9.

Adult Attachment Style

We used the Adult Attachment Relationship Questionnaire (RQ: Bartholomew and Horowitz 1991). This is a brief self-measure of adult attachment to a romantic partner. It is composed of four paragraphs, describing each attachment style: Secure, Fearful, Preoccupied, and Dismissing. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which each description would correspond to their relationship with their partner. If they had no definite partner, they were requested to imagine a close opposite-sex person in answering the question. Each item was rated on a 7-point scale ranging from “Does not apply to me at all” to “Applies to me very much”. Its reliability (Bartholomew and Horowitz 1991) and validity (Griffin and Bartholomew 1994) have been reported. With the permission of Dr. Bartholomew, the RQ was translated into Japanese (T. K.). In accordance with Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) we created composite variables of the self-image and other-image, as delineated in the following formulae:

Depression

We used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D: Radloff 1977). The CES-D is a 20-item self-report for screening depression. Each item was reported on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (“never or rarely”) to 3 (“always”). Mean values were substituted for missing data only when at least eight items of the CES-D were answered.

Statistical Analysis

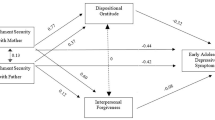

First, we performed an exploratory factor analysis of the Interpersonal touch Experiences. After obtaining factor scores, means and SDs of all the variables used in this study were calculated, as were correlations between them. We then created a structural equation model and hypothesized the following (Fig. 1):

-

1.

The factor scores of the Interpersonal touch experiences would influence the self- and other-images and depression.

-

2.

The self- and other-images would influence depression

X2/df, goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used as goodness-of-fit indices. According to conventional criteria, X2/df < 3, GFI > 0.90, AGFI > 0.85, CFI > 0.95, and RMSEA < 0.08 indicate an acceptable fit and X2/df < 2, GFI > 0.95, AGFI > 0.90, CFI > 0.97, and RMSEA < 0.05 indicate an good fit (Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003). In order to improve the model’s fit with the data, modification indices were used and new covariance estimates were consecutively added. We paid most attention to the point that the modification suggested by modification indices should make theoretical or common sense (Arbuckle and Wothke 1955, p. 153).

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 16.0 and Amos 6.0.

Results

Factor Structure of Childhood Touch Experiences

Exploratory factor analysis yielded three factors (Table 1). Experiences of being touched by same-sex and opposite-sex peers were loaded highly in the first factor, and we therefore named this factor “Peer Touch”. Paternal and maternal touch experiences during grades 4–9 were loaded highly in the second factor; we named this factor “Later Parental Touch”. Finally, touch experiences by fathers and mothers before grade 4 were loaded highly in the third factor, which we termed “Early Parental Touch”. We calculated factor scores for each of these.

We then calculated correlations between all the variables used for this study and the scores of the three touch experience factors (Table 2). Three types of touch experience were significantly correlated with each other. Both Later and Parental Touch scores were inversely correlated with CESD scores but only Early Parental Touch scores were correlated with other-image score. CESD scores were inversely correlated with self-image scores.

Path Analysis

In order to perform SEM, we deleted cases with missing data casewise, which resulted in 342 cases. The original path model failed to show a good fit with the data: X 2/df = 31.9, GFI = 0.882, AGFI = 0.382, CFI = 0.882, and RMSEA = 0.301. Modification indices suggested covariances between the three types of touch experiences. The revised path model showed extremely good fit (Fig. 2): X 2/df = 0.001, GFI = 1.000, AGFI = 1.000, CFI = 1.000 and RMSEA = 0.000. In this model, Depression was influenced significantly by poorer self-image as well as by fewer Early Parental Touch experiences throughout childhood. other-image was influenced by Early Parental Touch.

Discussion

An exploratory factor analysis indicated that experiences of being touched by parents and peers consisted of three components. Touch by same- and opposite-sex peers over the whole span of childhood can be seen as a single concept. Touch by parents, however, may have different effects depending on whether the child is older or younger than age eight. Touch by the father and mother may be more strongly perceived by a younger child as a reflection of an affectionate bond. Parental touch may give a child a sense of warmth, security and protection, and parents may be viewed as reliable and trustworthy. This echoes the present finding that Early Parental Touch induced a positive other-image. According to attachment theory, the origin of adult attachment dates back to the earliest days of life. Similarly, object relations theory dictates that the good object (in the outer world) is introjected into the psyche as the good internal object that will in turn determine the subsequent psychological relationship with the external world. Blatt (1974), who integrated psychoanalytic theory and cognitive psychology, suggested that representations of self and others develop epigenetically becoming gradually more accurate, articulated, and complex. Adult attachment styles may be the end product of the psychosocial influences on a person over the course of their development. The present study suggests that parental bodily touch has a stronger influence on the development of a secure other-image when it is provided to children earlier rather than later.

Interpersonal touch may be associated with perceived personal space. Personal space is the psychological distance between two or more individuals. It can be measured directly using the Stop-Distance Method (SDM; Barnard and Bell 1982) or with a projective measure such as the Felt Figure Technique (FFT; Kueth 1962a, b), and Pedersen Personal Space Measure (PPSM; Pedersen 1973). Clinicians recognise that the physical distance between a young client and his or her parents becomes shorter as a result of family therapy. Parental bodily touch during childhood may reduce the perceived distance between a child and other people, the significant other in particular, so that the child can develop and maintain a secure image of others.

As mentioned in the Introduction, prior research has suggested that early physical contact is associated with the attachment of children to their mothers. Our study extends this association into adult attachment. However, when we divided adult attachment into self- and other-image according to attachment theory and tried to further clarify the relationship between touch and attachment, contrary to our expectations, we found that early parental touch predicted only other-image, not self-image. Although the precise reason for this result was not clear, a prior study on childhood abuse and adult attachment demonstrated that two subscales—neglect and emotional abuse, and punishment and scolding—have a great influence on self-image, but not other-image (Liu et al. 2009). In this research, neglect and emotional abuse included such items as “Did your parents insult you or call you names?”, “Did your parents ever verbally lash out at you when you did not expect it?”, and “Did your parents ridicule you?” Punishment and scolding included, “Did your parents yell at you?”, “How often did your parents get really angry with you?”, and “Did your parents blame you for things you did not do?” We speculate therefore that verbal communication between parent and child, for instance involving praise and scolding, may be associated primarily with self-image, while physical contact such as interpersonal touch or hugs may be related to other-image. To further test this hypothesis, more precisely designed research is needed in the future.

Few studies on physical contact and depression have been published, with the exception of Cochrane (1990) who suggested that unsatisfactory physical contact was generally linked to a high incidence and severity of depression. Given this scarcity of data, another goal of the present study was to further explore the relationship between interpersonal touch and depression. Our results echoed those of Cochrane (1990) in that depression was significantly predicted by parental interpersonal touch throughout childhood. Although peer interpersonal touch failed to predict depression directly, it had an indirect influence on depression by high covariance with parental interpersonal touch. The degree to which parents initiate physical contact with their children is regarded as an important characteristic of parenting style. Indeed, the present results are consistent with Narita et al.’s (2000) findings that perceived parenting in childhood, as assessed by the Parental Bonding Instrument, predicted a lifetime history of depression. We also hypothesized that self-and other-images may serve as mediators that influence the relationship between interpersonal touch and depression. The present results failed to support this hypothesis, as there was no significant path between Interpersonal touch and self-image or between other-image and Depression. However, the connection seen between attachment and depression was in accordance with the prior research (Liu et al. 2009). Self-image can be considered as a moderator that has an effect on the relationship between interpersonal touch and depression.

Limitations of this study should be noted. First, the sample consisted only of university and college students. Thus, others of the same generation who were working, rather than in school, were not included. Furthermore, our findings should not be generalised to other age ranges or to clinical cases, and women outnumbered men in this study. Drawbacks of the methodology used in this study include an exclusive reliance on self-report as well as possible same-ratter bias. Theoretically we posited that adult attachment would predict depression. However, because this was a cross-sectional study, we could exclude the possibility of reversed casualty. Moreover, adult attachment style and depression may comprise a single trait. These possibilities should be studied in multiwave studies where both adult attachment style and depression are measured on more than one occasion.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that interpersonal touch with parents during childhood has an important influence on the development of depression and attachment during later adolescence and early adulthood.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1979). Attachment as related to mother-infant interaction. Advances in the Study of Behaviour, 9, 2–52.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Andersen, P. A., & Leibowitz, K. (1978). The development of nature of construct touch avoidance. Environment Psychology and Nonverbal Behavior, 3, 89–106.

Anisfeld, E., Casper, V., Nozyce, M., & Cunningham, N. (1990). Does infant carrying promote attachment? An experimental study of the effects of increased physical contact on the development of attachment. Child Development, 61, 1617–1627.

Arbuckle, J. L., & Wothke, W. (1955). Amos 4.0 user’s guide. Chicago: SmallWaters.

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationhip to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 427–454.

Armsden, G. C., McCauley, E., Greenberg, M. T., Burke, P. M., & Mitchell, J. R. (1990). Parent and peer attachment in early adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18, 683–697.

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Baer, J. C., & Maritez, C. D. (2006). Child maltreatment and insecure attachment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 24, 187–197.

Banmen, J. (1986). Virginia Satir’s family therapy model. Individual Psychology: Journal of Adlerian Theory, Research Practice, 42, 480–492.

Barnard, W. A., & Bell, P. A. (1982). An unobtrusive apparatus for measuring interpersonal distance. Journal of General Psychology, 107, 85–90.

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147–178.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowiz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226–244.

Beatson, J., & Taryan, S. (2003). Predisposition to depression: The role of attachment. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37, 219–225.

Bell, S. M., & Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1972). Infant crying and maternal responsiveness. Child Development, 43, 1171–1190.

Belsky, J., & Cassidy, J. (1994). Attachment: Theory and evidence. In M. Rutter & D. Hay (Eds.), Development through lives: A handbook for clinicians (pp. 373–402). Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Bifulco, A., Moran, P. M., Ball, C., & Bernazzani, O. (2002). Adult attachment style. I: Its relationship to clinical depression. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 37, 50–59.

Blatt, S. J. (1974). Levels of object representation anaclitic and introjective depression. Psychoanalytic Study of Child, 29, 107–157.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss (Vol. 1). Attachment. New York: Hogarth Press.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Separation: Anxiety and anger (Vol. 2). New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss. Loss sadness and depression (Vol. 3). New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). Developmental psychiatry comes of age. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 1–10.

Burgoon, J. K., Buller, D. B., Hale, J. L., & de Turk, M. A. (1984). Relational messages quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 644–663.

Cochrane, N. (1990). Physical contact experience and depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 82(s357), 19–23.

Collins, N. R., & Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 644–663.

Deethardt, J. F., & Hines, D. G. (1983). Tactile communication and personality differences. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 8, 143–156.

Egeland, B., & Farber, E. A. (1984). Infant-mother attachment: Factors related to its development and changes over time. Child Development, 55, 753–771.

Field, T. (1995). Massage therapy for infants and children. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 16, 105–111.

Field, T., Schanberg, S., Scafidi, F., Bauer, C. R., Vega-Lahr, N., Garcia, R., et al. (1986). Tactile/kinesthetic stimulation effects on preterm neonates. Pediatrics, 77, 654–658.

Finzi, R., Cohen, O., Sapir, Y., & Weizman, A. (2000). Attachment styles in maltreated children: A comparative study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 31, 113–128.

Fromme, D. K., Jaynes, W. E., Taylor, D. K., Hanold, E. G., Daniell, J., Rountree, J. R., et al. (1989). Nonverbal behavior and attitudes toward touch. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 13, 3–14.

George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1985). The Berkeley adult attachment interview. Unpublished protocol: University of California at Berkeley.

Griffin, D. W., & Bartholomew, K. (1994). The metaphysics of measurement: The case of adult attachment. In K. Bartholomew & D. Perlman (Eds.), Advances in personality relationship: Attachment processes in adulthood (Vol. 5, pp. 17–52). London, England: Jessica Kingsley.

Grossman, K., Grossman, K. E., Spangler, G., Suess, G., & Unzner, L. (1985). Maternal sensitivity and newborns’ orientation responses as related to quality of attachment in Northern Germany. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, 233–256.

Guerrero, L. K., & Andersen, P. A. (1991). The waxing and waning of relational intimacy: Touch as a function of relational stage, gender and touch avoidance. Journal of Social and Personal relationship, 8, 147–165.

Harlow, H. F. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 673–685.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524.

Johnson, K. L., & Edwards, R. (1991). The effects of gender and type of romantic touch on perceptions of relational commitment. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 15, 43–55.

Jones, S. E., & Brown, B. C. (1996). Touch attitudes and behaviours, recollections of early childhood touch, and social self-confidence. Journal of Nonverbal Behaviour, 20, 147–163.

Kenny, M. E., Lomax, R., Brabeck, M., & Fife, J. (1998). Longitudinal pathways linking adolescent report of maternal and paternal attachment to psychological wellbeing. Journal of Early Adolescence, 18, 221–243.

Korner, A. F., & Grobstein, R. (1966). Visual alertness as related to soothing in neonates: Implications for maternal stimulation and early deprivation. Child Development, 37, 867–876.

Kuethe, J. L. (1962a). Social schemas. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 64, 31–38.

Kuethe, J. L. (1962b). Social schemas and the reconstruction of social object displays from memory. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 65, 71–74.

Liu, Q., Nagata, T., Igarashi, H., Uji, M., & Kitamura, T. (2009). Effects of child abuse history on adult attachment style and depression: A study of a university student population in Japan. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Liu, Q., Nagata, T., Shono, M., & Kitamura, T. (2009b). The effects of adult attachment style and negative life events on daily depression: A sample of Japanese university students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 639–652.

Liu, Q., Shono, M., & Kitamura, T. (2008). The effects of perceived parenting and family functioning on adult attachment: A sample of Japanese university Students. Open Family Studies Journal, 1, 1–6.

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, 66–104.

Marcus, R. F., & Betzer, P. D. S. (1996). Attachment and antisocial behavior in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 16, 229–248.

Matsuoka, N., Uji, M., Hiramura, H., Chen, Z., Shikai, N., Kishida, Y., et al. (2006). Adolescents’ attachment style and early experiences: A gender difference. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9, 23–29.

Minzenberg, M. J., Poole, J. H., & Vinogradov, S. (2006). Adult social attachment disturbance is related to childhood maltreatment and current symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194, 341–348.

Montagu, A. (1986). Touching: The human significance of the skin (3rd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Narita, T., Sato, T., Hirano, S., Gota, M., Sakado, K., & Uehara, T. (2000). Parental child-rearing behavior as measured by the parental bonding instrument in a Japanese population: Factor structure and relationship to a lifetime history of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 57, 229–234.

Pedersen, D. M. (1973). Development of a personal space measure. Psychological Reports, 32, 527–535.

Pisano, M. D., Wall, S. M., & Foster, A. (1986). Perceptions of nonreciprocal touch in romantic relationships. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 10, 29–40.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CSE-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Rosenfarb, I. S., Becker, J., & Khan, A. (1994). Perceptions of parental and peer attachments by women with mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 637–644.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8, 23–74.

Spitz, R. (1945). Hospitalism: An inquiry into the genesis of psychiatric conditions in early childhood. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 1, 53–74.

Sroufe, L. A., Carlson, E., & Shulman, S. (1993). Individuals in relationships: Development from infancy through adolescence. In D. Funder, R. Parke, C. Tamlinson-Keasey, & K. Widaman (Eds.), Studying lives through time (pp. 315–342). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Tanaka, N., Hasui, C., Uji, M., Hiramura, T., Chen, Z., Shikai, N., et al. (2008). Correlates of the categories of adolescent attachment styles: Perceived rearing, family function, early life events, and personality. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62, 65–74.

Willis, F. N., & Briggs, L. F. (1992). Relationship and touch in public settings. Journal of Nonverbal Behaviour, 16, 55–63.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan: “Assessment and education for acceptability’s or bodily attachment at care-taking scene between the stuff and the client” (C-14510180).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Takeuchi, M.S., Miyaoka, H., Tomoda, A. et al. The Effect of Interpersonal Touch During Childhood on Adult Attachment and Depression: A Neglected Area of Family and Developmental Psychology?. J Child Fam Stud 19, 109–117 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9290-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9290-x