Abstract

We examined the associations between perceived parental rearing, attachment style, self-concept, and mental health problems among Japanese adolescents. About 193 high school students (143 boys and 50 girls, mean = 16.4) completed a set of self-report questionnaires including EMBU-C (My Memories of Child Upbringing for Children), AQC (Attachment Questionnaire for Children), SDQII-S (Self-Description Questionnaire II-Short) and YSR (Youth Self-Report). There seems to be a unique influence on mental health problems from parent–adolescent relations depending on the gender of parents and adolescents. PLS (Partial Latent Squares Regression) analysis showed that insecure attachments (Avoidant and Ambivalent) and Rejection from parents were predictors of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems among boys, while all dysfunctional parenting (Rejection, Overprotection and Anxious Rearing) were determinants of these problems among girls. Non academic self-concept (social, emotional, and physical) was a predictor of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. Power of the prediction of these problems was greater for girls than boys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parent–child relationships frequently undergo transitions during adolescence (e.g., Wissink et al. 2006). The way the parents raise their children and adolescents influences the personality development and potential risk of mental health problems in adulthood. Over the last two decades, extensive research on attachment pattern shows that early life experiences and attachment styles (e.g., Bowlby 1980) play important causative roles in psychopathology among adolescents (e.g., Markiewicz et al. 2006). Closely related to attachment pattern is an assessment of parental rearing behaviors. For example, Baumrind’s (1966) developed dimensions of parenting styles: authoritative (high demandingness and responsiveness), authoritarian (high demandingness and low responsiveness), and permissive (low demandingness and high responsiveness). Authoritarian parenting has been found to be more effective in collectivistic cultures (e.g., Chao 1994). To a great degree, culture influences the parental styles as well as the development of emotions and self-concept/self-esteem (Diaz 2005), and it has to be taken into account when using the Western developed instrument in Non-Western populations. Measures of parenting developed in the West (Parker et al. 1979) have been found to have different factor structures when used with Japanese samples (Uji et al. 2006). Uji et al. (2006) stated that this may reflect the fact that the concept of individual independence and autonomy is not very deeply rooted in Japanese culture, and that behaviors perceived as allowance of autonomy/independence by Westerns may be perceived as consideration or benevolent care of Japanese. This could be interpreted as an expression of the Japanese person’s psychological organization of “amae” (Doi 1973). Amae means “to depend and presume upon another’s love or back in another’s indulgence” (p. 8), and is “what an infant feels when seeking his or her mother” (p. 7). This amae-based symbiotic harmony continues in later childhood and adulthood in interpersonal relationships among Japanese (Doi 1973).

A cross-cultural study has shown that Japanese adolescents reported higher emotional ties to their mothers (Huang et al. 1996), and less emotional ties to their fathers compared to their American counterparts (Onodera 1993). As fathers influence their children indirectly through mothers (Shwalb et al. 1997), Japanese children feel more emotionally close to their mothers than to their fathers (Hatta 1994). In recent years, there has been a tendency for Japanese parents to be overprotective (Kimura 2007). As these different parenting styles and the idea of amae exist in the Japanese culture, there has been a debate about the universality of the fundamental tenets of the attachment theory. For example, Rothbaum et al. (2001) provided the cultural relativity of core hypothesis of attachment theory. Such aspects as sensitivity, competence, and secure base of attachment, which emphasize the child’s autonomy, individuation and exploration are viewed differently in Japan. However, Gjerde (2001) argued that these constructs are not compromised in cultures in which sensitivity and competence are experienced and expressed differently.

In Western countries, studies have shown that lower levels of perceived parental emotional warmth and higher levels of rejection and overprotection were linked to increased mental health problems in adolescents (e.g., Bosco et al. 2003; Muris et al. 2003b; Veenstra et al. 2006). Parental rejection and excessive authoritarian control before the age of eight were predictive of the level of the child’s self-criticism at age 12 and 13 (Koestner et al. 1991), and of the level of depression when the child is in late adolescence or young adulthood (Gjerde et al. 1991). Parental rejection was associated with problem behaviors among both delinquent and control groups of Russian adolescents (Ruchkin et al. 1998). Studies in Japan have shown that emotional distance to parents was greater among delinquent adolescents than their non-referred counterparts (Hatta et al. 1993), and that a combination of parental low-care and over-protection was found to be a risk factor for lifetime depression (Sato et al. 1997). A cross-cultural study indicated both cultural similarities and differences in the patterns of associations among family relations and adolescent problem behaviors in the United States, China, Korea and Czech Republic (Dmitrieva et al. 2004). Studies showed a unique influence of gender of parents and children (e.g., fathers vs. mothers, boys vs. girls) (Bosco et al. 2003; McKinney et al. 2008; Roelofs et al. 2006; Shek 2005; Werner and Silbereisen 2003). For example, boys reported more Externalizing Problems if they had negative perceptions of their mothers, while girls exhibited Internalizing Problems when they perceived both father and mother as negative (Bosco et al. 2003). Gjerde and Shimizu (1995) found that mother-son cohesion appeared as a less desirable characteristic of adolescents as the mother may become too involved or too protective of her son. Therefore, their result was shown that Japanese boys who were closely aligned with their mothers, and whose parents disagreed with their socialization practice, were more likely to have adjustment problems compared to the girls (Gjerde and Shimizu 1995). Studies on the effect of parent–adolescents’ gender in parent–adolescent relationships seem to be relatively new (Laible and Carlo 2004), and child reports on parental modeling of anxious behaviors are studied infrequently in different cultural groups (Wood et al. 2003).

Parental acceptance and warmth for children promote children’s positive attitudes towards self (Decovic and Meeus 1997). Studies have shown associations between parent relations and various self-concepts (i.e., appearance, school, physical) (Hay and Ashman 2003; Lau and Leung 1992), and between experiences of parental rejection and low self-esteem (Garber et al. 1997; Wind and Silvern 1994). Male adolescent self-concept was found to be more affected by the level of parental control and autonomy, while the female adolescent self-concept was more related to parental support and cooperation (Decovic and Meeus 1997). Emotional warmth from parents seemed to be the protective factor from the development of dysfunctional self, and overprotection and rejection from parents were related to dysfunctional perception of self and others (Andersson and Perris 2000). Kenny et al. (1993) found self as a mediator between attachment and depression.

During adolescence, attachment component transfers from parents to peers, and secure base functions were still primarily with parents, especially mothers, in late adolescence to adulthood (e.g., Markiewicz et al. 2006). Some researchers (e.g., Hazan & Shaver 1994) suggest that peer relationship can be conceptualized as the attachment relationship of adolescents. Peer attachment and parental rearing behavior accounted for a unique proportion of the variance in the case of Internalizing Problems (Muris et al., 2003b), and in both Internalizing and Externalizing Problems (Roelofs et al. 2006). Matsuoka et al. (2006) showed that care from Japanese fathers and less overprotection from the mother predicted a positive attachment among male adolescents, while higher care from both parents and less overprotection from mother predicted positive attachment among the female adolescents. Recently, Tanaka et al. (2008) demonstrated that a variety of psychosocial variables (i.e., perceived rearing, attachment, family function) were potent determinants of adult attachment. They included intrafamilial and extrafamilial variables: variables that dated back to the early days of life and those that are current among university students in Japan. Despite these cultural differences, some studies (e.g., Rohner and Britner 2002) evidenced a universal relationship between perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment and mental health problems across the cultures. However, compared to the large body of research concerning adolescent-parent relations and attachment style in Western countries, proportionately less research has been reported in non-Western countries regarding different aspects of the self and positive/negative impact on the adolescent psychological well-being from perceived parenting.

The main aims of the present study were (1) to examine the associations between the perceived parental rearing, attachment styles, self-concept, and mental health problems reported by Japanese adolescents, (2) to explore the influence of gender, and finally (3) to investigate the predictive power of perceived parenting, attachment style and self-concept for mental health problems in Japanese adolescents. From previous research and theoretical points of view, our hypothesis were that perceived parental emotional warmth and secure attachment would be positively associated with various self-concepts, but negatively associated with mental health problems and insecure attachments (Avoidant and Ambivalent). The dysfunctional parenting (i.e., Rejection, Overprotection and Anxious Rearing) would be negatively associated with self-concepts, but positively associated with mental health problems. There would be predictive relationships between perceived parenting styles, attachment style, self-concept, and mental health problems. We also expect some gender-specific relationships between parental rearing and variables depending on gender of adolescents and their parents.

Method

Participants

This study involved 193 adolescents (143 boys and 50 girls) attending public high school in middle-class neighborhoods (total inhabitants 255,765) in Japan. The mean age was 16.4 years (range = 15–19; SD = .96). Of the total sample of 268 students, 46 students (17.2%) who lived with only one parent were excluded as well as 29 students (10.8%) due to absence. The response rate was 72%. Based on information provided by the school, a majority of the students’ socioeconomic backgrounds were from middle class families.

Instruments

Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran—for Children: My Memories of Child Upbringing (EMBU-C)

Based on the original EMBU (Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran: My memories of child upbringing; Perris et al. 1980), Muris et al. (2003) developed this self-report instrument for measuring children and adolescents’ current perceptions of parental rearing. The EMBU-C consists of 40 items assessing adolescents’ perceptions of parent behavior across four domains: Emotional Warmth, Rejection, Overprotection, and Anxious Rearing. In the present study, a negatively worded item of overprotection (item number 24) “My parent(s) allows me to do everything” was excluded due to negative item-scale correlation to the other items in the scale of Overprotection. Consequently, the EMBU-C in the present study contained 39 items that were to be answered on 4-point Likert-scales (1 = No, never, 2 = Yes, but seldom, 3 = Yes, often, 4 = Yes, most of the time). The EMBU-C has been found to be a reliable and valid questionnaire for assessing the main dimensions of parental rearing (Muris et al. 2003a). A higher score of Emotional Warmth means more functional parenting while a higher score in Rejection, Overprotection and Anxious Rearing is interpreted as more dysfunctional parenting. Two dimensions, “control” (high loadings of Anxious Rearing and Overprotection and moderate loadings of Rejection), and “care” (high positive loadings of Emotional Warmth and high negative loadings of Rejection), were identified in the EMBU-C (Muris et al. 2003a). First, the participants rated the father’s rearing behavior and then the mother’s rearing behavior.

Attachment Questionnaire for Children (AQC)

AQC is a simplified age-downward version of Hazan and Shaver’s (1987) single-item measure of attachment style developed by Sharpe et al. (1998). Adolescents are provided with three descriptions (secure, avoidant, and ambivalent) concerning their feelings about and perception of relationships with their friends and peers. The ratings were made on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = disagree to 6 = agree, then one item was selected that best described them. Various studies (e.g., Muris et al. 2003b; Sharpe et al. 1998) yielded good validity by showing theoretically meaningful relations with other attachment indexes and psychopathology in youth. In the present study, the word “children” in AQC was changed to “students” in order to make it more suitable for the adolescents.

Self-Description Questionnaire II-Short (SDQII-S)

The SDQII-S (Marsh et al. 2005) is a 51-item self-report inventory that has been modified from the original 102-item SDQII (Marsh 1992) to measure junior and senior high school age self-concept in the following areas: Non-academic Self (Physical, Appearance, Same-sex Relations, Opposite-sex Relations, Parent Relations, Emotional Stability, and Honesty-trustworthiness), Academic-self (Math, Verbal, and School), and Self-esteem. The Total self-concept score is the sum of the different subscales. The participants respond on a six-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 = false to 6 = true; where the higher score means a more positive self-concept. The psychometric properties of the Japanese SDQII-S were sufficient (see Nishikawa et al. 2008). However, a disadvantage in the Marsh theoretical model of the multidimensional self-concept (Marsh 1992), is that parental relations is a single unit including ratings of both father and mother.

Youth Self Report (YSR)

YSR (Achenbach 1991) is a widely used self-report questionnaire designed for use with adolescents between the ages of 12 and 18. YSR contains 112 items that measure (a) eight narrowband sub-scales (Withdrawn, Somatic Complaints, Anxious/Depressed, Social Problem, Thought Problem, Attention Problem, Aggressive Behavior, Delinquent Behavior), (b) two broadband scales: Internalizing Problems (Withdrawn, Somatic Complaints, and Anxious/Depressed) and Externalizing Problems (Aggressive Behavior, and Delinquent Behavior). The Total Problems scale measures the overall behavioral and emotional functioning of the adolescents. The participants score their response on a three-point scale from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). A higher score means more emotional/behavioral problems. This instrument has already been validated and showed sufficient results in Japan (Kuramoto et al. 2002).

Procedures

Japanese YSR was provided from the National Institute of Mental Health (National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry) in Japan. The EMBU-C, the SDQII-S and AQC were translated by the author, whose native language is Japanese. Back translations as well as the pilot study for testing the questionnaires were also conducted. Permission for conducting the study was given by a school director. School classes were selected by the school director. The students filled in the questionnaire in regular class hours reserved for the study. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. It took approximately 30 min to complete. The questionnaires were conducted during summer of 2005.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS (The Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 16.0 was used for computing descriptive statistics, correlations, and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). The prediction of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems was analyzed by means of the multivariate projection method Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS), which is a regression extension of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (e.g., Henningsson et al. 2001; Wold et al. 1983). This predictive method is an alternative to OLS regression. The advantage of the PLS regression is that it can cope with multicollinearity that OLS regression does not, and is useful when exceeding the numbers of the cases. It extracts a set of latent factors that explain as much of the covariance as possible between the independent and dependent variables. The statistical significance of each component is determined by cross-variation criteria to avoid overfitting of the model. The Q 2 value (the goodness of prediction) is a measure of how well the independent variables X can predict the Y variables, when new cases are added. A Q 2 value larger than 0.1 of a component indicates significance of the model. The relative contribution from each independent variable to the PLS model is expressed in a Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) value. A VIP value larger than 1.0 contributes more than average to the relationship, while VIP values below 0.8 give only a minor contribution to the model.

Results

Psychometric properties of the Japanese EMBU-C. This Japanese version was found to be reliable in terms of the internal consistency (Cronbach alpha) ranging between .76 and .88 for different parent rearing styles. A principal components factor analysis with Oblimin rotation was carried out on the 39 items, father and mother separately, explained as 48 and 49% of the variance respectively, which corresponds to the original of 37% for fathers 35% for mothers (Muris et al. 2003a). Almost all items loaded substantially on their intended factors. The loadings of ratings of fathers and mothers were highly similar. Additionally, a corresponding confirmatory factor analysis of father and mother jointly was performed with two factors explaining 37% of the variance (original: 69%; Muris et al. 2003a). As with the original version, the factor labeled as “control” had high loadings on Overprotection and moderate loadings on Rejection, and “care” had positive loadings on Emotional Warmth and negative loadings on Rejection. However, Overprotection and Anxious Rearing also loaded, to some degree, in the “care” factor.

The correlations between the parenting styles showed that Anxious Rearing was positively correlated with Overprotection (rs between .74 and .76; all p < .01 and .05), Rejection (rs between .30 and .35; all p < .01 and .05) and Emotional Warmth (rs between .67 and .68; all p < .01 and .05), and Rejection was positively correlated with Overprotection (rs between .50 and .53; all p < .01 and .05). These results were similar across gender. T-test calculations revealed that mothers were rated as more anxious [t(184) = −5.63, p < .001], overprotective [t(171) = −5.38, p < .001], emotionally warm [t(171) = −4.31, p < .001], and rejecting [t(183) = −2.47, p < .005] than fathers.

Associations between Perceived Parental Rearing and the main areas of Self-concept. The self-concept scales were significantly associated with Emotional Warmth and Rejection (Table 1). Emotional Warmth from mother and father were positively associated with Self-esteem, Nonacademic Self and Total Self (rs between .18 and .36; all p < .01 and .05). Emotional Warmth of mothers and self-concepts (Self-esteem, Academic, Non academic, and Total Self) were associated (r = .20 to .42, p < .05 and .01) among the boys. For girls, Rejection from the fathers was negatively associated with Nonacademic and Total Self (r = −.42 and .45, respectively, p < .05 and .01), which was not shown among the boys.

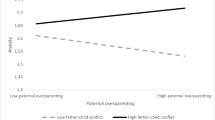

Associations between Perceived Parental Rearing and Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. Parental Overprotection, Rejection and Anxious Rearing were positively associated with Internalizing, Externalizing and Total Problems (rs between .19 and .38; all p < .01 and .05) (Table 2). There was a tendency that the overall strength of the associations was stronger for girls than for boys. Boys showed less pronounced associations of Overprotection and Anxious Rearing than girls in relation to mental health problems, especially concerning Externalizing Problems.

Associations between Perceived Parental Rearing and Attachment Style. Avoidant attachment was negatively associated with Emotional Warmth from father and mother (both r = −.21; p < .01), and positively associated with maternal Rejection (r = .17; p < .05) (Table 3). Ambivalent Attachment was positively associated with parental Rejection, and maternal Overprotection as well as maternal Anxious Rearing (rs between −.15 and .21; all p < .01 and .05). Similar results were found among boys and girls.

Attachment effect on Perceived Parental Rearing. Univariate F-test showed significant effects of attachment style for Overprotection Father [F (2,144) = 6.72, p < 0.05, Eta2 = 0.54, power = 0.72], Overprotection Mother [F (2,144) = 4.41, p < 0.05, Eta2 = 0.60, power = 0.75], Rejection Father [F (2, 144) = 3.71, p < 0.05, Eta2 = 0.05, power = 0.67], Anxious Rearing Father [F (2, 144) = 5.14, p < 0.01, Eta2 = 0.04, power = 0.64], and Anxious Rearing Mother [F (2, 144) = 4.33, p < 0.05, Eta2 = 0.57, power = 0.75]. There was a significant gender effect on Emotional Warmth Mother [F (2,144) = 273.52, p < 0.05, Eta2 = 0.36, power = 0.34]. Girls perceived more maternal emotional warmth than boys. Post-hoc comparisons revealed that ambivalent attached adolescents perceived their parents as more overprotective, anxious, and rejecting compared to the securely attached adolescents. There were slightly significant gender and attachment interactions on parental Emotional Warmth and Rejection, and paternal Anxious Rearing (p < 0.05).

Regressions Using the PLS Analysis

As a last step PLS analyses were conducted for boys and girls separately in order to examine the predictive relationship between perceived parental styles, attachment, self-concept (X), and mental health problems (i.e., Internalizing and Externalizing Problems)(Y) .

Table 4 shows the most important predictor variables (VIP values > 0.80) positively associated with Internalizing Problems among boys and girls. The results of the PLS analysis for boys showed one significant component in which 22.4% of the variance in the X variables predicted 29.9% of the variance in Internalizing Problems with a Q 2 value of 0.24. The pattern of the most important variables positively associated with high Internalizing Problems for boys were, insecure attachment (Avoidant and Ambivalent), parental Rejection and, to a lesser degree, Overprotection by the father. Negatively associated with Internalizing Problems were the different self-concepts. In girls, the corresponding PLS analysis also revealed one significant component, in which 28.0% of the variance in the X variables predicted 62.4% of the variance in Internalizing Problems with a Q 2 value of 0.54. In contrast to the boys, the most pronounced variables for girls were all the three dysfunctional parenting styles for both mother and father (i.e., Overprotection, Rejection and Anxious Rearing) together with an ambivalent attachment style. Different self-concepts were negatively related to Internalizing Problems.

The results of the PLS analysis for boys’ and girls’ Externalizing Problems (Table 5) showed one significant component in which 19.2% of the variance in the X variables predicted 22.6% of the variance in Externalizing Problems with a Q 2 value of 0.17. Boys’ Externalizing Problems were positively associated with a pattern of parental Rejection, Ambivalent Attachment, but also Anxious Rearing by both mother and father. In girls, the corresponding PLS analysis revealed one significant component, in which 23.8% of the variance in the X variables predicted 54.2% of the variance in Externalizing Problems with a Q 2 value of 0.43. Girls’ perceived Overprotection, Rejection and Anxious Rearing from both mother and father, and Emotional Warmth from fathers contributed the association with Externalizing Problems, while Total Self and Parent Self-concept were associated with low Externalizing Problems.

Discussion

We examined the relationships between perceived parenting, attachment style, self-concept, and mental health problems among Japanese high school students. The main results were that perceived dysfunctional parental rearing (particularly Rejection and Overprotection) and insecure attachments were associated with a lower self-concept and more mental health problems, in support of previous Western studies where perceived parenting as psychologically controlling and restrictive were associated with more emotional/behavioral problems (Bosco et al. 2003; Muris et al. 2003b; Wyman et al. 1999), negative self-concept (Hay and Ashman 2003; Lau and Leung 1992), and insecure attachments (Matsuoka et al. 2006; Muris et al. 2003b). Consistent with early studies (e.g., Uji et al. 2006), girls rated higher Emotional Warmth from mothers than boys. All ratings of both positive and negative parenting of mothers were significantly higher than those of fathers across gender. We observe this result to reflect the fact that mothers have more interactions with their children compared to the fathers. Despite few gender differences in the mean rate of the perceived parental rearing behaviors, our study showed gender-specific associations, in contrast to Western findings of Muris et al. (2003b) who found similar associations across gender. The magnitude of correlations between perceived parenting and mental health problems were stronger for the girls than for boys, in spite of a smaller sample size of the girls. In addition, the multivariate analysis showed similar results, namely that the girls’ goodness of prediction value (Q 2) appeared to be stronger than the boys’ values in both Internalizing (0.24 and 0.54 for boys and girls, respectively) and Externalizing Problems (0.23 and 0.42 for boys and girls, respectively). Also, lower Non-academic self-concept was a predictor of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. The pattern of parenting and attachments in the prediction of mental health problems also differed according to gender. For the Japanese boys, insecure attachments (Avoidant and Ambivalent) together with parenting rejection were predictors of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems, while for girls all three negative parental rearing styles (Rejection, Overprotection and Anxious Rearing) were important determinants of these problems. Similar results were found in studies from USA (Rogers et al. 2003), The Netherlands (Roelofs et al. 2006), and China (Shek 1999). The reasons for that may be that girls are more sensitive than boys to negative parenting, or parents may be more sensitive to girls’ behavior or that girls are more vulnerable than boys in gaining an individual autonomy especially from their mothers (Cauce et al. 1996). Consistent with the Western and Japanese studies (e.g., Matsuoka et al. 2006; McKinney et al. 2008), our results suggests that fathers’ parenting behavior towards adolescents is as important as the mothers’ for their well being.

The present study showed that Japanese EMBU-C is reliable for assessing adolescent perceptions of their parental behavior. The strength of the EMBU-C is that this instrument assesses adolescents’ perceptions of current rather than retrospective parenting behaviors.

Despite similar factor structures in EMBU-C in our Japanese version compared to the original form of the questionnaire (Muris et al. 2003a), the two dimensions of “care” and “control” appeared to be different. In more interdependent family patterns, the definition of “control” can range from parental hostility to warmth depending on social norms and practices (Kagitcibasi 2005), while “caring” and “warm” parenting behaviors are less influenced by culture (Uji et al. 2006).

It is important to acknowledge the limitations in our study. First, the excluded item of EMBU-C “My parent allows me to do everything” may be perceived differently by Japanese adolescents. Further investigation is necessary to understand the meaning of the item. Second, the present study was designed to be cross-sectional and hence does not provide any causal relationships. There may be bidirectional links with dysfunctional parenting styles resulting in emotional problems and a negative self-concept, which in turn further promote negative parental relations. Some longitudinal studies have indicated that parental rejection tends to precede the development of behavioral problems among adolescents (e.g., Chen et al. 1997). Shek (2007) indicated, over time, bidirectional links between parental psychological control and psychological well-being among adolescents. More longitudinal studies are needed in the future on these issues. Third, although AQC is easy to administer, this instrument may lead to underreporting of attachment patterns (Muris et al. 2003b) and not measure the four major attachment styles, i.e., secure, fearful avoidant, ambivalent, and dismissing avoidant (Bartholomew and Horowitz 1991). Fourth, the measurement of self-concept includes items that measure adolescents’ perceptions of their relationship with their parents. It may inflate correlations between the some self-concept scales EMBU-C. We have however controlled the Parent self-concept and the results were almost the same. Finally, the small sample size limits the generalizability to Japanese adolescents as a whole. Also there were not equal numbers of girls compared to the boys. It can be said that there were more boys than girls in randomly selected classes.

In conclusion, our findings illustrated rather universal aspects of parental rearing (e.g., associations between parental rearing, attachment, self-concept and mental health), yet there also seems to be cultural specific aspects. That is the key question of cross-cultural study in the future. Wissink et al. (2006) found both similarities and differences in the associations between parent–adolescent relationships and mental health outcomes across ethnical groups, and suggested the importance of considering the cultural aspects in the meaning of parenting. The development and validation of self-report and parental-report, as well as interview based measures of parental rearing may be an important task for further exploration. At the same time, it is important to remember that other factors such as psychosocial influences have an impact upon parental rearing behaviors and children’s mental health problems during the adolescents’ lifespan.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the Youth Self-report and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Andersson, P., & Perris, C. (2000). Perceptions of parental rearing and dysfunctional attitudes: The link between early experiences and individual vulnerability? Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 405–409.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226–244.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37, 887–907.

Bosco, G. L., Renk, K., Dinger, T. M., Epstein, M. K., & Phares, V. (2003). The connections among adolescents’ perceptions of parents, parental psychological symptoms, and adolescent functioning. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24, 179–200.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss, vol 3. Loss: Sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books.

Cauce, A. M., Hiraga, Y., Graves, D., Gonzales, N., Ryan-Finn, K., & Grove, K. (1996). African American mothers and their adolescent daughters: Closeness, conflict, and control. In B. Leadbeater & N. Way (Eds.), Urban girls: Resisting stereotypes, creating identities (pp. 100–117). New York: New York University Press.

Chao, R. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development, 65, 1111–1119.

Chen, X., Rubin, K. H., & Li, B. (1997). Maternal acceptance and social and school adjustment in Chinese children: A four-year longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 43, 663–681.

Decovic, M., & Meeus, W. (1997). Peer relations in adolescence: Effects of parenting and adolescents’ self-concept. Journal of Adolescence, 20, 163–176.

Diaz, D. M. V. (2005). The relations among parenting style, parent–adolescent relationship, family stress, cultural context and depressive symptomatology among adolescent females. Doctoral dissertation, Georgia State University.

Dmitrieva, J., Chen, C., Greenberger, E., & Gil-Rivas, V. (2004). Family relationships and adolescent psychosocial outcomes: Converging findings from Eastern and Western cultures. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14, 425–447.

Doi, T. (1973). The anatomy of dependence: The key analysis of Japanese behavior. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Garber, J., Robinson, N. S., & Valentiner, D. (1997). The relation between parenting and adolescent depression: Self-worth as a mediator. Journal of Adolescent Research, 12, 12–33.

Gjerde, P. F. (2001). Attachment, culture, and amae. American Psychologist, 56, 826–827.

Gjerde, P. F., & Shimizu, H. (1995). Family relationships and adolescent development in Japan. Journal of Research on Adolescents, 5, 281–318.

Gjerde, P. F., Block, J., & Block, J. H. (1991). The pre-school family context of 18-year-olds with depressive symptoms: A prospective study. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 1, 63–91.

Hatta, T. (1994). Projected family structure by modem Japanese adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality, 22, 399–408.

Hatta, T., Kawakami, A., Tsukiji, N., Ayetani, N., Araki, T., & Shimizu, M. (1993). Family structure of Japanese juvenile delinquents: Evidence from the results of Doll Location test. Social Behavior and Personality, 21, 7–16.

Hay, I., & Ashman, A. F. (2003). The development of adolescents’ emotional stability and general self-concept: The interplay of parents, peers, and gender. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 50, 77–91.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1994). Attachment as an organizational framework for research on close relationships. Psychological Inquiry, 5, 1–22.

Henningsson, M., Sundbom, E., Armelius, B-Å., & Erdberg, P. (2001). PLS model building: A multivariate approach to personality test data. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 42, 399–409.

Huang, Y., Someya, T., Takahashi, S., Reist, C., & Tang, S. W. (1996). A pilot study of the EMBU scale in Japan and the United States. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 94, 445–448.

Kagitcibasi, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 403–422.

Kenny, M. E., Moilanen, D. M., Lomax, R., & Brabeck, M. M. (1993). Contributions of parental attachment to view of self and depressive symptoms among early adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 13, 408–430.

Kimura, K. (2007). Benesse 2010nen kodomo no kyoiku o kangaeru. [Benesse Year 2010: Considering child education.] Benesse Education Research Center: A message from researchers, 4. From http://benesse.jp/berd/berd2010/center_report/data03_02.html. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

Koestner, R., Zuroff, D. C., & Powers, T. A. (1991). The family origins of adolescent self-criticism and its continuity into adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 19, 1–197.

Kuramoto, H., Kanbayashi, Y., Nakata, Y., Fukui, T., Mukai, T., & Negishi, Y. (2002). Standardization of the Japanese version of the Youth Self-Report (YSR). Japanese Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 17–32.

Laible, D. J., & Carlo, G. (2004). The differential relations of maternal and paternal support and control to adolescent social competence, self-worth, and sympathy. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 759–782.

Lau, S., & Leung, K. (1992). Self-concept, delinquency, relations with parents and school, and Chinese adolescents’ perceptions of personal control. Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 615–622.

Markiewicz, D., Lawford, H., Doyle, A. B., & Haggart, N. (2006). Developmental differences in adolescents’ and young adults’ use of mothers, fathers, best friends, and romantic partners to fulfill attachment needs. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 127–140.

Marsh, H. W. (1992). Self-Description Questionnaire II: Manual. Australia: Faculty of Education, University of Western Sydney.

Marsh, H., Ellis, L., Parada, R., Richards, G., & Huebeck, B. (2005). A short version of the Self Description Questionnaire II: Operationalizing criteria for short-form evaluation with new applications of confirmatory analyses. Psychological Assessment, 17, 81–102.

Matsuoka, N., Uji, M., Hiramura, H., Chen, Z., Shikai, N., Kishida, Y., et al. (2006). Adolescents’ attachment style and early experiences: A gender difference. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9, 23–29.

McKinney, C., Donnelly, R., & Renk, K. (2008). Perceived parenting, positive and negative perceptions of parents, and late adolescent emotional adjustment. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13, 66–73.

Muris, P., Meesters, C. M. G., & Van Brakel, A. (2003a). Assessment of anxious rearing behaviors with a modified version of “Egna Minnen Besträffende Uppfostran” Questionnaire for Children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 25, 229–237.

Muris, P., Meesters, C. M. G., & Van den Berg, S. (2003b). Internalizing and externalizing problems as correlates of self-reported attachment style and perceived parental rearing in normal adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 12, 171–183.

Nishikawa, S., Hägglöf, B., & Sundbom, E. (2008). Correlates of self-concept, attachment style and internalizing and externalizing problems among high school students in Japan. Sweden: Umeå University. Unpublished manuscript.

Onodera, O. (1993). Comparative study of adolescent views on their parents and their self-reliance in Japan and the United States. Shinrigaku Kenkyu, 64, 147–152.

Parker, G., Tupling, H., & Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52, 1–10.

Perris, C., Jacobsson, L., Lindström, H., VonKnorring, L., & Perris, H. (1980). Development of a new inventory for assessing memories of parental rearing behaviour. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 61, 265–274.

Roelofs, J., Meesters, C., ter Huurne, M., Bamelis, L., & Muris, P. (2006). On the links between attachment style, parental rearing behaviors, and internalizing and externalizing problems in non-clinical children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 331–344.

Rogers, K. N., Buchanan, C. M., & Winchell, M. E. (2003). Psychological control during early adolescence: Links to adjustment in differing parent/adolescent dyads. Journal of Early Adolescence, 23, 349–383.

Rohner, R. P., & Britner, P. A. (2002). Worldwide mental health correlates of parental acceptance-rejection: Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal of Comparative Social Science, 36, 16–47.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Pott, M., Miyake, K., & Morelli, G. (2001). Deeper into attachment and culture. American Psychologist, 56, 827–828.

Ruchkin, V. V., Eisemann, M., Hägglöf, B., & Cloninger, C. (1998). Aggression in delinquent adolescents vs controls in northern Russia: Relations with hereditary and environmental factors. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 8, 115–126.

Sato, T., Sakado, K., Uehara, T., Nishioka, K., & Kasahara, Y. (1997). Perceived parental styles in patients with depressive disorders: Replication outside western culture. British Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 173–175.

Sharpe, T. M., Killen, J. D., Bryson, S. W., Shisslak, C. M., Estes, L. S., Gray, N., et al. (1998). Attachment style and weight concerns in preadolescent and adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorder, 23, 39–44.

Shek, D. T. L. (1999). Parenting characteristics and adolescent psychological well-being: A longitudinal study in a Chinese context. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 125, 27–44.

Shek, D. T. L. (2005). Perceived parental control and parent–child relational qualities in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Sex Roles, 53, 635–646.

Shek, D. T. L. (2007). A longitudinal study of perceived differences in parental control and parent–child relational qualities in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 156–188.

Shwalb, D. W., Kawai, H., Shoji, S., & Tsunetsugu, K. (1997). The middle class Japanese father: A survey of parents of preschoolers. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 18, 497–511.

Tanaka, N., Hasui, C., Uji, M., Hiramura, H., Chen, Z., Shikai, N., et al. (2008). Correlates of the categories of adolescent attachment styles: Perceived rearing, family function, early life events, and personality. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62, 65–74.

Uji, M., Tanaka, N., Shono, M., & Kitamura, T. (2006). Factorial structure of the parental bonding instrument (PBI) in Japan: A study of cultural, developmental, and gender influences. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 37, 115–132.

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Oldehinkel, A. J., De Winter, A. F., & Ormel, J. (2006). Temperament, environment, and antisocial behavior in a population sample of preadolescent boys and girls. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 422–432.

Werner, N. E., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2003). Family relationship quality and contact with deviant peers as predictors of adolescent problem behavior: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Adolescent Research, 18, 454–480.

Wind, T., & Silvern, L. (1994). Parental warmth and childhood stress as mediators of the long term effects of child abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 18, 439–453.

Wissink, I. B., Dekovic, M., & Meijer, A. M. (2006). Parenting behavior, quality of the parent–adolescent relationship, and adolescent functioning in four ethnic groups. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 26, 133–159.

Wold, S., Albano, C., Dunn, W. J., Esbensen, K., Hellberg, S., Johansson, E., et al. (1983). Pattern recognition: Finding and using regularities in multivariate data. In H. Martens & H. Russworm (Eds.), Food research and data analysis (pp. 147–188). London: Applied Science Publishers.

Wood, J. J., McLeod, B. D., Sigman, M., Hwang, W., & Chu, B. C. (2003). Parenting behavior and childhood anxiety: Theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 134–151.

Wyman, P. A., Cowen, E. L., Work, W. C., Hoyt-Meyers, L., Magnus, K. B., & Fagen, D. B. (1999). Caregiving and developmental factors differentiating young at-risk urban children showing resilient versus stress-affected outcomes: A replication and extension. Child Development, 70, 645–659.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nishikawa, S., Sundbom, E. & Hägglöf, B. Influence of Perceived Parental Rearing on Adolescent Self-Concept and Internalizing and Externalizing Problems in Japan. J Child Fam Stud 19, 57–66 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9281-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9281-y