Abstract

Objective assessment of child and adolescent behavioral and emotional symptoms is traditionally obtained from multiple sources. However, a substantial body of research indicates that parental and child reports provide significant amounts of contradicting diagnostic information. Although a large and growing body of research attempts to identify potential influences of discrepant reports, the current research improves upon previous research in three primary ways: using identical item measures, using expanded statistical analyses, and evaluating cultural influences on observed discrepancies. A total of 2,153 parent–child dyads completed ratings of child behavior and emotional functioning. Specifically, parents and children completed the Ohio Scales, an empirically supported, identical item measure. Generally, reporter agreement was greater than typically reported. Similar to previous research with clinical populations, parents reported greater levels of child problems than their children. While age was not associated with observed discrepancies, parents and daughters demonstrated greater discrepancies on fewer specific items while parents and sons demonstrated more pervasive yet less severe discrepancies. Additionally, Hispanic dyads demonstrated less discrepancy than did African American and Caucasian dyads independent of discrepancy analysis. Discrepancies must be measured using multiple statistical methods in order to understand patterns. Furthermore, discrepancy research must address key demographic factors (e.g., ethnicity, gender).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Both research and clinical practice have indicated that the assessment of children requires collection of data from multiple sources (Thompson et al. 1993). However, ample evidence also indicates that invariably discrepancies exist between the symptoms reported by each source (Achenbach et al. 1987; De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2005). Furthermore, discrepancies significantly impact areas such as diagnosis (Offord et al. 1996), treatment planning (Hawley and Weisz 2003; Yeh and Weisz 2001), and outcome assessment (Brookman-Frazee 2005; Carlston 2005). Given the prevalence and impact of reporter discrepancies, a large body of research seeks to identify patterns and trends associated with these discrepancies.

Early research has been summarized in Achenbach and colleague’s 1987 metaanalysis of 119 individual studies of inter-informant agreement. Three key findings regarding parent–child discrepancy were highlighted. First, parents and children were found to disagree more in their symptom reports than were the vast majority of alternative informant combinations (e.g., parent–parent, parent–teacher, teacher–observer). Second, only modest correlations between parent and child ratings of psychopathology were found. Third, several demographic and clinical factors impacted the strength of correlations between parent and child scores including child age and symptom domain. Subsequent research has endeavored to expand upon previously evaluated demographic and clinical factors associated with discrepancies.

Several child, parent, and family characteristics have been evaluated for their impact on parent–child discrepancies (Carlston 2005). Unfortunately, a number of problems plague the current body of literature. For example, there is little consistency in the measurement of discrepancies across studies (e.g., measures used, sample characteristics, statistical analyses, age distinctions). Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of research in reporter-discrepancies has been conducted using assessment devices that ask different questions of each reporter (Carlston and Ogles 2006). As a result of these weaknesses, the current body of literature lacks a foundation for identifying important correlates and processes associated with parent–child discrepancies on reports of problem behavior and emotional functioning. Therefore, the goal of the current research is to improve upon previous research in parent–child discrepancy research by evaluating reporter discrepancies using identical item measures and expanded statistical analysis.

Method

Subjects

To accomplish this goal, upon IRB approval, de-identified, archival data was obtained from the State of California Department of Mental Health. Specifically, the data included in this study represents administrative data collected by the Task Force for Selecting New Children’s Instruments during a pilot study to investigate changing the measures used in the state’s performance outcome measurement system. Obtained information included child age, gender, ethnicity, behavior reports, and primary diagnosis.

The procedure for data collection during the pilot study is detailed elsewhere (California Department of Mental Health 2000); however, a general overview of the sampling procedure is provided here. Upon development of the task force goals and objectives, several counties volunteered to participate in the data collection. Of those volunteering counties, a sample was selected for participation such that statewide coverage of demographic groupings (i.e., child age, gender, level of care, and region), county characteristics, and service characteristics was ensured. Furthermore, the obtained sample was selected in order to represent clinical characteristics similar to those observed across the statewide system. The current results are reported utilizing data collected in a fifteen month period beginning December 2000.

Instruments

Perhaps the simplest methodological weakness of previous research is the use of measures that solicit information using different questions for different reporters. When such measures are employed, discrepancy between parent and child reports may simply be the result of variability across items answered by each party (Epkins 1996; Rey et al. 1992; Schaefer et al. 1989). In other words, parents and children may provide discrepant information because they are answering intuitively similar yet subtly different questions. For example, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) asks parents to determine if their child is, “Underactive, slow moving, or lacks energy,” while the corresponding child question asks the child if s/he “[Doesn’t] have much energy.” While each of these questions addresses activity level, there are subtle and significant differences between the two items. While item variance is illustrated here in the CBCL, such variance is readily apparent across the majority of parent–child measures. Therefore, the current research represents a significant methodological improvement as it employs a measure of child behavior with identical items.

The Ohio Scales

The Ohio Scales are an empirically validated set of measures designed to generate essential information to service providers regarding current youth behavioral and emotional deficits (Ogles et al. 2001). As a family of measures, the Ohio Scales solicit information relevant to treatment outcome assessment from multiple stake holders (use of the Ohio Scales for this purpose is detailed for the reader elsewhere—Ogles et al. 2004). Pertinent stakeholders were identified as agency workers, parents, and children. Subsequently, the parent and agency worker form allow for reports of children ages 5–18 while the youth form was originally created for youth ages 12–18 (Ogles et al. 1998). During measure development, items were generated based upon DSM-IV criteria, surveys of commonly occurring symptoms and problems in of youth with SED, survey of existing measures, focus groups with service providers and a social validation survey (Ogles et al. 2001). Seventy-two items were identified and included in the Ohio Scales questionnaires. Following factor analysis of responses using the original measures, the Ohio Scales were shortened to include 20 problem severity items, 20 functioning items, 4 questions regarding hopefulness, and four questions regarding satisfaction with services. For the purposes of the current research, the Ohio Scales Short Forms were used for their brevity. Additionally, only the parent and child measures were used as they were germane to the specific research questions. Finally, the Ohio Scales Short Form has been found to produce consistent factor structure across parent and child forms (Baize 2001). The psychometric properties of the short forms for these two measures are presented briefly with appropriate references for additional information.

The short forms only the parent and child reports of problem behavior were utilized as these scales demonstrate strong internal consistency and reliability (Ogles et al. 2004). Specifically, the parent problem severity scale yielded an internal reliability estimates (Cronbach’s Alpha) of 0.91 and a 2-week test–retest reliability estimates of 0.88 while the youth measure yielded internal reliability estimates of .93 and test–retest reliability estimates of .72 (Ogles et al. 2004). The reliable change index for the Ohio Scales problem severity scale is 10 points. Several validation strategies were employed using the Ohio Scales Short Form (Ogles et al. 2001, 2004). Pertinent to the current research, ratings on the Ohio Scales Short Form were compared to commonly implemented measures. The parent scales were found to correlate significantly with ratings on both the Child Behavior Checklist and the Conner’s Parent Rating Scale (r = .85, p < .001 and r = .89, p < .05, respectively) while child ratings were found to significantly correlate with the Youth Self Report (r = .82, p < .05). Additionally, comparisons of parent and youth ratings from community samples (M = 10.29, SD = 9.88 and M = 18.18, SD = 15.04, respectively) were significantly lower than ratings of parents and youth from clinical samples (M = 39.35, SD = 17.71 and M = 36.31, SD = 20.96, respectively; Ogles et al. 2004).

Finally, the Ohio Scales Short Form was administered to children ages 9–18 and their parents. This represents a deviation from the instructions presented in the Technical Manual (Ogles et al. 2001). Research following the publication of the technical manual demonstrated that children ages 9–11 were able to complete the problem severity scales of the Ohio Scales Short Form (Dowell and Ogles in press). Therefore ratings of younger children were included in the present study in order to facilitate the analysis of age effects on discrepancy.

Demographic Information

In addition to the symptom reports collected vis-à-vis the Ohio Scales, key demographic data was obtained as well. Specifically, data regarding child age, gender, and ethnicity were obtained. In order to evaluate the impact of the proposed demographic variables on parent–child discrepancy, dyads were coded in terms of age (i.e., younger, older), gender (i.e., male, female), and ethnicity (i.e., Caucasian, African American, Hispanic).

While age has been incorporated into practically all previous studies of parent–child discrepancy, there has been virtually no consistency across studies regarding the determination of age groups. Rather than using a median split, as is employed in the majority of previous research, the current research classified children into two groups (ages 9–11 and 12–18). This cutoff was determined based upon common developmental theory (e.g., Oman et al. 2002) and to be consistent with previous research regarding adolescent age groups (e.g., Rousseau and Drapeau 1998; Yeh and Weisz 2001).

Measures of Discrepancy

Previous research has primarily evaluated discrepancy in two ways. First, discrepancies are evaluated using correlation comparisons. Correlation coefficients have been used to represent the degree to which parents and children agree on the relative severity of the child’s behavior and/or emotional experience. While this statistic provides extremely useful information regarding relative severity reports, differences in magnitude of severity are greatly masked when using the Pearson correlation. The actual degree of severity reported by either the parent or the child has a less of an impact on the obtained correlation coefficient than does the relative ranking of the severity rating. As a result, significant differences in the reported symptom severities across items are not readily apparent when using this method of analysis.

To evaluate discrepancies with greater attention to severity rather than rank, difference scores are often evaluated (i.e., the actual difference between parent and child total scores). These scores are useful in that in addition to demonstrating magnitude and direction of observed differences, they are inherently tied to severity ratings. On the other hand, as difference scores use total scores, they provide no item-level information. In other words, although a parent and child may produce identical problem total scores, parent and child responses to specific questions may vary significantly. For example, a parent may endorse all behavioral items while a child endorses all emotional items, yet their total scores could easily be identical. Unfortunately, the use of statistics targeting item-level variability is a glaring omission in the current discrepancy literature. Therefore, in addition to analysis of correlations and difference scores, the current research evaluates item level differences using d2 (the sum of squared parent and child item differences).

Results

Demographics

A total of 2,153 parent and child dyads participated in the current study. Dyads with missing data were excluded on an analysis by analysis basis. This decision was made due to the large sample size available and to attenuate any artificial findings which may occur when alternate scores are substituted form missing data. The majority of children were ages 12–18 (71.3%) and had a primary diagnosis of an internalizing disorder (57%). There was a relatively even gender split with 50.6% of the child sample male. 31.5% of the child sample was Caucasian, while 31.1% and 10% were Hispanic and African American respectively with the remaining children either not reporting ethnicity or of bicultural descent. Finally, the majority of parent reports were completed by biological parents (62.7%). Data regarding parental gender was unavailable.

Overall Parent vs. Child

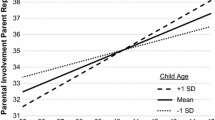

Descriptive data for the entire sample is presented in Table 1. As illustrated in Fig. 1, there is considerable variability in difference scores across dyads. In fact, discrepancy scores range from −58 points (children reporting greater symptoms than their parents) to 70 points (parents reporting greater symptoms than their parents). Furthermore, 41% of the dyads evidenced discrepancy scores greater than 10 absolute points, the cutoff for reliable change on the Ohio Scales problem severity scale.

Significant correlations were obtained between parent and child reports of total problem severity (r = 0.48, p < .001). Similarly, significant correlations were obtained when analyzing both the internalizing and externalizing factor (r = 0.46, p < .001, and r = 0.50, p < .001). A Fisher’s r-z transformation determined there were no significant differences in the magnitudes of correlation between parents and children on each of the factor scales (i.e., internalizing, externalizing).

Although moderately correlated, significant differences were obtained between the average parent and child ratings of total problem behavior (t(2152) = 8.03, p < .001). Specifically, parents rated their children’s behavioral and emotional problems as more severe than did their children. Follow up analyses were conducted in order to determine whether a similar pattern of discrepancy exists within each of the factor scores. Interestingly, parents and children, on the average, did not differ significantly in their reports of internalizing symptoms while parents reported greater levels of child externalizing behaviors than did their children (t(1562) = 8.42, p < .001; see Table 1).

Main Effects

In order to assess the impact of the three demographic variables (i.e., child age, gender, ethnicity), all main effects were analyzed. Each of the main effects was analyzed initially using the total problem score. When significant effects were identified based upon the total problem score, analyses of the internalizing and externalizing factors were conducted to determine whether similar patterns of discrepancy were evident within the individual factors.

Age Effects

Significant correlations were obtained between parent–child dyads within each developmental category for the total problem severity as well as each of the factor scores (see Table 2). No significant differences were obtained in the rates of correlation across age group.

In order to evaluate the impact of child development on parent–child agreement, a one-way ANOVA was conducted using difference scores between parent and child on the total problem factor. No significant effect for age was identified in any of the analyses. Therefore, item level discrepancy as measured by the total, squared, parent–child item differences was independent of child age.

Gender Effects

Significant correlations were obtained between parents and their daughters as well as parents and their sons for the total problem severity as well as each of the factor scores (see Table 3). No significant differences were obtained in the rates of correlation between parents and their male and female children.

In order to evaluate the impact of child gender on parent–child agreement a one-way ANOVA was conducted using the total problem reports of parents and children. A significant effect for gender on net differences between parent and child severity ratings was obtained using the total problem severity score (F(1, 1536) = 14.97, p < .001). Specifically, while parents’ ratings, in general, were more severe than child ratings, the degree of net differences between parent and child severity ratings was greatest between parents and their sons.

Second, given the significant difference found in the net differences between parent and child severity ratings based upon gender using the total problem score, two one-way ANOVA’s were conducted using parent and child difference scores on each of the factors. Significant discrepancy in the net differences between parent and child severity ratings of the internalizing (F(1, 1536) = 10.45, p < .001) and externalizing factors were obtained (F(1, 1536) = 12.53, p < .001). In each case, parents and sons were associated with greater net differences between parent and child severity ratings than were parents and their daughters.

Total, squared, parent–child item differences were used in a one-way ANOVA to determine significant item-level differences scores reported by parents and children on the total score problem severity score. A significant gender effect was obtained (F(1, 1536) = 4.92, p < .05). Specifically, greater total, squared, parent–child item differences were identified between parents and their daughters.

Given the significant main effect of gender on the total, squared, parent–child item differences, exploratory ANOVA’s were conducted using each of the measure factors. Significant gender effects were identified on the internalizing factor (F(1, 1536) = 9.55, p < .01). Again, scores generated by parents and their daughters were associated with greater total, squared, parent–child item differences than were scores produced by parents and their sons. No significant gender effects on generalized difference scores were found when analyzing the externalizing factor scores.

Ethnicity

Significant parent–child correlations were obtained for the problem severity total score across ethnic category (see Table 4). No significant differences between the correlations of parents and children across ethnic categories were detected when an r-z transformation was conducted.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to identify variability in the net differences between parent and child severity ratings of total problem symptom reports for parents and children of differing ethnic categories.

Ethnicity was found to significantly contribute to net differences in parent and child reports of total problem severity (F(2, 1560) = 19.29, p < .001). Post hoc LSD tests found Hispanic dyad agreement was significantly better than among Caucasian and/or African American dyads. No other significant differences in net differences between parent and child severity ratings were obtained using the total problem severity scores.

In order to explore the stability of these discrepancy patterns across the factor scores, two one-way ANOVA’s were conducted for each factor scores. Significant variability in discrepant reports were found across ethnic categories when evaluating the internalizing scores (F(2, 1560) = 8.11, p < .001). Once again, Hispanic dyads demonstrated unique discrepancy patterns relative to their Caucasian and African American counterparts. Specifically, Hispanic children were more likely to report greater internalizing symptoms than their parents while this is a pattern not seen in either the Caucasian or African American samples.

Analysis of the externalizing factor also found significant ethnicity effects (F(2, 1560) = 20.58, p < .001). Again, LSD tests found that Hispanic children and their parents were found to produce smaller net differences between parent and child severity ratings than their Caucasian, and African American counterparts. Given that the direction of agreement was consistent across ethnic categories it is possible to conclude that Hispanic children and their parents are associated with significantly less discrepancy when reporting externalizing child symptoms than are African American and Caucasian children and parents.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted using total, squared, parent–child item differences (d2). A trend for ethnicity effects on total, squared, parent–child item differences was obtained when evaluating the total problem severity score (F(4, 2143) = 4.323, p = .05). As a result, two one-way ANOVA’s using each of the factor scores were conducted in order to better understand the effect of ethnicity on parent–child discrepancy.

No significant ethnicity effects were obtained on the internalizing factor. However, significant ethnicity effects were obtained when evaluating the externalizing factor (F(2, 1560) = 3.11, p < .05). LSD post tests found that on the externalizing factor reports form Hispanic children and their parents were found to produce significantly lower total, squared, parent–child item differences than were reports form Caucasian and African children and their parents.

Interaction Effects

All four factors (i.e., child age, gender, symptom type, ethnicity) were included in a RMANOVA in order to determine significant interactions these demographic factors and discrepancy as measured by correlation, mean differences (d), and generalized distance scores (d2). While in all cases, the previously reported main effects were upheld, no significant second or third order interactions were identified between child age, gender, ethnicity, and symptom domain.

Discussion

We evaluated multiple statistical measures of discrepancies obtained on identical item reports. Although previous research has attended to one or the other of these methodological considerations (e.g., Carlston and Ogles 2006; Epkins 1996; Youngstrom et al. 2000), no research to date has done both. Following is a brief discussion of the findings from the current research.

First, the current research found that parent and child reports were more closely related than expected. For example, the obtained parent–child correlations were much higher than those reported in the literature generally (e.g., Kolko and Kazdin 1993; Hawley and Weisz 2003) and in meta-analytic research (Achenbach et al. 1987). At the same time, the obtained correlations are consistent with previous discrepancy research using the Ohio Scales (Carlston and Ogles 2006). These findings suggest that reducing item variability across measures appears to result in reduced discrepancy across reporters, although future research will necessarily need to continue to confirm these findings empirically.

Second, the average difference scores between parent and child were significantly different, yet relatively small (i.e., within the standard error of measurement). Given the magnitude of discrepancies it is important to replicate these findings to guard against over-interpretation of relatively little difference. On the other hand, while the average difference scores were relatively small, the item level differences were relatively large. In other words, even thought the actual total scores were similar, the symptom reports for individual items varied substantially. This finding is important as it highlights the importance of item level differences. Future research must take into consideration item level agreement.

Third, findings of the current research indicate that global parent and child reports of behavior and emotional experience are significantly, yet minimally, discrepant. Moreover, parents reporting a greater degree of overall symptomatology than their children. Furthermore, the degree and magnitude of said discrepancy is variable and approximately normally distributed. These findings are consistent with previously reported research using clinical samples (e.g., Kazdin et al. 1983; Thurber and Osborn 1992) and parallel previous findings regarding discrepancy in perceived presenting problem (Hawley and Weisz 2003; Yeh and Weisz 2001).

Findings of greater parental symptom reporting have been predicted by the Attribution Bias Context Model (ABC Model) proposed by De Los Reyes and Kazdin (2005). This model, the only current discrepancy model, suggests that attributional differences may account for reported symptom differences. In other words, parents are more likely, as observers, to attribute child behavior to the child’s disposition rather than environment. At the same time, children are more likely, as actors, to attribute symptoms to the environment. As a result, parents are more likely to report a greater number of child symptoms relative to their children. Similarly, parents are also more likely to see the child’s behavior as problematic whereas children do not. Applying this model to the current data would suggest that parental reports emphasize behavior as dispositional and problematic while child reports fail to endorse “problems” identified by others, as these behaviors represent shortcomings within the environment rather than within the child. Unfortunately, accuracy in prediction does not validate a model.

Concerns regarding the accuracy of the ABC Model further arise, as the model fails to explain the variations in discrepancy patterns. For example, differential patterns of discrepancy were observed across symptom domain (i.e., internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms). Consistent with model predictions, parents reported more externalizing symptoms than did their children. However, no significant differences between parent and child reports were obtained on reports of internalizing symptoms. Unfortunately, there are no provisions in the current model that explain or account for this differential findings across symptom domains. Other short-comings of the model are illustrated in following findings.

Fourth, this research also re-evaluates the impact of several important demographic variables on parent–child discrepancy: child age, gender, and ethnicity. Findings from the current study support previously reported findings that parent and child agreement is not influenced by child age (e.g., Achenbach et al. 1987; Yeh and Weisz 2001). When age categories are determined following developmental principles, there are no significant differences in discrepancy rates between younger and older children.

A relatively large body of literature exists evaluating the impact of gender on parent–child discrepancy. Findings from the current research indicate that the manner in which gender impacts discrepancy may vary as a function of the type of discrepancy analyzed. For example, parent–daughter discrepancies were significantly lower than parent–son discrepancies when comparing the mean differences of total problem severity and across both factor scores. However, parent–daughter discrepancies were significantly greater than parent–son discrepancies for both the total problem rating and the internalizing problem ratings when analyzing parent–child item differences. In other words, while parent and daughter total reports are relatively similar, their item level scores are more discrepant suggesting that parents and daughter are reporting different internalizing symptoms than their parents. On the other hand, parents and sons disagree in a systematic fashion with parents reporting slightly, yet consistently, greater severity ratings across all items than their sons.

Given the scarcity and limited nature of the existing research base evaluating the impact of child ethnicity on parent–child discrepancy, perhaps one of the most significant contributions made by the current research is the findings that self-reported ethnicity influences the degree of observed parent and child discrepancies. Specifically, the data demonstrated that Hispanic dyads demonstrated significantly less discrepancy than did African American and Caucasian families. This pattern held true in all analyses of difference scores and for the externalizing factor.

Findings from the current research have several implications for the field of discrepancy research. First, future research regarding reporter variability must use identical item measures of child behavior and functioning. Second, while a valuable beginning, it would appear that the ABC Model requires greater research investigation and significant elaboration and/or modification. For example, future revisions of the model will necessarily need to account for differential discrepancies across symptom domain. Specifically, future models must account for symptom awareness. Given the nature of internalizing symptoms, parents may be unaware of the frequency or even existence of their child’s internalizing symptoms (e.g., crying, thoughts of self-harm, hopelessness). Impaired ability to observe symptoms necessarily alters parental behavioral reports. Therefore, parental awareness of symptom manifestation is a predicating condition of all discrepancy models and must be incorporated as such.

Additionally, future theoretical models must necessarily account for discrepancy variations across demographic categories. For example, the current study indicates that child gender is a significant factor associated with parent–child discrepancies. One hypothesized explanation for gender influences on parent–child discrepancy is that boys and girls vary in the degree to which they are willing to disclose to their parents (Seiffge-Krenke and Kollmar 1998). If this were true, then discrepancy patterns across genders would consistently demonstrate greater parent–son discrepancy relative to parent–daughter discrepancy. However, the findings from the current study do not appear to support this interpretation. In the current study, greater item level parent–daughter discrepancy is observed on the internalizing factor while greater parent–son discrepancy is observed on the externalizing factor. Where disclosure the moderating factor, the item level discrepancy observed between daughters and parents would not have been observed. Therefore, it does not appear that disclosure is the primary cause for discrepancy variations across genders.

An alternate gender consideration is that boys may minimize the severity of their emotional experience more than girls. Previous research has demonstrated the existence of strong social pressures against male expression of traditional internalizing symptoms such as ruminations and worries (Li et al. 2006). Therefore, it is possible that the reason male reports of internalizing symptoms were more suppressed than female reports of similar symptoms in order to fill social expectations. Additionally, research has found that male youth are likely to minimize externalizing behaviors (Handwerk et al. 1999). Clearly, future research is needed to determine the mechanism by which gender influences observed discrepancies.

Lastly, the current research demonstrates that future models account for variations in observed discrepancies across ethnic groups. While several potential explanations are available for the differential patterns of discrepancy across ethnic groups observed in the current study, perhaps the most parsimonious explanation is that differences in agreement are related to culturally determined differences in family dynamics. In other words, aspects of the Hispanic family may produce greater agreement between parents and children. Specifically, Hispanic families have been found to be “more close” and evidence a stronger sense of familial unity than Caucasian families (Altarriba and Bauer 1998). As a result of this strong family cohesion, Hispanics are more inclined to seek advice and support from family members rather than third party professionals (Fuligni and Tseng 1999). It is highly probable that the strong family culture generates more communication regarding stressors and psychological symptoms which in turn leads to greater parent–child agreement on symptom severity.

The idea that family cohesion increases the degree of observed parent–child agreement is supported in other investigations regarding discrepancy. For example, Kolko and Kazdin (1993) collected a sample of 162 mothers and children from both community mental health centers and local school districts. In addition to evaluating the impact of several demographic factors on discrepancy, they evaluated the impact of family cohesion and family stress on parent–child agreement. They found that parents and children from less cohesive families and families under greater stress were associated with significantly greater parent–child discrepancies. Similarly, Andrews and colleagues (1993) also found that greater deficits in family cohesion were associated with greater parent–child discrepancy.

The cohesion–discrepancy relationship is also supported as African American parents consistently rated their child’s behavior as more severe than did the child. The observed discrepancies between African American parent and child reports can be explained using family cohesion. In contrast to Hispanic children and their parents, the generally poor family cohesion and the increased family stress associated with African American families (Lindsey and Cuellar 2000), would predict poorer parent–child discrepancy, as was observed.

While the family cohesion/stress explanations potentially accounts for ethnic differences in parent–child agreement, clearly the lack of data regarding actual family structure and dynamics in this study does not allow for conclusive statements. In fact, it is possible that obtained ethnic differences are merely an artifact of family functioning characteristics. Additional research will need to evaluate the impact of family functioning both within and across ethnic samples on reporter discrepancies.

Differential rates of discrepancies are an important area of future research, as discrepancy patterns across ethnic groups may have implications regarding service utilization and treatment compliance. Findings regarding differences in observed discrepancies across ethnic groups gain relevance when understood in terms of proposed models of barriers to treatment adherence (Kazdin et al. 1997). In their model, Kazdin and colleagues have identified four primary categories of barriers to treatment adherence: (1) experience of stressors and obstacles, (2) poor relationship with the therapist (including lack of perceived support and lack of disclosure), (3) perceptions of treatment irrelevance, and (4) perceptions of treatment as over-demanding. Discrepancy appears to be related to two of these categories. For example, discrepancy can influence client perceived support. As clinicians working with adolescents must balance parental and youth reports of problems and problem areas as the treatment plan is operationalized, therapists may subtly endorse one reporter’s perceptions over another. Apparent clinician favoritism can significantly reduce client perceived support and disrupt treatment.

In addition, perceived treatment irrelevance is also a bi-product of reporter discrepancies. When research indicates that approximately two thirds of parents and children fail to agree on a single presenting problem (Yeh and Weisz 2001), regardless of goals, the pursuit of treatment is likely to be seen as irrelevant to at least one shareholder. Although research regarding minorities in treatment has identified multiple risk factors that potentially moderate the negative relationship between service utilization, premature termination, and ethnic minority status (e.g., low SES, Reyno and McGrath 2006); therapeutic engagement, Hawke et al. 2005), this body of literature has failed to evaluate the impact of reporter discrepancies.

It is important to continue to evaluate the impact of ethnicity on treatment initiation and completion given the differential usage patterns. Furthermore, although efforts have been made to improve multicultural awareness in clinicians, the trend of minority under-utilization and premature termination continues to be reported (e.g., Austin and Wagner 2006; Diaz et al. 2005; King and Canada 2004; Shepherd et al. 2005; Staudt 2003). The current findings would suggest that discussion and evaluation of reporter differences may provide one more avenue of intervention designed to make psychological services more available to minority members.

Clearly, discrepancy research must be much more theoretical. More rigorous research must be conducted to evaluate the causes of discrepant reports. In other words, future research must focus on discrepancy process rather than discrepancy detection. Specifically, other process factors such as parental symptom awareness, family process, social gender perceptions must be incorporated into current theoretical models of discrepancy. Furthermore, while early discrepancy research using non-identical item measures has identified no significant gender effects in parent reporters (Achenbach et al. 1987; Handwerk et al. 1999; Stanger and Lewis 1993), it would be important that future research address parental gender using identical item measures, as the current research was unable to do so.

Most importantly, discrepancy research must address the question of clinical relevance. To do so, discrepancy research must be more applied in nature. In other words, future research will necessarily have to be cognizant of clinical relevance. For example, as the current research demonstrates, there is a considerable range of difference scores between parent and child reports. While overall differences were statistically significant, the observed mean differences were relatively small. In fact, nearly a third of parent–child difference scores did not exceed ten points, the cutoff for reliable change on the Ohio Scales. Therefore, future research may benefit from focusing on three separate groups of discrepant responders (i.e., child > parent, child = parent, child < parent) when evaluating both contributing factors and potential impact of discrepancies on therapy process (e.g., treatment planning, service provision, therapeutic alliance, satisfaction, symptom change). It is recommended that this research evaluate discrepancies using both d and d2 as they capture unique aspects of differential reports. Moreover, future research must be not only cognizant of ethnicity effects, but must actively engage the question of ethnicity and discrepancy as findings in these areas may help open access to treatment for a currently underserved population.

In summary, parent–child discrepancy on reports of problem behavior and emotional experience is a consistent phenomenon in the area of child assessment. This discrepancy is influenced by a number of factors. Discrepancy has both positive and negative implications for the therapeutic process from referral and diagnosis to treatment and outcome. As future research is able to account for the influence of universal factors on discrepancy and identify common characteristics associated with abnormal levels of discrepancy, variability across parent and child reports will become a clinical tool rather than a diagnostic confound.

References

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughty, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.213.

Altarriba, J., & Bauer, L. M. (1998). Counseling the Hispanic client: Cuban Americans, Maxican Americans, and Puerto Ricans. Journal of Counseling and Development, 76, 389–396.

Andrews, V. C., Garrison, C. Z., Jackson, K. L., Addy, C. L., & McKeown, R. E. (1993). Mother-adolescent agreement on the symptoms and diagnosis of adolescent depression and conduct disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 731–738.

Austin, A., & Wagner, E. (2006). Correlates of treatment retention among multi-ethnic youth with substance use problems: Initial examination of ethnic group differences. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 15(3), 105–128. doi:10.1300/J029v15n03_07.

Baize, H. (2001, October). Implications of the Oho Scales factor structure for scale utility and scoring. The Fourth Annual California Children’s System of Care Model Evaluation Conference, San Francisco.

Brookman-Frazee, L. (2005, March). Measuring outcome of usual care psychotherapy: Who and what to ask? In Garland, A. F. (Chair), The Complexities in measuring the impact of usual care youth psychotherapy. Symposium conducted at the 18th Annual “A System of Care for Children’s Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base” Research Conference.

California Department of Mental Health. (2000, October). Children and youth performance outcomes pilot study protocol and methodology summary. Retrieved July 22, 2007 from http://www.dmh.ca.gov/POQI/archive/docs/Child-Performance-Outcome-Pilot-Study-Protocols.pdf.

Carlston, D. L. (2005). Demographic and clinical factors associated with parent-child discrepancy from multiple statistical approaches. Doctoral dissertation, Ohio University, 2005. Dissertation Abstracts International, 65(9-B), 4819.

Carlston, D. L., & Ogles, B. M. (2006). The impact of items and anchors on parent-child reports of problem behavior. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 23(1), 24–37. doi:10.1007/s10560-005-0028-3.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 483–509. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483.

Diaz, E., Woods, S., & Rosenheck, R. (2005). Effects of ethnicity on psychotropic medication adherence. Community Mental Health Journal, 41, 521–537. doi:10.1007/s10597-005-6359-x.

Dowell, K. A., & Ogles, B. M. (in press). The Ohio scales youth form: Expansion and validation of a self-report outcome measure for young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies.

Epkins, C. C. (1996). Parent ratings of children’s depression, anxiety, and aggression: A cross-sample analysis of agreement and differences with child and teacher ratings. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 52, 599–608. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199611)52:6<599::AID-JCLP1>3.0.CO;2-G.

Fuligni, A. J., & Tseng, V. L. (1999). Attitudes towards family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development, 70, 1030–1044.

Handwerk, M. L., Lazelere, R. E., Soper, S. H., & Friman, P. C. (1999). Parent and child discrepancies in reporting severity of problem behavior in three out-of home settings. Psychological Assessment, 11, 14–23. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.11.1.14.

Hawke, J. M., Hennen, J., & Gallione, P. (2005). Correlates of therapeutic involvement among adolescents in residential drug treatment. Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 31, 163–177. doi:10.1081/ADA-200047913.

Hawley, K. M., & Weisz, J. R. (2003). Child, parent, and therapist (dis)agreement on target problems in outpatient therapy: The therapist’s dilemma and its applications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 62–70. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.62.

Kazdin, A. E., French, N. H., & Unis, A. S. (1983). Child mother and father evaluations in psychiatric in patient children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 11, 167–180. doi:10.1007/BF00912083.

Kazdin, A. E., Holland, L., & Crowley, M. (1997). Barriers to treatment participation scale: Evaluation and validation in the context of child outpatient treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38, 1051–1062. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01621.x.

King, A., & Canada, S. (2004). Client-related predicators of early treatment drop-out in a substance abuse clinic exclusively employing individual therapy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 26, 189–195. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00210-1.

Kolko, D. J., & Kazdin, A. E. (1993). Emotional/behavioral problems in clinic and nonclinic children: Correspondence among child, parent, and teacher reports. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34, 991–1006.

Li, C. E., DiGuiseppe, R., & Froh, J. (2006). The roles of sex, gender, and coping in adolescent depression. Adolescence, 41, 409–415.

Lindsey, M. L., & Cuellar, I. (2000). Mental health assessment and treatment of African Americans: A multicultural perspective. In I. Cuellar & F. A. Paniqua (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural mental health (pp. 195–208). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Offord, D. R., Boyle, M. H., Racine, Y., Szatmari, P., Fleming, J. E., Sanford, M., et al. (1996). Integrating assessment data from multiple informants. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1078–1085. doi:10.1097/00004583-199608000-00019.

Ogles, B. M., Dowell, K., Hatfield, D., Melendez, G., & Carlston, D. (2004). The Ohio Scales. In M. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 275–304). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Ogles, B. M., Melendez, G., Davis, D. C., & Lunnen, K. M. (1998). The Ohio youth problem, functioning, and satisfaction scales: Technical manual. Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Mental Health.

Ogles, B. M., Melendez, G., Davis, D. C., & Lunnen, K. M. (2001). The Ohio Scales: Practical outcome assessment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 10, 199–212. doi:10.1023/A:1016651508801.

Oman, R. F., McLeroy, K. R., Vesely, S., Aspy, C. B., Smith, D. W., & Penn, D. A. (2002). An adolescent age group approach to examining youth risk behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion, 16(3), 167–176.

Rey, J. M., Schrader, E., & Morris-Yates, A. (1992). Parent-child agreement on children’s behaviors reported by the child behavior checklist (CBCL). Journal of Adolescence, 15, 219–230. doi:10.1016/0140-1971(92)90026-2.

Reyno, S. M., & McGrath, P. J. (2006). Predictors of parent training effectiveness for child externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47, 99–111. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01544.x.

Rousseau, C., & Drapeau, A. (1998). Parent-child agreement on refugee children’s psychiatric symptoms: A transcultural perspective. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 629–636. doi:10.1097/00004583-199806000-00013.

Schaefer, B. A., Watkins, M. W., & Canivez, G. L. (1989). Cross-context agreement of the adjustment scales for children and adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 19, 123–136. doi:10.1177/073428290101900202.

Seiffge-Krenke, I., & Kollmar, F. (1998). Discrepancies between mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of sons’ and daughters’ problem behavior: A longitudinal analysis of parent-adolescent agreement on internalizing and externalizing problem behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 5, 687–697. doi:10.1017/S0021963098002492.

Shepherd, M., Ashworth, M., Evans, C., Robinson, S., Rendell, M., & Ward, S. (2005). What factors are associated with improvement after brief psychological interventions in primary care? Issues arising from using routine outcome measurement to inform clinical practice. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research, 5, 273–280. doi:10.1080/14733140600571326.

Stanger, C., & Lewis, M. (1993). Agreement among parents, teachers and children on internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Child Clinical Psychology, 22, 107–115. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2201_11.

Staudt, M. M. (2003). Helping children access and use services: A review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 12, 49–60. doi:10.1023/A:1021306125491.

Thompson, R. J., Merritt, K. A., Keith, B. R., Murphy, L. B., & Johndrow, D. A. (1993). Mother-child agreement on the Child Assessment Schedule with non-referred children: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 34, 813–820. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01073.x.

Thurber, S., & Osborn, R. A. (1992). Comparisons of parent and adolescent perspectives on deviance. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 154, 25–32.

Yeh, M., & Weisz, J. R. (2001). Why are we here at the clinic? Parent-child (dis)agreement on referral problems at outpatient treatment entry. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 1018–1025. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1018.

Youngstrom, E., Loeber, R., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2000). Patterns and correlates of agreement between parent, teacher, and male adolescent ratings of externalizing and internalizing problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 1038–1050. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1038.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carlston, D.L., Ogles, B.M. Age, Gender, and Ethnicity Effects on Parent–Child Discrepancy Using Identical Item Measures. J Child Fam Stud 18, 125–135 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-008-9213-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-008-9213-2