Abstract

There has been limited research examining the additive and interactive effects of multiple factors on the development of anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in youths. This study was an attempt to examine the reciprocal connections among temperament, attachment, and rearing style, and their unique and interactive relations to anxiety symptoms. Six hundred forty-four non-clinical children aged 11–15 years (mean age = 12.7 years) completed questionnaires measuring behavioral inhibition, attachment, parental rearing behavior, and anxiety symptoms. Results indicated that there were small to moderate positive correlations among various risk factors. Furthermore, modest but significant positive correlations were found between behavioral inhibition, attachment quality, and anxious and controlling rearing behaviors on the one hand, and anxiety scores on the other hand. That is, higher levels of behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, and parental control and anxious rearing were associated with higher levels of anxiety symptoms. Finally, behavioral inhibition, attachment quality, parental control and anxious rearing each accounted for a small but unique proportion of the variance of anxiety disorders symptomatology. Little support was found for interactive effects of these vulnerability factors on childhood anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent psychiatric problems in children and adolescents (Bernstein, Borchardt, & Perwien, 1996; Craske, 1997). A review of 16 epidemiological studies (1988–1995) shows estimates for the presence of any anxiety disorder ranges from 5.7% to 17.7%, with half of them exceeding the 10% rate (Costello & Angold, 1995). The interest in research on anxiety disorders in children has grown enormously during the past two decades (Muris, 2006). A number of these studies have been devoted to its etiology and are thus concerned with the question of which factors contribute to the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents.

One dispositional variable that is thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of anxiety disorders is behavioral inhibition. Children who are characterized by a behaviorally inhibited temperament tend to display fear and withdrawal in situations that are novel or unfamiliar (Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1988). Research has shown that these children seem to be at risk for developing anxiety disorders. Findings of Biederman et al. (1990) indicate that inhibited children, compared to uninhibited children, more frequently displayed the clinical symptoms of multiple anxiety disorders. Moreover, in a longitudinal study, Biederman, Rosenbaum, Bolduc-Murphy, and Faraone (1993) found that pre-school children initially identified as behaviorally inhibited were more likely to have developed anxiety disorders at 3-years follow-up compared to control children (i.e., children who at study onset were not classified as behaviorally inhibited). Further support for a link between behavioral inhibition and anxiety comes from a series of studies conducted by Muris and colleagues (1999, 2001b, 2003a). In these studies, adolescents and their parents completed a questionnaire measuring children's behaviorally inhibited temperament. Results showed that children who were identified as high on behavioral inhibition displayed higher levels of anxiety compared to children who were classified as low on behavioral inhibition. All the above-mentioned studies suggest that behavioral inhibition is associated with the development of a broad range of anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders.

Besides temperament, attachment theory provides an explanation for the development of anxiety disorders in children. For example, in their longitudinal study, Warren et al. (1997) found a specific link between insecure (in particular, ambivalent) attachment assessed in infancy and anxiety disorders assessed some 16 years later. A study by Mannasis, Bradley, Goldberg, Hood, and Swinson (1994) examining attachment in mothers with anxiety disorders and their children, showed that all children with diagnosed anxiety disorders were insecurely attached. Results of another study by this research group demonstrated that insecurely attached children had higher levels of internalizing problems than their securely attached counterparts (Mannasis, Bradley, Goldberg, Hood, & Swinson, 1995). In three subsequent studies, Muris and colleagues (Muris, Mayer, & Meesters, 2000a; Muris, Meesters, Merckelbach, & Hülsenbeck, 2000b; Muris, Meesters, van Melick, & Zwambag, 2001a) found that adolescents who defined themselves as insecurely attached displayed higher levels of anxiety and worry than youths who defined themselves as securely attached.

Another factor that seems to play a role in the origins of anxiety is parental rearing behavior. Two parenting dimensions that have been repeatedly associated with the development of anxiety in children and adolescents are control and anxious rearing (e.g., Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang, & Chu, 2003). Control can be best described as parental behaviors aimed at guiding the child during daily activities. These parental behaviors often have the effect of directing the child and reducing the development of autonomy (Rapee, 1997). Anxious rearing pertains to the explicit encouragement of anxious cognitions and avoidance behaviors in children (e.g., Barrett, Rapee, Dadds, & Ryan, 1996; Grüner, Muris, & Merckelbach, 1999). Several studies have found confirming evidence for the proposed relationship between controlling rearing behaviors and anxiety disorder symptoms, some of them relying on direct observation of parent-child interactions (Hudson & Rapee, 2001; Whaley, Pinto, & Sigman, 1999) and others making use of questionnaires that intend to measure children's perceptions of parental rearing behaviours (Grüner et al., 1999; Muris et al., 2000b; Muris, Meesters, & van Brakel, 2003b).

Vasey and Dadds (2001) described an integrative framework for conceptualizing the various pathways associated with the development of childhood anxiety disorders. The core issue in this model is the dynamic interplay of various potential predisposing factors in the pathogenesis of anxiety. Studies examining additive and interactive effects of these factors on childhood anxiety are just beginning to emerge. For example, Calkins and Fox (1992) obtained evidence for a reciprocal relation between attachment style and behavioral inhibition. That is, in their sample of young infants, insecure attachment appeared to promote behavioral inhibition, whereas behavioral inhibition seemed to hinder the formation of a secure attachment relationship, thereby further enhancing children's vulnerability to anxiety. Mannasis et al. (1995) found that within a group of inhibited children, the children with an insecure attachment showed higher levels of anxiety symptoms in comparison to the children with a secure attachment. Muris et al. (2000b) found that adverse parental rearing and insecure attachment in primary school children were both positively linked to symptoms of worry. Moreover, the results of this study showed that there were significant associations between parental rearing and attachment style and that both factors accounted for independent variance in worry scores. The results of a similar study in young, non-clinical adolescents (Muris & Meesters, 2002) indicate that attachment and behavioral inhibition both play a unique role in the manifestation of childhood anxiety.

Altogether, there has been limited research examining the additive and interactive effects of multiple risk factors on the development of anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in youths. This study was an attempt to examine the reciprocal relations among inhibited temperament, insecure attachment, and anxious and controlling rearing behaviors, and their contribution to anxiety. It was hypothesized that behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, and a controlling or anxious rearing style independently predict adolescents’ anxiety symptoms. Moreover, we examined the interactive effects of these risk factors on children's anxiety symptoms.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were 644 children (337 boys and 307 girls) recruited from regular secondary schools in The Netherlands. The mean age of the sample was 12.73 years (SD=.54, range 11–15 years). Children were primarily Caucasian (>90%). Due to school constraints, information about the socioeconomic status and family structure of the children was not available. All children completed the questionnaires in their classrooms with the teacher and a research assistant always present to ensure independent and confidential responding and to provide assistance if necessary. Children and parents were informed about the aim and content of the study. None of the participants refused to participate, yielding a response rate of 100%.

Questionnaires

Inspired by the work of Gest (1997), Muris et al. (1999) developed the Behavioral Inhibition Scale (BIS), a brief self-report questionnaire for assessing behavioral inhibition. The BIS consists of 4 items referring to shyness, communication, fearfulness, and smiling (e.g., “I feel nervous when I have to talk to an unfamiliar person”). Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale: 1 means never, 2 sometimes, 3 often, and 4 always. After recoding the positive items, scores are summed to yield a total BIS score, ranging from 4 (not apprehensive, not shy and very sociable when meeting an unfamiliar person) to 16 (very apprehensive and shy and not capable of initiating social interaction with an unfamiliar person).

Previous research has yielded support for the reliability and validity of the BIS. To begin with, in a recent study by Van Brakel, Muris, and Bögels (2004), the relation between the BIS and observable manifestations of behavioral inhibition was examined. Moderate but significant relations were found between parent- and teacher-reported behavioral inhibition of the child as measured by the BIS and the observational index of this temperamental trait, thus providing evidence for the validity of the scale. Further, an investigation by Muris et al. (2003a) showed that self-report BIS scores had acceptable correlations with parent ratings on the BIS. Finally, the reliability of the BIS appears good, with Cronbach's alphas well above .80 and a test-retest correlation of .77 over a 2-year period (see Van Brakel & Muris, 2006).

The Attachment Questionnaire for Children (AQ-C) consists of three descriptions concerning children's feelings about and perceptions of their relationships with other children: (1) “I find it easy to become close friends with other children. I trust them and I am comfortable depending on them. I do not worry about being abandoned or about another child getting too close friends with me.” (secure attachment); (2) “I am uncomfortable to be close friends with other children. I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to depend on them. I get nervous when another child wants to become close friends with me. Friends often come more close to me than I want them to.” (avoidant attachment); and (3) “I often find that other children do not want to get as close as I would like them to be. I am often worried that my best friend doesn't really like me and wants to end our friendship. I prefer to do everything together with my best friend. However, this desire sometimes scares other children away.” (ambivalent attachment).

Children are provided with these descriptions and instructed to choose the description that applies best to them. In this way, they classify themselves as either securely, avoidantly, or ambivalently attached.

In this study, the AQ-C was dichotomized after the children had chosen one of the three descriptions. That is, secure attachment was recoded as 0, whereas avoidant and ambivalent attachment were both recoded as 1. In a study by Muris et al. (2001a), the connection between the AQ-C and a concurrent measure of attachment, the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), was examined. Results showed that adolescents who classified themselves as securely attached on the AQ-C displayed a higher quality of attachment to both parents and peers than adolescents who classified themselves as insecurely (i.e., avoidantly or ambivalently) attached on the AQ-C. Clearly, this finding supports the validity of the AQ-C.

Modified EMBU-C (Child version of the Egna Minnen Beträffende Uppfostran, which is Swedish for My memories of upbringing; Castro, Toro, Van Der Ende, & Arrindell, 1993; Muris, Bosma, Meesters, & Schouten, 1998). The EMBU-C originally was a 41-item questionnaire measuring four types of parental rearing: emotional warmth, rejection, control, and favoring subject. Grüner et al. (1999) modified the EMBU-C in three ways. First, new items were added in an attempt to measure children's perceptions of their parents’ anxious rearing behaviors. Second, all items referring to children's brothers and sisters (i.e., the favoring subject subscale and two additional items) were removed because not all children have brothers and sisters. Third, for each type of parental rearing, the number of items was reduced to 10.

The modified EMBU-C consists of 40 items that can be allocated to four types of parental rearing: emotional warmth, rejection, control, and anxious rearing. For each EMBU-C item, children first assess father's rearing behavior and then mother's rearing behavior, using 4-point Likert-scales (1=No, never, 2=Yes, but seldom, 3=Yes, often, 4=Yes, most of the time). The psychometrics of the modified EMBU-C were tested in a large sample of children and adolescents (N=1702). Results showed that the scale has a clear-cut 4-factor structure, which is in correspondence with the hypothesized subscales. Furthermore EMBU-C scales were reliable in terms of internal consistency and test-retest stability (Muris et al., 2003b). In the current study only two EMBU-C subscales were used, control (e.g., “When you come home, you have to tell your parents what you have been doing”) and anxious rearing (e.g., “Your parents are scared when you do something on your own”), as these seem most relevant in relation to anxiety symptoms (Muris et al., 2003b).

The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) is a 41-item self-report questionnaire for measuring symptoms of panic, social phobia, separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, and school phobia (Birmaher et al., 1999). Children have to indicate how frequently they experience each symptom (e.g., “I worry about things working out for me,” “When I am frightened, my heart beats fast”) on a 3-point scale: 0 = almost never, 1 = sometimes, and 2 = often. In the present study, the SCARED total anxiety score was used, which can be obtained by summing across relevant items. Analyses examining main and interactive effects of various vulnerability factors on SCARED anxiety subscales generally yielded comparable results. That is, in most equations, significant main effects of behavioral inhibition, attachment, and/or parental rearing were found, whereas interactive effects were generally weak and non-significant. Total percentages of explained variance varied between 10.0% (school phobia) and 57.3% (social phobia). Previous research has demonstrated that the SCARED has good internal consistency (e.g., Birmaher et al., 1997; Muris, Schmidt, & Merckelbach, 2000c), test-retest reliability, and discriminant validity (e.g., Birmaher et al., 1997, 1999).

Results

General findings

Before addressing the main research questions of our study, some general remarks should be made. First, all questionnaires were reliable in terms of internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha being .77 for the BIS, .65 for EMBU-C control, .77 for EMBU-C anxious rearing, and .91 for the SCARED. Second, t-tests revealed that girls scored significantly higher than boys on anxiety symptoms (SCARED) [t(641)=5.34, p < .001] and behavioral inhibition (BIS) [t(642)=3.23, p < .01]. Moreover, girls rated themselves more often as being insecure attached than boys [χ 2(1)=5.07, p < .05]. Thus, girls were found to be generally more distressed than boys, which is in keeping with what has been reported in the literature (e.g., Craske, 1997). Third, no significant associations between age and any of the measures emerged. Fourth, as rearing behaviors of mothers and fathers were significantly related to each other [rs were .72, p < .001 for control and .76, p < .001 for anxious rearing], scores of mother and father were summed, and these total control and anxious rearing scores were used in further analyses.

Correlations among risk factors

There were small to modest but significant intercorrelations among various risk factors (Table 1). More specifically, behavioral inhibition correlated .32 with insecure attachment, .11 with control, and .14 with anxious rearing. Insecure attachment correlated .14 and .10 with respectively control and anxious rearing, whereas a correlation of .52 was found between both types of rearing behaviors. Altogether, these findings indicate that although these risk factors share some common variance, they seem to represent a set of relatively independent constructs.

Relationship with anxiety symptoms

Table 1 also shows Pearson correlations between behavioral inhibition, attachment, and rearing behaviors, on the one hand, and anxiety symptoms, on the other hand. Results indicated that there were modest but significant positive correlations between behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, control, and anxious rearing, on the one hand, and anxiety scores on the other hand. That is, higher levels of behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, parental control and anxious rearing were associated with higher levels of anxiety symptoms. As girls displayed higher levels of anxiety symptoms and behavioral inhibition, and were more frequently insecurely attached than boys, correlations were also computed for boys and girls separately. For both genders, results were highly similar as those obtained for the total group.

Additive and interactive effects of risk factors on anxiety

Stepwise hierarchical regression analyses were carried out in order to examine the additive and interactive effects of various risk factors to adolescents’ anxiety symptoms. In these analyses, scores on BIS, AQ-C, and EMBU-C were the predictor variables, whereas the total score on the SCARED served as the dependent variable. The following strategy was used for entering various predictor variables. On the first two steps, the main effects of the child factors of insecure attachment and behavioral inhibition, and their interaction were examined. The following step included the environmental factor of parental rearing, and the final steps investigated interaction effects of child and environmental factors.

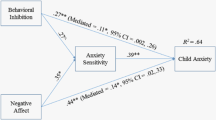

Table 2 shows the main results of the regression analysis with behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, and parental control being the predictors and anxiety disorder symptoms as the dependent variable. The results indicate that behavioral inhibition (β=.43; p < .001), insecure attachment (β=.26; p < .001), and control (β=.13; p < .001) each accounted for a small but unique proportion of the variance, which indicates that all these factors had additive predictive value for adolescents’ anxiety.

Two significant interaction effects were found. To begin with, behavioral inhibition and insecure attachment had an interactive effect on anxiety (β=.09, p < .05). Although this effect was small (as it accounted for less than 1% of the variance), the pattern of results was as expected: that is, children who defined themselves as high on behavioral inhibition and insecurely attached displayed the highest levels of anxiety symptoms, whereas children who classified themselves as low on inhibition and securely attached exhibited the lowest levels of anxiety symptoms. Further, a higher-order effect was found for the interaction between behavioral inhibition, attachment quality, and control (β=.12; p < .01). Figure 1 visualizes this higher-order interaction. As expected, children who define themselves as high on behavioral inhibition and insecurely attached showed higher levels of anxiety symptoms. The role of parental control, however, was less consistent. In some children (i.e., uninhibited/securely attached and inhibited/insecurely attached), high levels of this rearing factor were associated with higher anxiety levels, whereas in other children (i.e., inhibited/securely attached) high control was related to lower anxiety levels.

Table 3 shows the main results of the regression analysis with behavioral inhibition, attachment quality, and anxious rearing as predictors and anxiety disorder symptoms being the dependent variable. The results indicate that behavioral inhibition (β=.43; p < .001), insecure attachment (β=.26; p < .001), and anxious rearing (β=.22; p < .001) each accounted for a small but unique proportion of the variance. Besides the significant interaction of behavioral inhibition and attachment (see supra), no interaction effects were found.

Separate analyses for boys and girls essentially yielded similar results. In all analyses, significant main effects of behavioral inhibition, attachment, and parental rearing were found (all betas between .14 and .48, all ps < .01). The interaction effects that were found when analysing the total sample disappeared, which underlines that these effects were not very robust.

Discussion

Our study was a first attempt to examine the reciprocal connections among temperament, attachment, and parental rearing style, and their additive and interactive contributions to anxiety symptoms. The main results of the study can be presented as follows. First, there were small to modest positive correlations among behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, and the hypothesized anxiety-promoting rearing behaviors of control and anxious rearing, indicating that these child and environmental risk factors were to some extent related to each other. Second, behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, and parental control and anxious rearing were positively associated with higher levels of anxiety symptoms. Finally, behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, and parental rearing each accounted for a unique proportion in the variance of anxiety disorders symptoms.

The results of this study seem to indicate that behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, and parental rearing predominantly have additive effects on the development of anxiety. Few interaction effects among these vulnerability factors were found and it should be emphasized that such effects were rather small. For example, the interaction effect of attachment and behavioral inhibition was theoretically meaningful (with the combination of insecure attachment and high levels of inhibition yielding the highest anxiety scores), but accounted for less than 1% of the variance.

The higher-order interaction effect of behavioral inhibition, insecure attachment, and control on anxiety symptoms was somewhat larger. This effect was due to the fact that, in some children (i.e., uninhibited/securely attached and inhibited/insecurely attached), high levels of this rearing factor were associated with higher anxiety levels, whereas in other children (i.e., inhibited/securely attached), high control was related to lower anxiety levels. These divergent effects of parental control on anxiety can be explained when one adopts the notion that this rearing factor has multiple faces. On the one hand, control may be associated with extreme strictness, which has the negative consequence of reducing the development of autonomy. On the other hand, control has the positive consequence of structuring the child's environment. When looking at our data, it can be suggested that on the condition that inhibited children have parents who are sensitive and responsive (in such a way that caregiver and child are securely attached), a highly controlling parenting style has a positive influence on the anxiety symptoms of these children. That is, in this group of children, highly controlling parents offer just the structure these children need to help them navigate through their daily lives, and hence reduce anxiety. However, when children do not need such assistance (i.e., the uninhibited/secure group) or when children do need guidance but their parents cannot provide it (i.e., the inhibited/insecure group), control may manifest itself in its negative overprotective way and thus enhance anxiety.

It should be acknowledged that our study suffers from several shortcomings. First, the study solely relied on adolescents’ self-report. Inclusion of parent versions of various questionnaires would have provided important cross-validational information on the role of behavioral inhibition, attachment, and rearing behaviors in the development of childhood anxiety. For example, we know that children who are significantly anxious often have cognitive distortions that may contribute to perceiving others (e.g., parents) in an overly threatening/negative way. For this reason, multiple informants or observational measures should be used in future studies. Second, the participants in this study were still relatively young. As it is clear that some anxiety symptoms (i.e., social phobia, generalized anxiety, panic disorder) become more clearly manifest in middle or late adolescence (e.g., Costello & Angold, 1995), it remains unclear to what extent the results can be generalized to older children. A third shortcoming has to do with the scales that were employed to measure attachment. Previous research has shown that children of this age have a tendency to endorse the positively toned, secure attachment item rather than the more negatively toned descriptions of avoidant and ambivalent attachment. Thus, reliance on the AQ-C to assess children and adolescents’ attachment style may lead to an underreporting of insecure attachment types (Muris et al., 2000a, 2001a). Clearly, a study examining the link between self-reported attachment and observational and narrative measures of this construct could clarify this issue. In a similar vein, one could question the validity of the BIS and simply qualify it as a measure of social anxiety. Note, however, that the BIS was developed closely following the definition of this temperamental construct (see Gest, 1997) and previous research has demonstrated that the overlap with social anxiety is at best modest (Van Brakel et al., 2004).

A final point of critique pertains to the fact that we only assessed a restricted number of risk factors. For example, one important vulnerability factor that was not included is parental anxiety. Many findings support the notion that relationships between anxious parents and their children are characterized by different factors than those between normal parents and their children (Turner, Beidel, Roberson-Nay, & Tervo, 2003). Thus, data on parental anxiety would have enabled us to differentiate between children with a family history of anxiety and those without such history. In this way, we could have mapped the differences of these families with respect to attachment relationships, behavioral inhibition, and parental rearing behaviors.

Despite these limitations, the current data provide further support for the notion that various potential predisposing factors have additive and, to some extent, interactive effects on anxiety. Of course, longitudinal studies, preferably including clinically referred youths, are needed to shed light on the direction of relations between behavioral inhibition, attachment, parental rearing behavior, and other risk and protective factors on the one hand, and childhood anxiety problems on the other hand.

References

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence, 16, 427–454.

Barrett, P., Rapee, R., Dadds, M. R., & Ryan, S. M. (1996). Family enhancement of cognitive style in anxious and aggressive children: Threat bias and the FEAR effect. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 187–203.

Bernstein, G. A., Borchardt, C. M., & Perwien, A. R. (1996). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1110–1119.

Biederman, J., Rosenbaum, J. F., Bolduc-Murphy, E. A., & Faraone, S. V. (1993). A three year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 814–821.

Biederman, J., Rosenbaum, J. F., Hirshfeld, D. R., Faraone, S. V., Bolduc, E. A., Gersten, M., Meminger, S. R., Kagan, J., Snidman, N., & Reznick, J. S. (1990). Psychiatric correlates of behavioral inhibition in young children of parents with and without psychiatric disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47, 21–26.

Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Chiappetta, L., Bridge, J., Monga, S., & Baugher, M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1230–1236.

Birmaher, B., Khetarpal, S., Brent, D., Cully, M., Balach, L., Kaufman, J., et al. (1997). The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 545–553.

Calkins, S., & Fox, N. (1992). The relations among infant temperament, security of attachment, and behavioral inhibition at twenty-four months. Child Development, 63, 1456–1472.

Castro, J., Toro, J., Van Der Ende, J., & Arrindell, W. A. (1993). Exploring the feasibility of assessing perceived parental rearing styles in Spanish children with the EMBU. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 39, 47–57.

Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (1995). Epidemiology. In J. S. March (Ed.), Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (pp. 109–124). New York: Guilford Press.

Craske, M. G. (1997). Fear and anxiety in children and adolescents. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 61(suppl. A), A4–A36.

Gest, S. D. (1997). Behavioral inhibition: Stability and associations with adaptation from childhood to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 467–475.

Grüner, K., Muris, P., & Merckelbach, H. (1999). The relationship between anxious rearing behaviours and anxiety disorders symptomatology in normal children. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 30, 27–35.

Hudson, J. L., & Rapee, R. M. (2001). Parent-child interactions and anxiety disorders: An observational study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 1411–1427.

Kagan, J., Reznick, J. S., & Snidman, N. (1988). Biological bases of childhood shyness. Science, 240, 167–171.

Mannasis, K., Bradley, S., Goldber, S., Hood, J., & Swinson, R. P. (1994). Attachment in mothers with anxiety disorders and their children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 1106–1113.

Mannasis, K., Bradley, S., Goldberg, S., Hood, J., & Swinson, R. P. (1995). Behavioural inhibition, attachment and anxiety in children of mothers with anxiety disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 40, 87–92.

Muris, P. (2006). The pathogenesis of childhood anxiety disorders: Considerations from a developmental psychopathology perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 5–11.

Muris, P., Bosma, H., Meesters, C., & Schouten, E. (1998). Perceived parental rearing behaviours: A confirmatory factor analytic study of the Dutch EMBU for children. Personality and Individual Differences, 24, 439–442.

Muris, P., Mayer, B., & Meesters, C. (2000a). Self-reported attachment style, anxiety, and depression in children. Social Behavior and Personality, 28, 157–162.

Muris, P., & Meesters, C. (2002). Attachment, behavioral inhibition, and anxiety disorders symptoms in normal adolescents. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 24, 97–105.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., Merckelbach, H., & Hülsenbeck, P. (2000b). Worry in children is related to perceived parental rearing and attachment. Behavior Research and Therapy, 38, 487–497.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Spinder, M. (2003a). Relationships between child- and parent-reported behavioural inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression in normal adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 759–771.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & van Brakel, A. (2003b). Assessment of anxious Rearing Behaviors with a modified version of “Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran” questionnaire for children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 25, 229–237.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., van Melick, M., & Zwambag, L. (2001a). Self-reported attachment style, attachment quality, and symptoms of anxiety and depression in young adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 809–818.

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Schmidt, H., Gadet, B., & Bogie, N. (2001b). Anxiety and depression as correlates of self-reported behavioural inhibition in normal children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 1051–1061.

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Wessel, I., & Ven de van, M. (1999). Psychopathological correlates of self-reported behavioural inhibition in normal children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 575–584.

Muris, P., Schmidt, H., & Merckelbach, H. (2000c). Correlations among two self-report questionnaires for measuring DSM-defined anxiety disorder symptoms in children: The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders and the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 333–346.

Rapee, R. M. (1997). Potential role of childrearing practices in the development of anxiety and depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 47–67.

Turner, S. M., Beidel, D. C., Roberson-Nay, R., & Tervo, K. (2003). Parenting behaviors in parents with anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41, 541–555.

Van Brakel, A. M. L., Muris, P., & Bögels, S. M. (2001). Gedragsinhibitie als risicofactor voor het ontwikkelen van angststoornissen bij kinderen: Een overzicht.(Behavioral inhibition as a risk factor for the development of anxiety disorders in children:a review). Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Psychologie en haar grensgebieden, 56, 57–68.

Van Brakel, A., & Muris, P. (2006). A brief scale for measuring “behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar” in children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 28, 79–84.

Van Brakel, A. M. L., Muris, P., & Bögels, S. M. (2004). Relations between parent- and teacher-reported behavioral inhibition and behavioral observations of this temperamental trait. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 579–589.

Vasey, M. W., & Dadds, M. R. (2001). An introduction to the developmental psychopathology of anxiety. In M. W. Vasey & M. R. Dadds (Eds.), The developmental psychopathology of anxiety (pp. 3–26). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Warren, S. L., Huston, L., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (1997). Child and adolescent anxiety disorders and early attachment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 637–644.

Whaley, S. E., Pinto, A., & Sigman, M. (1999). Characterizing interactions between anxious mothers and their children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 826–836.

Wood, J. J., McLeod, B. D., Sigman, M., Hwang, W-C., & Chu, B. C. (2003). Parenting and childhood anxiety: Theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 134–151.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Brakel, A.M.L., Muris, P., Bögels, S.M. et al. A Multifactorial Model for the Etiology of Anxiety in Non-Clinical Adolescents: Main and Interactive Effects of Behavioral Inhibition, Attachment and Parental Rearing. J Child Fam Stud 15, 568–578 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9061-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9061-x