Abstract

This study, based on data collected in 2005 from Chai Nat province, examines the level of happiness of the Thai elderly population and its relationship to various external and internal factors. It was found that mean happiness was slightly above a feeling of "neutral." According to multiple regression analyses, external factors including economic hardship, living arrangements, functional ability, perceived social environment, and consumerism significantly influence the level of happiness. The strongest predictor of happiness is, however, the internal factor—that is, a feeling of relative poverty when compared to their neighbors. Controlling for demographic and all external factors, the respondents who do not feel poor show the highest level of happiness compared to those who feel as poor as or poorer than their neighbors. This is self-interpreted as a feeling of contentment with what one has, which has been influenced by Thai culture, which is pervaded by Buddhism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The fact that economic and social well-being influences happiness among older persons has long been recognized by researchers in several social sciences, including economics. Economic hardship has been found to be an important source of feelings of depression among the elderly in both the West and in Asia (George 1992; Knesebeck et al. 2003; Li 1995). Recent research finds that a certain level of economic well-being would seem to be a necessary condition of happiness, but after people reach a certain level of income, more money does not lead to greater happiness (Inglehart and Klingemannh 2000). Similarly, it has been found that increased income and possession of more and more material goods have little impact on the feeling of well-being. Rather, happiness tends to be associated with friendships and family life once people rise above the poverty level (Lane 2000).

Not only do the external factors mentioned above influence happiness, but so do internal factors. According to Phra Phaisan VisaloFootnote 1, a Thai Buddhist monk, happiness depends on the level of security in the human mind (Visalo 1998). A feeling of security can come from two major sources. The first is through external factors, such as economic status, health status, social environment, and family situation. The second is through internal factors such as the peace of mind that can occur by having religious faith and trust. In addition, accustoming the mind to coping with the stress generated from certain life-events and trying to maintain a positive attitude towards life can greatly influence one's feeling of security or well-being (Alexandrova 2005). Empirically, the external factors noted above have been well established as predictors of happiness among older persons in most research carried out in both the West and Asia (Herzog and Rodgers 1981; Krause et al. 1998; Meng and Xiang 1997; Pei and Pillai 1999; Pinquart and Sorensen 2000), but the internal factors have not.

Thailand presents an interesting setting in which to examine this issue. The predominance of Theravada Buddhism is considered an important aspect of the Thai setting since it influences Thai people's attitudes, thoughts, and way of life (Knodel et al. 1987). Buddhism teaches that avoiding the two extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification leads to vision, knowledge, awakening, and “nirvana”—i. e., the release from suffering caused by anger and delusion, which is the ultimate goal of Buddhists (Bhikkhu 1996; Doniger 1999). According to Buddhadasa BhikkhuFootnote 2, the ultimate Buddhist goal is true happiness, that is, a spiritual happiness characterized by a freedom from craving (2005). It is different from the happiness of lay people that is typically used in happiness studies in modern social science. This latter happiness depends on success in gratifying one's desires.

Inspired by Buddhism, Thai lay people tend to subscribe to the Buddhist notion of seeking a path of moderation between two extremes, feeling satisfied with what they have and not feeling that resources are never sufficient to meet increasing desires. Efforts of the Thai government to stimulate economic growth in their development strategies by deepening capitalism and incorporating more of the nation's people and resources into the market economy, which have been employed since 2001 (Phongpaichit and Baker 2004), may have influenced this phenomenon of increasing desires. The situation in Thailand thus provides a good opportunity to study the importance of both external and internal factors on the level of happiness among the Thai elderly.

The two main research questions of this study are: (1) To what extent are the Thai elderly satisfied with their lives? and (2) What are the major determinants of their feeling of happiness? We focus on both external and internal factors.

Determinants of happiness

Happiness and life satisfaction are subjective measurements of well-being. Subjective well-being is typically referred to as a person's evaluative reactions to his or her life either in terms of life satisfaction (cognitive evaluations) or affect (ongoing emotional reactions) and as satisfaction with life as a whole (Diener and Diener 1995). The concepts of life satisfaction and happiness are interrelated, but are not exactly the same. The former is seen more as the outcome of an evaluation process, while the latter as an outcome of positive experiences (Alexandrova 2005; Max and Markus 2006). Despite this difference, some researchers, notably from sociology and economics, tend to see happiness, subjective well-being, and life satisfaction as synonymous and interchangeable (Heylighen 1992; Veenhoven 1991, 1997; Easterlin 2001, 2005; Kohler et al. 2005; Chan and Lee 2006). Additionally, the predictors or components of happiness, life satisfaction, or subjective well-being tend to overlap whenever the term is used. Thus, as a practical matter, the term used should not matter very much when determinants are the focus of study.

Most of the research on happiness, life satisfaction, or subjective well-being of the elderly both in the West and in Asia has focused on the same predictors, such as health, socioeconomic status (SES), and social supports although specific indicators vary from study to study. Some studies have used financial difficulties, health problems, and loneliness as major determinants of life satisfaction of older persons (Silverman et al. 2000; Li 1995). In some studies, such as those carried out in urban China, income or financial strain is the most important factor leading to depression among the elderly (Li 1995; Liu et al. 1995). However, in other studies, personal network size and perceived social support is found to be more important than income in determining happiness (Chan and Lee 2006). Perceived available social support generally reflects an individual's feeling that he/she is accepted, loved, and valued by other members of the social network.

In many Asian countries, where the traditional pattern of elderly living with children or other extended family members is pronounced, variables other than economic conditions, such as family variables, are found to be significantly related to the perception of happiness among aged people. Such variables include, for example, the number of relatives, family size, and living arrangements (Ho et al. 1995; Meng and Xiang 1997; Pei and Pillai 1999).

Moreover, psychological well-being is measured differently in the East and in the West. Ryff, for example, found that psychological well-being in the West is predominantly intrapersonal and is characterized by self-acceptance, autonomy, and personal growth (Ryff 1989). In Thailand, on the other hand, well-being is found to be related to both intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Ingersoll-Dayton et al. (2004) have found that psychological well-being of Thai elderly consists of five components: (1) harmonious relationships within one's family and with neighbors; (2) reliability in the provision of assistance among themselves, children and relatives, neighbors, and communities; (3) having a peaceful mind (coaxing the mind to be happy) and being accepted by others; (4) being respected; and (5) having activities with friends and going to temples.

However, there is some similarity in terms of an intrapersonal factor between East and West. According to Buddhism, a religion that is predominant in the East, cultivation of one's mind to be able to cope with increasing desire is a way for lay people to achieve happiness (Bhikkhu 2005). Even an economist from the West argues that the ability to control one's mood or spirit is a predictor of happiness. On the other hand, social comparison, particularly with regard to relative income, makes it more difficult to control one's mood (Layard 2005). Thus, those who dwell on the fact that they are poorer than the others and lose control of their moods are likely to fall into deep depression. However, this kind of internal factor has not yet been tested as a predictor of happiness in previous studies.

Material and Methods

Our study is based on a research project of Mahidol University using a community participatory approach for poverty eradication in Thailand. One of the objectives of this project was to develop indicators of the population's well-being. To serve this purpose, a survey was carried out using face-to-face interviews in Chai Nat province in August 2005. Stratified two-stage sampling designed by the National Statistical Office was adopted. This survey included private households only. The sampling was crafted to collect data representative of the entire province, which includes 1,440 sample households; 2,984 persons aged 15 and over in the sample households were interviewed. The population aged 55 years and older were selected for this study.

One noteworthy feature of the survey is that, if the person targeted for an interview was unavailable, another person in the household was interviewed as a proxy. The exception was, however, for the questions on happiness, for which a proxy was not allowed. Interviews were conducted with about 90.4% of the population aged 55 and over. The total sample included 1,036 persons. We found that the level of happiness reported was either positively or negatively extreme among those respondents over age 80. Therefore, only persons aged 55–80 were included in our analyses. Thus, the final sample size was 986. All respondents in the sample were Buddhists. In this paper, the results are all weighted.

Setting

With a decline in fertility and mortality, many developing countries, including Thailand, have experienced a growing population of elderly people. The proportion of the Thai population aged 60 and over increased from 4.8% in 1960 to 10.5% in 2005, and is likely to reach 25% by 2040. The estimate of 25% for 2040 is similar to the UN projections for many developed countries (United Nations Population Division). Life expectancy at birth was about 75 years for females and 68 years for males in 2006 (Institute for Population and Social Research 2006).

Chai Nat is a province located about 195 km north of Bangkok, the capital city of Thailand. According to the 2000 Population and Housing Census, there were about 400,000 people residing in Chai Nat (National Statistical Office 2002). The sex ratio (males per 100 females) was 92.6. Only 13% of the population lived in urban areas, and more than 60% were engaged in the agricultural sector. Almost all were Buddhists (99.5%). The average number of years of schooling for those aged 15 and over was 6 years, which is below the compulsory education minimum of 9 years. The population aged 55 and over constituted about 20% of the total population.

Key Measures

The measure of happiness

The variable indicating the level of happiness in this study refers to people's subjective assessment of their feeling at the time of the survey. The assessment was given as a response to the question, “At present, how are you feeling?” We did not insert the term “satisfied” or “happy” in order to avoid bias in the question and to allow for less constrained responses since people may feel both happy and unhappy at the same time. More happiness means less unhappiness. The respondents were asked to use an eleven-point scale (0–10) to rate their feeling, with 0 being “unhappiest,” 5 being “not unhappy and not happy,” and 10 being “happiest.” Our scale is similar to that of happiness measurement used in some other studies such as a study by Veenhoven (1997).

The measures of independent variables

To assess economic hardship among the elderly, the criterion of having had any debt over the previous year was used. However, since having debt does not always mean feeling financial strain, the ability to pay back the debt also had to be taken into consideration. In this paper, economic hardship is classified into four types: (1) having no debt at all, (2) having some debt but feeling no debt-burden, (3) having debt and feeling debt-burdened to some extent, and (4) having debt and feeling seriously debt-burdened. We expected that the elderly with no debt or with debt but no feeling of debt-burden would be happier than those characterized by the other two types of economic hardship.

In Thailand, as in many Asian countries, old people have traditionally lived with their children, which provides parents with both material and emotional support. However, recently there has been some evidence that such co-residence has been reduced (Knodel et al. 2005). From our open-ended question regarding the reasons for their happiness rating, most elderly suggested that living with children or “seeing the faces of my own children” everyday made them happy. With regard to feelings of unhappiness, they mentioned that part of their unhappiness was because they were worried about their children who had migrated to work somewhere else. Thus, because of the expected effect of co-residence, we included in the analysis a variable indicating whether the older person lived with his or her children. It was expected that those living with children would be happier than those living in other types of living arrangement.

As a measure of functional ability, an assessment of respondents' ability to perform daily activities was used. The five tasks considered in this assessment are the ability to squat, lift an object weighing 5 kg, walk 1 km, walk up stairs a few steps, and travel by bus or boat alone. If the elderly could perform all these activities without any difficulty, their level of functioning was considered as “very good”. If they could perform at least one of these activities with some difficulty but without any assistance from others, they were considered to have a “good.” level of functioning. The elderly who were considered to have a “poor” level of functioning were those who could not perform any of these activities by themselves and always needed help from others. It was expected that the elderly who had very good level of functional ability would be happier than those in other level groups.

Perceived social support is also employed as one of the predictors of the level of happiness since it has been found to be a powerful factor determining happiness in previous studies (Chan and Lee 2006). In our study, perceived social support was based on one's feeling with regard to one's social environment, as measured by acquaintance with neighbors, reliability of neighbors in times of crisis, mutual trust, and feeling of security in terms of life and property. The elderly were asked a number of questions about their relationships with their neighbors, including (1) how well they knew their neighbors, (2) how their neighbors would react if they needed help, (3) how much they trusted other people, and (4) how safe they felt in terms of their lives and property.

We categorized perceived social support as “very good,” “good,” and “poor.” The “very good” category refers to those who reported that they knew their neighbors well, that they expected to get a good level of help from their neighbors in times of need, that they could borrow things from neighbors whenever they liked, and that they were not worried about their lives and property. If they knew they neighbors well but their reported feeling was “somewhat satisfied” (a level of satisfaction lower than the “very good” category) with these four aspects, they were included in the “good” category. If they did not know their neighbors or only knew they neighbors somewhat but their level of satisfaction with the other three categories was lower than that of the “very good” and “good” categories, they were classified as living in a “poor” social environment. Given the assumption that social environment can influence an individual's level of happiness, we expected that the elderly living in a very good social environment would be the happiest.

Sometimes people may think that security can be gained from possessing more and more goods. The drive toward consumerism or acquisition of possessions is, however, likely to lead to feelings of frustration and dissatisfaction (Tetzel 2003) because they need to earn more and more money to be able to fulfill their unlimited desires. Four types of household possessions were employed to test this notion: telephones (either standard or cell phone), washing machines, air conditioners, and cars/vans/pickups. The index ranges from 0 to 4, which is transformed into five dummy variables (zero item, one item..., 4 items) when used in the regressions to capture the nonlinearity of the effects of the possessions. The effect of the household possessions on the happiness of the elderly is an empirical question. It should be noted that the household possessions question was asked with regard to the household as a whole thereby serving as a proxy for consumption of the elderly. The criterion of selection was that each item should not be universally available. If that were the case, it would be more likely to reflect their socioeconomic status or modernity relative to their respective communities. We expected that those who owned more items would be less happy than those who owned fewer items due to frustration of not earning enough money.

Some of the elderly, despite being relatively poor, nonetheless may feel “content”. This feeling relates to the internal factor of “perceived relative poverty.” We selected and measured this variable because, as noted above, the ability to constrain one's desires by disciplining one's mind so as not to be preoccupied with one's relative poverty is taken as a predictor of happiness (Bhikkhu 2005; Layard 2005).

Specifically, the respondents were asked, “Do you feel poor compared to your neighbors?” The choices for unprompted answers were: “feeling poorer than your neighbors,” “feeling just as poor as your neighbors,” and “not feeling poor.” We hypothesized that those who did not feel poor were more likely to be happier than those who felt poorer than or as poor as their neighbors. This variable normally will be used as a proxy for economic status. However, we also asked those who answered “not feeling poor” why they felt so. Their unprompted answers were: contentment with what one has, support from one's spouse, good health, freedom from debt, having land, having knowledge, support from children, having no family burdens, having a job, and having formal education. The answers, which will be discussed later, suggest that being not feeling poor is due to the feeling of contentment.

Data analysis strategy

Multiple regression analyses are employed. The dependent variable is level of happiness, which is continuous. The independent variables include the components of happiness, which are, namely, demographic factors, external and internal factors. Demographic factors include age and sex. Some studies found a positive relationship while other studies found a negative relationship between age and happiness. However, it is clear that the young and the old are happier than the middle aged (U shape), controlling for health and other factors. Regarding sex, it has been found that women seem to be happier than men, but the difference is not substantial (Frey and Stutzer 2002).

External factors include debts, living arrangement, functional ability, neighborhood environment and household possessions, and the internal factor is relative poverty (feeling of contentment). All independent variables are treated as dummy variables. The exception is age, which is treated as the continuous independent variable.

Results

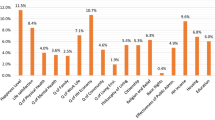

The mean happiness of the population aged 55–80 is 5.7, which is slightly above the feeling of neutral (5) (Table 1). It ranges between 4.6–7.0. The lowest mean happiness is among those who feel that they are poorer than their neighbors. The highest mean happiness is found among those who own all four household possessions (washing machine, telephone, air-conditioner, and car/van/pickup).

Regarding the independent variables of our regression analysis, the proportion of females is higher than that of males (58%). Regarding debts during the previous year, about 69% of the elderly did not have any debt. For those with debt, about 9% reported that it was not a burden for them at all, 13% reported that the debt was a burden to some extent, and the rest reported that their debt was a big/very big burden for them to pay off.

Regarding family structure or type of living arrangement, about 32% of the elderly lived with at least one child with/without spouse and relatives, and about 45% lived with a spouse with/without relatives (but no child). About 13% lived alone, and 10% lived with others who were not relatives.

The elderly who could perform all activities without any difficulty or, in other words, were in “very good category” constitute the highest proportion (65%). The “good category” accounts for 12% while the “poor category” is about 23%.

In terms of social environment, which can significantly influence an individual's level of happiness, about 35% of Chai Nat residents said that they lived in a very good social environment. While 48% indicated that they live in a good community, about 17% indicated that they live in a community where they were acquainted with only a few people, felt a lower level of reliability of neighbors in times of crisis, a lower level of trust in other people, and a higher level of anxiety about both their personal safety and that of their property.

Regarding ownership of the four household possessions (telephone, washing machine, air conditioner, and car/van/pick up),almost half of the elderly had none of these items, about 25% had one item, and only 2% had all four items.

For the feeling of contentment, about 46% reported that they were not poor. The elderly who reported that they were as poor as or poorer than their neighbors constituted about the same proportion, 26% and 28%, respectively. Almost all males and all females who did not feel poor reported that they felt so because they were content with what they had, as shown in Table 2. This finding supports our earlier notion that contentment, at least in the Thai context, depends on the perception of one's relative poverty.

Lacking contentment may lead to unhappiness. Maybe this can explain why people who were at the same consumer level had different levels of happiness, as shown in Table 3. For instance, the elderly who owned none of the consumer items felt either saddest or happiest. Similar results are found among the elderly who owned all four household items. It should be noted that the only elderly who reported “0” (being the saddest) were the ones who had no items or only one item of the household possessions while those with all four household possessions who reported “10” (most happiness) constituted the highest proportion (9%) compared to those who owned fewer items or no items at all.

Results of multiple regression analysis

Table 4 displays three regression models, all of which take happiness as the dependent variable. The R 2 value displayed at the bottom of each model shows the total amount of variance in happiness explained by all the predictors in the model.

In Table 4 we begin our analysis with a focus on the relationship between happiness and demographic factors (age and gender). The results show that only gender is statistically significant and that male elderly are happier than female elderly.

In Model 2 we add all external factors. Being without debt or with debt but not feeling a big burden is strongly associated with greater happiness than being indebted and feeling that it is a big/very big burden. With regard to the family factor, which is one of the elements of happiness, only the elderly who live alone are statistically significantly happier than those living with non-relatives. For functional ability, as measured by the ability to perform various activities in daily life, we find that, as expected, the elderly with “very good” level of functioning are significantly happier than those with merely “good” level or those who had some difficulties in performing an activity in everyday life but who could still perform it by themselves. They were much happier than those with only “poor” level who needed assistance from others for daily living.

Model 2 also shows that the elderly who perceived that they lived in communities where there were many people who were acquainted with one another, where people helped each other, and where people trusted others and felt secure about their lives and property seem to be happier than those with a less positive (and “nurturing”) social environment. In addition, Model 2 shows that ownership of household possessions has a strong positive effect on happiness. The more items they own, the happier they are.

The last model (Model 3) adds the so-called “internal factor” or “inner happiness” relating to relative poverty. The effects of demographic and external factors on happiness do not change very much from the previous model. For the internal factor, the results clearly show that, holding the other factors constant, inner happiness has a significantly positive effect on happiness. For instance, controlling for the number of household possessions they own, the elderly who reported that they were not poor or as poor as their neighbors are significantly happier than those who reported that they were poorer than their neighbors. A report of “no poverty” has a much stronger positive effect than a report of “similar poverty” or “more poverty.” Therefore, we accept the hypothesis that those who did not feel poor were happier than those who felt poorer than or as poor as their neighbors.

Note that the last model, which takes into account inner happiness, explains the level of happiness much better than other models. The R 2 increased significantly from model 2 to model 3 (about 8%) with only one variable, while the increase in the R 2 from model 1 to model 2 with five variables is 13%. It was also found that in Model 3 the partial R 2 of the internal factor accounted for 11%, or half of the explanation of all independent variables on happiness.

Discussions

This paper answers the two research questions originally posed by analyzing surveyed data on well-being indicators in Chai Nat province. The first question concerns the level of happiness of the Thai elderly. It is found that the average happiness level of the respondents is 5.7, which is close to “being not sad and not happy.”

Average happiness differs markedly across nations Veenhoven (1997). A happiness study of 48 nations in many parts of the world in early 1990s by Veenhoven (1997), using the same scale as this study (0–10), found that the average of happiness of people ranged from 4.4 in Bulgaria to 7.9 in the Netherlands, Sweden, Iceland, and Ireland. The average of happiness in the Philippines, the only country in Southeast Asia included in this study, was 6.9. He observed that people were clearly happier in the nations that were more affluent, safe, free, egalitarian, and tolerant. Economic growth added to happiness in poor countries, but not rich ones. However, cultural variation in outlook on life was not attributable to the differences in average happiness. The same study found that happiness was not part of the national character, namely, the idea that some cultures would have a gloomy outlook on life whereas others were more optimistic.

We, however, argued that the finding of average happiness of 5.7 among the Thai elderly may partly reflect their perception of Buddhist teaching to follow a moderate path or avoid the two extremes of happiness and sadness. In addition, remaining calm and indifferent in some situations, such as those that may normally provoke social condemnation, is a prevalent Thai value (Podhisita 1985). Neutral responses among Thai elderly was also found in some other studies, such as Chayovan (2005).

Concerning the second research question, related to factors affecting the level of happiness, external factors and an internal factor were used to assess the effects. It appears from our regressions models that both external and internal factors have significant effects on happiness, but the internal factor, measured by the feeling of contentment, is more important, controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors such as age, gender, debt, household possessions, functional ability, neighborhood environment, and living arrangement.

Evidence shows that Thai elderly who have no debt or had non-burdensome debt tend to feel happier than those with burdensome debt. This finding confirms the previous studies in the West and Asia that financial strain or economic hardship is an important factor behind feelings of depression among older adults (Knesebeck et al. 2003; Li 1995; Chan and Lee 2006).

Controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors and the internal factor, living with children does not have any effect on the level of happiness in later life. This may be due to the fact that many Thai elderly, particularly in rural areas, who do not live with their children have their home near their children's homes. In addition, migration of their children can still contribute positively to their material well-being (through remittances) while their children can still maintain contact and visits.Footnote 3 It should also be noted that a negative relationship between parents and children is also evident. Some parents feel economic burden of children who stay with them (Knodel and Saengtienchai 2005).

We use the ability to perform activities in daily living to reflect the level of functioning of the elderly. The results show that better level leads to greater happiness, as expected. Those who are happier are the ones who do not have to rely on assistance from other people.

The elderly who perceived that they live in a better social environment are found to be happier. This happiness is derived from the feeling of security and reliability at the time of need. This finding is consistent with previous findings that perceived social support to be a powerful factor determining happiness (Chan and Lee 2006; Faber and Wasserman 2002).

In addition, our analyses clearly show that happiness comes from market goods; the more one consumes, the happier one feels. The elderly who own all four selected items (telephone, washing machine, air-conditioner, and car/van/pick-up) are happier than those who own only three items, two items, one item, or none. This finding seems to contradict the notion that if people are above the poverty level, increased income and the possession of more and more material goods have little impact on feelings of happiness (Lane 2000), and that people feel more frustrated about having to earn more money to purchase material goods. In fact, consumerism is not the same as having more money since making a purchase depends on people's attitudes toward money and material values (Tetzel 2003). It reflects, perhaps, that personality preferences among Thai elderly—i. e., they or other members of their households may enjoy displaying high status possessions, particularly a car/van/pick-up. In addition, they may think that all these items are necessary for them in their preferred lifestyle. The elderly themselves perhaps are not the ones who need to earn more and more money to be able to purchase these items. Since they have already passed the stage of building a family and functioning as the main breadwinners, these possessions are what they have already accumulated and now it is the time to enjoy them.

Interestingly, this study reveals, however, that despite the significant effects of external factors, these external factors are not as important as the internal factor of a feeling of relative poverty. Controlling for the external factors, those who feel that they are not poor are significantly happier than those who feel as poor as or poorer than their neighbors. As mentioned earlier, perceived no poverty reflects a feeling of contentment. Almost all of those (99.5% for males and 100% for females) who reported that they were not poor compared to their neighbors felt so because of a feeling of contentment with what they had (Table 2).

Generally, it can be claimed that a feeling of contentment may be influenced by Buddhist philosophy. We found from four focus group discussions among older persons, both males and females, in May 2007 that “feeling satisfied with what one has” is a phrase that the Thais hear throughout their lives and one that has pervaded Thai culture. They agree among themselves that the path to happiness lies in training one's mind not to crave things without limit, particularly when comparing one's economic status to that of neighbors or friends, and so avoiding unnecessarily torturing oneself. They also add that feeling “contentment with what one has” does not prevent them from working hard through fair and righteous means to improve their economic status. However, none knew that this value can also be found in the Buddhist teaching of “Blessings of Life.”Footnote 4 It should be noted that this finding is not surprising since in Thailand one's status as Buddhist is passed on automatically at birth. Thus knowledge of Buddhism among Thai people is at different levels.

Interestingly, a similar philosophy exists in other parts of the world. R. Layard, an economist, argues that people's happiness depends on their “inner selves” or personal values and philosophies of life. “People are happier if they appreciate what they have, whatever it is; if they do not compare themselves with others” (2005: 72).

The findings that variables representing a consumerist worldview and values as well as those reflecting a feeling of contentment are significant and positively associated with happiness in Thailand may reflect the relevance and vitality of both traditional philosophy as well as values associated with the capitalist economy prevailing in contemporary Thai society.

Although external factors should not be ignored, our finding highlights the need for paying special attention to inner happiness among the elderly. Some elderly may feel that they have come repossession of material goods for their overall quality of life since they could not own them when they were much poorer as young people. Those who feel that they never have enough will never be able to quit striving and struggling. They will never find real happiness. Thus a feeling of contentment could influence their happiness, particularly among the poor elderly living in a country where there is great inequality in economic status among the people.

The measure of the inner happiness in this study has, however, been applied only to Thai elderly persons. This measure could be applied in cross-cultural research in other Asian and non-Asian countries, particularly in countries where Buddhism is predominant and in countries with great inequality in economic status. Additionally, since only one internal indicator is used, a wide range of internal indicators should be developed and tested in future research.

In spite of its limitations, this study enhances our understanding of cross-cultural variation by applying several factors that have been tested in several other countries in Asia and the West. Additionally, an internal factor was first tested in this work. If it (or more internal factors) is used in future research in other countries as proposed, this effort can help our understanding as to whether such an internal factor is universal or unique to specific cultures.

Notes

Phra Phaisan Visalo is Abbot of Wat Pa Sukhato and Wat Mahawan in Chaiyaphum, Thailand. He is on the Executive Commitee of Phra Sekhiyadhamma, a nationwide network of socially concerned monks.

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (1906–1993) was one of the most famous Buddhist monks. He was honored by UNESCO by being included in the list of great international personalities in 2005.

The Thai elderly also use cell phones, as found in the study of Knodel and Saengtienchai (2005), and enjoy using cell phones to contact their children who migrate to work somewhere else.

According to Buddhism, there are 38 Blessings of Life, and contentment with what one has is Blessings of Life number 24 (Soni 1987).

References

Alexandrova, A. (2005). Subjective well-being and Kahneman' s objective happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 301–324.

Bhikkhu, B. (1996). Handbook for mankind. Translated from Thai by Ariyananda Bhikkhu (Roderick S. Bucknell). First electronic edition: December 2006. http://www.dharmaweb.org/index.php/Buddhadasa_Bhikkhu.

Bhikkhu, B. (2005). HEART-WOOD from THE BO THREE. Surat Thani: Dhammadana Foundation.

Chan, Y. K., & Lee, R. P. L. (2006). Network size, social support and happiness in later life: A comparative study of Beijing and Hong Kong. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 87–112.

Chayovan, N. (2005). Policy implications for old-age economics support of changes in Thailand's age structure: A new challenge. In S. Tuljapurkar, I. Pool, & V. Prachuabmoh (Eds.) Population, resources and development (pp. 157–179). Netherlands: Springer.

Deiner, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 653–663.

Doniger, W. (consulting editor). (1999). Merriam-Webster' s encyclopedia of world religions. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Economic Journal, 111(473), 465–484.

Easterlin, R. A. (2005). Is there an iron law of happiness? Unpublished working paper, Department of Economics, University of Southern California.

Faber, A. D., & Wasserman, S. (2002). Social support and social networks: Synthesis and review. In J. A. Levy, & B. A. Pescosolido (Eds.) Social networks and health (pp. 29–72). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

George, L. K. (1992). Economic status and subjective well-being: A review of the literature and an agenda for future research. In N. E. Cutler, D. W. Gregg, & M. P. Lawton (Eds.) Age, money and life satisfaction: Aspects of financial gerontology (pp. 1–21). NY: Springer.

Herzog, A. R., & Rodgers, W. L. (1981). The structure of subjective well-being in different age groups. Journal of Gerontology, 36(4), 472–479.

Heylighen, F. (1992). A cognitive–systemic reconstruction of Maslow's theory of self-actualization. Behavioral Science, 37, 39–58.

Ho, S-C., Woo, J., Lau, U., Chan, S-G., Yuen, Y-K., Chan, Y-K., & Chi, I. (1995). Life satisfaction and associated factors in older Hong Kong Chinese. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 43, 252–255.

Ingersoll-Dayton, B., Saengtienchai, C., Kespichyawattana, J., & Aungsuroach, Y. (2004). Measuring psychological well-being: Insights from Thai elders. The Gerontological Society of America, 44(5), 596–604.

Inglehart, R., & Klingemannh, H. (2000). Cultural and subjective well-being. In E. Diener, & E. M. Suh (Eds.) Genes, culture, democracy, and happiness (p. 171). Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Institute for Population and Social Research. (2006). Population Gazette 2006. Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University.

Knesebeck, O. v. d., Luschen, G., Cockerham, W. C., & Siegrist, J. (2003). Socioeconomic status and health among the aged in the United States and Germany: A comparative cross-sectional study. Social Science and Medicine, 57, 1643–1652.

Knodel, J., Chamratrithirong, A., & Debavalaya, N. (1987). Thailand's reproductive revolution rapid fertility decline in a third-world setting. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

Knodel, J., Chayovan, N., Mithranon, P., Amornsirisomboon, P., & Arunraksombat, S. (2005). Thailand' s older population: Social and economic support as assessed in 2002, Population Studies Center, University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research. Research report 05-471.

Knodel, J., & Saengtienchai, C. (2005). Rural parents with urban children: Social and economic implications of migration on the rural elderly in Thailand, Population Studies Center, University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research. Research report 05-574.

Kohler, H-P., Behrman, J. R., & Skytthe, A. (2005). Partner children = happiness? The effects of partnerships and fertility on well-being. Population and Development Review, 31(3), 407–445.

Krause, N., Liang, J., & Gu, S. (1998). Financial strain, received support, anticipated support, and depressive symptoms in the People's Republic of China. Psychology and Aging, 13, 58–68.

Lane, R. E. (2000). The loss of happiness in market economies. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. London: Allen Lane.

Li, L. (1995). Subjective well being of Chinese urban elderly. International Review of Modern Sociology, 25, 17–26.

Liu, X., Liang, J., & Gu, S. (1995). Flows of social support and health status among older persons in China. Social Science and Medicine, 41(8), 1175–1184.

Max, H., & Markus, H. (2006). How social relations and structures can produce happiness and unhappiness: An international comparative analysis. Social Indicators, 75(2), 169–216.

Meng, C., & Xiang, M. (1997). Factors influencing the psychological well-being of elderly people: A 2 year follow-up study. Chinese Medical Health Journal, 11, 273–275.

National Statistical Office (2002). Population and housing indicators in Thailand: Based on population and housing census data: 1980, 1990 and 2000. Thailand: National Statistical Office.

Pei, X., & Pillai, V. K. (1999). Old age support in China: The role of the state and family. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 49(3), 197–212.

Phongpaichit, P., & Baker, C. (2004). THAKSIN the business of politics in Thailand. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Pinquart, M., & Sorensen, S. (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later-life. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 187–224.

Podhisita, C. (1985). Buddhism and the Thai world view. In A. Pongsapich, et al. (Ed.) Traditional and changing Thai world view (pp. 25–33). Bangkok: Social Science Research Institute, Chulalongkorn University.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything or is it? Exploration on the meaning of psychological well being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Silverman, P., Hecht, L., & McMillin, D. J. (2000). Modeling life satisfaction among the aged: A comparison of Chinese and Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 15(4), 289–305.

Soni, R. L. (1987). Life's highest blessings the maha mangala sutta. The Wheel Publication no. 254/256. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.

Tetzel, M. (2003). The art of buying: Coming to terms with money and materialism. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4, 405–435.

United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospect: The 2004 Revision online database. http://www.esa.un.org/unpp/index.asp?panel=2.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24, 1–34.

Veenhoven, R. (1997). Advances in understanding happiness. Revue Quebecoise de Psychologie 18, 29–74. English version available on line http://www.eur.nl/fsw/personeel/happiness/.

Visalo, P. P. (1998). Spiritual materialism and sacraments of consumerism: A view from Thailand. Seeds of Peace, 14(3), 24–25.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gray, R.S., Rukumnuaykit, P., Kittisuksathit, S. et al. Inner Happiness Among Thai Elderly. J Cross Cult Gerontol 23, 211–224 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-008-9065-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-008-9065-7