Abstract

Despite extensive literature on female mate choice, empirical evidence on women’s mating preferences in the search for a sperm donor is scarce, even though this search, by isolating a male’s genetic impact on offspring from other factors like paternal investment, offers a naturally ”controlled” research setting. In this paper, we work to fill this void by examining the rapidly growing online sperm donor market, which is raising new challenges by offering women novel ways to seek out donor sperm. We not only identify individual factors that influence women’s mating preferences but find strong support for the proposition that behavioural traits (inner values) are more important in these choices than physical appearance (exterior values). We also report evidence that physical factors matter more than resources or other external cues of material success, perhaps because the relevance of good character in donor selection is part of a female psychological adaptation throughout evolutionary history. The lack of evidence on a preference for material resources, on the other hand, may indicate the ability of peer socialization and better access to resources to rapidly shape the female decision process. Overall, the paper makes useful contributions to both the literature on human behaviour and that on decision-making in extreme and highly important situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sterility has been said to be the bane of horticulture; but on this view we owe variability to the same cause which produces sterility: and variability is the source of all the choicest productions of the garden.

Charles Darwin (1872), Origin of the Species

For many months, Beth Gardner and her wife, Nicole, had been looking for someone to help them conceive. They began with sperm banks, which have donors of almost every background, searchable by religion, ancestry, even the celebrity they most resemble. But the couple balked at the prices—at least $2,000 for the sperm alone—and the fact that most donors were anonymous; they wanted their child to have the option to one day know his or her father. So in the summer of 2010, at home with their two dogs and three cats, Beth and Nicole typed these words into a search engine: “free sperm donor”.

Tony Dokoupil, “Free Sperm Donors” and the Women Who Want Them.

1 Introduction

Despite knowing a great deal about the way values shape people’s daily interactions in families, neighbourhoods, or work groups, we have only limited (economic) understanding of their role in the making of extreme, large-scale, or permanent decisions. Such decision-making is typified by choices related to reproduction and the creation of life, especially those that involve the search for a sperm donor in the (informalFootnote 1) online sperm donation market. In this paper, therefore, we seek to understand the degree to which females searching for a donor care about internal attributes like kindness or reliability as opposed to external attributes like physical attractiveness, height, weight, eye and hair colour, skin complexion, or about exterior resource measures like occupation and income as indicators of material success. We also look at openness and explore the importance of educational level as a possible proxy for ability. This examination of women’s preferences under a non-sequential mate choice mechanism should increase our understanding of the decision-making process in contexts characterized by increased information and choice. In particular, by taking advantage of the removal of the historical unpredictability of the mate search and its effect on mate choice outcomes, it should provide unique and valuable insights into how social norms shape an individual’s preferences in the context of arguably the largest economic decision that humans can make (i.e., offspring).

The advantage of studying behaviour related to such a major decision is that donation recipients are forced to reveal their true preferences prior to the consumption decision, a scenario that is quite rare (Waynforth and Dunbar 1995; Pawłowski and Dunbar 1999). Moreover, in contrast to the limited choices offered by private sperm banks in which expressed preferences may be biased by availability, the Internet sperm market offers a much larger option set with greater potential for locating the desired characteristics. Recipients in the online sperm donation market, therefore, have a strong incentive to maximize their chances of finding the closest match to their stated preferences in order to reduce any potential search costs and future negative externalities.

For many years before the advent of this new market, women had access only to limited non-identifying donor information and had (comparatively) less say in donor choice. In most cases, this latter was made at the physician or nurse’s discretion, dependent mainly on physical similarity to the women’s partner so as to increase acceptance (Scheib 1997). The rationale for this practice was the desire to “invoke a biological relationship” (Burr 2009, p. 716) even when there was no genetic tie (see also Kirkman 2004; Hargreaves 2006). This limited access may explain why the empirical literature on recipient preferences is substantially less developed (Scheib et al. 2000; Riggs and Russell 2010; Rodino et al. 2011; Bossema et al. 2014) than that on extensively explored topics like mate selection, which goes back to early work by Hill (1945) or Christensen (1947). In general, despite millions of dollars poured into in-vitro fertilization (IVF) research worldwide, the literature and research on recipient preferences is notably underdeveloped (Riggs and Russell 2010). In fact, much of the current research on donor insemination (DI) focuses on the increase in both recipient and donor support of disclosure to offspring (e.g., Brewaeys 2005; Daniels 2007; Thorn et al. 2008; Daniels et al. 2009) even in countries with strong legal frameworks upholding donor anonymity.

The communicative ability of the Internet and social media, however, has greatly changed the industry, eliminating past scenarios in which some potential recipients (e.g., single women) may have been rejected because of social concerns. They may, for example, have been considered “unsuitable” because of inadequate relationships or social support; traumatic and unresolved family histories; limited financial resources; psychological instability; or an unhealthy desire for, the lack of a male role model for, or stigmatization of the child (Klock et al. 1996). In many instances, such biases may have been unreasonable; for example, Klock et al. (1996) identified no significant differences in reported levels of psychiatric symptomatology or self-esteem between single and married women seeking DI. Rather, both groups showed low levels of psychiatric distress and average levels of self-esteem. Likewise, Acker (2013), after exploring the risks and benefits of private and institutionalized sperm donation, stressed that the “benefits of unregulated private sperm transactions outweigh the risks, which are not so substantial than they warrant an intrusion into a woman’s right to choose the method of her impregnation” (p. 3). Nevertheless, the development of the online sperm donation market, while expanding opportunities for donor location, has increased risks to recipients, which raises new challenges for legislators.

2 Female mate choice

Evolutionary psychology seeks to solve survival and reproduction problems by identifying mental adaptations that have been shaped over eons (Miller and Todd 1998). Hence, because historically humans have spent most of their time as hunter-gatherers (Lancaster 1991), evolutionary theories suggest that human mating is strategic, and related choices (whether conscious or unconscious) are made to maximize some entity, match, or balance. Accordingly, the sex that invests more in offspring is likely to be more discriminating about its mates (Buss and Schmitt 1993, p. 205). Among mammals, it is the female that usually invests more heavily than the male, so female humans have tended to prefer males with a drive to acquire, bond, learn, and defend:

First, they would select a male with wealth and status or, at least, a likely bread-winner with ambition; a person with a drive to acquire. They wanted not only a good hunter but one who would actually bring the bacon home; a person with a drive to bond. Third, they would be looking for someone who was not only smart but who seemed reliable, committed to using his brain to figure things out on a consistent basis; a person with a drive to learn. Fourth and finally, these females would be looking for someone who was healthy and strong and prepared to protect them from all hazards: a person with a drive to defend. (Lawrence and Nohria 2002, p. 176)

Intersexual selection, therefore, is based on the power to “charm the females”, although it must also be complemented by intrasexual selection, the power to “conquer other males in battle” (Symons 1980, p. 172). Same-sex rivals are competitively excluded from the mating opportunity through threat and force, allowing the winners to bar losers from proximity to potential mates (Puts 2010). Nevertheless, sexual selection is also accomplished by other mechanisms, including “scrambling”, the process of finding a mate before rivals do (Andersson and Iwasa 1996). There is also some evidence that in humans, male reproductive success is linked to cultural success or status as defined by resources, power, and prestige (see, e.g., Flinn 1986; Townsend 1989; Mulder 1990; Pérusse 1993; Li et al. 2002).

Such preferences are likely to be driven by the fact that females bear a heavy biological burden of gestation, birth, and lactation and that children develop slowly to reproductive age, meaning that females need assistance to successfully rear their young (Lancaster 1991). Reproductive strategies can thus be seen as a female attempt to map ways of directly or indirectly controlling necessary resources (Lancaster 1991). Among mammals especially, there is an asymmetry in parental investment, with females investing more in their offspring than males, which creates pressure on females to be discriminating in selection and avoid bad choices (Scheib 1997). In this context, necessary resources provide females and offspring immediate material advantages, as well as social and economic benefits (enhanced reproductive advantages for offspring) and genetic reproductive advantage (assuming that variation in the qualities leading to resource acquisition is partly heritable) (Buss 1989, p. 2). Hence, Powers (1971), in a compilation of the results from six studies conducted between 1939 and 1967, observed that female students tend to rank emotional stability first, followed by ambition, a pleasing disposition, good health, refinement, desire for home and children, education and intelligence, similar educational background and religion, good financial prospects, chastity, favourable social status, and political background, with good looks placed last on the list. In another study, the 10 (out of 75) characteristics most valued in a mate by both males and females were being a good companion, considerate, honest, affectionate, dependable, intelligent, kind, understanding, interesting to talk to, and loyal. The characteristics not viewed as highly desirable were wanting a large family and being dominant, agnostic, a night owl, an early riser, tall, and wealthy (Buss and Barnes 1986).

Of course, an assumption that variation in the qualities leading to resource acquisition is partly inheritable is not necessary for a genetic reproductive advantage to be important. Buss et al. (2001), for example, in a study of mate preferences across a 57-year span, observed that the importance attached to good looks has increased. There is also evidence in humans that women may value physical attractiveness in their potential mates as a signal of some type of genetic benefit (Gangestad and Buss 1993; Gangestad et al. 1994); for example, superior immunocompetence (Puts 2010). Specifically, physical attractiveness may be used as the basis for evaluating a potential mate’s pathogen resistance, one developed over time through sexual selection of “good genes” (Gangestad and Buss 1993, p. 89). Leiblum et al. (1995) likewise identified the physical attributes of ethnicity, height, weight, hair colour, eye colour, and skin tone as six of the top seven characteristics selected by recipients choosing a donor, with “years of college” as number one. These six physical attributes were followed by occupation, special interests, body build, religion, and blood type. In circumstances such as extra-pair relationships, in which the woman may receive nothing but gametes, it seems logical that attractiveness will be more valuable than good character. Nevertheless, although sperm donation is just such a context, it is evolutionarily novel and so not yet likely to be linked to any adaptations other than those that fit similar contexts or are consistently present in humans.

To emphasize the importance of parental engagement aspects that go beyond the cost (down) side Trivers (1972), (Trivers 2002), coined the phrase “parental investment” as an alternative to Fisher’s (1958) “parental expenditures”. This new terminology is part of a theoretical framework for understanding how natural selection acts on the sexes, one emphasizing that sexual selection favours different male and female reproductive strategies and interests. In other words, sex differences in mate preferences reflect differences in the adaptive problems that ancestral men and women faced when choosing a mate (Buss 1995). As a result, the literature has tended to focus in detail on sex differences in mate selection criteria. Kenrick et al. (1990, p. 108), for example, reported that females are generally more selective than males for the following characteristics: power, wealth, high social status, dominance, ambition, popularity, desire for children, good heredity, good housekeeping, religiosity, and emotional stability. On the other hand, such differences in mate selection criteria could be driven by differential socialization and access to resources that may fade from importance as women become more financially autonomous (the “structural powerlessness hypothesis”, see, e.g., Townsend 1989; Buss et al. 2001).

After examining sex differences in human mate preferences among 37 cultures, Buss (1989) reported that females in 36 of these cultures valued good financial prospects in a potential mate more highly than do males, and female subjects in general tended to express higher preferences for ambition-industriousness than males (statistically significant in 29 cultures). The males, in contrast, preferred mates who were younger and placed a higher value on physical attractiveness. This difference was confirmed by Buss and Barnes (1986), who found that women want a spouse to have a good family background and be considerate, honest, dependable, kind, understanding, fond of children, well-liked by others, ambitious, career-oriented, and tall, while men seek a female who is physically attractive, good looking, a good cook, and frugal. Other desirable characteristics include moral traits, which may serve as a signal of individual fitness (Miller 2007), as well as cooperative behaviour, generosity, and altruism, which may increase reproductive success for males (Gurven et al. 2000; Alvard and Gillespie 2004). The mate choice literature, however, has focused less on psychological traits such as kindness and more on physical or visual cues, which are relatively easier to measure (Miller and Todd 1998).

Nevertheless, it still remains unclear to what extent the selection process is driven by the female’s desire for her offspring to have traits similar to the male’s and to what degree, by her wish to guarantee the male’s contribution of important skills that will increase her success in raising them. Miller (2007) described this lack clarity as follows: “The problem is that these studies have not been able to distinguish whether the moral virtues are preferred because they signal good genes, good parents, and/or good partners” (p. 110). He also provided some suggestions for how to proceed, stressing that “[m]uch more research is needed along these lines” (p. 82). Our focus on females searching for a sperm donor in the online market successfully addresses this research weakness because it has the following advantage: even though some character traits may reduce anticipated problems in child rearing, it isolates trait preferences from the desire for parenting assistance. In other words, the more controlled setting ensures that a male’s genetic impact on his offspring can be isolated from other factors and explored independently (Scheib 1997).

In particular, we examine the relevance of perceived “good genes” when the characteristics of a “good parent” are ignored. Interestingly, Kirkpatrick and Ryan (1991), while studying the preference for elaborate mating displays among females that receive little more from the male of their species than sperm, found growing support for the direct selection hypothesis of mating preference evolution. That is, “preferences evolve because of their direct effects on female fitness rather than the genetic effects on offspring resulting from mate choice” (p. 33). If this assumption is true, because human infants require greater paternal investment than other male mammals, individuals may care less about the paternal investment factors (e.g., kindness and reliability) that contribute to cooperative work.

The evidence, in fact, paints a very different picture. Scheib (1994) and Scheib et al. (1997) found that women seeking a sperm donor value the same attributes as they would in a long-term marital partner, such as those that indicate good companionship (see also Scheib 1997). Similarly, Klock et al. (1996) identified “personality” as the second (third) highest rated information variable requested by a single (married) woman selecting a potential donor. In their study, personality had a higher frequency than ethnicity, intelligence, or family medical history among both single and married females. This similarity between preferences for a donor and those for a potential spouse can be explained by the evolutionary perspective: if long-term relationships are the human solution to the survival and reproductive problems faced by our ancestors (Buss 1995), then the psychological mechanisms dealing with this element will occupy a central place in the human evolutionary process, one that may still be reflected in sperm donor choice.

3 Methods

3.1 Data collection

Participants for our survey, conducted between 23 November, 2012, and March 1, 2013, were recruited by posting survey URLs, a short outline of the research, and a call for volunteers on both regulated and semi-regulated sites, as well as on several unregulated free forums.Footnote 2 The first post became active on or just after the initial start date of November 23, 2012, with a short time lag on paid regulated sitesFootnote 3 requiring prior administrator permission. A second blog, again calling for volunteers, was posted on January 4, 2013; and a final blog was posted on January 31, 2013. All three blogs were reviewed and cleared by QUT Ethics prior to uploading (QUT Ethics Approval Number 1200000106). The standardization of these three blog posts was imperative to eliminating any influence over participants or any bias within the sample, as was the absence of any research team participation. That is, over the course of the research, no researcher joined any web site as a participant or engaged in any interaction or commentary on any of the forums, and on all unregulated sites, the posts were clearly identified as research based.

Throughout November 2012, we also collected email addresses from both donors and recipients who had posted them on sites identified as part of a public forum. On December 19, 2012, a mass email containing the text of the first post and the two survey URLs were sent to approximately 1,200 individual email addresses (identified as previous or current participants) across a range of free forum web sites. Several hundred of these email accounts were later found to be deactivated. Moreover, many online participants use multiple accounts across multiple websites and forums. As with many other studies, our response rate was also negatively affected by the inconsistent disclosure and paternity laws across regions (Shapo 2006), which led to a lower willingness among both recipients and donors to supply personal information, even for independent research purposes. In total, 254 individuals read the abstract provided; however, our analysis focuses on 74 women who completed the survey questionnaire in full.Footnote 4 This sample, although not large, is larger than that in many studies using student populations rather than actual sperm recipients.

The survey questionnaire asked the sperm recipients to complete a range of demographic itemsFootnote 5, a BIG 5 personality test (Saucier 1994), and a range of questions relating to their ideal donor. Participants were also asked to rank 15 characteristics (internal and external) based on their importance in the donor decision on a scale ranging from “not relevant at all” to “an essential requirement”. According to the summary statistics provided in Appendix Table 1, only 35 % of the women in our sample were heterosexual and only 34 %, single. Not surprisingly, the online sperm donor market is attractive to lesbian couples or single women without male partners, particularly because in some countries (e.g., the U.S.), insurance does not cover donor insemination unless a woman can report inability to become pregnant (Dokoupil 2011). Of these 74 women, 91 % were Caucasian, originating from six different continents, although almost a third (31.9 %) were from the U.S., followed by Australia and the UK (at 24.6 % each). Their ages ranged between 19 and 43 with an average of 32, and their perceived healthFootnote 6 and well-beingFootnote 7 scored an average 5.4 and 5.6 (out of 7), respectively.

Because some may criticize our focus on preferences rather than actual choices, it is important to stress that choices are a manifestation of preferences (Cotton et al. 2006). In fact, there is substantial evidence that self-reported data are often consistent with behavioural measures (see Scheib et al. 1997, for an overview). For example, a validity test by Buss (1989) of whether self-reported preferences are accurate indices of actual preferences indicated that actual age differences at marriage reflect preferred age differences between spouses while preferred age at marriage and preferred mate age correspond closely in absolute value to the actual mean ages of grooms and brides. Buss (1989) also found that across countries, samples preferring larger (smaller) age differences tended to reside in countries in which actual marriages are associated with larger (smaller) age differences. Moreover, as stressed by Scheib et al. (1997), when women can choose the insemination donor, they usually do so based on a self-reported questionnaire, and “what women say they want is what they get” (p. 144). This matching may be even stronger in the online sperm donor market.

3.2 Analyses

To more accurately understand the interplay and importance of a recipient’s preference for a particular attribute, we conducted both descriptive and multivariate analyses of the 15 internal and external characteristics that the participants ranked by importance. In doing so, we not only explored which variables may explain recipients’ preferences but also identify what drives the relative strength of inner versus exterior values. The results of using these attributes as dependent variables to explore the determinants of preference are given in Tables 2 and 3, which for brevity report only simple ordinary least squares (OLS) estimations. It should be noted, however, that our estimations using an ordered probit model were relatively similar, with even more factors being statistically significant. It is also worth noting that Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004), using panel data, showed that the choice of a cardinality or ordinality assumption is relatively unimportant when exploring general satisfaction (well-being), whereas the manner in which time-invariant unobserved factors are accounted for definitely matters. We report estimations with standard errors clustered over six regions (continents) to take into account cultural differences. As a precaution, we also applied the Ramsey regression equation specification error test (RESET) for linear regression models, whose null hypothesis of no omitted variables indicates a specification error. This null was rejected for only one of 21 estimations, whose score was also on the border of rejection \((\hbox {Prob} > \hbox {F} = 0.0833)\).

As independent variables, we used only recipient characteristics, employing the same set in all 15 regressions. As a first set of independent variables, we used recipient’s age, education, household’s annual wage. In selecting these variables, we took into account that women’s standards and preferences can be affected by their own potential earning power, occupation status and conditions. We also controlled for subjective health and well-being, followed by marital status (with single as the reference group), religiosity (with a dummy for atheist), and the Big Five personality test variables used in earlier research to predict women’s preferences when choosing a mate: agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, extraversion, and openness (see the appendix). Of these, Welling et al. (2009) found extraversion to be positively correlated with women’s preferences for masculine men, while openness to experience has been associated with women’s preferences for femininity in both men and women. In other research using the Big Five, Botwin et al. (1997) identified significant differences for women with respect to agreeableness, emotional stability, and conscientiousness, although both sexes had consistently high values for openness and agreeableness as desirable qualities in a mate. Such factors as agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability, it should be noted, may have been important for survival in a hominid group (for a discussion, see Kenrick et al. 1990). Moreover, there is evidence that conscientiousness and agreeableness are seen as predictive of good partners and often sought in long-term mates, which could indicate that they have been shaped by sexual selection (for an overview, see Miller 2007).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive analysis

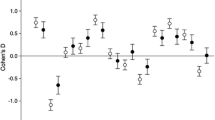

According to the survey results graphed in Fig. 1, character traits like reliability, openness, and kindness rank highly, implying that these inner attributes are perceived as very important. Income, a general indicator of material success, ranks lowest, slightly below political views and religious beliefs, two factors whose potential for genetic determination is likely to be limited. Occupation also does not seem to matter, although education is seen as more important. Nevertheless, it ranks below physical attractiveness and physical indicators like eye colour, skin complexion, weight, and height, with only hair colour rated as less relevant than education. Height seems more important than weight, and physical attractiveness is rated more highly than these other factors.

4.2 Multivariate analysis

As Table 2 shows, recipient age is positively correlated with preferences for donor height, while donor eye colour and skin complexion are less relevant for the older cohort. Recipient education seems not to matter at all when selecting for physical characteristics, while recipient’s annual household wage is negatively correlated with the dependent variable for ethnic group. Healthier recipients seem to care more about height and weight than others, but these factors are less important for happier recipients. In fact, the estimated regression coefficient for happiness indicates that with each additional one unit increase on the happiness scale, the importance of weight decreases an average of 0.240 points.

For the three marital status groupings developed, there is a tendency for single recipients (the reference group), to care less about physical attributes than other recipients (heterosexual and same-sex couples), particularly those in a heterosexual relationship. Religiosity also appears irrelevant in most cases, as does openness (whose coefficient is never statistically significant). Interestingly, agreeableness is positively correlated with the importance of such attributes as weight, hair colour, and physical attractiveness, while conscientiousness is negatively correlated with height. Ethnic group preference, on the other hand, is positively correlated with emotional stability and extraversion.

As indicated in Table 3, both recipient age and household income is seemingly irrelevant, while recipient education is correlated with preferences for both education and kindness. Surprisingly, happier recipients seem to care less about inner attributes like kindness, reliability, and openness, while healthier recipients care more about reliability, openness, and political views. Heterosexual couples appear to care less than singles about donors’ resources and viewpoints (e.g., type/level of education and political views) and more for internal factors (kindness and openness). As might be expected, atheists care less about religious beliefs and more about kindness, reliability and openness. Across the entire sample, agreeableness is negatively correlated with educational preference, but conscientiousness is positively correlated with income. Recipients with higher emotional stability care more about donor occupation, education level, openness and kindness, although their preferences for kindness are negatively correlated with higher openness. Extraverts have a strong preference for openness, which is positively correlated with occupational preference.

Table 4 reports the results of assessing the relative strength of inner (kindness, reliability) versus exterior values (income, occupation, physical attractiveness) by deriving the differences between inner and exterior individual scores. To find the value differences, we have subtracted the individual score for an exterior value like income from that for an inner value like kindness (calculation: kindness score—income score). Then, to use the kindness/income relation as an example, if individual A has a higher positive value than individual B, she has a higher preference for kindness over income. The first three columns of the table report the kindness relations; the last three, the reliability relations.

As Table 4 also shows, atheists care more about kindness and less about income, while older, happier, and more open recipients care less about inner values. On the other hand, when occupation is substituted for income (column 2), atheists again care more about openness, but older and more open recipients care more about occupation. In addition, the results for physical attractiveness relative to kindness (column 3) reinforce the earlier results from Table 2 in that heterosexual couples, as opposed to singles, care more about physical appearance than internal values. On the other hand, no statistically significant difference emerges between same-sex couples and singles. In terms of the reliability-income relation (column 4), healthier women appear to care relatively more about reliability than about income, but increasingly less the older they are. Atheists also care more about reliability than income. For occupational preference relative to reliability (column 5), no factors seem significant. Finally, being in a heterosexual relationship is positively linked to a preference for reliability over physical attractiveness

5 Discussion

Interestingly, in the descriptive analysis, ethnic group ranks highly, which not only aligns with previous literature on assortative mating (Buss and Barnes 1986, Buss 1995) but may also indicate that identification and identity matter. The fact that occupation is not perceived as important (although it does matter) possibly implies its use as a more accurate proxy of potential, ability, or capacity. From an evolutionary perspective, education may matter because it contributes to ensuring offspring survival, particularly in unexpected or adaptive situations. Although our descriptive statistics do not allow for female/male comparison, our results do suggest that, relatively, women care less about socioeconomic status than physical attractiveness, which implies that females have a certain “standard of beauty”. It is particularly interesting that according to our multivariate analysis (Table 2), happier recipients care less about weight than others. These results align with Becker et al.’s (2005) contention that “resemblance is seen as the outward, bodily expression of biological relationships” (p. 1301; see also Becker 2000).

Overall, our examination of the internal and external attributes of women seeking sperm donors in the online donation market and the donor characteristics they are seeking strongly suggests that female recipients care more about a donor’s inner values than exterior traits, with reliability being the most important, followed by openness and kindness. Hence, it would be reasonable to assume that even though women are looking for “just sperm”, they place a high value on their donor being reasonable, willing to participate as arranged, and able to keep his word. In fact, these traits are also well-documented as preferred characteristics in a long-term mate. What remains unclear, however, is whether women place greater emphasis on these donor traits to reduce the emotional and logistical reality of participating in the online sperm donation market or purely as a paternal endowment for the resulting offspring.

The next most important traits appear to be physical characteristics such as ethnicity, physical attractiveness, height, skin complexion, eye colour, and weight. Educational level, although it seems to matter more than occupation and income, like them does not receive a high rating. Income is the least important factor, preceded by religious and political beliefs or views.

Overall, like Scheib (1994) and Scheib et al.’s (1997) analyses for Canada and Norway, our study provides evidence that character is more important than physical attributes, abilities, and resources, a remarkable finding given prior research evidence that character values are perceived as less likely to be biologically transmitted (Scheib 1997). As one explanation for this anomaly, Scheib et al. (1997) and Scheib (1997) have suggested that it could be driven by the psychology of long-term mate selection developed over an evolutionary history in which reproduction and mate choice were inseparable. This assumption is supported by our own multinational data, taken from across an online sperm donor market whose importance is growing with the increasing role of social networking for women seeking donor sperm (Acker 2013). On the other hand, the lack of evidence on any preference for material resources may indicate that, from an evolutionary perspective, peer socialization (Harris 1995, 2011) and better access to resources can have a rapid impact on female choices.

6 Limitations

One limitation of our study design is that is does not account for any potential differences between what women claim or the ratings they provide and how they choose a donor. For example, the most important factors might drop in importance during the actual choice process. It is also possible that the nature of the online market may change the contextual importance of the variables measured. That is, because we specifically asked participants to stipulate that they were actively searching for a sperm donor rather than simply looking at web sites, our analysis concentrates only on women engaged in a serious search process. in such a market, where men make themselves directly available to women, positive factors like reliability or kindness, which reduce harmful or deceptive behaviour, might arguably become more salient than when choosing donors through a middleman or sperm bank, where recipients are not allowed to contact donors. Hence, the high value of factors like reliability, kindness, or even openness might be driven by the very nature of the transaction, which depends on the potential male donor holding up his end of the bargain. We also acknowledge that regional differences in donor anonymity legislation may influence recipient preferences and that more research is needed into how non-heterosexual couples negotiate donor conception (Nordqvist 2012).

What must also be considered in any evolutionary discussion is that the women who seek sperm donors come (in the majority) from specific (WEIRD) environments (Western, industrialized, rich, democratic, educated nations) and thus have many material resources. Such plenty stands in stark contrast to the reality of women in ancestral environments in which caloric resources especially tended to be a life-or-death factor. Hence, for our analysis, there is no ready baseline treatment or comparative data set.

7 Conclusions

Our findings make a particularly useful contribution to the literature on human decisions in extreme situations (see, e.g., Frey et al. 2010, Elinder and Erixson 2012) by providing evidence that even in life-altering circumstances, individuals still care about social norms. The unique setting of our research is especially valuable in that the female recipients’ preferences are less constrained than in the standard sperm bank context on which previous studies have focused. In particular, a woman’s search for sperm donation in the online market is one of a limited number of human mating practices and patterns (Waynforth and Dunbar 1995; Pawłowski and Dunbar 1999) in which participants are forced to reveal their true preferences. That is, by participating in this market place, women can effectively remove the unpredictability and constraints of traditional mating patterns, thereby engaging in optimal decision-making under sequential periodic evaluation. Nevertheless, further research is needed on what this increased information and choice means for women and for human mating outcomes.

Our investigation also goes beyond previous research by exploring how individual recipients’ characteristics shape their preferences for donor traits. In particular, we explore the importance of inner versus exterior values, providing strong evidence that although individual characteristics matter, their influence depends greatly on the inner and exterior values considered. Our findings also provide a springboard for academic research into online sperm donation, which, despite a vast body of literature on mating through the Internet, is in its infancy, with only a limited number of studies to date (Riggs and Russell 2010). It is for both these reasons that we put forward this research as a primer for future study even while acknowledging that our sample is small, heterogeneous, and potentially biased. Future research into online sperm donation, for example, might examine such aspects as the changing motivations of donors and recipients, and assortative mating. It might also take a closer look at how donor sperm shortages affect which donors are chosen.

What is abundantly clear is that the Internet is providing new and unique sperm donor opportunities that increase availability for both donor and recipient and reduce the latter’s individual costs. This online market goes far beyond the minimalism of the “mating by proxy” offered in traditional sperm banks and assisted reproductive technology facilities, wherein “women vicariously ‘mate’ with men selected on the basis of donor characteristics outlined in clinic proforma” (Rodino et al. 2011, p. 998). Nevertheless, this new market place also raises new and unique challenges, not only for the male and female participants, but also for legislators and policymakers, whose decisions may be somewhat informed by the findings reported here.

Notes

For example, through contacts on the Internet rather than such formal channels as assisted reproduction clinics (Bossema et al. 2014).

VoyForum.com, TadpoleTown.com, BubHub.com, FertilityFriends.co.uk—Infertility and Fertility Support, PSD (privatespermdonor.com).

Twenty-one others provided barely any information and so were excluded from our analysis.

Educational level was measured by the following question: My highest level of education achieved at this point in time (1 = below grade 10, 2 = grade 10, 3 = grade 11, 4 = grade 12, 5 = technical college (prevocational, trade college, apprenticeship), 6 = undergraduate university study (diploma, bachelor’s), 7 = post-graduate university study (graduate diploma, graduate certificate, master’s), 8 = doctorate/PhD. A similar item assessed income: My household’s annual wage would be in the range of 1 = below $20,000, 2 = $20,000 – $50,000, 3 = $50,000 -$80,000, 4 = $80,000 – $110,000, 5 = $110,000 – $150,000, 6 = $150,000 – $180,000, 7 = $180,000 – $210,000, 8 = $210,000 – $240,000, 9 = $240,000 – $270,000, 10 = $270,000 – $300,000, 11= above $300,000.

Height was scaled as follows: 9 = over 220 cm (taller than 7 ft 1 in), 8 = 210–220 cm (6 ft 11 in–7 ft 1 in), 7 = 200–210 cm (6 ft 7 in–6 ft 11 in), 6 = 190–200 cm (6 ft 3 in–6 ft 7 in), 5 = 180–190 cm (5 ft 11 in–6 ft 3 in), 4 = 170–180 cm (5 ft 7 in–5 ft 11 in), 3 = 160–170 cm (5 ft 3 in–5 ft 7 in), 2 = 150–160 cm (4 ft 11 in–5 ft 3 in), 1 = under 150 cm (shorter than 4 ft 11 in). Weight was similarly ranked: 1 = under 50 kg (110 lb), 2 = 50–60 kg (110–132 lb), 3 = 60–70 kg (132–154 lb), 4 = 70–80 kg (154–176 lb), 5 = 80–90 kg (176–198 lb), 6 = 90–100 kg (198–220 lb), 7 = 100–110 kg (220–242 lb), 8 = 110–120 kg (242–264 lb), 9 = 120–130 kg (264–286 lb), 10 = 130–140 kg (286–308 lb), 11 = over 140 kg (308 lb).

All things considered, how would you describe your health (1 = very unhealthy, 7 = very healthy).

Table 1 Summary statistics: women seeking donors All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life (1 = very unsatisfied, 7 = very satisfied).

References

Acker, J. M. (2013). The case for an unregulated private sperm donation market. UCLA Women’s Law Journal, 20, 1–38.

Alvard, M. S., & Gillespie, A. (2004). Good Lamalera whale hunters accrue reproductive benefits. Research in Economic Anthropology, 23, 225–247.

Andersson, M., & Iwasa, Y. (1996). Sexual selection. TREE, 11, 53–58.

Becker, G. (2000). The elusive embryo: How women and men approach new reproductive technologies. Berkley: University of California Press.

Becker, G., Butler, A., & Nachtigall, R. D. (2005). Resemblance talk: A challenge for parents whose children were conceived with donor gametes in the US. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 1300–1309.

Bossema, E. R., Janssens, P. M., Treucker, R. G., Landwehr, F., van Duinen, K., Nap, A. W., et al. (2014). An inventory of reasons for sperm donation in formal versus informal settings. Human Fertility, 17, 21–27.

Botwin, M. D., Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (1997). Personality and mate preferences: five factors in mate selection and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality, 65, 107–136.

Brewaeys, A. De, Bruyn, J. K., Louwe, L. A., & Helmerhorst, F. M. (2005). Anonymous or identity-registered sperm donors? A study of Dutch recipients’ choices. Human Reproduction, 20, 820–824.

Burr, J. (2009). Fear, fascination and the sperm donor as ‘abjection’ in interviews with heterosexual recipients of donor insemination. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31, 705–718.

Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Science, 12, 1–49.

Buss, D. M. (1995). Evolutionary psychology: A new paradigm for psychological science. Psychological Inquiry, 6, 1–30.

Buss, D. M., & Barnes, M. (1986). Preferences in human mate selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 559–570.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204–232.

Buss, D. M., Shackelford, T. K., Kirkpatrick, L. A., & Larsen, R. J. (2001). A half century of mate preferences: The cultural evolution of values. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 491–503.

Christensen, H. (1947). Student views on mate selection. Marriage and Family Living, 9, 85–88.

Cotton, S., Small, J., & Pomiankowski, A. (2006). Sexual selection and condition-dependent mate preferences. Current Biology, 16, R755–R765.

Daniels, K. (2007). Donor gametes: Anonymous or identified? Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 21, 113–128.

Daniels, K., Gillett, W., & Grace, V. (2009). Parental information sharing with donor insemination conceived offspring: A follow-up study. Human Reproduction, 24, 1099–1105.

Darwin, C. (1872). The origin of species. London: John Murray.

Dokoupil, T. (2011). ‘Free sperm donors’ and the women who want them. Newsweek, Oct., 2, 2011.

Elinder, M., & Erixson, O. (2012). Gender, social norms, and survival in maritime disasters. PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America), 109, 13220–13224.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness. Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Fisher, R. A. (1958). The genetical theory of natural selection. New York: Dover Publications.

Flinn, M. V. (1986). Correlates of reproductive success in a Caribbean village. Human Ecology, 14, 225–243.

Frey, B. S., Savage, D. A., & Torgler, B. (2010). Interaction of natural survival instincts and internalized social norms exploring the Titanic and Lusitania disasters. PNAS ( Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America), 107, 4862–4865.

Gangestad, S. W., & Buss, D. M. (1993). Pathogen prevalence and human mate preferences. Ethology and Sociobiology, 14, 89–96.

Gangestad, S. W., Thornhill, R., & Yeo, R. A. (1994). Facial attractiveness, developmental stability, and fluctuating asymmetry. Ethology and Sociobiology, 15(2), 73–85.

Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4, 26–42.

Gurven, M., Allen-Arave, W., Hill, K., & Hurtado, M. (2000). “It’s a wonderful life”: Signaling generosity among the Ache of Paraguay. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 263–282.

Hargreaves, K. (2006). Constructing families and kinship through donor insemination. Sociology of Health & Illness, 28, 261–283.

Harris, J. R. (1995). Where is the child’s environment? A group socialization theory of development. Psychological Review, 102(3), 458.

Harris, J. R. (2011). The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Hill, R. (1945). Campus values in mate selection. Journal of Home Economics, 37, 554–558.

Kenrick, D. T., Sadalla, E. K., Groth, G., & Trost, M. R. (1990). Evolution, traits, and the stages of human courtship: Qualifying the parental investment model. Journal of Personality, 58, 97–116.

Kirkman, M. (2004). Genetic connection and relationships in narratives of donor-assisted conception. Australian Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society, 2, 1–20.

Kirkpatrick, M., & Ryan, M. J. (1991). The evolution of mating preferences and the paradox of the lek. Nature, 350, 33–38.

Klock, S. C., Jacob, M. C., & Maier, D. (1996). A comparison of single and married recipients of donor insemination. Human Reproduction, 11, 2554–2557.

Lancaster, J. (1991). A feminist and evolutionary biologist looks at women. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 34, 1–11.

Lawrence, P. R., & Nohria, N. (2002). Driven: How human nature shapes our choices. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Leiblum, S. R., Palmer, M. G., & Spector, I. P. (1995). Non-traditional mothers: Single heterosexual/lesbian women and lesbian couples electing motherhood via donor insemination. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 16, 11–20.

Li, P. N., Bailey, J. M., Kenrick, D. T., & Linsenmeier, J. A. W. (2002). The necessities and luxuries of mate preferences: Testing the tradeoffs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 947–955.

Miller, G. F. (2007). Sexual selection for moral virtues. Quarterly Review of Biology, 82, 97–125.

Miller, G. F., & Todd, P. M. (1998). Mate choice turns cognitive. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2, 190–198.

Mulder, M. B. (1990). Kipsigis women’s preferences for wealthy men: Evidence for female choice in mammals? Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 27, 255–264.

Nordqvist, P. (2012). Origins and originators: Lesbian couples negotiating parental identities and sperm donor conception. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14, 297–311.

Pawłowski, B., & Dunbar, R. I. (1999). Impact of market value on human mate choice decisions. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 266(1416), 281–285.

Pérusse, D. (1993). Cultural and reproductive success in industrial societies: Testing the relationship at the proximate and ultimate levels. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16, 267–322.

Powers, E. A. (1971). Thirty years of research on ideal mate characteristics: What do we know? International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 1, 207–215.

Puts, D. A. (2010). Beauty and the beast: Mechanisms of sexual selection in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31, 157–175.

Riggs, D. W., & Russell, L. (2010). Characteristics of men willing to act as sperm donors in the context of identity-release legislation. Human Reproduction, 26, 266–272.

Rodino, I. S., Burton, P. J., & Sanders, K. A. (2011). Mating by proxy: A novel perspective to donor conception. Fertility and Sterility, 96, 998–1001.

Saucier, G. (1994). Mini-markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar big-five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 506–516.

Shapo, H. S. (2006). Assisted reproduction and the law: Disharmony on a divisive social issue. Northwestern University Law Review, 100, 465–480.

Scheib, J. E. (1994). Sperm donor selection and the psychology of female mate choice. Ethology and Sociobiology, 15, 113–129.

Scheib, J. E. (1997). Female choice in the context of donor insemination. In P. A. Gowaty (Ed.), Feminism and evolutionary biology: Boundaries, intersections and frontiers (pp. 489–504). New York: Chapman & Hall.

Scheib, J. E., Kristiansen, A., & Wara, A. (1997). A Norwegian note on sperm donor selection and the psychology of female mate choice. Evolution and Human Behavior, 18, 143–149.

Symons, D. (1980). Précis of the evolution of human sexuality. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3, 171–214.

Thorn, P., Katzorke, T., & Daniels, K. (2008). Semen donors in Germany: A study exploring motivations and attitudes. Human Reproduction, 23, 2415–2420.

Townsend, J. M. (1989). Mate selection criteria: A pilot study. Ethology and Sociobiology, 10, 241–253.

Trivers, R. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual selection and the descent of man 1871–1971 (pp. 136–179). Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company.

Trivers, R. (2002). Natural selection and social theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Waynforth, D., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1995). Conditional mate choice strategies in humans: evidence from’Lonely Hearts’ advertisements. Behaviour, 755–779.

Welling, L. L. M., DeBruine, L. M., Little, A. C., & Jones, B. C. (2009). Extraversion predicts individual differences in women’s face preferences. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 996–998.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from the Australian Research Council (FT110100463).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are thankful to the editor and two reviewers for their valuable comments and to David A. Savage for providing valuable feedback when developing the survey.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 5.

Our Big Five questionnaire, taken from Saucier’s (1994) work on the ‘mini-marker’, is a 36-item condensed version of Goldberg’s (1992) robust set of 100 markers for Big Five factor analysis. In our version, adjectives with a negative connotation were reversed (designated by the symbol R), so that the numerical value for all answers reflected the same low to high scale. To ascertain each participant’s numerical score for each factor, responses were aggregated on each factor and then averaged based on the number of questions on each. The extraversion factor contained one more question (8 in total) than the other four (each with 7).

The five factors were aggregated from the following scale items: Factor 1: Extraversion

-

Talkative

-

Withdrawn (R)

-

Bashful

-

Quiet (R)

-

Extroverted

-

Shy (R)

-

Enthusiastic

-

Lively

Factor 2: Agreeableness

-

Sympathetic

-

Harsh (R)

-

Kind

-

Cooperative

-

Cold (R)

-

Warm

-

Selfish (R)

Factor 3: Conscientiousness

-

Orderly

-

Systematic

-

Inefficient (R)

-

Sloppy (R)

-

Disorganised (R)

-

Efficient

-

Careless (R)

Factor 4: Emotional Stability (Neuroticism)

-

Envious (R)

-

Moody (R)

-

Touchy (R)

-

Jealous (R)

-

Temperamental (R)

-

Fretful (R)

-

Calm

Factor 5: Openness (Intellect and/or Imagination)

-

Deep

-

Philosophical

-

Creative

-

Intellectual

-

Complex

-

Imaginative

-

Traditional

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whyte, S., Torgler, B. Selection criteria in the search for a sperm donor: behavioural traits versus physical appearance. J Bioecon 17, 151–171 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-014-9193-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-014-9193-9

Keywords

- Online sperm donor market

- Informal donation

- Donation recipients mating preferences

- Mate choice

- Sexual selection

- Evolutionary psychology