Abstract

This paper employs geographic information systems (GIS) to analyze the relationship between environmental context and social inequality. Using recent archaeological data from the political center of the Inka Empire (Cuzco, Peru), it investigates how material and spatial boundaries embed social differences within the environment at both local and regional scales. In doing so, the paper moves beyond conventional archaeological GIS approaches that treat the environment as a unitary phenomenon. It develops a methodological and theoretical framework for the examination of a political landscape—the distinct spaces and materials that differentially shape people’s social experience and perception of their environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Archaeologists have long focused on how ancient people’s perception and use of the environment influenced their social and economic organization. Geographic information systems (GIS) has recently become the principal analytical tool through which archaeologists examine human–environmental relationships (e.g., Aldenderfer and Maschner 1996; Arkush 2009; Bauer et al. 2004; Casana 2003; Casana and Cothren 2008; Chapman 2006; Conolly and Lake 2006; Howey 2007; Kosiba 2011; Lake and Woodman 2003; Llobera 2003, 2007; Lock 2000; Spikens 2000; Wernke 2007; Wernke and Guerra Santander 2010; Williams and Nash 2006). In applying GIS, archaeologists have tested innovative hypotheses about human environmental interaction, from phenomenological questions of how past social actors perceived the cultural meaning of particular places to political economic assessments of how past societies managed specific resources.

Despite the expanded analytical perspective afforded by archaeological GIS research, many studies are rooted in theoretical assumptions about the environment that limit our view of past social contexts. That is, archaeological GIS analyses often treat the environment as a singular, independent variable—an a priori setting for social action, or the root of cultural meanings and values. GIS analyses often assume commonalities among past social actors’ use, experience, and perception of the environment. Fewer archaeological studies concentrate on how people of different social stations may experience and perceive the same physical environment in remarkably distinct ways (cf. Fitzjohn 2007; Kwan 2002). Consequently, GIS is rarely employed to examine how the environment is itself a social and political product.

This paper explores GIS as a tool to examine how constructed environmental differences—barriers, boundaries, and marked places—engender distinct spatial practices and perceptions. By analyzing recent archaeological data from the political center of the Inka Empire (Cuzco, Peru), we introduce a GIS methodology that assesses how power relations shape the environment, and by implication, actors’ engagements with the land, particular places, and a broader social geography. Our approach defines the environment less as an independent phenomenon that comprises systemic economic or cultural values, and more as a true landscape, a “geography of difference” that is subject to unpredictable variations, social erosions, and political fault lines (Harvey 1996). Considered as such, an environment is partly a political process, an ongoing project that is realized in the very spaces through which different people perceive themselves and their world. In attending to these themes, we seek to contribute to an ongoing dialogue about the application, epistemology, and theoretical relevance of GIS research in archaeology, and more generally (e.g., Bodenhamer et al. 2010; Conolly and Lake 2006; Kvamme 1992, 1999; van Leusen 2002; Wheatley and Gillings 2000; Wright et al. 1997).

Contrasting Landscapes Within Archaeological GIS Analyses

Archaeological GIS studies employ sharply contrasting theoretical approaches to landscapes and environments (see Anschuetz et al. 2001, Ashmore and Knapp 1999, David and Thomas 2010; Smith 2003 for recent reviews of landscape archaeology). Some archaeologists use GIS to examine systemic cultural adaptations to natural climatic and geographic conditions, frequently framing landscapes or environments as terrains of social or economic resources (e.g., Anderson and Gillam 2000; Jones 2006; Wescott and Brandon 2000). Others have applied GIS methodologies that concentrate instead on how societies assign cultural significance to their environment, treating landscape as a topography of meaning and memory (e.g., Chapman 2003; Llobera 1996, 2001).

We term these approaches “econometric” and “interpretative,” respectively (see also Wheatley 1993). In the following review, we suggest that, notwithstanding their theoretical variance, these approaches constrain our understanding of past human–environmental interaction in strikingly similar ways. Below we use the term “environment” to refer to the physical—constructed, geological, and topographic—attributes of a given area. We employ the term “landscape” to refer to the mélange of places, practices, and concepts through which people experience and perceive their environment.

Econometric Approach

Econometric archaeological studies focus on how societies are organized around the distribution of economic resources and land types. Such analyses often draw upon cultural ecological theories that view the social landscape as a systemic and economizing response to a natural physical environment. The environment is examined at a macro-scale, and thus settlement patterns and site locations are often evaluated relative to general ecological, topographic or economic variables. These studies generally describe humans as rational actors who optimize their livelihood by maximizing socioeconomic “gains” and minimizing socioeconomic “costs.”

In many econometric GIS analyses, socioeconomic gains and costs are calculated through consideration of the physical attributes of land and the energy capacity of human or animal bodies. For instance, different kinds of “cost surface analyses” are often used to identify the “optimal” path that people take from one place to another (e.g., Anderson and Gillam 2000; Gaffney and Stančič 1991; Harris 2000; van Leusen 2002; White and Surface-Evans 2012; Whitley and Hicks 2003). In conducting such analyses, researchers assign particular “cost values” to cells of a raster map (see Douglas 1994 for a non-archaeological rendering). Cost values typically refer to the slope of terrain and cumulative distance between locations. A string of cost values constitutes a cost distance. Cost distances are used to delineate pathways (Anderson and Gillam 2000), and/or estimate prehistoric territorial boundaries (e.g., Hare 2004).Footnote 1 The results of these analyses are based upon the premise that any human actor within a given regional context would take the path that minimizes their energy expenditure and transportation costs.

Similar theoretical premises often underpin GIS analyses of relationships between settlement patterns, site locations, and economic resources (Lock and Harris 2006). Archaeologists frequently use GIS to predict site locations relative to hydrology, soil types, vegetation, slope, and/or potential agricultural productivity (e.g., Brandt et al. 1992; Duncan and Beckman 2000; Hunt 1992; Kohler et al. 2000; Mehrer and Wescott 2006; Wescott and Brandon 2000). They identify relationships between regional site types and environmental variables by modeling catchment areas, evaluating optimal-foraging behavior, and modeling prehistoric pathways (e.g., Limp 1991; Madry and Rakos 1996; Saile 1997). Considering long-term environmental dynamics, researchers employ cultural ecological perspectives, GIS, and related statistical applications to understand relationships between key environmental and social variables, such as population pressure and agricultural productivity (e.g., Murtha 2009; Varien et al. 2007). Some recent applications emphasize dialectical human–environmental relations, especially anthropogenic contributions to environmental processes (e.g., Fisher 2005; Fisher and Feinman 2005).

GIS viewshed analyses are used in econometric approaches to assess how the visibility of environmental features might have benefited a social group by allowing people to better monitor game, supervise agricultural fields, and/or oversee important spaces (Krist and Brown 1994; Madry and Crumley 1990; Lock and Harris 1996; Maschner 1996). Sites with larger viewsheds or lines-of-sight to other settlements are often considered more defensible (e.g., Gaffney and Stančič 1991; Jones 2006). In these applications, site location is interpreted to be the product of a systemic decision-making process that seeks to best manage and/or monitor a local environment.

By delineating the contours of regional environments, econometric approaches offer sound foundational evidence that may be tested with additional archaeological data. Such approaches often provide crucial data for the investigation of regional settlement systems, land use practices, and historical ecology. Moreover, they are essential to the site location efforts of many cultural resource management projects. Nevertheless, anthropologists have critiqued these approaches on the grounds that their narrow economic focus provides only a faint rendering of the particular political agendas and cultural values that often underpin the production of societies and their settlement systems (e.g. Smith 2003). We add that the overall analytical utility of these applications is somewhat limited due to the highly generalized units of analysis that they employ. Econometric GIS approaches conceptualize the environment as a singular entity reducible to economic values—a generalized “region” consisting of discernable resources and “use-values.” They assume that researchers can quantify and generalize the energy capacity of the human body, and classify human motivations, regardless of cultural, historical, or political conditions (cf. van Leusen 2002). Furthermore, these analyses often take archaeological “sites” to be units of analysis and then produce a schematic macro-scale rendering of relationships between “sites” (often categorized by size alone) and regional resources. In so doing, the econometric approach obscures the differences in spaces and practices that might have socially defined these sites and their inhabitants. Thus, when applied in GIS analyses without additional archaeological data, econometric approaches frequently assume that all people within a region would have approached their environment in similar economizing ways.

Interpretive Approach

In response to anthropological critiques of such economizing logics, numerous archaeologists have employed interpretative or phenomenological approaches to understand the role of subjective cultural perception in human–environment interaction. These approaches are largely grounded in postmodern geographical theories and/or post-processual archaeological accounts that define landscape as a cultural system of meanings encoded within places and objects (e.g., Bender 1998; Feld and Basso 1996; Gosden 2001; Tilley 1994, 2004; Tuan 1989, 2000). They hold that people affectively engage with their environment and reproduce cultural meanings through their bodily experience and perception of places. Contrasting the objective and economizing gaze of the econometric approach, interpretative studies are typically subject oriented, hermeneutic, and inductive.

Interpretive approaches in archaeology reflect a broader trend in the social sciences and the humanities. Geographers have argued that the abstract and reductive land attributes of GIS analyses obscure local cultural understandings of the environment and fail to capture how social differences and values shape people’s spatial perceptions (e.g., Hanson 2002; Joly et al. 2009; McLafferty 2002; Rundstrom 1995). Such researchers advocate a more humanistic, locally oriented, and interpretative approach to social geography and history (see examples in Bodenhamer et al. 2010).

The vast majority of archaeological interpretative GIS analyses attempt to replicate past sociocultural perceptions of the environment by modeling the visibility of places and land attributes (Gaffney et al. 1996; Llobera 1996, 2000; Maschner 1996; Pollard and Gillings 1998; Ruggles and Medyckyj-Scott 1996; Wheatley 1993, 1995, 1996). For instance, in an often-cited early study, Fisher et al. (1997) documented how Bronze Age cairns on the Isle of Mull (Scotland) consistently afford greater visibility of the sea than other locales on the island. They interpreted these data as evidence that the ocean held particular cultural significance for the cairns’ producers (for similar interpretations, see Cummings 2003; Cummings and Whittle 2003). Similarly, researchers frequently use GIS to examine how the intervisibility of sites and features undergirded local people’s perception of their social relation to other people and places and to their own past. Chapman (2003), for example, demonstrated visual relationships among Neolithic monuments in the Great Wold Valley of England that suggest later monuments were deliberately constructed to provide visibility to earlier monuments, thereby creating an experiential and perceptual link to the past.

Archaeologists who apply an interpretative approach assert that the visual salience of select environmental features proves instrumental in shaping broader systemic cultural perceptions and social values. Such interpretive GIS analyses thus provide crucial preliminary data that may be tested with more robust archaeological and ethnohistorical information. However, archaeologists have outlined several theoretical problems associated with interpretative and phenomenological approaches, primarily calling attention to how these theoretical perspectives cannot sufficiently account for historical change or social agency within a given context (e.g., Brück 2005). Moreover, researchers have emphasized the empirical and methodological limitations of the GIS techniques typically employed within interpretative studies, particularly visibility analysis (see Fontijn 2007; Lake and Woodman 2003; Llobera 2007; Tschan et al. 2000; Wheatley and Gillings 2000). For instance, the data used for viewshed analyses are often too coarse to replicate human perception. Coarser datasets (30–90-m resolution) can be sufficient for macro-scale analysis, but finer resolution data (1–15-m resolution) are necessary for more detailed studies (see also Madry and Rakos 1996; Ruggles and Medyckyj-Scott 1996). Viewshed analyses also frequently presume that ancient land had the same physical, topographic, or vegetative attributes as those used for the construction of a digital elevation model (Lock and Harris 1996; Wheatley and Gillings 2000; cf. Tschan et al. 2000; Winterbottom and Long 2006). Also, many of these analyses presuppose that computationally visible raster cells “stood out,” thereby equating their digital visibility with their actual visibility (see similar critique in Llobera 2007; Ogburn 2006).

We build upon these critiques by noting that interpretative GIS studies often take archaeological “sites” (places and prominences) and their “region” to be basic units of analysis, therefore homogenizing a range of subjective experiences within and among the places considered. That is, the approach often assumes a general and systemic cultural relationship between the high visibility and the high significance of a place, regardless of political and historical particularities. In so doing, interpretative approaches tend to study the cultural perception of environment at a systemic level, and do not take into account how power relations might work to fracture local perspectives of the environment. In consequence, subjective differences in experience and perception are obscured by analyses that chiefly consider how a generalized “cultural subject” would have perceived the environment.

Political Landscapes Approach

Ultimately, both of the aforementioned theoretical approaches falter on the same ground. Econometric and interpretative approaches alike generalize human behavior by assuming that people in a given region would have (economically or culturally) valued an environment in the same systemic ways, regardless of differences in subjectivity, political agenda, or social station. Econometric studies generalize behavior by reducing human engagement with the environment to either homogenous energy expenditure or abstract economic calculations of utility. In this model, human social actions are conditioned by a rational assessment of how the environment may be used or traversed in ways that maximize economic gains while limiting potential costs or risks. The interpretative approach generalizes behavior by reducing human engagement with the environment to abstract and homogenous sensory perception. In this model, social actors’ engagement with the environment is largely driven by structures of meaning that are deeply embedded within landforms and places. Both approaches empirically reify their generalizations by focusing on the “site” and the “region” as units of analysis. People, and the material differences that constitute a social world, are lost within accounts that describe landscapes only in abstract, reductive terms of sites and regions.

The shortcomings of these approaches emphasize the need for an alternative theoretical foundation for GIS analyses, one that might better address the complicated agent-based and historical questions often posed by contemporary archaeologists (for novel solutions, see Howey 2007; Wernke 2007; Wernke and Guerra Santander 2010). Indeed, archaeologists and social theorists have recently eschewed approaches that treat space as a preexisting environmental backdrop, instead emphasizing how space is continually defined and redefined to further accentuate the social boundaries that underlie ideologies of political order (e.g., Alcock 2002; Harvey 1989, 1996; Kwan 2002; A. Smith 2003, 2004; M. Smith 2005). In an innovative study, Gold and Gujar (2002) explore the ecological degradation of what was once a lushly forested region in Sawar, Rajasthan. They underscore how the intentional—political and historically dynamic—practices of deforestation redefined this environment and thereby created a new framework of mourning and loss through which people now perceive their relationships to the past, social authorities, and the land itself. Here, politics is understood through conceptual boundaries of past/present and ideal/real that are etched into the land. Also, in a sociological study of Los Angeles, Davis (1990) examines how deeply entrenched social boundaries throughout the city dispose urban dwellers and visitors to perceive and experience the same concrete and neon environment in remarkably different ways. Finally, Moore’s (1996a, b) analysis of space, power, and proxemics in ancient Peru illustrates how archaeologists might examine social and spatial differences by attending to the ways that public architecture bolsters a political ideology by directing and constraining people’s perception and movement (cf. Swenson 2006, 2007).

In recent research, archaeologists have sought to overcome the reductive constraints of econometric and interpretive GIS approaches by examining the social boundaries, barriers, and differences that constitute ancient landscapes (e.g., Bauer 2011; Johansen 2011; Kosiba 2011; Lindsay 2011; Rizvi 2011; Wernke 2007). Wernke and Whitmore’s (2009) comprehensive statistical and GIS analysis of historical, archaeological data, ethnographic, and environmental data reveals significant inter and intra-community social differences in household consumption, nutrition and land wealth during the early Colonial period in the Colca Valley, Peru. Moreover, Arkush (2005, 2009) employs GIS to examine how social and political boundaries were defined and defended in the pre-Inka (Late Intermediate Period (LIP)) northern Titicaca Basin of Peru. Arkush’s (2009: 207–209) viewshed and line of sight analysis of LIP hilltop sites (pukaras) reveals how imperial Inka accounts of powerful, centralized polities (señorios) within this area do not accord with regional archaeological evidence for a highly localized and politically fragmented landscape—a geography characterized by claims to locality and social difference (cf. Kosiba 2011).

These examples remind us that the cultural or political economic “regions” that archaeologists study are historically contingent, social, and political constructs. In fact, a “region” only obtains an appearance of territorial coherence through the instantiation of clear social (and inherently spatial) boundaries—urban/rural, public/private, ceremonial/domestic (e.g., Alonso 1994; Kosiba 2010: 306–307). Such boundaries are rooted in a geography of difference (Harvey 1996), a politicized material environment constituted by neatly defined and systematically demarcated neighborhoods, work areas, public spaces, natural resources, elite properties and slums. Through the assembly of such a spatial and social order, a particular perspective on environmental and social difference comes to appear as natural, shaping the practices and places of everyday life. That is, often the political project is to design an environment in which overtly social categories and boundaries seem to be inherent properties of places and spaces, and their organization. To understand a regional environment, then, is to map a political landscape constituted by social categories and spatial boundaries that influence and guide how people perceive their surroundings.

Our case study exemplifies one way that archaeologists may employ GIS to investigate such a political landscape. Using recent archaeological data from the Inka capital in Cuzco, Peru, we investigate how an Inka imperial territory was manifested through the production of formal spaces designed to restrict movement and direct perception, thereby cultivating in local people particular bodily dispositions and spatial practices constitutive of a definitively Inka model of social order. The example demonstrates how GIS might be used to uncover the social and physical differences that constituted past political landscapes.

Case Study: Spatial Practices Within the Inka Imperial Capital (Cuzco, Peru)

Throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Inkas built the largest empire in the indigenous Americas (D’Altroy 2002). As with many expansionary states, Inka imperial power was rooted in rigid class distinctions and strictly defined categories of social difference (Patterson 1985, 1992; Silverblatt 1988). Indeed, Inka governance was undergirded by a theocratic claim that cast the Inkas as divine caretakers of the social and natural world—the sole group possessing the otherworldly transformative power to cultivate order throughout what was claimed to be an otherwise chaotic Andean landscape (Bauer 1996; Kolata 1996; Kosiba 2010; Ramírez 2005; Urton 1999).

The Inkas sought to realize their vision of social order by sharply defining people, places, and things. Ethnohistorical sources reveal how Inka sumptuary laws and restrictions encoded and marked imperial subjects and authorities. Inka elites wore striking hairstyles, earspools, and fine clothing that defined them as otherworldly and divine personages (Acosta 1954 [1590]: 193; Betanzos 1968 [1551]: 48; Cobo 1990 [1653]: 208; Murúa 1962–1964 [1590]: Bk. II, Ch. 3, pp. 34–35). Their resplendent litters, boisterous processions, and elaborate seats (tianas) were meant to convey an impression of the highest authority within the Andes (Garcilaso 1965 [1605]: Bk. VI, Ch. 1; Guaman Poma 1980 [1615]: 422; Santillán 1968 [1563]: 108; see also Cummins 1998: 109; Ramírez 2005: 166). Inka elite spaces were hallowed grounds. Whether the august royal enclosures of the Inka capital at Cuzco (e.g., Betanzos 1968 [1551]: 49), or walled Inka estates and religious sites, access to elite and courtly spaces was often restricted to the privileged, distinguished classes (see examples in Bauer and Stanish 2001; Hyslop 1990; Kosiba 2010; Morris and Santillana 2007).

On the other side of the social scale, an Inka commoner’s life entailed stern limitations and social boundaries. Inka subjects were often moved or restricted to specific settlement enclaves and state farms (e.g., Cobo 1990 [1653]: 194, 196; D’Altroy 2001b: 216; DeMarrais 2001: 141; La Lone and La Lone 1987; Rowe 1982; Wachtel 1982). They were distinguished by ‘typical’ practices and dress, both of which conformed to a state-mandated, essential socio-ethnic identity (e.g., Cobo 1990 [1653]: 196–197, 206; Garcilaso 1965 [1605]: Bk. I, Ch. 22; Las Casas 1939 [1550]: 120). Their community’s lands were partitioned, categorized, and appropriated. Indeed, upon incorporating a region the Inkas redefined the socioeconomic resources of once-autonomous peoples by sharply delineating which lands and animals were to be used by the local community and which were to be reserved for the state and the imperial religion (e.g. Acosta 1954 [1590]: 195; Garcilaso 1965 [1605]: Bk. V, Ch. 1; Polo de Ondegardo 1916 [1571]: 59–61; see also D’Altroy 2001b: 214–215; La Lone and La Lone 1987: 48). The Inkas limited their subjects’ possession of valued items, regulated their movement between areas, and relegated their major ceremonies to select, state-controlled spaces (e.g. Las Casas 1939 [1550]: 126; de Murúa 1962–1964 [1590]: Bk. II, Ch. 13, 62–63; see also Coben 2006; D’Altroy 1992, 1994; D’Altroy and Earle 1985; Hyslop 1984).

Archaeological research in the Cuzco region has focused on how the Inkas built an environment that supported and symbolized their power. Systematic surveys have demonstrated that the Inkas first attempted to support their political economy and control local populations by establishing an integrated settlement system overseen by select elites within nested administrative sites (e.g., Bauer 2004; Covey 2006; Kosiba 2010). More localized studies have revealed the symbolic power embedded within the towering edifices and intricately shaped environmental features of the Inkas’ Cuzco region imperial heartland (e.g., Acuto 2005; McEwan and van de Guchte 1992; Niles 1999). The growing body of research within the Cuzco region further enhances our knowledge of the general spaces and sites that exemplified and expressed Inka power. Too often, though, archaeological studies infer political meaning or function from site types alone: for example, large monuments and administrative spaces are proposed to be the bedrock of an Inka social geography. But the privileging of such state spaces reveals only one side of Inka Cuzco. Our intention is to complement previous studies by mapping the overall spatial organization of an Inka political landscape—the integrated network of spaces and boundaries through which both Inka subjects and authorities engaged with their environment and perceived their social roles relative to Inka power.

In this case study, we use GIS to examine how distinct kinds of Inka spaces and architectural forms engendered different social practices and perceptions within the Ollantaytambo area—an essential part of Cuzco, the Inka capital (Fig. 1). We concentrate less on the political economic function or symbolic meaning of Inka buildings, and more upon how Inka spaces themselves created material and social boundaries that differentially shaped people’s social action, experience, and perception. Data presented here are derived from an intensive multi-scalar archaeological survey and excavation project directed by Kosiba in the Ollantaytambo area (Wat’a Archaeological Project (WAP) 2005–2009). The WAP included: (1) a full-coverage pedestrian survey of a 200-km2 area near Cuzco that crosscuts several ecological zones and contains many archaeological sites that have been characterized as seats of pre-Inka and Inka political authority (Kendall et al. 1992, Niles 1980; Rowe 1944), (2) mapping, intensive surface collections, and architectural studies at pre-Inka and Inka sites, and (3) excavations at Wat’a, a pre-Inka village and shrine that was converted into an Inka fortress and ceremonial center (for a description of the project’s methods, see Kosiba 2010: 40–56).

Our GIS analysis examines whether and how different kinds of Inka residential buildings—categorized according to degrees of architectural elaboration—correspond to different kinds of environmental contexts.Footnote 2 We concentrate on residential spaces because researchers have long established that quantitative and qualitative differences in Inka residential architecture are linked to socio-political status differences (e.g., Kendall 1976, 1985; Niles 1980, 1987, 1999). Our study focuses on the standard and ubiquitous rectangular Inka buildings that were often used as houses, while specifically excluding architectural types like elongated halls (kallankas), storage buildings (qolqas), and the administrative/ritual purpose buildings that often flank plaza areas. By using building types as units of analysis, we avoid treating “sites” as proxies for regional differences in social status or administrative function, and instead investigate whether and how certain environmental contexts worked to differentiate social practices and positions.

Macro-scale

The WAP survey data provide analytical entrée into the spatial and social organization of the Ollantaytambo area. The survey documented 187 Inka period sites (Fig. 2), arranged in localized clusters within the narrow valleys of the region. Roads and shrines link these settlement clusters, ultimately connecting them to Ollantaytambo, a massive and monumental Inka city (Kosiba 2010; Protzen 1991).

A map of Inka period settlement distribution throughout the Ollantaytambo area. The map illustrates Inka site sizes relative to the percentage of surface-level-decorated serving vessels at each site while also showing the location of Inka sites relative to potential maize production terrain (MPT). Sites smaller than 0.5 ha were excluded from the map. Names correspond to the settlements mentioned throughout the article

Several (39) of the Inka sites contain well-preserved Inka architecture, including residential structures bearing stylistic features and construction techniques that conform to the Inka architectural canon (Table 1).Footnote 3 To constitute our sample of residential spaces, we established three architecture categories based on notable qualitative and statistically significant quantitative differences in style, embellishment, materials, construction techniques, and by implication, estimated labor expended (see Table 2; Fig. 3). Due to differential preservation conditions of building walls throughout the sample, we estimated percentages of qualitative and stylistic features per building type.

The architectural types considered in this study include: largely unadorned and standard Inka commoner houses that do not typically include shaped stones or quoins ((R1) top); houses featuring more than two kinds of stylistic elaboration, such as the fitted quoins and niches pictured here ((R2) middle); massive structures that exhibit multiple forms of stylistic elaboration, such as the niches, fitted stone, worked masonry, stretchers (bottom right), and quoins pictured here ((R3) bottom)

Rank1 structures (R1) are standard buildings with very little elaboration. Some R1 building interior walls (∼24%) contain small niches, but such buildings do not exhibit any other stylistic features. The rear walls of R1 buildings are often flush with a terrace wall. Based on recent excavations and analyses conducted within these and similar buildings (Cuba Peña 2003, 2004; Kosiba 2010; Niles 1987), these structures are probably commoner residential spaces. Rank2 structures (R2) are a bit larger, exhibit two or more kinds of stylistic embellishment, and are built upon raised platforms or terraces. R2 buildings frequently contain niches within their interior walls (∼58%), and quoins that make up their doorframes and exterior corners (∼90%). Some R2 building walls (∼43%) contain stretchers and fitted stone, but very few of their walls contain worked stone. It is evident that some of these buildings’ walls were plastered. Excavations and surface collections in similar types of Cuzco area Inka buildings have yielded materials that suggest that these are most likely elite residential structures (Cuba Peña 2003, 2004; Kosiba 2010). Rank3 (R3) structures are the largest and most elaborate kind of Inka building. These structures typically contain three or more kinds of stylistic embellishment. All R3 buildings contain niches and quoins, while a majority (∼79%) of the sample contains stretchers and fitted stone. R3 buildings frequently contain worked stone, and it is evident that some of these buildings were covered in plaster and painted (typically red). Of the three architectural types, R3 building walls often have a shorter length to width ratio (∼1:1.2). R3 structures also sit on raised platforms or terraces. Excavations and analyses in comparable Inka buildings suggest that these are elite residential structures and/or administrative buildings (Covey 2006; Kendall 1996; Kosiba 2010; Niles 1987, 1999).

Our sample consists of 127 structures—three to five buildings selected from each of the 39 sites with preserved architecture. This sample is about 8% of the total number of Inka period buildings recorded within the WAP survey, an adequate representation of variability throughout the area. We employed a stratified random sampling technique. That is, we randomly chose structures from distinct strata (sectors or areas) within each site: higher and lower elevations, opposite sides, and/or discrete neighborhoods. Most of the sites are relatively small (<2 ha.), and the residential architecture is concentrated within a single zone. Thus, buildings within each site were most likely subject to similar site formation processes, and it is probable that the particular, contingent, and localized taphonomic environment of each site would have affected building preservation, rather than regional environmental processes. Given these conditions, we expect the general patterns uncovered by the macro-scale study to reflect the intention of the Inka period builders, rather than a bias resulting from differences in preservation or taphonomic processes. Further study of Inka architecture within the Cuzco area will greatly improve upon the foundational conclusions presented within this paper. Here, we compare architecture, surface collection data, environmental variables, and viewsheds of these residential architecture types. Our analysis identifies inter-site patterns for each architectural type and intra-site differences within settlements that contain more than one of these architectural types.

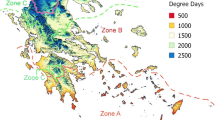

We first tested overall relationships between the architectural categories and their environmental setting, particularly their location near productive maize agricultural land and/or terraced maize fields. We expected R1 buildings to be situated in or near such lands since ethnohistorical accounts and recent archaeological data suggest that maize agricultural production and field maintenance practices largely defined the daily life of commoners (e.g., Bauer 2004: 95; Covey 2006; D’Altroy 1992, 2002: 266; Hastorf 1993; Hastorf 2001: 170–172; Murra 1973, 1980 [1956]: 12–13). Using remotely sensed data (ASTER GDEM and ASTER multi-spectral), GIS, and field observations, Kosiba (2010) characterized potential maize production terrain (MPT) as land that adheres to the minimal biological requirements of dry farming maize cultivation, most generally: land with less than a twenty-percent slope located at an altitude less than 3,500 m (see Gade 1975). MPT was also delineated based upon an examination of ASTER images (extraction of areas with soils containing high gypsum content, areas lacking water sources, and areas with high degrees of erosion), as well as detailed field observations, including both the documentation of current agricultural fields and informal interviews with contemporary farmers (see Kosiba 2010, 2011).

The analysis revealed that buildings of different architectural types were situated at varying distances to potential maize agricultural land. Reflecting a common trend in Inka site location, most (72%) of our sample structures are only a short walking distance (500 m) from either MPT or terrace systems (Fig. 2). Yet contrary to our expectations, R1 structures tend to be situated at a greater distance from agricultural lands (>500 m) than R2 or R3 structures. In comparing the standard (R1; n = 63) and more elaborate (R2–R3; n = 64) architectural styles, there is a significant difference in distance to agricultural land (t = −3.318; df = 125; sig. at the 0.001 alpha level) and distance to terrace systems (t = −3.841; df = 125; sig. at the 0.001 alpha level). More elaborate structures (R2–R3) are often situated directly within MPT (for example, 27.5% of R1 spaces, 58.8% of R2 spaces, and 51.7% of R3 spaces are situated within MPT).Footnote 4

This pattern is replicated in many settlements that contain one or more of the architectural types. Within the majority (10/15, 66.7%) of the sites that contain both R1 and more elaborate architectural types, R2–R3 structures are more commonly situated much closer to maize fields and terraces than R1 structures. For instance, at the site of Markaqocha, immense R3 structures are positioned in maize fields, next to a stream, approximately 200 m below the densely packed R1 house structures of the main ridge-top town (Kosiba 2010: 167). Similarly, larger R2 structures are located at the low margin of the Inka settlement at Paqpayoq, at the very edge of the maize terraces that link the village to the valley floor. These data thus suggest that more elaborate structures were often spatially connected to productive maize land while less elaborate structures were often functionally situated between higher elevation pastoral land and lower elevation maize agricultural terrain.

In addition to these locational differences, we assessed whether spaces and materials for ceremonial practices are more frequently associated with the more elaborate architectural types. The Inkas staked claims to their authority and performed state largesse by hosting theatrical feasts within plazas (e.g., Morris and Thompson 1985: 89–91; Ramírez 2005: 212–213). Special materials, such as finely decorated Inka polychrome serving vessels (plates and bowls) were essential components of these feasts (e.g., Bray 2000, 2003, 2009; D’Altroy 2001a). Given the importance of these ceremonies to the constitution of elite authority, we thus expected plaza spaces and polychrome ceramics—and the ceremonial practices that they constituted—to be significantly linked to the more elaborate architectural types.

Our analysis reveals a significant correlation between plaza spaces and R2–R3 architectural categories (t = −8.526; df = 62 (equal variance not assumed); sig. at the 0.001 alpha level). The surface collections uncovered higher densities of Inka polychrome ceramic types associated with these more elaborate architectural categories (t = −4.84; df = 125; sig. at the 0.001 alpha level).Footnote 5 Moreover, surface collections at the sites that contained both R1 and more elaborate architectural types revealed higher densities of Inka polychrome serving vessels in and around R2–R3 spaces, in comparison with R1 spaces. It is clear, then, that plazas and serving vessel sherds are more commonly associated with the more elaborate residential structures.

However, plazas are also associated with many (46.3%) R1 structures. And more than half (52.4%) of the R1 spaces also contain high percentages of Inka serving vessels. Thus, the data suggest that the different architectural types were largely defined by differences in perhaps the scale or frequency but not necessarily types of social practices.

These practices may have had different sociopolitical purposes depending on the kinds of spaces in which they were staged. We find that R3 buildings are more frequently associated with architectural elements suggesting restricted entry—walls, platform entryways, single-access pathways or formal doorways. In contrast, few R2 buildings and no R1 buildings are enclosed within walls, accessed through formally restrictive architecture, or entered through only a single pathway. In other words, the most elaborate buildings are often marked as exclusive and restricted-access spaces. This spatial exclusion may have heightened the social importance of events and activities associated with these structures (see below).

Our viewshed analysis tested whether the architectural categories correspond to differences in the visibility of surrounding spaces. Archaeologists have suggested that Inka administrative and ceremonial sites were positioned in places with greater visibility, and hence social perception, of the environment—whether to control resources and pathways, or to establish sight lines with mountain peaks, rock outcrops, lakes, and ancestral places (e.g., Acuto 2005). We thus expected the more elaborate architectural spaces to have broader viewsheds of the surrounding terrain.

To calculate viewsheds we used a central point and an additional four points located ∼20 m in each cardinal direction from the central point. Resultant viewsheds from these five points were combined to produce an estimated viewshed area for each given residential space. In addition, we ran viewsheds from the 28 plazas and compared them to the 127 sample spaces to gauge whether the plaza spaces were built in areas that afforded heightened visibility of the surrounding environment. Viewsheds for the residential architecture spaces were also compared with viewsheds from a randomly selected background sample of 60 points. Altogether, the analysis considered 1,075 individual viewsheds and 215 combined viewsheds.

The analysis shows that broader overall viewsheds do not always correspond to more elaborate architecture types or spaces (Table 3; Fig. 4). There is little difference in the viewshed area of residential spaces and plazas within the same sites, suggesting that plazas were not situated in loci that maximized visibility of adjacent areas. Contrary to our expectations, R1 sites have significantly greater potential visibility of their environs than the other two architecture categories (t = 3.009; df = 125; sig. at the 0.01 alpha level). Only the R1 spaces have broader viewsheds than our background sample points (t = 2.899; df = 121; sig at the 0.01 alpha level). There is not a significant difference between the overall viewsheds of all (R1–R3) spaces and the background sample points (t = 1.737; df = 185; sig. 0.084). There is not a significant difference between the overall viewsheds of the background sample points and R2 spaces (t = −0.297; df = 93; sig 0.767) or R3 spaces (t = 0.477; df = 87; sig. 0.634). In short, it does not seem as though the Inkas intentionally built their more elaborate structures in areas that afford greater visibility of the surrounding environment.

These graphs illustrate differences in the overall viewsheds from the architectural categories considered within the sample. The box plot (left) shows the mean, range, and outliers of viewsheds among the architectural categories, as well as the background (BG) sample. The means plot (right) shows the differences in viewshed means

However, we found that the location of the more elaborate residential types often affords greater visibility of specific environmental features. For instance, there are patterned relationships between R3 architectural types and the visibility of the glaciated mountain peaks (apus), which are especially important to local ceremonial practice in both ancient and contemporary Andean contexts (e.g., Allen 2002: 26; Williams and Nash 2006: 457). Although any mountain peak can be an apu, our analysis considers the differential perception of glaciated mountain peaks. Such peaks were most likely revered or attributed cultural importance since they were both water sources and salient environmental features. In our survey area, one or more glaciated peaks are visible from the majority (89.7%) of R3 spaces (in comparison, one or more glaciated peaks are visible from 57.1% of the R2 spaces and 51.9% of the R1 spaces). Moreover, R3 spaces are the only building types from which three or more glaciated peaks can be seen at once. These more elaborate Inka spaces and residences may have been perceived in terms of their immediate and more pronounced link to these mountains, a link that may have bolstered Inka elite claims to divine authority (cf. Williams and Nash 2006).

Similarly, it appears as though the more elaborate residential architecture types were positioned so as to maximize visibility of particular spaces and sites. We recorded the percentage of archaeological sites and monumental Inka structures that are visible within a 1-km radius from the R1–R3 structures of our sample. Percentages were calculated as the amount of visible sites relative to the amount of recorded or actual sites within the 1-km radius. Using these parameters, we found that a greater quantity of such “immediate sites” was visible from the more elaborate architectural spaces (R2–R3) than the commoner architectural types (t = 2.031; df = 116.8; sig. at 0.05 level, equal variances not assumed). Also, one or more Inka monumental sectors including R3 architecture or formal plazas are visible from the majority (84.6%) of R1 spaces, which suggests that it was important for civic or ceremonial architecture to be visible from the commoner residential spaces (one or more monumental spaces are visible from 52.8% of the R2 spaces and 37.9% of the R3 spaces). Hence, the more elaborate residential structures seem to be built in places that maximize surveillance of commoners’ residences. The commoner residences are situated within the shadows of Inka monumental spaces as if to enhance the presence of state authority within the daily lives of Inka subjects.

Also, the analysis revealed how social distinctions may have been grounded in the topography of the narrow valleys themselves. The settlement enclaves are located within tightly circumscribed slopes and basins that afford broad inter-site viewsheds, thus allowing for the resident of a single site to see multiple other settlements within the immediate area. For instance, ten or more immediate sites are visible from 74.2% of the spaces within our sample, with no significant difference in visibility among the architectural categories. This intervisibility at the local level may have fostered a sense of community, facilitated the integration of tasks, provided for (at least an appearance of) heightened security, and increased communication between residents of separate villages. In addition, it is notable that only a single glaciated peak (apu) is visible from the majority of spaces within each settlement enclave. These particular peaks would have framed the daily experience of the people inhabiting a particular area, and only that area, perhaps engendering a personal relationship between specific communities and environmental features, much like how local social groups often claim genealogical relations with mountain peaks in the contemporary Andes (Allen 2002; Bastien 1985).

Altogether, the regional analysis suggests patterned relations between the Inka residential architectural types and particular kinds of environmental settings, practices, and perceptions. More elaborate residential types appear to be spatially and symbolically linked to salient cultural and environmental features: productive maize land, glaciated peaks, and spaces for collective ceremony. The location and environmental context of these more elaborate residential spaces thus suggest that their occupants sought to establish privileged social and economic relations to valued aspects of their environment—perhaps to directly control or oversee specific lands. Conversely, the less elaborate architectural types are most often situated between the major socioeconomic production zones and typically have a direct visual relationship with one or more monumental spaces. Such architectural types appear to correspond to a commoner/worker social position defined by labor within different economic resource zones, and a subservient relationship to state-controlled spaces for ceremonial activity. Overall, the macro-scale analysis begins to reveal the contours of a landscape sharply defined by social and spatial boundaries and categories—physical impediments like the walls that surround R3 spaces, as well as compartmentalized environmental settings like the special locales within which many of the Inka elite seem to have dwelled. In order to further comprehend these social and spatial boundaries, we must inquire into how they were perceived and experienced by the people that inhabited them.

Micro-scale

The majority of settlements within our sample contain distinct and differentiated sectors: a patchwork of Inka residences, formal plazas, mortuary sectors, and agricultural terraces. But there are striking differences in the organization and demarcation of these spaces within different settlements. In the following analysis, we examine the spatial organization of two Inka period sites—Wat’a and Paqpayoq. We seek to understand how differences in the residential architecture of these sites corresponded to distinct spatial layouts, and by implication, how different kinds of spatial organization might have influenced the ways that people engaged with their local environment.

We focus on these settlements because they allow us to analyze architectural and organizational differences between Inka elite and commoner residential spaces. Wat’a is a relatively large (∼27 ha), partially fortified elite settlement and ceremonial site positioned on a ridge-top between maize agricultural land and a high-altitude pastoral plain (Figs. 5 and 6). Paqpayoq is a smaller (∼6 ha) commoner village situated on a gradual hillside near verdant maize agricultural land (Fig. 7).Footnote 6 The majority of residential structures within Wat’a are R2 or R3 buildings. Paqpayoq contains predominantly R1 buildings. Despite differences in residential architecture, the settlements are comparable in various ways. Both Wat’a and Paqpayoq contain similar kinds of spaces, such as mortuary sectors, plazas, storage structures, platforms, and discrete residential areas. At both sites, the WAP intensive surface collections found higher densities of Inka polychrome serving vessel fragments near plaza and mortuary sectors, suggesting that similar kinds of feasting and mortuary veneration practices were staged within specific spaces of these sites. Moreover, both Wat’a and Paqpayoq are Inka settlements built over preexisting pre-Inka sites. Architectural analysis, excavations, and radiocarbon dates suggest that Wat’a was quickly reconstructed during the early phases of the Inka period, in the mid fourteenth century (Kosiba 2010). Architectural analysis and stratigraphy (of looter’s pits) at Paqpayoq suggest that it was rebuilt in the mid to late fourteenth century. Since early Inka state formation in Cuzco was in part predicated upon the spatial reorganization of local settlements and landscapes (Covey 2006; Kosiba 2010, 2012), the study of these sites provides a glimpse of how the Inkas implanted a new social order by constructing new kinds of physical barriers and social spaces.

To examine these settlements, the WAP produced detailed maps of topography, standing architecture, and environmental features. The GIS analyses at Wat’a and Paqpayoq examine the Inka period architectural layout of these sites. Kosiba collected over 6,500 topographic points while mapping Wat’a and over 3,000 points while mapping Paqpayoq. Topographic points were taken at intervals of 2 m or less. Surface collection units (5-m radius) were set up throughout both sites using a stratified systematic unaligned sampling technique (see Orton 2000; Plog 1976). Looted areas, relatively steep slopes (>30°), and colluvial deposits were excluded from the sampling universes.

The resulting maps were compared with intensive surface collection, architectural, and excavation data. GIS was employed to analyze the surface-level distribution of artifacts and architectural types, potential pathways and intra-site viewsheds. In particular, we used detailed maps to consider the “depth” (Hillier and Hanson 1984) of ceremonial or political spaces like plazas and mortuary sectors. Depth refers to the quantity of spaces through which one must pass in order to access other spaces. To consider spatial access within each site, we added quantitative and qualitative dimensions to this study of depth, taking into account the number of windows or doorways that look onto a pathway, the number of intersections along a certain path, as well as the kinds of environmental features that one passes if traversing the site on a particular path (see Kaiser 2011). We also computed a series of viewsheds to gauge the degree to which the architecture and topography of each site affect the visibility of architectural features, ceremonial spaces and/or activity areas.

To conduct the intra-site viewsheds, topographic surfaces (a triangulated irregular network (TIN) and a digital elevation model (DEM)) of each site were generated from detailed mapping using a total station. The TIN surface was used to edit errant points and model terrace walls. Terraces and platforms were added to the TINs as hard breaklines. The TIN was then converted into a raster DEM. Architectural features were drawn as polygons, and then converted to raster features corresponding to feature heights. Building and wall heights were added to the architectural raster according to estimates and measurements made in the field: R1 and R2 buildings were attributed 2–3 m in height; R3 buildings were assigned 3–4 m in height; the perimeter wall at Wat’a was attributed 4–5 m in height; and tombs structures were allotted 1.5–2 m in height. These are conservative estimates since they do not take into account the effect of pitched rooftops. Using a map algebra function, the architectural-based raster values were then added to the topographic DEM (Fig. 8). We calculated viewsheds from 35 loci within Wat’a and 30 loci within Paqpayoq.Footnote 7 Sample points were taken in open spaces: house patios, platforms and plazas. Viewsheds from a central point and four additional points at a distance of 5 min each direction were combined to create a patched viewshed from each locus.

Wat’a

At Wat’a, architectural styles and forms demarcate distinct kinds of spaces. An immense wall divides the settlement into discrete residential areas. This wall was raised during the initial phases of Inka state formation, when the long-occupied political center and town at Wat’a was partially demolished and then rebuilt at a monumental, and definitively Inka, scale (Kosiba 2010). Preexisting buildings and terraces within Wat’a were converted into the foundations of Inka structures. The Inka period walls at Wat’a separate a commoner residential sector from a ceremonial sector and town. The walled space at Wat’a appears to be a fortified elite residential area, not unlike the castles of medieval Europe or Rajasthan, India. Intramural and extramural sectors are further distinguished by architectural styles. Archetypical commoner houses (R1) are evenly spaced upon the gradual rise outside of the wall. Within the wall, immense buildings (R3) are situated atop a series of raised platforms that confront the visitor along the principal pathway of the site. The main ceremonial spaces at Wat’a (the plaza and mortuary sector) are conspicuous in their monumentality. Their walls display recognizable symbols of Inka prestige, like double jamb doorways, double frame windows and trapezoidal niches (e.g., Gasparini and Margolies 1980; Kendall 1976; McEwan 1998; Niles 1987). Enormous buildings (R3) surround the plaza space at Wat’a, restricting its access and obscuring it from onlookers (see below), while two walls enclose the mortuary sector (Wilkapata). In short, intramural spaces are monumental and stylistically complex, while extramural spaces are simple and unadorned.

In addition to defining different sectors, the sheer walls and steep slopes of Wat’a would have limited movement to prescribed pathways. There are only two entrances within the site’s massive perimeter wall. Upon entering, a subject faces two pathways. These are the only pathways that allow a visitor or inhabitant to traverse the site. The pathways themselves constrain movement: as they cut through the site’s vertical terraces and precipitous rock outcrops, they require subjects to enter baffled doorways, ascend formal staircases, and enter multiple platforms in order to access the patchwork of enclosed spaces across Wat’a. The platforms are arranged like checkpoints en route to the site’s monumental plaza. Narrow ramps or stairs constrain access and egress to select points within each platform, while slowing the traffic of groups of people that might proceed to the plaza space. Additionally, doors and windows of R3 structures open onto the platforms, suggesting that people were monitored while crossing Wat’a. In stark contrast to the walled sector of Wat’a, houses within the extramural sector conform to the undulating terrain, creating a network of interlinked and integrated open spaces among structural terraces.

In considering the viewshed analyses within Wat’a, we see that the architecture and topography of Wat’a both directs and constrains one’s visibility of key spaces and environmental features. No point within Wat’a affords greater visibility of the entire settlement than any other. But different areas of the site seem to have been specifically elaborated in order to heighten social actors’ perception of particular spaces. For instance, a platform near the main entryway directs perception toward a tomb sector embedded in the site’s wall, as well as the Wilkapata tomb sector. In so doing, this platform establishes a connection to history and tradition, using a recognizable idiom to immediately underscore the deeply rooted power of this place and perhaps the people contained therein.

However, the primary ceremonial spaces of Wat’a are largely hidden from visibility. A person standing within the extramural domestic sector could not see the activities that took place within the intramural area (Fig. 9). While this person could have heard ceremonies occurring, and perhaps seen the smoke from fires, their visual perception of these events was prohibited, just as their entry was barred by the baffled entryways and controlled pathways of Wat’a. Most remarkably, the site’s ceremonial plaza is only visible once one has traversed the entire site—it is not visible from the central intramural pathway until one is within 100 m of the plaza’s edge (Fig. 10a, b). Likewise, the mortuary complex contained within Wilkapata is hidden from view by two high walls, even though the central prominence of Wilkapata can be seen from the majority of our sample loci (81.3%). A person standing in areas lower than sector Wilkapata could not see the activities that were occurring within this central area.

a Schematic 2D representations of viewsheds from Wat’a, including the viewshed sample loci (top); an example of the limited visibility to and from the plaza (middle); and an example the surveillance potential of intramural spaces at Wat’a (bottom). b Schematic 2D representations of viewsheds from Wat’a, including an example of limited visibility from many sample loci within the extramural residential sector (top); the point from the main pathway from which the plaza is first visible (middle); and an illustration of the surveillance potential of select platform spaces (bottom)

In addition, the viewsheds suggest that the spatial organization of Wat’a provides for surveillance of intra-site spaces and the surrounding terrain (Fig. 10a, b). Select platforms and buildings within Wat’a were situated in places that maximize visibility of pathways and open spaces outside of the site’s perimeter wall. There are several intramural platforms that provide general visibility of the extramural sector, as well as the area into which an incoming party would arrive before entering the site. Furthermore, there are three distinct intramural platforms that provide direct visibility of the Inka roads that ascend to Wat’a. From these points, an incoming party can easily be signaled or seen at a distance of over two kilometers.

In localities like Wat’a, physical boundaries are rigid and finite. Architecture and topography constrain movement, restrict access, and limit perception of different spaces. The intramural space is defined by an architecture of exclusivity that appears to declare at once the heightened social and political significance of particular places. In the Ollantaytambo area, we find a similar spatial layout at other Inka settlements that include many R2 and R3 residential structures. At the partially fortified town of Pumamarka, a cyclopean wall surrounds a cluster of monumental buildings, plazas, and elite baths (Fig. 11). This walled sector is architecturally distinct from the agglomeration of R1 and R2 structures that rest upon a hillside below. Internal plaza spaces are not visible until one is within them. Spaces within Pumamarka are controlled and compartmentalized, while pathways are restricted. Much like Wat’a, this was most likely the fortified residence of a local Inka lord (Niles 1980). Furthermore, the carved boulders, plazas and ornate structures of the cliffside site at Perolniyoq are not visible until one is within the center of the site. There is only one entrance to Perolniyoq, and internal pathways are limited by sheer rocks and imposing walls. The restricted access and visibility of the site and the private arrangement of the internal spaces also suggest that Perolniyoq was an elite residence or local palace. These places are both fortified and sanctified—their walls materialize claims to absolute authority and exclusivity.

Paqpayoq

In comparison, the spatial organization of Paqpayoq is far less rigidly defined than that of Wat’a. Paqpayoq’s architecture does not emplace physical or social boundaries or differentiate spaces. Instead, architectural styles unify the social space of the village. Residential spaces and terraces at Paqpayoq seamlessly morph into an agricultural complex, ultimately leading into a hillside tomb sector. Curving terraces are a common denominator that underlie and define these spaces of production and consumption, life and death (Fig. 7). Houses (R1) are spaced at regular intervals upon the terraces. Throughout the settlement, there are minimal differences in the stylistic elaboration of these houses—the only difference is that small rectangular structures are attached to some houses, implying storage at the household level. Small, rustic niches are observable within some of the buildings with preserved walls, suggesting that this kind of architectural adornment was common throughout the village. The only discernible buildings that vary from the architectural standard at Paqpayoq are the larger (R2) buildings that are situated near the plaza. But even though these buildings are larger, their architectural style is consistent with the rest of the site: they are made of the same materials and exhibit the same features as the R1 houses, thus extending the general architectural aesthetic of the village. The tomb sector is also architecturally uniform. It consists of individual tower tombs (chullpas), each of them exhibiting analogous orientations, dimensions, morphological attributes, platforms and doors.

Similar to Wat’a’s extramural sector, few architectural features constrain movement at Paqpayoq. Terraces within Paqpayoq are relatively small (an average height of 1.2 m) and can be accessed from a variety of openings and stairs. Houses at Paqpayoq often face away from pathways and are oriented toward internal patio spaces, a design that has been documented at other Inka commoner villages (e.g., Niles 1987: 28, 36). One is not required to pass through a house’s patio if walking across the settlement. Furthermore, Paqpayoq’s ceremonial spaces are relatively permeable. The plaza is accessible from several points. And although there are two R2 buildings near the plaza, they do not enclose the plaza space; rather, they flank one side of it, thus framing an open space that is physically and visually accessible. Likewise, there are no architectural barriers to the tomb sector. In fact, the only restricted spaces within Paqpayoq are the residential patios themselves, which, much like some household complexes in the contemporary Andes (e.g., Flores Ochoa 1968) are surrounded and enclosed by buildings.

The viewshed analyses of Paqpayoq reveal that additional dimensions of openness characterize this residential space (Fig. 12). There is no significant difference in the overall extent of viewsheds within Paqpayoq. But, distinct from Wat’a, there are remarkable similarities in what can be seen from the sample loci at Paqpayoq. Tombs within the mortuary sector can be seen from the majority of house group patios (87.5%) (Figs. 13 and 14a, b). The plaza is visible from most of the house group patios (78.6%) (Fig. 14a, b). One can see the plaza sector, or anyone entering it, from nearly any point within the site. Also, one can see the entire settlement from various loci. The mortuary sector provides broad visibility of the village (Fig. 14a). Only the interior patios of the house-building groups cannot be seen from the mortuary sector. Overall, the viewsheds emphasize visibility of mortuary and plaza sectors while constraining perception of individual house patios.

a Schematic 2D representations of viewsheds from Paqpayoq, including an example of the high visibility to and from the tomb sector (top) and an example of the high visibility to and from the plaza sector (bottom). b Examples of typical viewsheds from Paqpayoq house patios illustrating the potential visibility of plaza and tomb sectors from such household spaces

At Paqpayoq, there is little indication of a general surveillance framework. R2 structures do not allow for greater visibility of other spaces within the settlement, as would be expected if these R2 spaces housed elites who watched over the community. There is limited intervisibility between the patios of the house groups—typically, only 2–3 patios of other houses are visible from a single house patio.

But an Inka subject within the terraces or pathways of Paqpayoq could have seen and been seen from many spaces within the site. The only hindrance to movement or perception would perhaps have been one’s knowledge of or inclusion within the community. That is, the distinct boundaries of this village as a whole suggest that it was a sharply defined space. Due to the open sightlines and pathways of the village, a stranger entering Paqpayoq might have appeared just as conspicuously ‘out of place’ as one entering Wat’a. Thus, at Paqpayoq, an open spatiality would have accentuated the social proximity of community members while distancing them from outsiders.

In sum, the absence of physical boundaries at Paqpayoq most likely corresponded to a distinct kind of social practice and perception. The architecture and topography of Paqpayoq heightens a sense of inclusivity that orients people to the local community and accentuates the village as a whole while emphasizing distinctions between people from this particular village and another. This kind of spatial organization is also apparent at other settlements throughout the Ollantaytambo area, especially villages that contain high percentages of R1 architectural types. Within these sites, the arrangement of residential spaces may vary. However, our architectural analyses verifies that, by and large, settlements dominated by R1 architecture types replicate the kind of relatively open and permeable spatial layout exemplified by the extramural sector at Wat’a, or the dramatically open and highly permeable layout of the undulating terraces of Paqpayoq.

Discussion: Legible Boundaries and Inclusive and Exclusive Spaces

In comparing the micro-scale and macro-scale levels of analysis, we can begin to understand the key differences in spatial organization that assembled an Inka political landscape. Throughout the region, distinct kinds of residential spaces coincide with local differences in architectural and environmental design. Boundaries are evident within the spatial layout of some places while they are conspicuously absent in others. More elaborate residential structures are often situated in locales that afford physical and perceptual access to culturally salient environmental features: expansive plazas for collective ceremony, the snow-capped mountain peak deities that literally held invaluable sources of water, and the verdant maize fields that provided both subsistence and ceremonial foods. Conversely, less elaborate residences are most commonly located outside of the towering walls of monumental precincts, or within small villages. In short, the environment is molded in such a way so that places, practices, and perceptions corresponded to distinct, and qualitatively different, kinds of space.

Inka residential spaces are further defined through an architecture of exclusion. More elaborate residences are often situated within a rigid spatial layout meant to control movement, direct perception and heighten a sense of propriety and obeisance. Indeed, within the cyclopean walls of Wat’a, social actors are required to conform to the spatial layout of the site itself. Generally, pathways within the intramural space of Wat’a are restricted, and viewsheds reflect an architectural layout designed to foreground the exclusivity of ceremonial spaces. In contrast, the spatial organization of Paqpayoq emphasizes physical connections and linkages between buildings, tombs and agricultural terrace spaces. The permeable environmental design at Paqpayoq seems to emphasize the inclusion of community members within a tightly knit, planned spatial and social structure that stresses spatial (and perhaps social) homogeneity.

These kinds of Inka spatial organization and environmental design are not limited to the Ollantaytambo area, suggesting that the Inkas were particularly concerned with creating elite spaces that emphasized exclusion and commoner spaces that accentuated inclusion. For instance, the multiple perimeter walls, formal doorways and monumental buildings of P’isaq—an Inka royal estate within the eastern Vilcanota valley—restrict access and direct movement in a similar way to spaces within Wat’a. The culturally salient features of P’isaq are not visible until one is very close to them. The carved boulders and intricate fountains of the “Intiwatana” sector are enclosed within monumental structures, suggesting that such spaces were highly regulated and controlled (Angles Vargas 1970: 40–41; Hyslop 1984: 299). Distinct sectors of the site are connected only by a singular pathway, which is hewn into the exposed rock of the ridge top. A similar spatial layout is evident at the early Inka estate of Tipon, located in the Cuzco Valley. Gigantic terraces, elaborate fountains and revered rock outcrops can only be seen once one has climbed a formal Inka stairway, and they can only be accessed through discrete walled entryways, flanked by massive buildings. A feeling of panoptical surveillance is pervasive at Tipon: as one ascends and traverses its pathways, one is constantly walking beneath and in view of multiple platforms, patio spaces, and tomb sectors. The elite residential space of nearby Cuzco area sites is similarly restricted, limited in access, and hidden from view (Gasparini and Margolies 1980: 188–190; Niles and Batson 2007; Protzen 1991). Looking farther afield, we see this propensity to demarcate, define, and control space at monumental sites throughout the Inka domain (see Morris and Santillana 2007).

Furthermore, a permeable and homogenous spatial layout similar to Paqpayoq is evident at many planned Inka commoner villages throughout the Cuzco region. At Raqay Raqayniyoq in the Cuzco Basin, architecturally standard residential structures are arranged along a gradually sloping hillside, with several potential pathways between them (Niles 1987: 31–37). Our architectural measurements of 25 buildings at Raqay Raqayniyoq are remarkably similar to R1 structures within the Ollantaytambo area, suggesting that a standard house design roughly corresponded to a standard village design. Above the airport in the Cuzco Valley, the remains of Qotakalli present a more ordered picture of Inka commoner village organization. Buildings within this settlement conform to an orthogonal layout. But, much like other Inka commoner villages, pathways and access points within Qotakalli are open and permeable (see Niles 1987: 37–40).

In attending to these differences in spatial organization, we see how a unitary Inka political landscape was assembled through the production of diverse environments. The Inka landscape of the Cuzco region was certainly constituted by a recognizable aesthetic of power, a claim to absolute authority that was expressed and supported by august monumental architecture and strategically positioned administrative centers. Yet this aesthetic, this appearance of regional coherence, relies upon a fragmented and fractured landscape—a series of sharp internal boundaries that would have influenced the ways that different people engaged with and perceived their environment.

The data thus provide a preliminary glimpse of a political regime’s strategy to shape social experience and perception, and in so doing, to create an ordered social and political landscape. The social and spatial boundaries recorded here are the remains of a state project to create a legible landscape (Scott 1998; see also Mitchell 1988; Smith 2003). Such a project seeks to monitor, divide, and differentiate space according to a governmental and administrative fantasy of rational order (Alonso 1994; Rose 1996). In considering such a state project, we must also examine how space is often designed to be “read” by users in specific ways. The example here suggests that Inka subjects inhabited an environment that bolstered and produced ideas of social distinction. Space appears to be ordered and “classed.” Put simply, to be an Inka subject was to know one’s place.

Conclusions: A Geography of Difference

In attending to spatial boundaries and barriers throughout a built environment, we can comprehend the social fault lines through which a political landscape, and political power itself, is constituted. Such a methodological perspective complements more conventional econometric and interpretative approaches by revealing how a semblance of cultural or social consistency—a “region”—coexists alongside, and is constituted by, a geography of discernable social and environmental differences. Archaeological GIS analyses would do well to further develop techniques for uncovering how social categories and distinctions are constituted in multiple, often contrasting environments. After all, the social distinctions and boundaries that underpin a political landscape do not simply emanate from monuments or settlement networks. Such boundaries are reproduced in the very places, practices, and perceptions through which people define, engage with, and live within their environment.

This paper provided a view of how archaeologists might use GIS to examine how distinct subject positions and social statuses are in part constituted through material and environmental differences in the perception and experience of spaces and places—differences that social actors must have managed and mediated through practice (sensu Harvey 1996). The analysis demonstrates how the investigation of interrelated multi-scalar spatial data sets can lead to productive interpretations of how various social actors may have perceived, experienced, and used spaces and places in different ways. Such an approach demands that we consider how political power is produced and maintained through space by examining how visions of social inequality are often supported by geographies of difference.

Notes

Some GIS researchers have improved upon this approach and its strict econometric logic. They have generated novel multi-criteria cost surface analyses that consider how cultural choices, such as predilections toward avoiding landscape features like mortuary monuments, influence people’s movement through and experience of the environment (Bell and Lock 2000; Howey 2007; Llobera 2000).

We conduct a regional, synchronic study of architectural and environmental variation in the Ollantaytmbo area at the apex of Inka power (ca. 1400–1532 ad). Currently, we lack the chronological precision to study diachronic processes that may have occurred during the Cuzco region Inka period. Yet excavations, regional surveys, and radiocarbon dates suggest that many Inka sites were continually occupied throughout Inka rule (e.g., Bauer 2004; Covey 2006; Dwyer 1971; Kendall 1985, 1996; Kosiba 2010; McEwan et al. 2002). In this light, our study considers an accreted Inka landscape—the settlement patterns, monumental enclosures, and grandiose elite estates that defined the Cuzco area on the eve of the Spanish invasion.

Although there are certainly local variations and styles (see Morris and Thompson 1985), Inka buildings are typically rectangular, stone, hip-roofed, stand-alone, one-room structures with a single door opening onto a patio space (see examples in Gasparini and Margolies 1980; Kendall 1976; Niles 1987). Residential buildings often exhibit only slight variations on this form. Elite residential structures are simply larger and stylistically embellished versions of archetypical commoner houses. The elite residential structures do not usually contain any additional internal spatial divisions, like interior rooms, hallways or receiving areas.

It is possible that some R1 buildings in MPT were demolished or eroded. However, the general regional and intra-site patterns observed throughout the study clearly indicate that R2 and R3 were constructed in and near such landsMPT.