Abstract

This article investigates whether acts of plagiarism are predictable. Through a deductive, quantitative method, this study examines 517 students and their motivation and intention to plagiarize. More specifically, this study uses an ethical theoretical framework called the Theory of Reasoned Action (TORA) and Planned Behavior (TPB) to proffer five hypotheses about cognitive, relational, and social processing relevant to ethical decision making. Data results indicate that although most respondents reported that plagiarism was wrong, students with strong intentions to plagiarize had a more positive attitude toward plagiarizing, believed that it was important that family and friends think plagiarizing is acceptable, and perceived that plagiarizing would be an easy task. However, participants in the current study with less intention to plagiarize hold negative views about plagiarism, do not believe that plagiarism is acceptable to family, friends or peers, and perceive that the act of plagiarizing would prove difficult. Based on these findings, this study considers implications important for faculty, librarians, and student support staff in preventing plagiarism through collaborations and outreach programming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Most, if not all, universities across the United States have policies or guidelines that deal with academic dishonesty and cheating. Current research establishes that there are few differences between cheating and plagiarism; however, plagiarism is a form of cheating that disregards academic values (Barnes 2014). Cheating is considered an intentional act that has a broader meaning and refers to violating rules for some benefit or gain (Gross 2011; Hosny and Shameem 2014). Plagiarism is conceptualized as both an intentional and unintentional act and thus is difficult for universities to assess, defeat or define as an unethical practice in the minds of students. This is partly because intentional and unintentional plagiarism includes a range of behaviors (i.e., paraphrasing or direct quoting without citation, reusing assignments from class to class, buying papers to submit as original work) and motivations (i.e., not enough time, laziness). More than 50 % of students admit to some form of cheating or having strong views about cheating (Hosny and Shameem 2014; Lambert and Hogan 2004). These views do not generally align with the viewpoints of academic institutions as a serious offense (Ashworth et al. 1997).

According to Walker (2010), there are no reliable data on how often plagiarism occurs and less reliable data on whether plagiarism is intentional or due to laziness. A number of studies support that there is a lack of reliable data on the frequency and occurrence of plagiarism. First, researchers report students’ acknowledgment of cheating and the reasons they cheat (Power 2009), but how often cheating happens is still unknown. Second, researchers in a variety of countries point out information retrieval software systems that detect text matching (Turnitin.com 2013; Stapleton 2012; Howard and Watson 2010; Pecorari 2013; Sutherland-Smith 2010) and its ability to deter plagiarism (Olutola 2016). Third, studies on contract cheating, another form of plagiarism in which someone is commissioned to do work on behalf of another, is often beyond electronic detection (Clarke and Lancaster 2007). Finally, honor codes, which are North American specific, have little to limited value in global contexts where the appropriation of language facilitates learning. Honor codes tend to place the responsibility of cheating on the student rather than the university structure, policy, and classroom instruction (McCabe and Trevino 2002; Roig and Caso 2010). Thus, obtaining an accurate measure of plagiarism, which has its own challenges and concerns, comes most accurately through trustworthy human reporting about dishonesty (Rakovski and Levy 2007).

One major assumption underlying academic misconduct is there is no foolproof method of abating it on college campuses, including the use of software systems that pick up the use of sources in written work (e.g., Turnitin.com), writing programs and centers that aid students in becoming better writers, informing students through instruction about what constitutes plagiarism, and obligating student’s to uphold the university’s honor code. However, making plagiarism transparent so that students can implement the appropriate ethical skills is critically important (Kiehl 2006; Sutherland-Smith 2014). Having knowledge of (direct understanding) rather than knowledge about (indirect understanding) plagiarism reduces opportunities for academic misconduct to occur intentionally. In addition, assessing the intent and motivation to plagiarize can signify one’s propensity to participate in academic misconduct.

Although research exists on what drives individuals to plagiarize (Bloch 2012), the literature is lacking empirical research that predicts students’ motivations to plagiarize. Understanding student attitudes toward plagiarism and their behavioral intentions to plagiarize generates a new lens with which to examine the plagiarism phenomena and raises questions about ethics and values. Although individuals don’t always act on intentions, intention to perform a behavior is a predictor of actual behavior (Mavrinac et al. 2010) and may provide opportunities for addressing plagiarism before it can be performed. Thus, the purpose of this study is to fill the gap by investigating the relationship between ethical attitudes toward plagiarism and behavioral intention from a psychological and ethical lens rather than a legal one. This study considers that acts of plagiarism with certain trait-distinguishing features (i.e., attitudes toward plagiarism and the intent to plagiarize) can be predicted through ethical binaries of planned behavior and reasoned action.

Literature Review

Plagiarism or Literary Remixing?

Much of the research on plagiarism focuses on attitudes and perceptions (see Risquez et al. 2013). However, research findings in the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the UK suggest that there is a perception gap related to how students and staff define and think about plagiarism (Pickard 2006; Simon et al. 2004) and what behavior constitutes plagiarism (Yeo 2007). This may seem like a common sense observation, but North American, South American, Asian, African, and European countries approach and understand plagiarism differently (Muhammad et al. 2012; Olutola 2016). Thus, to understand these issues further, we refer to four distinct perspectives: (1) awareness of plagiarism, (2) perceptions and attitudes about plagiarism, (3) steps to borrowing the work of others, and (4) the use of online resources.

Awareness, Motivation, and Intent

The first perspective focuses on the subjective understanding of plagiarism. This body of research has a long history and addresses how individuals contextualize plagiarism. Although how plagiarism is understood directly impacts how the work of others is borrowed and used, the intentions and motivations for plagiarizing is a more compelling and related focal point. Power (2009) and others (Pickard 2006; Yeo 2007) note that students are generally unaware of what constitutes plagiarism and believe that if they are summarizing and not copying word-for-word, the act of borrowing the work of others is not an act of plagiarizing (Lau et al. 2013).

Although many students often misunderstand the meaning of plagiarism, there is also variability and almost no agreement among staff and administrators on what constitutes plagiarism (Choo and Paull 2013; Flint et al. 2006). This lack of clarity not only demonstrates unshared meaning in distinguishing what Flint et al. call “acceptable paraphrasing and plagiarism” (p. 147), but an unshared framework or common ground presents a number of challenges for the academic community. These challenges include, but are not limited to the following: (1) lack of understanding of cheating and plagiarism and avoiding it, (2) differential treatment of students, and (3) institutional management strategies, procedures, processes and policies (Flint et al. 2006; Sutherland-Smith 2010). Another challenge is assessing plagiarism from multicultural perspectives.

With today’s literary environment, the boundary between what is mine and yours is fading. Therefore, to pursue a standard of accountability in higher education across North America and Europe, universities are creating academic cultures that deter acts of plagiarism through technological and instructional approaches, and considering cultural writing practices (Conway and Groshek 2008; Ehrich et al. 2016). Postle (2009) and others (Choo and Paull 2013) outlined steps for assessing plagiarism and systematic learning strategies. First, one should ascertain the type of plagiarism act used. The act might be a mistake rather than intentional. Second, consider cultural factors. International students, as well as national and first generation students, have a different understanding of what constitutes plagiarism (see also Leask 2006; Olutola 2016). Individuals may lack the appropriate experience to cite properly because plagiarism is culturally constructed (Conway and Groshek 2008), which begs the question whether plagiarism is an educational issue or an ethical issue. Third, if there is a zero tolerance policy in place, make a decision about who needs to be involved, if anyone. If the violation is unintentional, handling the issue with the student first is an effective decision, but university policy may require reporting the incident to department heads, the dean, or student affairs. Finally, meet and talk to the student directly about plagiarism. Expressing what you think of the student’s writing will allow the student an opportunity to explain what motivated him or her to take a particular action that led to plagiarism.

What motivates an individual to plagiarize is also associated with awareness or inadvertent behavior (Flint et al. 2006; Park 2003). The motivation to plagiarize relates to a number of influences including procrastination and personality (Siaputra 2013; Stone et al. 2010). Bennett (2005) suggests four factors that explain why individuals might plagiarize including academic assimilation, individual workload, personal ethics, and the availability of resources and opportunity. Park (2003) suggests there are clear messages about the seriousness of purposeful plagiarism, but mixed views on unintentional plagiarism. He further defines purposeful plagiarism as a premeditated act with full knowledge and intent to deceive the reader of the text. However, other motivations for plagiarism include unintentional, negligent, accidental and sloppy, careless mistakes that often go undetected (Collins et al. 2007; Howard 1995). Yet, intent is hard to detect and leads to speculation about associating plagiarism with one’s ethos. Flint et al. (2006) note that when plagiarism is linked with cheating, it is perceived to be an intentional act which provides a clear connection to ethical behavior. In their study, cheating was linked with exams/tests and plagiarism with coursework. Therefore, the form of assessment influences perceptions surrounding intentionality rather than accidental.

On the other hand, accidental plagiarism occurs when one is unaware of the appropriate protocols for referencing academic work. For international audiences, there is extensive literature on borrowing work that is viewed through a different lens and is linked to the educational process (i.e., unintentional plagiarism). Howard and Watson (2010) and Amsberry (2009) suggest that borrowing the work of others is a textual strategy that functions in two ways that requires an adjustment in perceptions of and response to plagiarism. First, borrowing the work of others is part of cross-cultural practices in which appropriated language is one of many acceptable factors. Second, international writers transition into discourse community to acquire the proper skills for educational writing. This relationship with the text, when regulated, expedites collaboration between two types of authors. The transformation of the original text by one of the authors makes the arrangement of someone else’s work is what Thompson (2009) calls intertextual (relational) in nature. In other words, there is a collaboration between the encoder, the composer of sentences, and the decoder, the restructurer of sentences.

However, Ha (2006) warns us against using common myths for international students and writing practices. He further suggests that showing reverence for an academic source does not translate to accepting plagiarism. Inappropriately using a source is considered unethical; especially in Vietnamese culture. Thus, plagiarism behavior, whether accidental or intentional necessitates an appropriate assessment and a different interpretation that assists and corrects the behavior rather than defining writing practice as cultural. Doing so further inhibits the learning process, while criminalizing and justifying the behavior (Sutherland-Smith 2011).

Western constructs of ownership of knowledge romanticize individuals as creators of text (Sutherland-Smith 2005). Thus, lack of knowledge related to plagiarism is inexcusable behavior. This lends itself to an ongoing debate as to whether claims of limited knowledge about what is acceptable academic referencing creates a defensive rhetoric of justification and potentially “hinders actions against the perpetrators of plagiarism” (Kock and Davison 2003, p. 513). However, in legal theory and literary theory, this may not be the case. The interpretation of what is acceptable source citation comes under theories of authorship attribution drawn from different perspectives on legal notions of owning words that consider other forms of academic referencing as appropriate (see Howard 1995; Lunsford and West 1996; M. Randall 1989, Sutherland-Smith 2008). Nonetheless, researchers have focused on techniques for reducing intentional and unintentional plagiarism to increase student understanding (Barry 2006; Landau et al. 2002) and the “shuttling between discourse communities” that explores trying to balance different forms of writing from different cultural perspectives (Canagarajah 2010).

Social Norms and Plagiarism

The second perspective on plagiarism suggests that the greatest predictor of student cheating or the propensity to engage in cheating is how similar students perceive their cheating behavior to be to that of their peers and friends (McCabe and Trevino 1996; McCabe et al. 2001b). Although cheating is different from plagiarizing, there is overlap. When a culture of cheating is present on college campuses, it increases the propensity to cheat (Engler et al. 2008). These conclusions are directly aligned with the social norms literature (Perkins 2003). Social norms research generally supports the idea that the decision to plagiarize operates on one’s beliefs about other people’s moral behavior and actions. Social norms research assumes that perception of peer behavior has a powerful influence over one’s decision-making regardless of perceptual accuracy. For instance, McCabe et al. (2001a) found that students in honor code environments report cheating more than those not in honor code environments. Engler et al. (2008) later found that students at a small university without an honor code made decisions to cheat. The results of students cheating support the idea that peer and friendship acceptance and the similarity is a determining factor in making decisions to act. Thus, the findings give insight into the role of perception in a student’s decision to engage in plagiarism.

Borrowing Other’s Work and Technology

The third perspective, based on extensive research, examines how already existing work is borrowed or used by students who plagiarize or have been charged with academic misconduct. Howard (1995, 2007, 2009) and Williams (2007) argue that online sources have complicated things by making information widely accessible, which in turn destabilizes individual authorship. Williams further notes that students have become a “culture of samplers” (p. 352) that create texts as an amalgam of other people’s work. However, borrowing practices are important to understanding because they lead to accusations of source misuse with varied consequences. Shi (2004) examined different types of textual borrowing based on interviews, case studies, and personal observations. The author notes that six strategies used included patchwork, summarizing, exact copying, paraphrasing, quotations and original explanations.

The fourth perspective refers to the collusion of plagiarism behavior with online resources. Because the Internet makes access to resources more readily available, it provides a means and a favorable circumstance for plagiarizing (McKenzie 1998). McCabe et al. (2001a, b) suggests that technology has impacted the ways in which people cheat in the form of paper mills (Whiteneck 2002), search engines (Laird 2000; Lathrop and Foss 2000; McCullough and Holmberg 2005), and internet articles and journals (Young 2001). Thus, technology is the new culprit and has been implicated in the increase in plagiarism behavior, as a number of scholars argue that plagiarism has more to do with the design of assessment than the arrival of internet technology (Carroll 2005; Howard 2007; Howard and Davies 2009).

Whether an intentional act on the part of the plagiarizer or if technology impacts one’s access and ability to plagiarize, plagiarism done with intent is considered a decision-making process that requires an individual to take a series of rationalized and consciously planned steps (McCuen 2008) rather than a learning strategy or form of rhetoric reflecting a cultural tradition (Sutherland-Smith 2005). Whether students have participated in plagiarism or not, there are two combined ethical theories that are relevant for understanding ethical decision making: The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. Both theories provide the backdrop for our understanding of plagiarizing as an ethical decision through volitional (choice) behavior that predicts based on certain cognitive and reasoning factors that exhibit one’s permissiveness toward or away from plagiarism behavior. These ethical theories serve as the theoretical foundation for this study.

Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior

The theory of reasoned action (TORA) and its extension, the theory of planned behavior (TPB), as described initially by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) and later by Ajzen (1991), suggests individual behavior can be predicted because behaviors can be intended and calculated. Grounded in organizational behavior and human decision-making processes (Ajzen 1991), the theory of reasoned action/planned behavior derived from attitudes research and decision-making processes within a variety of contexts. Therefore, the assumptions informing TORA/TPB are as follows: (1) an individual’s attitude toward the behavior in question, (2) subjective norms regarding the approval or disapproval of significant others, and (3) perceived behavioral control related to perceptions about the ability to perform the behavior.

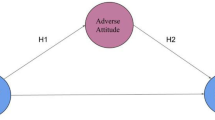

Recently scholars used the theory of reasoned action and planned behavior to explore technology (Yousafzai et al. 2010) and substance education (Sharma 2007). Of particular interest to this study are earlier investigations on ethical behavior (Chang 1998; D. Randall 1989) referencing business ethics and the illegal copying of software. D. Randall first tested the validity of the theory of reasoned action and planned behavior in the 1980s, followed eighteen years later by Chang’s study, which compared the theory of planned behavior with the theory of reasoned action. Although both studies were concerned with software piracy, Randall’s investigation resulted in Chang finding that TPB was a better predictor of unethical behavior than TORA (1998). According to Chang, perceived behavioral control, which comes from the theory of planned behavior, is better at predicting behavioral intention than attitude, which is associated with the theory of reasoned action. The variables attitude, subjective norms, and behavioral control combine to activate behavioral intention, which activates the behavior. In other words, the observable behavior that people perform is predictable. For TPB, intention predicts behavior, which is willful and purposeful action. Therefore, this study aims to answer the following hypotheses:

H1:

Attitudes toward plagiarism (ATT/PAP) will be significantly related to behavioral intention (BI). That is, favorable (unfavorable) perceptions of plagiarism will be associated with the intention to (not) engage in plagiarism.

H2:

Subjective norms about plagiarism (SN) will be significantly related to the behavioral intention (BI). That is, perceptions that important people agree (disagree) with the act of plagiarism would be associated with the intention to (not) engage in plagiarism.

H3:

Intentions to plagiarize (BI) will be predicted by perceived behavioral control (PBC). That is, one’s intention to (not) engage in plagiarism will be associated with perceptions that one has the competency to engage in plagiarism or that barriers may inhibit or support plagiarism.

H4:

There will be a significant difference in the ATT, BI, SN and PBC of students who have been sanctioned for plagiarism and those who have never plagiarized, but no difference between those sanctioned and those who have never been caught plagiarizing.

H5:

Personal outcome evaluation will be significantly related to attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intentions.

Methods

Participants

A total of N = 517 undergraduate students enrolled at a large, public university in the southwestern region of the United States participated in the present study. A number of participants had to be removed from consideration because they failed to complete at least 15 % of the survey. The final sample consisted of 487 individuals, which included 192 males and 295 females ranging in age from 18 to 49 (M = 20.95, SD = 4.41). The majority of the sample was lowerclassmen (freshmen, n = 186; sophomores, n = 102) and most began their academic careers as freshmen at the study location (n = 337) with 146 individuals stating that they were transfer students. Students varied in major (e.g., Accounting, Art, Biology, Business Administration, etc.). In terms of ethnicity, most of the participants self-identified as: White/Caucasian (n = 176), Latino/Hispanic/Mexican American (n = 172), and Asian (n = 91), with the remaining ethnicities each representing less than 6 % of the sample (i.e., 29 African Americans/Blacks, 9 Native Americans, 1 Alaskan, 19 Pacific Islanders, 25 Middle Easterners, and 18 Biracial/Multiethnic).

Measures

The Attitudes Toward Plagiarism scale (ATP) developed by Mavrinac et al. (2010) to assess the Theory of Planned Behavior as it relates to plagiarism was utilized to test all hypotheses (see Appendix for a copy of the instrument). All additional measurement instruments are also presented. Unless otherwise noted, all scale items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Attitudes

Positive attitudes (13 items) and negative attitudes (8 items) were assessed. Sample positive attitude items include: “Sometimes one cannot avoid using other people’s words without citing the source because there are only so many ways one can describe something” and “It is okay to use previous descriptions of concepts/ideas, especially if the concept/idea itself remains the same.” Sample negative attitude items include: “Students who plagiarize do not belong in college” and “In times of moral and ethical decline, it is important to discuss issues like plagiarism and self-plagiarism on college campuses.” The positive attitude scale was found to be reliable (α = .86). The negative attitude scale was found to be reliable (α = .85).

Subjective Norms

Subjective norms were measured with 6-items. Sample items include: “Sometimes I am tempted to plagiarize because everyone else is doing it (e.g., other students, etc.)” and “Most of the students with whom I am acquainted with plagiarize or have plagiarized at least once.” All items were subjected to principal component analysis with varimax rotation, resulting in a satisfactory Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficient (KMO = .80). One component was produced with an eigenvalue >1.0. The scale was reliable (α = .78).

Perceived Behavioral Control

Perceived behavioral control questions were assessed with 11-items. Samples items include: “For me, to plagiarize would be easy to accomplish,” and “If I encountered a crisis that placed demands on my time, it would make it easy for me to consider plagiarizing on an assignment.” All items were subjected to principal component analysis with varimax rotation, resulting in a satisfactory Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficient (KMO = .90). Two components were produced with eigenvalue >1.0. The resulting two-component solution accounted for 65.40 % of the common variance. Given that this scale was purported to be uni-dimensional, it was treated this way in the presented study and found to be reliable (α = .90).

Behavioral Intention

Five items measured behavioral intent. Sample items include: “I will probably plagiarize in the future,” and “If I had the opportunity without penalty, I would probably plagiarize at least once.” Principal component analysis with varimax rotation resulted in a satisfactory Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficient (KMO = .81). One component was produced with an eigenvalue >1.0, accounting for 61.88 % of the common variance. The scale was reliable (α = .83).

Personal Outcomes

In order to assess personal outcomes (i.e., the importance of goals for personal attainment), 6-items were utilized. Sample items include: “It is important for me to have better grades” and “It is important for me to gain an education.” Principal component analysis with varimax rotation, produced with an eigenvalue >1.0, accounting for 74.88 % of the common variance. The scale was reliable (α = .84).

Plagiarism Experience

An additional four (4) items were created to assess participants experience with plagiarism. Specifically, they were asked if they: had been previously sanctioned for plagiarism, ever intentionally plagiarized, ever unintentionally plagiarized, and were wrongly accused of plagiarism when they had not done so. These items were all assessed on a categorical measurement scale (1 = No, 2 = Yes).

Demographics

All participants answered a series of demographic items, which includes: age, sex, race/ethnicity, and class standing.

Results

The data was assessed for normality (Kline 2005). Results indicated that data from one measurement scale, personal outcomes, was outside the normal range for skewness (i.e., −1.00 to 1.00). As a result, log transformations were performed to normalize the data. Zero-order correlations between variables assessing the Theory of Planned Behavior is presented in Table 1.

Hypothesis 1

predicted that attitudes towards plagiarism are predictors of behavioral intention. Specifically, it was hypothesized that negative attitudes towards plagiarism are a negative predictor (H1a) and positive attitudes is a positive predictor (H1b) of intention to plagiarize. The results of a standard multiple regression analysis were significant, F (2, 418) =140.16, p < .001, R 2 = .40. Negative attitudes toward plagiarism (β = −.09, t = −2.41, p < .05) negatively predicted intention to plagiarize, and positive attitudes towards plagiarism (β = .61, t = 15.84, p < .001) positively predicted intention to plagiarize. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Hypothesis 2

predicted that subjective norms would positively predict behavioral intention to plagiarize. The results of a bivariate regression analysis were significant, F (1, 452) =256.74, p < .001, R 2 = .36. Subjective norms positively predicted behavioral intention to plagiarize (β = .60, t = 16.02, p < .001). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Hypothesis 3

predicted that behavioral intentions to plagiarize are positively predicted by perceived behavioral control. The results of a bivariate regression analysis were significant, F (1, 450) =329.25, p < .001, R 2 = .42. Perceived behavioral control positively predicted intentions to plagiarize (β = .65, t = 18.15, p < .001). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Hypothesis 4

indicated that those who sanction plagiarism would differ from those who do not sanction plagiarism in terms of (a) negative attitudes, (b) positive attitudes, (c) intentions to plagiarize, (d) subjective norms, and (e) perceived behavioral control. A series of independent samples t-test revealed that those who sanctioned plagiarism (M = 2.83, SD = .38) indicated higher levels of subjective norms than those who did not sanction plagiarism (M = 2.18, SD = .76), t (455) = 2.27, p < .05, η2 = .01 (see Table 2). There were only significant differences in subjective norms, thus, this hypothesis was not supported.

Hypothesis 5

predicted that positive attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intention positively predict, and negative attitudes negatively predict personal outcome evaluation. Results of a stepwise regression were significant, F (1, 405) =68.88, p < .001, R 2 = .15. However, only negative attitudes predicted personal outcome evaluation (β = −.38, t = −8.30, p < .001). Therefore, the hypothesis was only partially supported. Additional path analyses revealed significant regression coefficients for all paths except negative attitudes - > behavioral intention and perceived behavioral control - > personal outcome (see Fig. 1).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that both the TORA model and the theory of planned behavior were strong correlates of and predictors of intention to engage in plagiarism. Unlike the findings in previous research (Stone et al. 2007), positive attitudes (ATT) and subjective norms (SN) were predictive of behavioral intention (BI). In the present study, the data found that students’ attitudes toward plagiarism were aligned with their perceptions that important people in their lives (e.g., family, friends and/or peers) held the same view. Although this is not a new finding, the results suggest that ethical environments are supported by ethical interactions and that plagiarism can be improved by encouraging the support of peers, family, and friends. Furthermore, intentions to plagiarize were tied to their perceptions of whether important people were positive or negative toward plagiarism. Indeed, the literature supports that there is pressure to plagiarize, whether self-imposed or otherwise (McCuen 2008), and this pressure, as accounted for in our measure of perceived behavioral control (PBC), is an impetus for moving individuals through the decision-making process toward plagiarism (BI).

Furthermore, the current study found that whether students believed that plagiarism was something they could do because they had control and the ability to plagiarize (PBC) was a strong predictor of intention to plagiarize (BI). The idea that students will plagiarize if given the opportunity is not a surprising finding. At first, it appears the evidence on perceived behavioral control supports the basic threat of an academic sanction. However, as the literature of plagiarism detection software points out, it is an inexact science at best (Sutherland-Smith 2010; Carroll 2005). Therefore, if the software does not do as promised and sanctions are not easily enforced or even an option, students will probably realize this, and hence, perceive that they can plagiarize as they wish.

Moreover, students who are sanctioned versus no experience of being sanctioned when compared yielded no support, but an interesting finding was that those who had been sanctioned had higher levels of subjective norms. In other words, if people you are close to having also plagiarized and agreed, one might think that plagiarism is acceptable or may be more susceptible to pressure to plagiarize. This finding is supported by previous research. McCabe et al. (2001a) suggest that peer behavior is the most influential for cheating behavior. Additionally, Lim and See (2001) found that students were ethically ambivalent and accepting of dishonesty among their peers. The motivation to comply with important others is an appropriate conclusion for plagiarism and subjective norms.

Negative attitudes (moral decline) toward plagiarism was the only significant prediction of personal outcomes (important to have better grades). The more people who indicated that plagiarism was wrong or immoral the less likely they were to indicate that plagiarism is an option for getting better grades. Most often the thought was people who plagiarize do not belong in college. The literature on planned behavior would point out that this negative correlation would maximize behavioral changes. Ajzen (1985), Ajzen 1988) would predict that a dislike for plagiarism would proceed a behavioral change in a negative or positive direction. These changes would be attributed to one’s behavior toward plagiarism.

Therefore, while not suggesting universities get rid of plagiarism detection efforts, perhaps the focus needs to be on outreach and instruction appealing to student attitudes and subjective norms, along with an assessment of their effectiveness. The general reduction in peer pressure (subjective norms) and attitudes towards plagiarism may be a beneficial and positive consequence of plagiarism behavior.

Limitations and Future Directions

The first limitation was not being able to follow the initial research design to compare students currently or previously sanctioned to those students with no academic sanction for plagiarism. Because few students reported sanctions for plagiarism, the results could not provide evidence that previous behavior would influence future plagiarism one way or another. Therefore, future research might consider comparing sanctioned and unsanctioned groups, if feasible, perhaps through qualitative methods, as one would expect that the number of students formally sanctioned for plagiarism is relatively small.

The second limitation related to a time interval issue proposed by Werner (2004). In the time interval, the intention and the actual behavior could change over time. Since positive attitudes toward plagiarism and subjective norms were predictors of behavioral intention, with subjective norms being the greatest predictor, we further suggest that attitude and subjective norms are not rigid and static and could change over time signifying that plagiarism is less likely to occur. Relationships and people change over time, so friends and family who are important at one period could become more or less important at another point in time. Also, life changing events/experiences, spirituality, morality, and individual maturity set in as one matriculates through academic programs and through life that change and influence intention toward actual behavior. Indeed, Ercegovac and Richardson (2004), citing Kohlberg’s Stages of Development in Moral Reasoning, suggest that tiered instruction, from elementary school through college, should be designed to influence moral reasoning in relationship to plagiarism, and not simply rely on defining plagiarism and its ramifications, and teaching citation styles. Therefore, future research could follow a cohort of students to see if attitudes toward plagiarism change over time.

Finally, the variable, behavioral intention, presented a limited vision of why students plagiarize. The complexities of why and how students might plagiarize were limited. The alternatives offered to respondents for measuring behavioral intention were not exhausted. For example, plagiarizing is not just a question of being ‘acceptable’ or ‘easy’ or not. Sometimes, students who do not think plagiarism is acceptable, but have failed an assignment and are pushed for time, take plagiarizing as an option. These students do not fit into any of the categories and this is just one example.

Conclusion

As was demonstrated in this study, the theory of reasoned action/planned behavior is a useful model for predicting intentions to plagiarize as a function of one’s attitude toward plagiarism, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Applying this understanding of student attitudes and behavioral intentions to student outreach, information literacy instruction, and assessment presents opportunities for librarians and faculty to collaborate on finding or modifying methodologies to combat plagiarism (Lampert 2008).

The limited number of articles that have used this theory to research plagiarism is an indication that there are opportunities for future research. This paper was a preliminary beginning to such an approach linking plagiarism to a theory that would predict the misconduct before it happens. The theory of planned behavior and reasoned action makes an important contribution to the field. This contribution points us toward implementing programs and pedagogical practices within the classroom and as part of non-academic or academic support programs (i.e., writing centers, student affairs, orientation programs, first-year programs, etc.) that build on the theory to redirect behavior away from plagiarism and misconduct.

Focusing on what students perceive about plagiarism and their struggles through instructional means is far more useful in reducing plagiarism instances than knowing why students plagiarize. By executing collaborations between librarians and instructional staff, developing plagiarism tests and tutorials as course credit produces knowledge of plagiarism and provides insight into one’s intent to plagiarize. Thus, when plagiarism is performed after passing a plagiarism test, it is not an unconscious act and can be addressed with more training. These plagiarism tests help to foster an environment of integrity.

With respect to understanding student attitudes toward and about plagiarism, their intent to plagiarize and their subjective norms, a short assessment survey will aid academic resource staff in following a deductive logic approach to mitigate student misconduct. In other words, students who score high on plagiarism intent (if the instrument is answered honestly) could be directed to outreach training programs and online tutorials related to student leadership and peer group take a stand against plagiarism (SN) campaigns. This effort might influence student attitudes through positive peer pressure (ATT), much like the anti-substance abuse campaigns sponsored by government agencies. Anti-Plagiarism Campaigns dedicated to plagiarism testing, workshops and discussions demonstrate the seriousness the university takes in educating its students about ethics and its importance in a variety of contexts. Workshops, training or class activities could be part of course content or academic support programs. Activities related to “paraphrasing content” could prevent unintentional plagiarism, but very little for intentional plagiarism. These activities require students to reinterpret easy to difficult sentences and paragraphs in their own words. Activities could be held in various departments sponsored by student group associations or through in-class instruction with small groups to enabling full participation or as individual assignments through multimedia outlets that will allow the student to participate on their own time and in private.

Furthermore, while the pedagogy of anti-plagiarism instruction often focuses on tools for and/or proper citation formatting, in terms of moral instruction related to intellectual property theft, and potential sanctions, we do not know if this intervention is effective. There are no methods for preventing intentional plagiarism. One’s intent to plagiarize is an ethical issue and cannot be addressed through external strategies because it is an internal matter. One can only be exposed to acceptable behavior, but the ultimate decision to comply is up to the recipient of the knowledge. Therefore, future research might focus on assessing student intentions to plagiarize pre- and post- anti-plagiarism instruction and/or student outreach programming that measures changes in attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral control.

References

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman (Eds.), Action-control: from cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Heidelberg: Springer.

Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Chicago: Dorsey Press.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Amsberry, D. (2009). Deconstructing plagiarism: international students and textual borrowing practices. The Reference Librarian. doi:10.1080/02763870903362183.

Ashworth, P., Bannister, P., & Thorne, P. (1997). Guilty in whose eyes? University students’ perceptions of cheating and plagiarism in academic work and assessment. Studies in Higher Education, 22(2), 187–203.

Barnes, B. D. (2014). Plagiarism, morality, and metaphor. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Proquest Dissertation and Theses (Accession order number: 3668689).

Barry, E. S. (2006). Can paraphrasing practice help students define plagiarism? College Student Journal, 20, 377–384.

Bennett, R. (2005). Factors associated with student plagiarism in a post-1992 university. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(2), 137–162.

Bloch, J. (2012). Plagiarism, intellectual property and the teaching of L2 writing: new perspectives on language and education. Brooklyn, NY: Multilingual Matters.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2010). A rhetoric of shuttling between languages. In P. K. Matsuda, M-Z. Lu, & B. Horner (Eds.), Cross-language relations in composition (pp. 158–182). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Carroll, J. (2005). Handling student plagiarism: moving to mainstream. Brookes eJournal of Learning and Teaching, 1(2), 1–5.

Chang, M. K. (1998). Predicting unethical behavior: a comparison of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(16), 1825–1834.

Choo, T., & Paull, M. (2013). Reducing the prevalence of plagiarism: a model for staff, students, and universities. Issues in Educational Research, 23(2), 283–298.

Clarke, R., & Lancaster, T. (2007, July). Establishing a systematic six-stage process for detecting contract cheating. In 2nd International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Applications, 2007. ICPCA 2007. (pp. 342–347). IEEE. doi:10.1109/ICPCA.2007.4365466.

Collins, A., Judge, G., & Rickman, N. (2007). On the economics of plagiarism. European Journal of Law and Economics. doi:10.1007/s10657-007-9028-4.

Conway, M., & Groshek, J. (2008). Ethics gaps and gains: differences and similarities in mass communication student’s perceptions of plagiarism and fabrication. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator. doi:10.1177/107769580806300203.

Ehrich, J., Howard, S. J., Mu, C., & Bokosmaty, S. (2016). A comparison of Chinese and Australian university students’ attitudes towards plagiarism. Studies In Higher Education, doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.927850.

Engler, J. N., Landau, J. D., & Epstein, M. (2008). Keeping up with the Joneses: Students’ perceptions of academically dishonest behavior. Teaching of Psychology, doi:10.1080/00986280801978418.

Ercegovac, Z., & Richardson, J. V. (2004). Academic dishonesty, plagiarism included, in the digital age: a literature review. College & Research Libraries, 65(4), 301–318.

Flint, A., Clegg, S., & Macdonald, R. (2006). Exploring staff perceptions of student plagiarism. Journal of Further and Higher Education. doi:10.1080/03098770600617562.

Gross, E. (2011). Clashing values: contemporary views about cheating and plagiarism compared to traditional beliefs and practices. Education, 132(2), 435–440.

Ha, P. L. (2006). Plagiarism and overseas students: stereotypes again? ELT Journal. doi:10.1093/elt/cci085.

Hosny, M., & Shameem, F. (2014). Attitudes of students toward cheating and plagiarism:University case study. Journal of Applied Sciences, doi:10.3923/jas.2014.748.757.

Howard, R. M. (1995). Plagiarism, authorship, and the academic death penalty. College English, 57(7), 788–806.

Howard, R. M. (2007). Understanding “internet” plagiarism. Computers and Composition, 24(1), 3–15.

Howard, R. M., & Davies, L. (2009). Plagiarism in the internet age. Educational Leadership, 66(6), 64–67.

Howard, R. M., & Watson, M. (2010). The scholarship of plagiarism: where we’ve been, where we are, and what’s needed. Writing Program Administration, 33(3), 116–124.

Kiehl, E. M. (2006). Using an ethical decision-making model to determine consequences for student plagiarism. Journal of Nursing Education, 45(6), 199–203.

Kline, T. (2005). Psychological testing: a practical approach to design and evaluation. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc..

Kock, N., & Davison, R. (2003). Dealing with plagiarism in the information systems research community: a look at factors that drive plagiarism and ways to address them. MIS Quarterly, 27(4), 511–532.

Laird, E. (2000). We all pay for internet plagiarism. Education Digest, 67(3), 56–60.

Lambert, E., & Hogan, N. (2004). Academic dishonesty among criminal justice majors: a research note. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 29(1), 1–20.

Lampert, L. D. (2008). Combating student plagiarism: An academic librarian’s guide. Oxford: Chandos.

Landau, J. D., Druen, P. B., & Arcuri, J. A. (2002). Methods for helping students avoid plagiarism. Teaching of Psychology, 29, 112–115.

Lathrop, A., & Foss, K. (2000). Student cheating and plagiarism in the internet era: a wake-up call. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Lau, G. K. K., Yuen, A. H. K, & Park, J. (2013). Toward an analytical model of ethical decision making in plagiarism. Ethics & Behavior. doi:10.1080/10508422.2013.787360.

Leask, B. (2006). Plagiarism, cultural diversity, and metaphor: implications for academic staff development. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(2), 183–199.

Lim, V., & See, S. (2001). Attitudes toward, and intentions to report, academic cheating among students in Singapore. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 261–274.

Lunsford, A., & West, S. (1996). Intellectual property and composition studies. College Composition and Communication, 47(3), 383–411.

Mavrinac, M., Brumini, G., Bilic-Zule, L., & Petrovecki, M. (2010). Construction and validation of attitudes toward plagiarism questionnaire. Croatian Medical Journal, 51(3). doi:10.3325/cmj.2010.51.195.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1996). What we know about cheating in college. Change, 28, 28–33.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (2002). Honesty and honor codes. Academe, 88(1), 37–41.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001a). Dishonesty in academic environments: the influence of peer reporting requirements. The Journal of Higher Education, 72(1), 29–45.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001b). Cheating in academic institutions: a decade of research. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 219–232.

McCuen, R. L. (2008). The plagiarism decision process: the role of pressure and rationalization. Transactions on Education. doi:10.1109/TE.2007.904601.

McCullough, M., & Holmberg, M. (2005). Using the Google search engine to detect word-for-word plagiarism in Master’s theses: a preliminary study. College Student Journal, 39(3), 435–441.

McKenzie, J. (1998). The new plagiarism: seven antidotes to prevent highway robbery in an electronic age. Educational Technology Journal, 7(8), 1–11.

Muhammad, R., Muhammad, A. M., Nadeem, S., & Muhammad, A. (2012). Awareness about plagiarism amongst university students in Pakistan. Higher Education, doi:10.1007/s10734–011–9481-4.

Olutola, F. (2016). Towards a more enduring prevention of scholarly plagiarism among university students in Nigeria. African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies, 9(1), 83–97.

Park, C. (2003). In other (people’s) words: plagiarism by university students literature and lessons. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(5), 471–488.

Pecorari, D. (2013). Teaching to avoid plagiarism: how to promote good source use. London: Open University Press.

Perkins, H. W. (2003). The emergence and evolution of the social norms approach to substance abuse prevention. In H. W. Perkins (Ed.), The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: a handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians (pp. 3–17). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pickard, J. (2006). Staff and student attitudes to plagiarism at university college Northampton. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/02602930500262528.

Postle, K. (2009). Detecting and deterring plagiarism in social work students: implications for learning for practice. Social Work Education. doi:10.1080/02615470802245926.

Power, L. (2009). University students’ perceptions of plagiarism. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(6), 643–662.

Rakovski, C., & Levy, E. (2007). Academic dishonesty: perceptions of business students. College Student Journal, 41(2), 466–481.

Randall, D. (1989). Taking stock: can the theory of reasoned action explain unethical conduct? Journal of Business Ethics, 8(11), 873–882.

Randall, M. (2001). Pragmatic plagiarism: authorship, profit, and power. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Risquez, A., O’Dwyer, M., & Ledwith, A. (2013). “thou shalt not plagiarize”: from self-reported views to recognition and avoidance of plagiarism. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.596926.

Roig, M., & Caso, M. (2010). Lying and cheating: fraudulent excuse making, cheating, and plagiarism. The Journal of Psychology. doi:10.3200/JRLP.139.6.485-494.

Sharma, M. (2007). Theory of reasoned action & theory of planned behavior in alcohol and drug education. Journal of Alcohol & Drug Education, 51(1), 3–7.

Shi, L. (2004). Textual borrowing in second language writing. Written Communication, 21(2), 171–200.

Siaputra, I. B. (2013). The 4PA of plagiarism: a psycho-academic profile of plagiarists. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 9(2), 50–59.

Simon, C. A., Carr, J. R., McCullough, S. M., Morgan, S. J., Oleson, T., & Ressel, M. (2004). Gender, student perceptions, institutional commitments, and academic honesty: who reports in academic dishonesty cases? Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(1), 75–90.

Stapleton, P. (2012). Gauging the effectiveness of anti-plagiarism software: an empirical study of second language graduate writers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 11(2), 125–133.

Stone, T. H., Kisamore, J. L., & Jawahar, I. M. (2007, June). Predicting academic dishonesty: Theory of planned behavior and personality. Proceedings of the 2007 Management Education Division of the Administrative Sciences Association of Canada. Retrieved from http://ojs.acadiau.ca/index.php/ASAC/article/viewFile/1203/1038.

Stone, T. H., Jawahar, I. M., & Kisamore, J. L. (2010). Predicting academic misconduct, intentions and behaviors using the theory of planned behavior and personality. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. doi:10.1080/01973530903539895.

Sutherland-Smith, W. (2005). The tangled web: internet plagiarism and international students’ academic writing. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 15(1), 15–29.

Sutherland-Smith, W. (2008). Plagiarism, the internet, and student learning: improving academic integrity. New York: Routledge.

Sutherland-Smith, W. (2010). Retribution, deterrence and reform: the dilemmas of plagiarism management in universities. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. doi:10.1080/13600800903440519.

Sutherland-Smith, W. (2011). Crime and punishment: an analysis of university plagiarism policies. Semiotica. doi:10.1515/semi.2011.067.

Sutherland-Smith, W. (2014). Legality, quality assurance, and learning: competing discourses of plagiarism management in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2013.844666.

Thompson, C. H. (2009). Plagiarism, intertextuality and emergent authorship in university students’ academic writing. PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies. doi:10.5130/portal.v6i1.775.

Turnitin.com. (2013, May 23). Does Turnitin detect plagiarism? [Web log post]. Retrieved April 2, 2016, from http://turnitin.com/en_us/resources/blog/421-general/1643-does-turnitin-detect-plagiarism.

Walker, J. (2010). Measuring plagiarism: researching what students do, not what they say they do. Studies in Higher Education, 35(1), 41–59. doi:10.1080/03075070902912994.

Werner, P. (2004). Reasoned action and planned behavior. In S. J. Peterson & T. S. Bredow (Eds.), Middle range theories: application to nursing research (pp. 125–147). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Whiteneck, P. (2002, July 8). What to do with a thought thief. Community College Week, 14(24), 4–7.

Williams, B. (2007). Trust, betrayal and authorship: plagiarism and how we perceive students. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. doi:10.1598/JAAL.51.4.6.

Yeo, S. (2007). First-year university science and engineering students’ understanding of plagiarism. Higher Education Research and Development. doi:10.1080/07294360701310813.

Young, J. R. (2001, July 6). The cat-and-mouse game of plagiarism detection. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 47(43), A26–A28.

Yousafzai, S., Foxall, G. R., & Pallister, J. G. (2010). Explaining internet banking behavior: theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, or technology acceptance model? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00615x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Camara, S.K., Eng-Ziskin, S., Wimberley, L. et al. Predicting Students’ Intention to Plagiarize: an Ethical Theoretical Framework. J Acad Ethics 15, 43–58 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9269-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9269-3