Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate the influence of the dimensions of the theory of planned behavior, gender and course majors on unethical behavior intentions among Generation Y undergraduates. The sample of this study comprises 245 undergraduates from a private higher education institution (PHEI) in Malaysia. The instrument of this study is developed based on concepts developed from extant literature. Reliability and validity is accessed using Cronbach’s Alpha and Exploratory Factor Analysis respectively. Social desirability bias was monitored utilizing concepts adapted from Phillips and Clancy (American Journal of Sociology, 77(5), 921–940, 1972). Multiple Linear Regression and Independent sample T-tests were used for hypotheses testing. As a whole, results indicate that egoism, utilitarianism and magnitude of consequences exerted significant influence on unethical behavior intentions. Peer influence was not significant. In terms of gender, unethical intentions among males were influenced by egoism and peer influenced while females by utilitarianism and magnitude of consequences. Business majors did not consider magnitude of consequences significant in unethical behavior intentions. Ethical values form the fundamentals of ethical culture within organizations and a business environment which is increasingly based on self-regulation. Ethics is an essential part of the holistic personal development of future business leaders. As such, by understanding ethical attitudes and perceptions, we can draw implications for the further enhancements of teaching and learning of Business Ethics in academia as well as the development of ethical culture in the Malaysian context. Educators, parents and society also need to realise their role in the ethical development of these future Malaysian leaders. The framework of this study could be extended to actual behaviors, adult samples and also account for religiosity and age. This study utilizes the established dimensions and framework of the Theory of Planned Behavior in bridging the gap of research in unethical behavior within the context of a PHEI in Malaysia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background of the Study

The world was awed by many financial scandals in the last decade for instance the fall of Enron, Worldcom, Tyco International, Arthur Anderson, Satyam (India) and Parmalat (Australia). In hindsight, many of these financial scandals occurred behind a veil of integrity and legalistic conformity. It is evident in many of these cases that greed in the pursuit of wealth drove trusted business leaders led them to ignore red flags and employ deceptive practices to obfuscate the real financial performance (Dharan and Bufkins 2008). Malaysia is not excluded from the calamity that continues to plague the corporate world. Malaysians have also witnessed increasing financial scandals locally since the 1990s involving Perwaja Steel, TRI Berhad, Transmile Group Berhad, Megan Avenue and Port Klang Free Trade Zone (Mat Norwani et al. 2011). Despite efforts of establishing and enforcing the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance since 2007 (Securities Commission 2012), Malaysia’s Corruption Perception Index has shown a gradual and significant deterioration since the 2000 as shown in Table 1. Prior to that, Malaysian managers have also perceived deterioration of ethical standards within organizations compared to the previous decade (Zabid and Alsagoff 1993). This development has negative implications on flow of foreign direct investment which is much sought after for economic development and achievement of developed nation status as propagated by Vision 2020.

Ethical boundaries are constantly being challenged in the contemporary business environment more than ever. Financial scandals have indicated that regulations may not be sufficient and also raised deep questions on the frailties human moral values (Kevin 2010). It is becoming increasingly evident that corporate governance needs to be guided by individual ethics and moral compasses. Hence, the studies of ethics continue to be the forefront of various disciplines. This includes marketing (Nantel and Weeks 1996), leadership and especially accounting (Vanasco 1998; Elias and Faraj 2010). Hence, it is crucial to identify the factors that are influences an individual’s decision when faced with ethically questionable situations. When faced with ethical problem, moral reasoning occurs progressively through four steps, namely ethical issue recognition, ethical judgment, ethical intention and subsequently ethical behavior (Jones 1991; Rest 1986). These steps vary between individuals depending on moral philosophies, personal values, and contextual factors (Barnett et al. 1994a). In line with this, Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) suggests that individual intentions are guided by attitude towards the behavior, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control. Previous research outside Malaysia has shown that TPB have been used to analyze intentions and behaviors ranging from ethically questionable consumption decisions, ethical decision making in the public accounting profession to intention to enrol in education programs (Chang 1998; Li et al. 2009; Buchan 2005; Fukukawa 2002). Only attitude towards behaviour and perceived behavioural control were found to exert significant influence on the intention to take up business ethics elective courses (Randall 1994).

In Malaysia, previous research have used TPB in analyzing issues such as pirated software purchases, recycling intentions, entrepreneurial intentions and mobile commerce adoption (Alam et al. 2011; Mahmud and Osman 2010; Mokhtar et al. 2010; Noordin and Sadi 2010). However, there is a lacuna in research within the Malaysia studying unethical behavior intentions by employing constructs within a specific and systematic theoretical model such as the TPB within a PHEI. This study adapted and extends the Hong Kong study of Chang (1998) in studying unethical intentions among undergraduate students in a private higher learning institution (PHEI) in Malaysia by providing insights to the following research questions:

-

RQ1: What influence do the constructs of TPB namely attitude towards behavior (Egoism and Utilitarianism), subjective norms (Peer influence) and perceived behavioral control (Magnitude of consequences) have on unethical intentions?

-

RQ2: Are TPB and unethical intentions influenced by gender and course majors?

Business ethics curriculum is commonly based on textbooks which are predominantly from the United States of America (USA) which generally hold the narrow view that business ethics begins “where the law ends”. However, with increasing globalization, there are international issues that transcend national boundaries and influence creating ethical grey areas for instance approach towards global warming. In such areas, there is a call for responsible business self- regulation. Increasingly, the influence of multinational companies (such as Wal Mart, General Electric) has gained a substantial credence over governments and types of legislation that are enacted. As such, it is becoming evident that ethics should be viewed as “where the law starts” and it would be futile to create a dichotomy between business and ethics in academic curriculum (Crane and Matten 2004). Unfortunately, the current business curriculum mind-set still promotes industriousness, affluence and consumerism as the mantra which inadvertently breeds irresponsible values. This is accentuated with the fact that business schools themselves are profit oriented (Owens 1998). To overcome this, there is an increasing need for these institutions to reflect and continuously question the ethical assumptions within our business courses to make them more relevant and sustainable. To make matters worse, students often perceived business ethics courses as a waste of time (Randall 1994). The domains of business ethics span to include topics on regional culture, individual and corporate culture, international regulations as well as institutional influence on civil society (Crane and Matten 2004). Students as future leaders will play a critical role in shaping the business ethics environment of the nation. As such by understanding ethical attitudes and perceptions, we can draw implications to promote greater relevance and effectiveness in the teaching and learning of Business Ethics in academia as well as the development of ethical culture in the Malaysian context.

Methodologically this study develops valid scales for the constructs of the study based on extant literature and attempts to control for social desirability bias (SDB) commonly associated with ethical surveys via development of a scale employing an adapted over-claiming scale using the concepts propagated by Phillips and Clancy (1972).

Literature Review

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) is built upon the foundations of the theory of reasoned action (TRA) and is widely used in the field of social psychology. Both the theories attempt to explain how attitudes, subjective norms and intentions lead to actual behaviors. Attitudes reflect an individual’s salient beliefs and moral norms. Subjective norms are normative beliefs that arise as a result of influence of significant referent groups on the individual (Ajzen 1991).

The TRA is restricted to the analysis of behaviors that are under volitional control of the individual which are behaviorismo that are generic, straightforward and easily mustered (Conner and Armitage 1998; Armitage and Conner 2001). However, when actions/behaviors require special expertise, resources or when opportunities are limited, TRA fails in its predictive capability. For this reason, TPB introduced the construct perceived behavioral control (PBC) to strengthen the explanatory power of the model (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Chang 1998). PBC reflects how an individual perceives the degree of ease or difficulty in the performance of a task (Ajzen 1991). It is closely related to the Bandura (1982) concept of self-efficacy which reflects the combination of the need for achievement, confidence and judgments of one’s capabilities to execute a task when faced with uncertainty on the magnitude of consequences.

In this study, the TPB the dimensions of attitude towards behavior will be investigated via egoism and utilitarianism. Subjective norms and PBC constructs will be investigated via the peer influence and magnitude of consequences dimensions respectively. Further elaboration on these constructs is provided under their respective headings below.

Unethical Behaviors Intentions

Ethics is a set of principles of what society or a group considers “right or wrong” (Ryan and Bisson 2011). Morals, on the other hand involve personal behavior based on ethics. Ethical decision making involves a process of issue identification, exercising moral judgment and formation of moral intentions within a dynamic and complex environment (Jones 1991; Treviño and Brown 2004). As such, moral judgments need to be based on ethical principles. Kohlberg (1969) cites three levels of cognitive moral development ranging from pre-conventional, conventional to principled. At pre-conventional level, individuals would generally adopt a self-interest view of ethics. Individuals at conventional level would adhere to ethics merely to satisfy the legal requirements and minimum level of social consensus. At the principled level, individuals seek to uphold social contracts over and above legal requirements as seek to adhere to universal ethical principles. However, in reality very few people arrive at Kohlberg’s “principled” level of cognitive moral development leading to potential unethical behavior and practices (Treviño and Brown 2004).

Ethics can also be viewed from a deontological or teleological approach (Macdonald and Beck-Dudley 1994). Deontological approach perceives ethics as a call of duty that needs to be performed regardless of the consequences. On the other hand, teleological approach considers the rightness or wrongness of the action bearing in mind the consequences. Within these two perceived extremes, there are grey areas in moral conduct. An act can be good but done for bad ends, for instance continuous provision for the poor but not helping them to stand on their own feet or done without dignity. Conversely an act can be bad but done for good ends, for example “Robin Hood” acts or Machiavellism. As such, individuals have room to rationalize, justify and/or trivialized unethical behavior intentions as they are tempted by greed and self-interest. This study investigates unethical behaviors such as lying, giving false information, telling white lies, over-representing one-self and under-reporting taxes.

Attitude Towards Behavior

Attitudes incorporate the values and belief system held by the individual (Ajzen 1991). The TPB operationalizes these beliefs as a reflection of the expectations and desirability of outcomes the individual perceives (Randall 1994; Buchan 2005). Various dimensions of personality traits, values and emotional intelligence have been used to capture the essence of attitudes towards behavior (Sommer 2005). However, in many other previous studies of ethical behavior, the attitude towards behavior is often treated as uni-dimensional (Randall 1994; Chang 1998). However, in a study of ethically questionable consumption behaviors, Fukukawa (2002) suggests that attitudes towards behavior be measured in terms of risk taking, expediency and consequence towards actor, other consumers and suppliers. In this study we capture the attitudes of risk taking and expediency in terms of egoism and consequence to others in terms of utilitarianism.

Egoism

Egoism is the attitude that upholds self-interest as the source of rational action and moral conduct (Kay 1997; Shaw and Barry 2010; Woiceshyn 2011). Individuals who score high on the egoism scale finds motivation from within to achieve an ultimate goal. These individuals see their action as the ultimate determinant of their future condition. Hence, they are willing take on high stakes in order to achieve a desired outcome. Although the act of exhausting all avenues is regarded as a positive trait, the act of intentionally harming others for personal gain is morally and ethically challenged. In this respect, ethics is opined by the egoist as not only required for survival but passport to a prosperous and happy life (Woiceshyn 2011).

Egoism can manifest in a range of enlightened egoism and Machiavellism attitudes. Enlightened egoism stipulates that the existence of others is merely a means to their ends. Thus, an egoist may appear to care for the interest of others if the action ultimately promotes their own selfish interests (Shaw and Barry 2010). While a good network support and human relation are considered to be important in the business world, an egoist would seize the opportunities to use others as an instrument to achieve their desired goal (Debeljak and Krkac 2008). On the other hand, Machiavellism is a political doctrine which denies the relevance of morality. Holding on to craft and deceit is justified in pursing and maintaining power. Such an individual would pursue his goal at the expense of others without a second thought (Kirkpatrick 2002). Ahmad et al. (2005) found that the decision making process is affected by the nature of egoism an individual adopts. Individuals would be inclined towards lower level of ethical reasoning when making decisions in situation concerning self-interest. Personal gain outweighs unethical, immoral or inconsiderate behaviors for an egoist. An egoist has the tendency to ignore the outcome of his decision on others in pursuit of his own greatest good, hence leading to conflict.

From another school of thought, the consequentialist theorist believe that in event where the good outcome outweigh the bad outcome, such decision or action is considered to be proper (Fieser 2009). Shaver (2010) further supports this theory by stating that an egoist is willing to pay a huge sacrifice in order to maximise his own interest. Though the outcome of a decision is uncertain, an egoist is willing to choose a decision which is perceived to be in his favour than the opposite. With this we hypothesise that:

-

H1: There is a positive relationship between egoism and unethical intentions.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is a concept that justifies an action as ethical if it brings the greatest food for the greatest number of people (Modarres and Rafiee 2011). This theory is known as the analysis of cover over its benefits (Saat et al. 2004). As such, decisions whether good or bad, is judged based on what individual believes to be the best course of action (Pearsall and Ellis 2011).

Utilitarianism manifest act and rule tranches (Rainbow 2002; Bushe and Gilbertson 2007; Smith 2010). Act utilitarianism involves performing an act or making a decision that ensures the benefit of the majority even though such action may violate the law. Nonetheless, the action is justified as it is perceived to be made in the best interest of majority. Rule utilitarianism, as the term defines it, is contrary to act utilitarianism as it takes into account the spirit rather than letter of the law and considers principles of justice and fairness. The act utilitarian has a higher possibility of behaving in an unethical way. It is a belief that decision should be based on its utility or usefulness. When weighing their options, the act utilitarian would regard social norms or law as unimportant and incline towards the most beneficial option (Pearsall and Ellis 2011). Most consider such thought or decision as ethical because no parties would be hurt, thus justifying their decision as to be the best option. Such decision is even more prevalent in situations where high psychological safety is perceived by individuals. Hence, individuals would be motivated by practicality to make decisions which are unethical. Pearsall and Ellis (2011) also found that individual who score high on the utilitarianism scale and perceived high psychological safety have a comparatively higher chance of cheating. However, utilitarian individuals would reconsider their action if the perceived environment is considered to be unsafe to behave in an unethical manner. This conclusion is parallel to that which was conducted by The Centre for Academic Integrity. It was reported that almost 75 % of the students admitted to be involved in engaging in some form of cheating (Cox 2009). This is because the University environment is considered to be high in terms of psychological safety and chances of being caught are low. Besides, over 70 % of the respondents surveyed across 60 campuses across the United States admitted to cheat on at least one written assignment (Smith et al. 2009). Internet plagiarists are also more inclined towards behavior justifications based on utilitarianism (Granitz and Loewry 2007).

Cultural difference may also motivate an individual’s intention (Carol 1999). Most studies conducted in Western countries among business students where results show a positive relationship between high utilitarianism and unethical conduct. Hence, this study seeks to test whether such a conclusion stands in an Asian culture where perceived psychological safety and utility may differ.

-

H2: There is a positive relationship between utilitarianism and unethical intentions.

Subjective Norms

Subjective norms are concerned with normative beliefs and motivation to comply with the particular behavior being investigated (Randall 1994). It involves an individual’s perception about what significant others would think about his/her decision to engage in a course of action (Randall 1994; Armitage and Conner 2001; Buchan 2005). In this study we investigate subjective norms using peer influence.

Peer Influence

There are three distinct dimensions to peer influence, namely exogenous effect, endogenous effect and correlated effect (Manski 1993). Exogenous peer effect can be understood as the preceding peer influence that has impacted an individual and how it forms a person’s perception towards unethical behavior in the present; for example the influence of high school peers and how student view cheating in a college setting. On the contrary, endogenous effect believes that an action or decision made regarding ethically challenged subject is influence by an individual’s current peers. Hence, it can be concluded that peer influence will, to a certain extent, influence an individual’s perception, intention and behavior towards moral conducts. Exogenous effect and endogenous effect focuses on an individual’s surroundings and assumes that such surrounding might be beyond the control of the individual at times. However, the dimension of correlated peer influence is defined as an intentional act of joining a selected group because of shared characteristics or perception despite whether such views are morally right or wrong (Carrell et al. 2007). This dimension differs from the first two as the individual is aware of the surroundings and deliberately seeks for support for an action taken.

Crutchfield (1955) concluded that conforming to majority in a social setting was a norm for most individual. The term peer influence was later redefined as the change in a decision or action by an individual as a result of the influence of a group decision (Gino et al. 2009). Peer pressure influences an individual’s view on unethical behavior ether as a standard norm of unacceptable or on the contrary being acceptable unethical decision that is observed by a specific group (Sutherland 1983; Jones and Kavanagh 1996; McCabe et al. 2001). It was also concluded in a studies that peer influence had a significant impact and influence on one’s behavior (Carrell et al. 2007).

-

H3: There is a positive relationship between peer influence and intention to be unethical.

Perceived Behavioral Control

When there are uncertainties surrounding a behavior that individuals do not have complete grasps over, there will be differing degrees of rational and moral judgment being exercised. Perceived behavioral control also reflects an individual’s belief on the level of difficulty in performance of a task given the limited opportunities and resources accorded (Randall 1994). The employment of TPB in examining morally sensitive intentions often invokes assessments of magnitude of consequences which are usually associated with the negative effects of being discovered. Examples of such studies are in the prediction of academic misconduct among students, environmental ethical decision making, counterfeit purchase intentions and music piracy on the web among individuals (Flannery and May 2000; d’Astous et al. 2005; Eisend and Schubert-Güler 2006; Stone et al. 2009).

Magnitude of Consequences

Magnitude of consequences as a construct was first defined by Jones (1991) as a dimension in a model of moral intensity involving the impact of a decision on another individual, whether the victim or the beneficiary (Jones 1991; Weber 1996; Bowes-Sperry and Powell 1999; Butterfield et al. 2000; Pauli and May 2002; Sweeney and Costello 2009; Kish-Gephart et al. 2010). Lincoln and Holmes (2010) refined magnitude of consequences as the degree or seriousness of the harm instead of looking at the total harm. Jones (1991) suggested that there is an inverse relationship between unethical decision and magnitude of consequences. Other research has also concurred in findings that a greater level of ethical and moral reasoning in decision making would be evoked when the consequences of an action is greater; for example, the issue of life and death (Weber 1996; May and Pauli 2002; Trevino et al. 2006). In terms of the TPB, magnitude of consequences is often contained within the perceived behavioral control dimension but the influence on intentions and behaviors are mixed (Chang 1998; Buchan 2005; Li et al. 2009).

Rest (1986) describes three stages of ethical decision making comprising moral issue identification, judgment and intention. Studies have investigated magnitude of consequences within the Rest’s (1986) model and often concluded that it is a significant factor influencing an individual’s conscience in ethical decision making (Harrington 1997; Bowes-Sperry and Powell 1999; Butterfield et al. 2000; Frey 2000; Dukerich et al. 2000; Flannery and May 2000; Pauli and May 2002). Further studies on the moral intensity framework concluded that magnitude on consequences is a significant influencing factor in a person’s ethical consideration (Morris and McDonald 1995; Weber 1996; Harrington 1997; Singer et al. 1998; Barnett 2001; Lincoln and Holmes 2010). As the magnitude of consequences of a decision, action or issue increases, the individual’s ethical intention increases, thus evoking higher level of ethical decision (Harrington 1997; Flannery and May 2000; Pauli and May 2002).

-

H4: There is a negative relationship between magnitude of consequences and unethical intentions.

Gender

The role of gender in ethical perception is extensively studied yielding mixed findings. In most studies, women were generally found to have more ethical intentions compared to man (Franke et al. 1997; Singhapakdi et al. 1999). This was noted in several settings such as consumer behavior (Bateman and Valentine 2010), marketing (Singhapakdi et al. 2001), and academia. There is a higher concern for ethical conduct among female students compared to their male counterparts in a college setting (Barnett et al. 1994b). Female students were generally found to be more ethical compared to males. Males were found more willing to actively and passively benefit from illegal actions compare to female students (Thoma 1986; Beltramini et al. 1984; Chai et al. 2009). Nonetheless, the difference was found to be more significant in younger age groups compared to older adults with similar working experience and exposure.

However, some studies found no difference in ethical believes between the genders (Rest 1986; Tsalikis and Ortiz-Buonafina 1990; Sikula and Costa 1994; Randall 1994). Male and female had the same ethical values and ranking in their consideration and conduct especially in situation where it is clear that the act is regarded to be illegal. The differentiating factor between male and female in moral behavioral intentions resulted from the differing moral reasoning. As male and female may view and perceive situation differently, the motivating and guiding factor in decision making differed. Gill (2010) noted that in India males were found to consider less diverse in decision making compared to females who readily invoke different ethical dimension for differing scenarios. Nonetheless, Bateman and Valentine (2010) noted that females still showed higher intention to behave ethically than males. Based on the observation above, the following hypothesis was formed:

-

H5A: Female student intend to behave more ethically compared to male students.

-

H5B: Gender is a moderator for the TPB framework.

Major of Study

Previous research have found that there is a positive relationship between cheating in an academic setting and in the workplace (Sedmak and Nastav 2010). Hence, students who have the tendency to cheat on an academic exam would in the same way regard cheating or morally questionable behavior as acceptable in the workplace. This is indeed a crucial area of research as these students would enter the work force eventually and set the moral platform on which businesses would function.

As the pressure to perform academically is increasing, students are often under highly stressed environment to meet the expectations of parents and future employers; hence leading student to engage academic dishonesty of some form (McCabe et al. 2001). While cheating among students is a common issue, Sedmak and Nastav (2010) noted that business major students have a higher tendency to cheat and act in a less ethical way compared to non-business major students (Sautter et al. 2008; Cox 2009). In line with these findings, Klein et al. (2006) found that there is a high positive correlation between academic cheating in university and cheating at work. Hence, it is important to identify groups of student who may have higher tendency of cheating in order to ensure that they are sufficiently equip with ethical training and courses in order to reduce the probability of academic cheating, and more importantly cheating at work. However, there are findings that show that the difference is not significant between business major students and non-business majors (McLean and Jones 1992; Barnett et al. 1994b; Ford and Richardson 1994; Lane 1995; Cheong 1999; Molnar et al. 2008). Another study conducted by Ethical Research Centre, found that at least one third of the workers were reported to act unethically at the workplace; with 56 % of them being business graduates compared to 47 % of non–business graduate students (Smith et al. 2009). Although it may be considered insignificant, Cox (2009) found that students did not consider cheating as an ethical issue because of the competitive and intense environment has indirectly promoted the need for cheating. Hence, students will most likely adopt this view when they enter the workforce and compromise certain ethical standards in order to meet the requirements of the performance measurement tool used by the organization. Despite the insignificance difference, business students still showed a higher probability of cheating. Based on the studies above, the following hypothesis is presented:

-

H6A: Business major student has a higher tendency to intend to behave unethically.

-

H6B: The major of study is a moderator for the TPB framework.

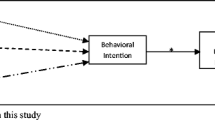

Figure 1 below depicts the conceptual framework in line with the TPB as well as the six hypotheses of this study.

Research Design and Methodology

A purposive sampling method was used as the objective of the study was to achieve theoretical verification of the conceptual framework rather than generalization to the population. The sample of this study comprises 245 undergraduate students from a private higher education institution in Petaling Jaya, Malaysia. Previous studies have often employed student samples in studies of ethical behaviors (Chang 1998; Chan and Leung 2006; Stone et al. 2009; Bateman and Valentine 2010).

Scale Development

The instrument of this study was developed based on the review of extant literature comprise general statements describing the constructs of the study. Wherever possible, general statements are used to retain the salience of the issues as well as encourage responses. General statements shortens the reading time compared to using vignettes, promotes greater spontaneity in responses and are in the format that the students in the sample are used to. Moreover, contextualizing items may not give equal weight to all issues and pose a limitation by inviting bias (Devinney 2010). Table 2 lists the sources in which the concepts and subsequently items of the scale of the constructs of the study were developed.

Validity and Reliability Testing

The inter-construct validity is verified via Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). The Principle Component Analysis is used in conjunction with the Varimax rotation method. In line with a sample size of between 200 and 250, the items were extracted based on a factor loading of 0.40 (Hair et al. 2010). Valid factors are indicated by an Eigenvalue of 1 and above. Due to the exploratory nature of this research, reliability is assessed based on a Cronbach’s Alpha of between 0.6 and 0.7 (Peterson 1994; Hair et al. 2010).

Hypotheses Testing

Hypotheses testing are conducted by employing the Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) function within the IBM PASW Statistics 19. As indicated by Fig. 1 above the independent constructs of this study are egoism (EGO), utilitarianism (UTIL), peer influence (PEER) and magnitude of consequences (MAGNITUDE). As stipulated in the TPB and conceptual framework above, unethical behavior (UNETHICAL_BHV) has been defined as the dependent construct. Significance is deemed to be achieved for hypotheses testing if the p-value is between 0.05 and 0.10 which is common for social sciences.

Independent sample T-tests are conducted to tests the difference between means of UNETHICAL_BHV between the gender and major groups.

Social Desirability Bias (SDB)

SDB occurs when respondents exert a tendency to portray themselves in a self-enhancing manner in self-report surveys (Paulhus et al. 2003). SDB usually causes responses that depart from reality when respondents rate themselves more positively or exaggerate their answers to create a more favourable impression of themselves. This is prevalent in surveys that require sensitive personal information in the fields of social science and psychology concerning areas such as consumer behaviors, personality traits and unethical behaviors.

SDB scales have been developed to access the extent of inflation or over-claiming of self-descriptions such as the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Bias (MCSDB) Scale (Crowne and Marlowe 1960) and Phillips and Clancy (1972) Over-claiming Scale. The MCSDB is originally a 33 item discrete scale which is designed to differentiate honest respondents from socially motivated ones based on expected exaggerated positivity. For example, “You always practice what you preach (True)” or “You sometimes try to get even rather than forgive and forget. (False)”. The discrete True/False in parentheses indicated have to be pre-determined as the expected socially desirable responses. The MCSDB Scale has been critiqued and seldom used in business research its lack of parsimony, lack of specificity to context of research (for example “Before voting I thoroughly investigate the qualifications of all the candidates.”) and the difficulty in establishing the valid from desirable pre-determined responses (Paulhus et al. 2003; Thompson and Phua 2005). Over-claiming techniques provide and alternate method in SDB testing. Over-claiming scales propagated by Phillips and Clancy (1972) intend to access the responses based on the extent of exaggeration of knowledge. Any claim of familiarity for example with non-existent movies, brands or consumer related items represents a possibility of self-distortion of responses in the actual survey. The advantage of over-claiming scales is that they are flexible and easy to design to account for cultural acceptability of respondents.

In order to monitor the extent of social desirability bias (SDB), a 5-item scale was developed based on the concept propagated by Phillips and Clancy (1972). In essence, respondents were required to indicate their familiarity to certain “non-existent” movies on a 5-point scale (1 = Not Sure at All to 5 = Very Sure). A response of greater than the mean of 3 would indicate above average over-claiming. Participation in the survey was purely voluntary with assurances of anonymity provided beforehand.

Study Findings

This section begins by describing the characteristics of the respondents of the study sample. Subsequently, it will provide the results of the measurement assessment, hypotheses testing as well as assessment on SDB.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 indicates that the respondents of the study comprise a majority of females (60.82 %), Chinese (78.37 %) and of the Buddhist faith.

Results of Validity and Reliability Testing

Based on the Pattern Matrix tabulated in Table 4 below, the Kaiser-Meyer Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy is 0.83 (above 0.70) and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity yields a Chi-Squared of 2023.59 (df = 378; p < 0.05). This indicates that the sample is suitable for the conduct of EFA. The results show that the independent (EGO, UTIL, PEER and MAGNITUDE) and dependent (UNETHICAL_BHV) constructs are valid as they all have Eigenvalues of above 1. The cumulative explained variance is 50.2 %. The Cronbach’s Alpha for UNETHICAL_BHV, PEER and EGO are above 0.70 whereas for MANITUDE and UTIL are between 0.60 and 0.70. As such, the constructs have satisfied the required thresholds of reliability for an exploratory research (Peterson 1994; Hair et al. 2010).

Results on Hypotheses Testing of H1 to H4–Application of TPB on the Overall Sample

Table 5 below indicates that the MLR has a F-Statistic of 8.728 which is significant at the 0.05 critical value. The table of coefficients shows that EGO and UTIL have a significant positive influence on unethical behavior. The t-statistic for EGO and UTIL are 2.81 and 3.84 respectively and are significant at p < 0.05. This indicates that hypotheses H 1 and H 2 are supported. However, PEER is not significant at p < 0.05. As such, hypothesis H 3 is not supported. It is however interesting to note that PEER had a negative relationship with perception of unethical behavior. On the other hand, MAGNITUDE is significant at p < 0.10. As such, H 4 is supported.

The relationship between the constructs of the study can be described as follows:

The Adjusted R-Squared is 0.115 indicating a medium to large effect size (Cohen 1992). The Beta coefficient indicates that Utilitarianism has the highest explanatory power on the perception on unethical behavior followed by Egoism and Magnitude of consequences.

Results of Hypotheses Testing on H5–Influence of Gender on Unethical Behavior

Table 6 tabulates the results of the Independent Sample T-Test for gender differences in perceptions of unethical behavior. This indicates that H 5A is supported at the critical value of p < 0.10 but not at 0.05. The mean for females was 28.47 and males 29.50 indicating that males have greater tendency towards unethical behaviors.

Results of Hypotheses Testing on H5A–Moderating Influence of Gender on the TPB Framework

The MLR in Table 7 indicates that the independent constructs of the study influence the perception of unethical behavior in different ways. In the case of males, PEER has exerts a significant negative influence on UNETHICAL_BHV at p < 0.10 and EGO exerts a positive influence on UNETHICAL_BHV at p < 0.05. On the other hand for females, UTIL exerts a positive influence and MAGNITUDE exerts a negative influence on UNETHICAL_BHV both at p < 0.05. This lends support to H5B that gender exerts a moderating influence in the application of the TPB.

Results of Hypotheses Testing on H6–Influence of Gender on Unethical Behavior

In terms of course majors, Table 8 shows there are significant differences in the means of perception of unethical behavior between respondents pursuing the business and non-business at the critical value of p < 0.10. Thus H6A is supported at p < 0.10 but not at p < 0.05. The mean for Business Majors is 29.59 whereas for non-Business Majors is 28.16. This indicates that business major students in this study view unethical behaviors as more acceptable compared to their non-Business major counterparts.

Results of Hypotheses Testing on H5A–Moderating Influence of Course Majors on the TPB Framework

The MLR results tabulated on Table 9 below indicates that TPB applied differently between Business and Non-Business majors. This is evidenced by the difference in slopes for the MLR in both cases indicated by the B-coefficient. As such, H6B is supported indicating that MAJOR is a moderator in the application of TPB to UNETHICAL_BHV.

The model for Business majors is significant at a critical value of 0.05 with the F-Statistic of 5.53. The adjusted R-Squared is 0.13 indicating that the effect size is moderate to large (Cohen 1992). At p < 0.05, EGO and UTIL exerted positive significant relationships with UNETHICAL_BHV. MAGNITUDE and PEER were not significant. Among the significant variables UTIL had the higher explanatory power compared with EGO indicated by the Beta coefficient.

For non-business majors, the model was also significant (F = 5.016; p < 0.05). EGO and UTIL exerted significant positive relationships with UNETHICAL_BHV at the critical values of 0.05 and 0.10 respectively. In addition, MAGNITUDE is also significant at p < 0.10. EGO had the highest explanatory power among the independent variables.

Social Desirability Bias (SDB)

The results of SDB testing in Table 10 below indicate that all the items had a mean of below 3. This indicates that the extent of over-claiming is within acceptable limits.

Discussion of Findings

This study has found that when all respondents were considered, only personal attitudes and magnitude of consequences influence intention towards unethical behavior. Contrary to Azjen’s TPB, peer influence was not a significant predictor of unethical behavior. However, these findings seem to corroborate a similar study in California who found that subjective norms are the weakest predictor of intention towards unethical behaviour among business students (Wilson 2008).

As Generation Y have been brought up as a technologically savvy and highly reliant on acquiring information through the Internet and other media sources, they may substitute this with the need to consult peers (Curtin et al. 2011). Utilitarianism had the highest explanatory power on unethical behavior. Ethical dilemmas often cause cognitive dissonance between personal values and ethical reasoning (Stone et al. 2009). In line with the overall findings, if the magnitude of consequences increases, there may be strong motivations to create justifications for unethical behaviors. A possible explanation is that Generation Y has been found to be idealistic, value transparent practices and are adverse to conflict (Curtin et al. 2011; Chai et al. 2009). They are more likely to identify discriminatory behavior and workplace misconduct but may be less likely to report them (Ethics Resource Center 2010). As such, they employ utilitarian values and information gathering skills to achieve required consensus.

This study also found that compared to non-business majors, business students seem to ignore magnitude of consequences in making ethical decisions. This raises further red flags especially when corroborated with previous research that found business undergraduates from private universities are less ethically concerned compared with public universities (Lau et al. 2009). Besides, business students have also previously been found to endeavour to achieve social goals being guided more by their perceived individual competence rather than moral values (Giacomo et al. 2011). As these future business leaders will eventually embrace corporate realities, this of concern especially when previous research has also found that Malaysian business managers felt compelled to make ethical compromises due to stiffer competitions, organizational pressures from superiors and lack of clear guidance on the application of ethical codes in complex decisions (Gupta and Sulaiman 1996). These findings raises concerns especially with the greater avenues where greed has been expressed for instance in corporate financial scandals and mismanagement such as Enron and Worldcom (USA), Satyam Computer Services (India) and Transmile, Perwaja Steel, Bumiputra Malaysia Finance and Port Klang Free Trade Zone (Malaysia). The deterioration in rankings in the Corruption Perception Index 2011 may suggest that corruption is more rampant and there are more cases of corruption that there are more cases of corruption that are not reported. Generation Y has been raised amidst high profile financial scandals of the 1990s and 2000s where unethical behaviors in business are often trivialized and justified based on greed and self-interest (Smith and Clark 2010; Treviño and Brown 2004). As such, this study reinforces the critical need to instill healthy personal ethical values among undergraduates who will constitute future leaders of tomorrow.

There was no significant statistical gender difference in unethical behavior in this study however females had a lower mean for unethical behavior as compared to males. This was corroborated by a recent study which found that there were no significant differences in perceptions of law and ethics between gender, age and religion among Generation Y in Malaysia (Thuraisingam and Sivanathan 2012). Generation Y has been described as being a more parent sheltered cohort and this may lead them to have greater tolerance for unethical behaviors (Krowske et al. 2010; Smith and Clark 2010; Nicholas 2009). However, male students tend to be more open to partake in illegal activities. (Lau et al. 2009). Chinese business values have been found to be dominant and widely adopted by other races in Malaysia (Abdul Rashid and Ho 2003). The Chinese business philosophy centers on hard work, pragmatism, face, Guanxi and motivated by prosperity. Gift giving, business reciprocity and favours part of the accepted culture and not considered unethical. This may also have impacted the findings of this study as the sample comprises a majority of Malaysian Chinese students.

When the TPB was applied separately on genders, peer influence and egoism exerted a significant influence on unethical behavior whilst utilitarianism and magnitude of consequences were significant in the case of females. These results corroborated Bateman and Valentine (2010) who found that females are more likely to employ both teleological (consequence) and deontological (rule based) approaches in ethical decision making compared to males who are more inclined towards the former. Males are naturally more achievement and prestige oriented and this may explain the findings of this study (Smith and Clark 2010).

Implications of the Study

Business Ethics (BE) Education

Students of today will constitute future business leaders. The findings of this study that business students are more inclined towards unethical behavior is perturbing and this trend needs to be arrested. A concern was also raised by a previous study that private university students benefitted less from Business Ethics courses compared to counterparts in public university (Saat et al. 2010).

Business decision making involves a combination of personal values, technical knowledge and business awareness. It is not effective to teach business ethics as merely “factual” knowledge or relegate it to the final section of each topic for the sake of academic knowledge (Weber and Gillespie 1998). The purpose of BE courses needs to be one which equips students to make better ethical decisions that would hopefully translate to behavioral changes. In order to do this, BE courses need to focus on applying ethical knowledge to assess real life behavioral scenarios. To this extent, more initiatives are needed to develop case studies and simulation studies that could tease out the complexities of real world ethical business dilemmas. BE principles and discussions need to be integrated into all accounting, finance and management courses. Behavioral changes take time to foster. As such, elements of moral and civic education need to be incorporated across all subjects undertaken in the schooling years (Ryan and Bisson 2011). Even though Moral Studies is offered in primary school, it appears that by itself it has lacked rigour and effectiveness as older students have often been found to be less honest than younger students (Ali et al. 2010). The emphasis of Moral Education needs to be more on instilling positive values and ethical courage rather than merely to pass exams. The purpose of BE should be to create awareness on personal values held and how these may conflict with the business world and to provide a better comprehension on social issues in order to guide ethical decision making.

Private universities could also work with in partnership with accounting professional bodies, corporations and even NGOs to create more business awareness of areas where improvements can be made in the current BE curriculum. Perhaps more activities such as participative dialogues on BE and volunteerism activities can be introduced that enable students to acquire relevant meaning to their knowledge. Students could also be assigned corporate mentors that act as a resource to provide further clarity, relevance and facilitate transition to business in the real world.

Ethical Culture

Malaysia is not short of statutes on practices of corporate governance and organizational ethical codes. However, implementation may be limited to satisfy formal reporting requirements or left to personal conscience. This is repeatedly evident in high profile financial scandals across the globe. Formal ethical codes of conduct at its best provide guidelines but are unlikely to encompass all ethical situations/contexts within a dynamic business environment. Instead an ethical culture needs to be fostered within organizations where individuals share values and meaning of what is acceptable conduct. Ethical culture needs to be built upon a foundation of human governance (Salleh et al. 2009). The concept of human governance views the organization as a natural person where individuals can develop trust and negotiate shared meaning upon which integrity is developed. If unethical behavior is not arrested in the education system, there may be negative externalities which would perpetuate the future workforce.

As Generation Y is characterized as a cohort that increasingly seeks meaning and feedback to work-life, corporate leadership need to set good examples in “walking the talk” and wherever possible engage and assimilate their views in reinforcing the ethical organizational culture. Organizations need to champion change in an ethical manner and continually set new standards of ethical excellence in business education.

Societal Implication

Personal attitudes and values are grounded from childhood and takes time to develop. With the increase in societal affluence parents of Gen Y children may have more resources to provide for their needs and desires to the extent that many have subscribed to over-sheltering their children which have been described as “helicopter” and/or “lawnmower” parents. However, material provisions can never substitute for quality time and parental guidance which is required for social, emotional as well as ethical growth in these youth. Parents need to endeavour to be ethical role models in their lifestyle and provide an environment where youth can also learn from the school of hard knocks. Parents need to realize that tough love may be necessary to develop deeper personal ethical character and values which is much needed for enduring youth development.

Generation Y have been brought up in a society that is increasingly materialistic which may lead to ethical insensitivity or ethical myopia. As such, it is becoming critical for adults (family members, teachers and members of society) to instill and reinforce positive values among youth of today. We should be conscious of the “tidak apa attitude” (Bahasa Malaysia phrase for ethical indifference) and take the lead even in little ways to be role models, mentors and responsible citizens to them.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The sample of this study was limited to undergraduates from a private university and the respondents where the respondents are mostly Malaysian Chinese. As such, it is not generalizable to other populations. Future research could employ the conceptual framework of the study in comparing among working adults, public university undergraduates and cross-cultural samples. This study investigated ethical intentions and assumes that this will reflect actual ethical behaviors. Future research could extend this to investigation of actual behaviors. We would also suggest that the constructs of TPB be studied together with religiousity and other demographic variables such as year of study, age, ethnicity and family background.

Conclusion

This study investigated the application of the TPB in addressing unethical intentions among Generation Y in Malaysia. Overall, the findings showed that personal attitude dimensions (egoism and utilitarianism) and magnitude of consequences exerted significant influence on unethical behavior intentions. However, peer influence is not significant. When analyzed in terms of gender, unethical behaviors among males were found to be influenced by peer influence and egoism whereas for females, the antecedents were magnitude of consequences and utilitarianism. Methodologically, the study developed valid instruments for the study. Social desirability bias was also controlled via an adaptation of the Crowne and Marlowe (1960) concept.

Generation Y are fast advancing to the workforce and assuming the role of leaders of tomorrow. They are characterized as an Internet savvy cohort, possess self-confident in their competencies, idealistic and constantly searching for meaning in what they undertake. The findings of this study suggest that their self-confidence and achievement attitudes may surpass their perceived need for peer support when making ethical decisions. Compared to non-business majors, business students were found to be more unethical and appeared to ignore magnitude of consequences. As such, there is a critical need to review and enhance the state and role of business ethics education, build ethical culture in organizations as well as create awareness of the role of society in the ethical development of youth in Malaysia.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Ong Teng Wuen, Gan Meng Hoi, Eu Kah Mun and Lim Jen Jean for the support in the course of the research.

References

Abdul Rashid, M. Z., & Ho, J. A. (2003). Perception of business ethics in a multicultural community: the case of Malaysia. Journal of Business Ethics, 43, 75–87.

Ahmad, N. H., Ansari, N. A., & Aafaqi, R. (2005). Ethical reasoning: the impact of ethical dilemma, egoism and belief in just world. Asian Academy of Malaysian Journal, 10(2), 81–101.

Ajzen, I. (1991). Theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Alam, S. S., Ahmad, A., Ahmad, M. S., & Nik Hashim, N. M. H. (2011). An empirical study of an extended theory of planned behavior model for pirated software purchase. World Journal of Management, 3(1), 124–133.

Ali, K. K., Salleh, R., & Sabdin, M. (2010). A study on the level of ethics at a Malaysian private higher learning institution: comparison between foundation and undergraduate technical-based students. International Journal of Basic and, Applied Statistics, 10(8), 35–49.

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned baheviour: a meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 471–499.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self–efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147.

Barnett, T. (2001). Dimensions of moral intensity and ethical decision making: an empirical study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(5), 1038–1057.

Barnett, T., Bass, K., & Brown, G. (1994). Ethical ideology and ethical judgment regarding ethical issues in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(6), 469–469.

Barnett, T., Brown, G., & Bass, K. (1994). The ethical judgments of college students regarding business issues. The Journal of Education for Business, 69(6), 333–338.

Bateman, C. R., & Valentine, S. R. (2010). Investigating the effects of gender on consumers’ moral philosophies and ethical intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 393–414.

Beltramini, R., Peterson, R., & Kozmetsky, G. (1984). Concerns of college students regarding business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 3, 195–200.

Bowes-Sperry, L., & Powell, G. N. (1999). Observers’ reactions to social-sexual behavior at work: an ethical decision making perspective. Journal of Management, 25(6), 779–802.

Buchan, H. F. (2005). Ethical decision making in the public accounting profession: an extension of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 61, 165–181.

Bushe, S., & Gilbertson, D. (2007). Business ethics: where philosophy and ethics collide. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability, 3(2), 1–34.

Butterfield, K. D., Trevino, L. K., & Weaver, G. R. (2000). Moral awareness in business organisations: influences of issue-related and social context factors. Human Relations, 53(7), 981–1018.

Carol, Y. Y. L. (1999). Business ethics in Taiwan: a comparison of company employees and university student. Business and Professional Ethics Journal, 18(2), 69–90.

Carrell, S. E., Malmstorm, J. E., & West, J. E. (2007). Peer effects in academic cheating. Journal of Human Resource, 43(1), 173–207.

Chai, L. T., Lung, C. K., & Ramly, Z. (2009). Exploring ethical orientation of future business leaders in Malaysia. International Review of Business Research Paper, 5(2), 109–120.

Chan, S. Y. S., & Leung, P. (2006). The effects of accounting students’ ethical reasoning and personal factors on their sensitivity. Managerial Auditing Journal, 21(4), 436–457.

Chang, M. K. (1998). Predicting unethical behavior: a comparison of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 1825–1834.

Chen, M., Pan, C., & Pan, M. (2009). The joint moderating impact of moral intensity and moral judgment on consumer’s use intention of pirated software. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 361–373.

Cheong, C. K. (1999). Ethical judgment and ethical reasoning: a cross-lag model for university students in Hong Kong. College Studies Journal, 33(4), 515–534.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Conner, M., & Armitage, C. J. (1998). Extending the theory of planned behavior: a review of avenues for future research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(15), 1429–1464.

Cox, T. (2009). Business students cheat more often than others. The Badger Herald http://badgerherald.com/news/2009/02/11/study_business_stude.php. Accessed 3 June 2011.

Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2004). Questioning the domain of the business ethics curriculum. Journal of Business Ethics, 54, 357–369.

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24(4), 349–354.

Crutchfield, R. S. (1955). Conformity and character. American Psychologist, 10(1), 191–198.

Curtin, P. A., Gallicano, T., & Matthews, K. (2011). Millennials’ approaches to ethical decision making: a survey of young public relations agency employees. The Public Relations Journal, 5(2), 1–22.

d’Astous, A., Colbert, F., & Montpetit, D. (2005). Music piracy on the web- how effective are anti-piracy arguments: evidence from the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Consumer Policy, 28, 289–310.

Debeljak, J., & Krkac, K. (2008). “Me, myself & I”: practical egoism, selfishness, self-interest and business ethics. Social Responsibility Journal, 4(1), 217–227.

Devinney, T. M. (2010). The consumer, politics and everyday life. Australasian Marketing Journal, 18(3), 190–194.

Dharan, B. G., & Bufkins, W. R. (2008). Red flags in Enron’s reporting of revenues & key financial measures, http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~bala/files/dharan-bufkins_enron_red_flags.pdf. Accessed 8 August 2012.

Dukerich, J. M., Waller, M. J., George, E., & Huber, G. P. (2000). Moral intensity and managerial problem solving. Journal of Business Ethics, 24(1), 29–38.

Eisend, M., & Schubert-Güler, P. (2006). Explaining counterfeit purchases: a review and preview. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 2006, 1(1). http://search.proquest.com/docview/200799861?accountid=40355 Accessed 3 August 2012.

Elias, R. Z., & Faraj, M. (2010). The relationship between accounting students’ love for money and their ethical perception. Managerial Auditing Journal, 25(3), 269–281.

Ethics Resource Center (2010). 2009 National business ethics survey: Millennials, Gen X and Baby Boomers: who’s working at your company and what do they think about ethics? http://ethics.org/files/u5/Gen-Diff.pdf Accessed 15 April 2012.

Fieser, J. (2009). Ethics. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://www.iep.utm.edu/ethics/#SSH1b.i Accessed 8 May 2011.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Flannery, B. L., & May, D. R. (2000). Environmental ethical decision making in the U.S. metal-finishing industry. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 642–662.

Ford, R. C., & Richardson, W. D. (1994). Ethical decision making: a review of the empirical literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 205–221.

Franke, G. R., Crown, D. E., & Spake, D. E. (1997). Gender differences in ethical perception of business practices. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 920–934.

Frey, B. (2000). The impact of moral intensity on decision making in a business context. Journal of Business Ethics, 26(3), 181–195.

Fukukawa, K. (2002). Developing a framework for ethically questionable behavior in consumption. Journal of Business Ethics, 41, 99–119.

Giacomo, D. E., Brown, J., & Akers, M. D. (2011). Generational differences of personal values of business students. American Journal of Business Education, 4(9), 19–30.

Gill, S. (2010). Is gender inclusivity an answer to ethical issue in business?: an Indian stance. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25(1), 37–63.

Gino, F., Ayal, S., & Ariely, D. (2009). Contagion and differentiation in unethical behavior: the effect of one bad apple on the barrel. Journal of the Association of Psychological Science, 20(3), 393–398.

Granitz, N., & Loewry, D. (2007). Applying ethical theories: interpreting and responding to student plagiarism. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 293–306.

Gupta, J. L., & Sulaiman, M. (1996). Ethical orientations of managers in Malaysia. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 735–748.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). USA: Pearson.

Harrington, S. (1997). A test of a person issue contingent model of ethical decision making in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(4), 363–375.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organisations: an issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

Jones, G. E., & Kavanagh, M. J. (1996). An experimental examination of the effects of individual and situational factors on unethical behavioral intentions in the workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 511–523.

Kakabadse, N. K., Kakabadse, A., & Kouzmin, A. (2002). Ethical considerations in management research: a ‘truth’ seeker’s guide. International Journal of Value–Based Management, 15(2), 105–138.

Kay, C. D. (1997). Varieties of egoism. http://webs.wofford.edu/kaycd/ethics/egoism.htm Accessed 8 May 2011.

Kevin, J. (2010). The scandal beneath the crisis: getting a view from a cultural-moral mental model. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, 33(2), 735–778.

Kirkpatrick, J. (2002). A critique of “is business bluffing ethical?” Marketing Educators’ Association Conference, 21st April 2002, San Diego. http://www.csupomona.edu/~jkirkpatrick/Papers/CritBluff.pdf Accessed 11 August 2012.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Trevino, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1–31.

Klein, H. A., Levenburg, N. M., & Mothersell, W. (2006). Cheating during the college years: how do business school students compare. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 197–206.

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Krowske, B. J., Rasch, R., & Wiley, J. (2010). Millennials’ (lack of) attitude problem: an empirical examination of generational effects on work attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 265–279.

Lane, J. C. (1995). Ethics of business students: some marketing perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 14, 571–580.

Lau, T. C., Choe, K. L., & Ramly, Z. (2009). Exploring ethical orientations of future business leaders in Malaysia. International Review of Business Research Papers, 5(2), 109–120.

Li, J., Mizerski, D., Lee, A., & Liu, F. (2009). The relationship between attitude and behavior: an empirical study in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 21(2), 232–242.

Lincoln, S. H., & Holmes, E. K. (2010). The psychology of making ethical decisions: what affects the decision? Psychology Services, 7(2), 57–64.

Macdonald, J. E., & Beck-Dudley, C. L. (1994). Are deontology and teleology mutually exclusive? Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 615–623.

Mahmud, S. N. D., & Osman, K. (2010). The determinants of recycling intention behavior among the Malaysian school students: an application of theory of planned behaviour. Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 119–124.

Manski, C. F. (1993). Identification and endogenous social effects: the reflection problem. Review of Economic Studies, 60(3), 531–542.

Mat Norwani, N., Mohamad, Z. Z., & Chek, I. T. (2011). Corporate governance failure and impact on financial reporting within selected companies. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(21), 205–213.

May, D. R., & Pauli, K. P. (2002). The role of moral intensity in ethical decision making: a review and investigation of moral recognition, evaluation and intention. Business Society, 41(1), 84–117.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Cheating in academic institutions: a decade of research. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 209–232.

McLean, P. A., & Jones, D. G. B. (1992). Machiavellianism and business education. Psychological Reports, 71, 57–58.

McMahon, J. M., & Harvey, R. J. (2006). An analysis of the factor structure of Jones’ moral intensity construct. Journal of Business Ethics, 64, 381–404.

McMahon, J. M., & Harvey, R. J. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Reidenbach–Robin multidimensional ethics scale. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 27–39.

Modarres, A., & Rafiee, A. (2011). Influencing factors on the ethical decision making of Iranian accountants. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(6), 136–144.

Mokhtar, R., Othman, A., Zainuddin, Y. (2010). Psychological characteristics and entrepreneurial intention among Polytechnic students in Malaysia: a theory of planned behavior approach. In The first seminar on: entrepreneurship and societal development in Asean (ISE-SODA 2010) “Achieving Regional Growth through Entrepreneurship Education”, 27th February–1st March 2010, City Bayview Hotel Langkawi. ASEAN Universities Consortium of Entrepreneurship Education (AUCEE), 55–69.

Molnar, K. K., Kletke, M. G., & Chongwatpol, J. (2008). Ethics vs. IT ethics: do undergraduate perceive a difference. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 657–671.

Morris, S., & McDonald, R. (1995). The role of moral intensity in moral judgments: an empirical investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 14(9), 715–726.

Nantel, J., & Weeks, W. A. (1996). Marketing ethics: is there more to it than the utilitarian approach? European Journal of Marketing, 30(5), 9–19.

Nicholas, A. J. (2009). Generational perceptions: workers and consumers. Journal of Business and Economics Research, 7(10), 47–52.

Noordin, M. F., & Sadi, A. H. M. S. (2010). The adoption of mobile commerce in Malaysia: an exploratory study on the extension of theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Analyst, 31(1), 1–30.

Owens, D. (1998). From the business ethics course to the sustainable curriculum. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 1765–1777.

Paulhus, D. L., Harms, P. D., Bruce, M. N., & Lysy, D. C. (2003). The over-claiming technique: measuring self-enhancement independent of ability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 890–904.

Pauli, K. P., & May, D. R. (2002). Ethics and the digital dragnet: magnitude of consequences, accountability, and the ethical decision making of information systems professionals. Academy of Management Proceedings, http://www.slis.indiana.edu/faculty/hrosenba/www/l574/pdf/pauli_ethics-it.pdf Accessed 11 June 2011.

Pearsall, M. J., & Ellis, A. P. J. (2011). Thick as thieves: the effects of ethical orientation and psychological safety on unethical team behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 401–411.

Peterson, R. (1994). A meta-analysis of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(2), 381–391.

Phillips, D. L., & Clancy, K. J. (1972). Some effects of “social desirability” in survey studies. The American Journal of Sociology, 77(5), 921–940.

Rainbow, C. (2002). Descriptive of ethical theories and principles, http://www.biodavidson.edu/people/kaberndep/carainbow/Theories.html Accessed 1 June 2011.

Randall, D. M. (1994). Why students take elective business ethics courses: applying the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 369–378.

Rest, J. R. (1986). Moral development: Advances in research and theory. New York: Praeger.

Ryan, T. G., & Bisson, J. (2011). Can ethics be taught? International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(12), 44–52.

Saat, M. M., Jamal, N. M., Othman, A. (2004). Lecturer’s and student’s perception on ethics in academic and lecturer’s-student interaction. Research Management Centre, http://eprints.utm.my/2745/1/71989.pdf Accessed 4 June 2011.

Saat, M. M., Porter, S., & Woodbine, G. (2010). An exploratory study of the impact of Malaysian ethics education on ethical sensitivity. Journal of Business Ethics Education, 7, 39–62.

Salleh, A., Ahmad, A., & Kumah, N. (2009). Human governance: a neglected mantra for continuous performance improvement. Performance Improvement, 48(9), 26–30.

Sautter, J. A., Brown, T. A., Littvay, L., Sautter, A. C., & Bearness, B. (2008). Attitude and divergence in business students: an examination of personality differences in business and non-business students. EBO Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies, 13(2), 70–78.

Securities Commission (2012). Malaysian code on Corporate Governance 2012, http://www.sc.com.my/eng/html/cg/cg2012.pdf Accessed 11 August 2012.

Sedmak, S., & Nastav, B. (2010). Perception of ethical behavior among business studies student. 11th International Conference on Social Responsibility, Professional Ethics and Management, 24–27 November 2010, Ankara, Turkey.

Shaver, R. (2010). Egoism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2010/entries/egoism/ Accessed 23 April 2012.

Shaw, W. H., & Barry, V. (2010). Moral issues in business (11th ed.). Canada: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Sikula, A., & Costa, A. (1994). Are women more ethical than men? Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 859–871.

Singer, M., Mitchell, S., & Turner, J. (1998). Consideration of moral intensity in ethicality judgments: its relationship with whistle blowing and need-for-cognition. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(5), 527–541.

Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., & Franke, G. R. (1999). Antecedents, consequences, and mediating effects of perceived moral intensity and personal moral philosophies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(1), 19–35.

Singhapakdi, A., Karande, K., Rao, C. P., & Vitell, S. J. (2001). How important are ethics and social responsibility? a multinational study of marketing professionals. European Journal of Marketing, 5(1/2), 133–152.

Smith, H. (2010). Measuring the consequences of rules. Utitas, 22(4), 413–434.

Smith, J. W., & Clark, G. (2010). New games, different roles- Millennials are in town. Journal of Diversity Management, 1(3), 1–11.

Smith, K. J., Davy, J. A., Rosenberg, D. L., & Haight, G. F. (2009). The role of motivation and attitude on cheating among business students (pp. 12–37). Ethics: Journal of Academic and Business.

Sommer, L. (2005). The theory of planned behavior and impact on past behavior. The International Business & Economics Research Journal, 10(1), 91–110.

Stone, T. H., Jawahar, I. M., & Kisamore, J. L. (2009). Using the theory of planned behavior and cheating justifications to predict academic misconduct. Career Development International, 14(3), 221–241.

Sutherland, E. H. (1983). White collar crime: The uncut version. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sweeney, B., & Costello, F. (2009). Moral intensity and ethical decision-making: an empirical examination of undergraduate accounting and business students. Accounting Education: An International Journal, 18(1), 75–97.

Thoma, S. J. (1986). Estimating gender differences in the comprehension and preference of moral issues. Developmental Review, 6(2), 165–180.

Thompson, E. R., & Phua, F. T. T. (2005). Reliability among senior managers of the Marlowe-Crowne short-form social desirability scale. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(4), 541–553.

Thuraisingam, A. S., & Sivanathan, P. (2012). Gxeneration Y’s perception towards law and ethics. Journal of Advanced Social Research, 2, 52–66.

Transparency International (2011). Surveys and indices: corruption perception index, http://www.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/cpi Accessed 23 April 2012.

Treviño, L. K., & Brown, M. E. (2004). Managing to be ethical: debunking five business ethics myth. The Academy of Management Executive, 18(2), 69–81.

Trevino, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: a review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990.

Tsalikis, J., & Ortiz-Buonafina, M. (1990). Ethical beliefs’ differences of males and females. Journal of Business Ethics, 9, 509–517.

Vanasco, R. R. (1998). Fraud auditing. Managerial Auditing Journal, 13(1), 4–71.

Weber, J. (1996). Influences upon managerial moral decision making: nature of the harm and magnitude of consequences. Human Relation, 49(1), 1–22.

Weber, J., & Gillespie, J. (1998). Differences in ethical beliefs, intentions and behaviors: the role of beliefs and intentions in ethics research revisited. Business and Society, 37(4), 447–467.

Wilson, B. A. (2008). Predicting intended unethical behavior of business students. Journal of Education for Business, March/April, 187–194.

Woiceshyn, J. (2011). A model for ethical decision making in business, reasoning, intuition and rational moral principle. Journal of Business Ethics, 104, 311–323.

Wyld, D. C., & Jones, C. A. (1997). Importance of context. The ethical work climate construct and models of ethical decision-making–an agenda for research. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 465–472.

Zabid, A. R. M., & Alsagoff, S. K. (1993). Perceived ethical values of Malaysian managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 12, 331–337.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nga, J.K.H., Lum, E.W.S. An Investigation into Unethical Behavior Intentions Among Undergraduate Students: A Malaysian Study. J Acad Ethics 11, 45–71 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-012-9176-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-012-9176-1