Abstract

The present study aimed at investigating the status of cheating on exams in the Iranian EFL context. One hundred thirty two university students were surveyed to this end. They were selected through convenient sampling. The results indicated that cheating is quite common among the Iranian language students. The most important reasons for this behavior were found to be “not being ready for the exam”, “difficulty of the exam”, “lack of time to study” and “careless and lenient instructors”. The study also indicated that the most common methods of cheating are “talking to the adjacent individuals”, “copying from others' test papers”, and “using gestures to get the answers from others”. It was also found that the student’s field of study, academic level, and occupational status had a significant effect on cheating whereas gender and marital status had no effect in this regard. Furthermore, it became clear that field of study and occupational status had a significant effect on students’ attitude toward cheating whereas gender, academic level and marital status had no effect. Finally, the study indicated that age significantly correlated with cheating and attitude toward cheating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The last few decades have seen an increasing interest in studying student academic dishonesty (Nazir and Aslam 2009). The rise of interest may come from the fact that academic dishonesty has been on the increase in different contexts. There is a great deal of research indicating that academic dishonesty in the form of cheating is quite prevalent in the academic context (Al-Qaisy 2008; Collison 1990; Faulkender et al. 1994; Graham et al. 1994; Klein et al. 2007; Lim and See 2001; McCabe and Trevino 1997; McCabe and Trevino 1993; Newstead et al. 1996; Tang and Zuo 1997) and that it has been on the increase recently (Baird 1980; Davis et al. 1992; Diekhoff et al. 1996; Klein et al. 2007; McCabe 2005; McCabe 2001; McCabe and Bowers 1994; Singhal 1982; Tennant and Duggan 2008). This increase has made cheating become a norm and consequently not being viewed as a wrong behavior anymore. (Diekhoff et al. 1996). It has become so common that Alschuler and Blimling (1995) speak of epidemic cheating. Faulkender et al. (1994) also state that not only cheating is common but it is also accepted by students as a typical behavior. A few studies, however, have found no change in this regard. For example, Brown and Emmett (2001) have found that cheating had not increased during the last 33 years. McCabe and Trevino (1996) have also found it to be more or less a fixed problem with little fluctuation. Some studies have found mixed evidence in this regard. For example, Vandehey et al. (2007) state that cheating has increased in some forms and decreased in others.

A wide range of cheating rates has been reported in a variety of academic contexts. Jendrek (1992) reports a range of 40–90% in this regard. Vandehey et al. (2007) state that a range of 52–90% has been reported in the literature. They themselves came across 57.4%, 61.2% and 54.1%, in a series of studies in 1984, 1994, and 2004 respectively. Jordan (2001) also reports a cheating rate of 31.4%; however, he states that only 8.6% of the students in his study committed 75% of all the acts of exam or paper cheating. Such statistics, he asserts, indicate that cheating is painted blacker than it is. Students’ knowledge of such optimistic statistics can help reduce cheating among them.

Different studies have focused on different aspects of cheating. Many have focused on factors affecting cheating: individual factors, situational factors, and institutional policies. Most of such studies have focused on finding a relationship between cheating and individual factors including gender, age, GPA, academic major, educational level, marital status, occupational status, and motivation.

Concerning gender most of the studies have found that males have a higher tendency to cheat (Al-Qaisy 2008; Baird 1980; Becker and Ulstad 2007; Bowers 1964; Calabrese and Cochran 1990; Crown and Spiller 1998; Davis et al. 1992; Genereux and McLeod 1995; Lim and See 2001; McCabe and Trevino 1997; Michaels and Miethe 1989; Nazir and Aslam 2009; Newstead et al. 1996; Whitley et al. 1999). Some studies, however, have found no difference between males and females (Diekhoff et al. 1996; Fisher 1970; Jordan 2001; Malone 2006; Stevens and Stevens 1987; Vitro and Schoer 1972) and a few others have found that females cheat more (DePalmer et al. 1995; Stern and Havlicek 1986). Crown and Spiller (1998) also state that gender effect, if any, is decreasing.

Unlike gender, more consistent results have been found concerning age. Studies in this regard have found a negative relationship between age and cheating; that is, younger students tend to cheat more than the older students (Antion and Michael 1983; Coombe and Newman 1997; Diekhoff et al. 1996; Graham et al. 1994; Klein et al. 2007; Newstead et al. 1996; Vandehey et al. (2007); Whitley 1998). Barger et al. (1998) state that younger students have their own code of ethics that base their behavior, but as they grow up they demonstrate more moralities in their behaviors and become more philosophical. There are only a few studies which are not consistent with such a finding. For example, Tang and Zuo (1997) found higher rates of cheating for older students and Nazir and Aslam (2009) found no specific pattern for the effect of age in different age groups.

As for GPA, most of the studies have found a negative relationship with cheating (Crown and Spiller 1998; Klein et al. 2007; Nazir and Aslam 2009; Smith et al. 2002; Vandehey et al.(2007) although a few like Jordan (2001) have found no difference in cheating rates based on GPA.

The studies conducted on the relationship between academic major and cheating are not consistent at all. On the one hand, there are studies that speak of the role that major plays in cheating. For example, they report that business students cheat more than other students (Baird 1980; Caruana et al. 2000; Christine and James 2008; Clement 2001; Harris 1989; McCabe and Trevino 1995; Smyth and Davis 2004); and that students in humanity faculties cheat more due to the nature of the courses they pass which basically demands memorization (Al-Qaisy 2008). On the other hand, there exist some studies that report no difference between different majors in terms of cheating (Beltramini et al. 1984; Klein et al. 2007; Jordan 2001). Regarding this, Borkowski and Ugras (1998) reviewed 30 studies conducted on the relationship between major and cheating and found that the majority of the studies had found non-significant differences between different majors.

Concerning the level of education, most of the studies have found a negative relationship with cheating. For instance, Jordan (2001) found that 1st year students cheated significantly more than juniors and seniors. Similar findings have been found by other studies indicating that undergraduates cheat more (Diekhoff et al. 1996; Haines et al. 1986; Graham et al. 1994; Nazir and Aslam 2009; Rakovski and Elliott 2007; Whitley et al. 1999). However, a number of studies have found no significant relationship in this regard (Al-Qaisy 2008, Christine and James 2008; Zastrow 1970).

Concerning the marital status, more tendencies have been found in single students to cheat (Vandehey et al. 2007; Whitley 1998).

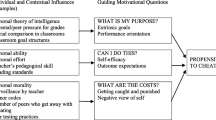

Other factors studied in their relation to cheating include motivation (Jordan 2001; Kibler and Kibler 1993; Tang and Zuo 1997) and self-esteem (Anderman et al. 1998; Anderman and Midgley 1997; Dweck 1986; Dweck and Leggett 1988; Newstead et al. 1996).

While many studies have focused on the role that individual characteristics play in cheating, a number of studies have focused on the situational factors affecting cheating, and fewer studies have also investigated the role of institutional policies in academic dishonesty in general and cheating in particular. As for the situational factors, the effect of peers is the most investigated factor which has been indicated to exert a strong influence on students’ academic honesty. It has been found that peers’ behaviors and attitudes have a noticeable impact on the cheating committed by others (Graham et al. 1994; Kibler and Kibler 1993; Stevens and Stevens 1987). In the same line, Jordan (2001) found that students committed more cheating as the result of exposure to the cheating of others. Moreover, more cheaters in his study reported having seen someone cheat than did non-cheaters. A more interesting finding in this regard was that peer disapproval turned out to be the strongest predictor of reduced cheating behavior (Genereux and McLeod 1995; McCabe and Trevino 1997; McCabe and Trevino 1993). Later on in a similar study McCabe et al. (1999) found that students’ explanations for cheating often include elements of social comparison.

Another situational factor studied in its relation to cheating is the class size. It has been found that students cheat less in smaller classes (Houston 1976; Klein et al. 2007). Coalter et al. (2007), however, found that cheating dropped when the class size was bigger than 50 students. It was speculated that it could be because of the type of assignments in such big classes that cheating dropped.

Concerning the institutional policies, McCabe and Trevino (1993) found a correlation between academic dishonesty and student perceptions of institutional policies. Similar findings are reported by Jordan (2001). McCabe et al. (2001) also state that cheating can most effectively be dealt with at the institutional level.

While the majority of studies have focused on the above-mentioned factors related to cheating, a number of studies have focused on the ways of curbing cheating (e.g. Davis 1993; May and Loyd 1993; McCabe and Trevino 1993). For example, some of these studies have emphasized the role of honor codes in this regard. They have indicated that the appropriate introduction of honor codes can considerably reduce cheating (McCabe et al. 1999; May and Loyd 1993; McCabe and Trevino 1993). McCabe et al. (2001) have also stated that the use of honor codes has been on increase recently. The results of their study suggest that honor codes can have long-term effects on students’ academic behavior. They, however, emphasize that honor codes should not be considered as a panacea that can solve all the problems in every context.

In spite of the preventive role that honor codes play in cheating, some studies have indicated that honor codes are not effective in the absence of other institutional changes (Cole and McCabe 1996; Jendrek 1992; May and Loyd 1993; Vandehey et al. 2007; Whitley and Keith-Spiegel 2001).

Most of the studies conducted on cheating so far have been carried out in developed countries. Few studies have been conducted in an Asian context in developing countries (Nazir and Aslam 2009). Furthermore, it is not clear whether the results of studies in developed countries are also relevant to the Asian context (Lim and See 2001). As such, lack of research is greatly felt in such countries. When it comes to the Iranian context, no study, to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, has been conducted on the academic dishonesty in general and cheating in particular. This was the motive behind the present study to examine the status of cheating in the Iranian EFL (English as a Foreign Language) context. The objectives of the study are multifold: first, it tries to see to what extent Iranian EFL students get engaged in cheating. Second it tries to examine their attitudes toward cheating in the academic context. Third, their explanations and reasons for cheating are explored. Fourth, attempt is made to explore different methods of cheating. And finally, the study tries to see how and if cheating in such a context is related to the individual factors of gender, age, major, educational level, marital status, and occupational status. The following research questions are hence put forward:

-

1.

To what extent do the Iranian language students get engaged in cheating on exams?

-

2.

What are the Iranian language students’ attitudes toward cheating?

-

3.

What are the Iranian language students’ reasons for cheating?

-

4.

What methods do the Iranian language students employ to cheat on exams?

-

5.

Do the Iranian language students’ cheating on exams and their attitude toward cheating differ as far as their gender, field of study, academic level, occupational status, marital status and age are concerned?

Method

Participants

One hundred thirty two language students, 52 males and 79 females took part in the present study. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 36 and were all selected based on their availability and willingness from TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language), and Language and Literature which are the major fields of study usually found in the departments of foreign languages in the Iranian universities.

Instruments

Cheating Questionnaire

A questionnaire was developed to collect information on the students’ cheating in the Iranian academic context. The questionnaire had four short parts; the first part included 3 items that asked the respondents whether they had the habit of cheating on class quizzes, midterm and final exams. The second part of the questionnaire which was designed to survey the students’ attitude toward cheating included 6 items (plus a filler item). Both the first and the second parts were in Likert format with five options to select from (appendix A). The third part of the questionnaire focused on the cheating methods that students employ in their educational life. This part listed 10 of the cheating methods and students were supposed to select from the list the ones they had used before. They were also asked to add to the list if they used other methods not present in the list. The last part of the questionnaire focused on the reasons that students had for their cheating. Like the previous part, here again students were subjected to a list of possible reasons for cheating and were expected to specify the ones they thought could explain their cheating. If they had other reasons not in the list, they were asked to add them to the list.

All the sections of the questionnaire were designed after careful analysis of the literature. Furthermore, the researcher interviewed a number of language students and professors about cheating, methods of doing it and the reasons behind it. Getting insights from the literature and the faculty and students’ ideas, the questionnaire was finally developed in the Likert format. It was prepared in students’ native language (Persian) to avoid any misunderstanding. A translated copy of the questionnaire in English; however, appears in the appendix.

Data Collection and Analysis

The data for this study were collected through distributing the cheating questionnaire. Students from different universities took part in the study through emails. Some students were also given the questionnaire by the researcher in person. The questionnaire was given in students’ native language to avoid any probable misunderstanding.

A series of t-test and correlational procedures was utilized to analyze the collected data in terms of the students’ attitudes toward, reasons for, and methods of cheating on exams and also to see whether and to what extent cheating correlated with such factors as gender, age, field of study, academic level, marital status and occupational status.

Results of the Study

Results for the Students’ Cheating on Exams

Research Question 1: To What Extent Do the Iranian Language Students Get Engaged in Cheating on Exams?

The first part of the questionnaire asked students if they cheat on academic exams like quizzes, midterm and final exams. Table 1 depicts the descriptive statistics in this regard. It indicates the occurrence of this academic misconduct among the Iranian university students. As depicted 28.78% of the students have stated that they cheat on class quizzes, 24.99% have said that they cheat on midterm exams and 24.24% have stated that they cheat on final exams.

Research Question 2: What Are the Iranian Language Students’ Attitudes toward Cheating?

Concerning the attitudes toward cheating, Table 2 depicts the results. It is depicted that 40.90% of the participants believe that cheating is an easy thing to do. 9.84% believe that you have to cheat to achieve what you deserve to and that if you do not cheat you are a loser (24.23%). It is interesting to see that 35.60% believe that cheating is a normal behavior and that you should cheat on exams because this is what you also need in your real life as well (18.98%). The last finding which is quite shocking is that 19.69% enjoy cheating and do it for fun.

Research Question 3: What Are the Iranian Language Students’ Reasons for Cheating?

Regarding the reasons for cheating, the results are indicated in Table 3. More than 60% have stated that “not being ready for the exams” is the reason for their cheating. About half of the students believe that “the difficulty of the test” and “lack of time to study” could make them cheat on their exams. Carless and lenient proctors, having stress at the time of the exam, not being sufficiently motivated to study, equal treatment of the cheaters and non-cheaters are all other reasons mentioned for cheating in the order of priority. At the lower levels it can be seen that about a quarter of the students believe that “absence of severe punishment for the cheaters” is a reason for cheating. A similar finding is found for the “pressure or encouragement on the part of classmates” to cheat. A shocking finding is that about 25% believe that people may commit cheating only for the fun of it. Finally, 22.72% have stated “following the example of others” as a reason for cheating. Overall, it can be seen that all the reasons for cheating are selected by more than 20% of the participants.

Research Question 4: What Methods Do the Iranian Language Students Employ to Cheat on Exams?

Table 4 below demonstrates the results for the methods that Iranian language students usually employ to cheat on exams. It indicates that all the 10 methods mentioned in the questionnaire are used at least by some students. The most common method, as indicated in the table, is “looking at and copying from others’ test papers”. This is a technique used by more than half of the students. “Talking to the adjacent individuals” and “using gestures to get the answers from others” are the second and third most common methods of cheating. An interesting finding is that some students use cell phones to cheat on the exams by sending messages (25%) or by using the Bluetooth system to send the answers to their classmates (19.69%). It can be seen that the least frequent method is used by about 20% of the participants. This means that the students are familiar with all the methods and may employ different methods based on the context.

However, it should be mentioned that not all the students took advantage of all of these cheating methods. The majority of the students (72.31%) have been involved in cheating in general. 15.38% have got engaged in only one type of cheating behavior; 16.92% in 2 types; 11.54% in 3 types; 14.62% in 4 to 9 different types; and 13.85% have tried all the ten types of cheating behavior. Only 27.69% have not been involved in any type of cheating.

Results for the Factors Affecting Cheating

Research Question 5: Do the Iranian Language Students’ Cheating on Exams and Their Attitude toward Cheating Differ as Far as Their Gender, Field of Study, Academic Level, Occupational Status, Marital Status and Age Are Concerned?

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics for the factors affecting the cheating on academic exams.

The lowest difference depicted in this table is for the effect of gender; that is, both male and female students seem to have the same behavior toward cheating on exams. However, for the other factors some more noticeable differences are depicted. To see whether the differences found were statistically significant or not, a series of independent t-tests was run. Table 6 indicates the results in this regard.

It can be understood from Table 6 that the differences depicted in Table 5 are statistically significant as far as field of study, academic level, and occupational status are concerned, whereas the differences for gender and marital status are not statistically significant. The results of these two tables overall indicate that Literature students cheat more than TEFL students; that BA students cheat more than MA students; and finally that jobless students cheat more than employed students. The eta squared statistics indicate moderate effects for the three factors (field = .09, academic level = .07, occupational status = .07).

The last finding concerning the cheating on exams is related to the factor of age. Table 7 below indicates that there exists a negative correlation between cheating and age; that is, language students tend to cheat less as they grow older. Of course the correlation depicted in this regard is low, though significant, based on Cohen (1988).

Results for the Factors Affecting the Attitude toward Cheating

Research Question 5: Do the Iranian Language Students’ Cheating on Exams and Their Attitude toward Cheating Differ as Far as Their Gender, Field of Study, Academic Level, Occupational Status, Marital Status and Age are Concerned?

Table 8 presents the results of the study for the attitude toward cheating as far as the factors of gender, field of study, academic level, marital status, and occupational status are concerned.

The Table demonstrates similar results for male and female students; however, for the other factors the differences depicted seem to be more noticeable. To see the statistical significance of the differences, a number of independent t-tests were employed.

Table 9 indicates that the differences found in this regard are statistically significant based on the participants’ field of study and occupational status, but the differences found for the factors of gender, academic level and marital status are not statistically significant. In other words students hold the same idea toward cheating regardless of being male or female, single or married, and Literature or TEFL students.

Finally, the correlation found between age and the attitude toward cheating was significant, meaning that students of different ages hold different ideas toward cheating. Of course the correlation found in this regard is low, though significant, based on the criterion put forward by Cohen (1988).

Discussion

This study aimed at investigating the status of cheating in the Iranian academic context. It came up with the finding that cheating is quite common among the Iranian language students. It was found that about a quarter of the students cheat on midterm and final exams, though the number of those who cheat on class quizzes is a bit larger (28.78%). In other words one out of every four Iranian language students cheats on the academic exams like midterm and final exams or class quizzes. This finding is in line with McCabe and Trevino (1996) who found that 70% of the students cheat on exams. McCabe (1999) also found that 82% of the students were involved in one or two serious cheating and more than 25% had repetitive test cheating.

That cheating is common among the Iranian university students could first be explained by the attitudes they hold toward this academic misconduct. It was found that 40.90% of the students consider cheating as an easy thing to do. With this in mind, we won’t be surprised to see that cheating is so common among the students. If they think that cheating is easy then they may get tempted to cheat and not to go through the cumbersome way of studying. This temptation increases when we see that considerable number of students do not have a negative idea toward academic cheating. The study found that 35.60% considered cheating as a normal behavior and 24.23% stated that those who do not cheat are harmed. More interesting was the finding that 9.84% believed that cheating is a way to achieve what you deserve to, so it is an academic right. Having such ideas in mind, students can justify their wrong doing and therefore tend to cheat more easily. Some students also associated cheating with their real life and expressed that you need cheating in your academic life because this is what you need in your real life as well (18.98%). This idea explicitly reflects the effect of social factors on education. This is in line with Krsak (2007) who found that 6% of the students considered cheating as a way of life.

Vandehey et al. (2007) studied patterns of cheating in three decades from 1984 to 2004 using the same data collection instruments and procedures. Students’ cheating on exams ranged from 23.75 in 1984 to 23.1% and 20.9% in 1994 and 2004, whereas cheating on quizzes ranged from 22.1% in 1984 to 31.3% and 31% in 1994 and 2004 respectively.

Probably the most interesting finding related to the students’ attitude toward cheating is that 19.69% stated that they enjoyed cheating; that is, for some students probably the only reason for their wrong doing is the fun of it. This could be a personality factor or may be the consequence of inappropriate educational and social norms in the modern society. Today the idea toward cheating has changed. Students seem to believe that getting caught is wrong not the cheating itself (Danielsen et al. 2006; Lathrop and Foss 2000).

Besides the attitudes that can explain students’ cheating on the academic exams, a number of reasons were also expressed by the participants of the study themselves. This information was elicited through the last part of the questionnaire asking the participants to choose their reasons for cheating from the list or to add their reasons to the list. All the reasons were selected by more than 20% of the participants indicating that cheating is a multi-reason action; that is, a student who commits cheating may have more than one reason for doing it and may have different reasons in different contexts. The most important reason mentioned for this wrongdoing was “not being ready for the exam”; that is, many students (60.60%) stated that the basic reason for their wrong doing was that they were not ready for the exam; hence, they had no choice but to resort to cheating in order to pass the test or get a good score.

“Difficulty of the test” was also the second reason mentioned for cheating. When the test is beyond the level of the students they may cheat to deal with this difficulty. This is in line with Ashworth et al. (1997) and Genereux and McLeod (1995) who found that students cheat more when the test is unfair or confusing.

The third reason mentioned is “lack of time to study”. Of course this is in line with reason 1; in fact the first reason is a general one including “lack of time” as well; that is, students may not be ready for a test due to many reasons, one of which is the lack of time to study and get ready. The researcher himself has observed instances of this among the participants who were his students. Some of these students were always grumbling about having lots of materials to read and assignments to do. A few of them very candidly confessed to their cheating saying that they had no choice when they were overwhelmed with the veracity of readings and assignments. This finding is in line with Callahan (2004) who states that heavy course loads are a reason for students’ cheating.

Having “careless and lenient proctors” was also mentioned as one of the main reasons for cheating. More than 40% stated this as a reason for their wrongdoing. When proctors are not careful enough to catch the cheaters or when they are not strict enough with those who are caught, they are, in fact indirectly, encouraging the idea that cheating is not wrong; otherwise, cheaters would have been punished. Closely related to the existence of careless and lenient cheaters are “the absence of severe punishment for cheaters” and “the equal treatment toward cheaters and non-cheaters” which were mentioned by more than 25% of the students as the reasons for their misconduct. This is in line with the literature. Although, the instructor vigilance has been indicated to be a deterrent to cheating (Genereux and McLeod 1995) and that leniency encourages students to cheat (Ashworth et al. 1997; Genereux and McLeod 1995; McCabe et al. 2001; and McCabe et al. 1999) some of the faculty members are not careful enough in this regard.

For instance, Graham et al. (1994) found that 20% of faculty did not watch the students while taking a test and that 26% had no statements about cheating in their syllabus. They also found that 79% of faculty had taken a student cheating but only 9% said they penalized the cheaters. Similarly, Wajda-Johnston et al. (2001) found that in research-oriented universities only 57.2% of the instructors were concerned with cheating and 53% took actions against it. McCabe et al. (2001) also found that students thought that the faculty are not strict enough in dealing with cheating and cheaters. Finally, Diekhoff et al. (1999) found that only 3% of cheaters reported having ever been caught.

It seems that some of the instructors are not careful enough or prefer not to report the students’ cheating to the university (Jendrek 1989; McCabe et al. 2001; Nuss 1984; Singhal 1982; Wright and Kelly 1974) because of lack of administrative support (e.g. Coalter et al. 2007; Roig & Ballew 1994), time constraints, fear of backlash, and misunderstanding of the policies (Roig & Ballew 1994).

For example, McCabe and Trevino (1993) found that faculty prefer to handle the cheating directly and not report the students’ cheating to the university because of the extensive time and energy that one should spend to go through the administrative procedures to document and prove the cheating which sometimes makes the faculty and not the dishonest student appear guilty.

In the same line, Graham et al. (1994) found that faculty did not punish the cheaters who were caught due to: 1. emotional consequences of reacting to cheating such as stress, fear, etc. and 2. The excessive time and efforts that are needed to collect the required evidence in pursuing a charge of cheating.

Similarly, Coalter et al. (2007) found that 82.9% of the faculty believed that taking action against cheaters when caught depended on the adequacy of evidence. They believed that if the act of cheating is only witnessed by the faculty, the student will claim innocent and nothing could be done, therefore it is better for the faculty to ignore it. 12.2% also stated that time is a factor that may reduce taking actions against cheaters.

Finally, Problems in reacting to cheating have made some think that dealing with a cheater is one of the most negative aspects of being a faculty member (Keith-Spiegel et al. 1998).

All of this has certainly had a great role in making cheating become an epidemic dishonesty. As the faculty members get more disappointed in dealing with cheating and cheaters, students become more confident in their cheating and less worried about the consequences of their actions. This is where punishment can play an influential role in decreasing cheating. Genereux and McLeod (1995) and Burns et al. (1998) found that threat of punishment was a top deterrent to cheating. Similarly, Vandehey et al. (2007) emphasizing the role of punishment, express the following as deterrents to cheating: 1. embarrassment of being caught, 2. being dropped by the faculty, 3. fear of the university’s response, 4. fear of receiving F, and 5. Guilt.

Studies have also indicated a high correlation between cheating and students’ perception of the faculty attitude toward cheating. Students cheat less when they perceive that their instructors are careful enough and will react to their cheating (Corcoran and Rotter 1989; Lim and Coalter 2006; McCabe et al. 2001; McLaughlin & Ross 1989; Tom and Borin 1988; Wajda-Johnston et al. 2001; Zelna and Bresciani 2004).

In addition to the lenient instructors, another group of instructors is to be blamed for students’ cheating. Such instructors or teachers are in fact cheaters themselves and have the most influential effect on transferring this idea to students that cheating on exams is a normal behavior and there is nothing wrong with it. In describing such teachers, Rossi and Sweeney (2002 ) state that some teachers are guilty because of a number of improprieties including giving tips during the exam, walking around the class and pointing to the correct answers, erasing the wrong answers and writing the correct answers for the questions that are left blank by the student. The researcher of this paper has also witnessed such behaviors during a decade of teaching in the Iranian high schools. Though the number of such teachers was low, they had their own justification for this wrong doing. They, for example, believed that not all the students have enough time to study. Some of them have to work to help their families manage their living. So they thought such students deserved help on the part of their teachers as due to working they didn’t have time to study and their score was not really representative of their ability. Some other students were benefited by their teachers too: those who had failed a course for two or more succeeding years. Teachers thought these students could not pass a test on their own as probably they did not have the talent to do so or because they couldn’t study well due to many problems. This was especially observed about a decade ago when the educational system was not semester-based. In this system each grade lasted for a year and a student had to get a passing score in all the subject areas before being able to go to higher levels. This meant that even if a student failed in one course, he had to repeat the whole grade with all the courses for one more year, no matter how good he or she was in other courses. Therefore, some teachers thought that this system of education was not fair and tried to help the student who had failed one or two courses to prevent his repeating of all the other courses for one more year. Fortunately, today the educational system has changed. It is semester-based and students only repeat the courses they have failed and they no longer need to repeat the whole program.

Finally, other reasons mentioned by students for cheating were “having stress at the time of the exam”, “not being sufficiently motivated to study”, “pressure or encouragement on the part of the classmates”, “following the example of others”, and “having fun”.

The study also focused on the methods of cheating employed by the students. The majority of the students (72.31%) stated that they were involved in the act of cheating. 15.38% have got engaged in only one type of cheating behavior; 16.92% in 2 types; 11.54% in 3 types; 14.62% in 4 to 9 types; and 13.85% in all the ten types of cheating behavior. Only 27.69% were not involved in cheating. The most common method of cheating was found to be “looking at and copying from others' test papers”. The relevant literature provides evidence for this finding. For example, Genereux and McLeod (1995) found that over 25% of the students in their study shared the exam questions and allowed others to copy from their exam papers. Lim and See (2001) also found that communicating with other students was quite common. They also found that 54.2% copied from neighbors during a quiz without their realizing and that 52.3% used notes. Nazir and Aslam (2009) also report 25% of copying exam sheets; 60% of helping others copy your exam sheet, and 10% of using notes. Similarly, Sims (1995) and Lim and See (2001) found that exam-related cheating including using crib notes was the most serious type of academic dishonesty. Lim and See (2001) report 15.6% of using notes in this regard. Finally, Klein et al. (2007) found that students in their study perceived using unauthorized notes and copying from others’ exam papers as the most conspicuous types of cheating.

Other common methods of cheating used by students included “talking to the adjacent individuals” and “using gestures to get the answers from others” which were the second and third most common methods. The least common methods were also “using a cell phone to Bluetooth the answers” and “exchanging papers with one’s friend's, though even such methods were used by more than 20% of the students”.

A couple of points comes to mind when the results of the study concerning the methods of cheating are examined. It seems that “the existence of careless and lenient proctors” which was mentioned by more than 40% of the students as a reason for their cheating could also be the basic reason for the type of methods used for cheating. Most of the methods mentioned in the questionnaire are very explicit methods that can easily be noticed if the proctors are careful enough. Furthermore, these are very cliché methods that almost everybody knows of; hence, the fact that even the least common methods are used by more than 20% of the students indicates that they feel quite safe in cheating. It also indicates that the cheaters are not worried about the consequences of being caught. All of this means that the instructors are not careful enough in getting the cheaters and are not strict enough in dealing with their cheating.

Concerning the factors affecting cheating, the study indicated that cheating in the Iranian academic context is not influenced by the student’s gender; that is, the students had the same behavior toward cheating regardless of being “male or female”. This finding is in line with (Diekhoff et al. 1996; Fisher 1970; Haines et al. 1986; Jordan 2001; Malone 2006; Stevens and Stevens 1987; Vitro and Schoer 1972) but stands in contrast to many studies which have found that males have a higher tendency to cheat (Al-Qaisy 2008; Baird 1980; Becker and Ulstad 2007; Bowers 1964; Calabrese and Cochran 1990; Crown and Spiller 1998; Davis et al. 1992; Genereux and McLeod 1995; Lim and See 2001; McCabe and Trevino 1997; Michaels and Miethe 1989; Nazir and Aslam 2009; Newstead et al. 1996; Whitley et al. 1999) and a few studies that have found that females cheat more (DePalmer et al. 1995; Stern & Havlicek 1986). In explaining the gender effect, Becker and Ulstad (2007) refer to “risk aversion”. Females may try to avoid the negative consequences of cheating and as such have more tendencies toward ethical behavior. Males, however, are less concerned with ethical issues and therefore may take risk and commit acts of dishonesty. Similar findings are reported by Byrnes et al. (1999) who demonstrated that males are more risk takers in this regard and Tibbetts (1997) who states females usually prefer to avoid shame. McCabe et al. (2006) also state that men may be conditioned to accept less ethical behavior in order to achieve desired results. Similar ideas were previously mentioned by Buckley et al. (1998).

The findings of the present study could, however, be explained by what Ward and Beck (1990) state in the sense that females will also tend to act unethically when they can find some justifications for their breaking of the ethical rules or when they fail to see the consequences of their actions. This will make males and females act similarly with regard to cheating. Many students in the present study believed that their instructors are not careful enough to detect cheating and they are not strict enough with cheaters, so it is not strange that males and females had the same cheating behavior.

As for the marital status, the results were the same as those for gender. No significant difference was found between single and married students in their cheating. This is not in line with the literature as more tendencies have been found in single students to cheat (Haines et al. 1986; Vandehey et al. 2007; Whitley 1998).

The study, however, indicated that the student’s field of study, academic level, and occupational status affect the degree of cheating on academic exams. BA students were found to significantly cheat more than MA students. It should be mentioned that first of all, MA students, due to their higher academic level, are expected to know more about the principles underlying the good academic behavior and observe these principles more than BA students; although one may say that the mere knowledge of the principles may not necessarily lead to more observance of those principles. A second explanation for the lower cheating of MA students can be traced to the effect of age. The present study found that age was significantly and of course negatively related to cheating; meaning that as age increases cheating decreases. Therefore, MA students may cheat less because they are usually older than BA students. As students get older they become more knowledgeable and experienced and tend to observe more of the academic integrity principles. Furthermore, older students seem to have more appreciation for ethics. This is what almost every teacher who has had experience of teaching at different age levels can confirm. The literature also supports this finding. Borkowski and Ugras (1998) in a meta-analysis reviewing several hundred studies came to the point that students become more ethical with age.

Probably, a less pleasant explanation for this finding is related to the size of BA and MA classes in the Iranian universities. Usually BA classes are much more crowded than MA ones. This means that it is more difficult for MA students to cheat. What Sikes (2009) mentions about plagiarism in MA classes could also be extended to their cheating behavior. Sikes (ibid) states that because of the close relationship that exists between the professors and MA students and also due to the supervisory role of the professors, plagiarizing is more difficult for MA students.

The study also indicated that field of study may make a significant difference in cheating. It was found that Literature students cheated more than TEFL students. This finding could be explained through one of the limitations of the present study. Almost all of the TEFL students who took part in the present study were MA students whereas the Literature students were selected from both MA and BA levels. This was because of two reasons. First of all, TEFL is a field that is basically offered at MA and Ph.D. levels in Iran and few universities have TEFL at the BA level. This is in contrast to the Literature which is offered at all BA, MA and Ph.D. levels. Hence, the sample of TEFL students was mostly limited to MA students, whereas the sample of literature students included many BA students as well. This heterogeneity of the samples in terms of the academic level was also to some extent related to the sampling technique used in this study as well. The study employed convenient sampling and this lowered the chance of having BA students of TEFL in the study as BA students of TEFL form a very small population in Iran. Therefore, it seems that what is presented as the result of the field of study is in fact the effect of the academic level.

Another finding of the study was that occupational status significantly affected the degree of cheating. It was found that jobless students cheated more than employed students. This can probably be related to the psychological status of the employed students. Usually employed students are more motivated to study as they have fewer (economic) problems. They are also normally less stressed as they are not worried about their future. Probably such issues overall lead employed students to deal with the exams in a more relaxed and moral ways than jobless students. This finding is in line with Vandehey et al. (2007) who found that cheaters were less likely to have a full-time job, but stands in contrast to Klein et al. 2007 and Becker and Ulstad (2007) who found no difference between the jobless and employed students.

The study also found that gender, academic level and marital status did not significantly affect the students’ attitude toward cheating whereas field of study and occupational status made a significant difference in this regard. It was found that employed students cared more for academic integrity than jobless students. It was also found that Literature students cared less for academic integrity than TEFL students. Of course as mentioned before, this finding seems to be mixed with the effect of the academic level due to the type of sampling.

Finally, the study found that age was also significantly related to the attitude toward cheating. This also makes sense as age was also found to be an important factor in the degree of cheating. The study found that cheating decreased with age as older students tended to cheat less. This means that older students have a more negative idea toward cheating as an academic misconduct and that’s why they also cheat less. This is in line with the findings of many studies reviewed by Borkowski and Ugras (1998). Reese (1998) also states that with an increase in work experiences, one’s understanding of the appropriate and inappropriate behavior also increases.

Conclusion

This study indicated that cheating is quite common among the Iranian language students. It was found that the majority of the students are cheaters and get engage in at least one form of cheating behavior. Different reasons were put forward for this by the students: “not being ready for the exam”, “lack of time to study”, and “difficulty of the test” were among the most important reasons for cheating. The study also indicated that the most common methods of cheating are “talking to the adjacent individuals”, “copying from others' test papers”, and “using gestures to get the answers”. It was’ also found that cheating was not influenced by the student’s gender and marital status but significantly influenced by the field of study, academic level, and occupational status. Age was also found to be significantly related to cheating. Furthermore, the study found that gender, academic level and marital status did not significantly affect the attitude toward cheating whereas field of study and occupational status made a significant difference in this regard. Finally, the study found that age was significantly related to the attitude toward cheating.

The fact that cheating is so common in the Iranian EFL context may lead even good and honest students to take to cheating as they may feel that they are disadvantaged if they are not involved in cheating (McCabe et al. 2001). Another stimulus for cheating could be GPA. In the Iranian educational system GPA plays an important role in students’ getting accepted in higher educational levels. As such, even good students are tempted to cheat as they know that small variations in their GPA may prove to be important in their admission to higher levels.

So what students need to know is that cheating is an exception not a rule that all should follow (McCabe et al. 2001). High school students who enter higher education begin their college or university experience with a positive attitude toward academic honesty, but if they see that higher level students get engaged in cheating and faculty are not strict enough in dealing with such academic dishonesty, “their idealistic view is likely to degenerate rather quickly” (McCabe et al. 2001, p. 230). Therefore, students need education about ethics. They should be taught the principles of academic integrity and be encouraged to follow them. Ethics education has been indicated to have a considerable effect on students’ behavior though for long-term and permanent changes it needs continuous reinforcement (Arlow and Ulrich 1985). Other procedures that can be employed to reduce cheating include high punishment, widely spaced exam seating, using essay exams instead of MC tests (Genereux and McLeod 1995); using alternative forms for tests (Whitley 1998); adequate emphasis on commitment to maintain high academic integrity (Whitley and Keith-Spiegel 2002); and minimizing the bureaucratic complexity of handling cheating (Vandehey et al. 2007).

The best deterrent to cheating, however, seems to be a logical threat of punishment (Alschuler and Blimling 1995; Diekhoff et al. 1996; Genereux and McLeod 1995; Graham et al. 1994; Vandehey et al. 2007). Vandehey et al. (2007) conclude that punitive deterrents have a stronger effect on cheating than internal factors such as feeling of guilt or social deterrents. It should, however, be mentioned that if punishment is too strict, the instructors tend not to use it (Alschuler and Blimling 1995).

Finally, in line with Danielsen et al. (2006) it should be mentioned that changing the current culture of academic dishonesty cannot be much successful unless there are clear policies and appropriate and rapid reactions to any integrity violations. Instructor responsibilities and administrative support work hand in hand to guarantee the examination security.

Limitations of the Study

This study may suffer from the sampling procedure employed in selecting the participants. The study was based on convenient sampling; that is, mostly those students who were volunteers took part in the study. As such, the sample may not necessarily be a representative sample. This may limit the genrelizability of the results to all the Iranian students. Furthermore, the fact that the size of the sample was small could also reduce generelizability and therefore caution is needed in applying the results of the study.

References

Al-Qaisy, L. M. (2008). Students’ attitudes toward cheat and relation to demographic factors. European Journal of Social Sciences, 7(1), 140–146.

Alschuler, A. S., & Blimling, G. S. (1995). Curbing epidemic cheating through systematic change. College Teaching, 43(4), 123–125.

Anderman, E. M., & Midgley, C. (1997). Changes in achievement goal orientations, perceived academic competence, and grades across the transition to middle-level schools. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22, 269–298.

Anderman, E. M., Griesinger, T., & Westerfield, G. (1998). Motivation and cheating during early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 84–93.

Antion, D. L., & Michael, W. B. (1983). Short-term predictive validity of demographic, affective, personal, and cognitive variables in relation to two criterion measures of cheating behaviors. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 43, 467–482.

Arlow, P., & Ulrich, T. A. (1985). Business ethics and business school graduates: A longitudinal study. Akron Business and Economics Review, 16(1), 13–18.

Ashworth, P., Bannister, P., & Thorne, P. (1997). Guilty in whose eyes? University students’ perceptions of cheating and plagiarism in academic work and assessment. Studies in Higher Education, 22(2), 187–203.

Baird, J. S. (1980). Current trends in college cheating. Psychology in the Schools, 17, 515–522.

Barger, R. N, Kubitschek, W. N. and Barger, J. C. (1998). Do philosophical tendencies correlate with personality types? Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA, April 13–17.

Becker, D. A., and Ulstad, I. (2007). Gender differences in student ethics: Are females really more ethical? Plagiary: Cross-Disciplinary Studies in Plagiarism, Fabrication, and Falsification, 77–91.

Beltramini, R. F., Peterson, R. A., & Kozmetsky, G. (1984). Concerns of college students regarding business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 3(1), 195–200.

Borkowski, S. C., & Ugras, U. J. (1998). Business students and ethics: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 7(11), 1117–1127.

Bowers, W. J. (1964). Student dishonesty and its control in college. New York: Bureau of Applied Social Research, Columbia University.

Brown, B. S., & Emmett, D. (2001). Explaining variations in the level of academic dishonesty in studies of college students: Some new evidence. College Student Journal, 35(4), 529–538.

Buckley, M. R., Wiese, D. S., & Harvey, M. G. (1998). An investigation into the dimensions of unethical behavior. The Journal of Education for Business, 73(5), 284–291.

Burns, S. R., Davis, S. F., Hoshino, J., & Miller, R. L. (1998). Academic dishonesty: A delineation of cross-cultural patterns. College Student Journal, 32, 590–596.

Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., & Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 367–383.

Calabrese, R. L., & Cochran, J. T. (1990). The relationship of alienation to cheating among a sample of American adolescents. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 23(2), 65–72.

Callahan, D. (2004). Why more Americans are doing wrong: The cheating culture. Orlando: Harcourt.

Caruana, A., Ramaseshan, B., & Ewing, M. T. (2000). The effect of anomie on academic dishonesty among university students. International Journal of Educational Management, 14(1), 23–29.

Christine, Z. J., & James, C. A. (2008). Personality traits and academic attributes as determinants of academic dishonesty in accounting and non-accounting college majors. Proceeding of the 15th Annual Meeting of American Society of Business and Behavioral Sciences (ASBBS), 15(1), 604–616.

Clement, M. J. (2001). Academic dishonesty: To be or not to be? Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 12(2), 253–270.

Coalter, T., Lim, C. L., and Wanorie, T. (2007). Factors that influence faculty actions: A study on faculty responses to academic dishonesty. International Journal for the Scholar ship of Teaching and Learning, 1(1), 1–21. Retrieved from http://academics.georgiasouthern.edu/ijsotl/2007_v1n1.htm

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cole, S., & McCabe, D. L. (1996). Issues in academic integrity. New Directions in Student Services, 73, 67–77.

Collison, M. N.-K. (1990). Survey at Rutgers suggests that cheating may be on the rise at large universities. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 37(8), A31–33.

Coombe, K., & Newman, L. (1997). Ethics in early childhood field experiences. Journal of Australian Research in Early Childhood Education, 1(1), 1–9.

Corcoran, K. J., & Rotter, J. B. (1989). Morality-conscience guilt scale as a predictor of ethical behavior in a cheating situation among college females. The Journal of General Psychology, 116, 311–316.

Crown, D. F., & Spiller, M. S. (1998). Learning from the literature on collegiate cheating: A review of empirical research. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(6), 683–700.

Danielsen, R. D., Simon, A. F., & Pavlick, R. (2006). The culture of cheating: From the classroom to the exam room. The Journal of Physician Assistant Education, 17(1), 23–29.

Davis, S. F. (1993). Cheating in college is for a career: Academic dishonesty in the 1990’s. Atlanta, Georgia: Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southeastern Psychological Association.

Davis, S. F., Grover, C. A., Becker, A. H., & McGregor, L. N. (1992). Academic dishonesty: Prevalence, determinants, techniques, and punishments. Teaching of Psychology, 19(1), 16–20.

DePalmer, M. T., Madey, S. F., & Bornschein, S. (1995). Individual differences and cheating behavior: Guilt and cheating in competitive situations. Personality and Individual Differences, 18, 761–769.

Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., Clark, R. E., Williams, L. E., Francis, B., & Haines, V. J. (1996). College cheating: Ten years later. Research in Higher Education, 37, 487–502.

Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., Shinohara, K., & Yasukawa, H. (1999). College cheating in Japan and the United States. Research in Higher Education, 40(3), 343–353.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41, 1040–1048.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273.

Faulkender, P. J., Range, L. M., Hamilton, M., Strehlow, M., Jackson, S., Blanchard, E., & Dean, P. (1994). The case of the stolen psychology test: An analysis of an actual cheating incident. Ethics and Behavior, 4, 203–217.

Fisher, C. T. (1970). Levels of cheating under conditions of informative appeal to honesty, public affirmation of value, and threats of punishment. The Journal of Educational Research, 64, 12–16.

Genereux, R. L., & McLeod, B. A. (1995). Circumstances surrounding cheating: A questionnaire study of college students. Research in Higher Education, 36, 687–704.

Graham, M. A., Monday, J., O’Brien, K., & Steffen, S. (1994). Cheating at small colleges: An examination of student and faculty attitudes and behaviors. Journal of College Student Development, 16(2), 777–790.

Haines, V. J., Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., & Clark, R. E. (1986). College cheating: Immaturity, lack of commitment, and the neutralizing attitude. Research in Higher Education, 25, 342–354.

Harris, J. R. (1989). Ethical values and decision processes of male and female business students. The Journal of Education for Business, 64(5), 234–238.

Houston, J. P. (1976). The assessment and prevention of answer copying on undergraduate multiple-choice exams. Research in Higher Education, 5(4), 301–311.

Jendrek, M. P. (1989). Faculty reactions to academic dishonesty. Journal of College Student Development, 30, 401–406.

Jendrek, M. P. (1992). Students’ reactions to student cheating. Journal of College Student Development, 33, 260–273.

Jordan, A. E. (2001). College student cheating: the role of motivation, perceived norms, attitudes and knowledge of institutional policy. Ethics and Behavior, 11, 233–247.

Keith-Spiegel, P., Tabachnick, B. G., Whitley, B. E., Jr., & Washburn, J. (1998). Why professors ignore cheating: Opinions of a national sample of psychology instructors. Ethics and Behavior, 8, 215–227.

Kibler, W. L., & Kibler, P. V. (1993). When students resort to cheating. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 39(45), B1–2.

Klein, H. A., Levenburg, N. M., McKendall, M., & Mothersell, W. (2007). Cheating during the college years: How do business school students compare? Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 197–206. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9165-7.

Krsak AM (2007). Curbing academic dishonesty in online courses. TCC 2007 Proceedings, 159–170.

Lathrop, A., & Foss, K. (2000). Student cheating and plagiarism in the internet era: A wake-up call. Englewood, Colo: Greenwood.

Lim, C. L., & Coalter, T. (2006). Academic integrity: An instructor’s obligation. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 17(2), 155–159.

Lim, V. K. G., & See, S. K. B. (2001). Attitudes toward, and intentions to report, academic cheating among students in Singapore. Ethics and Behavior, 11(3), 261–274.

Malone, F. L. (2006). The ethical attitudes of accounting students. Journal of American Academy of Business, 8(1), 142–146.

May, K. M., & Loyd, B. H. (1993). Academic dishonesty: The honor system and students’ attitudes. Journal of College Student Development, 34, 125–129.

McCabe, A. C., Ingram, R., & Dato-On, M. C. (2006). The business of ethics and gender. Journal of Business Ethics, 64, 101–116.

McCabe, D. L. (1999). National efforts to stem cheating epidemic begins this month. Brown University Child and Adolescent Letter, 15(9), 1–6.

McCabe, D. L. (2001). Cheating: Why students do it and how we can help them stop. American Educator, 25(4), 38–43.

McCabe, D. L. (2005). It takes a village: Academic dishonesty and educational opportunity. Liberal Education, 91(3/4), 26–32.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1993). Academic dishonesty: Honor codes and other contextual influences. Journal of Higher Education, 64, 522–538.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1995). Cheating among business students: A challenge for business leaders and educators. Journal of Management Education, 19(2), 205–218.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1996). What we know about cheating in college: Longitudinal trends and recent developments. Change, 28, 28–34.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1997). Individual and contextual influences on academic dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Research in Higher Education, 38(3), 379–396. EJ547 655.

McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (1999). Academic integrity in honor code and non-honor code environments: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Higher Education, 70, 211–213.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Cheating in academic institutions: A decade of research. Ethics and Behavior, 11(3), 219–233.

McCabe, D. L., & Bowers, W. J. (1994). Academic dishonesty among males in college: A thirty year perspective. Journal of College Student Development, 35(1), 280–291.

McLaughlin, R. D., & Ross, S. M. (1989). Student cheating in high school: A case of moral reasoning vs. “fuzzy logic.”. The High School Journal, 73(3), 97–104.

Michaels, J. W., & Miethe, T. D. (1989). Applying theories of deviance to academic cheating. Social Science Quarterly, 70, 870–885.

Nazir, M. S. and Aslam, M. S. (2009). On the relationship of demography and academic dishonest behaviors of students. Paper presented at the 2nd COMSATS International Business Research Conference, Lahore, Pakistan.

Newstead, S. E., Franklyn-Stokes, A., & Armstead, P. (1996). Individual differences in student cheating. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 229–241.

Nuss, E. M. (1984). Academic integrity: Comparing faculty and student attitudes. Improving College and University Teaching, 32(3), 140–144.

Rakovski, C. C., & Elliott, S. L. (2007). Academic dishonesty: Perception of business students. College Student Journal, 41(2), 466.

Reese, S. (1998). He says it’s okay. American Demographics, 20(6), 36–37.

Roig, M., & Ballew, C. (1994). Attitudes toward cheating of self and others by college students and professors. Psychological Record, 44, 3–12.

Rossi, R., and Sweeney, A. (2002, October 2). Teachers face firing in cheating scandal. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved May 28, 2011, from http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-1460786.html

Sims, R. L. (1995). The severity of academic dishonesty: A comparison of faculty and student views. Psychology in the Schools, 32, 233–238.

Singhal, A. (1982). Factors in students’ dishonesty. Psychological Reports, 51(3), 775–780.

Smith, K. J., Davy, J. A., Rosenberg, D. L., & Haight, G. T. (2002). A structural modeling investigation of the influence of demographic and attitudinal factors and in-class deterrents on cheating behaviors among accounting majors. Journal of Accounting Education, 20(1), 45–65.

Smyth, M. L., & Davis, J. R. (2004). Perception of dishonesty among two-years college students: Academic versus business situation. Journal of Business Ethics, 51(1), 63–73.

Stern, E. B., & Havlicek, L. (1986). Academic misconduct: Results of faculty and undergraduate student surveys. Journal of Allied Health, 15(2), 129–142.

Stevens, G. E., & Stevens, F. W. (1987). Ethical inclinations of tomorrow’s managers revisited: How and why students cheat. The Journal of Education for Business, 63, 24–29.

Tang, S., & Zuo, J. (1997). Profile of college examination cheaters. College Student Journal, 31, 340–346.

Tennant, P., & Duggan, F. (2008). The recorded incidence of student plagiarism and the penalties applied. London: Higher Education Academy.

Tibbetts, S. G. (1997). Gender differences in students’ rational decisions to cheat. Deviant Behavior, 18(4), 393–414.

Tom, G., & Borin, N. (1988). Cheating in academe. The Journal of Education for Business, 1, 153–157.

Vandehey, M., Diekhoff, G., & LaBeff, E. (2007). College cheating: A twenty-year follow-up and the addition of an honor code. Journal of College Student Development, 48(4), 468–480.

Vitro, F. T., & Schoer, L. A. (1972). The effects of probability of test success, test importance, and risk of detection on the incidence of cheating. Journal of School Psychology, 10, 269–277.

Wajda-Johnston, V. A., Handal, P. J., Brawer, P. A., & Fabricatore, A. N. (2001). Academic dishonesty at the graduate level. Ethics and Behavior, 11(3), 287–305.

Ward, D. A., & Beck, W. L. (1990). Gender and dishonesty. Journal of Social Psychology, 130, 333–339.

Whitley, B. E., Jr. (1998). Factors associated with cheating among college students: A review. Research in Higher Education, 39, 235–274.

Whitley, B. E., Jr., & Keith-Spiegel, P. (2001). Academic integrity as an institutional issue. Ethics and Behavior, 11(3), 325–342.

Whitley, B. E., & Keith-Spiegel, P. (2002). Academic dishonesty: An educator’s guide. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Whitley, B. E., Jr., Nelson, A. B., & Jones, C. J. (1999). Gender differences in cheating attitudes and classroom cheating behavior: A meta-analysis. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 41, 657–677.

Wright, J. C., & Kelly, R. (1974). Cheating: Student/faculty views and responsibilities. Improving College and University Teaching, 22, 31–34.

Zastrow, C. H. (1970). Cheating among college graduate students. The Journal of Educational Research, 64(4), 157–160.

Zelna, C. L., & Bresciani, M. J. (2004). Assessing and addressing academic integrity at a doctoral extensive institution. NASPA Journal Online, 42(1), 72–93.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmadi, A. Cheating on Exams in the Iranian EFL Context. J Acad Ethics 10, 151–170 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-012-9156-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-012-9156-5