Abstract

In this study, 40.3% of faculty members admitted to ignoring student cheating on one or more occasions. The quality of past experience in dealing with academic integrity violations was examined. Faculty members with previous bad experiences were more likely to prefer dealing with cheating by ignoring it. The data were further analysed to determine beliefs and attitudes that distinguish between faculty who have never ignored an instance of cheating and those who indicated that they have ignored one or more instances in the past. The stated reasons for ignoring cheating included insufficient evidence, triviality of the offense, and insufficient time; however, it was demonstrated that faculty who ignored academic integrity violations felt more stressed when speaking to students about cheating, preferred to avoid emotionally charged situations, and indicated that if a student were likely to become emotional, they were less likely to speak to him or her.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In April 1801, in the heat of an intense naval conflict during the Battle of Copenhagen, the ship’s signal lieutenant reported to Lord Nelson that the British commander-in-chief’s vessel had raised the flag to “leave off action”—a command to cease fighting. Believing there was opportunity for victory, Nelson is reported to have said, “‘I have only one eye—I have a right to be blind sometimes,’ and then, with an archness peculiar to his character, putting the glass to his blind eye, he exclaimed, ‘I really do not see the signal.’” (Southey 1908) His actions were instrumental in securing an eventual armistice with the Danish Commander (Hibbert 1998). In this instance, Nelson turned a blind eye in order to continue to engage in battle; however, in academia, many faculty turn a blind eye in order to avoid conflict—particularly when it comes to student cheating.

Policing student cheating is an ongoing battle. Studies of a wide variety of institutions have found that as many as 82% of students surveyed self-reported that they have engaged in cheating or plagiarism (Bowers 1964; Greene and Saxe 1992; McCabe 2004b; Rettinger et al. 2004; Stern and Havlicek 1986). Between 1990 and 2004, Donald McCabe of Rutgers University—a leading researcher on cheating and plagiarism and the founder of the Center for Academic Integrity—surveyed over 75,000 students at approximately 125 post-secondary schools regarding their cheating behaviours. He found that in 1995, self-reported cheating ranged between 62% and 83% of students surveyed; however, data he collected after 2002 suggested that “more students are starting to cheat earlier in their college careers” (McCabe 2004b).

Most faculty are aware that such transgressions have genuine potential to create uncomfortable circumstances and spark student-faculty conflicts. It is little wonder, then, that both dealing with cheating and speaking face-to-face with a student about suspected academic integrity violations and the likely consequences have been characterized as stressful and emotionally draining and as one of the most negative aspects of teaching (Borg 2002; Keith-Spiegel et al. 1998).

As a result, it is not surprising that some instructors prefer to “look the other way” or pretend the incident did not happen. In fact, in a variety of studies, anywhere from 15% to 51% of instructors reported ignoring cheating (Barrett and Cox 2005; Dordoy 2002; McCabe 2004b; Tabachnick et al. 1991). In fact, from these studies and others, the consensus is that approximately 40% of faculty respondents have reported ignoring cheating on one or more occasions. Unfortunately, ignoring these behaviors has the potential to intensify the problem. As Volpe et al. (2008) indicated, “The discrepancy between faculty attitudes and their actual behaviors to control cheating in the classroom may be sending conflicting messages to students, which may ultimately influence the rates of student cheating.”

It is likely that many factors ultimately determine whether a faculty member takes action when presented with evidence of student cheating or plagiarism. This study examined the impact of previous negative experiences on the likelihood that an instructor would ignore or pursue an incident of student cheating. It also looked at general attitudes and beliefs of faculty who have reported ignoring one or more instances of cheating in the past.

Methodology

A survey instrument was developed to measure faculty attitudes regarding cheating and to determine what actions, if any, they have taken in the past when faced with an academic integrity violation. Participants were informed that the purpose of the study was to measure faculty responses to academic integrity violations, specifically, how an instructor deals with a student that he or she has reason to believe has cheated. On the survey instrument cheating was defined “as using unauthorized assistance or representing another person's work as one’s own. Operationally, it includes student behaviors such as copying another student’s test answers, use of a crib sheet, plagiarism, falsifying research, and other similar activities.” Many of the questions were designed to assess general attitudes, intent to take action, social norms, and past behavior, based on the theory that these are significant predictors of future behavior (Ajzen 1988; 1991). Those participants who indicated that they had previously spoken directly with a student suspected of cheating were asked to characterize the nature of the interaction for the most recent incident.

Questionnaires were distributed to 852 faculty from two major comprehensive universities: one located in the midwestern United States and the second located in western Canada. A potential list of participants was provided by the U.S. institution, and the list of faculty at the Canadian university was developed by using a publicly available web directory and departmental websites. Those in full-time administrative positions were excluded, resulting in the ultimate distribution of 379 questionnaires to faculty at the U.S. institution and 473 to those at the Canadian institution. Of these faculty members, 206 responded, yielding an overall response rate of 24.2%. This rate was within the range expected based upon the literature regarding surveys, which shows that long surveys elicit lower response rates than short surveys and that the use of multiple-item formats reduces response rates even further (Mangione 1995). It is also consistent with the fact that, if surveys ask questions that have ethical implications or career implications, expected response rates are typically in the 20 to 30% range (Aldridge and Levine 2001).

Past Experience

Participants were asked if they had ever spoken directly with a student they had reason to believe was cheating, and 83% responded that they had. These respondents were then asked to consider the last time they had spoken to a student suspected of cheating and to characterize the interaction using a scale based on six attitude items. A typical question was as follows:

The last time I spoke face-to-face with a student I had reason to believe had cheated, I would characterize the interaction between the student and me as: angry 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 calm

If the tone of the interaction were angry, stressful, or unpleasant and if the results of the interaction were found to be worthless, harmful, or generally unsatisfactory, the overall incident was defined as a “bad experience.”

To look at how such interactions affect behaviors and attitudes, a composite measure of experience was computed. After recoding to ensure all six items were in the same direction (i.e., larger scores reflecting more positive attitudes), the mean was computed (see Table 1) .

Respondents scoring less than the scale midpoint of 4 were grouped into the category “bad experience” (23.9%, n = 49). Those scoring above the midpoint (56.1%, n = 115) were grouped into a category titled “good experience.” The remaining respondents were at the scale midpoint of 4 (neutral) and were not included in the analysis. By definition, those in the bad experience group rated their last interaction less favorably, which is consistent for all scale items related to past experience.

Mann-Whitney U Tests were used to compare how the groups responded to various items. Non-parametric statistical tests were chosen for this set of questions because the distributions of responses on some items differed significantly from normality. The statistically significant items are indicated in Table 2, and specific items are highlighted in the discussion that follows.

It is clear that in comparison to their colleagues in the good experience group, individuals in the past bad experience group placed less importance on what other significant reference persons and groups think they should do. Those faculty members with prior bad experiences in dealing with cheating students assigned less importance to what the faculty in their department thought they should do (M = 4.22 versus M = 4.91, p < .01), what the chair thought they should do (M = 4.65 versus M = 5.39, p < .01), and what the dean thought they should do (M = 4.00 versus M = 4.95, p < .01). They seemed to generalize their own attitudes to others since they were also less likely to believe that other faculty in their department speak with cheating students (M = .056) than the good experience group was (M = 1.39, p < .001). Those in the bad experience group were less likely to think these individuals or groups expected them to speak face-to-face with students suspected of cheating.

Individuals in the bad experience group who had referred suspected cases of cheating to a dean, a chair, or another administrator or body also reported lower satisfaction with how the situation was handled (M = 3.47) than faculty in the good experience group (M = 4.00, p < .05). They were also less convinced (M = 4.60) that the university administration supported instructors who confront cheaters than the good experience group (M = 5.18, p < .05).

In terms of behavioral beliefs, those in the bad experience group felt less positively that speaking directly to students was the best way to handle such instances or that by doing so they were helping the students. On the other hand, those in the bad experience group were more likely to feel stressed (M = 5.71 vs. M = 4.64, p < .001), to believe that students could become emotional (M = 5.33 vs. M = 44.6, p < .01), and to believe that students may try to intimate them (M = 3.60 vs. M = 2.99, p < .01). Furthermore, they placed more importance on avoiding uncomfortable interactions with students (M = 0.27 vs. M = −0.49, p < .05). These data may explain why those in the bad experience group found dealing with student cheating to be one of the most negative aspects of the job (M = 5.85), more so than those in the good experience group (M = 4.67, p < .001). Most importantly, these data suggest why those who have had bad experiences in the past prefer to ignore cheating instances (M = 1.71) more than their colleagues (M = 1.42, p < .05) and why they have ignored more cheating instances in the past (M = .57 versus M = .38, p < .05).

In summary, it is evident that past experience is an important contributor to the likelihood that a faculty member would directly address an incident of suspected student cheating. Faculty members whose last experience was a bad one were more likely to characterize dealing with cheating as one of the most negative aspects of the job. These faculty members also indicated a lower regard for the expectations of important reference groups.

Faculty in the bad experience category were more stressed when dealing with students and expressed stronger beliefs that students may become emotional or try to intimidate them. In addition, those faculty members indicated that it is important for them to avoid feeling uncomfortable when interacting with students. Those in the bad experience category indicated a stronger preference than their colleagues for handling cheating by ignoring it, and they had also ignored cheating more times in the past. These findings suggest that a person with past bad experiences will be less likely to speak face-to-face with a student suspected of cheating, thus potentially adding to the body of faculty who are inclined to ignore such incidents.

Attitudes of Faculty Who Ignore Cheating

The previous section discussed the attitudes of faculty toward dealing with cheating incidents based on previous experience and disregarded whether or not they admitted to “turning a blind eye.” One might expect that temperament, social belief structure, or emotional response characteristics may influence which faculty members act upon incidents of student violations of academic integrity as opposed to those who ignore such events.

When asked if they had ever ignored a suspected incident of cheating, 40.3% (N = 83) of the 206 respondents answered “yes.” The question that naturally follows is this: how do these respondents differ from those who have never ignored a suspected incident of cheating (58.3%; N = 120)? The two groups were compared, and Mann-Whitney U Tests were conducted for significance. Table 3 indicates the items where statistically significant differences exist between faculty members who have never ignored an instance of cheating and those who indicated that they have ignored one or more instances in the past.

Those who had ignored cheating in the past indicated weaker attitudes toward speaking with a student about cheating compared to those who had never ignored a suspected incident of cheating. This was consistent for nearly all scale items related to direct measure of attitude.

It was a bit of a surprise to find that those that have ignored cheating were more likely to have spoken with suspected cheaters in the past (M = .90 versus M = .79, p < .05). It appears, however, that the quality of past experience was lower (M = 4.25) than that of other faculty who had never ignored suspected cheating (M = 4.63, p < .01); this finding is further supported by responses to items that asked about respondents’ last interaction with a student suspected of cheating.

Some of the behaviors seem to follow almost by definition: faculty who have ignored cheating were less likely to prefer dealing with a suspected cheater in a private face-to-face meeting (M = 5.65 versus M = 5.93, p < .05), and they were more likely to prefer to handle instances of cheating by ignoring them (M = 1.69 versus M = 1.39, p < .01). Faculty members who had ignored suspected cheating were in weaker agreement (M = 5.24) than their colleagues (M = 5.87, p < .01) that instructors should always deal with instances of cheating when suspected. Ignorers also agreed more strongly that dealing with cheating was one of the most negative aspects of the job (M = 5.31 versus M = 4.66, p < .05). Also noteworthy is that those who ignored cheating agreed more strongly (M = 1.73) with the statement “Cheating is acceptable under some circumstances” than their colleagues who had never ignored cheating (M = 1.44, p < .01).

A number of emotional and social differences also appeared for the group of ignorers. In general, faculty who reported that they had, at times, ignored cheating felt considerably more stressed than non-ignorers when speaking face-to-face with a suspected cheater (M = 5.32 as opposed to M = 4.57, p < .01). In support of this stance, they indicated that it was more important to avoid being involved in emotionally charged situations (M = .49) than did the non-ignorers (M = −.03, p < .05). In general, for them to speak face-to-face with a student they had reason to believe had cheated was (a) less necessary (M = 5.83 versus M = 6.13, p < 0.05), (b) less positive (M = 4.90 versus M = 5.24, p < 0.05), (c) less useful (M = 5.33 versus M = 5.82, p < 0.001), (d) more difficult (M = 2.68 versus M = 3.18, p < 0.05), and (e) more uncomfortable (M = 2.77 versus M = 3.32, p < 0.05) than for their colleagues. It naturally follows that faculty who had ignored cheating in the past were more likely to feel that speaking to the student placed them in a socially uncomfortable position (M = 5.08 for ignorers versus 4.35 for non-ignorers, p < .01). The importance of the emotional consequences for the ignorers was emphasized by their indication that if a student were likely to become emotional, they were less likely (M = −0.22) to speak with him or her than other faculty were (M = 0.07, p < .05).

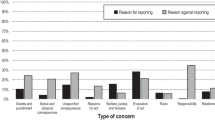

Faculty who indicated that they had ignored cheating were asked to identify what factors may have influenced their decisions to ignore the incidents. They were asked to indicate as many reasons as were applicable. A full breakdown of the reasons given for ignoring suspected cheating, organized by frequency of response, is presented in Table 4.

The reason given most was that insufficient evidence or proof existed (95.2%), distantly followed by “the cheating was trivial/not serious” (19.3%). Despite the fact that ignoring cheating may be related to several emotional and social factors outlined above, only 6% of the faculty indicated that they ignored cheating because it was too stressful or they did not want to deal with it.

It is apparent that several characteristics distinguish faculty members who indicated that they had ignored one or more cheating instances in the past from those who had never ignored an instance of cheating. The ignorers indicated weaker attitudes toward speaking face-to-face with students suspected of cheating, and they rated their past experiences with such interactions less positively.

Several emotional and social factors seemed to be at work for faculty who ignored cheating. They felt stressed when speaking to students about cheating, preferred to avoid emotionally charged situations, and indicated that if a student were likely to become emotional, they were less likely to speak to him or her. This may explain why they found dealing with cheating to be such a negative aspect of their job. Clearly, they did not feel as strongly that cheating must be addressed, and they were more likely to ignore academic integrity violations.

Insights into the Ignorers

In the absence of adequate interventions, student cheating will continue to thrive. Of the 206 faculty surveyed, 40.3% admitted to having ignored cheating. This finding is consistent with findings by previous researchers. Similarly, it was found that 47.8% of the faculty surveyed had never referred a suspected case of cheating to the chair, a dean, or another administrator or body. This result is comparable to findings by McCabe that indicate 44% have never referred a suspected case of cheating (McCabe 2004b).

We understand that faculty who have ignored cheating in the past are more likely to ignore it in the future. A look at some of the more intriguing results may illuminate the reasons why faculty consciously choose to not respond to violations of academic integrity by their students. Previous researchers have examined reasons given for ignoring cheating. McCabe (2004b) suggested that it is often because of a lack of evidence or sufficient proof . A less important but still significant factor McCabe cited was perceived lack of support from administration, cited by 6% of study participants. The most highly ranked reasons Keith-Spiegel and her fellow researchers (1998) found for ignoring cheating were as follows, starting with the most salient:

-

There was insufficient evidence that academic dishonesty actually occurred (e.g., peeking at a student’s paper, or dishonesty reported via a second-hand account);

-

The anxiety and stress involved in accusing and/or following through is too intense;

-

Going through a formal hearing is too onerous;

-

There was insufficient time to track down the source of suspected plagiarism;

-

The process of dealing with the incident was too time-consuming; and

-

Courage was lacking on the part of the professor.

In the present study, when asked directly which factors influenced their decision to ignore a cheating incident, the overwhelming majority of faculty (95.2%) indicated the reason for ignoring was insufficient evidence or proof. As one faculty member indicated on the survey, “Everyone would prefer evidence that is clear and overwhelming.” Another stated, “I have never spoken to a student about a suspicion of cheating unless I had evidence that made me feel confident.” On the other hand, since the majority of instructors indicated they have never ignored suspected cheating, one must assume that in some cases these faculty members are proceeding more on suspicion than on incontrovertible proof. Insufficient evidence or proof as a reason for ignoring cheating was distantly followed by “the cheating was trivial/not serious” (19.3%) and not enough time (12.1%). Only 6% of faculty indicated that they felt that it was too stressful or that they did not want to deal with it, while only 1.2% indicated that they “felt intimidated or fearful.”

It also appears that many members of the professoriate have developed their own internal strategies and policies determining when and if they choose to confront students engaged in unethical behaviors. For example, one U.S. instructor said she thought a student had plagiarized but could not be sure. She arranged to see the student who then denied plagiarizing and started crying. The instructor said, “It showed me they were scared.” In the end, she sent the student off with a stern warning and a lecture on potential future consequences. Another faculty member stated that he does not hesitate to discuss suspected cheating with a student, but in regards to referring the matter to the dean or judicial system, “I have brought charges against several students over my career. I only do this when I have evidence I think will stand up.” One faculty member said that she goes straight to a student with her suspicions:

I believe that the student must understand that their actions have been discovered as early as possible…Once caught they will likely tell their friends that their cheating method did not work, and that may scare them off of trying the same thing themselves.

One instructor felt that iron-clad evidence was unnecessary and that if there was reason enough to suspect a student, there was reason enough “to throw a scare” into them.

Two out of five faculty members admitted to ignoring instances of cheating, and while the issue of insufficient evidence is perhaps legitimate for some, especially in ambiguous situations, it may also simply be a rationalization for others to justify ignoring the situation. The data make it very clear that the ignorers feel that by confronting the student or taking other action, they are being placed in a socially uncomfortable situation and, thus, perceive dealing with cheating as one of the most negative parts of the job. Value expectancy theory suggests that people will go to great lengths to avoid such situations. Since denial and avoidance are two ways that people typically cope with stress, perhaps anticipated stress and negative emotional outcomes are more likely explanations for ignoring cheating. Insufficient evidence may be the leading cause mentioned in various studies simply because it is a convenient rationalization and it is psychologically more comforting for a faculty member to suggest that there is an objective reason to justify avoiding a face-to-face confrontation with a student, rather than an emotional reason having to do with his or her own personality.

Researcher Christopher Anderson (2003) offered some interesting insights as to what might be at work here. In his work on decision avoidance, which he says “manifests itself as a tendency to avoid making a choice by postponing it or by seeking an easy way out that involves no action or no change” (Anderson 2003), he suggested “that in all such cases there is a mixture of a few good, rational reasons for avoidance and a more complex and rationally questionable role played by emotions such as regret and fear.” Among the “rational” reasons are that avoidance gives the best payoff, buys time, or maintains the status quo. The emotional reasons center around the fact that avoidance reduces real or anticipated regret and regulates negative emotions such as fear, anxiety, and tension.

It has already been recognized that faculty members find dealing with suspected cheating to be stressful, emotionally charged, and socially uncomfortable. In effect, these are emotional reasons to avoid dealing with incidents of suspected cheating. The rational reasons are typically expressed as “lack of administrative support,” “lack of time,” or “insufficient evidence or proof.” The data, however, show that a factor with more importance may be the fact that ignorers have typically had lower quality experiences in the past. This factor may cause them to sincerely believe that dealing with cheating students does not turn out well either for the faculty member or the student. Quite possibly, they may have had decisions reversed, which they feel may have affected their credibility or standing in their department or, at the very least, may have affected their sense of control of this aspect of their job. There is little surprise then, as Anderson (2003) stated, that “other things being equal, selection of status quo, omission, or deferral options should act to reduce regret when bad outcomes are experienced.” This “rational-emotional” model for decision avoidance does seem like is a useful paradigm to explain why some faculty members tend to ignore cheating and to avoid direct action.

As previously mentioned, the issue of insufficient time to deal with cheating arises frequently in the literature (Dordoy 2002; Keith-Spiegel et al. 1998; Mainka and Raeburn 2006). One respondent noted the following:

Pursuing cheating cases takes many hours and lots of emotional energy, usually at the busiest time of the semester. Whether I pursue something is in part due to time. No one reduces my other work if I spend 20 hours in a week on a plagiarism case for a course paper.

Another faculty member discussed a case he handled and said, “Although it was resolved successfully in the end it took a HUGE amount of my time. Faculty need more support for the time we are expected to put into this.”

The issue of “lack of time” is worth clarifying in future studies since the magnitude of this time expenditure has ramifications for the type of support and policies that institutions should put in place. Keith-Spiegel and her fellow researchers (1998) focused on the drain on faculty working time when suspected plagiarism in student papers must be addressed. Here, the time factor refers to efforts to track down the source from which the student copied. Since that study, many new tools have become available to assist instructors in tracking down plagiarists; one of the most popular is Turnitin.com. In McCabe’s (2004a) survey and in the present study, the critical item simply read “not enough time,” which could be ambiguously interpreted as referring to time needed to set up a meeting and then speak face-to-face with the student or to the entire process of detective work, meetings with others associated with the matter, preparation of correspondence, and any time needed to prepare for and navigate through administrative processes and hearings. It may also be possible that some instructors are running afoul of deadlines set out in institutional policies, such as dates when grades must be submitted or grade changes entered. One instructor commented on the fact that “there may a delay in setting a time to meet with the student. The result is that the time permitted to remedy the situation could be compromised.”

Time is clearly an issue for some faculty, and the requirements to assemble and advance a case may become quite cumbersome, especially once senior administrators or lawyers become involved. Author and historian A. J. Sherman (2005) commented,

At least some of the strain academics chronically complain of arises from the pressure requiring them often to adjudicate or at least investigate suspected malfeasance and other questionable actions or utterances. The sheer amount of time and effort devoted to these quasi-judicial proceedings sometimes gives the university a peculiar atmosphere more appropriate to a courthouse or attorney general’s office than a place of learning.

On the other hand, “lack of time” may be just another excuse for inaction. Anderson also pointed to the role that time pressures play in decision avoidance: “An individual does not yield to time pressure and choose because the aversive contingencies of the choice powerfully motivate organisms to escape these situations; so long as avoidant options are available, they are preferred regardless of time limitations.”

Most likely, other personality-related issues explain why some faculty take no action against suspected cheaters. The data suggest that the faculty who ignore are more inclined to believe that cheating is acceptable under some circumstances and are less supportive of the statement that instructors should always deal with instances of cheating when suspected. Tabachnick et al. (1991) asked a sample of 482 teaching psychologists if “ignoring strong evidence of cheating” was an ethical behaviour. The majority (69.3%) rejected such conduct by answering “unquestionably not,” and the remaining participants gave answers ranging from “under rare circumstances” to “unquestionably yes.” That item inspired a similar one in this study with the following phrasing: “Cheating is acceptable under some circumstances.” Similar to the aforementioned study, 68.4% of participants indicated strong disagreement. In addition, the precise pattern of answers resembled those in the Tabachnick et al. study: the dissenting faculty either indicated less than strong disagreement, and unexpectedly, a group of 4.9% explicitly approved (or at least did not disapprove) of cheating. Where do such attitudes come from? Since the study clearly defined cheating at the outset, it can be assumed there was not confusion over the terminology. Is it possible that these instructors have a different “ethical package” than other members of the Academy?

The existing data and the literature offer some insight. Keith-Spiegel et al.’s (1998) study with a group of 129 teaching psychologists included an item concerning “feelings such as guilt left over from the professor’s own cheating incidents when he or she was a student.” In the present study, the ignorers indicated one of their reasons for ignoring cheating was “I felt I was partially responsible for the action” (8.4%). The same percentage (8.4%) indicated “lack of support from administration.” Equally intriguing are beliefs among the majority of respondents that students who cheat in school are likely to engage in other dishonest behaviours and that researchers who cheated as students are more likely to engage in scientific misconduct.

Is too much fuss being made over “a few bad apples” and a comparatively small number of faculty members who are simply choosing “to look the other way”? Faculty are on the frontlines for maintaining academic integrity, and the controversy that sparked at Ohio University in 2006 provides a practical demonstration of what can happen due to neglect or inaction. The institution was dealing with allegations of widespread plagiarism of theses in the mechanical engineering department that apparently occurred over a 20-year period. According to the dean of the college of engineering, “There was a subculture associated with a small number of faculty members that, while it might not have actively encouraged plagiarism, did not rigorously attempt to prevent it.” (Wasley 2006). The committee also recommended removal of the plagiarized theses from the library, and 39 had been removed for further review. The report of the independent review committee was somewhat less kind, saying,

The vast majority of the cases revolve around three faculty members who either failed to monitor the writing in their advisees theses or simply ignored academic honesty, integrity and basically supported academic fraudulence…We are appalled that three members of the faculty in mechanical engineering have so blatantly chosen to ignore their responsibilities by contributing to an atmosphere of negligence toward issues of academic misconduct in their own department. (Meyer and Bloemer 2006)

Among the committee recommendations were (a) a review of 106 theses and seven dissertations, (b) suspension of three current doctoral students, (c) dismissal of the department chair, and (d) discipline or reprimand of faculty. (Meyer and Bloemer 2006)

According to Wasley reporting in The Chronicle of Higher Education (2006), “Dozens of former students are now caught up in the investigation, several professors have been reprimanded, and the university is wrestling with how one department fostered a culture of academic cheating.” Clearly, the institution entered full investigative and damage-control mode since there was widespread media reporting and a subsequent tarnishing of its institutional reputation. The chairman of the Graduate Student Senate indicated that instead referring to Ohio as a “party school,” they say, “Oh, you go to the plagiarism school.” But perhaps the most disturbing comment in the article was the closing quote attributed to the dismissed chair of the mechanical engineering department: “At any university, at any department, I think you would find the same”

It appears that factors related to the actions or backgrounds of some faculty allow them to consider ignoring strong evidence of cheating as unimportant and not requiring action on their part. This study has highlighted several of the differences in attitudes and beliefs that distinguish faculty who ignore cheating from those who do not. Perhaps more disconcerting is the fact that some faculty members are able to view cheating as acceptable under some circumstances. This is clearly an area that needs additional investigation since it reflects on the integrity of the Academy, the validity of its assessments of competence, and the degrees that it awards. In such matters, we cannot repeat the words of Lord Nelson who maintained he had “a right to be blind sometimes.”

References

Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Chicago: Dorsey.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Aldridge, A., & Levine, K. (2001). Surveying the social world: Principles and practice in survey research. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Anderson, C. J. (2003). The psychology of doing nothing: forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 139.

Barrett, R., & Cox, A. L. (2005). At least they’re learning something: the hazy line between collaboration and collusion. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(2), 107–122.

Borg, E. (2002, July). Northumbria University lecturers’ experiences of plagiarism and collusion. Paper presented at the First Northumbria Conference—Educating for the Future, Newcastle on Tyne, UK.

Bowers, W. J. (1964). Student dishonesty and its control in college. New York: Bureau of Applied Social Research, Columbia University.

Dordoy, A. (2002, July). Cheating and plagiarism: Student and staff perceptions at Northumbria. Paper presented at the First Northumbria Conference—Educating for the Future, Newcastle on Tyne, UK.

Greene, A. S., & Saxe, L. (1992). Everyone (else) does it: Academic cheating. Paper presented at the meeting of the Eastern Psychological Association Convention, Boston, MA. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED347931)

Hibbert, C. (1998). Nelson: A personal history. Toronto: HarperCollins Canada.

Keith-Spiegel, P., Tabachnick, B. G., Whitley, B. E., Jr., & Washburn, J. (1998). Why professors ignore cheating: opinions of a national sample of psychology instructors. Ethics and Behavior, 8(3), 215–227.

Mainka, C., & Raeburn, S. (2006). Investigating staff perceptions of academic misconduct: First results in one school. Paper presented at the Second International Plagiarism Conference, The Sage Gateshead, UK.

Mangione, T. W. (1995). Mail surveys: Improving the quality. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

McCabe, D. L. (2004a). Academic integrity: Rutgers University faculty survey. Retrieved from http://integrity.rutgersedu/rutgersfac.asp

McCabe, D. L. (2004b, October 9–11) Student cheating: Crisis or opportunity? Paper presented at the Center for Academic Integrity Conference, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS.

Meyer, G. D., & Bloemer, H. (2006). Plagiarism in the department of mechanical engineering in the Russ College of Engineering at Ohio University. Retrieved from http://www.ohio.edu/outlook/media/BMIR.cfm

Rettinger, D. A., Jordan, A. E., & Peschiera, F. (2004). Evaluating the motivation of other students to cheat: a vignette experiment. Research in Higher Education, 45(8), 873–890.

Sherman, A. J. (2005). Schools for scandal. New England Review, 26(3), 82–91.

Southey, R. (1908). The life of Horatio Lord Nelson. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/947.

Stern, E. B., & Havlicek, L. (1986). Academic misconduct: results of faculty and undergraduate student surveys. Journal of Allied Health, 5(2), 129–142.

Tabachnick, B. G., Keith-Spiegel, P., & Pope, K. S. (1991). Ethics of teaching: beliefs and behaviours of psychologists as educators. American Psychologist, 46(5), 506–515.

Volpe, R., Davidson, L., & Bell, M. C. (2008). Faculty attitudes and behaviors concerning student cheating. College Student Journal, 42(1), 164–175.

Wasley, P. (2006, August 11). The plagiarism hunter. Chronicle of Higher Education, p. A8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coren, A. Turning a Blind Eye: Faculty Who Ignore Student Cheating. J Acad Ethics 9, 291–305 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-011-9147-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-011-9147-y