Abstract

Self-compassion refers to a kind and nurturing attitude toward oneself during situations that threaten one’s adequacy, while recognizing that being imperfect is part of being human. Although growing evidence indicates that self-compassion is related to a wide range of desirable psychological outcomes, little research has explored self-compassion in older adults. The present study investigated the relationships between self-compassion and theoretically based indicators of psychological adjustment, as well as the moderating effect of self-compassion on self-rated health. A sample of 121 older adults recruited from a community library and a senior day center completed self-report measures of self-compassion, self-esteem, psychological well-being, anxiety, and depression. Results indicated that self-compassion is positively correlated with age, self-compassion is positively and uniquely related to psychological well-being, and self-compassion moderates the association between self-rated health and depression. These results suggest that interventions designed to increase self-compassion in older adults may be a fruitful direction for future applied research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As life expectancies have climbed in the last century, the proportion of people reaching late adulthood has increased dramatically. Thus, an important direction for research on aging is to explore factors that are associated with thriving in late life. It is likely that self-compassion is such a factor. This construct has recently emerged as a correlate of a wide range of desirable psychological outcomes, and experimental work has shown that it is possible to increase self-compassion. However, research on self-compassion in older adults is limited. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to explore associations between self-compassion and well-being in late life.

There are two distinct approaches to conceptualizing well-being (Ryan and Deci 2001). Subjective well-being (also referred to as hedonic well-being) refers to an emotionally pleasant and satisfying life. It is usually operationalized as high satisfaction with life, frequent positive emotions, and infrequent negative emotions (Diener 1984). In general, older adults tend to score as high as younger people on measures of subjective well-being, a phenomenon called the paradox of well-being. Ample evidence supports this finding; for example, a major review of data from 60,000 individuals aged 20–99 spanning dozens of countries concluded that life satisfaction is relatively stable across the life span in most societies (Diener and Suh 1998). Partially due to the consistency of this finding, some have argued that subjective well-being perhaps represents “successful living” at any age more than “successful aging” (Ryff 1989b).

In contrast to subjective well-being, psychological well-being (also referred to as eudemonic well-being) focuses on fulfillment of human potential (Keyes et al. 2002). The most comprehensive extant model of psychological well-being was developed by Ryff (1989a) based on descriptions of optimal functioning within humanistic, developmental, and personality traditions. This model operationalizes psychological well-being in terms of six unique dimensions, each of which articulates different challenges that people encounter as they strive to live a rich and fulfilling life. The dimensions include positive evaluations of oneself and one’s life (self-acceptance), a sense of continued growth and development as a person (personal growth), the belief that one’s life has meaning and purpose (purpose in life), the experience of quality relationships with others (positive relationships with others), the capacity to effectively manage one’s life (environmental mastery), and a sense of self-determination (autonomy). Eudemonic well-being typically shows only moderate correlations with measures of subjective well-being, supporting the idea that it is a distinct aspect of psychological functioning (Keyes et al. 2002; Ryff 1989a). Furthermore, as noted by Ryff and Keyes (1995), an individual who is striving to actualize his/her potential may not feel pleasant emotions in the short term, but presumably will achieve a deeper level of fulfillment and satisfaction in the long run.

Ryff’s model of psychological well-being was developed with an intentional focus on life span development. It encompasses the ideas of developmental theorists such as Erikson (1959), Neugarten (1973), and Buhler (1935), all of whom described development as a process of continual growth across the life span. As such, the model is particularly relevant for assessing well-being in late life. It is to be expected that there would be age-related changes along the six dimensions described by Ryff, because psychosocial tasks and environmental challenges change as a function of age, and evidence supports this idea. A cross-sectional study of young, middle-aged, and older adults showed that personal growth and purpose in life declined in later life, environmental mastery and autonomy increased, and self-acceptance and positive relationships with others remained stable across adulthood (Ryff 1989a).

Because eudemonic well-being focuses on the fulfillment of human potential, it is important to identify and explore factors that can facilitate its development. One possible factor is self-compassion. Self-compassion refers to a kindhearted way of relating to one’s failures, weaknesses, and disappointments. It is composed of three interrelated components: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness (Neff 2003a). Self-kindness refers to treating oneself with forgiveness, warmth, sensitivity, and acceptance, particularly in the face of failures or personal weakness. Common humanity involves the recognition that struggles, sorrows, and imperfections are part of the human experience and that we are not alone in our struggles. Mindfulness involves noticing and acknowledging painful thoughts and feelings, but without becoming consumed by those thoughts.

Self-compassion is distinct from self-esteem, which is often defined as favorable global evaluations of the self (Baumeister et al. 1996). Although the two constructs tend to be related, their correlates are different, and self-compassion shows associations with a variety of psychological outcomes even when controlling for self-esteem (Leary et al. 2007; Neff and Vonk 2009). Conceptually, self-compassion differs from self-esteem because it does not involve evaluations of self or feeling superior to others. Instead, it is based on unconditional feelings of kindness and acceptance toward the self while simultaneously holding to a realistic understanding of one’s inadequacies. Self-esteem has been linked with greater denial and defensiveness (Crocker and Park 2004; Leary et al. 2007) while self-compassion is associated with honestly confronting one’s role in failures, more balanced emotional reactions, and a willingness to learn from mistakes (Breines and Chen 2012; Leary et al. 2007).

Substantial evidence indicates that self-compassion is related to many desirable psychological outcomes. Self-compassionate people tend to report more happiness, greater life satisfaction, lower negative affect, and fewer symptoms of psychological distress (such as anxiety and depression) than less self-compassionate individuals (Leary et al. 2007; Macbeth and Gumley 2012; Neff et al. 2007a, b; Neff and Vonk 2009). Self-compassion is also related to many other positive psychological constructs, including optimism, wisdom, curiosity, and personal initiative (Neff et al. 2007b). In addition to correlational studies, experimental manipulations of self-compassion have been shown to increase positive affect and decrease negative feelings about the self when compared to control groups without self-compassion inductions (Leary et al. 2007). Therapeutic interventions designed to elevate self-compassion have been shown to produce concomitant decreases in self-criticism, depression, rumination, and anxiety (Neff et al. 2007a).

Self-compassion may play a particularly important role in later life. It has been proposed that older adults’ subjective well-being depends more on their interpretation of their circumstances than on the circumstances themselves (Siedlecki et al. 2008), and a self-compassionate mindset could provide a gentle, accepting perspective on many effects of aging. Although research on self-compassion in older samples is limited, existing evidence supports this idea. For example, self-compassion moderated the relationship between physical health and subjective well-being in older adults, such that participants who reported poorer physical health also reported high subjective well-being only when they had high self-compassion (Allen et al. 2012). In addition, self-compassionate individuals reported being less troubled by the use of assistance such as using a walker or another person for stability, asking others to repeat themselves, or using memory strategies than did people with lower self-compassion (Allen et al. 2012). An experimental study assigned older participants to reflect upon either a positive, negative, or neutral age-related event. Results showed that self-compassion was related to more positive responses to increasing years, including the belief that one’s attitude can help cope with aging (Allen and Leary 2013). Finally, self-compassion showed positive associations with subjective well-being, ego integrity, and meaning in life in older adults (Phillips and Ferguson 2012), as well as positive associations with attitudes toward aging in midlife women (Brown et al. 2015).

Although self-compassion shows robust associations with subjective well-being in young, old, and multigenerational samples, researchers have not yet explored the connection between self-compassion and eudemonic well-being in older adults. As individuals negotiate the multiple challenges of later life, it is likely that a self-compassionate attitude would facilitate optimal resolution. For example, recognition of increased limitations could challenge positive feelings toward the self (self-acceptance) and one’s sense of self-determination (autonomy). However, self-compassion responds to perceived shortcomings with understanding and comfort, which could help the individual to accept physical or social changes without denigrating the self or giving up. Self-compassionate people recognize that aging and its accompanying changes are part of the shared human condition, and this recognition would help individuals to feel connected to others (positive relationships with others) and to endeavor to find meaning in age-related changes (purpose in life). Pursuing challenging, growth-related activities (personal growth) in later life involves risk of failure, but a self-compassionate attitude makes room for the possibility of failing, without shame or self-judgment.

It is likely that self-compassion increases with age, although this relationship has not yet been clearly established. Across the life span, negative affect tends to decrease and positive affect tends to increase. One explanation for this trend is that through years of life experience, people’s perspectives change and they learn how to regulate their emotions in a way that will avoid negative experiences (Charles et al. 2009). For example, when younger and older adults were asked to verbalize their responses to negative comments directed toward them, younger adults were more likely to make disparaging remarks toward the speakers, while older adults made fewer comments about what they had heard and focused less on the criticism (Charles and Carstensen 2008). Although the study did not explicitly test the role of self-compassion, it is likely that through the struggles and disappointments that accompany decades of life, older people shift toward a gentler, more forgiving perspective toward themselves and others.

Finally, it is likely that self-compassion can serve as a buffer against the psychological impact of health problems. Although most older adults are healthy and live independently, health problems become more likely with increasing age, and there is a strong relationship between subjective rating of overall health and symptoms of depression and anxiety (El-Gabalawy et al. 2011; Han 2002; Mokrue and Acri 2015). Previous research showed that poorer physical health was associated with lower subjective well-being in older adults, but this relationship was moderated by self-compassion (Allen et al. 2012). The present study sought to extend these findings by exploring the relationship between subjective health and depression and anxiety.

Thus, the purpose of the present study was to explore the relationships between self-compassion and psychological functioning in older adults. First, it was hypothesized that self-compassion would increase over the decades of adulthood. Second, it was hypothesized that self-compassion would uniquely predict the six facets of psychological well-being as delineated by Ryff (1989a). The third hypothesis was that self-compassion would moderate the association between general physical health and anxiety and depression. Specifically, it was expected that poorer physical health would show an association with increased anxiety and depression, but this relationship would be weaker for those with high self-compassion.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and all participants were treated in accord with guidelines established by the American Psychological Association.

Older Adults Sample

The first sample consisted of older adults. Participants were recruited from two locations: a local public library and a community senior center. At both locations, an advertisement for the study was posted. Participants were told that a five-dollar donation would be made to the host site in exchange for completing a survey that would take 15–20 min. If interested, participants were given a large envelope containing the study. They were free to complete it on-site or take it home and bring it back when completed. Only participants age 60 and up were eligible for the study.

The final sample of older adults consisted of 126 participants (37 men and 89 women) ranging in age from 59 to 95 with a mean age of 70.59 (SD = 7.84). All participants were White. Overall, they were well-educated (72.6 % had at least some college). Self-rated annual household income was as follows: 29.6 % earned <$30,000, 38.9 % earned from $30,000 to $60,000, and 31.5 % earned more than $60,000. About half the participants were married (54.7 %), 25.6 % were widowed, and the remaining 19.7 % were divorced, never married, or in another partnership.

Multigenerational Sample

This sample consisted of the 126 individuals in the older adults’ sample (described above), as well as 170 additional people. The additional 170 participants were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. MTurk is a website that provides online “workers” with opportunities to complete online tasks for monetary compensation. It is recognized as a source of quality data for social science research and tends to provide greater diversity than college samples (Buhrmester et al. 2011). A brief description of the study, including estimated duration and compensation, was posted on the MTurk website and interested participants were directed to a survey link. They completed a variety of measures intended for a different study (Homan 2014); the only measures that were used for the present study were self-compassion and the demographic question about age. The MTurk sample consisted of 170 participants (124 male and 46 female) who ranged in age from 18 to 63 years (M = 28.49 years, SD = 9.20). They were mostly White (78.2 %) and well-educated (85.2 % had at least some college).

Measures

Self-Compassion

The 12-item Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (Raes et al. 2011) was used to measure the extent to which participants are compassionate toward themselves. Its items (e.g., “I try to be understanding and patient toward those aspects of my personality I don’t like”) are rated on a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The short form correlated almost perfectly with the original, longer version of the scale (Neff 2003b) and showed good internal consistency among Dutch and American undergraduate students and middle-aged adults (Raes et al. 2011). It also demonstrated criterion-related validity via its ability to predict changes in depression over a 5-month period (Raes 2011). Item responses were reversed where necessary and averaged to create a single self-compassion score, with higher scores indicating greater self-compassion.

Self-Esteem

The Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale (SISE; Robins et al. 2001) was used to assess self-esteem. The SISE consists of the item, “I have high self-esteem” and participants indicate agreement with this item using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not very true of me) to 5 (very true of me). The SISE was strongly correlated with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg 1965) and this correlation was consistent across gender, ethnic groups, college students and community members, different occupational statuses, and over four years of college. The SISE and the RSE also showed a nearly identical pattern of correlates with a wide variety of outcome variables (Robins et al. 2001).

Psychological Well-Being

Psychological well-being was measured with a modified version of the Scales of Psychological Well-Being (PWB; Ryff and Keyes 1995). The scale consists of six subscales including self-acceptance (e.g., “I like most aspects of my personality”), positive relationships with others (e.g., “I feel like I get a lot out of my friendships”), personal growth (e.g., “I have the sense that I have developed a lot as a person over time”), purpose in life (e.g., “I have a sense of direction and purpose in life”), environmental mastery (e.g., “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live”), and autonomy (e.g., “I have confidence in my opinions, even if they are contrary to the general consensus”). Respondents indicate agreement with each item using a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). The original version of the SPWB consisted of 14 items per subscale, with a total of 84 items. In order to reduce participant burden, the present study used the modification developed by van Dierendonck (2005). The purpose of the modification was to develop relatively short scales that would demonstrate internal consistency and factorial validity. The resultant subscales were made up of 6–8 items, and all subscales showed correlations greater than r = .90 with Ryff’s original measure and satisfactory internal consistencies. Items were reversed when necessary, and items comprising each subscale were averaged.

Psychological Distress

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-Short Form (DASS; Lovibund and Lovibund 1995) was used to assess symptoms of depression and anxiety. The seven-item Depression subscale is based on primary symptoms of depression (e.g., “I felt that I had nothing to look forward to,” “I felt downhearted and blue”). The seven-item Anxiety subscale is based on primary symptoms of anxiety (e.g., “I was aware of dryness of my mouth,” “I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself”). Participants rate each symptom on the basis of its severity during the previous week using a 4-point response scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). Items were averaged for each subscale with higher scores indicating greater depression or anxiety. The DASS-SF Depression scale showed a strong, positive correlation with the Beck Depression Inventory (r = .79) and the Anxiety subscale also showed a strong, positive correlation with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (r = .85; Antony et al. 1998).

Demographics

Participants also answered questions about basic demographic information including age, sex, years of education, income, ethnicity, relationship status, and general overall health (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent).

Results

To determine the correlation between age and self-compassion, it was important to include a full range of ages. For this reason, the multigenerational sample was used. Based on these 296 cases that ranged in age from 18 to 95, there was a significant correlation between age and self-compassion (r = .32, p < .001), indicating that self-compassion tended to increase with years lived. Only the older adult sample was included in subsequent analyses.

Descriptive statistics, including internal consistency coefficients, and intercorrelations for the major study variables are presented in Table 1. Data were examined for normality, and skew and kurtosis values were within recommended limits for multiple regression analyses (Kline 2010).

In order to test the unique contribution of self-compassion to psychological well-being, six hierarchical regression analyses were performed. In each analysis, one of the six psychological well-being dimensions was regressed on a set of control variables. Self-esteem was controlled in order to tease out the unique contribution of self-compassion (as opposed to a general sense of feeling positively about oneself). Because age, gender, and education have been shown to correlate with some aspects of psychological well-being, these variables were also controlled (Keyes et al. 2002; Ryff 1991). Finally, because most definitions of successful aging include the absence of physical disability (Depp and Jeste 2006), we also controlled for self-rated health. In Step 2, self-compassion was entered. Results are presented in Table 2. For every PWB variable, self-compassion explained unique variance, above and beyond the set of control variables, indicating that as self-compassion increases, these markers of optimal psychological development also increase. Effect sizes were large, ranging from R 2 = .21 for the total model involving autonomy as the criterion variable to R 2 = .61 for the total model for self-acceptance.

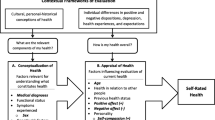

In order to test the moderating effect of self-compassion on physical and mental health, a second set of hierarchical regression analyses was performed. Self-rated health and self-compassion were mean centered. At Step 1, one of the mental health variables (anxiety or depression) was regressed on self-rated health and self-compassion. At Step 2, an interaction term, formed by multiplying these two predictor variables, was entered. For the first analysis, self-rated health significantly predicted anxiety (β = −.186, t = −1.97, p = .050) but self-compassion did not (β = −.164, t = −1.734, p = .086) and the interaction term also was not significant (β = −.063, t = −.690, p = .491, ∆R 2 = .004). When depression was the criterion variable, both self-rated health and self-compassion were significant predictors (self-rated health β = −.164, t = −2.193, p = .030; self-compassion β = −.586, t = −7.830, p < .001). The interaction term was significant (β = .310, t = 4.663, p < .001, ∆R 2 = .094), indicating that the relationship between self-rated physical health and depression was conditional upon self-compassion. In order to probe this interaction, a plot of the regression line for self-rated health predicting depression at two levels of self-compassion (plus and minus one standard deviation from the mean) was created and is presented in Fig. 1. At low levels of self-compassion, poorer self-rated health was strongly related to increased depression, β = −.237, t = −4.820, p < .001. However, at high levels of self-compassion, self-rated health did not show a statistically significant relationship with depression, β = .095, t = 1.793, p = .085.

Discussion

The present study found that (a) self-compassion increased with age, (b) self-compassion uniquely predicted six dimensions of psychological well-being in older adults, and (c) self-compassion moderated the relationship between subjective ratings of overall health and depression. In general, these results are consistent with previous work showing that self-compassion is related to a wide range of desirable outcomes. Yet, these findings extend previous work by showing that self-compassion is related to developmentally relevant indices of optimal functioning in late adulthood.

Previous studies have produced inconsistent conclusions regarding age-related changes in self-compassion. In light of the present results, this inconsistency is best explained by restricted age ranges. Studies that have included only part of the adult life span have not found a significant correlation between age and self-compassion, while this study and another that included the full range of adulthood did find a significant relationship (Neff and Vonk 2009). Neff and Vonk suggested that self-compassion may not increase until people have reached Erikson’s stage of integrity, which involves an introspective review of one’s life, including both successes and failures, and coming to terms with that life. It is also possible that self-compassion increases as part of a broader shift in perspective and growing desire to avoid negative experiences (Charles and Piazza 2009). Perhaps the accumulation of life experience gradually leads people toward a more self-compassionate approach to life in later years.

Self-compassion showed robust associations with six dimensions of eudemonic well-being in older adults, suggesting that self-compassion can serve as an asset in resolving the developmental tasks of late life. Eventually, aging involves loss of loved ones and declines in health and function. Rather than responding to these undesired life changes with anger, self-criticism, and bemoaning, a self-compassionate attitude enables people to cope with the challenges of aging by treating themselves with kindness and care, regarding their circumstances as part of the shared human experience, and maintaining an objective perspective on negative emotions (Neff 2003a).

One of the core elements of self-compassion is treating the self with kindness and caring. By definition, this element involves recognizing and accepting one’s weaknesses as well as strengths. Thus, it is not surprising that there was a robust association between self-compassion and self-acceptance, even after controlling for self-esteem. It is also logical that treating oneself with a forgiving, accepting attitude would show an association with more satisfying personal relationships. Developmental theorist Erik Erikson postulated that a stable sense of identity is a prerequisite for close, intimate relationships; thus, the realistic self-appraisal that is inherent in a self-compassionate mindset likely promotes self-acceptance, which in turn facilitates the quality of interpersonal relationships.

The links between self-compassion and personal growth and environmental mastery are perhaps best explained from a motivational perspective. Self-compassion is associated with realistic self-appraisal, which in turn is associated with growth-related outcomes (Kim et al. 2010). Thus, it is logical to think that self-compassion itself would increase self-improvement motivation, and this hypothesis was tested experimentally in a series of studies that included a self-compassion induction (Breines and Chen 2012). Specifically, people who were induced to take a self-compassionate approach to a personal weakness reported greater self-improvement motivation (such as the desire to learn and improve oneself, or the intention to seek out challenges that would enhance growth as a person) than others who were assigned to either a self-esteem induction or a positive distraction control condition. Participants in the self-compassion condition also indicated a stronger sense that they were capable of making positive changes and had the confidence to do so. This experimental study provides compelling evidence that self-compassion increases people’s desire to continue to seek out growth and development as a person (personal growth) and their capacity to effectively manage their lives (environmental mastery).

This study found that self-compassion buffered older adults from the negative impact that health problems can have on depression. In general, as self-rated health declined, symptoms of depression increased. However, for people with high self-compassion, this association was weaker (failing to reach statistical significance), suggesting that self-compassion is particularly beneficial for people with poorer health. This finding has potentially important implications in light of evidence that depression is a unique contributor to heart disease and mortality in older adults (Schulz et al. 2000a). A study of more than 5000 older persons showed that those with elevated depressive symptoms were more likely to die within the 6-year follow-up period than those who had low levels of depressive symptoms, even after controlling for socioeconomic, disease, and lifestyle risk factors (Schulz et al. 2000a). Among individuals with heart disease, those who show depressive symptoms are more likely to die than people with equivalent heart disease but are not depressed (Glassman and Shapiro 1998). Other research has also shown that self-compassion is related to lower rates of depression (MacBeth and Gumley 2012; Homan 2014); thus, the present findings suggest that interventions that focus on promoting self-compassion among older adults could yield positive health effects.

Self-compassion was broadly associated with positive outcomes and although the correlational design of the present study does not demonstrate causality, it is conceivable that self-compassion promotes these benefits. A growing body of experimental work has shown that self-compassion can be modified and that increasing self-compassion can lead to more positive emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses. For example, after receiving an 8-week mindfulness self-compassion workshop, community adults experienced gains in self-compassion and well-being, which were maintained at a year follow-up (Neff and Germer 2013). Participants in an experimentally induced self-compassion condition evidenced greater motivation to improve themselves than others who had been assigned to a self-esteem or control condition (Breines and Chen 2012). Neff et al. (2007a) measured self-compassion and various indices of well-being one week before and three weeks after participants completed a clinical technique that encouraged challenging self-critical, judgmental beliefs, and growing in empathy. Results showed that increases in self-compassion were correlated with improvements in well-being, including increased social connectedness and decreased self-criticism, depression, rumination, thought suppression, and anxiety. These studies and others (e.g., Albertson et al. 2014; Baker and McNulty 2011; Leary et al. 2007) support the idea that self-compassion is malleable and that increasing self-compassion can produce better psychological functioning. An important direction for future research is to explore whether self-compassion interventions can increase psychological flourishing in late life.

This study had some limitations. First, as mentioned previously, the cross-sectional, correlational design does not allow conclusions about causality. Although it is plausible that self-compassion promotes psychological well-being in late life, it is also possible that enhanced well-being leads to higher self-compassion, or that a third variable underlies these relationships. Another limitation was that the study relied on self-report measures, which are always a cause for concern. Finally, the sample was generally healthy, well-educated, and young-old. Additional research is needed to explore the role of self-compassion among older adults who are experiencing greater challenges to their health and adjustment.

Despite these limitations, this study makes an incremental contribution to the self-compassion literature by demonstrating that self-compassion is linked with greater fulfillment of potential in late life. These findings imply that self-compassion training programs tailored to older adults and their unique challenges could yield valuable benefits. Most generally, this study adds to the growing evidence that self-compassion is an asset for psychological flourishing at any age.

References

Albertson, E. R., Neff, K. D., & Dill-Shackleford, K. E. (2014). Self-compassion and body dissatisfaction in women: A randomized controlled trial of a brief meditation intervention. Mindfulness,. doi:10.1017/s12671-014-0277-3.

Allen, A. B., Goldwasser, E. R., & Leary, M. R. (2012). Self-compassion and well-being among older adults. Self and Identity, 11, 428–453. doi:10.1080/15298868.2011.595082.

Allen, A. B., & Leary, M. R. (2013). Self-compassionate responses to aging. The Gerontologist, 54, 190–200. doi:10.1093/geront/gns204.

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Swimson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10, 176–181. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176.

Baker, L. R., & McNulty, J. K. (2011). Self-compassion and relationship maintenance: The moderating roles of conscientiousness and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 853–873. doi:10.1037/a0021884.

Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological Review, 103, 5–33. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.103.1.5.

Breines, J. G., & Chen, S. (2012). Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 1133–1143. doi:10.1177/0146167212445599.

Brown, L., Bryant, C., Brown, V., Bei, B., & Judd, F. (2015). Self-compassion, attitudes to ageing and indicators of health and well-being among midlife women. Aging and Mental Health. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1060946.

Buhler, C. (1935). The curve of life as studied in biographies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 19, 405–409.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980.

Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2008). Unpleasant situations elicit different emotional responses in younger and older adults. Psychology of Aging, 23, 495–504. doi:10.1037/a0013284.

Charles, S. T., & Piazza, J. R. (2009). Age differences in affective well-being: Context matters. Social and Personality Compass, 3, 711–724. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00202.x.

Charles, S. T., Piazza, J. R., Luong, G., & Almeida, D. M. (2009). Now you see it, now you don’t: Age differences in affective reactivity to social tensions. Psychology and Aging, 24, 645–653. doi:10.1037/a0016673.

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 392–414. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.392.

Depp, C. A., & Jeste, D. V. (2006). Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 6–20. doi:10.1176/foc.7.1.foc137.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542.

Diener, E., & Suh, M. E. (1998). Subjective well-being and age: An international analysis. In K. W. Schaie & M. P. Lawton (Eds.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics. Focus on emotion and adult development (Vol. 17, pp. 304–324). New York: Springer.

El-Gabalawy, R., Mackenzie, C. S., Shooshtari, S., & Sareen, J. (2011). Comorbid physical health conditions and anxiety disorders: A population-based exploration of prevalence and health outcomes among older adults. General Hospital Psychiatry, 33, 556–564. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.07.005.

Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. Psychological Issues, 1, 18–164.

Glassman, A. H., & Shapiro, P. A. (1998). Depression and the course of coronary artery disease. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 4–11. doi:10.1176/ajp.155.1.4.

Han, B. (2002). Depressive symptoms and self-rated health in community-dwelling older adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50, 1549–1556. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50411.x.

Homan, K. J. (2014). A mediation model linking attachment to God, self-compassion, and mental health. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17, 977–989. doi:10.1080/13674676.2014.984163.

Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 1007–1022. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007.

Kim, Y.-H., Chiu, C., & Zou, Z. (2010). Know thyself: Misperceptions of actual performance undermine achievement motivation, future performance, and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 395–409. doi:10.1037/a0020555.

Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Allen, A. B., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 887–904. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887.

Lovibund, S. H., & Lovibund, P. F. (1995). Depression anxiety stress scales-short form. Retrieved from www.psy.unsw.edu.au/dass/.

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 545–552. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003.

Mokrue, K., & Acri, M. C. (2015). Subjective health and health behaviors as predictors of symptoms of depression and anxiety among ethnic minority college students. Social Work in Mental Health, 13, 186–200. doi:10.1080/15332985.2014.911238.

Neff, K. D. (2003a). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–101. doi:10.1080/15298860309032.

Neff, K. D. (2003b). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250. doi:10.1080/15298860309027.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 28–44. doi:10.1002/jclp.21923.

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007a). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 139–154. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004.

Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. L. (2007b). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 908–916. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.08.002.

Neff, K., & Vonk, R. (2009). Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of Personality, 77, 23–50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00537.x.

Neugarten, B. L. (1973). Personality change in late life: A developmental perspective. In C. Eisdorfer & M. P. Lawton (Eds.), The psychology of adult development and aging (pp. 311–335). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Phillips, W. J., & Ferguson, S. J. (2012). Self-compassion: A resource for positive aging. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68, 529–539. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs091.

Raes, F. (2011). The effect of self-compassion on the development of depression symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Mindfulness, 2, 33–36. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0040-y.

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18, 250–255. doi:10.1002/cpp.702.

Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewsi, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 151–161. doi:10.1177/0146167201272002.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141.

Ryff, C. D. (1989a). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

Ryff, C. D. (1989b). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest for successful aging. International Journal of Human Development, 12, 35–55. doi:10.1177/016502548901200102.

Ryff, C. D. (1991). Possible selves in adulthood and old age: A tale of shifting horizons. Psychology and Aging, 6, 286–295. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.6.2.286.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being, revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719.

Schulz, R., Beach, S. R., Ives, D. G., Martire, L. M., Ariyo, A. A., & Kop, W. J. (2000a). Association between depression and mortality in older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160, 1761–1768. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.12.1761.

Schulz, R., Martire, L. M., Beach, S. R., & Scheier, M. F. (2000b). Depression and mortality in the elderly. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 204–208. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00095.

Siedlecki, K. L., Tucker-Drob, E. M., Oishi, S., & Salthouse, T. A. (2008). Life satisfaction across adulthood: Different determinants at different ages? Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 153–164. doi:10.1080/17439760701834602.

van Dierendonck, D. (2005). The construct validity of Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-Being and its extension to spiritual well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 629–643. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(03)00122-3.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant awarded by the JMM Fund at Grove City College. The author would like to thank Alice Thompson and Samara Wild for their help with data management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Homan, K.J. Self-Compassion and Psychological Well-Being in Older Adults. J Adult Dev 23, 111–119 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-016-9227-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-016-9227-8