Abstract

The empty nest, which refers to the phase of the family life cycle following the departure of children, has been associated with both positive and negative consequences for parents. This article aims to achieve a better understanding of the complex effects of this transition. It discusses available data and theoretical perspectives on the empty nest, from pioneering works until the most recent studies on the subject. It includes a discussion of conceptualization and methodological issues, as well as a review of determinants of nest leaving. The influence of the departure of children on their parents’ marital quality and psychological well-being, including the potential development of empty-nest syndrome, are then summarized. Studies examining other parental outcome, such as marital instability or relationships with adult children, are also reviewed. It ends with a discussion on boomerang kids and directions for future research. In particular, the need to study the empty-nest period with parents living in a variety of marital situations is acknowledged.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During its life cycle, the family alternatively grows and contracts in size (Sussman 1955). This contraction of the immediate family is associated, in particular, with the empty nest, a period faced by most parents during their midlife. The empty nest, also called the postparental period, is the phase of the family life cycle during which all the children are grown up and are no longer living at home (Dennerstein et al. 2002; Deutscher 1964; Raup and Myers 1989). This period is regarded as a normative event, in the sense that parents are aware that their children will become adults and eventually leave home (Crowley et al. 2003; Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009). Although normative, this transition nevertheless has a deep impact on parents. It has long been recognized that, as its size decreases, interaction and activity patterns have to be modified if the family is to persist as a unit (Sussman 1955).

Strikingly less attention has been devoted to this period compared with other stages of the family life cycle, such as the transition to parenthood (Hagen and DeVries 2004; Lachman 2004). This situation is of great concern to researchers for at least two reasons. First, the postparental period has lengthened in recent decades (Borland 1982; Cassidy 1985; Hershberger 1982) and nearly half of a marriage is typically spent after the children have left home (Duvall and Miller 1985). Second, the empty nest engenders complex emotions, both positive and negative, for parents (Beaupré et al. 2006; Dare 2011; Hiedemann et al. 1998; Sheriff and Weatherall 2009). The current article aims to offer readers a comprehensive outlook at available data and theoretical perspectives on the postparental period by reviewing research published on this subject in the last few decades. Understanding the conditions under which couples can experience a more positive transition constitutes one of the first steps in promoting well-being among these couples.

To complete this examination, published studies were extracted from academic databases, with empty nest, postparental, postmaternity, postpaternity, postparenthood, launching of children, launching phase, life course, life cycle, normative leaving-home trajectory, and nonnormative leaving-home trajectory as the search criteria (with a variety of spellings). The term empty nest was, by far, the most frequently used by researchers. The goal of this search was to make an inventory of what has been published annually, from pioneering works until the most recent studies on the subject. The article begins with a brief historical overview and the presentation of a series of terms related to the transition, followed by a discussion of determinants of nest leaving. I continue by analyzing the complex effects of nest leaving on parents and conclude with a discussion on previously independent adults who return home. Finally, future directions in research are proposed.

Historical Perspective and Conceptual Developments

Studies on the empty-nest period started in the 1950’s (Sussman 1955) or 1960’s (Axelson 1960; Deutscher 1964), but became more numerous in the 1970’s (Crawford and Hooper 1973; Glenn 1975; Harkins 1978; Resnick 1979). The emergence of the empty-nest phase is largely a consequence of increasing longevity (Deutscher 1964; Raup and Myers 1989). If median ages of death in men are taken as criteria, the postparental period did not begin to appear until about 1900 (Deutscher 1964; Hershberger 1982; Schram 1979). Increased longevity results in a longer period of time for the average couple to reside by themselves after their children have gone. Changes in birth control technologies and in fertility values, which have led to smaller families and a compression of the childbearing years, also explain the lengthening of the postparental period over the years (Cassidy 1985; Rodgers and Witney 1981; Schram 1979).

The remaining of this section presents terms central to this review. Like many other areas of study related to family life, children’s departure from the parental home has given rise to budding conceptual developments. On the one hand, a number of researchers have underlined their preference for the term postparental over the colloquial term empty nest. They argued that the use of the term empty nest has contributed to the pessimistic view of this developmental phase (Raup and Myers 1989; Sheriff and Weatherall 2009) and to ageist attitudes in adult development research (Lippert 1997). I would add that the expression empty nest is not completely accurate either: if parents are still living in their home, the nest is not empty.

On the other hand, a few scholars have underlined that, because a parent remains a parent even after children leave home (Cooper and Gutmann 1987), the very term postparental is also inexact (Gutmann 1985). Gutmann (1985) proposed an alternative term by suggesting that older individuals become emeritus parents rather than ex-parents. Although the term emeritus parent does not suffer from the same problems as the two other terms, it sank into oblivion since Gutmann’s proposition. In the current review, whenever possible, I use the term emeritus parents, but I also use the terms postparental and empty nest for easing correspondence with previous research. The last two terms have the merit of being largely accepted by the scientific community, whereas the first one describes, with a fair degree of accuracy, the reality under study.

Many researchers distinguish the launching phase from the empty-nest phase. The launching phase refers to the stage when a family is in the process of having children depart from the parental home (Feeney et al. 1994; Hagen and DeVries 2004). In the launching phase, the oldest children may have left home, but younger children may still be living with their parents. The launching phase ends when the last child leaves home (Ellicott 1985; White 1994). The recognition of the existence of a launching phase takes into consideration that, particularly in families with more than one child, an empty nest does not occur overnight; there is usually a transitional nest-emptying period (Cooper and Gutmann 1987).

The departure of children has also been linked to the concept of empty-nest syndrome. This term describes the depression, loneliness, identity crisis, or emotional distress experienced by parents during the postparental phase (Borland 1982; Cassidy 1985; Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009). The concepts of empty nest and empty-nest syndrome have sometimes been used interchangeably (Dare 2011), which has accentuated the potential for postparenthood to be interpreted as problematic. To eliminate any confusion, it is important to acknowledge that the term empty nest describes the stage of family life, whereas the term empty-nest syndrome refers to possible negative reactions to the transition. Finally, the relatively new issue of adult offspring who leave the home and return again has given rise to expressions such as boomerang kids (Beaupré et al. 2006; Sheriff and Weatherall 2009), incompletely launched adults (Schnaiberg and Goldenberg 1989) or return of the fledgling adults (Clemens and Axelson 1985).

Determinants of Nest Leaving

Before examining the effects of nest leaving on emeritus parents, predictors of the departure of children are reviewed. Today, most young adults move out voluntarily from the parental home to pursue educational or employment opportunities or simply to live independently (Beaupré et al. 2006). The bulk of home leavers relocate close to their parental home (Leopold et al. 2012). Unsurprisingly, age is an important determinant of nest leaving. A majority of adults perceive that both men and women should leave home between the ages of 18 and 25 (Settersten 1998). The reasons cited for these age deadlines are related to the development of self and personality, including the expression of independence (Settersten 1998; White 1994). Indeed, results showed that coresidence probabilities decreased steeply with children’s age (Aquilino 1991). This movement is, however, hindered by another trend showing that, since the 1980’s, the average age for leaving home has increased in many western countries (Cherlin et al. 1997), largely as a result of young adults’ financial problems (Beaupré et al. 2006; Clemens and Axelson 1985). Whether young adults can sustain themselves economically is, like age, a strong determinant of their level of independence from their parents (Cherlin et al. 1997).

Offspring’s gender is also a significant predictor of nest leaving. Results have consistently showed that women leave the parental home earlier than men, largely because they tend to marry at younger ages than do men (Beaupré et al. 2006; Cherlin et al. 1997; Settersten 1998; White 1994). Nevertheless, men with higher education leave sooner than their less educated counterparts (Beaupré et al. 2006).

A number of characteristics of the family of origin also influence the departure of children. Growing up in a large family promotes being independent sooner rather than later (Beaupré et al. 2006). Young adults living in step-families also leave earlier (Beaupré et al. 2006). Although most children in step-families reveal that the level of family conflicts was the reason for their departure (White 1994), the link between family conflicts and home leaving is still a matter of debate. Seiffge-Krenke (2006) confirmed that the rates of parent–adolescent conflict were higher in families of in-time leavers (M = 21 years for women and M = 23 years for men) than in families with adult children residing with their parents at ages 21–25 years. Families of in-time leavers would exhibit an optimal balance between encouragement of their children’s differentiation, through conflict, and support of their autonomy. Ward and Spitze (2007), for their part, found only very limited evidence that nest leaving was related to the quality of parent–child relations. These authors proposed that future research assessing the process through which children from step-families leave home earlier should investigate economic and structural factors. Finally, when all other factors were maintained constant, Beaupré et al. (2006) revealed that having a mother who was not in the paid labor force during offspring’s adolescence reduced the probability that young adults move out of the parental home. In contrast, the effect of having an unemployed father was not significant.

Effects of Nest Leaving on Emeritus Parents

Prominent Theories

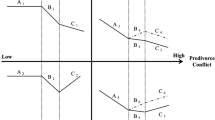

Two main theoretical perspectives offer hypotheses regarding the effects of the departure of children on parents: the role loss perspective and the role strain (relief) perspective. Both perspectives are supported by empirical data and are reviewed here. The role loss hypothesis predicts that when the role from which parents, particularly mothers, have derived their sense of accomplishment is over, a decrease in their well-being should be observed (Rogers and Markides 1989; Sheriff and Weatherall 2009; White and Edwards 1990). Most studies have conceptualized parental well-being in terms of parents’ marital quality or psychological well-being. The empty-nest syndrome is postulated to be closely linked to the absence of alternative roles in which parents could continue building an identity after the departure of their children (Borland 1982; Bumagin and Hirn 1982).

In sharp contrast to the hypothesis of a loss, the role strain relief perspective suggests that the empty-nest stage should lead to improvement in parental well-being, because the presence of children at home increases exposure to stressors, such as daily demands, time constraints, and work–family conflicts (Erickson et al. 2010; Umberson et al. 2005; Umberson et al. 2010; White and Edwards 1990). Partners who no longer have children at home may engage in fewer roles, thus reducing their role strain and stress (Gorchoff et al. 2008). The role strain relief hypothesis was supported by a fairly consistent finding throughout the literature that children have an unfavorable influence on marital quality (Ahlborg et al. 2009; Bradbury et al. 2000; Umberson et al. 2005).

Methodological Issues

The examination of studies published in the last few decades reveals variations in methodological designs and in samples employed to document the postparental period. Before reviewing results of research examining the effects of the departure of children on parental well-being, these methodological issues are discussed here.

Many studies, particularly the earlier ones in the domain, were based on cross-sectional data. A number of researchers explored how adults differed in their levels of well-being according to different stages of the family life cycle (Condie and Doan 1978; Erickson et al. 2010; Radloff 1980; Rollins and Cannon 1974; Rollins and Feldman 1970). Most of the time, the eight-stage model of Duvall and Miller (1985; I-married couples without children, II-childbearing families, III-families with preschool children, IV-families with schoolchildren, V-families with teenagers, VI-launching stage, VII-empty-nest stage, and VIII-aging family members), or a slightly modified version of this model, was used to categorize individuals. Other authors have focused their investigation specifically on the departure of children by comparing parents in the launching phase with their counterparts in the empty-nest phase (Axelson 1960; Harkins 1978; Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009; Rogers and Markides 1989). Unfortunately, cross-sectional studies, particularly those comparing couples who were in a variety of stages of the family life, do not allow for distinguishing the stage effects from the cohort membership effects. Researchers examining the impact of the postparental transition have also used retrospective ratings of well-being in lasting marriages (Finkel and Hansen 1992; Mackey and O’Brien 1999). Retrospective studies are not flawless either. As they are based on respondents’ recollections, they are likely to contain inaccuracies.

Given the limitations associated with cross-sectional and retrospective data, a number of scholars chose longitudinal methodologies to examine the effects of family transitions, including the postparental transition. A number of them collected short-term longitudinal data over periods no longer than 5 years (Menaghan 1983; Tucker and Aron 1993; Ward and Spitze 2007). The longest longitudinal studies, which covered either all stages of the family life or only the period surrounding the empty-nest stage, took place over periods of approximately 10 years (Dennerstein et al. 2002; Hagen and DeVries 2004; White and Edwards 1990), 18 years (Gorchoff et al. 2008), and 40 years (Vaillant and Vaillant 1993).

Instead of using the stages of the family life cycle as benchmarks, others have contrasted the effects of postparenthood with diverse transitions or stressors, such as involuntary job loss (Crowley et al. 2003; Hobdy et al. 2007), grand-parenthood (Crawford and Hooper 1973), menopause, divorce, aging, or death of parents (Dare 2011). Comparisons have also been made between emeritus parents and childless adults (Dykstra and Keizer 2009; Hansen et al. 2009).

The vast majority of reviewed studies were based on quantitative analyses, but some authors have differentiated themselves by using qualitative data (Dare 2011; Deutscher 1964) or a methodology mixing quantitative and qualitative analyses (Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009). In the same vein, most researchers employed convenience samples, but a number of studies have the merit of being based on national surveys (Glenn 1975; Kapitus and Johnson 2003; VanLaningham et al. 2001; Ward and Spitze 2007) or representative samples (Hansen et al. 2009). Finally, given that both mothers and fathers face the postparental transition, most scholars studied the impact of launching of children into adulthood on both parents. Nevertheless, many articles only concern mothers (Bumagin and Hirn 1982; Crawford and Hooper 1973; Gorchoff et al. 2008; Harkins 1978; Harris et al. 1986; McQuaide 1998). This choice was explained by the fact that the departure of children entails a change in a role that has traditionally been a focus of many women’s lives and identities (Hobdy et al. 2007).

Average Effects

Many researchers examined the effects of the departure of children on emeritus parents’ marital quality and psychological well-being, including the potential development of empty-nest syndrome. Other parental outcomes, such as marital instability, relationships with adult children, marital equity, or physical well-being, have also been examined but less intensively. The results are presented here. A summary of the main ideas of this section appears in Table 1.

Marital Quality, Equity and Instability

Cross-sectional studies have consistently revealed a curvilinear U-shaped pattern of marital quality over the family life course, with lowest ratings in the mid marriage child rearing stages and highest ratings in the earliest and latest stages, including the empty nest (Adelmann et al. 1996; Anderson et al. 1983; Kapitus and Johnson 2003; Rollins and Cannon 1974). Retrospective ratings of marital quality also followed the same curvilinear pattern described in cross-sectional studies (Finkel and Hansen 1992; Mackey and O’Brien 1999). Consistent with the role strain relief perspective, results based on cross-sectional and retrospective studies indicated that after the child rearing and launching phases, both fathers and mothers showed a substantial increase in their marital quality and satisfaction (Glenn 1975; Harris et al. 1986; Rollins and Feldman 1970; Umberson et al. 2005). The increase was, however, more marked for emeritus mothers than emeritus fathers (Rollins and Feldman 1970). This gender difference was explained by the traditional gender ideology, which generally prescribes higher levels of engagement with their children to mothers (Gutmann 1985).

Results of longitudinal studies were slightly less consistent. A study by Vaillant and Vaillant (1993) showed that, when studied prospectively, the U-curve disappears and marital satisfaction remains relatively stable, particularly in the middle and later years. Nevertheless, most longitudinal studies confirmed that parents in the empty-nest phase reported higher levels of marital satisfaction than when they were in the launching phase (Gorchoff et al. 2008; Hagen and DeVries 2004; White and Edwards 1990). The transition to an empty nest was associated with increased marital satisfaction that endured long after the last child left home (Gorchoff et al. 2008).

Many factors explain the rise in marital satisfaction at the empty-nest phase. Results showed that the transition to an empty nest increased marital quality via an increase in enjoyment of time with partners (Cassidy 1985; Gorchoff et al. 2008; see also Condie and Doan 1978, for a similar hypothesis). Partners expressed pleasure at their newfound freedom to do what they desired (Bozett 1985; Deutscher 1964; McQuaide 1998; Sussman 1955). Furthermore, compared with adults with dependent children, those who no longer have dependent children at home reported less work–family conflicts (Erickson et al. 2010), which allowed them to focus on their marital relationship.

The departure of the last child also has a positive impact on the level of equity between partners (i.e., the balance between what each partner feels he/she gives to the relationship and what is obtained; Menaghan 1983). According to a number of studies (Feeney et al. 1994; see also Holahan 1984), more wives than husbands experience equity during this period. This means that emeritus parents, particularly mothers, see their spouse as more accommodating, less insistent on their own way, and less focused on their own needs (Menaghan 1983). For these older spouses, adherence to strict equity assumes prime importance as a predictor of marital satisfaction (Feeney et al. 1994).

In contrast to results for marital quality and equity, Hiedemann et al. (1998) found evidence that the transition to an empty nest can increase the risk of marital dissolution, especially for couples who reach this phase relatively early in their marriage. Women appeared to be more likely than men to initiate separation at this stage of life (Pryor 1999). For their children’s benefit, it seems that a number of couples may have remained in unsatisfactory relationships until they reached the postparental phase (Hiedemann et al. 1998). Young adults whose parents separated were evenly divided on whether or not they thought it would have been better for them if their parents had separated when they were children (Pryor 1999; see also Cole and Cole 1999).

Relationships with Adult Children and Physical Well-Being

Ward and Spitze (2007) found little effect of nest leaving on the quality of parent–child relations. Nevertheless, the need to negotiate new sets of relationship rules with young adult children, particularly daughters, was a theme that emerged in the qualitative interviews of many emeritus mothers (Dare 2011). As the empty nest nears, role shifts also occur in father-child relationships. According to Bozett (1985), the father becomes less authoritarian and directive and the child becomes more receptive to the father’s suggestions and influence.

Earlier work showed that parents who lived near their children’s household, and maintained harmonious relations with them, experienced no basic change in their activity pattern across the postparenthood stage (Sussman 1955). Their relationships with their children and grandchildren kept them busy. Finally, the few studies examining the effect of the transition on parents’ physical health found no significant effect (Harkins 1978; Rogers and Markides 1989).

Psychological Well-Being

Research has been slightly incoherent regarding the impact of the departure of the last child from the home on parents’ psychological well-being. A small number of studies revealed that the empty nest was associated with difficulties for parents, especially for mothers. Nevertheless, the majority of studies published in recent decades painted a more optimistic picture of the situation. As will be shown, the nature of the variables under study and the presence of moderators could explain these inconsistencies.

With regards to documented difficulties, a number of mothers reported a significant increase in loneliness between the launching phase and the empty-nest phase, which was accounted, in part, by a decrease in their levels of community activities (Axelson 1960). These results are consistent with recent data showing that one of the rewards of becoming a parent is greater social integration (Nomaguchi and Milkie 2003). Postparenthood is often perceived by women as being stressful, that is more stressful than grand-motherhood or involuntary job loss (Crawford and Hooper 1973; Hobdy et al. 2007). In the same vein, in accordance with the role loss perspective, Lippert (1997) revealed that a sense of loss was a common feeling for emeritus mothers. Alcohol abuse may even accompany this feeling (D’Amore 2009).

If we turn our attention to factors behind these results, we find that the absence of alternative roles in which to continue building an identity after children leave home explains the negative effects of children departure on women’s psychological well-being (Borland 1982; Raup and Myers 1989; Resnick 1979). The accumulation of stressful events for some women could also be at stake. Raup and Myers (1989) observed that emeritus mothers who had major issues with which they were confronted at the time of the postparental transition, such as the death of parents, were more likely to suffer from the empty-nest syndrome than other mothers.

Nevertheless, many researchers failed to find differences in psychological well-being or life satisfaction between parents with residential children, including those in the launching phase, and parents in the empty-nest stage (Axelson 1960; Dykstra and Keizer 2009; Gorchoff et al. 2008; Hansen et al. 2009). Moreover, there is evidence that relatively few mothers and fathers experience the plethora of negative emotions and adjustment difficulties that are diagnosed as the empty-nest syndrome (Lewis and Duncan 1991; Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009; Raup and Myers 1989; Rogers and Markides 1989; Schmidt et al. 2004). A number of authors brought to light that children’s departure from home often generates, instead of strictly negative or positive emotions, ambivalence and mixed feelings (e.g., a mixture of sadness and relief; Dare 2011; Sheriff and Weatherall 2009). These mixed feelings are triggered in response to different aspects of active parenting (Sheriff and Weatherall 2009).

With regards to results providing a more optimistic overview of the transition, they showed that parents whose children have left home reported greater well-being as well as lower levels of depression than other respondents of comparable age with children at home (Dennerstein et al. 2002; Ellicott 1985; Glenn 1975; Harkins 1978; Radloff 1980; White and Edwards 1990). However, this improvement in mood was confined to parents who had frequent contact with nonresident children (White and Edwards 1990) or who were not worried about children leaving home (Dennerstein et al. 2002; Raup and Myers 1989). The positive effects of the empty nest on parental well-being appear to be the strongest immediately after children left (White and Edwards 1990) and they could have largely disappeared 2 years following the event (Harkins 1978). The fact remains that emeritus mothers reported higher levels of life satisfaction compared with childless women (Hansen et al. 2009). Additionally, Dare (2011) revealed that most mothers better managed the empty nest than the aging and death of parents, which presented them with more long-term challenges.

Contextual Variables

The departure of children from home does not occur in a vacuum and specific contextual variables have a particular influence on the way parents deal with the transition. In accordance with life cycle theories, which state that the degree of impact of an event has much to do with its timing (Elder 1998; Neugarten 1976), it has been shown that parental expectations regarding the appropriate timing of their children’s departure greatly influence experiences of the transition (Harkins 1978; Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009). If the empty-nest period occurred too soon or too late based on their social lens, parents had a more difficult time coping with the event. Correspondingly, when children met normative expectations about leaving, parents were less likely to report problems (Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009).

Parents’ demographic characteristics—including their occupational status, the number of children they had, and their age at the time of the postparental transition—also have an impact on the way they deal with the departure of their children. In line with the role loss perspective, a recent study showed that parents who worked part time or stayed at home were slightly more likely to suffer from the empty-nest syndrome than those employed in full-time jobs (Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009). In contrast, data from earlier decades converged to indicate that employment status, including being retired or not, did not influence how the transition was experienced (Cassidy 1985; Deutscher 1964; Radloff 1980). The unprecedented changes observed in recent years in the labor force, especially among women (Major and Germano 2006), render these results difficult to compare and could explain, to some extent, these inconsistencies. Concerning the impact of the other demographic variables, Ellicott (1985) revealed that women who had many children over a shorter period of time underwent more positive changes after their children left home compared with those with fewer children, which is in keeping with the role strain relief hypothesis. Finally, younger parents reported greater challenges associated with the transition to an empty nest compared with their older counterparts (Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009). The smoother adjustment of older parents was explained by the fact that they had a longer period of mental preparation to ease into the transition (Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009).

It is worth noting that the trajectory of couples undergoing the postparental transition is mostly independent of parental assessments of how children turned out (Gorchoff et al. 2008; Hagen and DeVries 2004; but see also Umberson et al. 2010). Although women who had experienced the transition to an empty nest viewed their children as more successful and independent than did women who still had children at home (Dare 2011), perceived child success was not linked to a more positive transition (Gorchoff et al. 2008; Hagen and DeVries 2004).

Gender and Cultural Differences

In the popular press, the term empty-nest syndrome was raised typically in relation to women (Cassidy 1985; Sheriff and Weatherall 2009). When men were construed as more likely to suffer emotionally from the departure of their children, it was because of their regret for being absent fathers as well as their inability to share their emotions with others (Sheriff and Weatherall 2009). A number of researchers found differences between reactions of emeritus mothers and fathers (but see Hagen and DeVries 2004, for similar patterns of results between genders). In contrast to accounts of the popular press, gender differences were, however, mostly favorable to women, in line with the role strain relief perspective (Erickson et al. 2010; Umberson et al. 2005; Umberson et al. 2010; White and Edwards 1990). Indeed, in the same way that the birth of a first child was associated with larger declines in marital satisfaction for women than for men, the empty nest was also associated with more positive results for women (Feeney et al. 1994; Glenn 1975; Rollins and Feldman 1970). The fact that mothers have typically the greatest responsibility for children explains these gender differences (Twenge et al. 2003). Nevertheless, when emeritus parents were asked if they had experienced the empty-nest syndrome, mothers were more likely than fathers to state that they had (Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009). In this last case, it is possible that some women tried, by their affirmative responses, to comply with images of mothers portrayed in the popular press (see McFarland et al. 1989, for similar results concerning the relation between women’s theories of menstrual distress and their recollections of physical and affective symptoms).

Before ending this section, I will address cultural differences. The postparental period has been documented mainly with American parents. As the number of empty-nesters has increased in China, especially in rural areas (Liu and Guo 2008; Xie et al. 2010), more and more research has involved Chinese parents. According to Su et al. (2012), emeritus parents is today’s group of social concern in China (see also Kumagai 2010 for a discussion of aging families in Japan where coresidence with adult children is the most prevalent situation). Data converged to indicate that Chinese empty-nesters were more inclined to have poorer relationships with their children, poorer family functioning, and to be unsatisfied with their life compared with their counterparts with children at home (Liu and Guo 2007, 2008; Wang and Zhao 2012). Furthermore, more than 80 % of Chinese emeritus parents reported moderate to high levels of loneliness (Wu et al. 2010). The prevalence of depressive symptoms among this population also approximated 80 % (Xie et al. 2010). The rapid erosion of family support (due in part to the mobility of children from rural areas to large cities for occupational reasons; Chen et al. 2012) is one of the factors that could contribute to parental difficulties (Liu and Guo 2007; Wang and Zhao 2011). Family support for older people is a long and cherished Chinese tradition (Wong and Leung 2012). Its importance is evidenced by data showing that empty-nesters living in urban areas not only receive more social support but also report less depression than those living in rural areas (Su et al. 2012). Finally, Chinese emeritus parents had frequently low incomes, which could also reduce their quality of life (Liu and Guo 2008; Xie et al. 2010). In terms of an overall portrait, Chinese data differ from American data in their greater degree of pessimism. However, the Chinese data confirm the American data on the mechanisms. Thus, the cultural differences could be due to the presence of a higher proportion of parents who suffer from living far from their adult children.

Data from another Asian country, Thailand, are more optimistic concerning the impact of children’s mobility. In this country, emeritus parents show lower levels of depression when their adult children move outside their district of residence than when they stay closer (Abas et al. 2013). Social status and pride associated with successful migration of children are key explanations of these findings. These data reinforce the fact that families are cultural products of their society (Kumagai 2010).

Boomerang Kids

It is apparent that the phenomenon of boomerang kids has grown in recent years. Roughly half of young adults have returned home for at least a brief period of time—usually assumed to be a minimum of 4 months (Beaupré et al. 2006)—after their initial leaving (Cherlin et al. 1997; White 1994). This situation was accentuated by young adults’ problems of unemployment, financial distress, and marital instability, but factors such as dependence or protection needs could also be involved (Aquilino 1991; Clemens and Axelson 1985). Contemporary parents seem accommodating with regards to the return of previously independent adults. According to Settersten (1998), most adults believe that returning home should not be limited by age and that coresidence with parents should be tailored along the dimensions of need and circumstances.

Some authors argued that prolonged coresidence was more likely in families where intergenerational ties were positive (Cherlin et al. 1997). Nevertheless, results indicated that returning children and their parents are able to share housing despite problematic histories (Ward and Spitze 2007). Although coresidence increases opportunities for disagreements (Ward and Spitze 2007), relationships between boomerang kids and their parents are generally positive (Cherlin et al. 1997). The areas of greatest potential conflicts are similar to the ones experienced with adolescents and include the lifestyle of the retuning adult, the sharing of household tasks, and the use of the family car (Clemens and Axelson 1985).

Concerning parents’ quality of life, results showed a trend toward reduced frequency of sexual activities in the first year after children return home (Dennerstein et al. 2002). Living with adult children also seems to interfere with positive interactions between parents (Umberson et al. 2005). In short, in the same way that the departure of the children has a positive impact on parent’s marital satisfaction, the return of these same children negatively affects their marital relationship. The return of adult children was, however, not associated with mood changes among women (Dennerstein et al. 2002), but do seem disturbing for many fathers (Lewis and Duncan 1991).

Future Directions in Research

In summary, the overall portrait of the consequences of children’s departure on their parents is relatively positive or at least not highly negative. This review made it clear that there is nevertheless strong variability in the way the transition to an empty nest is experienced (see Lachman 2004, for a similar argument). Researchers need to continue identifying what factors influence how emeritus parents experience the transition to an empty nest, instead of pursuing the search to describe the way things are. Work is still needed to fully comprehend factors that mediate and moderate outcomes for emeritus parents.

A key way to accomplish this is through the examination of the effects of the postparental transition in conjunction with other aging-related changes, such as grand-parenthood, chronic health conditions, menopause, retirement, widowhood, caring for elderly parents, or death of parents (see Mitchell and Lovegreen 2009, for a similar suggestion). So far, researchers focused on a preliminary step by comparing the effects of the departure of children with the effects of other events occurring at midlife, but an examination of the combined effects of stressors has been neglected. The few data available on the subject look promising in explaining individual differences. According to Raup and Myers (1989), there is evidence that facing other stressful events at the time of the postparental transition may increase the chances of developing the empty-nest syndrome.

Moreover, it is important to underscore that studies on the postparental period were based mostly on married couples. In this respect, emeritus parents coming from nontraditional families have been largely ignored in research. There is an urgent need to study the empty-nest period with samples of parents living in a variety of marital situations, such as remarriage, step-parenthood, divorce, cohabitation, or single parenthood (see Ward and Spitze 2007, for a similar argument). It can be hypothesized that the reality of emeritus parents coming from nonintact families would differ from the one of their intact counterparts (Raup and Myers 1989; Xie et al. 2010). For instance, if the emeritus mother or father is left living alone following the children’s departure, the effects of the transition may well be distinctively negative in most cases (Glenn 1975).

Additional research is also needed that further explores gender and cultural differences in psychological reactions to children leaving home. Mitchell and Lovegreen (2009) showed, on that subject, that some ethnocultural subgroups of fathers were more likely to report the empty-nest syndrome than some mothers. The recent advances in research with Asian parents also stressed the importance of cultural factors (Abas et al. 2013; Liu and Guo 2007, 2008; Wu et al. 2010; Xie et al. 2010).

Concerning the phenomenon of boomerang kids, research clearly indicates that the return of children to the home render the postparental transition more complex in its organization and its effects on parents (Hiedemann et al. 1998). Because the phenomenon of incompletely launched adults is increasing in scale, researchers should consider broadening their focus to the way all parents, including those who experienced a series of departures and returns, managed these changes. Accordingly, the conceptualization of the postparental stage should be reevaluated. If we wish to gain more knowledge on this period, a conceptualization that takes into account the complex process that leads to children’s independence should be adopted. Qualitative research may be an effective tool to capture the multifaceted dynamics associated with nest leaving and children’s return to the home (Ward and Spitze 2007).

Most marital and family research has focused on couples in childbearing and child rearing stages. Despite this fact, I believe that research to date on the empty nest constitutes important advances in our understanding of other periods of the family life cycle. With an aging population and the increased and persistent presence of emeritus parents living in nontraditional families, there is a growing need for studies on the empty nest, particularly with respect to examining mediators and moderators of the parental reaction. Emerging theories should be flexible enough to explain how a particular set of biological, social, and psychological circumstances interacts and results in a unique developmental path for emeritus parents.

References

Abas, M., Tangchonlatip, K., Punpuing, S., Jirapramukpitak, T., Darawuttimaprakorn, N., Prince, M., et al. (2013). Migration of children and impact on depression in older parents in rural Thailand, Southeast Asia. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 226–234.

Adelmann, P. K., Chadwick, K., & Baerger, D. R. (1996). Marital quality of black and white adults over the life course. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13, 361–384.

Ahlborg, T., Misvaer, N., & Möller, A. (2009). Perception of marital quality by parents with small children: A follow-up study when the firstborn is 4 years old. Journal of Family Nursing, 15, 237–263.

Anderson, S. A., Russell, C. S., & Schumm, W. R. (1983). Perceived marital quality and family life-cycle categories: A further analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 127–139.

Aquilino, W. S. (1991). Predicting parents’ experiences with coresident adult children. Journal of Family Issues, 12, 323–342.

Axelson, L. J. (1960). Personal adjustment in the postparental period. Marriage and Family Living, 22, 66–68.

Beaupré, P., Turcotte, P., & Milan, A. (2006). When is junior moving out? Transitions from the parental home to independence. Canadian Social Trends, 82, 9–15.

Borland, D. C. (1982). A cohort analysis approach to the empty-nest syndrome among three ethnic groups of women: A theoretical position. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44, 117–129.

Bozett, F. W. (1985). Male development and fathering throughout the life cycle. American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 41–54.

Bradbury, T. N., Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. (2000). Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 964–980.

Bumagin, V. E., & Hirn, K. F. (1982). Observations on changing relationships for older married women. American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 42, 133–142.

Cassidy, M. L. (1985). Role conflict in the postparental period: The effects of employment status on the marital satisfaction of women. Research on Aging, 7, 433–454.

Chen, D., Yang, X., & Aagard, S. D. (2012). The empty nest syndrome: Ways to enhance quality of life. Educational Gerontology, 38, 520–529.

Cherlin, A. J., Scabini, E., & Rossi, G. (1997). Still in the nest: Delayed home leaving in Europe and the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 18, 572–575.

Clemens, A. W., & Axelson, L. J. (1985). The not-so-empty-nest: The return of the fledgling adult. Family Relations, 34, 259–264.

Cole, C. L., & Cole, A. L. (1999). Boundary ambiguities that bind former spouses together after the children leave home in post-divorce families. Family Relations, 48, 271–272.

Condie, S. J., & Doan, H. T. (1978). Role profit and marital satisfaction throughout the family life cycle. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 9, 257–267.

Cooper, K. L., & Gutmann, D. L. (1987). Gender identity and ego mastery style in middle-aged, pre-, and post-empty nest women. The Gerontologist, 27, 347–352.

Crawford, M. P., & Hooper, D. (1973). Menopause, ageing and family. Social Science and Medicine, 7, 469–482.

Crowley, B. J., Hayslip, B., & Hobdy, J. (2003). Psychological hardiness and adjustment to life events in adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 10, 237–248.

D’Amore, S. (2009). Alcool et nid vide: Récit d’un travail thérapeutique avec un couple en crise de transition [Alcohol and empty nest: A case study of a couple in crisis]. Cahiers critiques de thérapie familiale et de pratiques de réseaux, 42, 231–254.

Dare, J. S. (2011). Transitions in midlife women’s lives: Contemporary experiences. Health Care for Women International, 32, 111–133.

Dennerstein, L., Dudley, E., & Guthrie, J. (2002). Empty nest or revolving door? A prospective study of women’s quality of life in midlife during the phase of children leaving and re-entering the home. Psychological Medicine, 32, 545–550.

Deutscher, I. (1964). The quality of postparental life: Definitions of the situation. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 26, 52–59.

Duvall, E. M., & Miller, B. C. (1985). Marriage and family development (6th ed.). New York: Harper and Row.

Dykstra, P. A., & Keizer, R. (2009). The wellbeing of childless men and fathers in mid-life. Ageing and Society, 29, 1227–1242.

Elder, G. H. (1998). The life course and human development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development. New York: Wiley.

Ellicott, A. M. (1985). Psychosocial changes as a function of family-cycle phase. Human Development, 28, 270–274.

Erickson, J. J., Martinengo, G., & Hill, E. J. (2010). Putting work and family experiences in context: Differences by family life stage. Human Relations, 63, 955–979.

Feeney, J., Peterson, C., & Noller, P. (1994). Equity and marital satisfaction over the family life cycle. Personal Relationships, 1, 83–99.

Finkel, J. S., & Hansen, F. J. (1992). Correlates of retrospective marital satisfaction in long-lived marriages: A social constructivist perspective. Family Therapy, 19, 1–16.

Glenn, N. D. (1975). Psychological well-being in the postparental stage: Some evidence from national surveys. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 37, 105–110.

Gorchoff, S. M., John, O. P., & Helson, R. (2008). Contextualizing change in marital satisfaction during middle age. Psychological Science, 19, 1194–1200.

Gutmann, D. L. (1985). The parental imperative revisited: Towards a developmental psychology of adulthood and later life. Contributions to Human Development, 14, 31–60.

Hagen, J. D., & DeVries, H. M. (2004). Marital satisfaction at the empty-nest phase of the family life cycle: A longitudinal study. Marriage and Family: A Christian Journal, 7, 83–98.

Hansen, T., Slagsvold, B., & Moum, T. (2009). Childlessness and psychological well-being in midlife and old age: An examination of parental status effects across a range of outcomes. Social Indicators Research, 94, 343–362.

Harkins, E. B. (1978). Effects of empty nest transition on self-report of psychological and physical well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 40, 549–556.

Harris, R. L., Ellicott, A. M., & Holmes, D. S. (1986). The timing of psychosocial transitions and changes in women’s lives: An examination of women aged 45–60. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 409–416.

Hershberger, B. (1982). Living in the freedom there is. Activities, Adaptation and Aging, 2, 51–58.

Hiedemann, B., Suhomlinova, O., & O’Rand, A. M. (1998). Economic independence, economic status, and empty nest in midlife marital disruption. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 219–231.

Hobdy, J., Hayslip, B., Kaminski, P. L., Crowley, B. J., Riggs, S., & York, C. (2007). The role of attachment style in coping with job loss and the empty nest in adulthood. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 65, 335–371.

Holahan, C. K. (1984). Marital attitudes over 40 years: A longitudinal cohort analysis. Journal of Gerontology, 39, 49–57.

Kapitus, C. A., & Johnson, M. P. (2003). The utility of family life cycle as a theoretical and empirical tool: Commitment and family life-cycle stage. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 155–184.

Kumagai, F. (2010). Forty years of family change in Japan: A society experiencing population aging and declining fertility. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41, 581–610.

Lachman, M. E. (2004). Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 305–331.

Leopold, T., Geissler, F., & Pink, S. (2012). How far do children move? Spatial distances after leaving the parental home. Social Science Research, 41, 991–1002.

Lewis, R. A., & Duncan, S. F. (1991). How fathers respond when their youth leave and return home? Prevention in Human Services, 9, 223–234.

Lippert, L. (1997). Women at midlife: Implications for theories of women’s adult development. Journal of Counseling and Development, 76, 16–22.

Liu, L., & Guo, Q. (2007). Loneliness and health-related quality of life for the empty nest elderly in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Quality of Life Research, 16, 1275–1280.

Liu, L., & Guo, Q. (2008). Life satisfaction in a sample of empty-nest elderly: A survey in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Quality of Life Research, 17, 823–830.

Mackey, R. A., & O’Brien, B. A. (1999). Adaptation in lasting marriages. Families in Society, 80, 587–596.

Major, D. A., & Germano, L. M. (2006). The changing nature of work and its impact on the work-home interface. In F. Jones, R. J. Burke, & M. Westman (Eds.), Work-life balance: A psychological perspective (pp. 13–38). New York: Psychology Press.

McFarland, C., Ross, M., & DeCourville, N. (1989). Women’s theories of menstruation and biases in recall of menstrual symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 522–531.

McQuaide, S. (1998). Women at midlife. Social Work, 43, 21–31.

Menaghan, E. (1983). Marital stress and family transitions: A panel analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 371–386.

Mitchell, B. A., & Lovegreen, L. D. (2009). The empty nest syndrome in midlife families: A multimethod exploration of parental gender differences and cultural dynamics. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 1651–1670.

Neugarten, B. L. (1976). Adaptation and the life cycle. Counseling Psychologist, 6, 16–20.

Nomaguchi, K. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2003). Costs and rewards of children: The effects of becoming a parent on adults’ lives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 356–374.

Pryor, J. (1999). Waiting until they leave home: The experiences of young adults whose parents separate. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 32, 47–61.

Radloff, L. S. (1980). Depression and the empty nest. Sex Roles, 6, 775–781.

Raup, J. L., & Myers, J. E. (1989). The empty nest syndrome: Myth or reality? Journal of Counseling and Development, 68, 180–183.

Resnick, J. L. (1979). Women and aging. The Counseling Psychologist, 8, 29–30.

Rodgers, R. H., & Witney, G. (1981). The family cycle in twentieth century Canada. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 43, 727–740.

Rogers, L. P., & Markides, K. S. (1989). Well-being in the postparental stage in Mexican-American women. Research on Aging, 11, 508–516.

Rollins, B. C., & Cannon, K. L. (1974). Marital satisfaction over the family life cycle: A reevaluation. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 36, 271–282.

Rollins, B. C., & Feldman, H. (1970). Marital satisfaction over the family life cycle. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 32, 20–28.

Schmidt, P. J., Murphy, J. H., Haq, N., Rubinow, D. R., & Danaceau, M. A. (2004). Stressful life events, personal losses, and perimenopause-related depression. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 7, 19–26.

Schnaiberg, A., & Goldenberg, S. (1989). From empty-nest to crowded nest: The dynamics of incompletely-launched young adults. Social Problems, 36, 251–269.

Schram, R. W. (1979). Marital satisfaction over the family life cycle: A critique and proposal. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 7–12.

Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2006). Leaving home or still in the nest? Parent-child relationships and psychological health as predictors of different leaving home patterns. Developmental Psychology, 42, 864–876.

Settersten, R. A. (1998). A time to leave home and a time never to return? Age constraints on the living arrangements of young adults. Social Forces, 76, 1373–1400.

Sheriff, M., & Weatherall, A. (2009). A feminist discourse analysis of popular-press accounts of postmaternity. Feminist and Psychology, 19, 89–108.

Su, D., Wu, X., Zhang, Y., Li, H., Wang, W., Zhang, J., et al. (2012). Depression and social support between China’ rural and urban empty-nest elderly. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55, 564–569.

Sussman, M. B. (1955). Activity patterns of post-parental couples and their relationship to family continuity. Marriage and Family Living, 17, 338–341.

Tucker, P., & Aron, A. (1993). Passionate love and marital satisfaction at key transition points in the family life cycle. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 12, 135–147.

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. (2003). Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 574–583.

Umberson, D., Pudrovska, T., & Reczek, C. (2010). Parenthood, childlessness, and well-being: A life course perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 612–629.

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Powers, D. A., Chen, M. D., & Campbell, A. M. (2005). As good as it gets? A life course perspective on marital quality. Social Forces, 84, 493–511.

Vaillant, C. O., & Vaillant, G. E. (1993). Is the U-curve of marital satisfaction an illusion? A 40-year study of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 230–239.

VanLaningham, J., Johnson, D. R., & Amato, P. (2001). Marital happiness, marital duration, and the U-shaped curve: Evidence from a five-wave panel study. Social Forces, 78, 1313–1341.

Wang, J., & Zhao, X. (2011). Empty nest syndrome in China. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58, 110.

Wang, J., & Zhao, X. (2012). Family functioning, social support, and quality of life for Chinese empty nest older people with depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27, 1204–1206.

Ward, R. A., & Spitze, G. D. (2007). Nestleaving and coresidence by young adult children: The role of family relations. Research on Aging, 29, 257–277.

White, L. (1994). Coresidence and leaving home: Young adults and their parents. Annual Review of Sociology, 20, 81–102.

White, L., & Edwards, J. N. (1990). Emptying the nest and parental well-being: An analysis of national panel data. American Sociological Review, 55, 235–242.

Wong, Y. C., & Leung, J. (2012). Long-term care in China: Issues and prospects. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 55, 570–586.

Wu, Z., Sun, L., Sun, Y., Zhang, X., Tao, F., & Cui, G. (2010). Correlation between loneliness and social relationship among empty nest elderly in Anhui rural area, China. Aging and Mental Health, 14, 108–112.

Xie, L., Zhang, J., Peng, F., & Jiao, N. (2010). Prevalence and related influencing factors of depressive symptoms for empty-nest elderly living in the rural area of YongZhou, China. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 50, 24–29.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bouchard, G. How Do Parents React When Their Children Leave Home? An Integrative Review. J Adult Dev 21, 69–79 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-013-9180-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-013-9180-8