Abstract

Children with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) present with challenges in social cognitive ability, Research comparing PWS to ASD is important given the implication of 15q11-q13 region in the biology of autism. However, recent findings question the accuracy of relying solely on parent report in behavioral characterization. Thus, this study examined social cognition in an observable pretend play task and by parent report in 50 preschool children (ages 3–5) with PWS, by subtype, compared to ASD. Behaviorally, the paternal deletion subtype expressed overall higher functioning, whereas the maternal uniparental disomy subtype performed more similarly to the ASD group. Results are the first to show deficits in social cognitive ability early in development. The severity and differences in deficits between PWS subtypes are important in informing early intervention efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Previous research indicates that children with Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS), a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by alterations to 15q11-q13, present with challenges in social cognitive ability, defined as an individual’s stable pattern of processing social information and regulating emotions. Overall, typical trajectories of social cognitive development cause children to develop important skills such as joint attention and facial and emotional processing, which foster new social encounters and heightened awareness and interest in other people (Choudhury et al. 2006). This leads children to seek out social interaction from parents and peers in continuing to develop socioemotional skills (Olson and Dweck 2008). In this regard, research has shown that children with PWS show deficits across symbolic play, parent–child interactions, emotion regulation, and rigid and restrictive behaviors that influence their ability to seek out social engagement and build quality relationships throughout early development (Dimitropoulos et al. 2013; Dimitropoulos and Schultz 2007; Dykens et al. 2017; Zyga et al. 2015).

It is also well established that individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) show pervasive deficits in social cognition (Geschwind and Levitt 2007; Hobson and Lee 1999). These deficits have led to significant functional impairment and overall decreased quality of life, not only for individuals with ASD, but also their family members (Gray 2006; Higgins et al. 2005). In particular, social cognition research in autism has focused on theory of mind, imitation, joint attention, eye gaze processing, pretend play, emotional processing, and social engagement (Geschwind and Levitt 2007; Hobson and Lee 1999; Senju 2013). Consistent lines of research have found that individuals with ASD show deficits across social cognitive domains that present early in development (Senju 2013). Specifically, preschoolers with ASD show social attention impairments in social orienting, joint attention, and attention to other’s distress that are more severe than mentally-aged matched children who present with developmental or intellectual delay alone (Dawson et al. 2004). In addition, individuals with ASD have been characterized as having deficits in understanding and engaging in the pragmatics of social interactions, such as turn-taking, distancing, greetings, regulating volume of voice, a tendency to dwell on certain topics, and difficulty understanding and expressing emotions (White et al. 2007). Taken together, these social deficits make it difficult for children with ASD to engage with parents or peers and also for parents and peers to engage with children who have ASD who may appear disinterested or unmotivated. This disconnect in interactions makes reciprocal engagement difficult in this population, which can negatively impact development through limited parent–child and peer bonding (Dawson et al. 2004; White et al. 2007).

Research comparing PWS to ASD is important considering the implication of alterations in the 15q11-q13 region to the behavioral phenotype in both of these disorders and how this may relate to the underlying biology of autism (Dimitropoulos and Schultz 2007; Dykens et al. 2017). In particular, maternal duplications of this genomic region are the most common cytogenetic abnormality found in association with idiopathic autism (Nurmi et al. 2003). Further, individuals with PWS who express the disorder via maternal uniparental disomy (mUPD) have been shown to be at greater risk for autistic symptomotology than individuals with PWS by paternal deletion (DEL) of 15q11-q13 (Hogart et al. 2010). For example, individuals with the mUPD subtype of PWS scored similarly to children with ASD in domains such as social cognition, communication, and motivation (Dimitropoulos et al. 2013). In addition, individuals with PWS, regardless of subtype, showed decreased social competence with scores on the Social Competence Inventory (SCI; Rydell et al. 1997) falling below the validation sample’s group mean scores.

However, more recent research findings call into question the accuracy of relying solely on parent report, which may lead to disparities when comparing these measures to clinical assessment in evaluating autism symptomology in PWS—a phenomenon that is known to occur in the general population with parents over-reporting concerns for ASD (Bennett et al. 2017; Blumberg et al. 2013; Dykens et al. 2017). A study conducted by Dykens et al. (2017) assessed the presence of ASD in 146 children with PWS, ages 4–21 years, using both the autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS-2), administered by a clinician, and the social communication questionnaire (SCQ), completed by a parent, along with other measures of adaptive functioning. Study results showed that clinician determined diagnoses were made in 18 children (12.3% of the sample) versus a 29–49% chance of screening positive for ASD by the parent completed SCQ. Bennett et al. (2017) showed similar findings across a much smaller sample of 10 children with PWS, ages 3–12, with 8 out of 10 participants exceeding cut-off scores for ASD based on parent report yet no assigned clinical diagnoses based on ADOS assessment. Both studies note that this lack of agreement suggests that the sole use of screeners or parent measures should be avoided and that children with PWS need to be directly observed by clinicians and evaluated so the complexity of interpreting ASD symptoms and functioning in this population can be fully captured (Bennett et al. 2017; Dykens et al. 2017).

In using behavioral assessment to better understand functioning, Zyga et al. (2015) found that children with PWS, ages 6–9, showed significantly lower play abilities across various domains as compared to typical development. Further, deficits in play ability evidenced in the PWS sample did not differ from a sample of children with ASD. Overall, children with PWS spent a majority of their time not engaging in play during a solitary play period, displaying low levels of imagination, organized storylines, and affect expression in play. However, the addition of a play partner, who could structure the play scenario, led to significant increases across almost every domain in the PWS sample, whereas children in the ASD sample only showed increases in affect expression with the addition of the same play partner (Zyga et al. 2015).

These findings imply that some of the social cognitive deficits evidenced in PWS may be similar to ASD but also may differ in important ways and be more malleable to change. Although recent findings suggest a lower prevalence of ASD in the PWS population than previously reported (i.e. 12.3% versus previous findings of 25–41%), a large proportion of children with PWS still exhibit significant difficulties in social interaction that impact daily functioning and later development (Bennett et al. 2017; Dykens et al. 2017). This indicates the need for further characterization of social cognitive ability in PWS, especially by subtype and in younger populations, where minimal research has been conducted. Further, of the research that has been conducted on social functioning across wide age ranges in PWS, most has been limited to parent report instead of measuring observable behavior. A better understanding of how deficits present early in development, not only through report but also clinician-observed behavior, can inform the need for intervention and how to best tailor it to PWS subtype, especially given the more recent findings of disparity between parent report of functioning and clinical evaluations.

Thus, the current study sought to better characterize early social cognitive ability both in an observable pretend play task and by parent report in preschoolers (ages 3–5) with PWS, by subtype, in comparison to ASD. As a note, the current paper defined social cognition as an overarching construct that encompasses various domains, including pretend play and other aspects of socioemotional functioning. Pretend play ability was measured as a component of social cognition in that the use of the play task evaluated ability areas relating to pretense, emotional expression, and interpersonal processes. A second aim of the study was to better understand how other areas of development, such as receptive language (PPVT), autism severity (SCQ), and social skills development (SSIS) related to pretend play ability in both the PWS and ASD samples.

Taken together, past research has shown that, by parent report, children with PWS function lower than TD peers in social domains yet do not present as impaired as individuals with ASD (Dimitropoulos et al. 2013; Tager-Flusberg and Sullivan 2000). It is important to confirm these findings using direct observation in tasks that measure social cognitive ability in early development and to understand how functioning by subtype may differ, both in parent report and behavioral assessment. For the first aim, it was hypothesized that children with both genetic subtypes of PWS would show deficits in social cognitive functioning by parent report and observable behavior, as compared to a typical norm reference sample. Further, the mUPD subtype of PWS was predicted to show deficits that were more similar to the ASD sample than those with the DEL subtype in social cognitive functioning. For the second aim, it was predicted that groups with more impacted play ability (i.e. mUPD and ASD) would also show more autistic symptomatology and decreased receptive language and social skills functioning.

Methods

Participants

Fifty children (30 PWS; 20 ASD) between the ages of 3–5 years participated in the current study. Participants were included in the study if they were minimally verbal (i.e. able to produce phrased speech), able to sit at a table for short periods of time to complete tasks, and were not engaged in any clinical trials that aimed to alter mood, behavior, or social engagement. Further, participants with PWS were required to provide confirmation of their genetic diagnosis and participants with ASD were required to provide documentation of a primary diagnosis of autism from a pediatrician, clinical psychologist, psychiatrist, or pediatric neurologist. Further, participants in the ASD group had a mental age > 2 years as defined by the MSEL visual reception age equivalents which allowed for an evaluation of SCQ criteria in the current sample. Parent report showed that all children with ASD scored above the SCQ cut-off (> 15) which confirmed elevated risk of autism. In addition to the PWS and ASD participants, data on 26 typically developing children were collected in the current study and were used primarily as a norm reference group. Direct comparisons were made when group functioning across samples warranted comparison with the TD reference group. Children in the TD sample were age and ethnicity matched to both the PWS and ASD groups (3–5 years of age; majority Caucasian). The TD sample had a more even split in gender to reflect the general population (53.8% male) and scored within the average range in cognitive functioning (MSEL-VRS) and above average in receptive language ability (PPVT). Children were excluded from the TD group if they had any previous diagnosis of developmental, behavioral, or learning disorder or disability. See Table 1 for full demographic information. Participants with PWS were recruited nationally as part of a lager project through the Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (FPWR) and Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (PWSA). Participants for the ASD group were recruited through local preschools, autism organizations, and nationally through Autism Speaks. Lastly, TD participants were recruited locally through university and community online postings.

Measures

Cognitive and Adaptive Functioning

Mullen Scales of Early Learning—Visual Reception Subscale (MSEL; Mullen 1995)

An individually administered assessment which measures functioning in infants and children up to 68 months of age across five domains (gross motor, visual reception, fine motor, expressive language, and receptive language). In the current study, only the visual reception subscale was administered and T-scores for this scale are reported given that previous research has shown that it is a valid and reliable indicator of early cognitive ability across typical and atypical populations (Bishop et al. 2011).

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition (PPVT-4; Dunn and Dunn 2007)

An individually administered measure of receptive vocabulary for standard American English for ages 2 years 6 months to 90 + years. The measure has shown good validity and reliability across both typical and atypical populations (Dunn and Dunn 2007). Overall receptive language ability is reported as a Standard Score (M = 100; SD = 15).

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (Vineland—II; Sparrow et al. 2005)

A parent/caregiver rating form that reports on a child’s ability across five domains (communication, daily living skills, socialization, motor skills, and maladaptive behavior including internalizing and externalizing behaviors). Standard scores (M = 100; SD = 15) are produced for each domain and the measure is appropriate for individuals’ birth-90 years of age.

Social Cognitive Ability

Child Assessment

Affect in Play Scale—Preschool Version (APS-P, Kaugars and Russ 2009; Russ and Association 2014)

A standardized play task designed to measure various dimensions of children’s pretend play and validated for preschool children ages 4–5 years. This study extended its use to 3-year-old children, which has reliably been done in previous work (Marcelo and Yates 2014; Yates and Marcelo 2014). Given the relative rarity of PWS, the ability to expand the age range to include 3 year olds would allow for a larger sample size and better characterization of functioning across a larger preschool age range. In this task, various toys are laid out on a table (cups, stuffed animals, toy car) and children are provided with a story stem and instructions to play with the toys and talk out loud for a 5-min period. The play is videotaped and then scored according to a detailed manual that assessed both cognitive and affective processes in the play narrative (Kaugars and Russ 2009).

The child’s play is scored using a criterion-based rating scale. For this study, a modified version of the APS-P scoring system was used, which included eight original variables in addition to seven variables created to better measure higher levels of pretense ability and interpersonal domains in pretend play. The original variables included ones that captured cognitive processes in play, specifically: (1) Organization of the storyline, (2) Imagination ability to pretend, and (3) Comfort in playing with the toys. These variables were all scored on a 1–5 scale; one being the lowest ability in that domain. Original variables that measured affective processes included: (1) Frequency of Affect, a total frequency count of affect units expressed within the play narrative and (2) Variety of Affect, a total count of the number of affect categories out of 11 possible categories expressed during the play. Affect scores relate to child’s ability to have mental representations of emotions and then express these emotions in play. For example, a child may recognize that a character is happy to play with another toy during their story and will voice this through expressing “Yay, this is fun!” or having the toys hug. Further, for each 20-s interval, the rater indicates which of three types of play (No Play; Functional Play; Symbolic Play) was the predominant activity – i.e. occurred for greater than or equal to 10 s within each 20-s interval. No Play is defined as the child not moving or interacting with the toys. Functional Play relates to a child making simple, repetitive muscle movements with the toys. Symbolic Play is defined as any instance of using toys in an “as-if” manner, substituting an object for another, or using the object in any way other than how it is intended. Symbolic play was differentiated from stereotyped play in that it had to occur in a sequence of events (i.e. placing bears head into cup while making chewing noise to symbolize eating; placing animal on car and flying around in the air) and the child did not either spend the majority of time engaging in the play act and/or the child did not repeat the act more than twice with the same set of toys.

The additional variables were conceptualized from the literature and previous research focused on more accurately measuring symbolic and interpersonal processes in pretend play (Seja and Russ 1999) and also from observation of the recorded play task, which allowed for detailed analysis of participants’ play behaviors above and beyond assigning scaled score values. The added variables allowed for a more descriptive rating system of the original variables and measured constructs in play in a more specific manner. For example, transformations and substitutions are two criteria encompassed in measuring the imagination of a child’s pretend play. In the original Imagination score on the APS-P, these concepts were part of the 5-point rating system whereas the added transformation and substitution variables allowed for the more specific coding of the actual frequency of these instances in play. This allowed for pretend play ability to be better described and characterized in the current sample. Further, as reported in the results section, reliability for these new variables was high between independently trained coders suggesting these variables can be accurately identified and measured. The first additional variable included a frequency count of symbolic substitutions a child displayed during the 5-min play task. A symbolic substitution was defined as when a child used a toy in a way that was similar to the properties of the toy, yet still imagined it was something else. For example, the ball as a sun or the cup as a bowl. This occurs when the object used for a substitution shared some type of overlap in its shape, size, or consistency with the imagined object. The second variable measured the frequency count of symbolic transformations a child made during the 5-min play period. A symbolic transformation was defined as when a child used a toy in a completely “as-if” manner that did not relate to the original properties of that toy. For example, using a cup as a rocket ship or imagining that there are other objects present (i.e. the table is the road; over here is the house). The other five variables measured aspects relating to interpersonal processes in pretend play, namely: (1) frequency count of personification of the toys (i.e. any instance of when human attributes were attributed to the toys during the 5-min play task), (2) frequency count of the number of cooperative/nurture interactions that occur between the toys, (3) frequency count of the number of aggressive/negative interactions that occur between the toys, (4) frequency count of the number of neutral interactions that occur between the toys, and (5) frequency count of the total number of interpersonal acts included in their play period.

Taken together, the Cognitive Domain encompassed eight variables—Imagination, Comfort, Organization, Time in No Play, Time in Functional Play, Time in Symbolic Play, Frequency of Substitutions, and Frequency of Transformations. The Affective Domain encompassed two variables—Affect Frequency and Affect Variety. Lastly, the Interpersonal Domain encompassed five variables—Frequency of Personifications, Frequency of Aggressive Interpersonal Acts, Frequency of Nurture/Affectionate Interpersonal Acts, Frequency of Neutral Acts, and Total Number of Interpersonal Acts.

Kaugars and Russ (2009) have developed a detailed scoring manual for the original eight variables that measure cognitive and affective domains included in the APS-P. Zyga, Dimitropoulos, and Russ created an additional coding system for the symbolic and interpersonal variables. Past research has shown that interrater reliability across all original variables is high, consistently in the 80s and 90s. Internal consistency for the affect scores on the APS-P using the Spearman-Brown split-half reliability is also high (0.85). The APS-P has a growing body of validity studies demonstrating associations with theoretically relevant criteria (see Kaugars and Russ 2009; Yates and Marcelo 2014; Fehr and Russ 2013, 2016; Russ and Association 2014). Analyses conducted across age ranges (one-way ANCOVAs controlling for cognitive ability) showed no difference in play ability between 3, 4, and 5 year olds on all variables, except for neutral interpersonal acts (F = 3.59; p = 0.02) where both 3 and 4 year olds performed lower than 5 year olds. Further, partial correlations across each age showed that all APS-P variables (original and new) significantly inter-correlated with one another and also significantly correlated with constructs previously shown to be related to pretend play ability (i.e. social skills, empathy, cooperation from the SSIS).

Parent Report

Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scales (SSIS; Gresham and Elliott 2008)

A parent/caregiver survey that evaluates social skills, problem behaviors, and academic competence in children ages 3–18 years of age. The measure includes 12 subscales (communication, cooperation, assertiveness, responsibility, empathy, engagement, self-control, externalizing, bullying, hyperactivity/inattention, internalizing, and autism spectrum) and an overall standard score with national norms for preschool age children. Standard scores and behavior levels (below average, average, above average) are given for each subscale. Reliability and validity evidence has been collected for its use in special populations (Gresham and Elliott 2008).

Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Rutter et al. 2003)

A brief instrument completed by a parent/caregiver that evaluates communication skills and social functioning in screening for an ASD. The survey provides a global cut-off score of 15 with scores above this value indicating a high probability of autism. It is appropriate for use on children with a mental age over 2.0 years and has been shown to be an efficient, valid, and reliable way to obtain diagnostic information or screen for autistic symptoms (Rutter et al. 2003).

Results

Data Analysis Plan

For each measure administered in the current study, scores from the TD group are provided as normative reference and in analyses where direct comparisons are warranted given the primary results. Primary analysis was conducted comparing variables of interest across the DEL, mUPD, and ASD groups. If significant differences were evident, post hoc analyses were conducted to better understand these differences. Cognitive ability was controlled for across all group analyses. Further, given the number of analyses conducted, Bonferroni correction procedures were used to correct for multiple comparisons. All reported alphas account for this adjustment.

Interrater reliability for the APS-P: Undergraduate and graduate research assistants were trained by the second author based on the standardized APS-P manual. Once reliability was obtained on training videos across typical and atypical samples (IRR = 0.80–0.90), two independent coders, blind to conditions, rated videos from the current sample. Twenty percent of the APS-P videos across groups were double-coded to ensure reliability. Intra-class correlations (ICC) were calculated based on a single measure, absolute agreement, two-way mixed effects model to assess the degree of consistency between coders for each task. The resulting ICCs for all original and new variables on the APS-P were Excellent (IRR = 0.80–0.90; Cicchetti 1994). Raters had overall high levels of agreement and rated behaviors consistently across participants.

Demographics

Within the PWS sample, 17 participants had a confirmed diagnosis of DEL subtype, 12 had a confirmed diagnosis of mUPD, and one participant’s genetic subtype status was unknown. Participants across the DEL, mUPD, and ASD samples did not differ on age (M = 4.35; SD = 0.87) or PPVT (M = 83.11; SD = 18.01). However, there was a significant difference in cognitive ability (F = 3.31; p = 0.05) as measured by the visual reception subscale on the MSEL, with the mUPD sample having the lowest score, which significantly differed from the DEL group (p = 0.04) but did not differ from the ASD group (p = 0.44). Further, the PWS sample presented with a more even gender distribution (DEL = 52.9% male; mUPD = 69.2% male) whereas the ASD group (80% male) had a higher percentage of male participants which more accurately reflects gender distribution in this population. The groups did not differ on race (majority Caucasian). For adaptive functioning, children with ASD were reported to show significantly lower skills of daily living (F = 3.29; p = 0.05), socialization skills (F = 15.24; p < 0.001), and total adaptive ability (F = 3.69; p = 0.03) as measured by the VABS as compared to the DEL sample. The mUPD sample did not significantly differ from either the DEL or ASD on any domains measured on the VABS. See Table 1 for full details.

Pretend Play Ability

APS-P

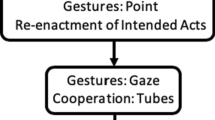

A series of one-way ANCOVAs, controlling for cognitive ability, were conducted to better understand how global scores reflecting social cognitive and affective ability in pretend play differed across the DEL, mUPD, and ASD groups based on the standardized play task administered as part of the current study. Results showed that the three groups significantly differed on Organization (F = 4.45; p = 0.02), Affect Frequency (F = 4.99; p = 0.01), Time spent in Functional Play (F = 3.97; p = 0.03), Time spent in Symbolic Play (F = 6.25; p = 0.004), Number of Aggressive Interpersonal Acts (F = 3.41; p = 0.04), Number of Divergent Storylines (F = 3.16; p = 0.05), and Frequency of Substitutions (F = 3.74; p = 0.03).

Post-hoc analyses indicated that, overall, the DEL subtype performed the highest on all of the measures and more similarly to the TD reference group. The mUPD and ASD groups had more similar functioning across the variables, with the mUPD presenting as more impacted than the DEL group on Organization and Time spent in Symbolic Play: both the mUPD (p = 0.05; p = 0.007) and ASD (p = 0.04; p = 0.02) groups scored significantly lower than the DEL sample. Further, the mUPD sample expressed significantly less Affect (p = 0.01) and Interpersonal Aggressive Acts (p = 0.04) than the DEL sample and the mUPD and ASD samples did not differ in these domains (p = 1.00; p = 0.69). Lastly, the ASD sample spent significantly more Time in Functional Play (p = 0.02) and performed significantly less Substitutions (p = 0.04) than the DEL subtype. The mUPD did not differ from the ASD sample in these domains. See Table 2 for full details.

Given the results that the DEL subtype performed highest across measures of pretend play ability detailed above, subsequent analyses were conducted to better understand how mean scores in this group compared to the typical sample. When controlling for cognitive ability, the DEL subtype only differed from the TD group on Time Spent in No Play (F = 4.31; p = 0.045), Personifications (F = 11.32; p = 0.002), and Neutral Interpersonal Acts (F = 4.66; p = 0.038). Across all three of these variables, the DEL sample exhibited lower performance than the TD group. There were no other significant differences on pretend play variables between these two groups.

Social Cognitive Ability

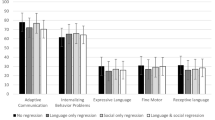

SSIS

A series of one-way ANCOVAs, controlling for cognitive ability, were conducted to better understand how social skills functioning differed across the three groups. The SSIS total standard score significantly differed between groups (F = 13.59; p < 0.001). Subdomain differences included: Communication (F = 16.52; p < 0.001), Cooperation (F = 10.21; p < 0.001), Assertiveness (F = 7.67; p = 0.001), Responsibility (F = 11.68; p < 0.001), Empathy (F = 10.68; p < 0.001), Engagement (F = 9.82; p < 0.001), Self-Control (F = 7.47; p = 0.002), Bullying (F = 4.00; p = 0.03), Hyperactivity/Inattentiveness (F = 5.21; p = 0.009), and Autism Behaviors (F = 11.03; p < 0.001).

Follow-up post hoc analysis indicated that the ASD sample scored lower across all SSIS domains whereas the DEL and mUPD sample did not differ on their level of reported functioning. Specifically, the ASD sample was reported to have more significant deficits in domains relating to Responsibility (p = 0.002), Empathy (p = 0.03), Self-Control (p = 0.01), Autism Behaviors (p = 0.002), and the Total Standard Score (p = 0.003) in comparison to both the DEL and mUPD groups. Further, the ASD group was reported to perform worse in Communication (p < 0.001), Cooperation (p < 0.001), Assertiveness (p < 0.001), Engagement (p < 0.001), and Hyperactivity/Inattentiveness (p = 0.02) as compared to the DEL and engaged in more Bullying activities than the mUPD group (p = 0.03). See Table 3 for full details.

SCQ

A one-way ANCOVA, controlling for cognitive ability, was conducted to compare scores on the SCQ across the three groups. SCQ Global Score differed across groups (F = 11.59; p < 0.001). Specifically, the ASD group had a mean score (M = 17.05; SD = 5.67) above the SCQ severity cut-off score of 15, which was significantly more elevated than the DEL sample (p < 0.001). The mUPD sample (M = 11.85; SD = 7.93) did not differ from either the DEL sample, whose score fell well below the severity cut-off (M = 7.44; SD = 3.35) and the ASD sample. See Table 3 for full details.

Within-Group Correlations

In order to better understand any unique relationships among parent report, behavioral assessment, and other domains of functioning, specifically in how receptive language (PPVT), autism severity (SCQ), and social skills (SSIS) related to pretend play (APS-P), a series of within-group correlations were conducted.

Receptive Language (PPVT) × Pretend Play (APS-P)

PWS Subtype: DEL

Receptive language ability did not significantly correlate with any of the five original APS-P variables. However, there was a trending relationship between receptive language and Affect Frequency (r = 0.45; p = 0.09) in this group. These results were similar to the TD reference group, which only showed a relation between language ability and one play variable (see Table 4).

PWS Subtype: mUPD

Similarly, receptive language ability did not significantly correlate with any of the five original APS-P variables among children with mUPD.

ASD

Receptive language ability positively correlated with APS-P Comfort (r = 0.57; p = 0.01), Organization (r = 0.51; p = 0.02), and Affect Frequency (r = 0.53; p = 0.02). Further, there were trending relationships between receptive language ability and Imagination (r = 0.45; p = 0.06) and Affect Categories (r = 0.43; p = 0.08). The pattern of correlation between receptive language and play ability in the ASD differed from the TD reference group and the PWS subtypes in that there were significant or trending relationships between all five original APS-P variables and language ability (see Table 4).

Autism Severity (SCQ) × Pretend Play (APS-P)

PWS Subtype: DEL

Autism severity as measured by parent report (SCQ) did not correlate to pretend play ability in the DEL sample. These findings are commensurate with the TD norm sample, which showed no significant correlations between the SCQ and play ability (see Table 5).

PWS Subtype: mUPD

In contrast to the DEL and TD reference groups, bivariate correlational analysis in the mUPD sample showed significant negative relationships between Organization (r = − 0.57; p = 0.04) and Comfort (r = − 0.58; p = 0.04) and autism severity (see Table 5).

ASD

No significant correlations were found between autism severity and pretend play ability (see Table 5) within the ASD sample.

Social Skills (SSIS) × Pretend Play (APS-P)

PWS Subtype: DEL

When evaluating parent report of social skills and their relationship to pretend play ability, the DEL group showed no significant correlations across the SSIS domains, which was consistent with the TD norm reference group (see Table 6).

PWS Subtype: mUPD

In contrast to the DEL and TD groups, the mUPD sample showed positive correlations between Organization in play and Cooperation (r = 0.56; p = 0.05) and Overall Social Functioning (r = 0.55, p = 0.01). Further, Affect Frequency in play was positively correlated with Engagement in this group (r = 0.58; p = 0.04) (see Table 6).

ASD

In comparison to the other samples, children with ASD showed multiple correlations between social skills by parent report and pretend play ability. Specifically, this sample showed positive relationships between Imagination in play and Empathy (r = 0.47, p = 0.04), Engagement (r = 0.57; p = 0.01), and Overall Social Functioning (r = 0.44; p = 0.05). Organization in play significantly positively correlated with Engagement (r = 0.47; p = 0.04). Affect Frequency in play also significantly related to Engagement (r = 0.58; p = 0.01). Lastly, Affect Categories in play significantly positively correlated with Empathy (r = 0.72; p < 0.001), Engagement (r = 0.72; p < 0.001), and Overall Social Functioning (r = 0.56; p = 0.01).

Discussion

The current study characterized early social cognitive ability based on parent report and behavioral assessment in preschoolers with PWS, by genetic subtype, in comparison to ASD. A further aim was to understand what deficits were specific to each PWS subtype during early childhood, above and beyond what may be expected given developmental or cognitive delays, and if the presence of these deficits differed by parent report versus observable behavior. Particularly, a pretend play assessment (APS-P), which measured aspects of early social cognitive ability, was administered along with parent report surveys, which measured domains relating to autism severity/social communication (SCQ) and cooperation, assertiveness, empathy, engagement, levels of self-control, and maladaptive behaviors such as internalizing/externalizing behaviors and those associated with hyperactivity or autism spectrum traits (SSIS). To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate social cognitive ability using direct assessment and parental report in PWS and in comparison to autism during the preschool years.

Primary findings indicate that the DEL and mUPD groups significantly differed from one another in functioning across a number of domains by parent report and behavioral assessment. On behavioral assessments, the DEL sample expressed overall higher functioning and the mUPD group presented with performance more similar to the ASD group across certain measures. However, results from parent report were not consistent with these findings. Particularly, parents reported that both subtypes of PWS were performing at a higher level than the ASD sample across all social cognitive domains. Another important finding was that, for all measures, these results held when controlling for cognitive ability, suggesting the relationships between social cognitive ability and pretend play are specific to each genetic subtype rather than what would be expected from developmental delay alone. Lastly, partial correlations within DEL, mUPD, and ASD groups showed associations between receptive language and parent report of autism severity and social skills with performance on the APS-P, unique to each sample.

Comparison Across Groups

Taken together, the results of this study present a consistent pattern of functioning across both behavioral assessment and parent report where the DEL subtype of PWS performed higher than both the mUPD and ASD samples. This higher ability in the DEL group was evident across receptive language and cognitive ability as measured by the MSEL along with measures in pretend play and parent report of social cognitive functioning. An important finding to note is that on the pretend play assessment, the DEL and mUPD subtypes did significantly differ on organization and time spent in symbolic play whereas, by parent report, the DEL group had higher mean scores across social functioning that were not statistically different than the mUPD group. This suggests that there are true differences between the groups that may be better captured by behavioral observation rather than parent report alone. Another novel finding from this study was that the DEL group scored more similarly to the TD comparison group than the mUPD or ASD groups in pretend play ability on the APS-P. This finding again suggests that, at this early age, the PWS subtypes do indeed show meaningful differences in ability with what would be expected with regard to typical development.

Examining performance between the mUPD and ASD groups shows a more comparable profile of performance, with the mUPD group consistently scoring slightly higher (nonsignificant) than the ASD sample yet lower than the DEL sample. However, there were some instances, specifically in the APS-P, where the mUPD sample performed more poorly than both the DEL and ASD groups, such as, on average, spending twice as much time not engaging with the toys (‘no play’ variable) and expressing a significant less amount of affect than the other two groups. These findings are consistent with previous research and are the first to suggest that even at a young age, individuals with the mUPD subtype perform more similarly to children with ASD than the DEL subtype, potentially indicating a higher overlap in symptomatology and risk for ASD in the mUPD population (Dimitropoulos et al. 2013; Hogart et al. 2010).

When comparing functioning on behavioral assessment to parent report, another interesting pattern emerges. Results from the pretend play task show that the DEL and mUPD subtypes significantly differed from one another on a number of domains, with the mUPD group showing fewer aggressive interpersonal acts (an indicator of more complexity in play) and affect frequency in play. Further, on some measures, such as organization of a storyline and time spent in symbolic play, the mUPD subtype did not differ from the ASD group and both evidenced significantly lower ability in these domains as compared to the DEL subtype. This again suggests that children expressing the mUPD subtype may evidence more significant deficits in social cognitive functioning, even at this early age. These findings are important given that previous research has shown that pretend play constructs such as organization, symbolic play ability, and affect expression are related to prosocial behavior (Fehr and Russ 2013) social competence (Kaugars and Russ 2009) and emotional understanding and regulation (Seja and Russ 1999; Hoffmann and Russ 2012). Recognizing differences in pretend play ability provides an avenue for intervention to not only bolster areas of pretend play but also enhance other skill sets important to early social cognitive development.

In contrast, when examining parent report findings, there was no difference in functioning by PWS subtype. While the DEL group appeared to score higher than the mUPD group on the SSIS and SCQ, these differences were not significant. In some instances, the DEL and ASD groups differed on level of functioning in domains such as social communication, cooperation, assertiveness, and engagement. On other measures, such as responsibility, empathy, and self-control, the ASD group scored significantly lower than both the DEL and mUPD groups. This suggests that, in the current study, parents are perceiving social cognitive difficulties regardless of PWS subtype that are not as severe as children with ASD. This difference in behavioral assessment versus parent report is an important one. The majority of research in PWS has focused on parent observations, which provide only a part of the picture. However, findings from this study suggest that parent report alone may not be nuanced enough to capture the specific differences between PWS subtypes. Along these lines, Dykens et al. (2017) and Bennett et al. (2017) found that parent report overgeneralized deficits evident in children with PWS when evaluating a child for an autism diagnosis. Clinical observation and assessment provided a more accurate picture of autism symptomology and severity. Taken together, findings from previous research and the current study point to the need of behavioral observation when assessing social cognitive ability. The ability to use more comprehensive measures of child functioning has significant implications for early intervention efforts that may need to be individually tailored to each child’s ability.

It is also important to note that although the mUPD and ASD groups had lower quality of pretend play as compared to the DEL group, in some instances, the two groups also differed from one another. For example, the ASD group spent significantly more time in functional play and expressed less divergent themes and substitution frequency during the play task than the mUPD group. These findings are consistent with previous research, which suggests that children with ASD do not necessarily present with deficits in functional play ability but rather have significant impairments in being able to engage in higher level symbolic play, such as expressing divergent storylines in their play or using toys “as if” they were something else (i.e. substitutions) (Lam and Yeung 2012; Jarrold 2003). Further, as can be seen by parent report on the SCQ, the mUPD group mean score fell below the cut-off score for an autism diagnosis. Interestingly, the mUPD subtype was the only group to show significant correlations between the SCQ and pretend play measures, perhaps suggesting the larger variability in this group corresponds with challenges on these social measures for some children. This should be investigated further with a larger sample. However, SSIS findings also indicate that children with the mUPD subtype also displayed functioning that was significantly higher than the ASD group in some instances as reported above. These findings suggest that the mUPD subtype may be evidencing more significant difficulties in social cognitive ability at this early age range in comparison to the DEL subtype, but that these difficulties are (1) unique from and (2) not as severe as preschoolers with ASD. Overall, these findings may suggest that children with the mUPD subtype have differing needs than children with the DEL subtype. This is important for clinicians and parents to be aware of so that proper assessment and intervention techniques are implemented and tailored to these expressed differences.

Social Cognition & Other Domains of Development

The current findings also suggest unique relationships between receptive language, autism severity, and social skills with pretend play across the three groups. Language ability is an important factor to take into account when assessing young children with developmental disabilities and in disorders known to have co-occurring language difficulties, such as PWS and ASD (Dimitropoulos et al. 2013; Hudry et al. 2010). It is important to understand how language ability may relate to domains being measured and impact differences in functioning evidenced across these groups. Previous research in ASD has shown that preschoolers present with more severe deficits in receptive rather than expressive language and that there is a relationship between language development and social cognitive ability (Hudry et al. 2010). Specifically, research has shown that early social skills, such as joint attention predict later language development (Mundy et al. 1990). Psychophysiological work in ASD has also shown that individuals with high social cognition often present with higher receptive language ability (Patriquin et al. 2013). Although directionality of this relationship is still being delineated, it provides evidence of an important link between these two developmental domains in children with autism. In PWS, less research has been conducted, however, findings suggest that the DEL subtype may present with more expressive than receptive language difficulties, whereas the mUPD subtype exhibits a discrepancy more similar to autism with higher expressive versus receptive language abilities (Dimitropoulos et al. 2013). This same research also found no association between language and adaptive behavior in children with PWS yet no study has examined how domains of language may relate to early social cognitive ability in this population (Dimitropoulos et al. 2013). In the current study, receptive language ability did not differ across the three groups, yet the relationships between receptive language and APS-P performance did vary, with the ASD group evidencing the most significant correlations between these two domains. Further, the ASD group also evidenced the most correlations between social skills and play ability. This may be an important factor to consider in understanding the social cognitive phenotype of ASD in comparison to the mUPD or DEL groups. Specifically, there may be a unique relationship between these constructs in children with ASD that differs from those with PWS, which could prove important in tailoring intervention to these different populations.

Relatedly, within PWS subtypes, the mUPD group had more correlations that reached significance between measures of autism severity, social skills, and pretend play ability than the DEL group. These findings may relate to the higher variability of functioning and ASD symptomatology evident in this group. Within the DEL subtype, autism severity and social functioning were not related, which was more consistent with the TD norm reference group, perhaps suggesting a more similar pattern of relationships between domains of functioning across these two groups—something that was similarly observed on both behavioral tasks and parent report in the current study. Taken together, these results indicate that multiple areas may impact the development of social cognitive ability. Findings from this study suggest that future research should continue to characterize other aspects of functioning, such as language, symptom severity, and socioemotional functioning, in understanding the role they may play in how social cognitive deficits are conceptualized and treated in these different populations.

Limitations

While this study has important implications for the PWS population, several limitations should be noted. First, the current study is limited by its sample size. The small sample size had the potential to decrease power in the current study, could have increased the likelihood of Type I and II errors in the results, and restricted the ability to use multivariate tests. However, given the low prevalence rate of PWS within the general population, the number of participants reported in the current study match what has been reported on the literature previously. A second limitation is the cross-sectional design utilized in this study. Future work should aim to follow children with PWS across the preschool and early childhood period to better understand the trajectory of potential social cognitive deficits and their relationship with other areas of functioning through the use of behavioral assessment in combination with parent report. A third limitation is the use of the APS-P in 3 year-old children. Although previous studies have administered and scored the measure using children as young as 3 years of age and our current findings suggest no difference in how the various ages performed on the task and what variables of interest the play constructs related to, there is still the need to validate the task in younger samples, which has not been done up to this point and may have impacted the findings. In addition, portions of the APS-P have not yet been validated. Further validation of the seven additional APS-P variables used in the current study is warranted. However, inter-rater reliability was as high on the new variables as original APS-P variables and correlations between new and original variables and other constructs of interest (i.e. social skills, empathy, cooperation on the SSIS; negatively with severity scores on the SCQ) were found.

Conclusion

Outside of these limitations, the current study is the first to show that preschoolers with PWS evidence deficits in social cognitive ability that are not purely accounted for by cognitive delays. Findings also suggest that the severity of these deficits and the difference between subtype functioning varies as a function of either parent report or behavioral assessment. Parents of children with both PWS subtypes are more likely to report deficits across social cognitive domains whereas behavioral assessment shows a more complex and disparate picture of functioning between the DEL and mUPD groups. Specifically, in the current study, children with the mUPD subtype evidenced more similarities to the ASD group for some characteristics. Conversely, children with the DEL subtype presented with higher levels of functioning, more similar to the TD group. These findings are extremely important in that they provide initial evidence that (1) decreased social cognitive ability is evident early in development in children with PWS, (2) these deficits differ by subtype and (3) these differences may be important in informing early intervention techniques so as to be more specifically tailored to each subtype’s ability level and needs.

References

Bennett, J., Hodgetts, S., Mackenzie, M., Haqq, A., & Zwaigenbaum, L. (2017). Investigating autism-related symptoms in children with Prader-Willi syndrome: A case study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(3), 517.

Bishop, S. L., Guthrie, W., Coffing, M., & Lord, C. (2011). Convergent validity of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning and the differential ability scales in children with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116(5), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-116.5.331.

Blumberg, S. J., Bramlett, M. D., Kogan, M. D., Schieve, L. A., Jones, J. R., & Lu, M. C. (2013). Changes in prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder in school-aged US children: 2007 to 2011–2012. National Center for Health Statistics Reports. Number 65. National Center for Health Statistics.

Choudhury, S., Blakemore, S. J., & Charman, T. (2006). Social cognitive development during adolescence. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 1(3), 165–174.

Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284.

Dawson, G., Toth, K., Abbott, R., Osterling, J., Munson, J., Estes, A., et al. (2004). Early social attention impairments in autism: social orienting, joint attention, and attention to distress. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 271.

Dimitropoulos, A., Ferranti, A., & Lemler, M. (2013a). Expressive and receptive language in Prader-Willi syndrome: Report on genetic subtype differences. Journal of Communication Disorders, 46(2), 193–201.

Dimitropoulos, A., Ho, A., & Feldman, B. (2013b). Social responsiveness and competence in Prader-Willi syndrome: Direct comparison to autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(1), 103–113.

Dimitropoulos, A., & Schultz, R. T. (2007). Autistic-like symptomatology in Prader-Willi syndrome: A review of recent findings. Current Psychiatry Reports, 9(2), 159–164.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). PPVT-4: Peabody picture vocabulary test. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessments.

Dykens, E. M., Roof, E., Hunt-Hawkins, H., Dankner, N., Lee, E. B., Shivers, C. M., et al. (2017). Diagnoses and characteristics of autism spectrum disorders in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 9(1), 18.

Fehr, K. K., & Russ, S. W. (2013). Aggression in pretend play and aggressive behavior in the classroom. Early Education & Development, 24(3), 332–345.

Fehr, K. K., & Russ, S. W. (2016). Pretend play and creativity in preschool-age children: Associations and brief intervention. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 10(3), 296.

Geschwind, D. H., & Levitt, P. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders: Developmental disconnection syndromes. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 17(1), 103–111.

Gray, D. E. (2006). Coping over time: The parents of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 970–976.

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2008). Social skills improvement system: Rating scales manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson.

Higgins, D. J., Bailey, S. R., & Pearce, J. C. (2005). Factors associated with functioning style and coping strategies of families with a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 9(2), 125–137.

Hobson, R. P., & Lee, A. (1999). Imitation and identification in autism. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40(4), 649–659.

Hoffmann, J., & Russ, S. (2012). Pretend play, creativity, and emotion regulation in children. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6(2), 175.

Hogart, A., Wu, D., LaSalle, J. M., & Schanen, N. C. (2010). The comorbidity of autism with the genomic disorders of chromosome 15q11. 2-q13. Neurobiology of Disease, 38(2), 181–191.

Hudry, K., Leadbitter, K., Temple, K., Slonims, V., McConachie, H., Aldred, C., et al. (2010). Preschoolers with autism show greater impairment in receptive compared with expressive language abilities. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45(6), 681–690.

Jarrold, C. (2003). A review of research into pretend play in autism. Autism, 7(4), 379–390.

Kaugars, A. S., & Russ, S. W. (2009). Assessing preschool children’s pretend play: Preliminary validation of the affect in play scale-preschool version. Early Education and Development, 20(5), 733–755.

Lam, Y. G., & Yeung, S. S. S. (2012). Cognitive deficits and symbolic play in preschoolers with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 560–564.

Marcelo, A. K., & Yates, T. M. (2014). Prospective relations among preschoolers’ play, copying, and adjustment as moderated by stressful events. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.01.001.

Mullen, E. M. (1995). Mullen scales of early learning (pp. 58–64). Circle Pines, MN: AGS.

Mundy, P., Sigman, M., & Kasari, C. (1990). A longitudinal study of joint attention and language development in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20(1), 115–128.

Nurmi, E. L., Dowd, M., Tadevosyan-Leyfer, O., Haines, J. L., Folstein, S. E., & Sutcliffe, J. S. (2003). Exploratory subsetting of autism families based on savant skills improves evidence of genetic linkage to 15q11-q13. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(7), 856–863.

Olson, K. R., & Dweck, C. S. (2008). A blueprint for social cognitive development. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(3), 193–202.

Patriquin, M. A., Scarpa, A., Friedman, B. H., & Porges, S. W. (2013). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: A marker for positive social functioning and receptive language skills in children with autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Psychobiology, 55(2), 101–112.

Russ, S. W., & Association, American Psychological. (2014). Pretend play in childhood: Foundation of adult creativity (pp. 45–62). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Rutter, M., Bailey, A., & Lord, C. (2003). SCQ. The social communication questionnaire. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Rydell, A. M., Hagekull, B., & Bohlin, G. (1997). Measurement of two social competence aspects in middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 33(5), 824.

Seja, A. L., & Russ, S. W. (1999). Children’s fantasy play and emotional understanding. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 28(2), 269–277.

Senju, A. (2013). Atypical development of spontaneous social cognition in autism spectrum disorders. Brain and Development, 35(2), 96–101.

Sparrow, S. S., Balla, D. A., & Cicchetti, D. V. (2005). Vineland II: Vineland adaptive behavior scales. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Tager-Flusberg, H., & Sullivan, K. (2000). A componential view of theory of mind: Evidence from Williams syndrome. Cognition, 76(1), 59–90.

White, S. W., Keonig, K., & Scahill, L. (2007). Social skills development in children with autism spectrum disorders: A review of the intervention research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(10), 1858–1868.

Yates, T. M., & Marcelo, A. K. (2014). Through race-colored glasses: Preschoolers’ pretend play and teachers’ ratings of preschooler adjustment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(1), 1–11.

Zyga, O., Russ, S., Ievers-Landis, C. E., & Dimitropoulos, A. (2015). Assessment of pretend play in Prader-Willi syndrome: A direct comparison to autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(4), 975–987.

Acknowledgments

This research would not be possible without the financial support of The Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (FPWR) and the Mt. Sinai Catalytic Award through the International Center for Autism Research and Education (ICARE). Further we would like to thank lab members Ellen Doernberg and Brooke Bailey for their time and efforts in data collection and coding. Lastly, we deeply thank all of the families who participated in this research program.

Funding

This study was funded by the Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (FPWR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD concieved of the study, and together with OZ and SWR developed the design of the study. OZ assisted in the coordination of the study, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the initial manuscript. All authors interpreted the data, made revisions, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Case Western Reserve University Institutional Review Board (IRB-2015-1240) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.”

Informed Consent

“Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.”

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dimitropoulos, A., Zyga, O. & Russ, S.W. Early Social Cognitive Ability in Preschoolers with Prader–Willi Syndrome and Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 49, 4441–4454 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04152-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04152-4