Abstract

We examined the relationship between initial parenting stress and change in parental responsivity for 56 culturally and socioeconomically diverse families in a 12 week randomized control trial of Pathways Early ASD Intervention. Families were randomized into the Pathways (n = 32) or treatment-as-usual (TAU n = 24) group. Overall, Pathways parents experienced decreased stress, while TAU parents experienced an increase. The relationship between initial parental stress and change in parent responsivity was moderated by group membership. Pathways parents became more responsive but responsivity was not influenced by initial parental stress. In contrast, responsivity was negatively affected by initial parenting stress in the TAU group. Results are discussed in terms of components of a parent-mediated ASD intervention that may reduce parental stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder that severely compromises the development of social relatedness, reciprocity, and social communication. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Baio et al. 2018) has estimated that 1 in 59 children are on the autism spectrum, with males diagnosed four times more often than are females. Parents of children with ASD often have high levels of parenting stress, especially around the time of their child’s diagnosis (Elder et al. 2017; Zaidman-Zait et al. 2017). High parenting stress has a negative influence on families (Morris et al. 2017) and is known to mitigate parenting behaviors that affect nurturing parent–child relationships (Abidin 2012; Davis and Carter 2008).

Understanding the relationship between parenting stress and parenting behaviors is crucial because parenting stress can reduce the effectiveness of an intervention (Osborne et al. 2008; Stadnick et al. 2015; Watson et al. 2017). This is particularly important for families who have toddlers with ASD, for which best practice involves parents’ being coached to incorporate specific behavioral and developmental strategies into daily routines and family activities (Schreibman et al. 2015; Zwaigenbaum et al. 2015). The purpose of this study is to explore the impact of Pathways parent-mediated early ASD interventions (Campbell and Hoffman 2012) on parental stress and parenting behaviors in culturally and socioeconomically diverse families around the time of diagnosis. Pathways is a manualized parent-mediated, naturalistic developmental behavioral intervention (NDBI) for toddlers with ASD that fits the service delivery model of most state IDEA Part C programs.

Parenting Stress

Parenting stress refers to stress in the parent–child relationship that is derived from parents’ perceptions of their child’s temperament and behaviors, in concert with parents’ perception of the quality of their interactions with their child (Abidin 2012). Parents of children with ASD tend to experience higher parenting stress as compared with parents of typically developing children and parents of children with other developmental disorders (Baker-Ericzén et al. 2005; Estes et al. 2013; Hayes and Watson 2013; Porter and Loveland 2018; Wolf et al. 1989).

Parenting stress in parents of children with ASD has been associated with the child’s problem behaviors (Estes et al. 2013; Kasari and Sigman 1997; Zaidman-Zait et al. 2014) and the child’s difficulties with reciprocal social interactions and prosocial behaviors (Baker-Ericzén et al. 2005; Davis and Carter 2008; Kasari and Sigman 1997). Davis and Carter analyzed the contributions of ASD symptoms, child problem behaviors and competencies, child cognitive functioning, and parental affective symptoms on parenting stress in parents of young children with ASD around the time of diagnosis. They found that deficits in the child’s social skills were the most consistent predictors of parenting stress. In addition, they found that the most stressful area of parenting for mothers was related to the difficulties in the child’s social reciprocity or relatedness. Other studies have found that parents’ stress was related to a lack of social support (Da Paz and Wallander 2017; Porter and Loveland 2018; Zaidman-Zait et al. 2017) or the use of ineffective or disengaged coping styles (Hastings 2002; Zaidman-Zait et al. 2017).

High stress in parents of children with ASD also has been linked to psychological distress and dysphoria and a higher risk of parental depressive symptoms (Costa et al. 2017; Estes et al. 2013; Wolf et al. 1989). The latter has further been associated with lower parental involvement and decreased interactions with the child (Schiltz et al. 2018). For example, Kasari and Sigman (1997) found that parents of young children with ASD who had higher levels of stress perceived their child as more difficult and spent less time engaged with their child during observed parent–child interactions. This may be even more problematic for families in lower socioeconomic strata, for whom a scarcity of resources exacerbates inappropriate parenting behaviors that, in turn, predict negative child behaviors (Trentacosta et al. 2018).

Parental Behavior

Parent-mediated interventions provide an ideal means to support parents of toddlers who are newly diagnosed with or suspected of having ASD by coaching the parents to engage in positive interactional strategies. This is particularly helpful because parents of children with ASD tend to be more controlling or directive with their children as compared with parents of typically developing children (Kasari et al. 1988; Kim and Mahoney 2004). Many parent-mediated interventions coach parents to be more responsive to their toddler with ASD because parental responsivity is predictive of subsequent gains in the child’s language abilities (Oono et al. 2013; Shire et al. 2016; Siller et al. 2013; Siller and Sigman 2008; Solomon et al. 2014).

Responsive interactions are those for which the parent’s verbal and nonverbal behaviors are contingent on the child’s focus of attention or communicative acts (Kasari et al. 2014; McDuffie and Yoder 2010; Rollins 2003; Rollins and Greenwald 2013). Such interactions also are referred to as “following in” to the child’s interests or initiations, as opposed to directing the child’s attention elsewhere or placing demands on the child (Carpenter et al. 1998). Parental responsiveness thus provides a referential framework in which the toddler may ground the parent’s social interaction and language input (Bruner 1983; Rollins 2003; Snow 1999). In contrast, directing the child’s attention to a new object or focus makes it difficult for the child to establish a joint attentional focus with his or her parent, thereby diminishing the social and language learning environment (Kasari et al. 2014; Rollins 2003; Snow 1999; Tomasello and Farrar 1986). Several parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with ASD have been shown to increase parental responsivity (McDuffie and Yoder 2010; Siller et al. 2013; Solomon et al. 2014). What is less known are the effects of perceived parental stress as related to the parent–child relationship in terms of enhancing responsive parental behaviors.

The goal of this study is twofold. The first goal is to evaluate the efficacy of Pathways Early ASD Intervention (Campbell and Hoffman 2012) on reducing parenting stress in culturally and socioeconomically diverse parents of toddlers with ASD around the time of diagnosis. The second goal is to identify whether Pathways parent-mediated early ASD intervention can ameliorate the negative effects that parenting stress has on parent–child interactions. Pathways is a parent-mediated NDBI for toddlers with ASD that coaches parents on how to engage their toddlers in early-developing social interactions that are core deficit areas for toddlers with ASD. Pathways was developed to meet the service delivery model of IDEA Part C programs in most states with the aim of increasing options for publicly funded ASD-specific toddler intervention. Pathways has been found to be effective for increasing toddlers’ early social skills (Rollins 2018; Rollins et al. 2016), which are precursors to joint attention (Adamson and Russell 1999; Greenspan and Shanker 2004; Rollins and Greenwald 2013). Two research questions guided this study:

-

1.

To what extent is Pathways’ autism-specific, parent-mediated intervention effective in lessening the effects of parental stress?

-

2.

To what extent is Pathways’ autism-specific, parent-mediated intervention effective in lessening the effects of initial parental stress on parents’ developing a more responsive interactional style with their toddler?

We hypothesize that the parent-mediated ASD-specific intervention for toddlers with ASD will be more effective in alleviating parental stress than will a treatment-as-usual (TAU) comparison group that was enrolled predominantly in IDEA Part C early intervention programs. In addition, we hypothesize that, adjusting for initial parental stress, parents enrolled in the Pathways intervention will show more change in developing a responsive interactional style with their toddler than will parents in the TAU group.

Methods

Participants

This study is part of a larger randomized control trial to evaluate the efficacy of Pathways Early ASD Intervention as compared to a communication group and a TAU group (Rollins 2018). The communication group intervention was similar to that of Pathways, except it targeted early communication skills (as opposed to early social skills). In the full study, a total of 110 toddlers with suspected or confirmed ASD were evaluated for eligibility; 110 children and families met the criteria, and 92 were randomized into one of three conditions, with 13 children who were dropped from the study following randomization (Fig. 1).

There were no significant differences in the background variables between the children who remained in the Pathways and TAU groups and those who were dropped from the study. Comparisons between the Pathways and the early communication groups were used to understand the effectiveness of the social eye gaze protocol on intervention success, while comparisons between the Pathway and TAU groups were used to understand the effectiveness of the Pathways program. Data from the communication group will not be discussed here. Rather, the current study compares data from the Pathways (n = 32) and the TAU control (n = 24) groups.

Participants were recruited for the larger study through local infant–toddler programs, community centers, advocacy groups, physicians’ offices, social media, and word of mouth. Eligibility criteria included (a) having a chronological age less than 36 months at the start of the study; (b) receiving an autism classification on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al. 2012), administered by a research reliable clinician; (c) having no other medical, neurological, or genetic concerns or disorders; and (d) having the primary home language be English or Spanish.

At intake, toddlers who were later randomized to the Pathways group received an average of 1.38 h/week of intervention (SD = 0.95, range 0–3.13), while toddlers later randomized to the TAU group received an average of 1.92 h/week (SD = 2.17, range 0–9). Independent samples t-tests revealed no significant differences in hours of intervention between the Pathways and TAU groups (t(54) = − 1.05, p = .30 d = . 27), indicating that there was a small effect size. Although the majority of toddlers in both groups were receiving early childhood intervention (ECI) services, proportionately more children who were later randomized to the Pathways group received no intervention at intake (16% in Pathway and 8% in TAU) and fewer hours, on average, of private/community service at intake (Table 1). Families randomized into the Pathways group had to be willing to suspend other speech, developmental, or applied behavior analysis (ABA) services for the duration of the study. All caregivers agreed to participate in the study, using an informed consent procedure approved by the university’s Internal Review Board. There was no cost for participating in the study.

Study Design

The principal investigator used a computer-generated list of random numbers to allocate participants to treatment conditions. Sealed envelopes were used for allocation concealment and were opened after all pre-intervention assessments were completed. Therefore, study clinicians were blind to group assignment pre-intervention but not post-intervention. Post-intervention testing was conducted by clinicians who were not familiar with the target toddler and family. All assessments were administered in the family’s home or at a convenient location within 2 weeks of the start and stop of intervention. Recruiting, intake, and pre- and post-intervention testing procedures were identical for both conditions. For the Pathways group, interventionists made home visits and coached parents on key components of early social interactions (Fig. 2). The TAU control group received an intervention from community early-intervention providers. Families in the TAU control group could elect to receive Pathways services at no charge when they completed the study.

Clinician Qualifications and Training

Four clinicians participated in the study. Three had a master’s degree and were certified speech-language pathologists. The fourth had a bachelor’s degree in education and 15 years of experience as an early interventionist. Two of the speech pathologists were bilingual (English–Spanish) and, when requested, provided assessments and interventions in Spanish.

Assessment Training

All assessments used in the study were within the study clinician’s professional scope of practice. Nonetheless, study clinicians were trained on all assessment protocols. Specifically, prior to data collection, study clinicians reviewed administration and scoring procedures for all standardized test with a licensed psychologist, who was research reliable on the ADOS-2, and administered standardized testing with practiced children until they were 90% reliable with an expert clinician on administration and scoring procedures for all standardized assessments. Further, during the study, two clinicians were always present for each assessment. One clinician administered a test, while the second assisted. The two clinician scored the assessments together.

Intervention Training

Clinicians were trained to ensure fidelity of implementation of intervention procedures prior to seeing study participants. The training took approximately 6 weeks. Each clinician independently studied the manual prior to participating in the review and role-play sessions with an expert clinician. Then, each clinician was coached by an expert clinician while providing interventions to practice families not included in the study. During the course of the study, clinicians also participated in a weekly supervision session with the first author, in which they viewed videotapes of intervention sessions.

Pathways Intervention Procedures

Pathways is a targeted, manualized program (Campbell and Hoffman 2012) with English and Spanish versions of the written and audiotaped manuals. Study clinicians made weekly visits to the child’s home and worked with the caregiver for 1½ h, as schedules permitted. To promote naturalistic interactions, parents used toys that were present in the home. The clinicians provided the parents with oral information and reviewed the relevant unit in the program manual (Appendix A). The manual contains information about the program and a curriculum that uses explicit instructions and suggested activities.

The clinician presented each unit in sequence, starting with Unit 1, and moved successively to the next unit when readiness to move on was demonstrated. Readiness was jointly determined by the clinician and the parent when the parent had adhered to all treatment strategies on the fidelity checklist for the specified unit and all previous units (Appendix A). Consequently, some units were presented only one time, while other units were presented over two or more sessions, according to the parent’s abilities. It is noteworthy that, because the intervention was developed to coach parents, the strategies are cumulative, and each new strategy builds on previous strategies that the caregiver has learned. As such, the intervention assumes no prior knowledge on the part of the adult who is implementing the intervention and provides for the addition of interactional strategies slowly. For example, the protocol for mutual eye gaze was introduced to the Pathways participants in Unit 3, but caregivers continued to work on the eye gaze protocol as other strategies were added. This helps to ensure that the adult masters basic interactional strategies before adding other components.

Each week, the interventionist rated the parent’s adherence to treatment strategies, using a four-point Likert scale (Appendix A). Because the program is cumulative, the parent was rated on new objectives from the current unit as well as on all previous objectives. Overall, parents’ adherence to treatment objectives ranged from 86 to 100% (M = 96%, SD = .04).

Treatment-As-Usual Group

The TAU group received an average of 6.65 h (SD = 8.90) of therapy per week with a range of 1–28 h/week. Thirteen of the 24 children were enrolled in a state-sponsored local ECI program and received all of their services from that agency (M = 1.69, SD = .79 h/week). Six children supplemented their state services with a speech language service and ABA services M = 15.58, SD = 10.74 h/week). Finally, five children received all of their services in private or as part of other community-based services (M = 7.9, SD = 9.88 h/week).

Video Data Collection and Coding Procedures

All caregiver-child dyads were digitally recorded for 10 min, using an iPad 2 for a wide-angle recording of the interaction (Video Stream 1), and with hidden-camera eyeglasses worn by the parent to capture the child’s eye contact (Video Stream 2) at intake prior to randomization and post-intervention. Parents were instructed to play with their child as they typically do. The interventionists gave the parents instructions on where to place the hidden-camera glasses to assist with data collection but made no suggestions or recommendations about the interactional strategies.

For each recording, the two streams of digitized videos (i.e., iPad and glasses) were segmented into 2 s intervals and time-linked, using the conventions of the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES; MacWhinney 1991). This allowed for partial interval coding of parental responsivity. The use of 2 s intervals allowed for coding of parent responses within an optimal time window following a behavior (McGillion et al. 2013).

All coders received a multimedia coding manual with definitions and examples of coding categories. Coders were trained by first reviewing a set of coded practice videos, followed by coding a second set of videos with the codes hidden, until they achieved substantial inter-rater agreement, measured by obtaining a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of .80 or above. Cohen’s kappa, which considers chance agreement between coders, is a more robust measure than is percent agreement because it takes into account the agreement that occurs by chance alone. In addition, all coders recalibrated their reliability every 3 months. All coders were blind to group assignment and time (i.e., pre- or post-intervention).

Measures

ASD Classification

The ADOS-2 (Lord et al. 2012) was used to confirm a research diagnosis of ASD at intake prior to randomization. The ADOS-2 is a semi-structured evaluation of communication, social interaction, play, and restricted/repetitive behaviors for children who are suspected of having ASD. The ADOS-2 is available in five versions (modules) that are selected based on the child’s age and expressive language level. For the present study, the Toddler Module, which is intended for toddlers 12–30 months of age, was administered to 29 toddlers, later randomized into the Pathways group, and 19 toddlers, later randomized into the TAU group. Module 1 of the ADOS-2, which is intended for children aged 31 months and older whose language abilities range from no speech to simple phrases, was administered to the three toddlers randomized into the Pathways group and five randomized into the TAU group.

Verbal and Nonverbal IQ

The Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; Mullen 1995) was used to estimate verbal and nonverbal IQ scores at intake prior to randomization. The MSEL is a standardized, direct assessment of development for young children (ages 0–68 months) that yields age equivalency scores for gross and fine motor skills, visual reception, and receptive and expressive language. Using the procedure outlined in Bishop et al. (2011), we used MSEL age-equivalency scores for fine motor skills and visual reception to estimate nonverbal IQ scores, whereas the age equivalency scores for receptive and expressive language were used to estimate Verbal IQ scores.

Social and Communication Skills

The parent interview form of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (VABS-II; Sparrow et al. 2005) was administered at intake prior to randomization and at post-intervention to measure social and communication skills. The VABS-II is a standardized test of adaptive functioning for individuals from birth to age 90 months. The test yields an adaptive behavior composite score and domain scores for communication, daily living, socialization, and motor development and has good test–retest reliability (.88–.92).

Parenting Stress

The Parenting Stress Index-4 (PSI-4-SF; Abidin 2012) was administered at intake, prior to randomization, and at post-intervention to assess (a) overall parental stress, which is an indicator of risk for dysfunctional parenting (Total Stress), and stress from parent–child dysfunctional interactions (PCDI). The PSI-4-SF is a standardized parent questionnaire on which parents rate agreement on 36 items using a five-point Likert scale. Total Stress and PCDI are expressed as percentile scores, for which higher scores indicate higher levels of stress. Scores in the 85th to 89th percentiles are considered indicative of being highly stressed, and scores in the 90th to 100th percentiles indicate clinical levels of stress.

Parental Responsivity

Parental responsivity was coded from 10-min videos of caregiver-child interaction. The videos were collected at intake, prior to randomization, and at post-intervention. The parental responsivity coding system was adapted from Kasari et al. (2014) and captured how the parent responded to his or her child’s verbal or nonverbal communication acts and attentional focus. Specifically, for each 2 s interval, the parent was coded as responsive, directive, onlooking, or ignoring, based on how the parent was interacting with the child. Parental responsivity was measured as the number of 2 s intervals in which the parent was coded as responsive. All coders were blind to group assignment and time (i.e., intake- or post-intervention). Two coders independently coded 20% of the baseline and 20% of the post-intervention computer files chosen at random. Inter-rater reliability, expressed as Cohen’s kappa, was M = .81, SD = .46 for baseline videos and M = .81, SD = .45 for post-intervention videos. These kappa statistics are substantial and indicate near-perfect agreement (Landis and Koch 1977).

Time-Controlled Residual Change Measures

Time-controlled residual change variables were used to measures changes from pre intervention-to-post intervention for Total Stress, PCDI, and parental responsivity. Time-controlled residual change measures were used to adjust for regression toward the mean effects. Each time-controlled residual change variable is comprised of the residual scores (i.e., actual minus predicted values) from a regression model of the measure of interest (i.e., total stress) post-intervention on the same measure at baseline. As such, a time-controlled variable accounts for all of the variance in a measure, post-intervention, that cannot be attributed to the measure at baseline. Because time-controlled variables are derived from a regression model, a participant’s score of 0 indicates that the participant’s score post-intervention was the same as the participant’s score at baseline. Conversely, positive values indicate that a participant’s scores were higher post-intervention than at baseline, and a negative value indicates that a participant’s scores were lower post-intervention than at baseline. All assumptions of regression were analyzed and no model violations were present.

Results

Independent t tests revealed that there were no group differences on background variables at baseline (Table 2). There was, however, a medium effect size associated with age and a small effect associated with maternal education and nonverbal IQ. Toddlers came from culturally and socioeconomically diverse families (Table 3). Noteworthy is the low percentage of Caucasian families and high percentage of Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)/Medicaid eligible families (47% of those enrolled in Pathways and 46% in TAU).

Correlational analyses reveal that none of the background variables was related to time-controlled Total Stress and PCDI; however, nonverbal IQ was correlated with the time-controlled parental responsivity measure (Table 4). Following the principle of parsimony, only nonverbal IQ was retained for use in the regression analyses for which time-controlled parental responsivity was the outcome.

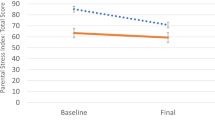

Effects of Intervention on Parental Stress

At baseline, the percentage of parents in the Pathways group who reported scores above 85 (i.e., high or clinically significant range) for Total Stress and PCDI was 31 and 34, respectively. Similarly, at baseline, the percentage of parents in the TAU group who reported Total Stress and PCDI above 85 was 25 and 42, respectively. An independent-samples t test revealed a mean difference of 12.2 percentile points (CI = 4.15, 20.2) for time-controlled total stress, t(44.4) = 3.06, p = .00 (two-tailed), d = .79. On average, Total Stress decreased for Pathways parents (M = − 5.08, SD = 20.1), while it increased in the TAU group (M = 7.07, SD = 8.49). A mean difference of 9.92 percentile points (CI = 1.56, 18.3) was found for time-controlled PCDI, t(49.7), p = .02 (two-tailed), d = .62. On average, PCDI decreased for the Pathways parents (M = − 4.15, SD = 19.9) and increased in the TAU group (M = 5.77, SD = 10.7).

Effects of Initial Stress and Intervention on Parental Responsivity

Hierarchical regression models were used to analyze the effects of Total Stress and PCDI on time-controlled parental responsivity (Tables 5, 6). All assumptions of regression were analyzed, and no model violations were present.

Total Stress

We found that adjusting for nonverbal IQ resulted in a statistically significant interaction between initial Total Stress percentile score and group (Model 4, Table 5), indicating that the magnitude of the effect of initial Total Stress on parental responsivity was moderated by group membership. The interaction term accounted for 8% of the variation in time-controlled parental responsivity (ΔR2 = .08, partial F = 7.07, p < .01) with the full model’s accounting for 44% of the variability in parent’s changes in responsivity from baseline to post-intervention. By probing the interaction (Fig. 3), we found that the conditional effect of Total Stress was significant for the TAU group (b1 = − 1.11, t(51) = − 3.62, p = .00) but not for the Pathways group (b1 + b3 = − .14, t(51) = − .74, p = .47), indicating that, on average, initial Total Stress had no relationship with change in parental responsivity for the Pathways group, whereas it had a steep negative effect on change in parental responsivity in the TAU group.

PCDI

The results for PCDI were similar (Model 4, Table 6), indicating that the magnitude of the effect of Initial Stress due to parent child dysfunctional interaction on parental responsivity was moderated by group membership. The interaction term accounted for 6% (ΔR2 = .06, partial F = 5.50, p < .02), with the full model’s accounting for 44% of the variability that contributed to a parent’s changes in responsivity from baseline to post-intervention. By probing the interaction (Fig. 4), we found that the conditional effect on PCDI was significant for the TAU group (b1 = − 1.05, t(51) = − 3.50, p = .00) but not for the Pathways group (b1 + b3 = − .17, t(51) = − 7.41, p = .46).

Discussion

The present study examined the effects of Pathways parent-mediated NDBI for toddlers with ASD on parent stress and parental responsivity as compared with that of a TAU control group. Pathways is a manualized intervention that was developed to fit the service delivery model and principles of many states’ IDEA Part C-funded ECI programs. As such, the program was family-centered. Interventionists coached parents to use evidence-based strategies with their toddlers on the autism spectrum while engaging them in daily activities and routines. In keeping with the ECI model in most states, we delivered the service in an authentic environment, and the intensity, in terms of the number and length of visits, was limited (i.e., 1.5 h per week). Pathways early autism intervention focused on core features of ASD, and parents were coached on face-to-face interactions that targeted mutual gazing, social engagement, and vocal-verbal reciprocity, which are the early emerging social precursors to joint attention (Adamson and Russell 1999; Greenspan and Shanker 2004; Rollins and Greenwald 2013). It is noteworthy that the families who participated in this study were from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, which increased the generalizability of this study. Most studies that evaluate the efficacy of early autism intervention programs draw from a homogeneous group of Caucasian, non-Hispanic families (Zwaigenbaum et al. 2015). In contrast, approximately one-third of our sample came from bilingual or monolingual Spanish-speaking families, many of whom were Medicaid- or CHIP-eligible, which means that they qualify for free or heavily subsidized healthcare.

Overall, the parents of toddlers with ASD in both groups had high baseline levels of Total Stress and stress related to PCDI, with about one-third of the parents’ having stress levels in the high or clinically significant range. The Pathways group experienced a decrease in Total Stress and in stress related to PCDI, while parents in the TAU group experienced an increase in stress for both measures over the 12-weeks intervention period. The mean difference of 12 percentile points for Total Stress and 10 percentile points for PCDI was statistically significant, and the effect size was large. These findings suggest that toddlers with ASD in the TAU group were at greater risk of having parents who exhibit poor parenting behaviors than were toddlers in the Pathways group.

This was corroborated in our regression analyses, in which we found that, when adjusting for nonverbal IQ, the relationship between initial parental stress (Total Stress and PCDI) and change in parental responsivity over the course of intervention was moderated by group membership. By probing the interaction, we found that, on average, change in parental responsivity over the 12-weeks intervention period was negatively affected by initial parenting stress (Total Stress and PCDI) for parents in the TAU group, whereas there was no effect of initial parenting stress for parents in the Pathways group. These findings are particularly impressive when one considers that many of our participants were from economically disadvantaged minority groups. In addition, other than nonverbal IQ, which had a small effect, we did not find other background variables, such as maternal education, toddler age, or autism severity, to be related to change in parental responsivity.

We speculate that there are several components of the Pathways program, an ASD-specific, parent-mediated intervention, that are critical to its effectiveness in terms of reducing parental stress and alleviating some of its negative effects. First, Pathways uses a parent-mediated coaching model that involves working with parents to teach strategies that are easily adopted in naturalistic environments. Other studies have found the coaching model to decrease parent stress (Estes et al. 2014; Koegel et al. 1996). Second, Pathways coaches parents on specific interactional strategies (e.g., face-to-face, social sensory routines, mutual gaze protocol) to facilitate social responsiveness and early social play, which are deficit areas that contribute to parental stress around the time of diagnosis (Davis and Carter 2008; Zaidman-Zait et al. 2017). Indeed, our pilot studies have found that Pathways is effective in facilitating early social development in toddlers with ASD (Rollins 2018; Rollins et al. 2016).

Third, Pathways provides a clear curriculum with multimodal teaching techniques (written and auditory versions of the manual, use of videotaped instructional methodology) and is individually paced for the parent. To avoid overwhelming the parent, the clinician presents each new targeted strategy in sequence only when the parent is ready to move on. Finally, the clinician supports the parents in terms of understanding social behaviors in toddlers with ASD, which has been found to reduce stress (Kasari et al. 2015). Although many of the parents who were in the TAU group were professionally supported, most were not engaged in a collaborative coaching model in which they were provided with information to further their understanding of ASD, and the support with which they were provided was related to vocabulary development rather than to early social skills. These findings highlight the need for ASD-specific interventions that focus on the core features of ASD early in life.

While clinicians were blind to group assignment at intake, a limitation of this study is that clinicians were not blinded when administering post-intervention assessments. To reduce bias, these assessments were conducted by a clinician who was not familiar with the family. In addition, the study did not attempt to measure parent perceptions of support related to the Pathways intervention. Future research could determine whether parent opinions support our speculation regarding the supportive nature of this intervention and whether parent perceptions of support are related to outcome measures. In addition, parental responsivity and parent stress measures were not collected several months after the conclusion of the intervention to assess maintenance. It may be that 12 weeks is too short a time for parents to maintain the interactional strategies taught in this study. Further, stress may be exacerbated as parents receive conflicting messages about intervention practices when returning to TAU programs. Understanding what happens to families as they return to TAU programs is an area for future research.

Despite these limitations, this study illustrates the efficacy of increasing positive parent behaviors while reducing parent stress for culturally and socioeconomically diverse families. The efficacy of Pathways among these socioeconomically and culturally diverse families in this study shows promise that Pathways could be implemented in IDEA Part C programs that serve disadvantaged families. An important next step is to replicate these findings with Part C providers in the context of their hectic job schedules. Effective early ASD community-based programs for disadvantaged families are crucial to help states to offer cost-effective models, build capacity for their early evidence-based interventions, and break down barriers to timely intervention.

References

Abidin, R. R. (2012). Parenting stress index, Fourth Edition (PSI-4). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Adamson, L. B., & Russell, C. L. (1999). Emotion regulation and the emergence of joint attention. In P. Rochat (Ed.), Early social cognition: Understanding others in the first months of life (pp. 281–297). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D. L., Maenner, M. J., Daniels, J., Warren, Z., … Dowling, N. F. (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(6), 1–23

Baker-Ericzén, M. J., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Stahmer, A. (2005). Stress levels and adaptability in parents of toddlers with and without autism spectrum disorders. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 30(4), 194–204.

Bishop, S. L., Guthrie, W., Coffing, M., & Lord, C. (2011). Convergent validity of the mullen scales of early learning and the differential ability scales in children with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116(5), 331–343.

Bruner, J. (1983). Child’s talk. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, M., & Hoffman, R. T. (2012). Pathways early autism intervention parent training manual. Bluff Dale, TX: Author.

Carpenter, M., Nagell, K., & Tomasello, M. (1998). Social cognition, joint attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 63(4), 1–6. (1–143).

Costa, A. P., Steffgen, G., & Ferring, D. (2017). Contributors to well-being and stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 37, 61–72.

Da Paz, N. S., & Wallander, J. L. (2017). Interventions that target improvements in mental health for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A narrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 1–14.

Davis, N. O., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1278–1291.

Elder, J. H., Kreider, C. M., Brasher, S. N., & Ansell, M. (2017). Clinical impact of early diagnosis of autism on the prognosis and parent-child relationships. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 283–292.

Estes, A., Olson, E., Sullivan, K., Greenson, J., Winter, J., Dawson, G., et al. (2013). Parenting-related stress and psychological distress in mothers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Brain and Development, 35(2), 133–138.

Estes, A., Vismara, L., Mercado, C., Fitzpatrick, A., Elder, L., Greenson, J., … Rogers, S. (2014). The impact of parent-delivered intervention on parents of very young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 353–365

Greenspan, S. I., & Shanker, S. (2004). The first idea: How symbols, language and intelligence evolved from our primate ancestors to modern humans. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Hastings, R. P. (2002). Parental stress and behaviour problems of children with developmental disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 27(3), 149–160.

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629–642.

Kasari, C., Gulsrud, A., Paparella, T., Hellemann, G., & Berry, K. (2015). Randomized comparative efficacy study of parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 554–563.

Kasari, C., & Sigman, M. (1997). Linking parental perceptions to interactions in young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 27(1), 39–57.

Kasari, C., Sigman, M., Mundy, P., & Yirmiya, N. (1988). Caregiver interactions with autistic children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 16(1), 45–56.

Kasari, C., Siller, M., Huynh, L. N., Shih, W., Swanson, M., Hellemann, G. S., et al. (2014). Randomized controlled trial of parental responsiveness intervention for toddlers at high risk for autism. Journal of Infant Behavior & Development, 37(4), 711–721.

Kim, G., & Mahoney, J. (2004). The effects of mother’s style of interaction on children’s engagement. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 24(1), 31–38.

Koegel, R. L., Bimbela, A., & Schreibman, L. (1996). Collateral effects of parent training on family interactions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 26(3), 347–359.

Landis, J., & Koch, G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.

Lord, C., Luyster, R., Gotham, K., & Guthrie, W. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

MacWhinney, B. (1991). The CHILDES project: Computational tools for analyzing talk. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

McDuffie, A., & Yoder, P. (2010). Types of parent verbal responsiveness that predict language in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 1026–1039.

McGillion, M. L., Herbert, J. S., Pine, J. M., Keren-Portnoy, T., Vihman, M. M., & Matthews, D. E. (2013). Supporting early vocabulary development: What sort of responsiveness matters? IEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Development, 5(3), 240–248.

Morris, A. S., Robinson, L. R., Hays-Grudo, J., Claussen, A. H., Hartwig, S. A., & Treat, A. E. (2017). Targeting parenting in early childhood: A public health approach to improve outcomes for children living in poverty. Child Development, 88(2), 388–397.

Mullen, E. M. (1995). Mullen scales of early learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Oono, I. P., Honey, E. J., & McConachie, H. (2013). Parent-mediated early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 8(6), 2380–2479.

Osborne, L. A., McHugh, L., Saunders, J., & Reed, P. (2008). Parenting stress reduces the effectiveness of early teaching interventions for autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(6), 1092–1103.

Porter, N., & Loveland, K. A. (2018). An integrative review of parenting stress in mothers of children with autism in Japan. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 66(3), 249–272.

Rollins, P. R. (2003). Caregivers’ contingent comments to 9-month-old infants: Relationships with later language. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24(2), 221–234.

Rollins, P. R. (2018). Setting the stage: Creating a social pragmatic environment for toddlers with ASD and their caregivers. Revista De Logopedia, Foniatria y Audiologia, 38(1), 14–23.

Rollins, P. R., Campbell, M., Hoffman, R. T., & Self, K. (2016). A community-based early intervention program for toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 20(2), 219–232.

Rollins, P. R., & Greenwald, L. C. (2013). Affect attunement during mother-infant interaction: How specific intensities predict the stability of infants’ joint attention. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 32(4), 339–366.

Schiltz, H. K., McVey, A. J., Magnus, B., Dolan, B. K., Willar, K. S., Pleiss, S., … Van Hecke, A. V. (2018). Examining the links between challenging behaviors in youth with ASD and parental stress, mental health, and involvement: Applying an adaptation of the family stress model to families of youth with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1169–1180

Schreibman, L., Dawson, G., Stahmer, A. C., Landa, R., Rogers, S. J., McGee, G. G., … Halladay, A. (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2411–2428

Shire, S. Y., Gulsrud, A., & Kasari, C. (2016). Increasing responsive parent-child interactions and joint engagement: Comparing the influence of parent-mediated intervention and parent psychoeducation. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders, 46(5), 1737–1747.

Siller, M., Hutman, T., & Sigman, M. (2013). A parent-mediated intervention to increase responsive parental behaviors and child communication in children with ASD: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 540–555.

Siller, M., & Sigman, M. (2008). Modeling longitudinal change in the language abilities of children with autism: Parent behaviors and child characteristics as predictors of change. Journal of Developmental Psychology, 44(6), 1691–1704.

Snow, C. E. (1999). Issues in the study of input: Fine tuning, universality, individual and developmental differences, and necessary causes. In P. Fletcher & B. MacWhinney (Eds.), The handbook of child language (pp. 179–193). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Solomon, R., Van Egeren, L. A., Mahoney, G., Quon Huber, M. S., & Zimmerman, P. (2014). PLAY project home consultation intervention program for young children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 35(8), 475–485.

Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Balla, D. A. (2005). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson.

Stadnick, N. A., Stahmer, A., & Brookman-Frazee, L. (2015). Preliminary effectiveness of project impact: A parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder delivered in a community program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 2092–2104.

Tomasello, M., & Farrar, M. J. (1986). Joint attention and early language. Child Development, 57(6), 1454–1463.

Trentacosta, C. J., Irwin, J. L., Crespo, L. M., & Beeghly, M. (2018). Financial hardship and parenting stress in families with young children with autism: Opportunities for preventive intervention. In M. Siller & L. Morgan (Eds.), Handbook of parent-implemented interventions for very young children with autism (pp. 79–91). Atlanta, GA: Springer.

Watson, L. R., Crais, E. R., Baranek, G. T., Turner-Brown, L., Sideris, J., Wakeford, L., … Nowell, S. W. (2017). Parent-mediated intervention for one-year-olds screened as at-risk for autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3520–3540

Wolf, L. C., Noh, S., Fisman, S. N., & Speechley, M. (1989). Brief report: Psychological effects of parenting stress on parents of autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 19(1), 157–166.

Zaidman-Zait, A., Mirenda, P., Duku, E., Szatmari, P., Georgiades, S., Volden, J., … Fombonne, E. (2014). Examination of bidirectional relationships between parent stress and two types of problem behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(8), 1908–1917

Zaidman-Zait, A., Mirenda, P., Duku, E., Vaillancourt, T., Smith, I. M., Szatmari, P., … Thompson, A. (2017). Impact of personal and social resources on parenting stress in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(2), 155–166

Zwaigenbaum, L., Bauman, M. L., Choueiri, R., Kasari, C., Carter, A., Granpeesheh, D., et al. (2015). Early intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder under 3 years of age: Recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics, 136(Suppl. 1), S60–S81.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board’s Autism Grants Program. This project has received IRB approval (IRB 16-81) from the University of Texas at Dallas. A version of this manuscript where presented as a Poster session presented at the American Speech and Hearing Association Convention in 2018. The authors would like to thank the children and families who participated in this study, the interventionists, and the graduate students who assisted with coding the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PRR helped to conceive of the study, led in the design of the study, supervised data collection, led in the analyses and interpretation of the data, revised the manuscript, and addressed the reviewer’s comments. SJ helped to conceive of the study, developed the parental responsivity coding, led the data reduction procedures for the parent responsivity measures and assisted with manuscript development. AJ helped to conceive of the study, performed statistical analyses and assisted with manuscript development. AF assisted with statistical analyses and participated in revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Rollins has received research grants from Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board’s Autism Grant Program and has received a speaker honorarium from Texas Autism Research and Resource Center and from the University of Louisiana, John, Jones and De Froy have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rollins, P.R., John, S., Jones, A. et al. Pathways Early ASD Intervention as a Moderator of Parenting Stress on Parenting Behaviors: A Randomized Control Trial. J Autism Dev Disord 49, 4280–4293 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04144-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04144-4