Abstract

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have higher rates of co-occurring diagnoses and use of psychotropic medication prescriptions than people with other developmental disabilities. Few studies have examined these trends in samples of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) with and without ASD. Using a random sample of 11,947 adult IDD service users from 25 states, co-occurring diagnoses and psychotropic medication use were compared for those with and without ASD. Regardless of diagnosis, individuals with ASD had higher percentages of psychotropic medication use. Controlling for co-occurring condition, age, gender, and ID level, a diagnosis of ASD predicted number of medications used. Further research is needed to understand why individuals with ASD are prescribed more medication, more often, than similarly functioning groups of individuals without ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is well established that individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) have higher rates of co-occurring psychiatric and behavioral diagnoses compared with the general population (Cooper et al. 2007; Crocker et al. 2014; Morgan et al. 2008; Tsiouris et al. 2011). Among individuals with IDD, a growing body of research suggests that people on the autism spectrum have some of the highest rates of co-occurring diagnoses (Bradley et al. 2004; Brereton et al. 2006; McCarthy et al. 2010; Morgan et al. 2003; Totsika et al. 2011) and experience greater functional impairment than those with nonspectrum disabilities (Bakken et al. 2010). Accurately identifying co-occurring diagnoses and selecting appropriate treatments is complicated by a multitude of factors. There is tremendous variation in skills and needs among individuals with IDD and individuals with IDD plus autism spectrum disorder (IDD + ASD) but also substantial overlap between symptoms of ASD, symptoms of IDD, and symptoms of other diagnoses. Furthermore, communication impairments in ASD and IDD make the assessment of feelings and thought processes, which are commonly involved in the assignment of psychiatric diagnoses, challenging.

Psychotropic medications are often prescribed for the treatment of psychiatric and behavioral symptoms (Aman et al. 2005; Deb et al. 2015; Doan et al. 2013; Holden and Gitlesen 2004; Morgan et al. 2003), and there is evidence that medication use is increasing (Aman et al. 2005; Deb et al. 2015; Esbensen et al. 2009). However, there is a distinct dearth of studies regarding psychotropic medication use in people with IDD and IDD + ASD that would inform clinical practice (Dove et al. 2012).

Co-Occurring Conditions

Prevalence estimates of co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses in individuals with IDD generally range from 30 to 50% (Einfeld et al. 2011), while estimates for ASD (with and without IDD) range from 16% (Hutton et al. 2008) to 71% (Simonoff et al. 2008) depending on methodology. Studies directly comparing cohorts of individuals with IDD and individuals with IDD + ASD generally have found higher rates of co-occurring diagnoses in individuals with IDD + ASD (Bakken et al. 2010; Bradley et al. 2004; McCarthy et al. 2010), with one exception that found lower rates (Tsakanikos et al. 2006). Comparisons between groups have been difficult to ascertain, as studies of prevalence of co-occurring diagnoses in IDD often counted ASD as a co-occurring condition. In a large-scale, population-based study that removed ASD from the calculation, prevalence of co-occurring psychiatric diagnosis in individuals with IDD dropped from 40.9 to 37.0% (Cooper et al. 2007). Studies also differed on whether challenging behaviors (e.g., aggression, self-injury) were included as a co-occurring condition along with specific diagnoses as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) systems. Cooper et al. (2007) calculated prevalence for co-occurring diagnoses excluding ASD and challenging behavior at 22.4% for individuals with IDD.

The research on adults with ASD identifies a relatively high rate of psychiatric diagnoses including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Hofvander et al. 2009; Joshi et al. 2013). Studies examining individuals with ASD have found that anxiety is one of the most commonly endorsed co-occurring diagnoses, with rates ranging from 29% (Esbensen et al. 2009) to 53% (Buck et al. 2014). A study of 62 individuals with IDD + ASD ages 14 and up found that 33.9% had an anxiety disorder compared to only 9.1% of individuals with IDD alone (Bakken et al. 2010), and a population-based study of over 1,000 individuals with IDD found that only 3.8% had an anxiety diagnosis (Cooper et al. 2007). Individuals with ASD have also been found to have higher rates of depression than those with IDD (Bakken et al. 2010; Bradley et al. 2004; Esbensen et al. 2009; Morgan et al. 2003; Smith and Matson 2010a), and this generally holds true when samples are limited to individuals with IDD + ASD (Bakken et al. 2010; Bradley et al. 2004; Morgan et al. 2003; Smith and Matson 2010a). However, one study (Buck et al. 2014) found that, compared to individuals with ASD without IDD, individuals with IDD + ASD were significantly less likely to have a formal diagnosis of anxiety or depression.

Higher rates of obsessive–compulsive disorder (Bakken et al. 2010) and bipolar disorder (Bradley et al. 2004; Morgan et al. 2003) also have been found for IDD + ASD compared to IDD alone. Results on schizophrenia and psychosis are mixed, with some finding higher prevalence among ASD (Bakken et al. 2010; Bradley et al. 2004), some finding lower (Tsakanikos et al. 2006) and others finding equal prevalence (Morgan et al. 2003).

Challenging Behavior

Challenging behaviors are typically defined as behaviors that impact the safety of the individuals and/or others or that prevent participation in community activities. The most commonly studied forms of challenging behavior are self-injury, physical aggression toward others, property destruction, stereotypes, and tantrums/disruption (Horner et al. 2002). Understanding the prevalence of challenging behaviors in developmental disabilities has been complicated by methodological issues, including differing definitions of challenging behaviors (e.g., focusing on a few specific behaviors or providing broad or vague definitions of challenging behaviors) and representativeness of samples (e.g., samples comprised of individuals living in institutional settings) (Holden and Gitlesen 2006). In individuals with IDD, estimates of the prevalence of challenging behaviors range from about 5–40% (Emerson et al. 2001; Holden and Gitlesen 2006; Kats et al. 2013). Presence of challenging behaviors increases with severity of intellectual disability (Holden and Gitlesen 2006; Kats et al. 2013; Matson and Rivet 2008; McCarthy et al. 2010) and may peak in early adulthood (Emerson et al. 2001; Holden and Gitlesen 2006). Having IDD + ASD has been associated with particularly high rates of challenging behaviors (Brereton et al. 2006; Kats et al. 2013; Smith and Matson 2010b; Totsika et al. 2011), ranging from around 40–60% (Kats et al. 2013; Matson and Rivet 2008) to as high as 87.9% (McCarthy et al. 2010). These studies also found that rates of challenging behaviors increased with severity of intellectual disability as well as severity of social impairment (Kats et al. 2013; Matson and Rivet 2008; Murphy et al. 2005). Matson and Rivet (2008) also found that adults with IDD + ASD exhibited a higher number of different challenging behaviors than adults with IDD alone. Further, specific kinds of challenging behaviors appear to be more common in individuals with IDD + ASD compared to IDD, including self-injury, stereotypies, aggression, and disruptive behavior (Kats et al. 2013; McCarthy et al. 2010; Murphy et al. 2005; Matson and Rivet 2008).

Psychotropic Medications & Number of Medications for Co-Occurring Conditions

Studies have reported between 20 and 85% of adults with IDD who live in the community are taking psychotropic medications (Deb et al. 2015; Doan et al. 2013; Holden and Gitlesen 2004; Kats et al. 2013). Among individuals with ASD, rates of medication use are similarly high, with studies reporting medication use ranging from 42 to 88% of study samples (Aman et al. 2003, 2005; Bradley et al. 2004; Buck et al. 2014; Dove et al. 2012; Esbensen et al. 2009; Kats et al. 2013; Langworthy-Lam et al. 2002; Morgan et al. 2003; Tsakanikos et al. 2006). Among individuals with IDD with and without ASD, antipsychotics, antidepressants, stimulants, and anticonvulsants are the most commonly prescribed medications (Buck et al. 2014; Deb et al. 2015; Doan et al. 2013; Esbensen et al. 2009; Langworthy-Lam et al. 2002). Few studies have compared IDD and IDD + ASD in use of medication, but two studies found that individuals with IDD + ASD were more likely to be prescribed psychotropic medications and less likely to be prescribed anticonvulsants than IDD alone (Bradley et al. 2004; Tsakanikos et al. 2006).

Evidence is lacking on the number of psychotropic medications prescribed to individuals with IDD compared to IDD + ASD. There is consensus in the literature that adults with ASD are often prescribed multiple psychotropic medications, with estimates ranging from 15% to over 50% (Buck et al. 2014; Esbensen et al. 2009; Tsakanikos et al. 2006). Presence of ID in individuals with ASD may play a role in medication use, but findings have been inconsistent and varied across medication type. For example, some studies have found no relationship between ID and medication use in individuals with ASD (Doan et al. 2013; Holden and Gitlesen 2004), while one study found increased use of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers for ASD with ID (Aman et al. 2003). Another found increased use of antipsychotics, sedatives, and anticonvulsants in individuals with ASD with ID but lower use of stimulant medication (Langworthy-Lam et al. 2002). Only one study was identified that compared number of psychotropic medications taken by IDD + ASD vs. IDD, and that study did not find statistically significant differences across these groups (Tsakanikos et al. 2006).

Several studies identified factors associated with medication use. In many cases, co-occurring diagnoses and specific problem behaviors were identified as predictors of medication use (National Core Indicators [NCI] 2011). Challenging behavior in particular is a high predictor of medication use (Doan et al. 2013; Holden and Gitlesen 2004) and often is the main concern reported by caregivers when seeking medication treatment (Sawyer et al. 2014). However, there is evidence that in a significant number of cases, medications are prescribed without being associated with a specific diagnosis or behavioral indicator. For example, two studies of adults with IDD found that approximately 30% were receiving a psychotropic medication without having a diagnosis or behavioral concern documented in their medical records (Doan et al. 2013; NCI 2011), and a study of adults with IDD + ASD found that 40% of those on a psychotropic medication did not have an additional diagnosis (Morgan et al. 2003). Indeed, several studies have found correlates of medication use that would not appear to have a direct relationship with symptomatology. Residing in a residential facility was associated with medication use in longitudinal studies of children and adults with ASD (Langworthy-Lam et al. 2002; Aman et al. 2005). Other studies have identified a trend of increasing medication use with age (Aman et al. 2003, 2005; Doan et al. 2013; Esbensen et al. 2009; Holden and Gitlesen 2004; Langworthy-Lam et al. 2002). This may be related to the increased risk for onset of seizure disorders and new psychiatric disorders during adolescence and young adulthood (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Esbensen et al. (2009) did find a trend of increased seizure disorder and other psychiatric diagnoses occurring over a 4.5-year period in their longitudinal study; however, a significant reduction in reported challenging behaviors was reported at the same time as medication use was increasing within this same sample (Shattuck et al. 2007). Several authors have suggested changes in trends in prescription practices as a possible contributor to increased medication use over time (Aman et al. 2005; Esbensen et al. 2009).

Researchers have pointed out that evidence of efficacy of medication for individuals with IDD and IDD + ASD remains lacking (Dove et al. 2012; Sawyer et al. 2014). The questionable relationship between medication use and actual symptomatology is concerning because of the possibilities of side effects that accompany these medications. The use of multiple psychotropic medications may compound this problem due to the increased potential for toxicity (National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors [NASMHPD] 2001; Spencer et al. 2013). Further, misapplication or overapplication of drugs for treatment may be preventing or discouraging the potential for effective behavioral and psychosocial interventions, which are recommended as the first line treatment of ASD (e.g., National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, United Kingdom [NICE] 2012).). In contrast, there is little to no evidence to support the use of polypharmacy to manage behaviors or treat psychiatric symptoms for ASD, IDD, or any diagnosis or condition (Mohiuddin and Ghaziuddin 2013; NASMHPD 2001).

Overall, the existing literature comparing co-occurring conditions and psychopharmacology treatment across individuals with IDD with and without ASD is limited. Few studies have compared the groups directly, and most of what is known is drawn from studies investigating these issues within samples of ASD or IDD separately. Conclusions are further limited by combining samples of children and adults despite evidence of increased medication use with age and a curvilinear relationship between age and certain kinds of medications (Aman et al. 2005; Langworthy-Lam et al. 2002) and possible regional differences or differences across countries in medication practices.

The current study utilizes a large database from a national sample of adults with IDD in 25 states (Home and Community Based Services and Intermediate Care Facilities for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities) to add to the literature on prevalence and predictors of co-occurring behavioral and psychiatric diagnosis and medication use for individuals with ASD and IDD (ASD + IDD) and IDD alone. This information may inform clinical practice by uncovering diagnostic and treatment patterns in the U.S. and comparing them to the existing research base on best practices in identification and treatment of co-occurring psychiatric and behavioral problems in ASD and IDD. Research questions included:

(1) Do adults with a co-occurring ASD diagnosis (IDD + ASD) differ from adults with IDD in type of co-occurring condition (e.g. mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, challenging behaviors, and other mental illness/psychiatric diagnosis)?

(2) Do adults with a co-occurring ASD diagnosis (IDD + ASD) differ from adults with IDD in psychotropic medication usage?

(3) What is the relationship between the number of psychotropic medications used and a co-diagnosis of ASD for adults with IDD after accounting for type and number of diagnoses?

Methods

Participants

State Selection

Twenty-five states (AL, AR, CT, FL, GA, HI, IL, IN, KY, LA, MD, MO, MS, NC, NH, NJ, NY, OH, OR, PA, SC, TX, UT, VA, and WI) voluntarily participated in the National Core Indicators (NCI) program in 2012–2013. The NCI program is a component of a national quality enhancement program designed to improve long-term supports and services for individuals with IDD. The National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disability Services (NADDDS) and the Human Services Research Institute (HRSI) run the NCI program (HSRI and NADDDS 2014).

Within State Sample Selection

Each of the 25 states was asked to collect a random sample of a minimum of 400 individuals within its population of adults (age 18+) with IDD who were receiving at least one publicly funded service other than case management. Some states placed additional restrictions on their samples (e.g., recipients of home and community-based services only). See Appendix C in NCI’s 2012–13 Adult Consumer Survey Final Report for a complete listing of each state’s specific sampling strategy (HSRI and NADDDS 2014).

Overall, participating states had sample sizes ranging from 326 (IL) to 1447 (PA) with an average of 508. The total sample consisted of 12,706 individuals with IDD who received at least one service other than case management. However, 759 (6.0%) participants did not answer the item regarding an ASD diagnosis, and 608 (4.8%) reported no ID leaving an overall sample of 11,339.

Analytic Sample

Of the 11,339, participants ranged in age from 18 to 96 years with the average age of 42.7 years (SE = 0.5). Just under half (42.4%) were female. Almost three-quarters (72.7%) were white, 20.2% black or African American, and 5.8% were another race, and 1.3% selected two or more races. Under 5.0% of individuals were from Hispanic backgrounds. With respect to ID level, 13.2% had profound ID, 16.4% had severe ID, 31.9% had moderate ID, and 38.5% had mild ID. Three-quarters of the individuals were independently mobile and used spoken language (76.2 and 75.1%, respectively), and 45.1% had a guardian. For living arrangement, 36.9% of individuals lived in a family owned home while an additional 30.1% lived in a group home with 1–15 residents. Others lived in their own home (13.5%), in foster care or a host home (6.8%), in an agency operated apartment setting (4.9%), in an institutional setting with 16 or more individuals with IDD (4.7%), in a setting type not listed (2.7%), and in a nursing home (0.6%). An ASD diagnosis was present for 1265 (112%) of the individuals.

Instrument

The NCI Adult Consumer Survey (NCI-ACS) 2012–2013 was administered to individuals with a developmental disability who received at least one service, other than case management. The survey has three components. The first component is the “Background Section,” which contains information related to the individual’s demographic characteristics, health issues, diagnoses, verbal level and level of mobility, use of services, behavioral support needs, and daily activities and employment. Items in this section used to determine ASD status included a set of items documenting presence and level of ID and presence of “other disabilities or conditions” noted in the individual’s record. The individual was included in the ASD group if the response option “Autism Spectrum Disorder (e.g., Autism, Asperger Syndrome, Pervasive Developmental Disorder)” was checked. These data come mainly from the individual’s records as well as from case managers and/or setting administrators. State database records are also used, if necessary, to obtain exam and health history and employment status. The second component, “Section I,” focuses on personal experiences regarding home and employment/daily activities environments, relationships with friends and family members, satisfaction with his/her supports and services, and self-directed supports. This information comes directly from interviewing the individual receiving services. The third component, “Section II” concentrates on the individual’s rights, access to services, community involvement, and choice. These questions are objective and answered by the individual receiving services or a proxy (HSRI and NADDDS 2014).

The NCI-ACS is delivered via an in-person, face-to-face interview with the intent of gathering data directly from the individual. States typically hire state staff, advocacy organizations, or private contractors for survey administration. The individual’s staff members, a personal case manager, relatives, his/her service provider, or other close contacts cannot administer the survey. Training is provided for those administering survey as well as to those doing data entry into the Online Data Entry Survey Application (ODESA). Training includes manuals and videos, a review of the survey instrument, presentation slides, scripts for scheduling interviews, picture response formats, and a list of frequently asked questions (HSRI and NADDDS 2014).

Variables

Covariates

Age was a single item ranging from 18 to 96 years with an average of 42.68 years (SE = 0.53).

Gender was a single item with male (coded 0) and female (coded 1) categories.

Race was a single item that had six options including American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese or Other Asian), Black or African American, Pacific Islander (Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, or Other Pacific Islander), White, or Other Race Not Listed. Due to low numbers in some race categories, this variable was dummy coded for analyses into the following three groups: White, Black/African American, and Other. White was the referent group.

Level of ID was measured by a single item with five levels including mild, moderate, severe and profound. For the linear regression models, it was considered quasi-continuous with a higher score indicating a more severe level of ID.

Co-Occurring Condition Variables

A single item asked what other disabilities or conditions were noted in the individual’s record. Respondents were allowed to check all that applied. Each of the co-occurring conditions was dichotomous with a code of 1 representing ‘yes’ and a 0 representing ‘no’. The following options were included in the NCI survey:

Mood Disorder was defined as depression, mania, bipolar disorder, etc.

Anxiety Disorder was defined as obsessive disorders, panic disorders, etc.

Psychotic Disorder was defined as schizophrenia, hallucinations, etc.

Other Mental Illness/Psychiatric Diagnosis was an option with no specific definition or examples provided.

Challenging behavior was defined as aggression, self-injurious behavior, etc.

Chemical Dependency was an option with no specific definition.

Total Co-Occurring Conditions was created by counting how many of the five co-occurring conditions (mood disorder, anxiety disorder, psychotic disorder, behavior challenges, and other mental illness/psychiatric diagnosis) the participant endorsed. The average number of co-occurring conditions was 0.69 (SE = 0.04) with a range of 0–5. A dichotomous version of this was also created indicating presence or absence of any co-occurring diagnosis.

Psychotropic Medication Variables

Four items asked what medications the individual was currently taking to treat mood disorders, anxiety, behavior challenges and psychotic disorders. Each of the medication types was dichotomous with a code of 1 representing ‘yes’ and a 0 representing ‘no’. Information on medications was recommended to be gathered through referencing agency records and from an agency staff member, such as a case manager/service coordinator, and family if necessary; medication names and dosages were not collected as part of the NCI survey.

Mood Disorder Medication was defined as any drug prescribed to stabilize or elevate mood as with treating depression, mania, or bipolar disorder.

Anxiety Disorder Medication was defined as any drug prescribed to reduce anxiety symptoms or treat anxiety disorders like obsessive and panic disorders.

Psychotic Disorder Medication was defined as any drug prescribed to treat psychotic disorders like schizophrenia or psychotic symptoms. Examples included anti-psychotics or neuroleptics medications.

Challenging Behavior Medication was defined as any drug prescribed to modify behavior such as ADHD, aggression, and self-injurious actions. Examples included stimulants, beta-blockers, and sedatives.

Total Psychotropic Medications was created by tallying the number of psychotropic medications (mood, anxiety, psychotic and behavior) taken by participants. The average number of psychotropic medications taken was 1.05 (SE = 0.04) with a range of 0 to 4 for the full sample. A dichotomous version of this was also created indicating the presence of any drug use.

Analysis

Analyses were run in STATA version 13 (StataCorp 2013a) using “svy” commands to address sampling participants within state as state was the primary sampling unit. This process controls for the potential effect of state differences, such as sampling bias and policy differences, that could affect diagnoses and psychotropic medication use. Analyses were evaluated using the alpha level (α = 0.05).

Missing data analyses were conducted to compare those who were excluded from the sample (e.g., did not respond to the item regarding autism diagnosis or had no ID, n = 1367) with those who answered the autism diagnosis item (n = 11,339). Those included in the sample had higher percentages a higher percentage of males (p = 0.045), of ID (p < 0.001), were older (p < 0.001), had a lower percentage of individuals in own and parent/family homes and a higher percentage of individuals in group homes and institutions (p < 0.001), had higher percentages of mood (p = 0.032), behavior (p < 0.001), and psychotic issues (p = 0.023), and had higher percentages for taking mood (p < 0.001), anxiety (p = 0.001), challenging behavior (p < 0.001), and psychotic disorder (p < 0.001) medications. There were no differences in race (p = 0.395) ethnicity (p = 0.129), or anxiety issues (p = 0.165).

Analysis followed a structured logic that followed involved three phases: (a) descriptive exploration of our sample in order to examine whom our sample represented demographically; (b) comparisons between individuals with and without ASD in terms of co-occurring psychological conditions and use of medications to treat those conditions in order to establish if such differences exist to support our final analysis; and (c) modeling of the number of psychotropic medication used, controlling for other characteristics, to highlight the potential a co-occurring ASD and IDD diagnosis can have on the use of multiple psychotropic medications.

Frequency distributions were used to generate descriptive statistics. To examine relationships of co-occurring conditions and psychotropic medication use between those with and without an ASD diagnosis, cross-tabulation tables with Chi-Square tests (χ2) were run. The second-order correction of Rao and Scott (1984) is used by STATA’s “svy” commands to correct the Pearson χ2 for the survey design and convert it into an F statistic. P-values from the corrected F statistic are interpreted in the same manner as p-values for a Pearson χ2 statistic. A t-test was run to compare those with and without ASD on the continuous variables, total number of co-occurring conditions and total number of psychotropic medications taken. Since there is no t-test command in STATA, the “means” command followed by the Adjusted Wald test provided an F statistic. Taking the square root of the F statistic produces a t-value (StataCorp 2013b). Lastly, a linear regression was run to examine the relationships between ASD diagnosis and number of psychotropic medications taken after adjusting for co-occurring conditions and demographic variables.

Results

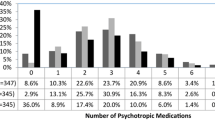

Of the 11,339 study participants, 2504 (22.9%) had mood disorders, 1563 (14.3%) had anxiety disorders, 1737 (15.9%) had behavior challenges, 1077 (9.8%) had psychotic disorders, 665 (6.1%) had other mental illness or psychotic diagnoses, and 28 (0.2%) had chemical dependency issues. Overall, 5927 (54.2%) of the sample had no co-occurring conditions. However, 3235 (29.6%) had one co-occurring condition, 1209 (11.1%) had two co-occurring conditions, 423 (3.9%) had 3 co-occurring conditions, 126 (1.2%) had four co-occurring conditions. A small number, 24 (0.2%), of the sample had all five co-occurring condition diagnoses.

For psychotropic medications, 3982 (37.0%) were taking mood disorder medications, 3079 (28.9%) were taking medications for anxiety disorders, 1846 (17.4%) were taking psychotic disorder medications, and 2785 (26.0%) were taking medications for challenging behavior. Individuals could be taking more than one kind of medication. Of the total sample, over half (53.5%) were taking at least one psychotropic medication. Specifically, 2458 (22.1) were taking one medication, 1808 (16.3%) were taking two medications, 1102 (9.9%) were taking three medications, and 578 (5.2%) were taking all four types of medications asked about.

Comparisons between participants with and without ASD were examined on co-occurring conditions and use of psychotropic medications. Chemical dependency was also not included as only 28 individuals from the entire sample endorsed it. There were 1265 (11.2%) sample members with a diagnosis of ASD and 10,074 (88.8%) without this diagnosis.

Co-Occurring Conditions for Individuals With and Without ASD

As shown in Table 1, the percentage of individuals with mood disorders was significantly lower for individuals with ASD (18.2%) than those without ASD (23.5%), F (1, 24) = 5.03, N = 10,942, p = 0.035. A similar trend was seen with psychotic disorders. Those with ASD had a nearly significant lower percentage of diagnosed psychotic disorders (8.2%) than those without an ASD diagnosis (10.1%), F (1, 24) = 4.24, N = 10,943, p = 0.051. However, the opposite was found with respect to both anxiety disorders and challenging behavior diagnoses. The percentage of individuals with anxiety disorders was significantly higher for individuals with ASD (19.5%) than those without ASD (13.6%), F (1, 24) = 16.49, N = 10,943, p = 0.001. And, those with ASD had a significantly higher percentage of diagnosed challenging behavior (25.3%) than those without an ASD diagnosis (14.7%), F (1, 24) = 46.49, N = 10,942, p < 0.001. No differences were seen for other mental illness/psychiatric diagnoses, F (1, 24) = 0.15, N = 10,942, p = 0.702. About 6.0% of both groups had other mental illness/psychiatric diagnoses. There was also no significant difference between groups with the presence of at least one co-occurring diagnosis, F (1, 24) = 0.03, N = 10,944, p = 0.862.

With respect to the number of diagnoses, there were significant differences between those with and without ASD, F (1, 24) = 4.81, N = 10,944, p = 0.038. Those with ASD had, on average, 0.78 diagnoses (SE = 0.06), and those without averaged 0.68 (SE = 0.04) diagnoses.

Psychotropic Medication Use for Individuals With and Without ASD

As shown in Table 2, the percentage of individuals taking all forms of psychotropic medications was significantly higher for those with ASD. Specifically, for mood disorder medications, individuals with IDD + ASD had a significantly higher percentage of this medication use (41.8%) compared to those without ASD (36.4%), F (1, 24) = 11.06, N = 10,778, p = 0.003. A similar trend was seen with medications for psychotic disorder. Those with ASD had a significantly higher percentage of using psychotic disorder medications (20.0%) than those without an ASD diagnosis (17.1%), F (1, 24) = 6.03, N = 10,625, p = 0.022. The discrepancy between those with and without ASD and anxiety disorder medications was much greater than with mood and psychotic medications. The percentage of individuals taking anxiety disorder medication was significantly higher for individuals with IDD + ASD (43.0%) than those without ASD (27.2%), F (1, 24) = 81.9, N = 10,652, p < 0.001. Those with ASD had one and one-half times the percentage of individuals taking medications for challenging behavior (47.3%) than those without an ASD diagnosis (23.3%), F (1, 24) = 236.29, N = 10,716, p < 0.001. There were significant differences when looking at those who took no medications and those who took at least one, F (1, 24) = 65.57, N = 11,111, p < 0.001; 68.8% of those with an ASD diagnosis were taking one or more medications while only 51.6% of those without an ASD took at least one. When looking at the total number of psychotropic medications taken, those with an ASD diagnosis took significantly more, F (1, 24) = 102.12, N = 11, 111, p < 0.001. Those with IDD + ASD took, on average, 1.45 (SE = 0.06) psychotropic medications relative to those without ASD (M = 1.00, SE = 0.04).

Linear Regression Analyses

While the bivariate findings on co-occurring conditions and types of psychotropic medications taken by ASD status reported in Tables 1 and 2 are interesting, they remain ambiguous because of important differences between sample members with and without ASD on characteristics such as type and number of diagnoses. That said, it is also important to factor in demographic variables including ID level, age, race, and gender.

As found in Hewitt et al. (2017), there were significant differences between those with and without ASD with respect to ID level. There was a higher percentage of those with severe ID among the ASD sample (25.2% vs. 15.4%) and a lower percentage of those with mild ID among those without ASD (29.2% vs. 39.6%). There were also significant age and gender differences between individuals with and without an ASD diagnosis. Individuals with a diagnosis of ASD were significantly younger (M = 33.19, SE = 0.69 vs. M = 43.56, SE = 0.52) and male (76.6% vs. 55.3%). Previous work has demonstrated that African American children may be prescribed medication less often than white children (Frazier et al. 2011). However, there were no significant differences by race in our analyses.

To examine the relationship of ASD status with number of psychotropic medications taken, adjusting for important participant characteristics and type of diagnosis, two linear regression analyses were conducted. Number of co-occurring conditions was omitted from the analysis due to collinearity issues. The first model included all covariates (available upon request)but excluded the ASD diagnosis. This model was run to establish the proportion of variance explained without an ASD diagnosis (42.9%). Next, we ran our full model including the ASD diagnosis. The results of the full model are summarized in the Table 3.

Overall, together these variables predict the number of psychotropic medications taken, F (11, 14) = 301.76, N = 9546, p < 0.001. With type of co-occurring condition, age, gender, race, and level of ID taken into account statistically, individuals with ASD were more likely to be taking more psychotropic medications than those without ASD (p < 0.001). Those who had mood (p < 0.001), anxiety (p < 0.001), and psychotic (p < 0.001) diagnoses, behavior challenges (p < 0.001), or other mental illness/psychiatric diagnoses (p < 0.001), were younger (p = 0.017), or were male (p = 0.004) were more likely to take a greater number of psychotropic medications. There was no significant relationship between level of ID or race and the number of psychotropic medications taken. Overall, these variables accounted for 43.8% of the variance in the number of psychotropic medications taken, compared to the baseline model, which accounted for 42.9% of the variance in number of psychotropic medications taken. This comparison indicates that the addition of ASD diagnosis explains an additional 1.0% of the variance in number of psychotropic medications taken.

Discussion

The current study utilized a large, national sample of adult users of intellectual and developmental disability (IDD/DD) services to examine use of psychotropic medication in adults with developmental disorders. The study was unique in its focus on adults with intellectual disability and its ability to compare adults with IDD with and without ASD. Previous studies of medication use among these populations were limited in that ASD groups often included people with a range of intellectual abilities, which clouded understanding the relationship between ASD, IDD, and diagnostic and medication treatment practices.

Similar to previous research (Bakken et al. 2010; Bradley et al. 2004; McCarthy et al. 2010), the results of the current study reveal that individuals with an ASD diagnosis had higher percentages of anxiety disorders and challenging behavior diagnoses, and a higher number of co-occurring diagnoses overall, compared to individuals with IDD alone. However, the study diverged from previous studies in its finding of lower percentages of mood disorders in individuals with ASD diagnoses compared to IDD alone. Groups did not differ in percentages diagnosed with psychotic and other disorders. Yet, the discrepancy in medication use between IDD + ASD and IDD groups was greater than expected given the prevalence of co-occurring conditions within the two groups. For example, the prevalence of challenging behaviors was 63% higher in individuals with IDD + ASD compared to IDD alone, but use of medication for challenging behavior was 100% higher (twice the rate) in individuals with IDD + ASD. Individuals with ASD were prescribed medication for mood disorder more often than individuals with IDD alone even though the co-occurrence of mood disorder diagnoses was lower in individuals with IDD + ASD compared to IDD. Overall, almost 50% more individuals with IDD + ASD took psychotropic medications than individuals with IDD alone, even though there was no difference in the number of individuals diagnosed with a co-occurring condition of any kind (45% vs. 44%).

The findings support previous research that individuals with ASD diagnoses were using a greater number of psychotropic medications compared to IDD alone. This was the case for all classes of medication, despite the finding that IDD + ASD and IDD groups did not differ on co-occurring psychotic disorders, and individuals with an ASD diagnosis had lower percentages of co-occurring mood disorders. Having a diagnosis of ASD remained a significant predictor of medication use after controlling for demographic variables and level of ID. Characteristics inherent to ASD may have influenced this relationship. Individuals with ASD have been found to have greater functional impairment overall (Bakken et al. 2010) and to engage in different, more varieties of, and more severe challenging behaviors than individuals with IDD alone (McCarthy et al. 2010; Murphy et al. 2005; Matson and Rivet 2008). The use of multiple psychotropic medications has been associated with the management of socially disruptive behaviors, for example (Stolker et al. 2001). Although significant, it appears this may be a small effect (a 1% change in medication use). This finding is confounded by the strong relationship between diagnosis and medication use overall. However, given the potential long-term impact psychotropic medication use, especially the use of more than one medication, can have, this small effect can have a large impact when multiplied across the nation.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Information was taken from survey data and thus, information on why medications were prescribed and what behaviors or conditions they were intended to target was not available. This is important, as different classes of medications can be used to treat a variety of co-occurring conditions. For example, individuals with ASD diagnoses had lower percentages of co-occurring mood disorder diagnoses but were prescribed medications for mood disorders in greater numbers than individuals with IDD alone. This may reflect a tendency to prescribe selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat symptoms of anxiety or challenging behaviors in individuals with ASD, which were diagnosed in greater numbers in the ASD. The research literature is mixed with some studies reporting improvements from SSRIs in behaviors such as reduced repetitive behaviors, obsessions, self-injury, aggression, perseverative behaviors, anxiety, and irritability (Aman et al. 2003, 2005; Posey et al. 2006). Thus, results of this study cannot shed light on whether medications are being wrongly applied to particular conditions in individuals with ASD; it only indicates that certain medications are being used more often in individuals with ASD diagnoses compared to similar individuals without ASD diagnoses.

The current study did not include metrics of severity of symptoms of co-occurring diagnoses or of challenging behaviors, and this information is likely very important in the decision-making process of prescribing medication. Previous studies have found that severity of challenging behaviors increases with the presence of ASD and with severity of intellectual disability (Kats et al. 2013; Matson and Rivet 2008; Murphy et al. 2005). In this study, a greater proportion of individuals with ASD had ID levels in the severe-profound range, but level of ID was not a significant predictor of psychotropic medication use. However, given the research on greater severity of co-occurring conditions in ASD, symptom severity may have led to increased use of medication in the current sample.

This study examined results for the NCI sample as a whole. It did not examine regional differences or differences at the state level. However, a process was used to control for these differences, described in our methods section. Regional differences in co-occurring diagnostic patterns and use of psychotropic medication may reflect policy and prescriber practices that would be important to understand in studying trends in use of medication. An avenue for future research would be to study these trends at the state level to further investigate potential influences of prescriber practices.

The variables on medication use in the NCI also presented limitations. The variables came from individual survey items phrased “Does this person currently take medications to treat: (a) mood disorders, (b) anxiety, (c) behavior challenges, and (d) psychotic disorders.” No specific medications were provided as examples of what medications were included in each of the categories, and items were not phrased in terms of medication classes (e.g., benzodiazepines vs. beta blockers), which would have aided in our analyses. Information on specific medications and dosages was not collected to understand if medications used to treat different conditions (e.g., anxiety) were from the class of medication corresponding with those conditions (e.g., benzodiazepines). However, results indicated higher medication use overall for the ASD group regardless of medication class. Finally, the number of each type of medication taken was not asked. It was also not possible to determine if the individual had more than one diagnosis within each of the categories. It is possible that some participants had more than one medication or diagnosis within a medication category; therefore, comorbidity and/or polypharmacy may be underestimated.

In its use of survey methodology, the NCI program requires a standardized approach that does not allow for in depth, individualized exploration of the issues examined in the NCI survey nor of the decision-making process used by respondents when responding. As with all diagnoses captured on the NCI tool, the presence of a diagnosis of ASD on the survey instrument depends on whether the respondent finds a record of such diagnosis in the person’s administrative records. Some people (particularly older sample members) may have characteristics of ASD and yet never have been given an ASD diagnosis; however, age was controlled in our regression analyses. Finally, states participate on a voluntary basis, so they are not randomly selected into the study.

The focus of this study was specifically on co-occurring behavioral and psychiatric diagnosis and medication use for individuals with ASD + IDD compared to IDD alone, as individuals with ASD and significant IDD has been a particularly understudied subgroup (Siegel 2018), and results have been mixed as to the relationship between co-occurring ID and medication use in ASD (Aman et al. 2003; Doan et al. 2013; Holden and Gitlesen 2004; Langworthy-Lam et al. 2002). As such, results may not generalize to the ASD population without ID. However, results add to the literature on current treatment trends in individuals on the severe end of the autism spectrum.

Implications

Results highlight that adults with ASD and IDD continue to experience high levels of co-occurring diagnoses, and particularly for those with ASD diagnoses, psychotropic medication continues to be a frequently used treatment. Individuals with ASD continue to stand out as being prescribed medication more frequently, and receiving a greater number of medications overall, than other individuals without ASD. The current study built upon this finding by showing that this relationship held true in a sample of individuals with similar levels of intellectual impairment (i.e., individuals receiving IDD/ID services). Even after controlling for co-occurring diagnoses, having ASD predicted not just whether psychotropic medications were used but also the use of multiple medications.

Future research is needed to understand specific factors involved in having a diagnosis of ASD that leads to greater use of medication as a treatment. Findings have important implications for both public policy and service delivery for adults with ASD. The prevalence of both co-occurring diagnoses and medications has important implications for the health and social service systems that provide services and supports for individuals with ASD and their families.

Future studies should more systematically explore co-occurring diagnosis and medication use based on challenging behavior diagnosis and the presence or absence of behavioral support programs. It may be that these results vary greatly based on the availability and enrollment in such support programs.

Understanding the outcomes for adults with ASD (including use of psychotropic medications) is important for planning and developing supports and services and promoting quality of life for individuals with ASD and families. The increased rates of psychotropic medication use for adults with ASD highlights the need for increased education for both individuals with ASD and their families around medication use, safety, and signs and symptoms of medication side effects. That medication use continues to be high in these populations also points to the need to study the influence of psychotropic medications on the health, challenging behaviors, and symptoms of ASD and co-occurring diagnoses over time. Future research is needed to explore the impact of co-occurring psychiatric disorders as well as both the safety and efficacy of psychotropic medications for adults with ASD.

References

Aman, M. G., Lam, K. S., & Collier-Crespin, A. (2003). Prevalence and patterns of use of psychoactive medicines among individuals with autism in the Autism Society of Ohio. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(5), 527–534.

Aman, M. G., Lam, K. S., & Van Bourgondien, M. E. (2005). Medication patterns in patients with autism: Temporal, regional, and demographic influences. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 15(1), 116–126.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Philadelphia: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Bakken, T. L., Helverschou, S. B., Eilertsen, D. E., Heggelund, T., Myrbakk, E., & Martinsen, H. (2010). Psychiatric disorders in adolescents and adults with autism and intellectual disability: A representative study in one county in Norway. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(6), 1669–1677.

Bradley, E. A., Summers, J. A., Wood, H. L., & Bryson, S. E. (2004). Comparing rates of psychiatric and behavior disorders in adolescents and young adults with severe intellectual disability with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), 151–161.

Brereton, A. V., Tonge, B. J., & Einfeld, S. L. (2006). Psychopathology in children and adolescents with autism compared to young people with intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(7), 863–870.

Buck, T. R., Viskochil, J., Farley, M., Coon, H., McMahon, W. M., Morgan, J., & Bilder, D. A. (2014). Psychiatric comorbidity and medication use in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3063–3071.

Cooper, S. A., Smiley, E., Morrison, J., Williamson, A., & Allan, L. (2007). Mental ill-health in adults with intellectual disabilities: Prevalence and associated factors. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(1), 27–35.

Crocker, A. G., Prokić, A., Morin, D., & Reyes, A. (2014). Intellectual disability and co-occurring mental health and physical disorders in aggressive behaviour. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(11), 1032–1044.

Deb, S., Unwin, G., & Deb, T. (2015). Characteristics and the trajectory of psychotropic medication use in general and antipsychotics in particular among adults with an intellectual disability who exhibit aggressive behaviour. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59(1), 11–25.

Doan, T. N., Lennox, N. G., Taylor-Gomez, M., & Ware, R. S. (2013). Medication use among Australian adults with intellectual disability in primary healthcare settings: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 38(2), 177–181.

Dove, D., Warren, Z., McPheeters, M. L., Taylor, J. L., Sathe, N. A., & Veenstra-VanderWeele, J. (2012). Medications for adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Pediatrics, peds-2012.

Einfeld, S. L., Ellis, L. A., & Emerson, E. (2011). Comorbidity of intellectual disability and mental disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 36(2), 137–143.

Emerson, E., Kiernan, C., Alborz, A., Reeves, D., Mason, H., Swarbrick, R., … Hatton, C. (2001). The prevalence of challenging behaviors: A total population study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22(1), 77–93.

Esbensen, A. J., Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M. M., & Aman, M. G. (2009). A longitudinal investigation of psychotropic and non-psychotropic medication use among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(9), 1339–1349.

Frazier, T. W., Shattuck, P. T., Narendorf, S. C., Cooper, B. P., Wagner, M., & Spitznagel, E. L. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of psychotropic medication use in adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder with and without caregiver-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 21(6), 571–579.

Hewitt, A. S., Stancliffe, R., Hall-Lande, J., Nord, D., Pettingell, S., Hamre, K., & Hallas-Muchow, E. (2017). Characteristics of adults with autism spectrum disorder who use residential services and supports through adult developmental disabilities in the United States. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 34, 1–9.

Hofvander, B., Delorme, R., Chaste, P., Nydén, A., Wentz, E., Ståhlberg, O., … Råstam, M. (2009). Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 9(1), 35.

Holden, B., & Gitlesen, J. P. (2004). Psychotropic medication in adults with mental retardation: Prevalence, and prescription practices. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25(6), 509–521.

Holden, B., & Gitlesen, J. P. (2006). A total population study of challenging behaviour in the county of Hedmark, Norway: Prevalence, and risk markers. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27(4), 456–465.

Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Strain, P. S., Todd, A. W., & Reed, H. K. (2002). Problem behavior interventions for young children with autism: A research synthesis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(5), 423–446.

HSRI and NADDDS. (2014). 2012–2013 ACS Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.nationalcoreindicators.org/upload/core-indicators/FINAL2012- 13_ACS_Final_Report_2.pdf.

Hutton, J., Goode, S., Murphy, M., Le Couteur, A., & Rutter, M. (2008). New-onset psychiatric disorders in individuals with autism. Autism, 12(4), 373–390.

Joshi, G., Biederman, J., Petty, C., Goldin, R. L., Furtak, S. L., & Wozniak, J. (2013). Examining the comorbidity of bipolar disorder and autism spectrum disorders: A large controlled analysis of phenotypic and familial correlates in a referred population of youth with bipolar I disorder with and without autism spectrum disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6), 578–586.

Kats, D., Payne, L., Parlier, M., & Piven, J. (2013). Prevalence of selected clinical problems in older adults with autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 5(1), 27.

Langworthy-Lam, K. S., Aman, M. G., & Van Bourgondien, M. E. (2002). Prevalence and patterns of use of psychoactive medicines in individuals with autism in the Autism Society of North Carolina. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 12(4), 311–321.

Matson, J. L., & Rivet, T. T. (2008). Characteristics of challenging behaviours in adults with autistic disorder, PDD-NOS, and intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 33(4), 323–329.

McCarthy, J., Hemmings, C., Kravariti, E., Dworzynski, K., Holt, G., Bouras, N., & Tsakanikos, E. (2010). Challenging behavior and co-morbid psychopathology in adults with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(2), 362–366.

Mohiuddin, S., & Ghaziuddin, M. (2013). Psychopharmacology of autism spectrum disorders: A selective review. Autism, 17(6), 645–654.

Morgan, C. N., Roy, M., & Chance, P. (2003). Psychiatric comorbidity and medication use in autism: A community survey. The Psychiatrist, 27(10), 378–381.

Morgan, V. A., Leonard, H., Bourke, J., & Jablensky, A. (2008). Intellectual disability co-occurring with schizophrenia and other psychiatric illness: population-based study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193(5), 364–372.

Murphy, G. H., Beadle-Brown, J., Wing, L., Gould, J., Shah, A., & Holmes, N. (2005). Chronicity of challenging behaviours in people with severe intellectual disabilities and/or autism: A total population sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(4), 405–418

National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, Medical Directors Council and State Medicaid Directors (2001). NASMHPD Medical Directors’ Technical Report on Psychiatric Polypharmacy. Alexandria, VA.

National Core Indicators (NCI). (2011). What does NCI tell us about people with dual diagnosis? NCI Data Brief, 2, 1–8. Retrieved from https://www.nationalcoreindicators.org/upload/core-indicators/Data_Brief_--_dual_dx_--_Issue_2_--_April_4_2011_1.pdf.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, UK [NICE]. (2012). Autism: Recognition, referral, diagnosis and management of adults on the autism spectrum. Clinical Guideline, 142, 18–19 http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg142.

Posey, D. J., Erickson, C. A., Stigler, K. A., & McDougle, C. J. (2006). The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in autism and related disorders. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 16(1–2), 181–186.

Rao, J. N. K., & Scott, A. J. (1984). On chi-squared tests for multiway contingency tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. Annals of Statistics, 12, 46–60.

Sawyer, A., Lake, J. K., Lunsky, Y., Liu, S. K., & Desarkar, P. (2014). Psychopharmacological treatment of challenging behaviours in adults with autism and intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(7), 803–813.

Shattuck, P. T., Seltzer, M. M., Greenberg, J. S., Orsmond, G. I., Bolt, D., Kring, S., & Lord, C. (2007). Change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors in adolescents and adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(9), 1735–1747.

Siegel, M. (2018). The severe end of the spectrum: Insights and opportunities from the autism inpatient collection (AIC). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 3641–3646.

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929.

Smith, K. R., & Matson, J. L. (2010a). Psychopathology: Differences among adults with intellectually disabled, comorbid autism spectrum disorders and epilepsy. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(3), 743–749.

Smith, K. R., & Matson, J. L. (2010b). Behavior problems: Differences among intellectually disabled adults with co-morbid autism spectrum disorders and epilepsy. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(5), 1062–1069.

Spencer, D., Marshall, J., Post, B., Kulakodlu, M., Newschaffer, C., Dennen, T., … Jain, A. (2013). Psychotropic medication use and polypharmacy in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 132(5), 833–840.

StataCorp. (2013a). Stata Statistical Software: Release 2013. College Station: StataCorp LP.

StataCorp. (2013b). Stata survey data reference manual: Release 13. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Stolker, J. J., Heerdink, E. R., Leufkens, H. G., Clerkx, M. G., & Nolen, W. A. (2001). Determinants of multiple psychotropic drug use in patients with mild intellectual disabilities or borderline intellectual functioning and psychiatric or behavioral disorders. General Hospital Psychiatry, 23(6), 345–349.

Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Emerson, E., Lancaster, G. A., & Berridge, D. M. (2011). A population-based investigation of behavioural and emotional problems and maternal mental health: Associations with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(1), 91–99.

Tsakanikos, E., Costello, H., Holt, G., Bouras, N., Sturmey, P., & Newton, T. (2006). Psychopathology in adults with autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(8), 1123–1129.

Tsiouris, J. A., Kim, S. Y., Brown, W. T., & Cohen, I. L. (2011). Association of aggressive behaviours with psychiatric disorders, age, sex and degree of intellectual disability: a large-scale survey. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(7), 636–649.

Funding

This publication is supported by Grant #90RT5019-01-01 at the Research and Training Center for Community Living from the National Institute on Disability Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Grant # 90IF0101-03-00, United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Administration on Community Living, Administration on IDD; and the University of Minnesota Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disabilities (MNLEND) Program, U.S. Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), Grant 5 T73MC12835-09-00. Grantees undertaking projects under government sponsorship are encouraged to express freely their findings and conclusions. Points of view or opinions do not therefore necessarily represent official NIDILRR, USDHHS, or MCHB policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AE participated in study design and interpretation and drafted the manuscript; AH conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript; JHL participated in interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript; SLP participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript; and JH contributed to interpretation and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Amy Esler declares that she has no conflict of interest. Amy Hewitt declares that she has no conflict of interest. Jennifer Hall-Lande declares that she has no conflict of interest. Sandra L. Pettingell declares that she has no conflict of interest. James Houseworth declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Esler, A., Hewitt, A., Hall-Lande, J. et al. Psychotropic Medication Use for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder who Receive Services and Supports Through Adult Developmental Disability Services in the United States. J Autism Dev Disord 49, 2291–2303 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03903-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03903-7